The Hampton Roads Peace Conference

by James B. Conroy

The Hampton Roads Peace Conference culminated in a meeting between President Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward with three Confederate commissioners with the aim of negotiating the end of the Civil War. It was held aboard the presidential steamboat River Queen on Friday, February 3, 1865 at Hampton Roads Virginia. Francis Preston Blair initiated the process in late December, passing through union lines with the knowledge of President Lincoln to meet with Jefferson Davis in Richmond. Blair proposed to Davis that Lee would retreat from Richmond into Mexico, pursued by Grant and the two armies would join together to fight the Emperor of Mexico. Reunion would follow, the South would abandon slavery for a chance to look Mexico and Davis would become President of Mexico. Davis endorsed this bizarre plan offering to send envoys to Lincoln to negotiate peace. Davis sent three commissioners who were members of a group trying to end the war. If they bought breathing room for the Confederacy Davis would take it, if they failed, they and their compatriots would be discredited. The Confederate commissioners duly moved through their lines and met with Grant at City Point. On February 2 Lincoln slipped out of Washington and met with the Confederate commissioners the next morning. Lincoln made it clear he had no interest in the idea of invading Mexico but offered in return for laying down of Confederate arms the lives, liberty, and property of all southerners and an agreeable postwar order. The northerners revealed that the Thirteenth Amendment freeing the slaves had passed in Congress and now awaited ratification of 2/3rds of the states. If the Confederates rejoined the union immediately, with 11 states, they could block ratification. Lincoln pointed out that Congress controlled when the Confederate states could rejoin the union. He also stated that he was in favor of compensation for emancipated slaves, though again Congress would decide that as well. At the heart of the negotiation was Lincoln’s demand for immediate reunion which Davis refused to contemplate. Though ideas had been discussed there was no concrete proposal for peace. The Confederate commissioners returned to Richmond: Returning to Washington, Seward announced that the peace talks had failed, but Lincoln continued to work on a formal peace offer involving immediate reunion, ratification of the 13th Amendment, return of confiscated property except slaves, and compensation to be paid for freed slaves. Lincoln took his plan to his cabinet where he was unanimously rebuffed, and where he abandoned any further attempt to reach a peaceful settlement of the war. As the sure defeat of the Confederacy came closer day by day after the conference, Confederate leaders discussed reopening negotiations for peace along the lines discussed at the Hampton Roads Peace Conference, but no one was willing to take responsibility and act. Within a dozen weeks after the Hampton Roads conference, the Carolinas were looted, the better parts of Columbia and Richmond were burned, the Confederacy’s leaders were jailed, Davis was captured in Georgia with a thinly escorted band of frightened women and children, and Lincoln was dead. So were 10,000 Union and Confederate soldiers who were killed fighting in the last battles as the Army of Northern Virginia retreated towards it’s end at Appomattox Courthouse. Years would pass before the occupied Southern states were admitted back into the Union.

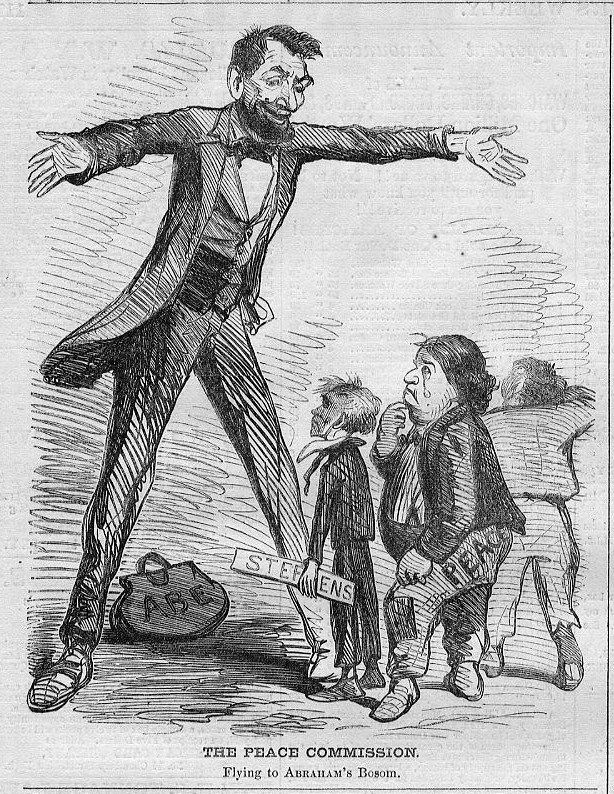

“Flying to Abraham’s Bosom,” which appeared in the February 18, 1865 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

On Friday, February 3, 1865, on a day more like spring than winter, President Abraham Lincoln and his charming Secretary of State William Henry Seward welcomed three Southern friends to the presidential steamboat River Queen in search of a peaceful way to end the Civil War. The three Southern doves were distinguished men with close ties to their hosts. Alexander Hamilton Stephens of Georgia, the floridly eloquent Vice President of the Confederate States of America, had been Lincoln’s friend and colleague in the congress of 1847-49 and a fellow opponent of the Mexican War. Virginia’s accomplished Senator Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter had enjoyed a 12-year friendship with Seward in the old Senate. The brilliant Alabamian John Archibald Campbell, the Confederacy’s Assistant Secretary of War, had attended Lincoln’s inauguration as a justice of the United States Supreme Court and had worked hard with Seward to try to stop the war before it started. They had come to Lincoln now with a slim hope of ending it, and the origins of their mission were little short of bizarre.[1]

