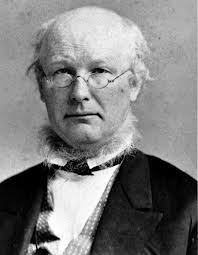

Horace Greeley

by Mitchell Snay

Biography of Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and a leading Republican

“My paramount object in this struggle,” Abraham Lincoln once said, “is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery.” Lincoln’s comment remains one of the more famous and revealing quotes about his attitudes towards slavery during the Civil War. The quote was in response to an open letter published in the August 20, 1862 issue of the New York Tribune. The author of the letter, called “The Prayer of Twenty Millions” – and the editor of the newspaper – was Horace Greeley, one of the most important public figures of the Civil War era.[1]

Horace Greeley was born in New Hampshire and raised in rural New England. Having served a newspaper apprenticeship in Vermont, Greeley went to New York City where he would spend the rest of his editorial career. In 1834, Greeley began publishing The New Yorker, a newspaper that revealed his strong connection to the ideals and policies of the Whig Party. During the election of 1840, Greeley published two short Whig partisan newspapers. In 1841, he founded the New York Tribune, which would become one of the nation’s leading newspapers. During the 1850s, Greely became a major figure in the formation of the Republican Party. He ran unsuccessfully for president in 1872 on the Liberal Republican ticket and died shortly thereafter.

Greeley had a well-deserved reputation as a reformer. He later recalled that in “modern society, all things tend unconsciously toward grand, comprehensive, pervading reforms”. First, Greeley was an advocate of temperance, the movement to abolish the use of alcohol. Perhaps because of his father’s drinking, Greeley made an open pledge of his temperance when he was thirteen years old. He helped found the first temperance club in East Poultney, Vermont and supported the efforts of the Maine Law which prohibited the manufacturing and sale of intoxicating beverages. Second, Greeley was one of the leading Associationists in nineteenth-century America, a group of people who attempted to build a new social and economic order based upon the teachings of Charles Fourier. According to Greeley, Fourierism was “the most natural thing in the world for a properly civilized and Christianized society – the very best to which all the Progress of the last century has tended by a natural law.” Throughout the 1840s, Greeley used the columns of the Tribune to spread the Associationist Gospel. He became president of the American Union of Associationists, and was personally involved in Fourierite communities in Indiana, Illinois, and New Jersey. Third, Greeley supported the movement for land reform aimed at increasing opportunities for individual proprietorships. He argued that the principles of the National Reform Association (founded by New York radical George Henry Evans in 1844) were “the best that can be devised”. Greeley delivered a speech before the New York Young Men’s National Reform Association and attended another convention of land reformers in 1845.[2]

Although he was not an abolitionist, Greeley moved steadily towards a free soil, antislavery position. As a Whig, Greeley naturally opposed the program of “Manifest Destiny” undertaken by the Young American elements in the Democratic Party. By the mid-1840s, he was a firm opponent of the expansion of slavery though he did not move into the Liberty Party. He remained a committed Whig, working to move his party in a free soil direction. He opposed the expansionist efforts of the Democratic Administration of James Knox Polk. Greeley supported the Wilmot Proviso of 1846, which called for the prohibition of slavery in any territory acquired during the war with Mexico. In January 1848, Greeley believed fully that “Human slavery is at deadly feud with the common law, the common sense, and the conscience of mankind.”[3]

As a committed free soiler in the 1840s, Horace Greeley moved easily into the Republican Party. In fact, he played an increasingly visible role as the party formed on a local and national level in the mid-1850s. The initial spark that ignited the Republican Party was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Antislavery Northerners were indignant that this measure of Illinois Democrat Stephen Arnold Douglas, which permitted popular sovereignty for the new territories, overturned the Missouri Compromise. Greeley considered the Kansas-Nebraska Act “a desperate struggle of Freedom against Slavery” . Greeley even suggested the name for the new party as it formed in places like Wisconsin and Michigan. In his native New York, he supported fusion efforts of antislavery Whigs, free soil Democrats, Liberty party and prohibitionists. Yet he resisted Republican efforts to entice anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant Know-Nothings into the party. On the national level, Greeley attended the meeting of Republicans in 1856 in Pittsburgh. The New York Tribune became one of the most influential Republican voices in the nation. With the Whig Party defunct, Greeley threw his editorial support to Republican John Charles Frémont in the election of 1856.[4]

