Fort Sumter

by David Detzer

The opening shot of the Civil War was fired on Fort Sumter, 4:30 a.m. April 12, 1861.

All countries have weak geographic spots which enemies might exploit, mountain passes, perhaps, or shallow river crossings. Countries with long coastlines are especially uneasy, and remain on the lookout for enemy armadas or even pirate fleets.

The United States is lucky. Although its coastlines, compared to other countries, are immense, the vastness of the Atlantic and Pacific obviously offers certain security. But prudence has always fostered cautiousness. When Dutch settlers arrived at what is now the southern tip of Manhattan, they placed cannon in the area that became known as The Battery. And the founders of the Jamestown settlement found a place near them that could be used to protect their flank. Here they erected what they called Fort Algernourne. Their tiny bastion, at the entrance of Chesapeake Bay, eventually transmogrified to become the major American fortress, Fort Monroe, which protected, among other things, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and the District of Columbia.

By 1860 the United States had scores of fortifications along the coastline stretching from Maine to Texas. For example, several defensive structures protected Boston, and Fort Pickens at Pensacola was designed to defend much of the Gulf Coast.

But the nation’s army was far too small to man all these forts properly. Fort Monroe, the largest, had only a couple of hundred soldiers manning its extensive walls. Other fortifications sat entirely empty.

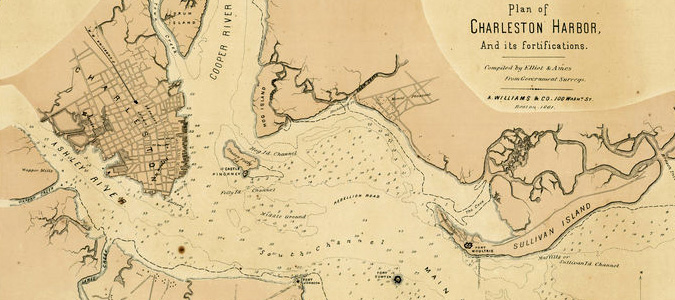

Charleston, South Carolina was one of the nation’s most important ports. The city, hidden deep within its own harbor, sat on a narrow peninsula created by two rivers, Ashley and Cooper, which flowed down from the interior of the state. Ever since the American Revolution, when colonial militiamen constructed a barricade of logs on Sullivan’s Island to protect the city from British attackers, America had kept a fortification, eventually called Fort Moultrie, in that spot on Sullivan’s Island that lay on the northern side of the harbor. By the late 1850s this fortress housed inside its walls about seventy soldiers, some of whose wives and children stayed near them. This garrison lived a fairly isolated life here, though there was constant interaction with local civilians. A few wives had relatives in town. Also the fort drew provisions from city merchants. During summer months, heat and humidity pressed some of Charleston’s citizenry to purchase or rent cottages on Sullivan’s Island, and, thus, Fort Moultrie was surrounded by civilian homes. The fort, and its little military band, offered dances every year, which civilian South Carolinians happily attended. There were the usual human interactions between soldiers and locals: squabbles, flirtations, fist fights, children’s games. All in all the soldiers of Fort Moultrie had no notion that their little place was about to become the center of American politics.

In Washington, D.C., General Winfield Scott, the head of the American army, ruminated about South Carolina. At seventy-four years old, he was elderly for his position, but he was America’s most experienced and most-respected soldier and still retained a keen mind and a canny understanding of the nation’s politics, to say nothing of an acute awareness of his army’s weaknesses. He heard about rumblings from Charleston, and contemplated the ineffective officer in command of Fort Moultrie, Lieutenant Colonel John Lane Gardner.

The nation’s voters elected Abraham Lincoln on November 6, 1860. During the following week General Scott came to a decision. He told Colonel Gardner to step aside, and ordered Major Robert Anderson to travel immediately to Charleston and take command of Moultrie. Scott’s choice turned out to be brilliant.

