The Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski

by Herbert M. Schiller

Fort Pulaski | Savannah Georgia | Confederate Blockade Runners | Colonel Charles H. Olmstead | General Quincy A. Gillmore | General David Hunter

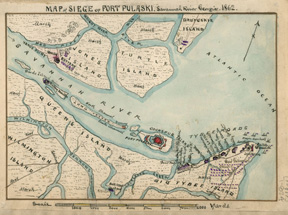

Arising on the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains, the Savannah River flows east and forms the boundary between Georgia and South Carolina. Twelve miles from the coast it passes the city of Savannah, and continues to the sea, there cut on both sides by numerous channels between the coastal barrier islands. These islands, many of them tidal, are covered by marsh grass and from a distance have the appearance of a savannah. Close to the ocean is a deposit of mud, Cockspur Island, dividing the river into two channels. There sits Fort Pulaski, built to control the passage of ships and to resist attacks on Savannah.

Savannah was a major international port of the antebellum South. It was a large cotton center, and her shipbuilding, associated marine businesses, and railroad shops, were her primary military industries. Three railroads converged on the city, two of which heading north and south are roughly parallel to the sequence of coastal barrier islands.

Cockspur Island had been the site of a pre-Revolutionary War stockade, as well as a second built in the 1790’s, but destroyed by hurricane in 1804. Subsequent to the War of 1812, a series of masonry forts was planned and constructed along the American eastern and gulf coasts. Cockspur Island was again chosen as the site in the early 1820’s, but work did not begin until 1829. The original plans called for a structure identical to Fort Sumter, i.e., a two-story pentagonal fort with three tiers of guns. Engineers determined that Cockspur’s muddy soil would not support such a weight of masonry, so the plans were modified to a single story with one row of casemate guns, and above a row of parapet (barbette) guns.

Construction was initially supervised by Major Samuel Babcock. In the autumn of 1829 Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, newly graduated from the United States Military Academy, arrived to serve as Babcock’s assistant. The young engineer lieutenant located the site for the fort, and supervised the construction of the drainage canals and dikes. Assigned to Virginia in 1831, Lee would not visit the fort again until early in the Civil War. In 1833 the fort was named for Count Casimir Pulaski, who had been mortally wounded in 1779 during the battle of Savannah. Malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and dysentery halted construction each summer. In 1847 the fort was completed, largely under the direction of Lieutenant Joseph King Fenno Mansfield.

Fort Pulaski was thought to be impregnable, as were all the of masonry forts which protected the eastern and gulf coasts. It was inaccessible to ground offensive and was believed to be too far away from possible enemy battery sites. Prior to the Civil War, the chief engineer of the United States Army had said, “You might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains as Fort Pulaski. . . . The fort could not be reduced in a month’s firing with any number of guns of manageable caliber.”[1] The siege which would occur in 1862, using the newly developed rifled artillery, would immediately render the network of masonry forts obsolete.

The pentagonal fort had two faces to guard the south channel of the river, the south and southeastern faces; two faces to guard the North Channel, and the gorge; the least vulnerable side, facing west toward Savannah. At the three ocean-facing angles of the fort there was constructed a short face, a pancoupé, at the angle of the walls. Each pancoupé has a single casement and embrasure (opening) for a gun to protect the potential blind spot at the angle. Twenty 32-pounder naval guns were installed in 1840; no further guns were added until after the fort was seized by Georgia authorities in 1861. The fort’s brick walls are seven and a half feet thick and rise twenty-five feet above the water line. The gorge was protected by a demilune and the entire structure was surrounded by a moat, up to forty-eight feet wide.

Shortly after South Carolina passed her Ordinance of Secession on December 20, 1860, Georgia’s Governor Joseph Emerson Brown met with Colonel Alexander Robert Lawton, commander of the 1st Volunteer Regiment of Georgia. They elected to occupy Fort Pulaski before Federal forces could take the fort and close the river. On a rainy January 4, 1861, infantrymen and artillerymen, accompanied by six small artillery pieces, boarded the side-wheel steamer Ida and descended to the north wharf of Cockspur Island, disembarked, and marched to the fort. The caretaker ordnance sergeant immediately surrendered the fort, its rusting guns, and its small supply of powder and ammunition. Twelve days later Georgia voted to secede from the Union.

