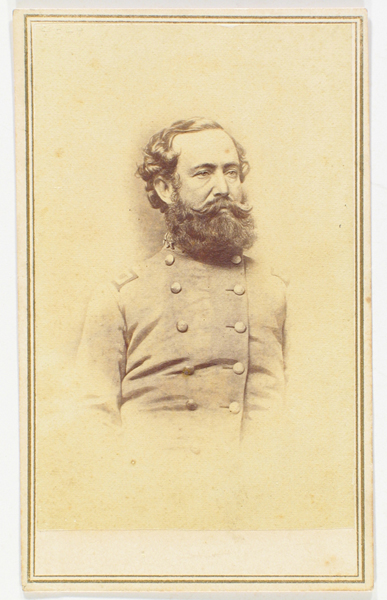

Wade Hampton III: The Successor to J.E.B. Stuart in Command of Lee's Cavalry

by Robert K. Ackerman

Biography of Confederate Lieutenant General Wade Hampton III

No one in the Civil War era better represents the tragic history of South Carolina, the state which led the South into secession, than Wade Hampton III, and few more accurately represent the tragedy of the American South. He and John Caldwell Calhoun are the two South Carolinians represented in the Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol, indicating these two as the state’s most famous citizens. The emphasis here should be on tragedy; Hampton was indeed a tragic figure. His early life was spent as a major cotton planter, dependent on slave labor. Obviously, that era ended with the Civil War. He then became an effective military leader in the Confederate war effort, and, also obviously, that ended in defeat. After the war he became the most famous of the Southern politicians who led their states out of radical Reconstruction, and he did so advocating a limited measure of justice for the freed people. His effort to involve the freed blacks in a limited role in political life failed before the racist determination to proscribe any political involvement by African Americans. South Carolina took another sixty years to reach a position near to that advocated by Hampton.

Wade Hampton III was as close to being an aristocrat as the American experience permitted. He was of the third generation of landed wealth. His grandfather, Wade Hampton I, was a frontiersman who by sheer determination, free from the inhibition of troublesome scruples, acquired vast estates in South Carolina, Mississippi and Louisiana, and ownership of hundreds of slaves. In 1823 the Niles Weekly Register indicated that Wade Hampton was “probably the wealthiest planter in the South.” With all of this be became a general, serving with genuine distinction in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. He also served in the state legislature and in Congress. Wade Hampton II inherited his father’s wealth, and by distinguished service in the War of 1812 continued the military tradition. Wade Hampton II reached the peak of the much cherished Southern ideal of a wealthy slave-holding planter, complete with the proper sense of noblesse oblige. The Hampton home Millwood was the center of South Carolina society and influence. If Hampton II represented the flood tide of the planter ethos, his son, Wade Hampton III, represented the ebb tide.[1]

Wade Hampton III was born in 1818 and grew to maturity at Millwood, inheriting the wealth and prestige of a great planter family. After graduating from the South Carolina College he married into a distinguished Virginia family and began a career of operating slave-worked plantations in South Carolina and Mississippi. Unfortunately, Hampton assumed great debts to enlarge his holdings in Mississippi, assuming that the prosperity of cotton producing plantations would continue on into the future. The coming of the Civil War ruined any possibility of Hampton making good on these additional investments.

In 1852 Hampton began his political career by serving in the state legislature. With one very impressive exception, there was little to distinguish his political service in the 1850’s. There was a move by the most radical of Southern politicians to reopen the slave trade, closed since 1808. Hampton successfully and eloquently opposed the measure, characterizing the slave trade as “cruel and inhuman,” that from a slave-holding planter, to the manor born. Remarkably, there is evidence that Hampton was influenced in this by Francis Lieber, once Hampton’s teacher at the South Carolina College and later an intellectual influence in the Lincoln administration.[2]

Lincoln’s election in 1860 impelled South Carolina into a state of frenzied excitement, caused by distrust of Lincoln with regard to the institution of slavery. This state in December 1860 led the South into secession. Although he did not doubt the state’s right to secede, Hampton thought it an unwise move. Still, once secession was accomplished, he threw himself into the effort wholeheartedly.

Hampton went directly to the newly elected Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Montgomery and offered his services. With Davis’ approval he organized and equipped at his own expense the Hampton Legion, complete with infantry, cavalry and artillery elements. Indicative of the fast flow of events, the Legion trained at Camp Hampton, journeyed to Virginia, and participated in the Battle of Manassas in July of 1861. From the start Hampton proved to be a courageous and effective military commander. He was without formal military training; yet, he proved to be among the best of the Confederate leaders. He became one of the three Confederate lieutenant generals without West Point training (the others being Nathan Bedford Forrest and Richard Taylor, son of Zachary Taylor). Hampton was encouraged by the military tradition of his father and grandfather, even inheriting their swords, and he proved to be an able student of tactics. He also inherited a love of the great outdoors, having become a storied hunter and fisherman, often leading large hunting expeditions on his Mississippi lands. That experience aided him in his remarkable ability to understand the importance of terrain in battle tactics.

