Harpers Ferry

by Jon-Erik Gilot

For nearly six years the site described by Thomas Jefferson as “one of the most stupendous in nature” and “worth a voyage across the Atlantic” would see sustained combat, bloodshed and military occupation rivaled by few peers of its size during the American Civil War. Harpers Ferry, Virginia, situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, had been founded in 1763, attracting visitors not only for the ferry crossing on the Potomac River but for the picturesque beauty of the area. Federal armories and a rifle works were constructed at Harpers Ferry which was the site of John Brown’s famous raid in 1859. As a gateway to the Shenandoah Valley and a transportation hub, the town was fought over continually during the war. In April 1861 the small federal garrison burnt the arsenal buildings in the face of advancing Virginia militia. The Virginians were able to salvage much of the machinery to send south where it was used to manufacture arms for the Confederacy throughout the war. In May 1861 the Confederates withdrew from the town, first setting fire to the armories and the B&O railroad bridge. In October 1861 a battle was fought on Bolivar Heights. In the spring of 1862 Stonewall Jackson attempted to take the town, but gave up in the face of strong federal resistance. As part of the invasion of Maryland, Confederate troops converged on Harpers Ferry and at the Battle of Harpers Ferry on September 12-15, forced the surrender of the entire federal garrison taking 13,000 prisoners and canon, rifles, wagons and other war materiel. When they left the town a few days later the Confederates burned it and destroyed the B&O bridge again. The federals reoccupied the town after the Confederates left. The town experienced a quiet period until July 1863 when the rebuilt B&O bridge was again destroyed, this time by the Federals to prevent the Army of Northern Virginia, retreating after Gettysburg, from crossing the Potomac at Harpers Ferry. Another quiet period ended in January 1864 with a series of attacks on railroad property and federal troops by Confederate raiders. In May the B&O bridge was again destroyed this time by floodwaters in the rivers. In July 1864 advancing Confederate troops forced the garrison at Harpers Ferry to retreat to fortifications on Maryland Heights above the town, which they did after destroying the recently repaired B&O bridge and a temporary pontoon bridge to prevent the Confederates from advancing. The Confederates shifted their advance to the north, crossed the Potomac River at Shepherdstown and attacked the Federal garrison on Maryland Heights for three days. During this fighting the lower town again suffered damage from canon fire which fell from the battle on the heights above. The battle ended when the Confederates withdrew. The federal garrison was greatly strengthened and a series of battles took place in the area during the rest of 1864, but none in Harpers Ferry proper. The final winter of the war saw continued Confederate partisan attacks in the Harpers Ferry neighborhood. With the war’s end, marked by four years of almost continual warfare, the town presented a scene of destruction and desolation. Eventually rebuilt, Harpers Ferry was designated at

