Federal Army Rations

by R. E. J. Myzie

It was the responsibility of the Federal government’s Subsistence Department to ensure that Union soldiers were adequately provisioned and during the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War the army had codified a workable supply system to achieve this. Rations for permanent forts were quite different from marching rations. There was a much greater variety of foodstuff at forts or long-term encampments than there was in the field. Field rations had to survive without spoilage under sometimes adverse conditions. The army was careful about spending and took care to ensure that it got its money’s worth when it came to purchasing anything. Manuals and guides were published for commissary officers and commissary sergeants to assist them in evaluating the quality of purchases. Rations issued by the army included hardtack, soft bread, salt pork, salt beef, coffee, sugar, salt, pepper and vinegar (for flavoring and as a preventative of scurvy). Armies were sometimes accompanied by herds of beef cattle, which were slaughtered for fresh meat. Soldiers supplemented army rations with purchases from sutlers, packages from home, purchases from friendly civilians, and looting food in enemy territory. New forms of food were introduced and included an instant coffee in a thick paste, desiccated compressed potatoes, and desiccated compressed vegetables. There were no soldiers classified as cooks and soldiers on the march formed 3- or 4-man messes and took turns cooking for themselves. Regulations governing rations were detailed and included specified amounts of rations to be issued, forms to be completed concerning the purchase, delivery and consumption of rations by army units. A review of the text of the regulations shows that the government was extremely thrifty in issuing supplies of every kind and made great efforts to prevent fraud. Given the circumstances and the need for expediency in raising, supplying, and feeding a very large army in a short period of time, the government did well in working through the myriad of obstacles. Federal soldiers may have gone hungry from time to time, yet no one starved.

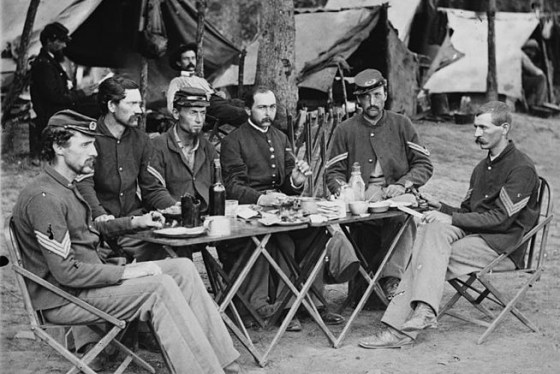

Bealeton, Va. Officers and noncommissioned officers' mess of Co. D, 93d New York Infantry by Timothy H. O'Sullivan August 1863

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Nearly everyone is familiar with Napoleon’s statement that an army marches on its stomach but there are necessities more important to the army to accomplish its mission than soldiers’ stomachs.Nevertheless, people have to eat and it was the responsibility of the Subsistence Department to meet that requirement—ensuring that soldiers were adequately provisioned.At the beginning of the Civil War the US Army’s total strength was slightly more than 16,000 men.Since the majority were scattered here and there in small western forts keeping an eye on the Indians, resupply was relatively simple.

During the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War the army had codified a workable supply system in an effort to ensure everyone throughout the army received a fair share of palatable food at an economical cost to the government. The Subsistence Department functioned reasonably well most of the time. Captain James M Sanderson, Commissary of Subsistence of Volunteers, wrote:

No army in the world is so well provided for, in the shape of food, either in or quantity or quality, as the army of the United States, and very little attention on the part of the cook will enable him to lay up a liberal amount weekly to the credit of the Company Fund. No man can consume his daily ration, although many waste it; and a systematic issue will, in a great measure, prevent unnecessary extravagance.[1]

Looking through many soldiers’ diary entries though, one might wonder how it was that the entire army hadn’t perished from food shortages or contracted scurvy for want of vitamin C.

