Battle of Drewry's Bluff

by Dan Welch

McClellan’s slowness in launching the Peninsula Campaign, which began with the departure of the Federal fleet on March 17, 1862, allowed Confederate forces around Richmond valuable time to construct defenses on land and on water. As McClellan’s army prepared to board their boats in Alexandria, Major Augustus Harrison Drewry, Company C, 2nd Regiment Virginia Artillery, sought permission to build a fort on his personal property in which his unit could deploy and in effect add yet another layer to Richmond’s defense in depth. Augustus inherited the tract of land just eight miles south of Richmond by river from his second wife Mary A. Harrison. The tract included a high bluff, over 100 feet high above the water, that was adjacent to the James River. Additionally, although the approach to the fort from the southeast and Hampton Roads consisted of a mile of straight waterway, at the bluff, there was a bend in the James River that provided any cannon on the bluff plunging fire on ships coming from that direction. A complement of guns placed here, however, could command that mile-long, straight section of the river below the bend. Furthermore, impediments and obstructions could be dropped into the river’s channel, further narrowing the physical area that Federal gunboats could utilize due to their drafts. Eventually, these obstacles would include sunken cribs filled with stones, pilings, and even the hulks of several sunken river-faring vessels. These efforts would slow the rate of speed at which Federal ships could safely move, thus allowing more time for the Confederate artillery to fire upon them. Drewry took his company to the site on the bluff where Fort Darling would be built on March 17. They began working on fortifications and emplacing guns. Initially there was little enthusiasm or support from the government and military authorities in Richmond. But by mid April work on the fortifications accelerated, blocking the river and training the soldiers to serve the guns also advanced. With the threat of McClellan advancing up the James River both Robert E. Lee and Naval Secretary Stephen Mallory turned their full attention to strengthening Fort Darling including sending Confederate marines to defend against an attack by landed infantry and placing guns on Chaffin’s Bluff about a mile downriver from Drewry’s Bluff. Work continued right up to the moment on May 15 that the Federal flotilla of two ironclads and 3 wooden gunships engaged the Confederates at Drewry’s Bluff at 7:45 a.m. The two ironclads USS Galena and USS Monitor took up positions near the bluff and the three wooden gunboats, USS Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck anchored at a further distance and opened fire which was returned by the Confederate batteries. As the battle wore on casualties on both sides mounted. The battle lasted nearly four hours. At 11:05 a.m. the badly damaged wooden gunboats turned and started to steam away from Fort Darling. Both the Galena and Monitor were damaged and suffered casualties, the former more than the latter. Both ironclads followed the wooden gunboats in retreat. Following the battle, three Medals of Honor were awarded to federal sailors. The last-minute push to complete the works at Drewry’s Bluff and rush reinforcements of men and guns to the position no doubt greatly contributed to the Confederate victory on May 15, 1862. In all twelve Confederate guns were emplaced and were engaged at Drewry’s Bluff 1,800 soldiers and marines were stationed at Chaffin’s Bluff and Drewry’s Bluff and 4,000 Confederate reinforcements were marching towards the Fort when the battle started. In William I. Clopton, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 34, (January-December 1906) the author stated, “A glorious victory over the hitherto invincible navy of the United States was achieved and the fall of Richmond was prevented, for if the Federal gunboats had succeeded in passing Drewry’s Bluff on that day the capital of the Confederacy would have at once been at their mercy, and the Confederate troops would have been compelled to retreat from Richmond, and probably from Virginia.” A post war poem by Sergeant Samuel Mann who fought with the Confederates at Fort Darling summed up the victory best: The Monitor was astonished, And the Galena was admonished, And their efforts to ascend the stream Were mocked at. “While the dreadful Naugatuck, With the hardest kind of luck, Was nearly knocked Into a cocked-hat.

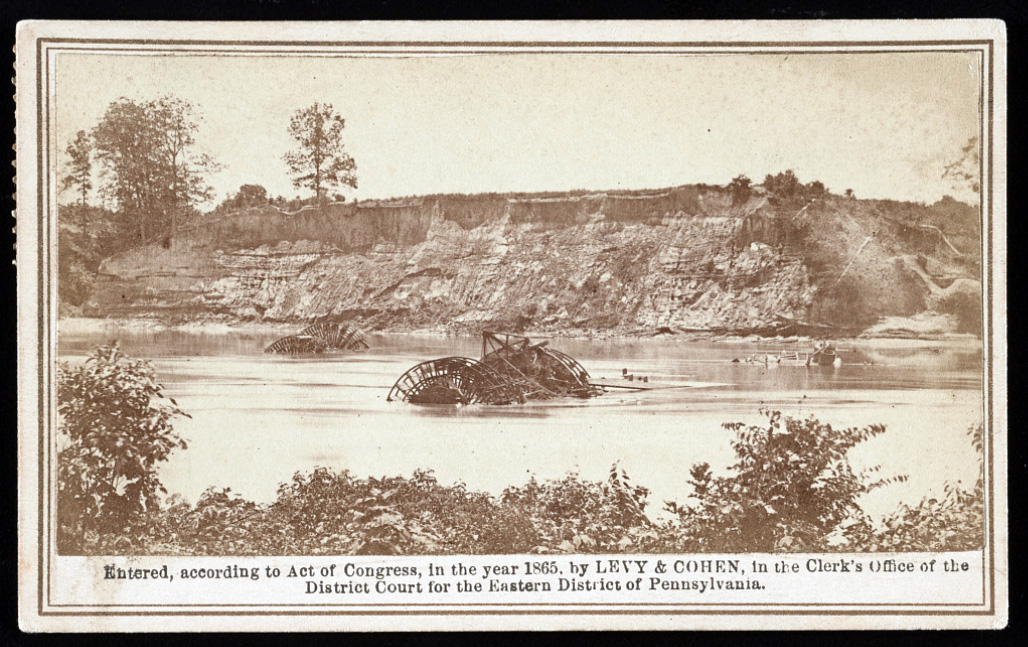

View of Fort at Drewry’s Bluff After the Battle by Levy & Cohen Philadelphia 1865