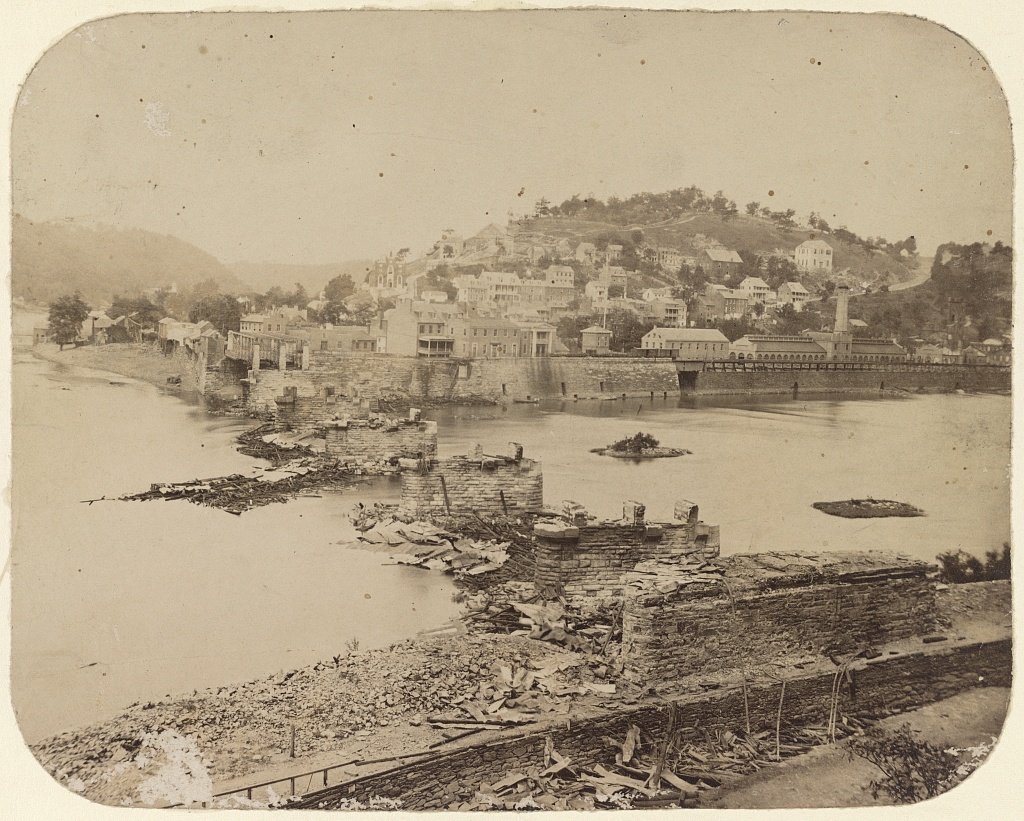

Harper's Ferry, photographed immediately after its evacuation by the rebels. 1861, by C. O. Bostwick.

Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

For nearly six years the site described by Thomas Jefferson as “one of the most stupendous in nature” and “worth a voyage across the Atlantic” would see sustained combat, bloodshed and military occupation rivaled by few peers of its size during the American Civil War.[1] Harpers Ferry, Virginia, situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, had been founded in 1763, attracting visitors not only for the ferry crossing on the Potomac River but for the picturesque beauty of the area. Following the American Revolution, congressional legislation provided for the establishment of federal armories, and with its reliable waterpower, forests and mineral deposits, and its location nearby the new capitol at Washington, DC, Harpers Ferry was chosen as one of two locations. By 1796, 125 acres of land had been purchased and within its first decade the armory produced thousands of stands of small arms for the nation’s fledgling military.

New England gunsmith John Hall constructed a rifle works on a nearby island in the Shenandoah River, which was later acquired by the War Department, increasing the footprint of the federal installation at Harpers Ferry. More than 400 workers were employed at the armory, swelling the local population to more than 3,000 by the eve of the Civil War. Harpers Ferry was also a transportation hub, with the C&O canal hugging the Potomac riverbank and the Baltimore & Ohio and Winchester & Potomac railroads running through town.

Yet Harpers Ferry was also located firmly within the grasp of slavery, the 1850 census counting nearly 4,000 slaves in Jefferson County, Virginia. African Americans, both slaves and free, accounted for approximately 10% of the Harpers Ferry population on the eve of the Civil War. And so it was not by happenstance that radical abolitionist John Brown had dispatched one of his men to Harpers Ferry in the spring of 1858 to scout the local area, where the following year Brown initiated his long planned strike against slavery.

From October 16 – 18, 1859, John Brown and 18 men raided the armory, arsenal and rifle works at Harpers Ferry while taking several local citizens as prisoners. After hours of fighting and negotiations between Brown and local citizens and militia, a detail of United States Marines arrived from Washington, DC under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. The troops stormed a small engine house where Brown and the last of his men had holed up, killing several and capturing others. Brown was himself badly wounded and captured, and was quickly tried in nearby Charles Town, where he was sentenced to death by hanging on December 2, 1859. Like Thomas Jefferson, Brown marveled at the local landscape, remarking that it was “beautiful to behold” while on his way to the gallows.[2] He also prophesized the coming conflict that would ravage the Harpers Ferry area in the coming years: “I John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty: land will never be purged away; but with blood.”[3]

