Causes of the Civil War

by Michael E. Woods

Without the presence of slavery, disunion and war would not have taken place. But did slavery's presence make that outcome inevitable?

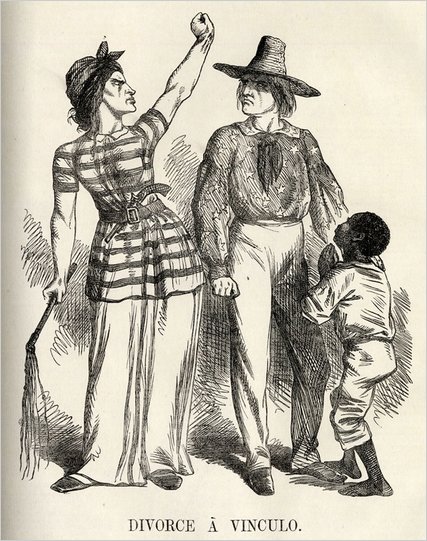

What caused the Civil War? To ask the question is to invite intense debate. History’s present-day relevance is on full display in the countless discussions—online and offline—that this topic continues to generate. Americans remain deeply and personally invested in the Civil War, making it an exciting but challenging field for anyone committed to rigorous scholarship. When South Carolina diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut explained secession in 1861, she focused on visceral rage: "We are divorced, North from South, because we hated each other so."[1] Today, traces of these feelings linger, making careful study essential to a thorough understanding of the war that Chesnut’s contemporaries fought.

Students of Civil War causation should clearly state the historical problem they wish to solve and carefully decide where in time to begin and end their narratives. Good history begins with precise questions. Asking what caused the war is not the same, for example, as asking why soldiers enlisted, or whether the North and South were more alike or different by 1861. Our questions must also inspire nuanced answers. “What caused the war?” invites us simply to list sectional differences or major events. We might quarrel over how to rank the enumerated items. We might (more profitably) explore the connections between them. But the “what” question risks implying that history is a series of isolated episodes rather than an intricate process of change over time. Historians do their best work when they ask “why” or “how” questions. These questions reflect and respect the complexity of the past and invite more satisfying answers. We might ask: “Why did the Civil War happen?” Or: “How did disunion and war become possible?”

The narratives we write in response must start and stop at specific points in time. Most studies of Civil War causation conclude in April 1861 with the outbreak of war in Charleston, South Carolina. But when should the narrative start? This decision dramatically influences accounts of the war's origins. If we start with the Constitutional Convention, sectional conflict might appear as an unavoidable result of compromises made, and decisions postponed, by the Founding Fathers, with the war serving as a bloody climax to philosophical debates commenced at Independence Hall. But if we begin in 1819 with the clash over slavery in Missouri, or in 1845, with the annexation of the slaveholding Texas Republic, our narrative might spotlight a series of crises over westward expansion. The war would grow from sectional wrangling over the spoils of continental empire. To choose a third starting point, if we commence in 1860 with the election of Abraham Lincoln, the war will be a battle over the legitimacy of secession.

Each of these narratives offers considerable insight. But each one inevitably obscures important points as well. The first account, for example, situates the war within a longer struggle between southern defenders of states’ rights against primarily northern champions of federal power. But what about the ways in which southern statesmen used the federal government to defend their interests, particularly in the recovery of runaway slaves? This narrative would make little sense to northerners like Gideon Welles (later Secretary of the Navy under Abraham Lincoln), who denounced the Fugitive Slave Act as a "consolidating measure," an “abandonment” of the “doctrines and teachings of Jefferson,” and an "invasion of the states."[2] Similarly, despite the significance of the territorial issue, the final secession crisis commenced with a presidential election, not the conquest of fresh acreage. And while the war’s immediate trigger was secession, thorough accounts of its origins must explain why an election that followed the letter of constitutional law provoked disunion.