Though the Confederacy was all but beaten, it was capable of fighting on, and Lincoln had been struggling with a dilemma. He wanted to end the war quickly, peacefully if possible, not only to save lives, money, and property but also to build a stronger foundation for reconstruction. If the Confederacy could be persuaded to return to the Union voluntarily, enticed by reasonable concessions, the stage would be set for a more amicable, productive future than a military conquest could produce. But conciliation implied negotiation, and to negotiate with the Confederacy would be tantamount to conceding its legitimacy, betraying, as Lincoln thought, the very principle that the North had been fighting for. The point seemed moot in any case, for it could hardly be plainer that the intractable Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, would negotiate for nothing less than the Confederacy’s independence, however hopeless its cause. The Northern Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, confided the conundrum to his diary: Lincoln wanted peace, but “who will he treat with, or how commence the work?”[2]

The work commenced with Francis Preston Blair, the aged patriarch of Blair House, across the street from the White House, and a Maryland country estate called Silver Spring. A wealthy newspaper publisher and an influential Washingtonian since President Andrew Jackson had summoned him north to join his kitchen cabinet, Blair was in a unique position to broker a deal if a deal could be had. Virginia born, and Kentucky bred but as fierce a Southern Unionist as Jackson had ever been, Blair was a senior counselor to Lincoln and a father figure to Davis, having mentored his career until Davis left the Senate when his native Mississippi seceded.

At Christmastime in 1864, Blair walked across Pennsylvania Avenue and began to tell the President that he wanted to go to Richmond to present his old friend Davis a plan to end the war, abolish slavery, avert the Confederacy’s defeat, and restore her to the Union in one astonishing swoop. Lincoln cut him off before he could get it out of his mouth. If he wanted to go to Richmond, he could have a pass through the Union lines, but he would have no authority whatsoever to speak for the president, who did not want to know who he would see there, let alone what he would say—today we would call it plausible deniability.

Passing through Union headquarters at City Point, Virginia on his way to see Davis, Blair confided his plan to General Ulysses S. Grant, who would soon play a crafty role in advancing it; but any hope of secrecy disappeared when Blair’s presence in the Confederate capital exploded in the Richmond press and in Washington too. Something big was clearly happening, and the war-weary citizens of Richmond were speaking of little else when the Davises greeted Blair at their door.

“Oh you rascal,” Mrs. Davis said, “I am overjoyed to see you.”[3] His rascality unfolded after dinner as he laid out his plan to her husband. The Confederacy had lost the war but could still win an honorable peace. Skipping negotiations, a political impossibility in both capitals, Lincoln and Davis would endorse a secret plan. Robert E. Lee, dug in against Grant at Petersburg, Virginia, would lead his army southwest in a bogus retreat. Grant would follow Lee in hot pursuit, but not so hot as to catch him until he crossed the Rio Grande and picked a fight with the French army propping up the Austrian Archduke Maximilian, installed by Napoleon III as Emperor of Mexico in 1864 while the Monroe Doctrine’s proponents were otherwise engaged. With one American army attacked by a foreign foe, the other would jump in on its side, a scenario that Seward had envisioned in 1861—the provocation of a war with a foreign power to draw the seceded states back into the Uni9on in solidarity with their fellow Americans. [4] Together they would crush the French and embrace on the nostalgic fields of the Mexican War, reunion would follow as night the day, and the Confederacy would abandon slavery for a chance to loot Mexico, which Davis would rule as governor.

Instead of laughing off Blair’s pipedream, Davis purported to embrace it, and began an exchange of letters funneled through Blair in a 19th century form of shuttle diplomacy. Under heavy domestic pressure to negotiate, Davis offered to send envoys to Lincoln to endeavor to end the war for the good of “the two countries,” and Lincoln replied with an offer to receive emissaries restoring peace to “our one common country,” whether sent by Davis or “any other influential person now resisting the national authority…”[5] Lincoln had cause to believe that such persons might wrest power from their president. In Richmond, Blair had met with old friends associated with what Davis called The Cabal, public men who knew the war was lost and wanted a way out. Blair reported their aspirations to Lincoln, who surely hoped to encourage them.

Late in January 1865, after Blair’s second trip to Richmond, Davis sent three Peace Commissioners to Lincoln to discuss the Mexican plan (which Davis assumed came from Lincoln and Seward), or any other route to peace, conditioned on just one non-negotiable demand, an independent Confederacy. As Davis well knew, had Lincoln been able to choose only one condition to reject, that would have been the one. But Davis had a plan of his own. In his unforgiving view, all three of the envoys he chose to send to Lincoln—Vice President Stephens, Senator Hunter, and Judge John Archibald Campbell—were charter members of The Cabal. If they managed to leverage a truce out of Lincoln’s hope for peace, Davis would take the breathing room. If not, their mission would fail abjectly, discrediting them and their supporters, and that would be satisfactory too.

