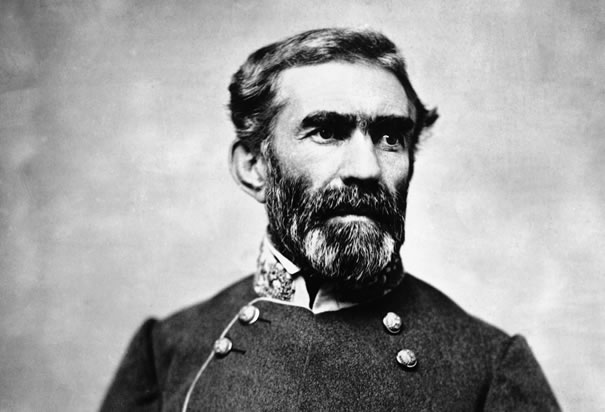

Braxton Bragg

by Judith Lee Hallock

Biography of Confederate General Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg. The mere mention of his name today elicits giggles and guffaws, as though his entire military career were a joke. While it is true that his battlefield command proved non-stellar, his reputation has suffered more than that of others who performed even more poorly. One reason for this may be attributed to his unfortunate personality - contentious, irascible, quarrelsome, vengeful, and quick to blame others for his mistakes. These traits, along with suffering frequent illnesses, do not make an effective leader of men. As the Civil War began, despite his cantankerousness, Bragg was held in high regard; great deeds were expected of him. Unfortunately, in the crucible of war, he did not live up to those expectations.

Bragg grew up in Warrenton, North Carolina, located in an affluent tobacco-growing area, where slaves made up more than half the population. Braxton’s father, Thomas Bragg, settled in Warrenton around 1800. He worked as a carpenter, and eventually became a successful contractor. In 1803, Thomas married Margaret Crosland, with whom he had twelve children. Braxton, the eighth child, was born on March 21, 1817.

Braxton attended the Warrenton Male Academy for nine years, where his teachers regarded him as an excellent student. By the time he was ten, his father had decided that Braxton would attend the Military Academy at West Point, and he worked assiduously at winning an appointment for his son. After years of lobbying, Thomas succeeded, and at the age of sixteen Braxton entered the academy with the class of 1837. He did well, improving his standing each year and graduating fifth in his class of fifty.

Shortly after graduation, Bragg received appointment to the Third Artillery and orders to report to Florida. For two years the army had been fighting the Seminole Indians, who refused to leave their traditional home and move west. Here began Bragg’s episodes of a “weak constitution,” perhaps brought on by his unhappiness with his assignment.

June of 1845 brought a welcome change to Bragg’s assignment when he received orders to join General Zachary Taylor’s army in the defense of Texas against Mexico. The Mexican War brought Bragg many accolades. A story went around that during the final Mexican attack at the Battle of Buena Vista, Taylor rode up to Bragg’s artillery battery and ordered, “A little more grape, Captain Bragg!”[1] Inspired by the general, the battery fired more vigorously and drove the enemy back. On the strength of this apocryphal anecdote and his success in the battle, Bragg emerged as a popular hero, celebrated and feted from New Orleans to Mobile to Warrenton to New York City, among other places. It even brought him a wife: At an event in his honor at Thibodaux, Louisiana, he met Eliza (Elise) Brooks Ellis, the daughter of a wealthy sugar planter. They married on June 7, 1849.

Bragg spent the next few years on the frontier, while constantly seeking reassignment to a more congenial position. Finally, at the end of 1855, disgusted with the army, he resigned, purchased a sugar plantation and more than 100 slaves, and became a successful planter.

When the secession movement heated up, Bragg once again became involved with military affairs. When Louisiana seceded in January of 1861, the governor appointed Bragg commander of the state army. On March 7, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, appointed him brigadier general in the Confederate army. Davis ordered Bragg to Pensacola, Florida, to oversee the activities around Fort Pickens, still in Union hands. Bragg set about changing his volunteer troops into drilled, disciplined soldiers. By September, Davis was so pleased with Bragg’s performance that he promoted him to major general.