Major Anderson proved himself a person of depth and character. Although about to be the central character in one of the great dramas in American history, he had been, outside of army circles, totally obscure until that moment. Fifty-five-years-old, he had studied the use of cannon since his cadet days at West Point, then taught the subject at his alma mater, and used his knowledge well during the Mexican War where he served with great distinction. During his long military career he had served in various posts, including even Fort Moultrie. He was a fine-looking man, clean-shaven, with dark eyes, set in tan, leathery cheeks. Slightly above average height, he was muscular and stood ramrod-erect. But by 1860 he was beginning to feel his age, and was pondering retirement.

Robert Anderson’s attitudes about “the South” were about to be endlessly analyzed—in South Carolina, in Washington, and in countless drawing rooms throughout America. Abraham Lincoln himself often wondered aloud about Anderson’s loyalties. During the next six months newspaper readers would be informed that he had been born in Kentucky (a slave state). He had married a well-to-do Georgia belle named Eba, who inherited some of her father’s many slaves, thereby making Anderson himself part-owner of more than a dozen individuals. But Robert and Eba Anderson had settled in New York City, and at some point they had, apparently, sold those slaves. He was, however, certainly no fervent abolitionist, nor was he in any obvious way antagonistic toward the South. During his military career he had become quite close to General Scott, and he also knew Robert E. Lee rather well and was a friend of Jefferson Davis, a fellow graduate of the Military Academy (and a man who had eventually become Secretary of War, and was now, in 1860, a senator from Mississippi). At West Point Major Anderson had taught artillery lessons to many Southern cadets, including Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. Despite his Southern connections, Anderson firmly opposed the notion of “secession,” on principle. He was a reserved man, not given to emotional commentary, but he was about to prove himself to be a patriotic American who loved his country—his whole country. Therein lay the foundation of what was about to happen.

Even before his arrival at Fort Moultrie, he was well aware that Charleston Harbor had several military facilities, including Fort Moultrie, small Castle Pinckney, near the city, and Fort Sumter, an empty bastion sitting atop an island somewhat close to the mouth of the Harbor. Sumter was small, having a footprint of only two-and-a-half acres (compared to Fort Monroe’s 565 acres). On the other hand, Sumter was designed to accommodate 650 men and 135 cannon. The army had started constructing it in 1829, shipping down countless loads of granite from New England to form its base, then unhurriedly erecting the basically pentagonal brick fort. Over the years, masons and bricklayers did complete its five-foot-thick, three-tiered walls, and its two large barracks and a three-story central building designed to house officers and provide storage. Inside its walls lay an open space called the parade, a charmless area, much like a prison yard, generally in deep shadows because of the high walls on all sides. By 1860 Sumter remained unfinished, though it housed many of its cannon.

Its original purpose was to protect Charleston from outside assaults. The designers, however, recognized that attackers might succeed in capturing and entrenching one or more of the islands around the Harbor. Hence the fort’s main five sides. It is revealing that the designers and engineers always referred to the fort’s northern side as “left” and the southern side as “right.” In their minds, Fort Sumter faced out to sea. Its entry, a large gateway, was on the side facing the city for two reasons. Attackers would hardly capture Charleston and fire at Sumter. Besides, virtually no artillery in 1829 had the range to reach from the city to the fort.

In November 1860 the fort was uninhabited. Except when sea winds echoed through its emptiness or storm-tossed waves spumed and crashed against its granite base, the fort sat silent and still, seemingly far away from the outside world. South Carolina’s politicians, however, were well-aware of its proximity to the city, and many of them intended to do something about it, in due time.