Situated betwixt north and south, Harpers Ferry residents perhaps felt a sense of foreboding during the winter and spring of 1861 as the country spiraled towards civil war. As a doorway to the Shenandoah Valley and a transportation hub, the area was sure to become an avenue for waring armies. Following the attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers prompted Virginia to secede from the Union on April 17. The following day at Harpers Ferry a speech by Alfred M. Barbour, late superintendent of the armory turned delegate to the Virginia secession convention, “excited the anger of unionists to a high pitch” as he urged armory workers to remain loyal to the state.[4] Virginia governor Henry Wise had already set events into motion, theatrically brandishing a pistol and his pocket watch on the convention floor in Richmond and declaring “armed forces are now marching upon Harpers Ferry… and there will be a fight or a footrace before the sun sets this day.”[5]

Defending the arsenal complex at Harpers Ferry was a detachment of a mere 42 Federal troops under the command of Lieutenant Rogers Jones. On receiving intelligence that Virginia militia was approaching with orders to seize the armory and arsenal complex, Jones ordered the buildings destroyed and retreated into Pennsylvania. “A loud explosion and a thick column of fire and smoke” greeted the approaching Virginia militiamen, with Lieutenant Jones noting that within “three minutes, or less,” the sprawling government complex had been engulfed in “a complete blaze.”[6] While thousands of stands of arms were destroyed, the Virginia troops were able to salvage some of the arsenal machinery, which was sent south to produce arms for the Confederate war effort for the remainder of the war.

The Virginia troops were in no hurry to leave Harpers Ferry. By April 19, some 2,400 Virginia militia had arrived. Colonel Thomas Jonathan Jackson, recently of the Virginia Military Institute, was dispatched to Harpers Ferry to organize the growing mass into a military force. Under Jackson’s direction the disparate companies were organized into regiments, and the regiments into a brigade, later dubbed the famed ‘Stonewall Brigade.’ Where one Virginia militiaman amazed at “the lightheartedness with which all duty was done” prior to Jackson’s arrival, another described the transformation after his arrival, noting “the presence of a master mind was visible in the changed condition of the camp. Perfect order reigned everywhere.”[7]

Jackson fortified the three heights towering above the lower town – Maryland, Loudoun, and Bolivar Heights. May 1861 saw the Confederate command at Harpers Ferry swell to more than 8,000 men, and along with them a new commander in Brigadier General Joseph Eggleston Johnston. Within weeks Johnston decided to abandon Harpers Ferry, preferring what he deemed to be a more defensible position at nearby Winchester, Virginia. As the Confederates departed Harpers Ferry the town again witnessed wholesale destruction for the second time in as many months. Johnston’s men set fire to the armory buildings on Hall’s Island and the impressive B&O railroad bridge, one citizen recalling “a loud explosion and seeing the debris of the destroyed bridge flying high in the air.”[8] Just a few weeks later, bent on more destruction, Confederate troops returned to torch the rifle factory on Hall’s Island and the covered bridge across the Shenandoah River.

Harpers Ferry would not remain idle for long. Indiscriminate skirmishing on July 4claimed the life of Harpers Ferry civilian Frederick Roeder, the first civilian life claimed since John Brown’s Raid, though not the last of the war. In this interlude a local citizen witnessed “the rapid demoralization of the people at this time and the various phases of corrupt human nature suddenly brought to light by the war,” including robbery and plunder of both government and private property.[9] Two weeks later the town was occupied by some 6,000 troops of General Robert Patterson’s command, though Patterson was soon replaced with political general Nathaniel Prentice Banks.

Banks opted to move his command across the Potomac River to nearby Sandy Hook, before relocating further to Frederick, Maryland, again throwing Harpers Ferry into a painful interregnum. One modern historian believing that “perhaps no town in America suffered the trials and tribulations of war more than Harpers Ferry during the late summer and fall of 1861.”[10] Routine skirmishing devolved into a battle on October 16, 1861, as a small Federal command tasked with seizing local wheat and flour had repulsed multiple attacks by Confederates under the command of Colonel Turner Ashby. The Federal troops counterattacked, driving the Confederates from the field and capturing one cannon. The Battle of Bolivar Heights resulted in few casualties and marked the first of numerous battles in the Harpers Ferry environs, one Massachusetts soldier writing that he “fought 8 hours against fearfull [sic] odds” but “never saw such daring bravery” as exhibited during the battle.[11] Following the battle Harpers Ferry would slip into “an ill-boding lull,” the town presenting “a scene of the utmost desolation.”[12]