Field Rations

Soldiers made very frequent references to food and rations in diaries and letters home. Herewith an assortment of comments:

Sun 9th (November)

I slept well last night we are all out of rations the whole Regt Some of the Boys were out today foraging and brought in three Sheep. I made my meals on mutton and thought it was ecellent when at Home I would not eat it. [2]

19th Nov 1861 Salt beef and potatoes

20th Fresh beef and rice soup

21st Salt pork and beef soup

22nd Fresh beef and pea soup

23rd Salt beef

24th Fresh beef and rice with raisons [3]

Fri Dec 12th …here garlick is plenty I gathered some and eat for Supper, as I’m very hungry for vegetable of Some Kind. [4]

Wedns. Feb. 11th …We Drew two Days Rations of Soft Bread. it is said we will have Soft bread regular now one day in five. This evening we had a mess of onions ...[5]

Frid Feb 13th …I fried a fish for breakfast…I went down to the Sutlers and bot. .10 cts Apples. .10 cts Cakes. .10 cts oranges. Afterward I bot .25 cts worth of Apples. … [6]

Rations intended for fortifications were by and large delivered in a timely manner. (Fort Sumter was one exception. Confederate forces in Charleston SC were able to fire on ships attempting resupply of the fort, effectively forcing Fort Sumter to surrender to the Confederates.) Rations for permanent forts were quite different from marching rations. There was a much greater variety of foodstuff at forts or long-term encampments than there was in the field. Field rations had to survive without spoilage under sometimes adverse conditions. Dairy products and fresh vegetables didn’t qualify. They spoiled too readily.

Soldiers on the march or in the field were issued hardtack or soft bread, pork or beef frequently preserved in brine, and were also issued coffee, sugar, salt & pepper, and vinegar as an antiscorbutic as well as a seasoning since the issue ration had little if any vitamin C. Candles and soap were part of the issue as well. Three days field rations were typically issued at one time.

The army was careful about spending and took care to ensure that it got its money’s worth when it came to purchasing anything. Manuals and guides were published for commissary officers and commissary sergeants to assist them in evaluating the quality of purchases.

As happens today, large quantity purchases were made from the lowest bidders, which left the way open for all kinds of attempts to defraud the government, by attempting to sell by short weight, inferior ingredients, adulterated products, and shoddy workmanship. As an example, in the early stages of the Civil War soldiers were issued unroasted, unground coffee beans to discourage suppliers from adding dirt or other contaminants to ground roasted beans. (Suppliers could sell perhaps 4¾ pounds of ground coffee and ¼ pound of dirt or sawdust.) Flour might have chaff ground up with the wheat, and so on. Another practice was to put old or even spoiled meat in the bottom of meat casks, with good meat on top. A diligent purchasing agent would open a few random casks to examine the contents before accepting delivery. A lethargic or careless one might not. While not necessarily widespread this practice was common enough that the army published warnings to subsistence and commissary officials to watch for it.

Carbohydrates

Not by bread alone does man live, and in the army there were substitutions available. Potatoes, rice, corn meal were issued, particularly at permanent stations. As with all rations, daily allocations per man were carefully spelled out.

Hardtack (hard bread) was a staple in the field. Hardtack is basically a plain flour and water cracker, baked hard and usually dried well. It was shipped in wooden crates weighing fifty pounds. Hardtack was made in commercial bakeries. If the hardtack was not well dried before being crated or was left outside on a dock or railroad platform in the rain, there was a likelihood of it becoming moldy or soft before it reached its destination. Hardtack was extremely hard, (soldiers called them “tooth dullers”; one of the more charitable terms used) and they became the source of countless jokes. They even furnished the lyrics for a song, Hard Crackers Come Again No More—a satirical parody of the popular song by Steven Foster, Hard Times Come Again No More. Recipes were published for the use of hardtack as an ingredient. Along with dulling teeth, it could be used as a thickener for soup or stew, a base for bread pudding and so forth. And if the hardtack was unappreciated, the crates it came in as a source for useful pieces of wood were.

Despite the near universal presence of hardtack in the field, the army did its best to provide soft bread to solders as well. Portable ovens followed the army and as often as was practical, soft bread was baked and distributed. There were also published plans to build field ovens.

Meat

Meat fell into a category all its own. The government purchased large quantities of salt pork and salt beef. Neither was particularly palatable. Accounts from the time suggest that salt beef was much worse in flavor than salt pork – so much so that soldiers referred to it as salt horse. Indeed, it was so salty that, if the men were near a river or stream, they would tie a string to the beef and throw it into the river overnight in hopes of flushing out some of the salt. To negate the inedible meat problem, the army, wherever possible and practical, marched with a herd of beef cattle following behind. When the army stopped, so too did the cattle, and sufficient beeves were slaughtered to provide fresh meat to the troops.[7]