At Manassas Hampton and his Legion were instrumental in turning back the Union attempt to turn the Confederate left and then took part in the countercharge which led to the Union rout. Hampton received his first wound in that first great battle. Afterwards, he assumed command of an infantry brigade in the army commanded by General Joseph Eggleston Johnston. Hampton’s brigade guarded part of the defensive line in northern Virginia.

When the Union Major General George Brinton McClellan in the spring of 1862 attempted a flank attack on Richmond, approaching from the east on the peninsula between the James and York Rivers, Johnston moved to cover that front. Hampton’s brigade was a part of that campaign, playing an essential role in joining with a brigade commanded by Major General John Bell Hood in repelling a Union attempt to turn the Confederate left. Hampton’s brigade was a part of the Confederate offensive in the Battle of Seven Pines. Hampton received another wound, this time to his foot. He remained on horseback while a surgeon removed the minié’ ball. Joseph E. Johnston was also wounded, and he was replaced by General Robert E. Lee. Hampton served in the command of Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson in the Seven Days Campaign, which resulted in McClellan’s withdrawal down the peninsula.

After the peninsula campaign Hampton received orders to assume command of a cavalry brigade in the units commanded by Major General J.E.B. Stuart. While Hampton was quite different from his commander, and the two at times disagreed, Hampton’s greatest service was in the cavalry. And it was a natural development because Hampton was a superb horseman with a natural understanding of topography and endowed with the ability to make quick and reasoned decisions under fire. His first real test was in guarding the Confederate flank in the move into Maryland, and Hampton did well in retarding the Union advance. There was little for the cavalry to do in the actual Battle of Antietam, but they again were important in the retreat back into Virginia. In October after Antietam Hampton participated in a daring raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, serving briefly as the military governor of that Pennsylvania town.

The next significant battle was at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862. Hampton led a number of successful raids behind the Union lines prior to and after the battle. This brings to mind that Hampton was a part of a general re-defining of the role of cavalry. The development of rifled weapons and the resulting increased accuracy of fire made frontal assaults by mounted cavalry suicidal. In the Civil War cavalry was of use primarily in scouting, raiding, reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance, and serving as dismounted infantry with the ability to move rapidly from one position to another. Hampton became especially adept in having his men dismount and fight as infantry and then move quickly to another position and do the same.

In the spring of 1863 Hampton led his brigade to the south of Virginia to remount and refresh his unit. He, therefore, played no role in the Battle of Chancellorsville. On returning to the cavalry command, Hampton was of vital importance in repelling the surprise Union attack at Brandy Station, at one time fighting the enemy from two sides, the battle in which Frank Hampton, a younger brother, was killed.

The Rebel cavalry’s next assignment was to protect the flanks of Lee’s army in its move north into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Stuart’s units in their daring aggressiveness strayed too far to provide the main army the needed reconnaissance, rejoining the Army of Northern Virginia only on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Probing the Union right, Hampton’s unit engaged in head-on fights with the enemy cavalry, including a unit commanded by George Armstrong Custer. Hampton received several serious wounds, disabling him for months.

Hampton returned to duty in November of 1863. In February 1864 he led an attack on Union cavalry under the command of Major General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, just north of Richmond, foiling an attempt to free the Union prisoners in the Libby Prison and perhaps kill President Davis. The Union troopers retreated to safety down the Virginia peninsula. Hampton and Kilpatrick would meet again.

In May the Union army under the direct command of Major General George Gordon Meade, acting at the directions of General Grant, then in overall federal command, launched the overland campaign, beginning with the Battle of the Wilderness, followed closely by Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. In the midst of these major battles federal cavalry led by Major General Philip Henry Sheridan struck toward Richmond and killed J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern. Although Hampton was now the senior officer of Lee’s cavalry, the commanding general waited until August to appoint him officially in charge of the cavalry for the Army of Northern Virginia. In his role as senior officer Hampton led units in a major Battle at Trevilian Station, preventing an attempt by Sheridan to join with units from the west in isolating Lee’s army and Richmond.

In the following months Hampton and his men protected the southern end of the Confederate lines around Petersburg, thereby keeping open the vital supply route from the south. Hampton performed superbly in this task. In September he led several units behind the Union lines and returned with 2,486 cattle, the famous “beefsteak raid. “ In October while fending off a major Union attack at Burgess Mill Hampton witnessed his two sons being wounded. Upon rushing to the two young men he realized that Preston was dying and Wade IV seriously, but not mortally, hurt. The grief-stricken father returned to his duty in directing artillery fire.

The following months proved to be similarly pathos-laden. Lee ordered Hampton to return to Columbia in February of 1865 in the hope that this South Carolinian could somehow pull together forces sufficient to ward off Sherman’s approach from Savannah. Newly promoted to lieutenant general, Hampton found the Confederate forces so scattered as to make an effective resistance impossible. Faced with impossible odds, Hampton abandoned his home town and from a distance witnessed the red glow as much of the city and his two homes burned.

