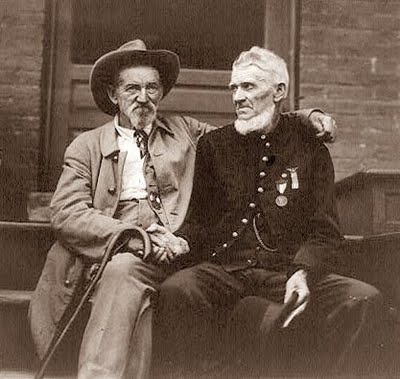

Union and Confederate Veterans

by James Marten

Veterans' experience of the aftermath of the Civil War.

Union and Confederate veterans shared many of the experiences of American veterans of more recent conflicts. Like the World War II veterans who are often referred to as “the Greatest Generation,” former Yankees and Rebels became examples of perseverance and loyalty. Like stereotypical veterans of the war in Vietnam, they were often troubled by post-traumatic stress issues and physical disabilities. Like the reservists and National Guardsman who have carried much of the burden of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, they were citizen-soldiers who returned to homes and families when their fighting was over. And, like virtually all veterans of American wars, the time they spent as soldiers was dwarfed by the time they spent as veterans.

The 1.5 million Union and perhaps 600,000 Confederate veterans were very visible members of post-war society. For one thing, they dominated political offices in both the North and the South. Most U. S. presidents during this period had fought for the Union, and scores of veterans from both sides served as governors, senators, and congressmen, while countless thousands served in state and local offices. But veterans’ importance to American society and to the legacies of the Civil War transcended their political influence.

By the 1880s, many Americans would have walked past monuments to Civil War soldiers in town squares, cemeteries, or other public places in the North and South. But the “old soldiers,” as they were already being called, were still only in their forties or fifties and still very much a part of the communities in which they lived. They were most prominent as members of veterans’ organizations and as participants in Memorial Day commemorations and July Fourth celebrations.

Civil War veterans formed many different veterans’ associations. Some consisted of all the men living in a single town or county, while others were formed by survivors of specific armies, corps, regiments, or even companies, and still others were formed by unique groups like prisoners of war or members of the signal corps. But two organizations dominated. By the 1880s, as many as 400,000 former Yankees belonged to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which was founded in 1866 and reached its membership peak twenty years later. The United Confederate Veterans (UCV) grew out of a number of smaller associations in 1889 and boasted 160,000 members by 1900. The GAR and UCV organized at the national, state, and local levels, with the local “posts” named after famous generals or local heroes. A number of “soldiers’ newspapers” were published to support the activities of the GAR and UCV. Papers like the American Tribune, National Tribune, and Ohio Soldier published war memoirs, reports from soldiers’ reunions, and information about pensions for GAR members, while the Confederate Veteran was the official publication of the UCV for forty years.

The GAR’s motto, "Fraternity, Charity and Loyalty," reflected the major priorities of the organization (priorities that were shared, in fact, by the UCV). Their monthly meetings and annual “encampments”—the latter also welcomed family members and friends—were meant to fulfill the “Fraternity” aspect of the motto, as they revolved around telling war stories, eating “soldiers’ meals” of beans, hardtack, and coffee, and recreating military style camps and even re-enacting battles. Social events, including group tours of southern battlefields by GAR members, picnics, plays, and other performances were important ways of maintaining friendships and camaraderie. Many of these events were also fund-raisers designed to help fulfill their vow of “Charity,” which was directed toward helping fellow veterans who had fallen on hard times by providing groceries, a month’s rent, or some other short-term aid. “Loyalty” was fulfilled partly by supporting the Republican Party; although the GAR was officially non-partisan, it was a close ally of the party of Lincoln and lobbied hard for the soldiers’ interests, especially pensions. Veterans also displayed their loyalty and inspired it in others by participating in Memorial Day festivities. Beginning in the late 1860s, on May 30 towns and cities throughout the North commemorated with parades and speeches the sacrifices of the men who died to save the Union and the contributions of the men who had survived. Veterans donned their GAR uniforms and marched in formation; veterans and townspeople alike decorated the graves of dead soldiers; former officers and a few enlisted men, along with noted clergymen and civic leaders, spoke about the lessons of the war, the noble deeds that should inspire all Americans, and the beneficent results of the war on the United States.

Confederate veterans and their fellow southerners also commemorated the sacrifices and bravery of former Rebels. Confederate Memorial Day was usually held on April 26, but in some states was celebrated later in the summer. It featured the same somber and celebratory aspects as its northern counterpart.

Memorial Day parades and speeches made it easy for Americans to think of Civil War veterans as distinguished old men with gray beards, elegant bearings, and bittersweet memories of lost comrades. In fact, the lives of Union and Confederate veterans were much more complicated. They were often able to blend back into families and communities fairly easily, but, like veterans of any war, some found it more difficult to readjust to civilian life.