Bragg’s reputation soared in those early days. One newspaper declared that Bragg was one of the elite of the old United States army, ranking high in “skill, courage, and noble conduct.”[2] A West Point professor believed Bragg to be the best of all the Confederate generals. Theophilus Holmes, another Confederate general, asserted that Bragg “possessed military capacities of a very high order.” Respect for Bragg’s military abilities made him a popular figure in the early days of the Confederacy.

In February of 1862, Davis ordered Bragg to move with his finely trained soldiers to reinforce General Albert Sidney Johnston’s army in northern Mississippi. Bragg took command of the Second Corps, and he acted as chief of staff for Johnston. On April 6, the Confederates attacked the Union forces at Pittsburg Landing, or Shiloh, as the Northerners called it. The Southern army slowly advanced throughout the day, driving the Federals back toward the river. Despite the tangling of the various units on the field, Bragg led the forces near the center of the battlefield for several hours before moving to the Confederate right. Here, at the Hornet’s Nest, Bragg spent five hours directing piecemeal assaults before the Federals caved about 5:00 P.M. As he began to drive forward, Bragg received orders to fall back from General P.G.T Beauregard, who had taken command of the army upon the death of Johnston earlier in the day. Bragg believed that this withdrawal cost them the victory. Federal reinforcements arriving on the field during the night turned the tide the next day. By 2:00 P.M. on the seventh the Confederate line had collapsed.

On April 12, 1862, Bragg became a full general, the fifth ranking officer in the Confederacy, and Davis assigned him to permanent command of the Western Department. In July, Bragg determined that an invasion into Kentucky could reap many benefits for the South. To get his troops into position, he ordered an unprecedented transfer of an army by rail on the twenty-third. The 776-mile trip, via six railroads, went smoothly and proved to be the most successful part of the entire operation.

On August 28, Bragg began his advance from Chattanooga into Kentucky with his army of 27,000. The first encounter with the enemy came at a Federal garrison at Munfordville. Heavily outnumbered, the 4,000 Federals quickly surrendered. That proved to be the only real success of the campaign. Planning to unite forces with Major General E. Kirby Smith, Bragg left the army under the command of Major General Leonidas Polk while Bragg traveled to Lexington to confer with Smith, a useless endeavor, as Smith never did unite his forces with Bragg’s. Polk moved the army to Perryville, disobeying Bragg’s orders to concentrate the forces to deter the advance of Federal Major General Don Carlos Buell. Polk’s deployment of the army for battle at Perryville proved faulty. Bragg rejoined the army on October 8, just as the battle was about to be joined. Despite Polk’s mistakes, Bragg managed to drive Buell’s army back nearly two miles before stalling. Polk deserved his commander’s censure, and Bragg made certain to include that in his report on the battle. Rethinking his plans for Kentucky, during the night Bragg began retreating to Tennessee. So ended Confederate hopes for Kentucky.

Bragg settled his reinforced army a few miles northwest of Murfreesboro. As the Federals under the command of Major General William S. Rosecrans advanced on December 31, 1862, Bragg ordered his Army of Tennessee to pivot on its right, swinging northeast to try to force Rosecrans across the Nashville Pike, thus cutting the Federal line of retreat. The rough, broken terrain of the battlefield interfered with this grand movement, and although the Federals were caught off guard, they soon rallied and established strong positions. For ten hours the battle raged with neither side achieving a victory. The first day of the new year saw desultory firing, but on January 2, Bragg ordered an assault on a Union division in front of Polk’s position. After a bloody eighty minutes of fighting, Bragg realized the Federals could not be dislodged. At 11:00 P.M. he ordered his army to retreat from Murfreesboro.

The Army of Tennessee next set up camp in the Tullahoma area. Bragg occupied himself for the next six months in his favorite activities, reorganizing the army and quarreling with his subordinates, many of whom expressed their dissatisfaction with Bragg’s leadership.

In late June, Rosecrans came after him again, forcing Bragg to retreat to Chattanooga with barely a shot fired. Remarkably, in his report Bragg insinuated that the loss of this important territory came about when his opponent fought unfairly by taking advantage of the Confederates’ weakness.

