The Battle of Five Forks

by Edward S. Alexander

The Battle of Five Forks marked the largest single engagement in the last offensive (March 29 to April 2, 1865) of the Petersburg campaign. At the start of the offensive Grant’s forces numbered around 120,000 while Lee had around 50,000 men. Continuing his strategy of trying to outflank Lee’s entrenched troops in the Richmond-Petersburg lines, Grant launched the Army of the Potomac into motion on the morning of March 29, 1865 Learning of the new threat to his right flank, Lee began to gather those reserves he could spare, sending troops to oppose the Federal advance, and the fighting started almost immediately with a small union victory at the Battle of Lewis Farm. In bad weather, the Confederates gathered in a position south of the South Side Railroad, the last supply line into Petersburg at a crossroads called Five Forks and Union forces advanced northwards towards them. Cavalry skirmishing took place on March 30 while the Confederate forces went into position at Five Forks. On March 31 Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee advanced with a combined force of infantry and cavalry against the Federal forces and fought at the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House. The Confederates pushed the federal forces back until they were able to form and hold the line just north of the town, a tactical victory for the Confederates. At the same time as Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee fought this action a separate Confederate force under Brigadier General Samuel McGowan left the entrenchments defending Petersburg and attacked Union forces four miles northeast of the action at Dinwiddie Court House. In the Battle of White Oak Road three Confederate brigades routed two Union divisions but were unable to follow up this success because of a swollen river blocked organized pursuit. McGowan withdrew to his starting position and then, pressed by Federal reinforcements withdrew all the way back to the Confederate entrenchments from which they had started. Despite their initial setback in the morning, the Federals success on the White Oak Road that evening now isolated Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee’s divisions to the south above Dinwiddie Court House. Cut off from support and direct communications, Pickett decided to withdraw early the next morning. On the morning of April 1 Pickett’s men lined the White Oak Road behind hastily constructed fortifications, along a front of nearly two miles, centered on crossroads at Five Forks. Cavalry under Colonel Thomas Munford protected their left flank which cavalry under Fitzhugh Lee protected the right. The General Sheridan, commanding the Union force, devised a plan of battle called Union cavalry to attack on the Confederate right and center to hold those forces in place while General Gouverneur Warren’ V Corps attacked the Confederate left. As the attack commenced Colonel Munford sent couriers to alert Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee. They could not be found. They were in fact having lunch with General Thomas Rosser, under the impression that the Union forces were not advancing. The three generals dined for several hours on shad, a local seasonal fish. They had failed to inform anyone of their location and the shad bake resulted in a lack of coordination between the various infantry, cavalry, and artillery commands which doomed any chance of a successful repulse of the gathering Union force. Fitzhugh Lee afterward claimed that an acoustic shadow prevented them from hearing the battle. Only Rosser publicly admitted to their feast. Warren’s V Corps attacked around 4:00 p.m. Missing their mark which was the left flank of the Confederate forces, Warren’s men swept entirely around the Confederates taking up a position in their rear and the Confederate forces began to retreat. General George Custer commanding the Union cavalry on the Confederate right attempted to sweep around their flank as well to trap the retreating Confederates but was stopped by Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry. This allowed those who fled from Five Forks—Pickett among them—to use a narrow road leading northwest across the stream as the only available avenue to complete their escape. The battle ended with the Union forces controlling all the roads radiating from Five Forks having suffered 800 casualties to the Confederate 3,000, the majority of whom were captured. Capture of the junction itself was not the purpose of Grant’s offensive. The South Side Railroad remained in Confederate hands at nightfall and Sheridan planned to strike for it the next day. Sheridan relieved Warren of command for acting too slowly. Warren resigned his commission and sought vindication. He was exonerated by a court of enquiry in 1882, unfortunately a few months after his death. On April 2 repeated attacks by Union forces destroyed A.P. Hill’s Corps (Hill was killed) and cut all roads west and south out of Petersburg and captured sections of the South Side Railroad. With this defeat Lee withdrew the Petersburg garrison across the Appomattox River the night of April 2 and planned to link with the Richmond Garrison at Amelia Courthouse. Confederate authorities set about destroying items of military value and the fires meant to prevent tobacco, cotton, and ordnance from falling into Federal hands engulfed larger portions of Richmond’s financial and manufacturing districts. On April 3 Federal forces entered Richmond and Petersburg. Union forces, spearheaded by the Five Forks victors, pursued the retreating Confederates until April 9 when, surrounded on three sides, Lee surrendered his army to Grant at Appomattox.