Beverages

Coffee, and sometimes tea was issued. When the troops were issued green coffee beans they had to roast them in a pan over a fire, and then grind them between two hard surfaces. A rifle butt made an acceptable pestle. To economize, men made “coffee bags” similar to tea bags. After the coffee was brewed the bags containing the used grounds could be retrieved from a cup or pot, dried, replenished and used to make more coffee. Brewing coffee took on some significance. Frequently when a marching column stopped to rest, immediately men would gather and ignite twigs, add coffee and water to a tin cup and boil it. If it hadn’t yet boiled when the order came to move again, they drank it anyhow. There was also instant coffee manufactured by, among others, G. Hummel, called Extract of Coffee. It was a very thick paste of coffee and Borden’s sweetened condensed milk. A spoonful added to a cup of hot water made passable café au lait. [8]

Condiments

Sugar, salt, pepper, and vinegar were issued. A common practice among soldiers was to mix the coffee and sugar together so as not to run out of one before the other. Salt and pepper were issued in very small quantities per man so it made sense to entrust the entire supply to whoever were the designated cooks for the week. Vinegar, as mentioned earlier, was not only a flavoring but more importantly, it helped prevent of scurvy.

Fruits and Vegetables

For soldiers in the field fresh vegetables were seldom issued since they were likely to spoil long before being consumed, or even delivered. At permanent stations they were more frequently available. For use in the field, there were desiccated vegetables, which were a concoction of miscellaneous greens, compressed into solid blocks and dried. They could be reconstituted with water or broth to be served as part of a meal or made into vegetable soup. Soldiers came to call desiccated vegetables “desecrated” .

Food sent from home

“Yesterday Wm Leydig and Bro got a Box with provissions from Home evry thing is very nice.”[9]

Many families sent care packages to friends and relatives in the army. Along with useful notions and clothing items, delicacies arrived. Canned foods, baked goods, sometimes even roasted poultry were sent to the soldiers. They weren’t too finicky in the field. There are accounts from soldiers saying that they received the box with its contents in good order, but the meat had rust (mold) on it. The recipient would have scraped the mold off, and then eaten it. The Adams Express Company provided delivery service to soldiers in the field and was reasonably fast in its deliveries so products shipped from home stood a half-decent chance of arriving in edible condition.

The Marching or Field ration

Of course, the army specified what and how much of it should be issued for each soldier’s consumption per day. The specifications looked like this:

Per Soldier:

Salt beef 12 oz

Soft Bread 20 oz, or

Hard Bread (hardtack) 16 oz or approximately 10 pieces And for every 100 rations:

Green coffee 10 pounds, or

Roasted & Ground 8 pounds

Sugar 15 pounds

Vinegar 4 quarts

Salt 60 oz

Pepper 4 oz

Molasses 1 quart

Soap and candles were included in the ration issue.

Civil War soldiers were quite resourceful in supplementing their diets. In friendly territory they’d buy from local farmers or storekeepers. Individual soldiers might pay cash for a dozen eggs or soft bread. A commissary sergeant could use government scrip or a receipt to purchase farm products in larger quantities. Soldiers might avail themselves of low hanging fruit as they marched past, without thought of paying for it. Bartering rations with citizens occurred. In enemy territory soldiers viewed everything as fair game and sometimes stripped a farm of everything they could find, including food preserved for the winter. Men would sometimes provide a voucher to a Confederate citizen with instructions to submit it to the War Department in Washington for reimbursement, knowing full well that the voucher would never get there.

Sutlers

Sutlers were private vendors licensed to travel with the army and provide items not regularly furnished by the government. Sutler inventories varied, but had to be approved by the army to ensure that soldiers could not buy prohibited items like whisky. Along with uniform buttons to replace those lost, hats and other items of clothing, and miscellaneous notions, they carried tinned foods, and fresh fruit which was quite a luxury. Sutlers were not always loved by the soldiers they served. If the men thought that a sutler overcharged or cheated them regularly, the men might organize midnight raids.

“Last night when all was calm and quiet a lot of Soldiers made a Rade on the Sutlers of the third Seventh Eight and Ninth Regts and stole from them nearly evry thing they had…” [10]

And of course, no one ever saw it happen.

Commutation of Rations

Under certain circumstances soldiers might have their rations commuted, that is, paid directly to them as cash advances. Men on detached duty away from their units or travelling on official government business where they could not reasonably expect to find a ration issue could purchase their own. Rations were commuted at the going rate for food at their home station. Soldiers on furlough, too, had rations commuted. Even though they were going home for a brief visit they were still in the army and the army was still responsible for feeding them.