This essay offers a basic framework for thinking about Civil War causation. It proceeds from two foundational questions and adopts a unique approach to the chronology. The questions open up layers of puzzles to solve: Why did eleven states secede after the 1860 presidential election? Why did secession trigger war? I will address them in reverse order, working backward from 1861. Each episode on the road to war grew out of earlier conditions and events, and this essay reverses the timeline to explore what made each one possible. This does not mean that the outcome was inevitable. But it shows that every historical explanation leads to more questions, which can only be answered by moving further back in time. Each layer of historical excavation uncovers a few answers and many more challenges.

Why did secession lead to war? Many accounts focus on President Abraham Lincoln's handling of the secession crisis. But the Confederates fired first; President Jefferson Davis's perspective is, therefore, equally important. Obviously, the U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter, an island installation in Charleston, South Carolina’s expansive harbor, defied the Confederacy's claim to independence. Most other federal property in the seceded states had been seized peacefully, but Fort Sumter capitulated only after enduring the opening salvos of the war. There were, however, deeper motivations for the bombardment. By April 1861, Davis faced two challenges: one was to vindicate the independence of the seven Deep South states (Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina) which then comprised the Confederacy. The second was to convince the other eight slave states, home to most of the South's industry and white manpower, to join them. Many upper south states, including Virginia and Arkansas, had rejected secession so far, and even in the Deep South it had been controversial. War offered a solution to both problems. In the seceded states, armed conflict would transform dissent and apathy into martial zeal. "[U]nless you sprinkle a little blood in the face of the people of Alabama," warned one correspondent, "they will be back in the old Union in less than ten days!"[3] War would also force upper south whites to choose sides, and Davis expected they would fall in with the Deep South once the shooting started. Davis chose war, and at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, southern artillery commenced a bombardment of Fort Sumter that lasted more than thirty hours. Ironically, the cannonade killed no one. But it inspired citizens on both sides to rally to the colors. Northerners responded to Lincoln's April 15 call for 75,000 volunteers with patriotic fervor. Four slave states—Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—responded by seceding. Davis did not win over the border region, but the Confederacy swelled to eleven states and nine million inhabitants. The war had begun.

But why did Lincoln cling so tenaciously to Fort Sumter? The unfinished and undermanned citadel was ill-prepared to withstand a determined barrage. Some of Lincoln's closest advisors, including Secretary of State William Seward, urged him to abandon it in order to preserve an uneasy peace and prevent strategic upper south states like Virginia from seceding. But Lincoln's resolve grew from his understanding of the Union and his duties as president. He believed that the Constitution’s “more perfect Union” was perpetual and that Confederates had rebelled against lawful authority. Like Andrew Jackson in the Nullification Crisis (1832-33), he would execute the laws peacefully if possible, forcibly if necessary.

Lincoln outlined his intentions in his Inaugural Address of March 4, 1861. No other American president inherited such a volatile situation: seven states had seceded, eight more seemed poised to follow, and most federal property in the Deep South, including forts, arsenals, and dockyards, had fallen to Confederates. Lincoln pledged neither to seek war, nor to buy peace at any price. He repudiated secession and deemed the Union "unbroken." He promised that the laws would be "faithfully executed in all the States" and that the government would "defend and maintain itself." This need not cause bloodshed, but if force was required to maintain normal government operations, he would use it. Lincoln concluded that his opponents would decide the outcome. "In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war....You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to 'preserve, protect, and defend it.'"[4] This meant holding federal property, including Charleston’s Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida. Lincoln resolved to replenish both garrisons' dwindling provisions and keep the Stars and Stripes flying. Fort Pickens never surrendered, but Confederates blasted Fort Sumter into submission before supplies arrived.

War exploded at the Charleston flashpoint because neither side could back down without sacrificing principle or losing face. But the confrontation resulted from secession. Confederates necessarily defended its validity; to Unionists, secession amounted to anarchy and treason. But why had the first wave of secession, in which seven states departed the Union between December 1860 and February 1861, not been halted? Threats of disunion had permeated American political rhetoric and a secession scare had been averted in 1850. Why was there no Compromise of 1861?