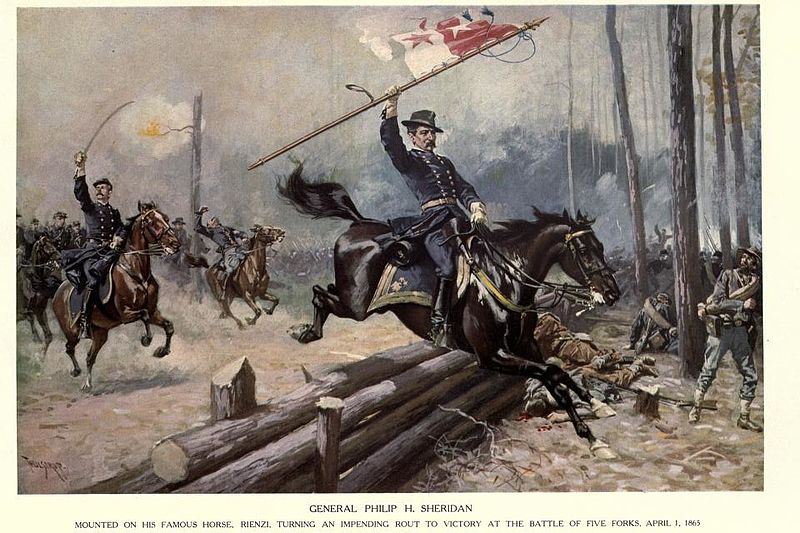

General Philip H. Sheridan at Five Forks

From: Phisterer, Frederick, comp., 6 vols. New York in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 to 1865. Albany, J. B. Lyon company, State Printers, 1912, 5: opposite title page.

The Battle of Five Forks marked the largest single engagement in the last offensive (March 29 to April 2, 1865) of the Petersburg campaign. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant began his efforts the previous June to capture the city of Petersburg, the supply hub located twenty miles south of the Confederate capital at Richmond. For the next nine-and-a-half months, the armies under Grant and General Robert E. Lee opposed each other along a growing front eventually extending forty miles around the cities. After employing a variety of methods to capture either city, destroy Lee’s army, or isolate all three from the rest of the Confederacy, the Union army settled into winter camps at distances ranging from hundreds of yards to several miles from their foe.

During the campaign, Grant left the tactics to Major General George Gordon Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, and his subordinates. Though stymied from their objectives in 1864, Meade’s army managed to pin Lee’s army for the rest of the year into their protective earthworks surrounding the two cities while Union forces elsewhere carved swaths of destruction through the remaining Confederate-held territory to the south.

In the spring of 1865, Grant intended to bring Major General Philip Henry Sheridan’s independent cavalry force from the Shenandoah Valley to Petersburg and send them at the head of a mobile column past the right flank of Lee’s entrenched army. Sheridan had three supply lines as his objective—the Boydton Plank Road, the South Side Railroad, and the Richmond & Danville Railroad. While Sheridan struck at the Confederate logistics, Army of the Potomac infantry would screen their operations from Lee’s interference.

Lee’s army failed on March 25 to regain the initiative and cut the military railroad that Union engineers laid around the city to keep the besieging troops supplied. Undeterred by this bold Confederate attack at Fort Stedman, Grant pushed forward with his planned offensive. He instructed Major General Edward Otho Cresap Ord to bring three divisions from outside of Richmond and at Bermuda Hundred to Petersburg. This freed more of Meade’s army for maneuver. Including the force Ord left behind under Major General Godfrey Weitzel, around 120,000 Union soldiers would be available for operations against Richmond and Petersburg. Lee’s army numbered around 50,000 at this point.

The Army of the Potomac launched into motion on the morning of March 29, 1865. Relieved by Ord’s men, Major General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys moved the II Corps south across Hatcher’s Run to provide flank protection for Major General Gouverneur Kemble Warren’s V Corps who marched south, then west, for the Boydton Plank Road. Sheridan’s cavalry meanwhile aimed for Dinwiddie Court House, further down the road, from which point they would ride northwest for the South Side Railroad.

Learning of the threat to his right flank, Lee began to gather those reserves he could spare. He summoned Major General George Edward Pickett’s First Corps division south from Richmond and recalled the cavalry, under his nephew Major General Fitzhugh Lee, back from their scattered winter encampments in the surrounding counties. Lee directed Fitzhugh and Pickett to a position past the Confederate flank to block the Union approach to the South Side Railroad and sent another division south to contest Warren’s advance. Two V Corps regiments marched up the Quaker Road, advanced past the Lewis farmhouse, and ran into the first Confederate brigade sent south to oppose them. After several hours of seesaw fighting, in which Union reinforcements arrived quicker than their Confederate counterparts, the Confederates withdrew from the field, ceding control of the Boydton Plank Road below Hatcher’s Run. They suffered 250 casualties compared to 375 for the Union.