Bragg remained in Chattanooga for several weeks, until in late August Rosecrans began a flanking movement around the city. Bragg quickly moved southward in order to protect his line of communication. As the Federals moved through the mountainous country, their three corps became widely separated, making them vulnerable to attack. On two occasions Bragg had excellent opportunities to strike the Federal forces in detail; each time the disobedience and cowardice of Bragg’s subordinate commanders allowed the Federals time to recognize their danger.

Rosecrans hurriedly concentrated his scattered forces at Chickamauga Creek. On September 19 and 20, 1863, a huge battle raged as Bragg attempted another grand pivot with the aim of forcing the Federals into McLemore’s Cove where he had a good chance to destroy them. The Confederates held their own throughout the nineteenth, advancing at some points. During the night, reinforcements, under the command of Lieutenant General James Longstreet arrived from Virginia. Bragg immediately set about reorganizing the army into two wings with Longstreet commanding the left wing, and Polk the right. Again, he hoped to achieve success with his grand pivot, which would begin on the right, followed by Longstreet joining battle as Polk’s advance pushed the Federals out of their positions. Once again, however, Polk disobeyed orders. As Bragg fumed, Polk relaxed at his headquarters. Finally, after much prodding, and four hours later than Bragg had directed, Polk began his advance, but then allowed piecemeal assaults to exhaust his troops.

Meanwhile, on the left of the Confederate army, Longstreet formed his soldiers and waited for Polk’s attack to produce results. Bragg, active on the field all day, finally lost patience and ordered Longstreet’s troops forward. By sheer chance, at that precise moment, a gap inadvertently opened in the Union line, allowing Longstreet’s men to pour through. The Federals broke and fled, all but Federal Major General George Thomas who held fast on Snodgrass Hill, covering the Northerners’ wild retreat until nightfall.

Rosecrans concentrated his army at Chattanooga. Bragg moved his Army of Tennessee to the heights overlooking the city. Again, he spent the next several weeks reorganizing the army and quarreling with his subordinates, frittering away the advantages he had gained at the Battle of Chickamauga. At one point his subordinates petitioned Davis to replace Bragg, an extraordinary action on their part. Davis visited the army, met with the discontented officers, discussed the situation with Bragg, and ultimately decided to leave Bragg in command.

Meanwhile, Rosecrans had been replaced with Major General Ulysses S. Grant. On November 24 Grant’s forces unexpectedly, and easily, swept away the few Confederates under Longstreet’s command deployed on Lookout Mountain on Bragg’s left. The following day, just as unexpectedly and easily, the Federals chased Bragg’s entire army down the far side of the seemingly impregnable Missionary Ridge. Again, Bragg blamed others for the debacle. He accused Major General John C. Breckinridge of being drunk throughout the three-day crisis. If so, Bragg showed poor judgment in relying upon his subordinate’s assessment of his troops’ ability to hold their position. He even accused Lieutenant General D.H. Hill, who no longer served with the Army of Tennessee, of having demoralized the troops he had formerly commanded.

On November 29, Bragg asked to be relieved from command. To his chagrin, Davis accepted the resignation with unseemly haste.

Davis did not allow Bragg a long rest from military affairs. In February 1864, he appointed the general to serve as his military adviser, an office that allowed Bragg to wield considerable power over his army cohorts. During his eight-month tenure Bragg’s considerable managerial skills served the Confederacy well. The efficiency of several military institutions improved under his supervision. Davis relied heavily upon Bragg’s understanding of military affairs, seeking his expertise or opinion of a variety of matters. Although he served the Confederacy well as military adviser, Bragg came to the office too late in the war to have a great impact on its outcome.

Bragg’s tenure in Richmond came to an end in October 1864. While he continued to carry out the duties of military adviser for the president, Davis ordered Bragg to Wilmington, North Carolina, the last Confederate port open to blockade runners. His performance here proved to be the most shameful of his career. He failed to properly prepare for the inevitable Federal assaults on Fort Fisher, and when the much-anticipated attack occurred in January 1865, the commanding general remained in Wilmington, several miles distant from the fort, wringing his hands. Despite desperate pleas for aid from inside the fort, Bragg did nothing, and later came up with illogical and pusillanimous explanations for his inaction. From his prison cell in the North, Major General W. H. C. Whiting, the fort’s wounded commander, wrote a scathing critique of Bragg’s actions that day. Whiting died shortly thereafter.