But the first matter on the state’s political agenda was secession. The notion of withdrawing from the Union if connections with the United States proved unacceptable, had long been a given in South Carolina. Only a few irascible locals debated the matter, and their nattering was ignored. In fact, by the late 1850s most of the state’s leadership felt that ties with the Union were already snapping. The rise of the Republican Party, since its creation in 1854, seemed especially unsavory due to the rhetoric of its anti-slavery wing. In the summer of 1860, when Abraham Lincoln, who most South Carolinians mistakenly considered a rabid abolitionist, was nominated, secession was openly discussed on the streets and in the salons of Charleston. The city’s leaders were so accustomed to thinking secession a perfectly natural right, they assumed that declaring their independence would be an easy, natural, and bloodless event. And quite satisfying.

Francis Wilkinson Pickens was governor of the state. A man of wealth, with many family connections to the state’s history, Governor Pickens had won his position because of those connections, not his charm. He was squat and shapeless in body; his deep-seated eyes within his potato-shaped head offered neither geniality nor warmth. He himself admitted, “I believe it is my destiny to be disliked by all who know me well.” Traditionally, governors of this state held little power, but Francis Pickens happened, by chance, to be during the next few months, one of the most important governors in American history.[1]

After Lincoln’s election, South Carolina’s leaders immediately agreed on a special secession convention, to be held in Columbia, the state capital, on December 17, 1860. But when the delegates gathered there, they heard rumors that a minor small pox epidemic might be breaking out in Columbia so they transferred to Charleston. Three days later, on the afternoon of December 20, the delegates, without any debate, voted to cut all ties with the federal government. If declarations were sufficient, South Carolina had just made itself independent. Church bells in Charleston pealed. Men enthusiastically waved the state’s banner, the Palmetto Flag. Taverns filled with happy and soon-damp roisterers. Citizens set off firecrackers. The celebrants cheered each other till after midnight.

Across the harbor, at Fort Moultrie, soldiers could hear the sounds from the city, the rockets, the erratic pistol fire, the roar of a cannon. Some of the garrison had been born either in the North or in the Border States (the unofficial designation for the northernmost eight slave states, stretching from Delaware and North Carolina to Arkansas and Missouri), but most of the men at the fort had actually arrived in America as immigrants. All had chosen employment in the army, had taken an oath to the American flag, giving their allegiance to the United States. They were, in other words, different from the joyful whites in Charleston, who were celebrating their own way of life, which definitely and explicitly included the institution of slavery. The Civil War was still months away, but right here, on this day, within Charleston Harbor, it was obvious a conflict approached involving South Carolina vs. Major Anderson and his men—unless something happened in Washington to change things.

The president of the United States was James Buchanan. Until March, when Abraham Lincoln took his oath of office, “Old Buck” would be commander-in-chief of the nation’s military.

Nowadays, Buchanan is often named one of America’s worst presidents, and his hesitance during the next four months is the primary reason. It is easy to criticize Old Buck’s indecision about how to handle events in Charleston Harbor, but any honest appraisal of his actions ought to offer realistic options he might have tried. He did not accept the right of secession. Should he have taken a “forceful hand” with South Carolina? If so, how? Neither his army nor his navy was impressive in size or strength, and both were widely scattered—the army manning forts in distant places like California and Texas, the navy far off around the globe. It would take many months to gather either one, so neither could be ready for action till long after Lincoln had taken his oath of office. There was a second factor. Suppose Buchanan did call some of his soldiers to gather. Where? Washington was south of both Maryland and Delaware, two slave states which had some sympathy with South Carolina. Virginia lay just across the Potomac from the capital, and as the most populous slave state, and the most prestigious with by far the greatest industrial capacity to make guns, Buchanan certainly wanted to keep Virginians happy. Buchanan might have used his constitutional prerogative and called on the governors to send militiamen. But would many of them do so? Would any of them do so? South Carolina had not actually done anything other than offer a lot of rhetoric, talking about how special they were, and grab a couple of federal buildings in Charleston. Such activities seemed little more than an annoyance. To be sure, permitting secession to go unopposed would be a bad precedent, but most governors at that moment still thought bloodshed could, and should, be avoided.