Warren’s tactical victory at Lewis Farm left the South Side Railroad as the only supply line into Petersburg. Sheridan’s cavalry arrived at Dinwiddie Court House, further to the south, that same day without significant incident and intended to strike for the railroad on March 30. Lee knew he must react swiftly to prevent this Union maneuver from trapping his army and decided on twin offensives against Warren and Sheridan. To provide more manpower for the attack, he transferred a significant portion of Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps from their line protecting the Boydton Plank Road in between Hatcher’s Run and the city’s inner defenses. Pickett meanwhile arrived at Petersburg and marched west to join Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry near the Five Forks intersection. Heavy rains on the night of March 29 soaked the Confederates as they marched and continued throughout the next day, suspending operations until March 31.

Grant knew that Lee would heavily contest his offensive, recalling, “These roads were so important to his very existence while he remained in Richmond and Petersburg, and of such vital importance to him even in case of retreat, that he would make most strenuous efforts to defend them.” He therefore left standing orders for the corps commanders to assault the Confederate fortifications in their front at any point they determined had been weakened. After studying various reports, Meade determined to commit the VI and IX Corps to attack on the morning of March 31 but soon postponed the order, instructing his men to remain vigilant and aggressive.[1]

Union and Confederate cavalry skirmished during the late afternoon of March 30 while Pickett’s infantry settled into place around Five Forks. Pickett intended to attack the following morning and relied on the arrival of two additional cavalry divisions under Major Generals Rooney Lee and Thomas Lafayette Rosser on Sheridan’s left flank to tip the scale in his favor. While Colonel Thomas Taylor Munford’s cavalry division guarded the Five Forks intersection, Pickett gathered his infantry around 10 a.m., March 31, and led them to the west side of Chamberlain’s Bed opposite Sheridan’s left flank. Their attack lurched forward four hours later, the cavalry advancing before the infantry supports were in place. Alerted to the danger, Sheridan sent two brigades to contest the Confederate advance.

As Rosser spurred his men toward Fitzgerald’s Ford—the southernmost of the two crossings—they ran into a stout defense. After three hours the Union troopers withdrew a short distance and dug in along a ridge. Pickett’s infantry enjoyed an easier crossing at Danse’s Ford to the north. Sheridan’s reinforcements could not stem the tide as Pickett sent the rest of his force forward, threatening the Union troopers on three sides. The battle continued to favor the Confederates until they ran into the reserve brigades just north of the courthouse. The Union fire provided a rallying point for the battered Union troopers. Pickett prepared to launch another assault in the late afternoon but could not break this final line. Darkness and a Union counterattack brought an end to the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House. Sheridan lost 350 casualties compared to 750 for the Confederates. Meanwhile, a simultaneous, separate battle fought all day four miles to the northeast nullified any tactical advantage gained in what otherwise proved to be Pickett’s most successful day of battlefield leadership in the Civil War.

Displaying his tendency for the offensive whenever possible, Robert E. Lee had ordered four brigades out of their entrenched line along Hatcher’s Run that morning, March 31. Their objective was to drive the V Corps back from the position they gained during the Lewis Farm fight. Lee hoped this attack toward the Boydton Plank Road would combine with Pickett’s to drive the Union columns all the way back to their original starting positions on the morning of March 29. After Lewis Farm, Warren had slowly extended his men west until nearing the intersection of the White Oak Road and Claiborne Road, defended by entrenched Confederates under Lieutenant General Richard Heron Anderson.

On the morning of March 31, Brigadier General Samuel McGowan’s South Carolinians marched west past this intersection formed for an attack. Their target, Brigadier General Romeyn Beck Ayres’ V Corps division, idled to the south awaiting orders. While McGowan carefully aligned his men without detection, three additional Confederate brigades prepared to pitch into Ayres’ front. Brigadier General Samuel Wylie Crawford’s V Corps division rested behind Ayres while Brigadier General Charles Griffin’s three brigades maintained a connection with the II Corps near the Boydton Plank Road-Quaker Road intersection.

Before McGowan’s five regiments reached their starting points, Warren sent Ayres orders to test the Confederate strength along White Oak Road. The Federal infantry advanced forward and drove the southern pickets into their main line before the South Carolinians were in place. Those Confederates who were instructed to cooperate with McGowan’s attack instead counterattacked on their own. Audacity prevailed despite the lacking coordination and the swift charge startled Ayres’ men. The Federals fired a few rounds into the Alabamians and Virginians in their front but soon broke for the rear as the southern infantry closed for a hand-to-hand fight.