On February 7, 1862 Colonel Geary returned to Harpers Ferry, this time to burn a section of the business district near the B&O railroad trestle where Confederate snipers would often conceal themselves. Described by one citizen as “wanton destruction of property,” the fire once again consumed a swath of the lower town.[13] Later that month a pontoon bridge was thrown across the Potomac, followed in March by a reconstructed B&O bridge, reopening an avenue for Federal forces to enter the lower Shenandoah Valley. In March, a new federal commander was assigned to the Harpers Ferry district. Brigadier General Dixon Stansbury Miles was ordered take command of a new Railroad Brigade, tasked explicitly with protecting the vital Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, Abraham Lincoln’s lifeline to the west. These troops would to be dispersed to strategic stations and bridges along the vast stretch of the B&O, leaving Harpers Ferry itself void of any substantial force for defense. This proved problematic when in the spring of 1862 Confederates again threatened Harpers Ferry.

After dispatching troops under generals John C. Frémont and Banks from the upper Shenandoah Valley, Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson again trained his sights on Harpers Ferry. Some 8,000 Federal troops were rushed to Harpers Ferry, occupying Bolivar and Maryland Heights, constructing a naval battery at the latter location and training the guns ominously on the village below. This battery included two 9-inch Dahlgren naval guns, and one 50-pound cannon, designed to command the lower town and the opposing Loudoun and Bolivar heights. These were larger guns than your average field pieces and could cover greater distances. On May 28 Jackson arrived at the doorstep to Harpers Ferry, testing the strength of Federal positions on Bolivar Heights and Camp Hill above the lower town. After sharp fighting Jackson withdrew south, the Federals maintaining control of Harpers Ferry. The area passed a quiet summer as fighting shifted again to the upper Shenandoah Valley, the outskirts of Richmond, and northern Virginia. This interlude would soon end, as the waning days of summer brought the warring armies back to the lower valley.

Following a string of victories at Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, and Chantilly, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia set their sights on the border state of Maryland. In September 1862 they swiftly occupied Frederick, within earshot of the nervous civilians and troops at Harpers Ferry. Unwilling to leave the Federal garrisons at Harpers Ferry and nearby Martinsburg operating in his rear—the two commands totaling some 14,000 troops—Lee divided his army in the face of Major General George Brinton McClellan’s Army of the Potomac quickly chasing after him. Lee detached a full two-thirds of his army, some 28,000 men, south of Frederick to invest Harpers Ferry. One column under Brigadier General John George Walker was ordered to approach through Loudoun County and occupy imposing Loudoun Heights. Another column under Major General Lafayette McLaws was ordered to advance down Pleasant Valley and occupy Maryland Heights, while a third column under General Stonewall Jackson was ordered to cross the Potomac above Harpers Ferry and cover the approach to Bolivar Heights. The plan offered the Harpers Ferry garrison no means of escape.

Dixon Miles’ command dug in on Maryland Heights, Bolivar Heights, and Camp Hill. Many of his troops had never been in battle, some regiments having been under arms only a matter of days. Miles scoffed that some of the men “never had a gun in their hands,” and that the officers were as ignorant of drill as the men they commanded.[14] That would soon change, as on September 13 Walker’s men captured Loudoun Heights and Jackson’s men occupied School House Ridge, opposite Bolivar Heights. McLaws men advanced on Maryland Heights, where Federal troops occupied the heights and the naval battery below the summit. After nine hours of determined fighting by these raw, inexperienced troops, Maryland Heights was abandoned. Though Miles still commanded an advantageous position at Bolivar Heights, his command had been essentially sealed off from reinforcement or retreat.

Jackson ordered Walker and McLaws to position artillery on Loudoun and Maryland Heights, commanding the lower town and the rear of the Federal lines on Camp Hill and Bolivar Heights, while Jackson’s artillery covered their front. The Confederate cannons opened on the afternoon of September 14 and continued throughout the day. That evening, a column of some 1,400 cavalrymen quietly crossed the Potomac River, intent on escaping capture and finding reinforcements to rescue the Harpers Ferry bastion. Understanding his strict timeline was in jeopardy, Jackson began redeploying troops his troops for an attack on the Federals still clinging to Bolivar Heights. The battle was renewed the following morning, but with ammunition nearly exhausted and cut off from any avenue of escape, Miles called a council of war, the meeting held “in the midst of shell and round shot.”[15] His commanders agreed that the further effusion of blood was useless, and all agreed to surrender.