A joyful pandemonium erupted in the trenches beneath Petersburg when the three Confederate peace commissioners presented themselves at the Union lines and announced that they were on their way to Washington to end the war. General Grant, they said, was expecting them. White flags of truce sprung up on both sides; men and boys in blue and gray traded newspapers, jokes, and humble goods; and the jubilant word went forth that the war was as good as over. But Grant was in North Carolina for consultations, and his second in command wired a request for instructions to the War Department. Lincoln’s Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton, no friend of negotiations or Grant, was quick to respond. Washington knew nothing about any peace commissioners. They were to be kept on their own side of the lines unless and until the president ordered otherwise.

Two days later, Grant returned to City Point and waived them across his lines as if Stanton’s order did not exist. Grant later said he had been unaware of it, an idea as ludicrous as Blair’s Mexican fantasy. The general welcomed the rebel envoys to his cabin; threw them a sumptuous, well-oiled dinner on his steamboat, Mary Martin with 50 of his senior officers; gave them the run of City Point while he waited for orders to pass them through to Washington or not; helped them find the words to get them past Major Thomas Thompson Eckert, a Stanton aide sent by Lincoln to vet their intentions; apparently interfered with Eckert’s telegrams to Washington; and phrased and timed his own telegrams to help get the Southerners through to Lincoln, using ways and means that can fairly be called disingenuous. Grant had seen enough of war.

Lincoln resorted to deception too. On the day the Confederate dignitaries crossed Grant’s lines, the House of Representatives was to vote on the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, banning slavery. The chances for the bill’s success were too close to call, despite the Administration’s campaign to pressure and reward enough Democrats to support it. Lincoln was writing to Seward, sending him to meet the commissioners at Fort Monroe, the Union stronghold at Hampton Roads, Virginia, to determine whether they were ready for reunion and to turn them back if they were not, when a messenger brought a note from the House bill’s floor manager. The floor was rife with rumors that rebel peace envoys were in Washington or on their way, it said, and the vote would be lost unless Lincoln could attest to the contrary. If the Confederacy’s leaders were considering reunion, hardly any Democrats would discourage them by banning slavery.

Honest Abe scrawled a message on the note and sent it back up Capitol Hill: “So far as I know, there are no peace commissioners in the city or likely to be in it. A. Lincoln.”[6] Moments later, he finished sending Seward to meet them at Hampton Roads. Later that day, the House endorsed abolition by a margin of two votes, literally as the peace commissioners were crossing Grant’s lines. Far from sheepish about misleading Congress, Lincoln chuckled over it later.

As the peace commissioners waited at City Point to learn whether Lincoln would see them, Grant sent a brilliantly crafted wire to Washington. Following the chain of command, he addressed it to Stanton, knowing that Lincoln would see it, as he monitored all of Grant’s wires. The general had met with the peace commissioners, it said, and was sure “that their intentions are good and their desire sincere to restore peace and union.… I fear now they’re going back without any expression from any one in authority will have a bad influence.” He was sorry that the President “cannot have an interview” with them, since their communications to Grant were “all that the President’s instructions contemplated” on their willingness for reunion.[7] Lincoln’s reply soon reached the general, who joyfully read it aloud to the peace commissioners. “Say to the gentlemen I will meet them personally at Fortress Monroe as soon as I can get there.”[8]

Hoping to avoid publicity -- counterproductive to success and unwelcome in the event of failure -- Lincoln slipped quietly out of the White House on Thursday morning, February 2, and traveled south to Hampton Roads by steamboat, accompanied only by an Irish-born valet. Predictably enough, secrecy broke down immediately, and before the day was out, peace talks were headline news, as fire breathing newspapermen and politicians on both sides condemned the very notion of compromise while Grant and Lee, common soldiers, and common people prayed for peace.

At sunset on Thursday evening, the peace commissioners arrived at Hampton Roads on the Mary Martin. Seward was already there on the River Queen, the splendidly appointed Air Force One of her day. When the Mary Martin arrived, she tied up alongside the River Queen. Awaiting Lincoln’s arrival, Seward kept his distance from Stephens, Hunter, and Campbell, all of them old friends of the antebellum years, but sent them a welcoming gift—three bottles of good whisky.

When the president reached Hampton Roads, word was sent over to the commissioners that the conference would convene in the morning. As Lincoln and Seward took their rest on the River Queen and the commissioners on the Mary Martin, a reporter set the scene: “Peacefully and fraternally these little steamers lay side by side on the placid waters of the river.”[9]

A warm sun was shining on February 3, 1865 as the Southerners were shown to the intimate floating drawing room on the River Queen’s upper deck. In the gravity of the moment, the paddle wheeler’s Victorian splendors were probably lost on the anxious peace commissioners, who did not have long to admire them before Lincoln and Seward walked in and offered their hands to their enemies.

No introductions were necessary. Every man in the room had worked with every other, with the possible exception of Lincoln and Hunter. They had both been in the congress of 1847-49 but the Virginian had served in the Senate while Lincoln had served in the House.