McGowan meanwhile now found a perfect opportunity to send his brigade in from the west onto Ayres’ left flank. Crawford’s division hurried into formation to check the attack, but the detritus of Ayres’ crumbled command broke the ranks of their line. Crawford’s command also soon broke and flooded back toward Griffin’s position at the plank road. “The Fifth Corps is eternally damned,” swore Griffin as he watched three southern brigades rout two full divisions. A swollen branch of Gravelly Run cut a deep ravine in front of Griffin, however, and blocked further organized pursuit by McGowan. Several batteries of V Corps artillery also stood poised to deliver a devastating fire should the Confederates continue their attack.[2]

Unwilling to risk significant casualties to his limited force, McGowan called for assistance from the White Oak Road. Warren also requested for reinforcements from Humphreys. Brigadier General Nelson Appleton Miles’s II Corps division advanced northwest from the Rainey house in between McGowan and the main Confederate line. Brigadier General Henry A. Wise’s Virginians simultaneously moved forward to join McGowan and plunged into Miles’s force. Both pulled back a short distance while McGowan reluctantly withdrew back to the first position seized that morning.

Griffin now rapidly pursued the retreating Confederates and forced them all the way back into their own entrenchments. Some Union soldiers advanced all the way to the White Oak Road, west of the Claiborne Road intersection, where the right end of the Confederate line bent back to anchor on Hatcher’s Run. Warren longed to redeem his corps’ suffering reputation with an attack against the southern fortifications but determined the works to be “as complete and as well located as any I had ever been opposed to.” The Battle of White Oak Road ended for the day with approximately 800 casualties suffered by the Confederates and 1,865 among Union forces.[3]

Despite their initial setback in the morning, the ability of the V Corps to gain a foothold on the White Oak Road that evening now isolated Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee’s divisions to the south above Dinwiddie Court House. Cut off from support and direct communications, Pickett decided to withdraw early the next morning. Fitzhugh Lee wished to fall all the way back above Hatcher’s Run to take position protecting the railroad, but instructions arrived from his uncle instructing the Confederates to remain south of the stream. Sheridan meanwhile stewed on his loss. Despite his tactical defeat on March 31, he recognized the opportunity to even the score with Pickett. “This force is in more danger than I am,” he declared. “If I am cut off from the Army of the Potomac, it is cut off from Lee’s army, and not a man in it should ever be allowed to get back to Lee.” The cavalry commander had accomplished what Ulysses S. Grant had desired since Meade’s army locked horns with Lee in the Wilderness the previous May. “We at last have drawn the enemy’s infantry out of its fortifications, and this is our chance to attack it.”[4]

During that 1864 campaign Sheridan had quarreled with Warren and Meade, ultimately requesting and receiving permission to be cut loose from the Army of the Potomac. Sheridan now needed infantry support from that command to engage Pickett on April 1. Grant offered the V Corps, but, like Sheridan, he had felt dissatisfied with Warren’s overall performance, both before and during the campaign. Haunted with worry that Lee’s army would slip away to the west, Grant wanted commanders in place he could trust to act swiftly and press the opponent while all his own strategic pieces fell into place. He detailed a staff officer to Sheridan with authorization to relieve Warren should the V Corps’ movements proceed slowly.

Meanwhile Grant instructed Warren to move at once to Dinwiddie Court House on the night of March 31 to report to Sheridan. The V Corps commander, not realizing the scrutiny under which he was operating, carefully extracted his men from their lines opposite White Oak Road. Some units did not move until 5:00 a.m. the next morning. As the lead brigades marched south along the plank road they found heavy rains had further risen the level of Gravelly Run. Warren deemed the crossing could not be forded and reported that he needed bridges built to continue as ordered. Hoping to avoid further delay, the V Corps received new instructions after crossing the stream to march cross-country to the west and strike the Confederates at Five Forks on their left flank.

General Pickett’s men lined the White Oak Road on the morning of April 1 along a front of nearly two miles, centered on the star-shaped crossroads at Five Forks. Pickett placed Brigadier General Montgomery Dent Corse’s Virginians north of the Gilliam farm as the right flank of his line. Two more Virginia infantry brigades—under Colonel John Mayo and Brigadier General George Hume Steuart continued the line east past the Five Forks intersection. Colonel William Ransom Johnson Pegram scouted for spots along the line with an open front that would allow him to use his artillery. He placed three guns at Five Forks and another three on Corse’s right flank.