His position as editor of the New York Tribune and as one of the leading Republicans in the most populous state in the North meant that Horace Greeley would play a leading role in the politics of the Civil War. During the secession crisis, Greeley and the Tribune became associated with a view called “peaceable secession,” the idea that the North should allow the disunionist South to depart in peace. On December 17, 1860, Greeley editorialized: “For our own part, while we deny the right of slaveholders to hold slaves against the will of the latter, we cannot see how twenty millions of people can rightfully hold ten, or even five, in a detested union with them, by military force.” After some vacillation, Greeley joined other Republicans by late winter in denouncing the secession of the Lower South states. He urged Lincoln not to compromise on the critical issue of the non-expansion of slavery, the central plank in the Republican platform.[5]

During the war years, Lincoln joined those Radical Republicans who urged a more vigorous prosecution of the war and believed that the war’s aims should include emancipation and the final destruction of slavery. As a Radical, Greeley’s relationship with Lincoln was ambivalent. At times, he was critical of Lincoln, arguing that his political and military leadership was mediocre. What set Greeley and the Radicals apart in the early years of the Civil War was their view on emancipation. At a lecture held at the Smithsonian Institution in 1862 with a clearly discomforted Lincoln in attendance, Greeley called for an end to slavery. In 1863, he appeared at an antislavery meeting at Cooper Union in New York with famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. When Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, Greeley was overjoyed. “It is the beginning of the end of the Rebellion,” the Tribune editorialized, “the beginning of the new life of the nation. GOD BLESS ABRAHAM LINCOLN!” Not surprisingly, Greeley was critical of those New Yorkers involved in the violent and racist draft riots of July 1863.[6]

Greeley is also important to Civil War history for his involvement with peace efforts. He was one of the leading participants in the Niagara Peace Conference of 1864. Learning that Confederate diplomats interested in peace negotiations were in Canada, Greeley referred the matter to Lincoln who then sent the editor to Niagara Falls to meet with these Confederates upon the conditions of a restoration of the Union and the abolition of slavery. These negotiations proved abortive, though Greeley until the end of the war continued to demonstrate an interest in a negotiated peace.

During the period of presidential reconstruction (1865-1867), Horace Greeley remained a Radical Republican. He insisted that freedom and equal rights for African-Americans had to be the cornerstone of any Reconstruction effort. He parted ways with President Johnson after Johnson vetoed the Freedman’s Bureau Bill and a civil rights bill. He supported Johnson’s impeachment and continued to urge black suffrage. At the same time, Greeley was behind efforts to pardon Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

For all his efforts on behalf of Radical Reconstruction, Greeley remained a classical liberal in his reluctance to use the power of the state to ensure equal rights for African-Americans. He was uneasy with proposed plans to confiscate land in the south for freed African-Americans. He was alienated by the radical tenor of labor activism after the Civil War. Greeley was in fact adverse to any class view of the labor situation and persisted in his belief in class harmony and free labor mobility. Characteristically, Greeley placed his faith for labor in cooperative movements. His own retreat from radicalism was embodied in his involvement with the Liberal Republican movement. This was a splinter movement of the Republican Party that supported universal amnesty, tariff reform, civil service reform, and opposition to the Grant Administration. At their national convention held in Cincinnati in May 1872, Horace Greeley was nominated for president. Lacking a viable candidate with national appeal, the Democratic Party also endorsed Greeley for president in 1872. This made the Tribune editor the first person to be nominated for president by two different parties.

Greeley was soundly beaten by Grant in the fall elections. Grant won by a popular majority of over 760,000, a 56% margin that was the greatest of any presidential candidate between 1828 and 1904. Defeated and embittered politically, suffering from the recent loss of his wife Molly, and ill himself, Horace Greeley died on November 29, 1872.

Horace Greeley

- [1] New York Tribune, August 23, 1862.

- [2] Mitchell Snay, Horace Greeley and the Politics of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011), 65; Ibid., 68; Ibid., 74.

- [3] Ibid., 90.

- [4] Ibid., 115; Founded in 1847 the Free Soil Party was active in the elections of 1848 and 1852. Its slogan was “free soil, free speech, free labor and free men” and it’s purpose was to oppose the expansion of slavery in the western territories arguing that free men on free soil was a system superior to slavery. The party was absorbed by the Republicans in 1854; The Know-Nothing movement was active from 1854-1856 striving to curb Irish Catholic immigration and naturalization for fears the republican values of the country would be overwhelmed by Catholic immigrants. The movement experienced little success and by 1860 was no longer a force in American politics. Its name comes from the response members were to give if asked about the movement “I know nothing.”

- [5] New York Tribune, December 17, 1860.

- [6] Snay, Horace Greeley, 142

If you can read only one book:

Snay, Mitchell. Horace Greeley and the Politics of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011).

Books:

Van Deusen, Glyndon. Horace Greeley: Nineteenth Century Crusader. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1953.

Tuchinsky, Adam-Max. Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune: Civil War Era Socialism and the Crisis of Free Labor. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Williams, Robert. Horace Greeley: Champion of Freedom. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.