The neglected fort had unlivable quarters, an overgrown parade, and a silt-clogged moat filled with marsh grass. One hundred and twenty-five slaves labored for months to restore the fort to habitable conditions. During the first half of 1861, the 1st Regiment of Georgia Volunteers, along with other state troops, continued to work on the fort, and also prepared defenses on the barrier islands both south and north of the Savannah River.

In October 1861 Major Charles Hart Olmstead took command of Fort Pulaski; he would shortly be promoted to colonel. A native of Savannah, he had been educated in the Georgia Military Academy, and was a local businessman as well as regimental adjutant when Georgia seceded. During 1861 and early 1862, thousands of pounds of gunpowder and ammunition were brought to the fort. Olmstead was able to boost his artillery complement to 48 guns, including 12-inch mortars, two English Blakely rifles, and 10-inch columbiads. The Ida continued to visit the fort daily, and other steamers towed barges filled with lumber, arms, gunpowder, and food as needed.

On May 27, 1861, the first Federal blockading vessel arrived at the mouth of the Savannah River. Although the port was now “closed” a few more blockade runners were able to dash in during subsequent months. After additional vessels joined the blockade, Confederates erected a sand fort near the lighthouse on northeast Tybee Island, which is located across the south channel southeast of Cockspur Island. The rebel fort kept the blockading vessels at a distance and discouraged landings by Federal forces.

On November 7, 1861, General Robert E. Lee arrived to command the newly consolidated Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and East Florida. Lee abandoned Hilton Head Island that same day, after the Federal took Port Royal Sound, and ordered the withdrawal from other exposed Georgia coastal island defenses and shipped their artillery to Savannah. His plan was to patrol with cavalry and use the coastal railroads to move infantry and artillery in a timely basis to repel potential invaders.

The Federal occupation of Port Royal Sound and Hilton Head Island was an integral part of the Federal blockading plan. Hilton Head, along with Fernandina, Florida, were both seized by Federal forces for use as coaling stations by the blockading fleets. The combined operations were directed by Brigadier General Thomas West Sherman and Commodore Samuel Francis DuPont. Among Sherman’s staff officers were chief engineer Captain Quincy Adams Gillmore, ordnance officer Lieutenant Horace Porter, and chief topographical engineer Lieutenant James Harrison Wilson. These three men would have full careers in the subsequent four years.

Sherman quickly occupied the adjacent South Carolina coastal islands. The day after Hilton Head Island was abandoned, the Confederates evacuated their sand fort on Tybee Island. Later that same month Federal forces landed on Tybee, and on November 25, General Sherman and Captain Gillmore inspected Fort Pulaski through telescopes and agreed that they could reduce the fort by a combination of mortars and breeching guns. Within a week, Gillmore ordered sixteen mortars, ten heavy rifled guns, and ten columbiads.

Conventional military doctrine called for plunging mortar fire to penetrate and disrupt the parapet and shattering the underlying casemate arches, while the smooth bore guns slowly pounded the thick wall into brick fragments and dust. Rifled guns were new and a few experiments using them against masonry walls had been reported, primarily in Britain, and Gillmore was aware of these reports. Rifled guns were more effective than smooth bore guns of comparable caliber, when fired from distances of a mile or more. Although General Sherman had little confidence in the rifled guns, he allowed Gillmore to use them in his bombardment.

In early December, Colonel Rudolph Rosa’s 46th New York occupied Tybee Island, and was soon joined by two companies of the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, which mounted guns in the abandoned Confederate sand fort. Colonel Alfred Howe Terry’s 7th Connecticut arrived on Tybee later that month.

Meanwhile, General Lee persevered in strengthening the inner coastal defenses of his department. Accompanied by Governor Brown, Brigadier General Lawton, and a dozen other officers, Lee visited Fort Pulaski on November 10-11. He told Colonel Olmstead “They will make it very warm for you with shells from that point [on Tybee Island] but they cannot breach at that distance.”[2] The greatest distance balls could be effective against masonry wall was 800 yards and Tybee was over 1,700 yards away. Lee was apparently unaware of the experiments with the new rifled guns. During the visit Lee advised Olmstead to place sand bag traverses between the parapet guns to protect the gunners from bursting shells, to dig ditches in the parade to catch rolling shells, and to tear down any wooden structures along the officers’ quarters. Lee further told Olmstead to erect blindages around the interior of the fort and to cover them with several feet of earth.[3] Many barges full of heavy beams subsequently came down from Savannah and were floated up the irrigation ditch from the south channel into the moat. By the time the fort was isolated in February, Olmsted had 45 guns in the fort and three mortars in batteries outside the fort.