Having parted as friends, it was awkward to reunite as foes after almost four years of brutal war, but the tension abated a bit when Stephens greeted Lincoln with heartfelt warmth and Lincoln replied in kind. Almost freakishly small at less than 100 pounds, the Confederate Vice President addressed his host in his childlike voice as Mr. President, and Lincoln called him Stephens, a familiar form of address that neither recognized his title nor snubbed it.

Lincoln was astonished by the weight that Stephens seemed to have gained, until the sickly little Georgian unwound several scarves and a shawl and struggled out of a ponderous gray overcoat of homespun Southern wool. As the tiny man shed his wrappings, Lincoln took a chance on an icebreaking joke: He had never seen so small an ear emerge from so much husk. Happily for diplomacy, Stephens led the laughter. With the ice duly broken, Lincoln and Stephens reminisced, Seward and Hunter rekindled their friendship, and even the dour John Campbell struck a diplomatic pose.

A black navy steward served refreshments and cigars as the guardians of slavery and the champions of abolition reminisced about old times. Seward asked to be remembered to Mr. Davis, a friend as well as an adversary before the war. Stephens spoke fondly of The Young Indians, a group of upstart Congressmen including him and Lincoln who had helped make Zachary Taylor President in 1848. Campbell thought that Stephens was recalling their old friendship more brightly than Lincoln was. Cigar smoke filled the air as everyone but Lincoln enjoyed the common vice, and so did a bittersweet nostalgia that no one seemed eager to spoil.

It was Stephens who called the meeting to order with some seemingly well-chosen words, halfway down the road to reconciliation. “Well, Mr. President,” he said, was there no way to put an end to the present troubles and restore the good feelings that existed in those days between the different states and sections of the country? Lincoln’s reply was sharp and unequivocal. There was only one way he knew of, he said, and that was for those who were resisting the national authority to stop.[10] The laughter had come to an end.

Stephens brought up Blair’s joint invasion of Mexico, and Lincoln made it clear that he was not interested. He was interested in submission, and he took a hard line. There would be no truce to accommodate negotiations. The Confederacy must put down its arms and accept reunion first. [11]

The commissioners wished to know where that would leave them, and what would be left to negotiate. The model of a practical man with no illusions about the South’s military fate, Campbell asked Lincoln a question: Supposing that the Union were reconstructed with the Confederate States’ assent, how would the reconstruction be accomplished? Lincoln answered it as simply as Campbell asked it: By disbanding their armies, he said, and letting the federal authorities resume their rightful roles.[12] As the conversation went on, he coupled his demands with warnings. If nothing concentrates the mind like the prospect of hanging, his guests were paying attention when Lincoln made it clear that harder men than he were demanding the ultimate punishment for the senior rebel leaders.[13]

But as the meeting progressed, the Northerners stopped thumping their chests and laid carrots next to sticks to coax the commissioners home. Without negotiating per se, they put four enticements for their guests on the table, none of them inconsiderable; their lives, their liberty, their property, and an agreeable postwar order.

Ironically, it was on the issue of slavery, the issue at the heart of the war, the fundamental issue of American politics, where the Northerners had room to maneuver. Lincoln would take no backward steps on slavery, he said, but stepping forward was something else again. He would not change the Emancipation Proclamation in the slightest particular. The point was what it meant and would mean after the war. Was it a purely military measure or did it have the force of law, with permanent consequences? Did it operate only in the parts of the South that Union forces had already taken or was it effective everywhere? These were legal issues. How judges would decide them he did not pretend to know. He supposed they would be tested when someone took a slave from one place to another and the issue was raised in court. But he did not stop there. In his own opinion, he said, the Emancipation Proclamation had only freed the slaves in places under Union occupation, though the courts might decide otherwise.[14]

Judge Campbell would have gotten the message even if the other two commissioners (both of them lawyers) had not. He had sat on the Supreme Court that decided that a slave was not made free when taken into free territory. The Dred Scott decision was still the law of the land. The Northerners’ enticement was plain, whether they meant it or not. Unlike the coming battles to be fought on Southern soil, the South could win battles to be fought in Southern courts.

Then Seward revealed the morning’s surprise— the House had just endorsed a Constitutional Amendment banning slavery, which would free the slaves everywhere, whether under the Union army’s control or not, if two thirds of the states ratified it. Campbell asked Seward what significance he attached to it. Steward’s reply would have been astonishing had his cunning not been as famous as his charm. “Not a great deal,” he said. There were 36 states in the Union (the whole Union), any ten of which could block the Amendment’s ratification.[15] He did not insult the Southern intelligence by adding that 11 of those states were Confederate, and Delaware and Kentucky had never left the Union or abolished slavery.

The commissioners had boarded the River Queen thinking slavery would end with the war. Now Lincoln and Seward had given them cause to think it might not, if the Confederate states rejoined the Union immediately. It was a clever piece of positioning. Southern lawyers and politicians might win what Confederate generals must lose. Peace with honor might be had. Peace with slavery might not be too much to hope for, at least for a decent interval, with the specifics worked out under Southern influence.