After discussing this matter with several strong-willed advisers, President Buchanan did approve a dramatic gesture. His government would send Anderson’s garrison provisions. An unarmed commercial ship, the Star of the West, was hired in New York City, loaded with foodstuffs and other non-military supplies like candles and blankets, and sailed southward. At dawn on January 9, 1861 it approached Charleston’s harbor. It might have entered, but the South Carolinians had prepared for such an intrusion by placing militia volunteers with cannon on beaches at the entry. As the Star approached the harbor, these guns opened fire. The civilian captain of the unarmed ship decided it would be absurd to try to run this blockade, and he turned his ship and headed back to New York.

When Buchanan learned of this, his resolve, never especially sturdy, dissolved. Lincoln would be coming to the capital in less than eight weeks. Since this secession crisis seemed to be caused by his election, let the Illinois Republican deal with it.

Meanwhile Fort Moultrie’s garrison had already taken some dramatic steps of their own. Even before South Carolina officially seceded on December 20, Major Anderson had analyzed his situation. Given the personal contacts the garrison had in the city, the soldiers knew about the turmoil there. The approach of secession was hardly a secret. The only question involved whether secession would lead to a more aggressive temperament toward Fort Moultrie, the most salient symbol of federalism near Charleston. The major assumed it would, and since the walls of his fort could be easily approached by local militiamen and cannon, it seemed prudent to consider the options. The most obvious question was whether Washington—that is, the army or the White House—would order Anderson to withdraw from the area peacefully, leaving Moultrie to the South Carolinians. Washington answered quickly: Anderson and his garrison were told to remain. (In other words, the much-maligned Buchanan did choose to stand firm on that issue.) It would be Major Anderson’s responsibility to calculate how to accomplish that feat.

With this in mind, Anderson began to eyeball Fort Sumter, a couple of miles away. If he moved the garrison there, they would be far more secure. It also occurred to him that Fort Moultrie’s weakness might entice South Carolina into an open military act. Anderson, with his mild manners and his Border State roots, definitely wished to avoid anything that might provoke a war. As he wrote his superiors in Washington, he wished “to prevent the effusion of blood.” Ironically, what he was about to do was both determinedly peaceful and enormously provocative.[2]

Fort Sumter’s advantageous position atop an island in the harbor was hardly lost on Governor Pickens and his advisors. During the days after secession, two small boats departed Charleston every day and drifted by Fort Moultrie to spy on activities there. Anderson watched them.

Christmas arrived and Charlestonians celebrated that holiday. At Fort Moultrie things remained apparently calm, as usual. Anderson kept his own counsel but suggested his officers attend Christmas church services. The following day, December 26, 1860, was chilly. A dank fog lay across the harbor all day. Major Anderson made his decision. He would secretly transfer the garrison to Fort Sumter. The move across the harbor could be hazardous. If the secessionists learned of his plan, as the tiny garrison rowed itself across—a process that would likely take several hours—South Carolinians might rush to Moultrie, capture the fort, and turn its guns on the federal soldiers. Up to now, Anderson had not discussed his thinking with any of his officers. Then, suddenly, after dark that day, he gave orders. They would transfer to Fort Sumter, immediately.

Remarkably, everything went according to his plan. By late that night Anderson and his soldiers were ensconced on the obscure island across the way, which they were about to make famous. (The women, children, and provisions followed without hindrance.)