General Sherman now directed Captain Gillmore to explore the possibility of erecting a battery on Jones Island, approximately three and a half miles up the Savannah River from Fort Pulaski on the South Carolina side of the river. Gillmore located an area of dry ground on the Savannah River side of the island, approximately one mile from the closest wharf site on the north shore. Gillmore described Jones Island: “The substratum being a semi-fluid mud, which is agitated like jelly by the falling of even small bodies upon it, like the jumping of men, or the ramming of earth. . . .Men walking over it are partially sustained by the roots of the reeds and grass and sink in only five or six inches. When this top support gives way or is broken through they go down two or two and one-half feet and in some places much farther.”[4]

During early February 1862 soldiers on Daufuskie Island, a coastal island south of Hilton Head Island, cut 10,000 pine trees and rafts of trees, along with filled sandbags, were brought to Jones Island. The wharf was completed on February 8 and two days later a corduroy pathway crossed the island and the sandbags were laid for the battery platform. During the next two nights, during a driving rain storm, teams of 35 men began moving the six cannon, two guns at a time, to the battery. First, three pairs of planks, fifteen feet long, one foot wide, and three inches thick were laid end to end. The first gun was rolled to the end of the first pair; the second gun was rolled to the end of the second pair; and the third pair was then moved to the front of the first gun and the process repeated again and again. The men sunk to the knees at every step. Soon the planks were so slippery that they had to be moved with ropes. Work was halted during the day and resumed on the second night. Guns would frequently slip off the planks and immediately sink to their axles. The men would carefully lever them back onto the track and begin anew. Despite all the hardships, six guns were on the platform before sunrise on February 12. Named Battery Vulcan, it was a mere eight inches above high tide.

The following day the unsuspecting Ida chugged down the river towards the fort. The six guns open on the steamer; five immediately recoiled into the ooze. Unharmed, the Ida reached the fort, concluded her business, and returned to Savannah by Lazaretto Creek off the south channel of the river. The battery platform was enlarged and the muddy guns retrieved and cleaned.

On February 20 Union forces erected six-gun Battery Hamilton on the much smaller Bird Island, which lay in the Savannah River directly across from Battery Vulcan. The Savannah River was now closed to boat traffic. Two days later, the Federals sank an armed hulk in Lazaretto Creek, thus closing that passage to and from Savannah to the fort. Except for an occasional courier delivering newspapers, the fort was now cut off from Savannah.

As early as December, 1861 General Sherman had begun his efforts to have Captain Gillmore promoted to Brigadier General, a rank Sherman felt more suitable to the engineer operations Gillmore was about to direct. After much correspondence, and temporary denials, in February 1862 Gillmore received the promotion to acting Brigadier General.

General Gillmore now began preparation of his siege batteries on the northwestern shore of Tybee Island. Here there were several areas of sandy higher ground. The distance from the northeast landing site of Tybee Island to the future battery sites was two and a half miles. The last mile was low and marshy could only be crossed by a road corduroyed with brushwood and bundles of sticks and in full view of the fort. By late February Tybee Island garrison included the 46th New York, the 7th Connecticut, two companies of the 1st New York Volunteer Engineers, five companies of the 8th Maine, two companies of the 3rd Rhode Island Artillery, and a few members of Lieutenant Wilson’s company of engineers.

General Gillmore would direct all of the preparation for the bombardment of Fort Pulaski. On February 21 the first piece of heavy artillery arrived, and over the next seven weeks a total of thirty-six guns would arrive—twelve 13-inch mortars, four 10-inch mortars, six 10-inch columbiads, four 8-inch columbiads, five James rifles of varying calibers, and five 30-pounder Parrott guns. The James rifles and the Parrott guns were both rifled muzzle loaders, and innovative projectiles “took” the rifling when fired, providing greater accuracy and greater penetrating power than balls from smooth bore gun.

The tube of a 13-inch mortar weighed 17,000 pounds; the tube of a 10-inch columbiads weighed 15,000 pounds. Wharf facilities for unloading cannon tubes and carriages did not exist on Tybee Island, and so each individual tube or gun carriage was loaded into a lighter on which a platform had been prepared by laying thick planks across the gunwales. The heavy surf of the Atlantic beach of Tybee was a problem. At high tide, soldiers ashore pulled the lighter towards the shore with ropes. When the lighter was close as possible, up to fifty men would tip it and roll the gun tube into the water. At low tide, up to 250 men would pull ropes fastened to the tube or carriage and drag it above the high tide line, a labor that could take more than two hours.