Although many Civil War veterans were very successful after the war in business, politics, and life, many believed that the war had prevented them from meeting their expectations for economic success. They had spent the best years of their young manhood in the army. Union soldiers had been away while the men who remained at home profited from the booming economy, while Confederate soldiers saw family fortunes and farms crumble under the pressure of invasion and the collapse of the slave economy. Historians have only begun to measure this common belief among veterans that the war had held them back. A book on veterans from the small Iowa city of Dubuque, for instance, argues that their service had relatively little influence on their successes or failures, while a recent book on returning Virginians found that they often had to rely to unprecedented extent on private and public sources of relief, including churches and wealthy neighbors. Economists have suggested that men who experienced sustained combat tended to suffer problems at higher levels than other men, which also affected their economic well-being.

Although the term “post-traumatic stress” is a modern way of describing the effects of war on some individuals, the condition was certainly known during and after the Civil War. The failure of a man’s courage in the face of combat or when confronted with having to support a hard-pressed family after the war, was usually attributed to a failure of will or masculinity rather than to a medical condition. But “soldier’s heart,” as some people called it, clearly affected countless soldiers on both sides, who ended up in state asylums for the insane suffering from delusions, insomnia, paranoia, and other symptoms that were just beginning to be understood in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

The unprecedented number of men—perhaps hundreds of thousands—with psychological or physical disabilities inspired the federal government and most state governments in both sections to establish soldiers’ homes and pension systems for disabled veterans.

Federal pensions were awarded to Union veterans incapacitated for manual labor—the amount of the pension varied from a few dollars a month to as much as $25 or $30 depending on the extent of one’s disability—who suffered their injury or illness while in the army. The disabilities claimed by soldiers ranged from the loss of arms and legs to chronic dysentery and fevers. However, by the end of the century, eligibility had expanded to include conditions that developed after leaving the service. In fact, simple old age was often enough for a veteran to be “rated” as disabled. The steady expansion of pensions led to their comprising up to 30 percent of federal expenses, the single largest item in the budget at the turn of the century. This led to a great deal of criticism by the Democratic Party, who accused veterans of “raiding the treasury” and suggested that many pensioners had actually been short-term conscripts or men who had served in the rear, safely away from the fighting. The pensions granted by former Confederate states, on the other hand, were smaller and far less controversial than federal. pensions. Despite the criticism of the federal pension system, as the first major federal social welfare program in the United States, it became one of the models for the social security system designed during the mid-1930s. In the twentieth century Congress authorized payment of pensions to Confederate veterans.

For those men for whom a pension was not enough, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) was created in 1869 with branches in Dayton, Ohio, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Togus, Maine. It eventually had nearly a dozen branches in places ranging from Virginia to California and Tennessee to South Dakota. In addition, beginning in the 1880s, most northern states and many former Confederate states established homes for disabled or elderly soldiers. At a time when the care of adult dependents was left largely to families or to local poor houses, the federal and state homes were the first government institutions to provide relatively comfortable and safe places for men who could not support themselves and whose families could not afford to care for them. The soldiers’ homes became symbols of the nation’s gratitude to its veterans. In addition, because most were built outside of towns in picturesque natural settings, they also became tourist attractions and gathering places for residents of nearby cities. For instance, Milwaukeeans celebrated the Fourth of July at the Northwestern Branch of the NHDVS in the 1870s and 1880s. In the South, state soldiers’ homes became physical reminders of the Lost Cause and the men they housed became, as one historian called them, “living monuments” to the Confederacy’s noble defeat. The semi-military discipline and procedures followed at the federal and state homes conflicted with the inevitable desire of the residents to remain more or less independent. Taverns and brothels often appeared nearby, and the men frequently got into trouble with local authorities as well as administrators of the homes. Inevitably, the worst threat to the discipline and health of residents was the excessive drinking that plagued many of the men. Nevertheless, as the first government-supported institutions dedicated to caring for adults, the soldiers’ homes paved the way for future government programs. Indeed, the NHDVS was converted into the modern Veterans Administration in 1930.

The post-war experiences of the 150,000 or so African American veterans of the Union army were both similar and different from white veterans. Like their white comrades, they often joined GAR posts. Recent research suggests that many posts in northern cities were integrated, with both black and white members, and that African Americans often held positions of honor in those posts. The GAR was officially color-blind, so there was no formal segregation of black and white veterans in the organization. However, many black Union veterans actually lived in the South where, by necessity, their GAR posts were racially divided. The GAR also provided one of the few settings in which black and white veterans could recognize their shared experiences and commemorate their shared sacrifices. Recognizing the contributions of black soldiers did not, however, lead white veterans to campaign on their behalf for greater civil rights.