The next morning the mood in Charleston was churlish. As far as Francis Pickens was concerned, Robert Anderson had just committed an unacceptable act of larceny. According to the thinking of South Carolina’s secessionist leaders, the state had merely loaned small portions of its lands (like Forts Moultrie and Sumter) to the federal government, and now with secession, the state naturally wanted its property returned. Representatives bearing this message soon arrived at Fort Sumter. Major Anderson met them politely, heard them out, and declined to evacuate—unless the authorities in Washington ordered him to do so. (He knew for a fact, from messages he had received, that Buchanan wanted him to stay. He was uncertain about Lincoln’s opinion, but that question seemed far off.) During the next few weeks both South Carolina and Fort Sumter prepared for some sort of action. But it remained unclear what would happen next. Pickens wanted to attack Sumter right away. Jefferson Davis, who had not yet resigned his seat in the United States Senate, heard this rumor and wrote the governor that the “little garrison in its present position presses on nothing but the point of pride.” Davis added, “Stand still.” The Mississippi senator knew that secession was spreading, and South Carolina would soon have comrades in arms.[3]

One by one, the other six Deep South states from Georgia and Florida to Texas voted to secede. By February, all seven considered themselves out of the Union. The next step, they agreed, was to gather in Montgomery, Alabama to form a new government that would represent their unity. On February 4, 1861 fewer than forty delegates of six Deep South states met. (Texas’s delegates were not attending as yet, since Texas was still awaiting their official state results.) After several days of bombastic speechifying, on February 9 they—now calling themselves the Confederacy—simply adopted the eight volumes of United States statutes, then chose Jefferson Davis to be their acting president. Although Davis was not universally popular with the delegates, they appreciated his military background as a graduate of West Point, the well-known fact that he had been a notable fighter in the Mexican War, plus his successful experience as Secretary of War. Given the ticklish situation in Charleston Harbor, these military aspects of his résumé seemed important.

From that moment the problem of what to do about Fort Sumter lay in the lap of Jefferson Davis. One of his first decisions was to send a military representative to Charleston to take charge of the situation. He chose a man who had just resigned a position as military engineering officer in the American army, well-acquainted with matters involving fortress walls and cannon, the Louisianan Beauregard, naming him the first brigadier general of the Confederacy.

Beauregard left by train for Charleston right away. On arrival, he realized many guns were badly placed and ordered corrective actions. In a few weeks, under his direction, teams of men had wrestled assorted cannon into place until the islands around the harbor bristled. Fort Sumter, itself, was the focus of most of these cannon, but some faced the harbor’s mouth, thereby cutting off Anderson’s garrison from receiving outside reinforcements or food.

As Beauregard stared across the waters at Fort Sumter, he dreaded the prospect of firing on his mentor, Major Anderson. When Beauregard was at West Point, his teacher Anderson had befriended the young cadet, often inviting him to dine with the family. Both still retained deep affection and respect for one another. In a letter Beauregard called the major “a most gallant officer.” He also sent cases of brandy and whiskey to his friend, but the commander of Fort Sumter politely, but punctiliously, returned them, unopened. [4]

Events moved faster then. This increased tempo was partly due to events far from the harbor, as Americans, North and South, grew aware of the critical importance of the fort as a symbol of federal power inside the heart of secession. Also, supplies were dwindling at Fort Sumter. Anderson had sent away the wives and children in January. Partly, this was to keep them out of harm’s way, but mainly, this was due to the fact that the fort was running out of provender. Increasingly, the garrison was forced to cut back on its use of kindling for fires to keep warm, on candles to provide lighting after dusk. But the chief shortage remained food. They could cut back on their daily rations, and did. Yet, inevitably, soon, Anderson and his men would run out of food. He informed army headquarters they could not hold out much longer, no more than a few weeks. Secretary of War Henry Holt received this message in early March and felt it necessary to tell the incoming president.

Things were changing in the nation’s capital. On March 4, 1861 the lawyer Abraham Lincoln, having just arrived from Springfield, Illinois, took his oath of office. The following morning, his first full day in office, Secretary Holt handed him the major’s message about the fort’s declining provisions. The new president, four years younger than Anderson, a fellow Kentuckian by birth, already had reservations about the major. He now wondered: Was Anderson loyal, or was he exaggerating the “food shortage” as an excuse for abandoning the fort? Lincoln asked around, and received mixed reports, but General Winfield Scott, when asked, completely supported the major’s honesty. The general also offered his analysis of Fort Sumter’s situation. He said he saw no realistic way it could be resupplied, and it ought to be surrendered. He told Lincoln it might be reinforced with a large fleet and an army of 25,000 but this, he considered, absurd. The entire American army at that moment was less than 16,000 (and rapidly dwindling in size as Southerners departed from it). Furthermore, to increase the army’s manpower would require an act of Congress, which was not even in session, and could not be realistically called up for weeks, by which time Fort Sumter’s garrison would have long since run out of food.