And then there was the obvious question. If the Confederacy agreed to reunion, Stephens asked, would the Confederate states retake their seats in Congress, with their Constitutional rights restored? Lincoln thought they would, and he also thought they should, he said, but only congress had that power. He might influence the outcome favorably to the South when the time came, but he would never negotiate with rebels having arms in their hands.[16]

Hunter insisted that the Confederate leaders had a right to negotiate for their people that Lincoln must recognize. History was full of such precedents. Charles the First had treated with rebels in the English Civil War. Lincoln saw his opening and took it, with his face lit up by “that indescribable expression that often preceded his hardest hits,” as Stephens recalled from their old friendship. “And Charles the First lost his head,” the president said. That was all he knew about that. It was Seward who knew history.[17] To his credit, Hunter counterpunched cleanly. Charles lost his head because he refused to settle with rebels, not because he treated with them. But Lincoln’s agile sarcasm was the jibe of the day, and it angered and humiliated the Virginian.[18]

Knowing the hostile tenor of the U. S. congress and the slim to nonexistent prospect that its erstwhile Southern members would soon be welcomed back, Stephens took another legal tack. Having issued the Emancipation Proclamation under his Constitutional war powers, the president could also use them to end the war, guaranteeing the South’s political rights whether congress liked it or not. But instead of defending his transformational legacy unabashedly, Lincoln was somehow moved to repeat what he had said before, in venues public and private. He had never favored immediate emancipation, which would lead to “many evils.” He had resorted to it only to shorten the war. A gradual emancipation, to take full effect, say in five years, would better serve both races.[19]

As if to endorse Lincoln’s thought, Hunter, the virtual embodiment of the Southern slaveholding aristocracy, said it would be cruel to free the slaves abruptly. They were used to working only by compulsion. If the compulsion stopped suddenly, slave and master would starve alike. But something about the Virginian, or more likely what he stood for, seemed to annoy Lincoln. In reply, the president dipped into what Stephens recalled as his vast supply of pointed stories. He was reminded, he said, of an Illinois farmer who planted a field of potatoes and let his hogs dig them out and feed on them. When a neighbor came along and asked him what would happen when the ground froze, the farmer scratched his head. “It may come pretty hard on their snouts,” he said, “but in the end it will be root hog, or die.”[20]

Hunter was insulted again. Lincoln had pierced the veil of noblesse oblige behind which the slave owners hid, and the Virginian confronted the Northerners hotly. They were offering the Confederate states and their people nothing but unconditional submission, he said. Seward tried to sooth him. No words like unconditional submission had been used, he said, or anything implying humiliation. The federal authorities were not conquerors further than they required obedience to the laws.[21] Lincoln made it plain that in the wake of a voluntary reunion he would exercise his pardoning power liberally. No one would hang if the Confederate states came home voluntarily.[22]

Lincoln went on to the more agreeable subject of compensation for his guests’ human property, knowing it was not just a matter of cash but a salve for Southern pride. With the war over slavery still raging, the commander in chief told his enemies that the North was as responsible for slavery as the South. Northern shippers had brought the slaves from Africa, and Northern merchants and politicians had been complicit in slavery from the beginning. Should the war stop now, and the Southern people end it themselves, they ought to be subsidized for it. Though only congress could do that, and he could make no promises on the subject, he himself would “rejoice” to be taxed on his own little property to help the South bear the cost. He made it clear that he would endorse an appropriation of $400 million and claimed that some of the men who would support it would astonish them.[23]

What the president had said was so startling that his Secretary of State got up and paced the elegant carpet as he disavowed it (though a cynic might think he was playing the bad cop’s part). “The United States has already paid on that account,” Seward said, having spent so much on the war and lost so many lives. “Ah, Mr. Seward,” Lincoln replied, “You may talk so about slavery if you will, but if it was wrong in the South to hold slaves, it was wrong in the North to carry on the slave trade,” and it would be wrong to hold on to the wealth the North had procured by selling slaves to the South if the North took the slaves back again without compensation.[24]

Rather than reanimating the discussion, Stephens later said, Lincoln’s overture provoked a pause, “as if all felt that the interview should close.”[25] In the end, the whole thing had broken down over Lincoln’s demand for reunion and Davis’s refusal to consider it. The conference’s only immediate result was Lincoln’s kind agreement, at Stephens’s request, to release the Georgian’s nephew from a prisoner of war camp in a frigid corner of Ohio.[26]

In a brotherly parting of their own, Hunter turned to Seward, a former Governor of New York. The Capitol’s new dome had been under construction when Hunter had left it four years earlier. “Governor,” he asked wistfully, “how is the Capitol? Is it finished?” Seward said it was and described it in all its glory.[27] And then the reluctant enemies took their “formal and friendly leave of each other,” as Stephens later said. Lincoln and Seward withdrew first, but not before Seward took his friend by the hand. “God bless you Hunter.”[28]

Lincoln and Seward returned to Washington by way of Annapolis on an overnight steamboat run. On Saturday morning, Seward returned to his office and told the Associated Press that the peace talks had failed. The markets dropped in New York and Lincoln’s stock rose in Washington. The Republican Congress and press were relieved that their softhearted President had not traded victory for peace.

Returning to Grant on the Mary Martin, the commissioners spent Friday night at City Point commiserating with him. Then they passed through his siege line on their way back to Richmond on Saturday, skirting a cannonade.