As word was passed along the Federal lines to raise the white flag, Confederate batteries had once again opened, with one shot grievously wounding Miles. According to one of his aides, Miles remarked on his deathbed that “he had done his duty; he was an old soldier and willing to die.”[16] He was removed to his headquarters at the master armorer’s house, where he soon expired.

Stonewall Jackson was no doubt relieved to complete his overdue assignment. In the capitulation at Harpers Ferry, Jackson had captured more than 70 cannons, nearly 13,000 stands of small arms, hundreds of wagons, and more than 1,000 mules, not to mention nearly 13,000 Federal prisoners. The Battle of Harpers Ferry would remain the single largest surrender of United States troops until the 1942 Battle of Bataan. Already running behind schedule, Jackson could not stay long at Harpers Ferry, leaving the following morning to rejoin Robert E. Lee at nearby Sharpsburg.

Rather than being shipped south to Confederate prisons, the Federal troops at Harpers Ferry were paroled, honor bound not to return to the war until properly exchanged. The men were dejected, one Ohio soldier fuming…

Just one year of campaigning, one year of heat, one year of absence from home, from everything civilizing, everything refined, one year spent in unused hardships and all for what? To be at last sold, betrayed, disgraced, captured? Ruined by men who if they strike their hands against a nail see their own blood and feel their courage fail?[17]

These troops were sent to various camps to await their exchange. Many of these men, like those of the 126th New York Infantry, who had been under arms for mere days before the surrender, would suffer the mocking moniker of “Harpers Ferry Cowards” until they redeemed their reputations later in the war.

Harpers Ferry would have little time to recover. Fire again engulfed the town on September 18, the Confederates burning anything that could not be carried away. For the fourth time during the war the B&O Bridge was destroyed, as was the pontoon bridge, along with other railroad and armory property. The following day Union troops once again reoccupied Harpers Ferry, with more arriving each day following the battle at Antietam. One local resident recalled that the area “soon became dotted with tents, and at night the two villages and the neighboring hills were aglow with hundreds of watchfires.”[18] President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Harpers Ferry on October 1 – 2 to review his army and urge its general, George B. McClellan, to pursue the Confederate army.

McClellan would not move far and was soon removed from command of the Army of the Potomac. Still, Little Mac initiated work on substantial fortifications that would ring Harpers Ferry and alter the landscape for generations. The most substantial work was a stone fort at the crest of Maryland Heights, constructed from the plentiful stone and boulders found on the bluff. Some 12,000 men wintered at Harpers Ferry into 1863, offering protection to the Baltimore & Ohio and something of a reprieve to the local citizenry.

That reprieve came to an end by June 1863. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, fresh off a resounding victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville began moving north towards Pennsylvania, Lee’s second invasion of the north in less than a year’s time. The Federal garrison at nearby Winchester was swept out of town in the face of Lee’s advancing army, streaming into the Harpers Ferry defenses. Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, commander of the Harpers Ferry garrison, scoffed that “demoralized troops…from Winchester, are not the troops to defend [Harpers Ferry],” and determined to remove his garrison to the commanding position on Maryland Heights.[19] There Tyler planned to make his stand should the Confederates once again bear down on Harpers Ferry. While some Confederate troops did occupy the lower town, Robert E. Lee would bypassed the Harpers Ferry garrison during this second invasion, instead moving into south central Pennsylvania.