Two infantry brigades borrowed from Anderson continued the line to the east of Steuart. Brigadier General William Henry Wallace’s South Carolinians faced south, and Brigadier General Matthew Whitaker Ransom’s North Carolinians took a partially refused position at the end of the line, their left flank bent back to the north. Munford had responsibility of using his cavalry division to watch Pickett’s left flank while Rooney Lee guarded the right. Neither flank was properly anchored on any substantial geographic feature, but the infantry created crude log and earthen breastworks.

Map Courtesy of The American Battlefield Trust

Union cavalry had slowly advanced north from Dinwiddie Court House, lightly skirmishing with the Confederates as they fell back toward Five Forks that morning. As Pickett’s command settled into their position around the intersection, Sheridan developed a battle plan to exploit its weaknesses. He directed his cavalry to dismount and utilize their repeating carbines to engage Pickett’s thin line. With the Confederates immobile behind their hastily constructed fortifications, the V Corps would sweep around their left flank and drive them to the west, away from the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. With that maneuver accomplished, the tracks of the South Side Railroad—Petersburg’s final supply line—would be open to capture.

While Union cavalry popped away at the Confederate front throughout the afternoon, Warren marched his corps into position for the decisive sweeping attack. He instructed Ayres to advance up Gravelly Run Church Road with Crawford on the right and Griffin in reserve. The infantry carefully deployed into position, exercising caution to not be spotted. The delay further incensed Sheridan, who felt Warren was attempting to let the sun go down before the battle could be fought. Impatient at the inactivity, Sheridan directed Brigadier General Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, whose Army of the James cavalry division had just joined the expedition, to sever the fragile connection between the Confederates at Five Forks and the right flank of Anderson’s main line near the Claiborne Road. A small cavalry force picketed the White Oak Road along this four-mile stretch and did not have the strength to oppose Mackenzie’s determined attack.

The blue jacket troopers successfully seized a position near the Crump Road intersection with White Oak Road, but their charge alerted the Confederates to the danger to their flank. A courier brought news of Mackenzie’s attack to Munford, who had responsibility for protecting Pickett’s left. He hurried his command from their camp along Ford’s Road into position east of the angle in the infantry line. Munford afterward claimed that he then saw the V Corps deployment. He sent several couriers to inform Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee of this development, but the staff officers could not find the generals.

Rosser had camped his division along the Nottoway River before the campaign began. He borrowed a seine and caught many shad, a migrating fish. Orders summoning him to Five Forks arrived before he could enjoy the bounty, so Rosser packed the fish on ice and placed it in his ambulance. When the Confederates fell back from Dinwiddie Court House early in the morning on April 1, Rosser asked for a reserve position for his division on the north side of Hatcher’s Run, citing his horses’ need to rest and refit. That request granted, Rosser instructed his cook to begin preparing the shad and invited Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee to join him for lunch. Both major generals believed that Sheridan’s lackluster pursuit from Dinwiddie Court House signaled a suspension of operations and therefore accepted. The trio dined for several hours north of Hatcher’s Run but failed to inform anyone of their location. Lack of coordination between the various infantry, cavalry, and artillery commands doomed the already thin chance of successfully repulsing the gathering Union force.

The V Corps finally completed their arrangements around 4:00 p.m. and marched northward. Their advance almost immediately went astray, to the benefit of the attack but to the downfall of its commander. Sheridan had provided inaccurate information as to the location of the angle in the Confederate line. Warren planned for Ayres to attack in front, holding the Confederates in place while Crawford swept in from the east. The angle in the lines was seven hundred yards further west from where Sheridan specified. Dense vegetation, and the need for secrecy, prevented the V Corps general from properly scouting the position on his own.

Thus, as Crawford’s men piled out of the woods near Gravelly Run Church, they completely missed the Confederate line half a mile to the west and pressed onward across White Oak Road. Munford’s dismounted troopers provided slight resistance, not adequate to repulse the attack but enough to force the Federal infantry to attempt to flank their position rather than to attack in front. Crawford’s division therefore plunged back into the undergrowth and continued northward past White Oak Road. This led them toward Hatcher’s Run but away from their objective. Ayres also did not immediately strike any Confederate infantry but came under artillery fire from the angle as he gained the White Oak Road. He wheeled his men to charge westward while Griffin pushed his division forward to extend Ayres’s right flank, taking the position originally assigned to Crawford.