Infantrymen would prepare sling carts, two pairs of giant wheels attached by two heavy beams, braced together by three cross pieces. Either the gun or carriage would be pulled up to the beams, or the gun or carriage attached to the beams first and they then attached to the axle assembly. Teams of up to 250 men would then pull the carts in the darkness. Commands were conveyed by whistles; the men could only whisper. The last mile was over boggy ground and the wheels would sometimes slip into the mud and sink five feet to their hubs.

Altogether eleven battery sites would be built on the northwest shore of Tybee Island. Construction of gun platforms, magazines, shelters, and the mounting of the guns was performed at night, frequently in the rain, so as to be invisible to the defenders in the fort. Once a camouflaged parapet was complete, work could continue behind it with more freedom. All work was covered with brush before dawn. Slowly, over seven weeks the soldiers completed the batteries, unloaded the powder, shot, and shells, which were stored near the lighthouse and in the magazines sited near the batteries.

Confederates grew suspicious of Federal activities, and on the night of March 22 three rebels slipped across the south channel and discovered a Federal battery. They reported to Colonel Olmstead who immediately ordered the fort to fire on the western end of the island. At dawn he could not see that any damage had been done; he was correct indeed, but now the Confederates knew of the batteries’ existence. In addition, two days earlier a group of men from the 46th New York, on a reconnaissance west of Tybee Island, were captured and also confirmed the presence of the batteries, which was conveyed to Colonel Olmstead on April 4.

On March 31 Major General David Hunter arrived to replace Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman as commander of the Department of the South. Although Sherman had secured Port Royal Sound and occupied the surrounding South Carolina islands, Tybee Island, and Fernandina, Florida, there had been little seeming progress with the developing siege activities on Tybee Islands, and many felt that Sherman had not shown a sufficiently aggressive spirit. Hunter, a United States Military Academy graduate, was a noted abolitionist, and a friend of President Abraham Lincoln. In addition, Hunter brought with him Brigadier General Henry Washington. Benham to oversee the northern portion Hunter’s Department. Benham, an engineer officer, immediately toured the Federal batteries with Gillmore and encouraged their speedy completion.

Beginning in April the Federal infantrymen began intensive drills on their guns. Instructed by the Rhode Island artillerymen, they practiced everything but firing. Some were concerned that the Union gunners did not have the opportunity to get the range of their pieces before the bombardment began. In addition, others were concerned about rumors of an ironclad being constructed in Savannah which could pass Batteries Vulcan and Hamilton and jeopardize their efforts. The eleven Federal batteries, their armament, and distance to Fort Pulaski, are listed below:

Nine hundred shot or shells for each gun were stored in service magazines, along with sufficient powder for two days firing. An additional 3,600 barrels of gunpowder were stored near the lighthouse on Tybee Island. On the night of April 9 General Gillmore issues his final orders. The mortar batteries were to drop their shells on the parapet above the casemates to penetrate the earth and collapse the underlying arches. Columbiads in Batteries Lyon and Lincoln were to fire over the southeast wall and hit the interior of the gorge and north faces. Batteries Scott, Sigel, and McClellan, after silencing the barbette guns, were to fire on the pancoupé between the south and southeast wall, and then the adjacent casemate on the southeast wall.

At dawn on April 10 Confederates discovered that all the brush had been removed along the north of Tybee Island, revealing the Federal batteries. Only part of Pulaski’s artillery—ten barbette guns, six casemate guns, and two mortars—could fire on Tybee. Only four barbette guns and three casemate guns could fire on the site of the eastern most Federal batteries, housing the rifled guns. Confederates now spotted a small boat rowed by four sailors, with a Union officer holding a white flag, coming toward the south wharf of Cockspur Island. Lieutenant Wilson delivered General Hunter’s demand for the fort’s surrender, along with his instructions to await an answer no longer than thirty minutes. With the Federal batteries unmasked, Olmstead knew the moment he had anticipated had now arrived. He used his thirty minutes to assemble his men, post them to their guns, serve ammunition, and prepare the hospital. After exactly thirty minutes he sent his reply: “I am here to defend the fort, not to surrender it.”[5] When Hunter received the reply, he ordered the batteries to open at 8:15 a.m.