Not long after the fall of Fort Fisher, Wilmington, too, fell into enemy hands while Bragg was in Richmond tending to business. In his report, Bragg made it clear that he was not there at the start of the battle, once again shifting the blame to others.

Following this debacle, Bragg spent the last weeks of the Confederacy’s existence as a subordinate to General Joseph E. Johnston. With the remnants of the Army of Tennessee, Bragg’s old command, Johnston attempted to block Major General William T. Sherman as he advanced toward the eastern seaboard.

As the Confederate government fled Richmond in April 1865, Bragg joined the fugitive Davis and used his influence to convince the president that they had, indeed, been defeated. On May 10, 1865, as Bragg and his wife made their way home, Union cavalry captured them. He immediately received a parole and had no further trouble with the Federals.

Bragg died in Galveston, Texas, on September 27, 1876; he is buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Mobile, Alabama.

During the war, Bragg held a greater range of responsibilities than any other Confederate general. He commanded the Gulf coast fortifications at the start of the war; he served as corps commander and chief of staff at Pittsburg Landing (Shiloh); he commanded the Army of Tennessee, a position he held longer than anyone else, and during which he led it to its northernmost point and won its one great victory; he served as one of Davis’ two military advisers; and he ended the Civil War as a subordinate field commander once again.

Bragg left much to be desired as a field commander. He suffered many illnesses, migraine headaches, boils, dyspepsia, and rheumatism, to name a few, especially during stressful times, and the remedies available to him may have been as damaging as the illnesses themselves. Perhaps his greatest shortcoming was his failure to inspire loyalty, confidence, or obedience in his subordinates. Those under his command frequently ignored his orders, refusing to carry out their assigned responsibilities. He also lacked the resolution and the good luck, other than the breakthrough at Chickamauga, of a successful field commander. Bragg failed to learn from his mistakes, and he seemed to remain ignorant of the changes in tactics required to meet the technological changes that made the battlefield a different experience from that for which his West Point training had prepared him.

Bragg’s many frailties have shaped much of the literature on him to the extent that his real accomplishments have been ignored or distorted. But Bragg had supporters, too. One in particular, General Joseph E. Johnston, perhaps said it best. After succeeding Bragg in command of the Army of Tennessee in late 1863, Johnston realized the difficulties of working with many in that army’s officer corps. In a letter to Senator Louis T. Wigfall, he advised the senator, “When you see me overrun by the simultaneous efforts of the enemy’s numbers & faction here [within the army], have a little charity for Bragg.”[3]

Bragg had a difficult personality; those he considered friends had his unwavering support and praise; all others he went out of his way to criticize and badger. This led to frequent embarrassing quarrels with his subordinates, and on two extraordinary occasions they conspired in petitioning Davis to remove him from command of the Army of Tennessee. While serving as President Davis’ military adviser, he took every opportunity to denigrate and thwart those he disliked. He carried much of the responsibility for the removal of General Joseph E. Johnston, a friend and supporter, from command of the Army of Tennessee for a brief period in 1864. This gave Johnston’s successor, Lieutenant General John Bell Hood, the opportunity to essentially destroy that army at Franklin and Nashville, Tennessee, before the command was returned to Johnston.

Bragg is an example of the Confederacy’s failure to utilize its human resources in the best possible way. An able administrator, Bragg spent most of the Civil War as a mediocre field commander. Although he maintained many loyal friendships, he went out of his way to create lasting enmities. Sincerely devoted to the Confederate cause, he unfortunately contributed to its demise.

Braxton Bragg

- [1] Grady McWhiney, Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969, p.90.

- [2] Ibid., pp.155-156

- [3] Judith Lee Hallock, Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Vol.2. Tuscaloosa Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1991, p.159.

If you can read only one book:

Grady McWhiney, Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969. & Judith Lee Hallock, Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Vol. 2. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1991.

Books:

Thomas Lawrence Connelly, Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

Thomas Lawrence Connelly, Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.