Image Courtesy of: Liljenquist Family Collection, Library of Congress

As the new year of 1862 marched out of winter and closer to spring, the Federal war effort had all but stalled in the Eastern Theater. Defeated at Bull Run in July 1861, and again at Ball’s Bluff in October, there was precious little to demonstrate that the Federal armies in the east could achieve a quick and victorious result. Beginning in August 1861, however, Major General George Brinton McClellan had been working tirelessly to build a strong army within his command of the Military Division of the Potomac. This new army, the Army of the Potomac, saw both its numbers and morale surge between McClellan’s arrival and the retirement of Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, the United States’s general-in-chief. With a minor victory in western Virginia earlier in the year, his work in the Department of the Ohio prior to that, and much political wrangling, on November 1, 1861, McClellan was promoted to general-in-chief in addition to his role as the Potomac army’s commanding general. But, by the early days of January 1862, McClellan had failed to share any strategic plans with the Lincoln administration, nor had he brought his army into battle. Finally forced to do so at a meeting with Lincoln on January 12, McClellan announced his strategic vision of an amphibious operation with the Army of the Potomac. Over the next two months, tensions between Lincoln, McClellan, and the cabinet escalated. Embarrassment hung itself on McClellan’s shoulders following the uncontested retreat of the Confederate army out of the Manassas area and to the Virginia peninsula. McClellan's grand campaign, now shared with his superiors, originally called for a strike along the Rappahannock River. The strategy was changed, however, to a campaign on Virginia’s peninsula all the way to the Confederate capital at Richmond. Finally, on March 17, 1862, portions of the Army of the Potomac left Alexandria, Virginia by boat, destination Fort Monroe.

McClellan’s slowness in implementing his strategy allowed Confederate forces around Richmond valuable time to construct defenses on land and on water, including the James River. As McClellan’s army prepared to board their boats in Alexandria, Major Augustus Harrison Drewry, Company C, 2nd Regiment Virginia Artillery, sought permission from Robert E. Lee to build a fort on his personal property in which his unit could deploy and in effect add yet another layer to Richmond’s defense in depth. With the defense of Richmond becoming ever more important with McClellan’s advance on the peninsula, Drewry raised a company of men from Chesterfield County. Drewry’s company was “composed largely of men who were beyond the age of conscription,” he later wrote.[1] Samuel A. Mann, a sergeant in the 2nd during the battle, wrote after the war, “The ages of the men of the company ranged all the way between seventeen to about forty-five or fifty years, and were, by occupation, mostly farmers, with a sprinkling of carpenters, cotton-mill hands, with some gentlemen.”[2] After their enlistment and “tender[ing] our services to the Governor,” Drewry’s company was “assigned to duty at Battery No. 19, on the turnpike, between Drewry’s Bluff and the city of Richmond.”[3] The excitement of going to war turned into the doldrums of inactivity. Drewry realized the post he had been ordered to “was unimportant, and that we would likely be called to field duty, for which I did not think my men were well suited….”[4]

Augustus, born in 1817, was a prominent Virginian by the time of the war. Residing at his grandfather’s plantation, Brandywine, in King County, Virginia in 1861, his landed wealth increased upon his marriage to his second wife, Mary A. Harrison, a descendent of Pocahontas. Augustus inherited the tract of land just eight miles south of Richmond by river from Mary.[5] The tract included a high bluff, over 100 feet high above the water, that was adjacent to the James River. Additionally, although the approach to where the fort would be built from the southeast and Hampton Roads consisted of a mile of straight waterway, at the bluff, there was a bend in the James River that provided any cannon on the bluff plunging fire on ships coming from that direction. A complement of guns placed here, however, could command that mile-long, straight section of the river below the bend. Furthermore, impediments and obstructions could be dropped into the river’s channel, further narrowing the physical area that Federal gunboats could utilize due to their drafts. Eventually, these obstacles would include sunken cribs filled with stones, pilings, and even the hulks of several sunken river-faring vessels. These efforts would slow the rate of speed at which Federal ships could safely move, thus allowing more time for the Confederate artillery to fire upon them. Additionally, they could significantly narrow the channel to the point that the Federal navy would have to remove these obstacles, under fire, if they wanted to continue towards Richmond. Although Drewry’s idea was to aide in Richmond’s defense, it was also with his command in mind as these men were well beyond the capacity for extended field service on active campaign. Lee, Drewry wrote, “readily agreed,” to his proposition for a fort along the James in this vicinity.[6] Now, before work could begin, and Drewry’s command placed in that defensive position, a location had to be selected.

According to an article in the News Leader in 1906, later reprinted in the Southern Historical Society Papers, “The following day,” March 16, Drewry was “accompanied by Major Rives and Lieutenant Mason, of the engineers department…down [to] the river to select a suitable position.”[7] The first location the trio looked at, Howlett’s at the head of the Horse Shoe, which formed Dutch Gap, was found unsuitable. Although this site provided good elevation, even depth of the river channel, and significant wood lots on each bank, review of river charts demonstrated that the Federals “might cut through at the Gap, and pass on up the river, and we would have to go above for our fortifications,” Drewry concluded.[8] The next location they reviewed for suitability was Drewry’s land, in particular the high bluff along the James River. Drewry’s Bluff was selected as the place for the fort and gun emplacements to be built. With the location settled, Captain Drewry marched his unit, the Southside Artillery to the bluff on March 17. “[W]ith drums beating and colors flying, accompanied with all our impediments, we were marched along the turnpike, down to Drewry’s Bluff, on the ‘Noble James river,’ about seven miles below Richmond,” Sergeant Mann wrote. That evening, Mann wrote, the men of Drewry’s company “bivouacked at the future ‘Gibraltar’. . .grumbling about the hard fate that had overtaken us, at having been turned out of our nice new houses and forced to make our beds on the bare ground.”[9]