Warren meanwhile frantically sent couriers to Crawford to correct his stray path. Frustrated by a lack of response, the corps commander rode off after the wayward division, leaving Ayres behind. The Federals struggled through the dense undergrowth on either side of the White Oak Road and suffered under increasingly heavy fire from the angle. After Warren had ridden after Crawford, Sheridan appeared among the V Corps infantry. “Where is my battle-flag!” he shouted. Seizing it from his color sergeant, he stood high in his saddle, waved the banner over his head, and cheered the infantry onward. Ayres also drew his sword and rushed forward, leading his men with fixed bayonets over the earthworks at the angle, seizing a small number of prisoners. Sheridan bounded over behind the infantry and landed among the captives. He ordered them to head for the rear after relinquishing their weapons, declaring, “You’ll never need any more.”[5]

The Union cavalry had meanwhile continued to press the Confederate center and right. Brigadier General Thomas Casimir Devin’s three brigades covered the Confederate front from opposite the angle to Five Forks. Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer’s division meanwhile squared off against Pickett’s Virginians in a fight more even for the Confederates than the lopsided battle now rolling up their left. Pegram’s three artillery pieces at the intersection rapidly fired double rounds of canister at close range as dismounted Union troopers crept within thirty yards of Five Forks. Pegram learned of the pressure in the middle of the line and galloped to the crossroads. He loudly encouraged his cannoneers, “Fire your canister low, men!” A few moments later, the young colonel slumped mortally wounded from his saddle.[6]

The three highest ranking Confederate generals meanwhile continued to enjoy their lunch, oblivious to the combat raging just one mile to the south that was collapsing their line. Fitzhugh Lee afterward claimed that an acoustic shadow prevented them from hearing the battle. Only Rosser publicly admitted to their feast. An oblivious Pickett eventually wondered if there were any developments and sent a courier south toward Five Forks. As the rider crossed Hatcher’s Run, a small portion of Crawford’s division burst through the woods and captured the messenger. Pickett immediately mounted and raced across the stream, arriving at Five Forks just as its defenders crumbled. Lee and Rosser meanwhile stayed north of Hatcher’s Run to guard the wagon train and prevent any Federals from crossing to cut the South Side Railroad one and a half miles to the north.

Though Crawford’s division missed their mark in the initial advance, their movement to the north had placed them in an advantageous position to strike Ford’s Road between Five Forks and Hatcher’s Run. While Devin assailed the Confederates in front and Ayres and Griffin bent in the right, Crawford essentially took a position in rear of the beleaguered defenders with little challenge. The dismounted cavalry soon swarmed up to the makeshift Confederate fortifications and engaged in a vicious, though brief, hand-to-hand struggle. Nearly surrounded on three sides, the remnants of Ransom, Wallace, and Steuart’s brigades streamed along the only open route to the west. Pickett instructed Mayo’s brigade to strike for the South Side Railroad. Portions rallied on Corse’s brigade, which had wheeled to face east because Custer’s cavalry had abandoned their attempt to force the Virginia brigade’s lines. Instead, Custer attempted to swing around the Confederate right flank and complete the trap by gaining the south bank of Hatcher’s Run.

Rooney Lee’s division battled Custer to a standstill, allowing those who fled from Five Forks—Pickett among them—to use a narrow road leading northwest across the stream as the only available avenue to complete their escape. The V Corps meanwhile continued their pursuit, arraying themselves in line to attack Corse’s position. The marshy, wooded terrain hampered their redeployment. Fighting continued along the front until dark, when the Confederates fell back along their only route north. They left behind 3,000 casualties, the majority of which were captured, compared to just over 800 Union losses. By the battle’s end, Union forces had control of all roads radiating from the Five Forks intersection.

Capture of the junction itself was not the purpose of Grant’s offensive. The South Side Railroad remained in Confederate hands at nightfall and Sheridan planned to strike for it the next day. He intended to do so, but without Warren. Using the discretionary orders provided by Grant, Sheridan relieved him of corps command. Warren resigned his military commission in June but spent the rest of his life attempting to restore his reputation. He waited until after Grant’s presidency to apply for a court of inquiry. The court convened in the summer of 1879 and numerous prominent generals, including several Confederates, testified about their role in the battle. The court ruled in Warren’s favor, but their findings were belatedly published. Warren died on August 8, 1882, before his name was publicly cleared on November 21.

Meanwhile, before Warren’s attack at Five Forks had even begun, Meade had sent orders to Major General Horatio Gouverneur Wright, commanding the VI Corps, to attack the Confederate earthworks in his front just southeast of Petersburg the following day. Wright and his generals had scouted the terrain for the past week and developed a plan that utilized Arthur’s Swamp, a marshy stream flowing out of the Confederate lines. This ravine provided physical orientation and cover for Wright’s pre-dawn attack. When news of the victory at Five Forks reached Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters, he amended Meade’s orders and called for an attack all along the lines that night.