On March 9, at Lincoln’s first cabinet meeting, he announced that General Scott thought Sumter should be evacuated. His words stunned the gathering. Taking this action would not only humiliate the new administration, but it might fatally damage the Republican Party, only in existence for seven years.

In fact, however, the new president himself felt unsure whether abandoning the fort was wise. Six days later he raised the topic again with his cabinet. This said he wanted each to think deeply about the matter, then individually to write up a recommendation. The replies, when they trickled in, were mixed. One or two cabinet members thought the administration should hold firm to the fort. The others responded: Perhaps Sumter might be supplied, but that doing so would be imprudent. Lincoln, after reviewing their opinions, still hesitated. He was beginning to think that General Scott’s reports were not derived solely from military factors. Lincoln noticed that the old general was beginning to offer non-military analysis, such as Scott’s judgments about the mood in the Border States. Lincoln grew annoyed with the general over this, but in Scott’s defense, military “strength” at that moment did depend quite a bit on how each of the Border States reacted to this crisis. And, in truth, Border State politicians avidly read news accounts of events in Charleston, knowing that events there could easily alter what happened along the border.

In late March Lincoln decided to embrace a plan to send Fort Sumter provisions, and even reinforcements. Preparations took place in New York City to ship soldiers and food southward. It was this expedition that caused the Confederacy to open fire, and therefore led to war.

(Though Abraham Lincoln never later admitted it, at this critical juncture he may have accepted—perhaps even desired—the prospect that provisioning Sumter might lead to war. He may have wanted to maneuver Jefferson Davis into a hostile attack on the tiny garrison, and thereby enflame outside opinion against the Confederacy. Some suspicious analysts, with no proof in hand, have suggested this was Lincoln’s motivation.)

As President Lincoln was quietly piecing his plan together, the men of Fort Sumter’s garrison were feeling isolated and alone and misunderstood. They could observe work intensifying on the cannon all around them. A single hope kept the garrison going. They believed that Washington would soon relieve them of their duties at the fort, and they could then sail peacefully home. A few visitors to the fort, representing Lincoln, seemed to assure them this would happen.

Meanwhile, Major Anderson himself felt weary and helpless. He constantly sent messages to Washington, about a hundred of them, pleading for clearer instructions. He seldom heard back. All he, and the rest of the garrison, could do was wait. Politicians, North and South, would decide their fate.

Although the garrison had already cut back their daily diet, their food would obviously disappear soon. On April 1 Anderson decided he could wait no longer. He wrote his superiors that provisions would be gone in “about one week,” perhaps earlier.

Three days later Lincoln read these words and was aghast. He had assumed the fort could hold out longer, that he, the president, had more time. But this latest note from the fort dissuaded the president, and he sent Anderson a new and crucial message. A relief expedition was on its way.

When Anderson heard this news, he felt desolate. He understood too well what this almost certainly meant

Abraham Lincoln, simultaneously, decided he ought to officially inform the Confederates about these ships headed toward Charleston Harbor. When Jefferson Davis received this information, he wired General Beauregard that Anderson must surrender Fort Sumter immediately, and if not, Beauregard should open fire.

On April 11, 1861 three of Beauregard’s aides rowed to the fort with this message. They and Anderson conversed about the issue in a civilized fashion, but the major refused to back down. It was 3:20 in the morning of April 12 as the aides stepped into their small boat to return. As they departed, Anderson calmly asked how long it would be before guns opened fire on his fort. One of the aides sadly replied, “In one hour.” And thus the Civil War was about to open.