Wild Game

Soldiers hunted but infrequently and hunting was seldom mentioned in contemporary accounts. When hundreds of men move into an area and start cutting down trees all game would run away. Besides, the army frowned on wasting ammunition. If the army found itself camped near a likely pond or stream the men would improvise some means of fishing to provide some variety to their diets.

Preparation and Cooking

By and large soldiers did their own cooking and there were no soldiers classified as cooks. In a permanent camp, a detail of soldiers was assigned the cooking duty. Kitchen furniture (kettles and mess pans) were generally provided by the army. Soldiers were expected to supplement the issued kitchen furniture with several large knives, dippers, large forks, colanders and so forth. The cooking duty was usually rotated now and again so that the same people weren’t stuck cooking forever. If the appointed cooks knew how to cook and keep everything clean, then there were good meals. If not, the food tasted awful and there was always the chance of sickness. Depending on circumstances, local directives permitted the employment of two or three African American assistant cooks.

In the field, soldiers would form small messes of three or four men who would share the meal preparation tasks among them: One to fetch water, another to gather firewood, one to cut or trim the rations and so forth.

Soldiers on the march provided themselves with mess furniture including cutlery, and plates. Sometimes the folks from the hometown would take up a collection among themselves to purchase cutlery and plates. Nesting utensils were available. Taking tableware from home, and more especially swiping it from Confederate households was much cheaper than buying it. Since infantrymen had to carry everything they owned on their backs, lightening their load assumed some importance. Oftentimes soldiers would limit their personal mess furniture to one folding knife, one spoon, one tin cup, and a multipurpose plate/pan/shovel which started life as a half of a water canteen. Throwing an old leaking canteen into the fire to melt the solder yielded two halves, and one half sufficed as a plate and frying pan when fitted with a stick for a handle.

Specifics

The Regulation sections spell out the authorized rations for troops. Some diary entries from the time would indicate that the regulation daily allowance was overly optimistic.

Following are the complete Subsistence Regulations, minus sample forms, from the US Army Regulations of 1861, as revised in 1863.

REGULATIONS

Subsistence Department. The Ration.

THE RATION.

1190. A ration is the established daily allowance of food for one person. For the United States army it is composed as follows: twelve ounces of pork or bacon, or, one pound and four ounces of salt or fresh beef; one pound and six ounces of soft bread or flour, or, one pound of hard bread, or,: one pound and four ounces of corn meal; and to every one hundred rations, fifteen pounds of beans or peas, and ten pounds of rice or hominy; ten pounds of green coffee, or, eight pounds of roasted (or roasted and ground) coffee, or, one pound and eight ounces of tea; fifteen pounds of sugar; four quarts of vinegar; one pound and four ounces of adamantine or star candles; four pounds of soap; three pounds and twelve ounces of salt; four ounces of pepper; thirty pounds of potatoes, when practicable and one quart of molasses. The Subsistence Department, as may be most convenient or least expensive to it, and according to the condition and amount of its supplies, shall determine whether soft bread or flour, and what other component parts of the ration, as equivalents, shall be issued.

1191. Desiccated compressed potatoes, or desiccated compressed mixed vegetables, at the rate of one ounce and a half of the former, and one ounce of the latter, to the ration, may be substituted for beans, peas, rice, hominy, or fresh potatoes.

1192. Sergeants and corporals of the Ordnance Department (heretofore classed as armorers, carriage-makers, and blacksmiths) are entitled, each, to one and a half rations per day; all other enlisted men, to one ration a day.

1193. Officers in charge of principal depots and purchasing stations will render to the Commissary-General monthly statements of the cost and quality of the ration, in all its parts, at their stations. The annexed table (pp.306, 307.) shows the quantity in bulk of each part of the ration, in any number of rations, from one to one hundred thousand.

ISSUES IN BULK.