Holding on like a drowning man to a last thin hope for peace, Lincoln worked through Sunday on a formal peace offer and called his cabinet to the White House that night to hear it. He proposed to declare a general amnesty and ask congress to pay a $400 million indemnity to all the slave states, whether loyal or in rebellion, half to be paid if the rebel states put down their arms by April 1, the other half if the Thirteenth Amendment were ratified by July 1. All confiscated property except slaves would be returned, and the president would recommend “liberality” on all points beyond executive control. It would cost no more than a military victory, he said, not to mention the cost in blood.

But as Lincoln and every cabinet minister knew, the political poison of generosity on the brink of victory could wreck his second term before it began. His Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher, an old friend from their lawyering days, was convinced that the president would have taken his proposal to Congress nevertheless if only one of his cabinet members supported it. Not one of them did. For reasons lost to history, Seward was not there, and the others rebuffed him unanimously. He gave it up with a characteristic sigh. “You are all against me,” he said, and preserved for posterity on the back of his written proposal a note that recorded their rejection. [29]

The commissioners had returned to Richmond, despondent and empty handed, to the gloating Confederate president. The failure that dispirited Lincoln energized Davis, as a tool to rally his people: The Yankees had humiliated the Confederate defeatists, exposing them as naive. There was nothing to do but fight to the last man and boy.

Judge Campbell composed a report to the Confederate congress. Bereft of the invective that Davis had wanted him to add, its cold recitation of the North’s proffered terms was provocative enough: No treaty could be made with the Confederate States, whose legitimacy would be recognized “under no circumstances.” The authority of the United States must be restored, and the Confederate states must accept “whatever consequences may follow,” though individuals could rely on Lincoln’s clemency. It was “brought to our notice” that the U. S. Congress had adopted a Constitutional Amendment banning slavery.[30] None of the conciliation they had heard from their hosts made it into the commissioners’ report, nothing about Lincoln’s confession of a shared responsibility for slavery, or the prospect of compensation for the slaves, or a potential restoration of the Confederate states’ rights, or the notion of blocking the 13th Amendment.

On Monday, as Edward Alfred Pollard, The Richmond Examiner’s editor and a fierce Davis critic later said, a multitude gathered for a war rally at the African Church, Richmond’s most commodious interior space, “as if there was no invasion of sanctity of so lowly a house of God as that where Negroes worshiped.” Even Pollard later recalled that the eloquent Confederate President, all but broken by illness, stress, and fatigue, never gave a more stirring address. The African Church was “rent with shouts and huzzahs, and its crazed floor shaken under applause” as Davis scorned the edicts of “his Majesty, Abraham the First.” By the summer solstice, Davis said, the North would sue for peace and its leaders would know that when they spoke at Hampton Roads that “they were speaking with their masters.”[31]

Hunter had left the River Queen angry, but after a friend chided him sadly for a speech in which he echoed Davis’s bellicosity when he knew there was nothing to be gained by more killing, Hunter came to Davis’s home with two like-minded Senators. Davis owed it to “his own reputation and character as well as to a gallant people,” Hunter said, “to leave some evidence” of having tried to ease their suffering when their cause had become hopeless.[32] Acquainted with Davis’s ego, Hunter offered to introduce a resolution in the Senate asking the president to seek peace, lifting the onus from his shoulders. Instead of thanking Hunter, Davis cast him into the void.

Send me a resolution, Davis said, and I will send you a prompt reply. Then he walked down the street to the home of the highly respected South Carolina Senator Robert Woodward Barnwell and asked him to see to it that any such resolution would be drafted to let the people distinguish Davis’s resolve from Hunter’s cowardice. Within hours, it was all over Richmond that Hunter had been conquered by fear. There was no more talk of peace from him.

For weeks after the peace conference ended, with the Confederacy’s sure defeat coming closer day by day, Judge Campbell cajoled Confederate leaders to resume negotiations and, if need be, accept the terms offered on the River Queen. No one would take the responsibility. Lee pointed to Davis, Davis pointed to congress, congress pointed back to Davis, and no one dared move toward reunion, though nearly everyone but Davis understood its inevitability. As Campbell later recalled, “Mr. Davis, with the air of a sage, declared that the Constitution did not allow him to treat for his own suicide.”[33]

Lee retreated and Richmond fell two months after the peace conference, and Davis and his government fled. Of all the senior Confederates, only Judge Campbell remained to face the Northern conquerors and do what he could for his people. He surely must have known that he was draping a noose around his neck.

When Lincoln went down to conquered Richmond, he met with Campbell on the Union warship Malvern. Even then, with the rebel capital at his feet, Lee on the run, and the Confederacy all but dead, Lincoln offered to consider any terms, so long as the Confederates stopped fighting, recognized the federal authority, and understood that he would take no backward steps on slavery. Indeed, he offered to let Virginia’s legislature reassemble and vote her back into the Union as a step toward restoring Southern self-government, which could have set a wider precedent. But there was no elected authority left in Richmond to consider the offer on the spot, and when Lincoln returned to Washington, Stanton talked him into withdrawing it.