Tyler’s garrison remained on Maryland Heights until June 29, when he was ordered to move to nearby Frederick to cover the rear of the Army of the Potomac. Following the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, Maryland Heights was again reoccupied. Aiming to prevent the retreating Army of Northern Virginia from crossing at Harpers Ferry, the B&O Bridge was once again destroyed. The Confederates instead skirted Harpers Ferry, crossing the Potomac upstream at Williamsport. A temporary pontoon bridge was thrown across the Potomac and three corps of the Army of the Potomac crossed there, pursuing the Confederates south. For some Federal troops it was their first time back in Harpers Ferry since the previous year. One Pennsylvania chaplain recalled Harpers Ferry as “so romantically, so vividly, so beautifully, so strongly situated – so full of sad memories to us who spent our first weeks of military life there, were there initiated in its hardships and suffering, and there lost so many beloved friends.” The same chaplain “thanked God that we were not again required to stay at that unhealthy and unpleasant place.”[20]

The summer of 1863 brought further change to Harpers Ferry in the way of a new state. Tensions between eastern and western Virginia had simmered for decades, but civil warfare and Virginia’s secession from the Union provided the impetus for separation between the two parts. Since 1861 delegates from the western counties had been meeting in the northern panhandle city of Wheeling, intent on forming a new state loyal to the Union. After a series of conventions and referendums, President Abraham Lincoln signed the statehood bill on December 31, 1862, paving the way for West Virginia to become the 35th state on June 20, 1863. The new state had a protruding eastern panhandle, with the counties of Jefferson, Berkeley, and Morgan, included in the new state as a means of protecting the critical transportation lines along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. The admission of Berkeley and neighboring Jefferson—the location of Harpers Ferry— drew the ire of Virginia and would continue to be argued after the guns fell silent.

The B&O Bridge was repaired by the end of July 1863 and rail service restored. The Harpers Ferry area passed a quiet remainder of the summer and autumn, with only infrequent skirmishing and guerrilla activity to occupy the garrison’s attention. This quiet period ended on January 10, 1864 when a detachment of Confederate cavalry under Colonel John Singleton Mosby attacked a Federal camp on Loudoun Heights. Such attacks against railroad property and Federal troops continued throughout the winter. Mother Nature would also wreak havoc on railroad property, with floodwaters damaging the B&O Bridge on April 10 and again on May 16, this time collapsing the span. The Baltimore & Ohio Company, now adept at damage-control after three years of warfare, had a new bridge built within one week’s time.

This situation at Harpers Ferry continued through the winter and spring of 1864, though events would soon pull the town back into the war. Facing unrelenting pressure from the advancing Army of the Potomac, Confederate General Robert E. Lee dispatched 14,000 men under the command of Major General Jubal Anderson Early to the Shenandoah Valley, hoping to draw troops away from the Army of the Potomac and perhaps threaten the weakened Federal garrison protecting Washington. After dispatching a Federal army at Lynchburg, Early moved quickly down the valley and by July 4 was bearing down on Harpers Ferry, once again sending the Union garrison across the Potomac to the safety of Maryland Heights. “It was time for the yearly ‘skedaddle,’ which is as sure to come as Christmas itself,” remarked one jaded Federal soldier.[21] A local resident recalled that “at every evacuation of the place the wildest excitement pervaded the town, and scenes of terror were frequently presented, mingled with ludicrous occurrences.”[22] The Federal troops removed the pontoon bridge behind them and set fire to the only recently repaired B&O Bridge. Major General Franz Sigel assumed command of the Federal garrison on Maryland Heights and prepared to blunt Early’s anticipated river crossing at Harpers Ferry. “At no time during the war was there as deep a gloom on Harper’s Ferry as on that anniversary of the birth of our nation,” recalled one civilian.[23]

The Confederate army instead shifted north and crossed the Potomac at Shepherdstown before turning south, refusing to leave the Maryland Heights garrison operating in their rear. For three days the Confederates tested the strength of the Federal bastion before ultimately abandoning the effort and moving east towards Frederick. Harpers Ferry and its remaining residents suffered greatly during this latest battle, with cannon fire from Maryland Heights falling on the lower town. At least two civilians were killed, and numerous properties damaged, one enraged Harpers Ferry citizen “remonstrated in strong language with the gunners for doing wanton mischief to inoffensive citizens.”[24]