Drewry later wrote after the war that the first task for his men and engineer Mason was the obstruction of the river, then the fort. The captain “furnish[ed] him [Mason] details from my company, who put in the cribbing, employing my team, labor and company to aid him, which was likewise done by other members in my command.”[10] “So the work went on pretty much,” Drewry recalled.[11] Quickly, however, the bureaucracy in Richmond and the Confederate military complex ground any real progress on the fort to a halt. Drewry discovered that his lack of authority in requisitions for construction, and low enthusiasm in Richmond for the project in general meant his full realization of the fort might not be met. He could not requisition wagons, or teams, or additional labor for construction outside of his own command. Regarding the channel obstacles, Tredegar Iron Works eventually provided iron bolts and shoes for the pilings to be constructed, but as a low priority, did not make or ship these important components in a timely or efficient manner. The lack of progress and support for the position depressed morale in Drewry and his command immensely. So much so, that instead of working on the construction of firing platforms for his guns, he had them work on constructing cabins for themselves. “Then Captain Drewry…hurried us on towards erecting log-cabins for quarters…. After a busy time, the quarters were finished, and occupied,” Sergeant Mann reported.[12]

Despite these challenges, though, some work for Drewry’s guns was completed. Mann noted that after Lieutenant Mason laid out the fort, work on “emplacements to hold three heavy guns were prepared on the river face of the bluff.”[13] These guns included a 10 inch Columbiad from Richmond that was placed on the western emplacement, an 8 inch, 64 pounders, and a 10 inch, 128 pounder.[14] An additional two eight-inch Columbiads, “were sent down the river on lighters, drawn by tugs, to the wharf, erected at the mouth of the ravine, just east of the fort.”[15] “Then the heavy work,” began, Mann recalled.[16] The company had to get the guns off the lighters and onto dry land, followed by the immense task of getting them up a steep incline-railway over 100 feet above the river. Eventually the guns were placed in their respective batteries but the chore of mounting them remained. Other projects in the fort’s construction had to be completed before this could happen. Mann remembered skilled workmen arrived to build foundations for the fort, level gun platforms, and traverse circles. All of this took time, and with few people employed in the work, it dragged on throughout the next several weeks. More progress was made after the arrival of Col. Robert Tansell, who directed the mounting of the guns on hand with “the aid of a ‘gin’ and much heavy pulling on ropes by hand.”[17] After nearly a month of only minor progress on Fort Darling at Drewry’s Bluff, renewed interest by Lee and Confederate authorities finally stimulated further work on the project.[18]

In mid-April, almost a month after the arrival of Drewry’s company at the bluff, a redoubled effort of work began. Three more guns arrived at Drewry’s position, in addition to another company of artillery. Much to Drewry’s chagrin, these additional men and materials did not stay long, as they were shortly ordered to Fredericksburg. Once again, “[s]o the work went on pretty much,” the same as before.[19] All of this changed, however, as General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, commander of the Army of Virginia, looked to evacuate the position he had created across the Virginia Peninsula at Yorktown. Months earlier Johnston had abandoned the northern Virginia front at Manassas, eventually taking his army down the peninsula to blunt the progress of McClellan’s march on Richmond. Late in April Johnston talked of abandoning the Yorktown line, increasing the need for other defensive points along McClellan’s route to Richmond, especially so for Drewry at Fort Darling. Thus, Lee, and Confederate Naval Secretary Stephen Mallory now turned their focus on completing Fort Darling. As one historian wrote, “Starting in late April, one or both would usually ride out daily to the bluffs to check on the work.”[20] Sergeant Mann wrote of this period that everyone at the fort was “kept busy until about the first of May.”[21] Now, after McClellan’s army had operated on the peninsula during the month of April, the Federal commander chose siege warfare to move the Confederate defenders out of their Yorktown line. McClellan’s shift in tactics were a result of faulty intelligence he had received from his field commanders and his own exaggerated ideas of Confederate strength along Johnston’s line. With the change in tactics, McClellan now ordered up his large siege guns to assail the Confederate position. Johnston believed yet again during McClellan’s push towards Richmond that his command’s numerical inferiority and lengthy line would not be able to hold against the Union juggernaut, especially in the face of massive siege artillery. Thus, in early May, Johnston’s retreat from the Yorktown line doomed the Confederate navy at Norfolk, a calamity that now “granted any sort of priority,” to Fort Darling’s completion, “and by then it was almost too late.”[22]

Meanwhile, Captain Drewry’s command began to receive regular drilling in the use and tactics of heavy artillery. Sergeant Mann remembered Robert Stuart McFarland as their instructor. A Scotchman, McFarland was “spare-built, and appeared to be about thirty-five years of age, who told us that he had been a soldier for sixteen years; first in England, and lately in the United States army….”[23] Now he worked with these Confederate artillerymen on “the manual of heavy artillery tactics, showing us how to go to our places for action, take implements, sponge, load, in battery, point and fire, and all of which motions we had to go through with ‘at double quick time.’”[24] Over the coming weeks the drilling never eased as McFarland worked these gunners “every day, and almost all day long,” but, he was not the only one to do so. Drewry also enlisted the help of a man by the name of McMellon, a former Ordnance Department officer in the English army. Like McFarland, McMellon also “came down to teach us what he knew about drill at the guns, and how to arrange the powder in the magazine, and the shells in their houses. He also taught us some hygiene exercises,” remembered Sergeant Mann.[25]