On February 22, 1865, General Lee as commander of all Confederate forces ordered General Joseph E. Johnston to assume command of the Army of Tennessee. Remarkably, these scattered and disheartened units came together to make an army effective enough to fight a respectable battle and negotiate a respectable peace. Hampton commanded Johnston’s cavalry and did so with genuine ability. He led a surprise raid on Kilpatrick’s cavalry, and he essentially planned the Confederate tactics in the last major battle at Bentonville, North Carolina.

In the chaos of the surrender of Johnston to Sherman and the death throes of the old South, Hampton made desperate attempts to escort the escaping Jefferson Davis to Texas and continue the struggle from the west. Fortunately for Hampton, these efforts came to naught, and the exhausted general accepted the inevitable peace.

The next years involved Hampton’s efforts to put the pieces back together. He employed freed slaves in attempts to regain some of his wealth by producing cotton on his Mississippi lands. His debts proved to be overwhelming, and in 1868 he went into bankruptcy, retaining some lands on which he and his sons made continuing efforts.

In South Carolina Hampton was clearly the most popular leader of the white population. Despite his efforts to discourage appeals that he allows himself to be a candidate for the office of governor, the voters almost elected him, losing to James L. Orr by only a few votes. Hampton opposed the radical government established by the directions of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. Still, in the midst of this social revolution Hampton became an advocate for suffrage for the freedmen, albeit limited by requirements of literacy or ownership of property. He remained active in the Democratic Party, often participating in state and national party politics.

For much of the time of radical Reconstruction, i.e., rule by freedmen and Republicans, Hampton was out of the state. He spent time in Mississippi, trying to gain livelihood from his remaining lands; in Maryland working with Jefferson Davis in an insurance business; and in Charlottesville, Virginia, caring for his sick wife. Despite these distractions, he kept informed of South Carolina politics.

In 1876 the Democratic Party nominated Hampton for the office of governor. In one of the most violent and corrupt campaigns Hampton, who disapproved of the shady side and actually appealed for the votes of the black citizenry, became governor, ending radical Reconstruction. His administration was significantly honest and characterized by real attempts for at least limited justice for blacks. He actually appointed more blacks to office than the preceding Republican governors had.

In 1868 the state legislature elected Hampton to the U.S. Senate, where he served two terms. Away in Washington, Hampton’s influence in his home state waned, as the dominant white’s gradually limited black access to political activities. Senator Hampton became a leading advocate for reconciliation of the North and South. In 1890 the most bitterly racist elements defeated Hampton and assumed control of the state.

In Hampton’s final years he served one term as Commissioner of Pacific Railroads, a sinecure in The Cleveland administration. He died in 1902, virtually penniless, having lived in a home in Columbia given by grateful citizens. The failure of his efforts to include the black population in at least a limited role in the state’s political affairs was the final tragedy of this storied aristocrat and Confederate general. He has remained an iconic figure in the South Carolina culture.

Wade Hampton III

- [1] Ronald Edward Bridwell, “The South’s Wealthiest Planter: Wade Hampton I of South Carolina, 1854-1835” (PhD diss., South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, 1980), 1.

- [2] Senator Wade Hampton III, speech delivered in the Senate, December 10, 1859, Hampton Family Papers, South Carolinian Library, University of South Carolina.

If you can read only one book:

Ackerman, Robert K. Wade Hampton III. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

Books:

Andrews, Jr., Rod. Wade Hampton: Confederate Warrior to Southern Redeemer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Cisco, Walter Brian. Wade Hampton: Confederate Warrior, Conservative Statesman. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2004.

Cooper., William J. The Conservative Regime, South Carolina, 1877-1890. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968.

Drago, Edmond L. Hurrah for Hampton!: Black Red Shirts in South Carolina During Reconstruction. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Jarrell, Hampton M. Wade Hampton and The Negro, The Road not Taken. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1949.

Longacre, Edward G. Gentleman and Soldier: A Biography of Wade Hampton III. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Wellman, Manly Wade. Giant in Gray: A Biography of Wade Hampton of South Carolina. Dayton, OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1988.

Wells, Edward L. Hampton and His Cavalry in ’64. Richmond, VA: B.F. Johnson Publishing, 1899.

———. Hampton and Reconstruction. Columbia, SC: The State Company, 1907.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Wade Hampton Papers 1791-1907

The Southern Historical Collection in the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections, University of North Carolina. This collection includes documents relating to Wade Hampton III as well as his father and grandfather. 200 South Rd., Chapel Hill, NC 27514. 919 962-3765. wilsonlibrary@unc.edu . Open M-G 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.Hampton Family Papers

University of South Carolina South Caroliniana Library. This collection also includes documents relating to Wade Hampton III as well as his father and grandfather. 910 Sumter St., University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C. 29208. 803 777-3131. Open M-F 8:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. and S 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m.