Years after the war, Davis would insist that Hunter and his ilk did “injustice to the heroic mothers of the land in representing them as flinching from the prospect of having their boys of sixteen ‘or under’ exposed to the horrors and hardships of military service.” Hunter would reply that Davis knew little about mothers.[34]

Within a dozen weeks after the Hampton Roads conference, the Carolinas were looted, the better parts of Columbia and Richmond were burned, the Confederacy’s leaders were jailed, Davis was captured in Georgia with a thinly escorted band of frightened women and children, and Lincoln was dead. So were some 10,000 men and boys who had been alive and well when their leaders lit cigars on the River Queen. In lieu of a peaceful reconciliation, the rebellion would end in the only existential defeat that Americans have ever endured. Years would pass before the occupied Confederate states were admitted back into the Union. A chain of ugly consequences has unfolded ever since.

On the summer solstice, Alec Stephens made an entry in his diary in a Boston prison cell, recalling Davis’s prediction at the African Church that the Confederacy would prevail by then. “Brilliant though it was,” Stephens wrote, the speech had been all but demented. Stephens had thought at the time that if Davis did not negotiate reunion, “by the summer solstice there would barely be a vestige of the Confederacy left. I am, with him and thousands of others, a victim of the wreck.”[35]

- [1] James B. Conroy, Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865 (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014), the only book ever devoted to the subject, assembles and assesses comprehensively the primary and secondary sources on the peace conference’s origins, conduct, aftermath, and impact.

- [2] Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Sectary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, 3 vols., Howard K. Beale and Alan W. Brownsword, eds., (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 2:179.

- [3] Elizabeth Blair Lee, Wartime Washington: The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth Blair Lee, Virginia J. Lass, ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 463.

- [4] See Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012),270-2.

- [5] Both letters are in Abraham Lincoln, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Roy B. Basler, ed., 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-1955), 8:275-6.

- [6] Ibid., 8:248.

- [7] Ibid., 8:282.

- [8] Ibid.

- [9] New York Herald, February 5, 1865.

- [10] Alexander A. Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, 2 vols. (Philadelphia, PA: National Publishing Co., 1870), 2: 599-600; John A. Campbell, Reminiscences and Documents Relating to the Civil War During the Year 1865 (Baltimore, MD: John Murphy & Co., 1877), 11.

- [11] Ibid., 6, 10, and 12-13; Robert M. T. Hunter, “The Peace Commission of 1865,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 3 (January-June 1877): 173.

- [12] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:609; Campbell, Reminiscences, 11-13.

- [13] Allen Thorndike Rice, ed., Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln (New York: American Publishing Co., 1886), 97; Robert Garlick Hill Kean, Inside the Confederate Government: The Diary of Robert Garlick Hill Kean (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), 196.

- [14] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:610-12.

- [15] Ibid., 2:611-12; Rice, Reminiscences,7-8, and 14.

- [16] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:612-13; Rice, Reminiscences,51; Robert M. T. Hunter, “The Peace Commission—Hon. R. M. T. Hunter’s Reply to President Davis’ letter,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 4 (December 1877): 306; New York Times, July 22, 1895, 5.

- [17] Augusta Chronicle and Sentinel, in the New York Times, June 26, 1865; Hunter, “Peace Commission”, 176; Kean, Inside the Confederate Government, 196.

- [18] See, Hunter, “Reply to President Davis”,396.

- [19] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:613-14.

- [20] F. B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1894), 211; see also Myrta Lockett Avary, Recollections of Alexander Stephens (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1910), 137; Rice, Reminiscences, 14.

- [21] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:616-17.

- [22] Rice, Reminiscences, 15.

- [23] Ibid., 17; Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:617; Bradley T. Johnson, “The Peace Conference in Hampton Roads,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 27 (January-December 1899): 376; Hunter, “Peace Commission”, 174.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:618.

- [26] Avary, Recollections, 141.

- [27] Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner, 4 vols. (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1893), 4:205.

- [28] E. A. Pollard, Life of Jefferson Davis (Philadelphia, National Publishing Company, 1869), 480-1.

- [29] Abraham Lincoln, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 450; Abraham Lincoln, Collected Works, 8:261.

- [30] Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 2 vols. (D. Appleton and Co., 1881), 2:619-20.

- [31] Davis’s speech is in Stephens, Constitutional View, 2:624-5. Pollard’s description of the rally and the speech is in Pollard, Life of Jefferson Davis, 471-2.

- [32] Hunter, The Peace Commission Reply, 307.

- [33] John A. Campbell, “Open Letters: A View of the Confederacy from the Inside,” in The Century Magazine, 38, no. 6 (October 1889): 952.

- [34] Jefferson Davis, “The Peace Commission,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 4, (November 1877): 208-14; Hunter, The Peace Commission Reply, 312.

- [35] Avary, Recollections, 241.

If you can read only one book:

Conroy, James B. Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014.

Books:

Avary, Myrta Lockett. Recollections of Alexander Stephens. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1910.

Campbell, John A. “Reply of Judge Campbell,” in Transactions of the Southern Historical Society, 1, (January-December 1874):22-28, (Letter from Judge Campbell dated December 20, 1873).

———. “The Hampton Roads Conference, Letter of Judge Campbell,” in Transactions of the Southern Historical Society, 1, (January-December 1874):187-90, (Letter from Judge Campbell dated August 6, 1874).