With the importance of the fort as a strong defensive position against any Federal effort to move on Richmond via the James River on the rise, both Lee and Mallory turned their full attention to its completion and compliment of men and guns. It seems that at last Confederate authorities recognized that if the Federal fleet passed Drewry's Bluff Richmond would have been at their mercy. The Federal navy by 1862 dominated anything that the Confederacy could bring to bear against it, either by land or sea. If any of their gunboats slipped past the bluff and steamed on to Richmond, the seat of the Confederate government, its leaders, and its defenders could potentially be driven not only from its environs, and maybe Virginia as well. By May 2, Lee ordered a company of sappers and miners to Fort Darling to increase the size of the garrison and further assist in its completion. Just shy of a week later, May 8, Secretary Mallory ordered Commander Ebenezer Farrand to take additional troops to the fort and to take command over all the forces there. Drewry remained in command of Fort Darling.These latest arrivals were composed of Confederate sailors and marines who had evacuated Norfolk. Drewry remembered that upon their arrival at Fort Darling on Drewry’s Bluff, these men were “terribly demoralized, and surprised that we should think of resisting those heretofore victorious and invincible gunboats.”[26] According to Drewry’s post war account of this moment, the sailors took “some persuasion [before] they were induced to stop with us, and planted themselves on the river above our fort, with assurance that we could take proper care of them.”[27] Of Farrand, Drewry was anything but impressed. “[H]e messed with me,” noted Drewry, “and would occasionally sally out to look after his defunct navy...and did not undertake to interfere with my command in the fort….”[28]

By now Darling’s defenses included three guns from the 2nd Virginia Artillery, five additional guns from other Confederate gunboats, including the Patrick Henry and Jamestown, a Confederate gunboat that was sunk in the river’s channel, as well as additional channel obstructions. The Patrick Henry provided the bluff’s defenses with “one of his eight-inch guns on the river bank, just above the entrance to the fort.”[29] Unfortunately, due to an extended period of rain throughout the previous days, and the day before the battle, this gun’s “whole superstructure fell in, and we lost the benefit of his help until the fight was nearly over,” Drewry recalled.[30] With mid-May on the horizon, McClellan’s army bearing down on Richmond, and the Federal navy approaching down the James, Drewry’s Bluff became a hornet’s nest of activity. “The Confederate authorities and the City Council of Richmond had in the meantime become alive to the importance of our work,” Drewry recalled, “and gave us considerable help to its completion.”[31] On May 11, Robert E. Lee ordered additional heavy artillery to Chaffin’s Bluff, yet another layer in Richmond’s defense on the James River. These men, six companies in all, began digging gun emplacements immediately upon their arrival. More reinforcements arrived the following day. Naval Secretary Mallory sent the crew of the recently scuttled CSS Virginia and Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones to continue to bolster Darling’s defense. With the arrival of a large Union force at Fort Monroe and advancing down the peninsula, McClellan’s forces placed the Virginia towns of Norfolk and Portsmouth within threat of capture. At Norfolk rested the Confederate naval yards. Instead of leaving the yards intact, including ships of war, those vessels that could escape were ordered out. Those that could not, as well as the naval yards, were set ablaze lest they fall into Federal hands. The Virginia was one such vessel that could not escape, those she was scuttled and her crew and resources sent to Darling. Thus, Jones assisted in placing a nine-inch Dahlgren gun in position just around the bend in the river, but the gun proved to be too far out of range to be of use during the battle.

The continued work on Darling’s completion was kicked into overdrive on May 13. Around noon on that Tuesday, Mann recalled that a steamer stopped opposite the battery to alert them that five Federal gunboats were moving towards their position from Harrison’s Bar. The news sparked every man and officer into further efforts to complete the defenses. There “was hurry and some confusion,” wrote Mann, “but we kept on steadily, making preparation to defend the fort. I think we loaded all three guns this day.”[32] An attack that day did not come. The following day, however, two more companies of Confederate marines arrived at Darling. Across the river, at the same time, a company of the Washington Artillery was sent to bolster the defense at Chaffin’s Bluff. On May 14, orders arrived from Confederate Secretary of War George Wythe Randolph at Brigadier General Benjamin Huger’s headquarters to send Brigadier General William Mahone’s Virginia Brigade forward to these positions as well. The concern was Federal navy transports bringing infantry down the river and unloading them to attack the gun batteries. Thus, with Mahone’s brigade at Darling, there would be sufficient Confederate infantry support to thwart any attempted infantry assault against them.[33]

The additional reinforcements could not come soon enough. As these orders were winding their way through the chain of command, at approximately noon, a shell screeched high over the fort. Federal gunboats had arrived to within range of the fort yet remained out of direct line of sight at their location on the river east of Fort Darling. The shell, “of gigantic size,” startled those within Drewry’s defenses. For many, it was the first hostile fire they had ever heard. The tense moments that slowly ticked by after the sound of the shell crashing in their rear drove everyone to states of high alert and focus. No further shots followed the first, however. Guns were manned while others continued working on the fort’s defenses. They worked long into the night, but were “told before [they] retired to [their] quarters that a signal shot would be fired by the sentry on post at the battery, as a signal, that the hostile boats had appeared…and to warn us to hurry to the fort, and to take our places at the guns.”[34] The signal shot was not needed, and although “most of us slept very well,” wrote Sergeant Mann, “some of the men were kept at work all night.”[35]

By all accounts the morning of May 15, 1862, dawned wet and soggy. Writing from his headquarters, Army of the Potomac commander George B. McClellan, relayed to Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton that not only had it rained the previous day and night, but rain had continued into May 15 as well. “Very cool, wet, and dreary,” McClellan concisely wrote.[36] In his private correspondence, however, McClellan further described the weather conditions that would linger throughout the day. “It rained a little yesterday morning, more in the afternoon, much during the night, and has been amusing itself in the same manner very persistently all day,” the general confided.[37] In short, McClellan wrote, the morning of May 15 promised to be “Another wet, horrid day!”[38] The USS Galena, which at the time was making its way towards Fort Darling, reported a “slight rain.” At Fort Darling, Sergeant Mann recorded “some light showers” were falling as the day dawned cloudy and wet. Up early, he did not mind the weather as his mess was eating breakfast. All of that would change, and quickly, as Mann and the rest of his mess ran towards the fort with biscuits in hand upon the crack a of signal musket being fired. It was against this backdrop that the first battle at Drewry’s Bluff and Fort Darling was waged, and where Captain Drewry’s defenses were tested.