The initial fire of both sides was slow and wild, as each side learned the range of their targets. Within an hour, the Federal batteries were each firing three rounds a minute; the northwest shore of Tybee Island was a bank of smoke punctuated by blasts of flame. Colonel Rosa and members of the 46th New York manned the guns of Battery Sigel. Rosa disregarded his instructions, mounted the parapet, and ordered his men to fire all six guns in volleys. Volley after inaccurate volley, accompanied by great cheering, led Gillmore to send Rosa away. When the New Yorkers refused to work without their colonel, Gillmore replaced them with trained naval artillerists from the Wabash, then off shore.

Shortly before noon, the halyard of Pulaski’s flagpole was cut and the rebel flag fluttered down. Thinking Pulaski had surrendered; the Federals mounted their parapets and cheered their victory. The Confederates soon retrieved their flag and mounted it on a cannon rammer. Federal firing resumed.

Inside the fort, an early shot came through a casemate opening and dismounted a gun. The James projectiles were fracturing the bricks. Olmstead wrote “Thirteen inch mortar shells, columbiad shells, Parrott shells, and rifle shots were shrieking through the air in every direction, while the ear was deafened by the tremendous explosions that followed each other without cessation.”[6] After three hours three casemate guns were dismounted; by the end of the first day most of the guns on the sea face of the parapet had been dismounted. Late on the afternoon of the first day, Olmstead was in a casemate when a columbiads shot struck the still intact fort wall. The colonel observed that it “bulged the bricks on the inside, a significant fact that left little doubt of what the ultimate result would be.”[7] By the end of the day, all but two feet of the wall’s thickness had been blown away.

During the night of the first day’s bombardment, Olmstead inspected the exterior of the fort. “It was worse than disheartening, the pancoupé at the south-east angle was entirely breached while above, on the rampart, the parapet had been shot away and an 8-inch gun, the muzzle of which was gone, hung trembling over the verge. The two adjacent casemates were rapidly approaching the same ruined condition; masses of broken masonry filled the moat.”[8]

Slow Federal fire continued throughout the night, and resumed again in earnest with the morning light of April 11. Shells from the rifled guns fractured ever deeper into the brick wall, and columbiads balls sent cascades of rubble into the moat as an orange-brown cloud of brick dust rose over the fort. By noon three casemate arches were clearly open. Gillmore ordered the guns to concentrate on the next, adjacent casemate. It was now apparent that the face of the southeast wall would be peeled off. With the moat filled with rubble, General Benham ordered his aide, Major Charles Graham Halpine, to prepare an assault party to enter the fort on the April 12; it would prove unnecessary.

By mid-day inside the fort all was wreckage. Seven barbette guns were dismounted; the west side of the wall was a wreck. At 1:00 p.m. a shell entered an opened casemate, passed across the parade, and through the top of a traverse to explode in the magazine in the northwest corner of the fort. The magazine, containing twenty tons of powder, filled with a flash of light and smoke, but did not explode. Olmstead knew the next such round could explode the entire fort and kill the entire garrison. He realized nothing was to be gained by further resistance; at 2:00 p.m. Confederate fire ceased and a white flag was raised. Incredibly, only three Confederates had been seriously wounded.

A violent storm had blown up on April 11; Benham and his staff searched in vain for a boat to row across to Pulaski. Gillmore slipped away, found some Wabash sailors, who understood tides and currents and who had a boat, and had them row him across to the fort. He quickly entered the fort, had the gates shut, and met with Olmstead for an hour arranging terms of surrender. When the Federal party, led by Halpine, arrived Gillmore kept them waiting outside until he had the signed surrender document. Gillmore then admitted Halpine’s party to take charge of the surrender of the 385-man garrison, and receive the flag and officer’s swords. Gillmore left to present the surrender to General Hunter. Lieutenant Porter wrote his sister, mindful of events of a year before, that “Sumter is avenged!”[9]

The 7th Connecticut and 1st New York Volunteer Engineers began repairing the breech and by the end of May it had been completed; their work is obvious today. The guns were removed from Tybee Island and shipped northward, some destined for the siege of Fort Sumter. Batteries Vulcan and Hamilton in the Savannah River were disarmed. In June the 48th New York replaced the 7th Connecticut as the garrison; in 1863 the garrison was reduced.