1194. Stores longest on hand shall be issued first, whether the issue be in bulk or on ration returns. After the present insurrection shall cease, the ration shall be as provided by law and regulations on the first day of July, eighteen hundred and sixty-one." (Section 13, Act approved August 3, 1861.) Beans, peas, salt, and potatoes (fresh) shall be purchased, issued, and sold by weight, and the bushel of each shall be estimated at sixty pounds. Thus, 100 rations of beans or peas will be fifteen pounds, the equivalent of eight quarts; 100 rations of salt will be three pounds and twelve ounces, the equivalent of two quarts; and 100 rations of potatoes (fresh) will be thirty pounds, the equivalent of half a bushel.

1195. A Commissary required to send off subsistence supplies will turn them over to the Quartermaster for transportation, each package directed and its contents marked thereon. He will give the Quartermaster duplicate transportation invoices of the packages and their contents, as marked (Form 29), and take from him like receipts (Form 30). The Commissary who transfers the supplies shall also transmit duplicate invoices of them to the Commissary for whom they are intended, who shall return receipts for the supplies received (Form 32), and account as wastage on his next Return of Provisions for any ordinary loss of stores accruing in transportation.

1196. Any deficiency of supplies not attributable to ordinary loss in transportation, any damage, or discrepancy between the invoices and the actual quantity or description of supplies received, shall be investigated by a board of survey. (See paragraph 1019.) The officer revising the action of’ the board shall immediately transmit a copy of its proceedings to the Commissary-General of Subsistence, and a copy to the issuing Commissary. A copy of the proceedings of the board shall also accompany the receiving Commissary's Return of Provisions to the Commissary-General of Subsistence. Where the carrier is liable, the issuing Commissary shall report the amount of loss or damage to the Quartermaster authorized to pay the transportation account, in order that this amount may be recovered for the Subsistence Department.

1197. Invoices shall express the prices of articles named thereon.

ISSUES TO TROOPS.

1198. Subsistence shall be issued to troops on ration returns signed by their immediate commander, and approved by the commanding officer of the post or station. (Form 13.) These returns, ordinarily to be made for a few days at a time, shall, when practicable, be consolidated for the post or regiment (Form 14), and shall embrace only the strength of the command actually present. At the end of the calendar month, the Commissary shall enter on separate Abstracts, for each class of troops (see paragraph 1224), every return upon which he has issued provisions in that month; which Abstracts the commanding officer shall compare with the original ration returns, and if correct, so certify. (Form 2.)

1199. When men leave their company, the rations they have drawn and left with it shall be deducted from the next ration return for the company; a like rule, when men are discharged from hospital, shall govern the hospital return. When subsistence supplies are transferred from one Commissary to another, at the same post or station, they may be invoiced and receipted for according to Forms 31 and 32.

1200. Four women, as laundresses, are allowed to a company, and one ration per day to each when present with the company. In order that an authorized woman (laundress) of a company may draw rations while temporarily separated from it, the officer commanding the company must designate her by name and in writing to the commanding officer of the post or station where she may be living, as attached to his company, and entitled to rations. The rations of company women are not to be commuted, and they can only be drawn at a military post or station where subsistence is on hand for issue.

ISSUES TO CITIZENS.[11]

1201. One ration a day may be issued to each person employed with the army, when such are the terms of his engagement, on returns similar to Form 13. These returns will be entered on a separate Abstract (Form 3), compared, certified to, &c., as prescribed in paragraph 1198. No hired person shall draw more than one ration per day.

ISSUES TO INDIANS.

1202. When subsistence can be spared from the military supplies, the commanding officer is authorized to allow its issue, in small quantities, to Indians visiting military posts on the frontiers or in their respective nations. The return for this issue shall be signed by the Indian agent (when there is one present), and approved by the commanding officer of the post or station.

1203. Regular daily or periodical issues of subsistence to Indians, or issues of subsistence in bulk to Indian agents for the use of Indians, are forbidden.

ISSUES EXTRA.

1204. The issues authorized under this head shall be made on returns signed by the officer in charge of the guard, by the Assistant Adjutant General or Adjutant of the head-quarters, by the Quartermaster or other officer accountable for the animals, by the officer in charge of the working party, &c., as the case may be, and approved by the commanding officer of the post or station. At the end of the calendar month these returns shall be entered on an Abstract (Form 4), compared and certified to, as prescribed in paragraph 1198.

1205. Extra issues will be allowed as follows, viz.: ADAMANTINE CANDLES. To the principal guard of each camp or garrison, per month 12 pounds.[12] And when serving in the field, not exceeding the following rates per month, viz.:

To the head-quarters of a regiment or brigade..............10 pounds

To the head-quarters of a division................................ 20 pounds.