Sergeant Mann and the rest of his mess arrived at the fort, to see a “working party toting sand-bags…and placing them so as to form embrasures to the gun.”[39] The signal musket shot was not in error, Federal gunboats were spotted and were moving towards Fort Darling. Mann and the others were ordered to assist with the sandbags, continuing to stack them right up until the last moments before the guns on both sides opened. Gun crews took their positions, others brought powder from the magazines, while still others handed up the shots. Mann recorded those moments:

Captain Farrand, the naval officer, Captain Drewry, with Lieutenant Wilson, took their stations at my gun (No.2), Lieutenant Jones also stayed there some; we were well looked after. Captain Jordan, of the Bedford Artillery, with his men, took charge of the ten-inch (Gun No. 3)…Thus we stood, ready for the word to “commence firing” at the proper time.[40]

From the time the Federal gunboats were first spotted, between 6:00 and 6:30 a.m., and over the next hour as they further approached Chaffin’s and Drewry’s Bluffs, the Confederates had yet to receive the word to fire their guns. Now, nearing 7:45 a.m., the USS Galena and USS Monitor reached a position just 600 yards from the bluff. The Galena, Commander John Rodgers commanding, ordered her anchors dropped in the channel as she took a position broadside to Fort Darling. Before the Galena could finish going into position, the guns on top of Drewry’s Bluff opened on her. Captain Ebenezer Farrand, in command of both the Confederate army and navy forces at Drewry’s Bluff, gave the order to fire, and scored two hits against the Galena, striking her port bow. The shells killed and wounded the entire gun crew on one of guns that was being prepared to make the Galena’s first strike against Fort Darling. It was at this time that United States Marine Sergeant John Freeman Mackie, in command of twelve Marines, led them onto the gun deck to take over working these guns and getting them back into the fight. The Marines remained at these guns for the remainder of the battle and Mackie was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. Meanwhile, the Monitor worked to get into position as well. As she neared the obstructions in the channel of the James River, now within 400 yards of the Confederate position on the bluff, two problems emerged. First, the obstructions would need to be dealt with, but that would require sending out work parties onto her deck. Those work parties would need to have artillery support from the guns on the Monitor to provide covering fire. At her current position, though, the artillery could not elevate the gun tubes high enough to reach the fort and its batteries so the Monitor could not move into position to support the Galena. Thus, the Monitor had to move towards a new position to where her guns could be brought to bear. All of this took time.

Meanwhile, three wooden Federal gunboats also arrived within range to engage with Drewry’s guns. These three ships included the Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck. All of them engaged the bluff at much further distances than did the two ironclads. The Aroostook and Port Royal engaged at an even further distance from the bluff batteries than the Naugatuck. Commander John Rodgers, in charge of this squadron of ironclads and wooden gunboats, quickly realized that it was not just the guns at Drewry’s Bluff that he, his craft, and his men had confronted. Rodgers, on the Galena, later wrote in his official report of the battle that they found “The banks of the river…lined with rifle pits, from which sharpshooters annoyed the men at the guns.”[41]

By now in the engagement, all the batteries on the bluff had opened upon the Federal squadron. Sergeant Mann’s battery had already opened fire on the orders of Farrand and “Gun No. 1 had also been ‘fired,’ presumably with good results as its gunner was considered an expert….”[42] Shortly into the battle, Captain Jordan’s ten-inch gun was knocked out of action. The recoil of the gun nearly dismounted it, and it took nearly the rest of the battle before they got it back into firing condition. Troubles continued to plague the batteries on top of Drewry’s Bluff. The naval gun that had been brought in to further strengthen this position was also knocked out of action. This gun’s casemate, constructed of heavy logs, caved in on it. With two guns disabled, only the two eight-inch guns of Captain Drewry’s company, firing 64-pound shells, were left to contend with the ironclads and gunboats. Mann later recalled that the sounds from both sides firing these massive shells, their impacts, and explosions “was the most startling, terrifying and diabolical sound which I had ever heard or ever expected to hear again.”[43]

Despite the setbacks with some of the guns of the Confederate artillery, and facing off against ironclads, Drewry’s company began to have an impact on the Galena. After numerous shots “glanced off,” but leaving “a visible scar on the boat,” a round finally penetrated Galena’s armor, “coming out of and tearing up her deck, after glancing up, having been deflected by something inside of her hull.”[44] Commander Rodgers wrote in his official report that the entirety of the engagement, “demonstrated that she [Galena] is not shot-proof.”[45] As the Confederate batteries continued to strike Rodger’s ironclad, the damage to it and the resulting casualties quickly became apparent.

[B]alls came through, and many men were killed with fragments of her own iron. One fairly penetrated just above the water line and exploded in the steerage. The greater part of the balls, however, at the water line, after breaking the iron, stuck in the wood. The port side is much injured; knees, timbers, and planks started. No shot penetrated the spar deck, but in three places are large holes, one of them a yard long and about 8 inches wide, made by a shot which, in glancing, completely broke through the deck, killing several men with fragments of the deck plating.[46]