The Federals had fired over five thousand projectiles; the Confederates, a third as many. Gillmore observed that the largest James projectiles had penetrated up to twenty-six inches. Most of the damage was caused by the James rifles. The Parrott rounds penetrated up to eighteen inches. The columbiads had less penetrating power but were most effective crushing out immense masses of masonry. Fewer than 10% of the mortar rounds had hit the fort. The mortars caused none of the anticipated damage to the casemate arches. As effective as was the Federal artillery, it would have been even more so had the crews been given the opportunity to drill and fire their guns before the actual bombardment.

The effectiveness of rifled artillery meant that future sieges and bombardments could be prepared for more easily. Instead of seven weeks of heavy labor preparing batteries and moving heavy mortars and columbiads, lighter rifled guns could be more quickly maneuvered into position. Rifled guns would play a major role in Gillmore’s next endeavor—the siege and bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor.

The use of rifled artillery revolutionized siege warfare. Before the reduction of Fort Pulaski, masonry forts were regarded as impregnable. Major General David Hunter best summarized the significance of what happened on Cockspur Island:

The result of this bombardment must cause, I am convinced, a change in the construction of fortifications as radical as that foreshadowed in naval architecture by the conflict between the Monitor and Merrimac. No works of stone or brick can resist the impact of rifled artillery of heavy caliber.[10]

- [1] Peggy Robbins, “Storm Over Fort Pulaski,” America’s Civil War, 3 (September, 1990): 30; Roger S. Durham, “Savannah [:] Mr. Lincoln’s Christmas Present,” Blue & Gray, 9 (February 1991): 12.

- [2] Robert E. Lee to Charles H. Olmstead, November 21, 1861, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina; Charles H. Olmstead, “Fort Pulaski,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, 1, no. 2 (1917): 102; Charles H. Olmstead, Memoirs of Charles H. Olmstead (Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, 1964), 90-91.

- [3] The blindage was a protective screen formed by leaning large beams against the inner wall to protect the casemate openings from shells exploding within the interior of the fort.

- [4] Quincy A. Gillmore, Official Report to the United States Engineer Department of the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, February, March, and April 1862, (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862), 14.

- [5] New York Times, April 19, 1862.

- [6] Charles H. Olmstead to Florence (Williams) Olmstead, April 11, 1862, Fort Pulaski National Monument Collection.

- [7] Olmstead, “Fort Pulaski,” 103-4.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] Horace Porter to his sister, April 11, 1862, Library of Congress.

- [10] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 14, p. 134.

If you can read only one book:

Schiller, Herbert M. Sumter is Avenged: The Siege & Reduction of Fort Pulaski. Shippensburg, PA: The White Mane Publishing Company, 1995.

Books:

Gillmore, Quincy A. Official Report to the United States Engineer Department of the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862.

———. “Siege and Capture of Fort Pulaski,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 2. New York: The Century Co, 1884, 1-12.

Olmstead, Charles H. “Fort Pulaski,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 1 (1917): 98-108.

Olmstead, Charles H. and Lilla Hawes, eds. “The Memoirs of Charles H. Olmstead” Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, 1964.

Schiller, Herbert M. Fort Pulaski and the Defense of Savannah. n.p.: Eastern Acorn Press, 1997, 1-27.

United States War Department. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 6, p. 133-67.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This is an online full text version of Quincy A. Gillmore: Official Report to the United States Engineer Department, of the Siege and Reduction of Fort Pulaski. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862, provided by the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

This website by Quantum Tour provides a virtual tour of Fort Pulaski.

This is the National Park Service Fort Pulaski National Monument Administrative History providing a comprehensive account of the development of the national monument.

This is an online full text version of “Coast Defense in the Civil War. Fort Pulaski, Georgia” in Journal of The United States Artillery Fort Monroe, VIRGINIA: School Board of the Coast Artillery School, 1913, 40: 205-15, provided by the Hathi Trust Digital Library.

This is a collection of on line images of Fort Pulaski from a Google search.

This is the Wikipedia entry for the Fort Pulaski National Monument.

Other Sources:

National Park Service Fort Pulaski National Monument

The Fort Pulaski National Monument is located at U.S. Highway 80 East, Savannah GA 31410-0757, and telephone 912 786 5787. The monument is open every day except Christmas from 8:30 a.m.-5:15 p.m. and house may be extended during the summer.