To the head-quarters of a corps.....................................30 pounds.

To the head-quarters of each separate army, when composed of more than one corps.......................................... ………………………40 pounds.

SALT. Two ounces a week to each public animal. The number of animals to be supplied, and the period drawn for, will be stated on each return for extra issues, and so entered on the Abstract. (Form 4.)

WHISKY. One gill per man daily, in cases of excessive fatigue, or severe exposure. The number of men issued to will be stated on each return for extra issues, and so entered on the Abstract. (Form 4.) Under "Remarks," on the return and on the Abstract, the letters of companies to which the men belong; number and designation of regiment, &c., will be given.

1206. Oil, candles, or gas, with which to light a fort, barrack, or stable, are not allowed from the Subsistence Department. Extra issues of subsistence, except as prescribed in preceding paragraph, are forbidden. (See Notes, page 265.)

ISSUES TO HOSPITAL.

1207. Subsistence shall be issued to a hospital on ration returns signed by the medical officer in charge, and approved by the commanding officer of the post or station. These returns (Form 13) will be made for a few days at a time. .

1208. Medical cadets and female nurses employed in permanent or general hospitals are entitled, each, to one ration per day, either in kind, or by commutation at the cost of the ration at their station.

1209. The Abstract of issues to a hospital shall be made by the Commissary, and certified to by the Surgeon and the commanding officer. (Form 5.) The Surgeon's certificate to this Abstract shall include the provisions issued to hospital from the subsistence storehouse, and the amount of purchases for it in the month. Medical officers will not be allowed to sell or exchange any portion of the ration saved in hospital.

Conclusion

It is clear from the text of the regulations that the government was extremely thrifty in issuing supplies of every kind and made great efforts to prevent fraud.

Given the circumstances and the need for expediency in raising, supplying, and feeding a very large army in a short period of time, the government did well in working through the myriad of obstacles. Federal soldiers may have gone hungry from time to time, yet no one starved.

- [1] Captain James M. Sanderson, Camp Fires and Camp Cooking; or Culinary hints for the Soldier: Including Receipt for Making Bread in the “Portable Field Oven” Furnished by the Subsistence Department (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1862), 2

- [2] Barbara M. Croner, ed., A Sergeant’s Story: Civil War Diary of Jacob J. Zorn 1862-1865 (Apollo, PA: Closson Press, 1999); Citations are quoted exactly as they appear with no corrections of spelling or grammar.

- [3] David Herbert Donald, ed., Gone for a Soldier: The Civil War Memoirs of Private Alfred Bellard (Boston, MA: Little brown and Company, 1975), 118-22; Note raisins could be purchased from a sutler.

- [4] Croner, Sergeant’s Story, 37.

- [5] Ibid., 48.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Donald, Gone for a Soldier, 119.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] Croner, Sergeant’s Story, 49.

- [10] Croner, Sergeant’s Story, 48,

- [11] The modern term civilian had not yet come into common use.

- [12] Adamantine candles were made commercially from animal fat that was processed mechanically and using chemicals.

If you can read only one book:

Croner, Barbara M., ed. A Sergeant’s Story: Civil War Diary of Jacob J. Zorn 1862-1865. Apollo, PA: Closson Press, 1999.

AND

Donald, David Herbert, ed. Gone for a Soldier: The Civil War Memoirs of Private Alfred Bellard. Boston, MA: Little brown and Company, 1975).

Books:

Billings, John D. Hardtack and Coffee or The Unwritten Story of Army Life. Boston, MA: George M Smith & Co, 1888.

Horsford, E. N. The Army Ration. How to Diminish its Weight and Bulk, Secure Economy in its Administration, Avoid Waste, and Increase the Comfort, Efficiency, and Mobility of troops. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1864.

Kautz, August V. Customs of Service for Non-commissioned Officers and Soldiers as Derived from Law and Regulations and Practiced in the Army of the United States. Philadelphia, PA : J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1864.

Sanderson, Captain James M. Camp Fires and Camp Cooking; or Culinary hints for the Soldier: Including Receipt for Making Bread in the “Portable Field Oven” Furnished by the Subsistence Department. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1862.

Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861. With an Appendix Containing the Changes and Laws Affecting Army Regulations and Articles of War to June 25th, 1863. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1863.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.