Other ships in the Federal squadron also suffered damage and casualties, from both rifle and artillery fire. Over on the USS Port Royal, Lieutenant George Upham Morris wrote, “the enemy’s riflemen opened upon us from the woods, their bullets piercing our bulwarks. Returned their fire with a few shots from our 24-pounder howitzers, which had the effect of silencing them.”[47] Although Morris was able to silence the Confederate rifle fire for the time being, he was unable to silence the Confederate batteries that were still firing on his boat. Morris remembered after the battle that Drewry’s gunners were effective and exceedingly accurate. “One shell,” he reported, struck “us on the port bow below water line. The water flowed in freely, so that it was necessary to draw off in order to repair damage….”[48] The U.S. revenue steamer, the E.A. Stevens, also known as the Naugatuck, reported being “under quite a heavy fire of musketry, which was constantly returned by us with shell and canister from our light broadside guns.”[49] Lieutenant David C. Constable, in command of the Naugatuck, also engaged with Drewry’s guns “until the bursting of our own gun.”[50] The rate of fire aboard the USS Aroostook slowed significantly as well. Lieutenant J.C Beaumont, its commander, “had the mortification to find that many of the sabots of my XI-inch shells were too large to enter the gun, a circumstance which caused much delay in serving.”[51] The guns on Drewry’s Bluff quickly took advantage, finding the Aroostook’s exact range. Beaumont was forced to move the gunboat another 100 yards further downstream before he could safely return fire.

As the battle wore on, Confederate casualties mounted as well. Sergeant Mann and Lieutenant Wilson both had close calls. Wilson was injured when a federal shell burst through the sandbags near his gunner’s position, and Mann tripped and fell over the rammer while running, hitting the hard gun platform in a heap. Captain Jordan and seven of his men, all sailors with the Confederate navy, were killed while they were trying to remount their gun during the battle. The fire from the Federal navy “battered the parapets of the fort badly, and also shot our large flag to pieces and cut down trees of all kinds and sizes,” Mann recalled.[52] All the while Captain Drewry was conspicuous among his company. One account stated that he was, “Mounted on the fortifications…command[ing] and encourag[ing] his men during the entire engagement, directing the fire of his guns with such skill that success was assured.”[53] The same account shared that Drewry “refused to heed the earnest and repeated pleading of his men to come down from his dangerous position, and calmly allowed the shot from the enemy’s batteries to fall like hail around him.”[54] From these works, Drewry’s voice rang out above the din of battle. “Fire on those wooden boats and make them leave here,” the captain bellowed.

The battle at Drewry’s Bluff had raged for nearly four hours. Sergeant Mann estimated the time as 11:05 a.m. when he witnessed the three wooden Federal gunboats turn and start to steam away from Fort Darling. Not far behind were the two ironclads, Monitor and Galena. On the Galena, Commander Rodgers wrote in his official report of the battle that by 11:05 a.m. she “had expended nearly all her ammunition,” thus, “I made signal to discontinue the action.”[55] When the Monitor turned and began to head away from the bluff, one Confederate was heard to yell at her, “Tell the captain that is not the way to Richmond.”[56] The command of “cease fire” spread down the line from the lips of Captain Farrand and one by one the Confederate guns on the bluff fell silent. Immediately the defenders “tossed our caps into the air, and shouted our cry of victory,” Mann recalled.[57] But Drewry recognized the possibility that this fight could be far from over. “Don’t a man leave for the quarter, for I want you to fix up these parapets that have been knocked down, and those sandbags torn to pieces, must be replaced and get ready for them, for the boats will probably be back here again,” Drewry told his gunners.[58]

While Drewry set his men about making repairs as the sounds of the battle trailed off, both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Lee arrived at the bluff. Eventually they made their way to Gun No. 2’s position. Seeing the damage this emplacement had sustained during the battle, and Drewry’s men hard at work on making repairs, “The General showed us how to replace the sand-bags,” Sergeant Mann recalled.[59] Hours ticked by, and with each that passed, the threat of the Federal navy returning to try a second attempt at passing the batteries decreased. The battle for Drewry’s Bluff was over, and its true cost became apparent.

In all the Monitor was struck three times by the Confederate guns on the bluff. Lieutenant William Nicholson Jeffers, the ironclad’s commanding officer, submitted the following regarding the damage she received during the battle, “She was struck three times; one solid 8-inch shot square on the turret, two solid shot on the side armor forward of the pilot house, neither caused any damage beyond bending the plates. I am happy to report no casualties.”[60] Jeffers realized, however, that the engagement produced very little gains despite the demonstration of superior conduct by the sailors on board. “In conclusion, permit me to say that the action was most gallantly fought against very great odds and with the usual effect against earthworks,” he wrote. “So long as our vessels kept up a rapid fire they rarely fired in return; but the moment our fire slackened they remanned their guns. It was impossible to reduce such works except by the aid of a land force.”[61] The Federal army would not provide one that day.

The USS Monitor’s ironclad sister, the Galena suffered far more damage and casualties. During the nearly four-hour engagement, she was struck 44 times. In addition to rounds piercing her armor, exploding below deck, splintering her wooden components, and taking on water, she also caught fire for a brief time during the battle. Commander Rodgers credited J.W. Thomson with not only repairing some broken valve gear during the battle, all while under fire, but “under his directions a fire in the steerage, caused by an exploding shell, was extinguished before the regular firemen reached the place.”[62] The staggering damage to the Galena was also reflected in her casualties, 14 dead or mortally wounded and 10 injured. Among those casualties were the men under the command of Acting Master Benjamin W. Loring. “Loring handled his division with great bravery,” Rodgers wrote in his official report, “The port side tackle of his after gun was three times manned afresh, all the men having been twice either disabled or killed.”[63] Another casualty aboard the Galena that day was a Mr. Boorom, a gunner. Boorom was “was killed by the fragment of a shell at the close of the action, was cool and very efficient,’ Rodgers remembered of him. Rodgers made a special statement of Boorom, “In him the service has lost a very valuable officer.”[64]