Meade and his corps commanders responded, by message, that an immediate assault was impracticable, so Grant agreed to change the orders to attack before daylight on April 2. He expected Sheridan and Griffin to advance from Five Forks to the Southside Railroad, Humphreys’ II Corps to attack the Confederates that remained below Hatcher’s Run, Ord’s three Army of the James divisions to charge the Confederates on the north side of that stream, Wright to advance as previously planned, and Major General John Grubb Parke’s IX Corps to seize the defenses southeast of Petersburg.

Lee meanwhile responded to the defeat at Five Forks by sending Anderson with three infantry brigades from their position near Burgess Mill to a position blocking Sheridan’s direct route to the railroad. This transfer left three brigades in front of Humphreys’ corps and five brigades to oppose Wright and Ord’s six divisions. The Union high command could not be certain of Confederate troop strength behind their entrenchments, however, and veterans in the rank-and-file viewed their orders to attack with a nervous optimism. Ord reported that the terrain his men would have to cross was not conducive for an attack and received amended orders to hold his men in readiness to exploit any success by Wright. Humphreys meanwhile delayed his attack until well after sunrise. Parke attacked first on April 2, capturing the Confederate line where the Jerusalem Plank Road exited the earthworks. Stiff resistance marked by desperate counterattacks throughout the day prevented any further advance into Petersburg. Wright attacked at 4:40 a.m. and broke the Confederate lines at Arthur’s Swamp.

The VI Corps swept to the south during the morning and captured the Confederate line all the way to Hatcher’s Run. Hundreds of Confederate eluded capture by crossing the stream but found themselves on the move once more as the brigades opposing Humphreys fled west along White Oak Road and then north along Claiborne Road to cross Hatcher’s Run. Humphreys sent one division in pursuit and overran the Confederates when they turned to put up a fight that afternoon at Sutherland Station. Sheridan initially planned to follow up the Claiborne Road with the V Corps before returning with the infantry back to Five Forks. Union cavalry made forays toward the South Side Railroad and captured sections of the track west of Sutherland Station. The rest of the II Corps followed the VI Corps as it turned back on Petersburg. Ord had meanwhile sent Major General John Gibbon with two XXIV Corps divisions north through the lines captured by Wright’s attack. Gibbon’s progress was checked until the middle of the afternoon by a desperate defense at Forts Gregg and Whitworth. By late afternoon, the Confederates had lost all ground outside of the Dimmock Line, Petersburg’s immediate defense.

Lee began the morning intending to hold the position at Petersburg, perhaps even driving Sheridan away from Five Forks. He summoned the rest of Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps to Petersburg but knew they would not arrive until the afternoon. A.P. Hill awoke to reports of Parke’s attack. He rode to Lee’s headquarters where he learned his own corps was also under attack. Hill determined to proceed toward his lines, not knowing that the VI Corps assault had already overrun that position. Along his route up Cattail Run, Hill encountered two Union soldiers—Corporal John Watson Mauk and Private Daniel Wolford of the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry—who had swarmed over the lines near the Hart house that morning, struck out on their own to wreck the South Side Railroad, and now returned to find breakfast. Hill demanded that the pair surrender while his lone escort, Sergeant George Washington Tucker, attempted to move his horse forward to shield the general. The two Federals fired and Mauk’s shot struck Hill, killing him instantly.

When Lee learned of Hill’s death and the destruction of his corps, he sent a message to the Confederate government that he planned to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The defense at Fort Gregg bought time for Longstreet’s men to arrive to the Dimmock Line, but Union soldiers had cut all roads west and south out of Petersburg. At nightfall Lee withdrew the Petersburg garrison north across the Appomattox River and planned to link with the Richmond garrison at Amelia Court House. From there they would travel along the Richmond & Danville Railroad to North Carolina and a rendezvous with General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s Confederate army, currently opposing Major General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Union force. The decisive Union victory on April 2 forced a hasty evacuation that hindered logistics along Lee’s route.

Confederate authorities also insisted on destroying items of military value and the fires meant to prevent tobacco, cotton, and ordnance from falling into Federal hands engulfed larger portions of Richmond’s financial and manufacturing districts. The next morning, April 3, Union soldiers crept toward the vacated Confederate defenses outside Petersburg and Richmond before racing forward to capture the long-awaited prize. Sheridan’s position on the South Side Railroad meanwhile provided an inside track for the race to Burkeville Junction, through which Lee had to pass while following the Richmond & Danville Railroad. Grant’s swift chase, spearheaded by the Five Forks victors, blocked the Confederate path from Amelia Court House and forced Lee to march even further to the west. Union pursuit continued until April 9 when, surrounded on three sides, Lee surrendered his army to Grant at Appomattox.