———. Reminiscences and Documents Relating to the Civil War during the Year 1865. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1877.

———. Recollections of the Evacuation of Richmond. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1880.

———. “Evacuation Echoes,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 24 (1896): 351-3.

———. “Open Letters: A View of the Confederacy from the Inside,” The Century Magazine 38, no. 6 (October 1889): 950-4.

———. “Papers of John A. Campbell,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 42 (October 1917): 45-75.

Cleveland, Henry. Alexander Stephens, in Public and Private, with Letters and Speeches, Before, During, and Since the War. Philadelphia: National Publishing Co., 1866.

Davis, Jefferson. “Jefferson Davis, The Peace Commission – Letter from Ex-President Davis” in Southern Historical Society Papers 4 (November 1877): 208-14.

———. “Jefferson Davis, Letter – Reply to Mr. Hunter,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 5 (May 1878): 222-7.

———. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 2 vols. D. Appleton and Co., 1881.

———. “The Peace Conference of 1865,” in The Century Magazine 77, no. 55 (November 1908): 67-69.

Goode, John. “The Hampton Roads Conference,” in The Forum 29 (March 1900): 92-103.

Gorgas, Josiah. The Journals of Josiah Gorgas, 1857-1878. Sarah Willfolk Wiggins, ed. Tuskaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

Hunter, Robert M. T. “R. M. T. Hunter, The Peace Commission of 1865,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 3 (April 1877): 168-76.

———. “R. M. T. Hunter, The Peace Commission – A Reply,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 4 (December 1877): 3-18.

Johnson, Bradley T. “The Peace Conference,” in Southern Historical Society Papers 27 (January-December 1899): 374-7.

Jones, John B. A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary of the Confederate States Capital, 2 vols. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1866.

Kean, Robert Garlick Hill. Inside the Confederate Government, the Diary of Robert Garlick Hill. Kean Edward Younger, ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Lee, Elizabeth Blair. Wartime Washington: The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth Blair Lee. Virginia J. Lass, ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Lee, Fitzhugh. “Failure of the Hampton Roads Conference,” in The Century Magazine 52 (July, 1896): 476-8.

Pollard, E. A. Life of Jefferson Davis. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1869.

Stephens, Alexander. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. 2 vols. Philadelphia: National Publishing Co., 1870.

Stephens, Robert. “An Incident of Friendship,” 45 Lincoln Herald (June 1943): 18-21.

Weitzel, Godfrey. Richmond Occupied. Richmond: Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee, 1965.

Burlingame, Michael. Abraham Lincoln, A Life. 2 vols., Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Brumgardt, John R. “The Confederate Career of Alexander H. Stephens: The Case Reopened,” in Civil War History 27, no. 1 (March 1981): 64-81.

Carr, Julian S. The Hampton Roads Conference. Durham, N.C.: 1917.

Cleveland, Henry. Alexander H. Stephens in Public and Private. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1866.

Connor, Henry G. John Archibald Campbell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920.

Harris, William C. “The Hampton Roads Peace Conference: A Final Test of Lincoln’s Presidential Leadership,” in Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 21, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 31-61.

Holzer, Harold and Mark E. Neeley. Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory. New York: Orion, 1993.

Johnson, Ludwell H. “Lincoln’s Solution to the Problem of Peace Terms, 1864-1865,” in The Journal of Southern History 34, no. 4 (November 1968): 576-86.

Johnston, Richard M. and William H. Browne. Life of Alexander Stephens. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1878.

Kirkland, Edward C. The Peacemakers of 1864. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

McPherson, James M. “Lincoln and the Strategy of Unconditional Surrender,” in Gabor S. Boritt, ed., Lincoln the War President: The Gettysburg Lectures. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

———. “No Peace Without Victory” in This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, 167-83.

Parrish, William E. Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative. Columbia.: University of Missouri Press, 1998.

Sanders, Charles W., Jr. “Jefferson Davis and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference: ‘To secure Peace to the two countries’,” in The Journal of Southern History 63, no. 4 (November 1997): 803-26.

Saunders, Robert, Jr. John Archibald Campbell, Southern Moderate, 1811-1889. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Schott, Thomas E. Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia, A Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Simms, Henry H. Life of Robert M. T. Hunter. Richmond, VA: The William Byrd Press, 1935.

Smith, Elbert B. Francis Preston Blair. New York: Free Press/Macmillan, 1980.

Smith, William Ernst. The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, 2 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1933.

Temple, Wayne C. Lincoln’s Travels on the River Queen During the last Days of His Life. Mahomet, IL: Mayhaven Publishing, 2007.

Toews, Rockford. Lincoln in Annapolis, February 1865. Annapolis: Maryland State Archives, 2009.

Turner, Justin T. “Two Words,” Autograph Collectors’ Journal 2, no. 3 (April, 1950): 3-7.

Von Abele, Rudolph. Alexander H. Stephens. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946.

Westwood, Howard C. “Lincoln at the Hampton Roads Peace Conference,” Lincoln Herald 81 (Winter 1979): 243-56.

———. “The Singing Wire Conspiracy,” Civil War Times Illustrated 19, no. 8 (December 1980): 30-35.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.