Despite the destruction aboard the Galena, she did land several destructive blows to Drewry’s Bluff’s defenses and gun crews, inflicting seven killed and eight wounded. Commander Rodgers praised his men for their actions during the battle. “I can not too highly commend the cool courage of the officers and crew,” he wrote.[65] In particular, Rodgers cited T. Millholland, an assistant engineer in command of the steam fired department on the ironclad, as not only an “active and efficient” sailor, but also doing “good service” as a sharpshooter firing on those Confederates lining the banks of the river. Rodgers also wrote of “Mr. Jenks, master's mate, in charge of the small-arm men, was very useful. A number of the enemy's sharpshooters were shot; at least six were counted.”[66] Charles Kenyon, a fireman abord the Galena was noted in the official report of the Galena’s participation in the battle for his “conspicuous for persistent courage in extracting a priming wire, which had become bent and fixed in the bow gun, and in returning to work the piece after his hands, severely burned, had been roughly dressed by himself with cotton waste and oil.”[67] Jeremiah Regan, quartermaster, and captain of No. 2 gun acquitted himself so well during the battle that Rodgers for an appointment as master’s mate. He also cited the Marines for their efficiency with their muskets that day, and along “with the coal heavers, when ordered to fill vacancies at the guns, did it well.”[68]

One Marine Rodgers did not mention in his report was Sergeant Mackie. Although the 26-year-old silversmith from New York City did receive much recognition just eight weeks after the battle when President Lincoln, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and several other high ranking political and military officials arrived at the Virginia Peninsula in July. While visiting the Army of the Potomac, these notables, along with Captain Rodgers boarded the Galena to inspect the ship. Still bearing the scars of the May 15 battle, Lincoln asked out loud, “I cannot understand how any of you escaped alive.”[69] Before leaving the Galena, the visiting party stopped to thank the officers and crew for their service, and Lincoln made a short speech. Captain Rodgers then had several men report to the main-mast, among them John Mackie. “Mr. President, these are [the] young heroes of [the] Fort Darling battle,” Rodgers pointed out. He then told Lincoln and the others gathered there a little bit about each of their actions during the May 15 fight. Of Mackie, Rodgers described “how in the terrible crisis Mackie had rallied the marines and taken charge of the after division when all the men had been killed or wounded.” Lincoln shook each of the men’s hands, thanked them, and then ordered Naval Secretary Welles to ensure that each of these men were promoted and received the Medal of Honor. Three Medals of Honor were awarded.

Mackie was promoted to orderly sergeant later that November, and received the Medal of Honor on July 10, 1863. Sergeant Mackie was awarded the Medal of Honor for his “gallant conduct and services and signal acts of devotion to duty.” His medal was shipped to him via the mail, finally catching up to the Marine that October. Now stationed aboard the Seminole, which was then anchored off Sabine Pass, Texas, a ceremony was held on the quarterdeck of the ship in which the medal was officially presented and awarded to Mackie. He was the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor. Of the service of all of those aboard the Galena on May 15, 1862, Rodgers noted, “To particularize the good conduct of the crew is difficult. Where the men behaved so well, it is impossible to mention names without sending a muster roll.”[70]

On the Port Royal, their captain was wounded by Confederate rifle fire from one of the banks, with some sources crediting a sharpshooter. The Royal also received a direct hit by a shell to the port bow below the water line. Their commander, Lieutenant Morris, reported that after the shell found its mark, “The water flowed in freely, so that it was necessary to draw off in order to repair damage.”[71]

The last-minute push to complete the works at Drewry’s Bluff and rush reinforcements of men and guns to the position no doubt greatly contributed to the Confederate victory on May 15, 1862. One historian estimated nearly 1,800 Confederate soldiers and sailors were stationed at Drewry and Chaffin’s Bluffs that day, with an additional 4,000 reinforcements under the command of General Mahone marching steadily towards the fort.[72] The total number of guns had also drastically increased since Drewry and his company’s arrival in March. In all, twelve guns were brought to bear in various degrees of completed embrasures. Further measures, such as sinking the Jamestown in the channel also aided materially in closing the door on the water approach to Richmond via the James River. Historian Steven Newton, though, argued that the Confederates on May 15 fought two battles, one against the Federal navy, and the other against a chaotic and ineffective command structure at the bluff. Newton wrote, “Farrand had been superseded by Sidney Smith Lee, who only arrived on the morning of May 15. Mahone was also coming to take command as Captain Drewry and the other army officers studiously ignored Commander Tucker, who had taken effective control of the navy work parties.”[73] Perhaps it was Captain Drewry and the men of the Southside Heavy Artillery that successfully held the defensive together and materially added greatly to the victory that day.

One former Confederate veteran wrote of the battle in 1901 that indeed it was “The men who bore the brunt of that fight,” all “substantial farmers from the surrounding country, not caring for the attainment of military glory, but well satisfied to know that they had rendered important service to their country, and stood for their friends and firesides against our common enemy; and this statement is made in justice to them, whilst yet they have the evidences to substantiate the facts.”[74] Another Confederate added at the turn of the century, “The men of Chesterfield who composed the Southside Heavy Artillery, commanded by Augustus H. Drewry, who drove back the iron-clad fleet down the James river on that momentous day are justly entitled to the laurel wreath of victors, and should ever be cherished in the hearts of their countrymen.”[75] Many cited Drewry’s actions and command style that day that ultimately led the Confederates to victory. The battle “established the reputation of Major Drewry as a man of courage, coolness, and resource,” wrote one who was at the battle in an 1899 published account.[76] Sergeant Mann credited all who aided in the defense that day, writing, “And the behavior of the officers and men of the company on that occasion, under the circumstances, was extraordinary.”[77]

With the May 1862 battle of Drewry’s Bluff, “A glorious victory over the hitherto invincible navy of the United States was achieved and the fall of Richmond was prevented, for if the Federal gunboats had succeeded in passing Drewry’s Bluff on that day the capital of the Confederacy would have at once been at their mercy, and the Confederate troops would have been compelled to retreat from Richmond, and probably from Virginia.”[78] Yet, perhaps it was a post war poem by Sgt. Samuel Mann that summed up the battle and the Confederate victory thereof best:

“The Monitor was astonished,

And the Galena was admonished,

And their efforts to ascend the stream

Were mocked at.