****

- [1] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885-1886), 2: 602.

- [2] Joshua L. Chamberlain, The Passing of the Armies: An Account of the Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, Based upon Personal Reminiscences of the Fifth Army Corps (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915), 72.

- [3] Gouverneur K. Warren to George D. Ruggles, February 21, 1865, United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 33, part 2, p. 300 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 33, pt. 2, 300).

- [4] Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (New York: The Century Co., 1897), 432.

- [5] Ibid., 439-40.

- [6] Peter S. Carmichael, Lee’s Young Artillerist: William R.J. Pegram (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 1995), 163.

If you can read only one book:

McCarthy, Michael J. Confederate Waterloo: The Battle of Five Forks, April 1, 1865, and the Controversy that Brought Down a General. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017.

Books:

Alexander, Edward S. Dawn of Victory: Breakthrough at Petersburg, March 25-April 2, 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2015.

Bearss, Ed and Chris Calkins. The Battle of Five Forks. Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, 1985.

Bearss, Edwin C. and Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign, Volume 2: The Western Front Battles, September 1864-April 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014.

Calkins, Chris. The Appomattox Campaign, March 29-April 9, 1865. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997.

————. History and Tour Guide of Five Forks, Hatcher’s Run and Namozine Church. Columbus, OH: Blue & Gray Magazine, 2003.

Greene, A. Wilson. The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2000.

Hess, Earl J. In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865. Boston, MA: Little Brown, 1991.

Organizations:

Petersburg National Battlefield Virginia

Petersburg National Battlefield preserves 1,215 acres of the Five Forks battlefield, including a visitor contact station and museum. A five-stop driving tour and eight miles of hiking trails cover many of the key locations from the engagement on April 1, 1865. The site of the shad bake is not publicly accessible.

The park grounds are open every day of the year except for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day from 8:00 a.m. until dusk. The gate to the Visitor Contact Station opens at 8:00 a.m. and closes at 5:00 p.m. The Visitor Contact Station is open from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

The Five Forks Battlefield Visitor Contact Station’s address is 9840 Courthouse Road, Dinwiddie, VA 23841, 804-469-4093.

Petersburg Battlefields Foundation

The Petersburg Battlefields Foundation’s vision is to inspire and educate the public about the Petersburg Campaign of the Civil War. Their mission is to lead a regional initiative to preserve, interpret, and promote the Campaign’s diverse cultural, natural, and historic resources. Part of their activities include maintenance projects on the Five Forks battlefield.

Contact Info P.O. Box 1975, Prince George, VA 23875, info@petebattlefields.org.

The American Battlefield Trust

The premiere private preservation organization, the Civil War Trust has actively preserved and interpreted many key sites in Dinwiddie County pertaining to the final battles around Petersburg.

The Civil War Trust has preserved 387 acres at Hatcher’s Run, 903 acres at White Oak Road, 419 acres at Five Forks, and 407 acres of the Petersburg Breakthrough Battlefield. Interpretive walking trails allow visitors to tour Confederate entrenchments at Hatcher’s Run and along White Oak Road. The Petersburg Battlefields Trail, in partnership with Petersburg National Battlefield and Pamplin Historical Park, provides interpreted access to the ground where the VI Corps began their decisive charge on the morning of April 2, 1865. The site of A.P. Hill’s death is also preserved by the Civil War Trust and marked with a small granite monument.

Pamplin Historical Park

Located on the site of the April 2, 1865 breakthrough, the battle that ended the Petersburg Campaign and led to the evacuation of the Confederate capital at Richmond, the Park’s 424 acres include four award-winning museums, four antebellum homes, living history venues, and shopping facilities. The Park is in Dinwiddie county, near Petersburg, Virginia.

The award-winning National Museum of the Civil War Soldier forms the Park’s centerpiece. Here, the story of the 3 million common soldiers who fought in America's bloodiest conflict is told using the latest museum technology. An impressive artifact collection is set amidst lifelike settings.

The Park is open daily from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

The park address is 6125 Boydton Plank Road, North Dinwiddie, VA 23803, 804-861- 2408.

Web Resources:

The American Battlefield Trust provides maps, articles, and videos pertaining to Five Forks and other battles and sites around Petersburg.

This is the Encyclopedia of Virginia’s entry on the Battle of Forks.

This is an article and bibliography on the battle that is part of an impressive website exclusively devoted to the study of the full Petersburg campaign.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.