With the immediate Confederate threat removed, the lower town was reoccupied on July 9, 1864. While the local populace did not know it, this marked the final time of the war that the town would change hands. The B&O Bridge was once again reopened before the end of July and General David Hunter made Harpers Ferry the base of operations for his Army of West Virginia. Hunter would soon be usurped by General Ulysses S. Grant’s handpicked successor, Major General Philip Henry Sheridan, who arrived at Harpers Ferry in early August. Grant instructed Sheridan to carry the war not only to Jubal Early’s army, but likewise to the civilian populace. Harpers Ferry, with its garrison, hospitals, storehouses, and transportation became the nerve center of Sheridan’s massing army, dubbed the Army of the Shenandoah. One Ohio soldier remembered Harpers Ferry at this time as “very dirty…& no wood to cook with.”[25]

Within days of his arrival Sheridan ordered a general advance on Early’s army. The aggressive Early countered and drove the Sheridan’s men back to Halltown, on the outskirts of Harpers Ferry. Once again Harpers Ferry residents could hear the reports of cannon and rifles while Sheridan’s army occupied the heights above Bolivar. Convinced that the Federal position at Harpers Ferry was too strong, Early withdrew to Winchester. Harpers Ferry was spared the horrors of another battle.

Sheridan did not remain in Harpers Ferry for long, defeating Early in a series of battles before routing the Confederate army at Cedar Creek. By the end of 1864 most of Sheridan’s army was recalled to the Army of the Potomac outside Petersburg. The final winter of the war saw continued Confederate partisan attacks in the Harpers Ferry neighborhood, keeping Federal cavalry and the Harpers Ferry garrison on their toes. On April 6, 1865 at Keyes Switch, just west of Harpers Ferry, troops under Colonel John S. Mosby captured the entire command of the Loudoun Rangers, a company of Federal troops recruited in neighboring Loudoun County, Virginia, marking both Mosby’s last fight and the final skirmish in the Harpers Ferry neighborhood. Three days later Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House.

While a limited military presence would continue at Harpers Ferry for another year after the guns fell silent, the majority of the Federal garrison was mustered out on June 30, 1865, though “the cessation of military operations was far from restoring the tranquility that used to reign in this once prosperous and happy little community.”[26] The same resident believed that “no spot in the United States experienced more of the horrors of war than that village.”[27] While other towns may have changed hands more frequently – most notably Romney, West Virginia and nearby Winchester, Virginia – few others could match the sustained destruction that would become the hallmark of Harpers Ferry’s Civil War years. From bridges and railroads to government buildings, churches and private homes and businesses, no one was spared the horrors of war.

In late 1865 New England author John Townsend Trowbridge sojourned throughout the southern states, intent on viewing the principal cities and battlefields of the recent conflict. One of his first stops was at Harpers Ferry. While struck by the natural beauty of the area, marred though it was by four years of continual warfare, the town presented a scene of destruction and desolation. Trowbridge related…

…while the region presents such features of beauty and grandeur, the town is the reverse of agreeable. It is said to have been a pleasant and picturesque place formerly. The streets were well graded, and the hill-sides above were graced with terraces and trees. But war has changed all. Freshets tear down the centre of the streets, and the dreary hill-sides present only ragged growths of weeds. The town itself lies half in ruins. The government works were duly destroyed by the Rebels; of the extensive buildings which comprised the armory, rolling-mills, foundry, and machine-shops, you see but little more than the burnt-out, empty shells. Of the bridge across the Shenandoah only the ruined piers are left; still less remains of the old bridge over the Potomac. And all about the town are rubbish, and filth, and stench.[28]

Looking to the future, Trowbridge believed “…with the grandeur of its scenery, the tremendous waterpower afforded by its two rushing rivers, and the natural advantage it enjoys as the key to the fertile Shenandoah Valley, Harper’s Ferry, redeemed from slavery, and opened to Northern enterprise, should become a beautiful and busy town.”[29] This prediction was realized in 1944 with the town being named a National Monument, and again in 1963 when elevated to Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Today nearly half a million visitors flock to the park each year to take in the beauty and history. Now 160 years removed from the conflict that both devastated Harpers Ferry and ensured its eventual preservation, “time…has happily cured the wounds, through the scars will ever remain.”[30]

- [1] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Boston, MA: Lilly and Wait, 1832), 18.

- [2] Thomas Drew, The John Brown Invasion (Boston, MA: J. Campbell, 1860), 68.

- [3] Oswald G. Villard, John Brown: A Biography Fifty Years After (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910), 554.