“While the dreadful Naugatuck,

With the hardest kind of luck,

Was nearly knocked

Into a cocked-hat.”[79]

****

[1] A.H. Drewry to Judge W. I. Clopton, in William I. Clopton, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” Southern Historical Society Papers, 34, (January-December 1906): 83.

[2] Samuel A. Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” in William I. Clopton, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” Southern Historical Society Papers, 34, (January-December 1906): 86.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “The Last Roll,” in Confederate Veteran, 7, no. 10(October 1899): 461, a notice of the passing of Augustus Henry Drewry was published. In the short biography of his life that is provided, it states that after the marriage to his first wife, Lavina E. Anderson, Augustus purchased the farm which included the bluff. Additionally, it states that it was on this property where Drewry resided when the war broke out in 1861. Yet, it neglects to record her death, or Drewry’s remarriage to Harrison. This article contradicts numerous other biographies of Drewry and the history of his ownership of the property that was later used for the defense of Richmond.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., 84.

[9] Samuel A. Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,”87. The unit’s previous position, at Battery No. 19, on the turnpike, a little south of Manchester, had included two-room frame houses for quarters. These were a luxury to field units that the company had just finished construction on prior to being ordered to Drewry’s Bluff on March 17.

[10] Drewry to Clopton, 84.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 87.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 88.

[15] Ibid., 87.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Steven H. Newton, Joseph E. Johnston and the Defense of Richmond (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 157.

[20] Newton, Joseph E. Johnston, 158.

[21] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 88.

[22] Newton, Joseph E. Johnston, 158.

[23] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 86.

[24] Ibid., 86.

[25] Ibid., 87-88.

[26] Drewry to Clopton, 84.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., 85.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid., 84.

[32] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 89.

[33] Newton, Joseph E. Johnston, 158.

[34] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 89.

[35] Ibid.

[36] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 11, part 3, p. 174 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 11, pt. 3, 174).

[37] George B. McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story: The War For the Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It, and His Relations to It and to Them (New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887), 356.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 90.

[40] Ibid., 90-91.

[41] United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), Series I, volume 7, p. 357 (hereafter cited as O.R.N., I, 7, 357).

[42] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 92.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] O.R.N., 1, 7, 357.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid., 363.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid., 364.

[50] Ibid., 363.

[51] Ibid., 366.

[52] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 97.

[53] “The Last Roll,” in Confederate Veteran, VII, no. 10 (October 1899): 461.

[54] Ibid.

[55] O.R.N., 1, 7, 357.

[56] Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992), 94.

[57] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 94.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid., 95.

[60] O.R.N., 1, 7, 362.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid., 368.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid., 358.

[66] Ibid., 368.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

[69] W.F Beyer and O.F. Keydel, eds., Deeds of Valor: From Records in the Archives of the United States Government, 2 vols. (Detroit: The Perrien-Keydel Company, 1903), 2: 29-30.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Ibid., 358.

[72] Newton, Joseph E. Johnston, 158.

[73] Ibid.

[74] A.H. Drewry, “Drewry’s Bluff Fight: A Letter from the Late Major A.H. Drewry on the Subject,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 29, (January-December 1901): 285.

[75] William I. Clopton, “New Light on the Great Drewry’s Bluff Fight,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 34 (January-December 1906): 98.

[76] “The Last Roll,” in Confederate Veteran, 7, no. 10 (October 1899): 461.

[77] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,”95.

[78] Clopton, “New Light,” 97-8.

[79] Mann, “Sergeant Mann’s Account,” 95.

If you can read only one book:

Newton, Steven H. Joseph E. Johnston and the Defense of Richmond Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Books:

Bearss, Edwin C. River of Lost Opportunities: The Civil War on the James River, 1861-1862. Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1995.

Beyer, W.F. & O.F. Keydel, eds. Deeds of Valor: From Records in the Archives of the United States Government, 2 vols. Detroit MI: The Perrien-Keydel Company, 1903, 2: 25-30.

Browning Jr., Robert M. From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Burton, Brian K. The Peninsula & Seven Days: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007.

Coski, John M. Capital Navy: the Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron. Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996.

Donnelly, Ralph W. The Confederate States Marine Corps: The Rebel Leathernecks. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, 1989.

Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

Sullivan, David M. The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—The Second Year. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1997.

Symonds, Craig. Union Combined Operations in the Civil War. New York: Fordham University Press, 2010.

United States War Department. United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), Series I, volume 7.

Southern Historical Society Papers, 34, (January-December 1906): 82-98.

Southern Historical Society Papers, 29 (January-December 1901): 284-5.

Organizations:

Richmond National Battlefield Park

The Richmond National Battlefield Park preserves, protects, interprets, and commemorates Richmond Civil War battlefield landscapes, struggles for the capital of the Confederacy associated with the 1862 Seven Days’ Battles, the 1864 Overland Campaign, and the 1864–65 Richmond and Petersburg Campaigns, including the American military, social, and political history as exemplified by the New Market Heights Battlefield. Their mailing address is 3215 East Broad Street, Richmond, Virginia 23223, 804 226 1981.

Richmond Battlefields Association

The Richmond Battlefields Association (RBA), established in 2001, is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization dedicated to the preservation of historic Civil War sites surrounding Richmond, Virginia. Their mailing address is: Richmond Battlefields Association PO Box 13945 Richmond VA 23225, 804 496 1862.

Web Resources:

Overview of Drewry’s Bluff from 1862-1864 written by the National Park Service.

Overview of the May 15, 1862 battle at Drewry’s Bluff written by the National Park Service.

A detailed article of the events before the battle, the battle itself, and its aftermath.

An article by Gerald S. Henig published by the U.S. Naval Institute of the role of the Marines, both US and CS, at the battle.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.