Although they faced the same challenges as other freed slaves during the decades after the war—the gradual loss of their political rights, economic disadvantages, and violence at the hands of groups like the Ku Klux Klan—their war service did provide black veterans with some advantages. They tended to receive more respect from other African Americans and whites and to take leadership positions in their communities. In addition, they had access to federal benefit programs, namely the pensions and soldiers’ homes established by the federal government. Although they had a harder time than whites in providing supporting evidence for their pension applications, perhaps 80,000 black veterans received pensions from the federal government, which eased the economic distress facing many black southerners.

Historians have been able to study Civil War veterans despite the fact that neither they nor their families tended to write about their lives after the shooting stopped. As a result, it is often difficult to know how they and their wives and children experienced war’s aftermath. The short-story writer Hamlin Garland, whose father volunteered to fight and marched with Sherman to the sea before returning home in late summer 1865, offered a hint of what it was like for a soldier to return home and to face the long years of veteran-hood in a short story called "The Return of a Private” and in the first chapter of his autobiography, Main Travelled Roads.[1] The story begins when his father, Richard Garland, and several other dusty, tired, hungry veterans get off a train in a small Wisconsin city. There is no parade, no welcoming committee—their families do not even know they have arrived. Richard wearily walks the few miles to his little farm, where he pauses before a rickety fence. His family rushes up to him; he tightly embraces his wife and teenaged daughter, but the homecoming is nearly ruined when his young sons fail to recognize him. The crisis passes when he offers an apple to the youngest boy—Garland’s little brother, born about the time Richard left for the army—and the day ends happily enough. But Hamlin recorded the long term results of the senior Garland’s service, which surfaced in his sharp temper and soldierly habits, his quick use of the whip to discipline his boys—as well as his penchant for telling long war stories. The family uneasily adapted to a sterner, more dominating father and husband than they remembered from before the war. More importantly, like many veterans, even those with no obvious physical disabilities, Richard faced a very long road to recovering from the war. "His farm was weedy and encumbered. . . . His children needed clothing, the years were coming upon him, he was sick and emaciated.” The drama and excitement and sense of duty that the war had brought to him were long gone, and he now faced the anticlimactic hardships of his mundane civilian life: "The common soldier of the American volunteer army had returned. His war with the South was over, and his fight, his daily running fight with nature and against the injustice of his fellow-men, was begun again.” As it does for all men who fight and survive a war, life went on for Civil War veterans—but it would never quite be the same.

-

[1] Hamlin Garland, Main-Travelled Roads: Six Mississippi Valley Stories (Boston: Arena Publishing Company, 1891).

If you can read only one book:

Logue, Larry M. and Barton, Michael, eds. The Civil War Veteran: A Historical Reader (New York: New York University Press, 2007)

Books:

Carmichael, Peter S. The Last Generation: Young Virginians in Peace, War, and Reunion (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), Chapter 8.

Clarke, Frances M. War Stories: Suffering and Sacrifice in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), Chapters 5 and 6.

Cloyd, Benjamin G. Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010)

Dean, Eric T. Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999)

Gannon, Barbara A. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

Hunt, Robert The Good Men Who Won the War: Army of the Cumberland Veterans and Emancipation (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010)

Johnson, Russell L. Warriors into Workers: The Civil War and the Formation of Urban-Industrial Society in a Northern City (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003)

Kelly, Patrick J. Creating a National Home: Building the Veterans’ Welfare State, 1860-1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997)

Logue, Larry M. To Appomattox and Beyond: The Civil War Soldier in War and Peace (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996), Chapters 5-8

Marten. James Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

McClurken, Jeffrey W. Take Care of the Living: Reconstructing Confederate Veteran Families in Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009)

McConnell, Stuart Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992)

Rosenburg, R. B. Living Monuments: Confederate Soldiers' Homes in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993)

Shaffer, Donald R. After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004)

Simpson, John A. S.A. Cunningham and the Confederate Heritage (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994)

Skocpol, Theda Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992)

Williams, Rusty My Old Confederate Home: A Respectable Place for Civil War Veterans (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010)

Organizations:

Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War

A heritage group devoted to commemorating the contributions and memory of Union veterans.

Sons of Confederate Veterans

A heritage and advocacy group devoted to commemorating the sacrifices of Confederate soldiers and the southern past

National Women’s Relief Corps

A self-titled patriotic association dedicated to commemorating the Grand Army of the Republic.

Web Resources:

National Park Service website with histories and other information of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

Library of Virginia’s on-line name index from the Confederate Veteran magazine.

Electronic issues of the National Tribune, a Union veterans’ newspaper, at the Library of Congress.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.