- [4] Joseph. Barry, The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry (Martinsburg, WV: Thompson Brothers, 1903), 97.

- [5] Richard E Fast. and Hu Maxwell, The History and Government of West Virginia (Morgantown, WV: Acme Publishing Company, 1906), 95.

- [6] Barry, Strange Story, 99; United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 2, p. 4 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 2, 4).

- [7] Fletcher M. Green, I Rode with Stonewall (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 6; John D. Imboden, “Jackson at Harpers Ferry,” in Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series”, 4 vols. (New York: The Century Co. 1884-1888), 1:122, based on “The Century War Series” in The Century Magazine, November 1884 to November 1887.

- [8] Barry, Strange Story, 105.

- [9] Ibid., 109.

- [10] Dennis. Frye, Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War (Harpers Ferry, WV: Harpers Ferry Park Association, 2012), 37.

- [11] Timothy J. Orr, Last to Leave the Field: The Life and Letters of First Sergeant Ambrose Henry Heyward, 28th Pennsylvania Volunteers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2011), 45 – 47.

- [12] Barry, Strange Story, 121.

- [13] Ibid., 120.

- [14] O.R., I, 51, pt. 2, 766.

- [15] O.R., I, 19, pt. 1, 539.

- [16] Ibid., 540.

- [17] Daniel. Masters, The Seneachie Letters: A Virginia Yankee with the 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Privately printed, 2020), 105.

- [18] Barry, Strange Story, 126.

- [19] O.R., I, 27, pt. 3, 126.

- [20] David T. Hedrick, and Gordon Barry Davis Jr., I’m Surrounded by Methodists…: Diary of John H.W. Stuckenberg, Chaplain of the 145th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995), 91 – 92.

- [21] Lee C. Drickamer, and Karen D. Drickamer Fort Lyon to Harper’s Ferry: On the Border of North and South with Rambling Jour a Civil War Soldier (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1987). 192.

- [22] Barry, Strange Story, 138.

- [23] Ibid., 131.

- [24] Ibid., 130.

- [25] Unidentified soldier of the 170th Ohio National Guard, Diary, Month Day, Year, August 3, 1864.Civil War Times Illustrated Collection, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

- [26] Barry, Strange Story, 140.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] J.T. Trowbridge, The South: A Tour of its Battle-fields and Ruined Cities, and a Journey Through the Desolated States, and Talks with the People (Hartford, CT: L. Stebbins, 1866), 66.

- [29] Ibid., 68.

- [30] Barry, Strange Story, 142.

If you can read only one book:

Frye, Dennis E. Harpers Ferry Under Fire: A Border Town in the American Civil War. Harpers Ferry, WV: Harpers Ferry Park Association, 2012.

Books:

Barry, Joseph. The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry, With Legends of the Surrounding Country. Martinsburg, WV: Thompson Brothers. 1904, chap. 5.

Frye, Dennis E. & Catherine Magi Oliver. Confluence: Harpers Ferry as Destiny. Harpers Ferry, WV: Harpers Ferry Park Association. 2019.

Frye, Dennis E. History and Tour Guide of Stonewall Jackson’s Battle of Harpers Ferry. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Enterprises, 2012.

Hearn, Chester G. Six Years of Hell: Harpers Ferry During the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. New York: Henry Holt, 2011.

Organizations:

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park was established as a National Monument in 1944 and a National Historical Park in 1963. The park encompasses more than 4,000 acres across three states and interprets more than 200 years of history in the Harpers Ferry area. The park’s address is: 171 Shoreline Drive, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425, telephone 304 535 6029. The park is open from 9-5 seven days a week.

Harpers Ferry Park Association

The Harpers Ferry Park Association was established in 1971 and works as a National Park Service cooperating association, providing funding for educational and interpretive enhancements at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, such as certified guide tours and historic trades workshops, as well as aiding in conservation and preservation projects. Their address is 723 Shenandoah St. PO Box 197 Harpers Ferry WV 25425, telephone 304 535 6881.

Web Resources:

The American Battlefield Trust provides exclusive, free content on Harpers Ferry during the Civil War era as well as the organization’s long history in preserving land there.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.