At about four-thirty that morning a signal gun fired into the darkness, telling all the Confederate cannon to start hammering Sumter’s walls. The bombardment began. The Confederates had far more guns and manpower. Anderson ordered his men to fire back. (As the fight unfolded, Lincoln’s little relief fleet arrived outside the mouth of the harbor. It was too late for them to offer any assistance to Anderson. All they could do was sail back and forth, and watch in frustration.)

There could be no question which side would win this unequal conflict. But the fort’s thick walls offered excellent protection to Robert Anderson’s little band of defenders. Flagstaffs snapped off, gouges appeared in the bricks, the three main buildings within the outer walls grew rather badly damaged. Miraculously, the men inside remained unscathed. But as the hours of constant hellish bombardment dragged through the first full day and into the second, strain and exhaustion and hunger took their toll. Late on the morning of Saturday, April 13, Major Anderson conceded defeat. All he asked in return was the right to take down his flag in full dignity, with proper honors. Beauregard understood, and granted the request. He also allowed the little garrison an additional day to gather their things before departing on a boat that would carry them to Lincoln’s ships outside the harbor.

On Sunday, April 14, 1861, the garrison stood on Sumter’s parade ground and watched their flag lowered. Cannon on the platforms above them fired a salute to their ripped and charred flag. Tradition called for fifty rounds. Throughout Charleston and the harbor islands men who would soon be at war listened to the banging guns. Twenty shots, thirty, forty. On the forty-seventh round one cannon exploded. (Two members of the garrison died as a result, Anderson’s only two casualties throughout this long weekend). Then, after a pause, three more guns at the fort fired. The salute to the American flag was complete. Robert Anderson’s work here was done. The rest would be up to history.

- [1] David Detzer, Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, 93.

- [2] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 1, p.89 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 1, 89).

- [3] Jefferson Davis to Francis Pickens, Washington D.C., January 20, 1861, in Lynda Lasswell Crist, et al., eds., The Papers of Jefferson Davis, vol. 8 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 23-5.

- [4] Beauregard to L.P. Walker, Secretary of War, Charleston South Carolina, March 26, 1861, O.R., I, 1, 282-3.

If you can read only one book:

Detzer, David, Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001.

Books:

Chesnut, Mary Boykin & C. Vann Woodward, ed. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War. New Haven Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1981.

Crawford, Samuel Wylie. The Genesis of the Civil War: Fort Sumter, 1860-1861. New York: Charles L. Webster, 1887.

Davis, William C. “A Government of Our Own”: The Making of the Confederacy. New York: The Free Press, 1994.

Welles, Gideon. Diary of Gideon Welles. 3 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911.

P. G. T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1955.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Fort Moultrie: Constant Defender. This is a book available on line and written by staff of the National Park Service which provides a history of Fort Moultrie. It can be accessed and read on line.

Other Sources:

Robert Anderson Papers, 1819-1948

Robert Anderson’s personal papers are kept at the Library of Congress. The Library’s finding aid isFort Moultrie

Fort Moultrie is part of Fort Sumter National Monument and can be reached by car. The Fort is located at 1214 Middle Street, Sullivan’s Island SC, (843) 883 3123. The Fort is open from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily except New Year’s, Thanksgiving and Christmas days.Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter can be reached by the concession-operated ferry from two locations, the Fort Sumter Visitor Education Center (340 Concord Street, Charleston SC) and the Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum (40 Patriots Point Road, Mount Pleasant SC).The Battery

The Battery is a landmark defensive seawall and promenade in Charleston SC which was used to shell Fort Sumter and today provides a sense of the Fort’s position in the harbor as well as a display of Civil War era cannon. The battery can be reached by car and is located at 5 East Battery Street, Charleston SC.