It was not for a lack of effort. Throughout the winter of 1860-61, members of the 36th Congress scrambled to enact compromise legislation. Moderates nationwide begged them to preserve the Union and keep the peace. "For God's sake," urged a Kentuckian, "and for the sake of humanity, persevere in the noble efforts at conciliation."[5] Both houses of Congress formed special committees to tailor a compromise. The content of their proposals reflected slavery’s central importance. No one doubted that a viable compromise must address slavery’s expansion and the return of fugitive slaves to their masters; these were the rocks on which the Union was foundering. Dozens of ideas circulated in Washington, but the leading plan came from Senator John Jordan Crittenden of Kentucky. The "Crittenden Compromise" consisted of six proposed constitutional amendments. Crittenden sought to avert secession by redefining the relationship between the federal government and slavery. His amendments would do the following:

Together, Crittenden's amendments would have weakened the federal government's ability to restrict slavery and required it to protect the institution. They were controversial not because they limited or expanded federal power generally, but because pro- and antislavery politicians disagreed about how that power should be used.

Despite provoking intense discussion, neither Crittenden’s proposal, nor anyone else’s, forestalled secession. To state the challenge Crittenden faced is to indicate why he failed: he and other would-be compromisers had to satisfy the most ardent proslavery extremists and the most unwavering antislavery zealots. To secessionist fire-eaters, the amendments offered only paper guarantees, not the ironclad security that they associated with southern independence. To antislavery Republicans, Crittenden's plan seemed destined to make the federal government an openly proslavery agency. Lincoln threw his influence as president-elect against any compromise that would allow slavery to expand. He offered concessions on other points, including the recovery of fugitives and a constitutional amendment prohibiting Congress from abolishing slavery. But against slavery expansion he urged congressional Republicans to stand firm, lest they forsake a core tenet of their party's platform. Lincoln clarified the issue in a letter to his friend, future Confederate Vice President Alexander Hamilton Stephens: “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.”[6] But it was a world of difference. In this formulation, the conflict was both a matter of policy—should slavery be extended (by active federal protection) or restricted (by active federal prohibition)?—and of morality. Neither facet of the problem was easily compromised. The prospects for compromise faded away as Congress adjourned in early March.

But why was compromise necessary? Lincoln received only a plurality (just under 40%) of the popular vote, but his share of the electoral votes (180 out of 303, with 152 needed to win) far exceeded the constitutionally-required majority. He would likely face a hostile Congress, as well as the Supreme Court that had rendered the stridently proslavery Dred Scott decision. How much damage could Lincoln do? Why did his by-the-book election push seven Deep South states to secede?

Lincoln's letter to Stephens and his party's rejection of Crittenden’s amendments help explain why the Republican victory so deeply disturbed proslavery southerners. Historians have labored to show that most Republicans were not “radical abolitionists,” that they did not immediately threaten slavery in the fifteen states where it was legal. Lincoln wearily reiterated this point in his Inaugural, disavowing any intention to “interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.”[7] But Republicans did endorse an antislavery agenda calculated to contain slavery and facilitate its eventual collapse. The fact that this would be entirely constitutional was of little comfort to those with an economic, political, or social stake in slavery as a labor system and a means of racial domination, and in the billions of dollars invested in four million enslaved people.

Antebellum Republicans acknowledged that slavery was a state institution which Congress could not touch. Most abolitionists actually agreed, leading some of them to denounce the Constitution as a wickedly proslavery compact. But Republicans combined a variety of antislavery policy proposals to craft a strategy for bringing slavery to a gradual end. They advocated a two-pronged campaign: Congress would outlaw slavery in areas under its direct jurisdiction, including western territories and Washington, DC. This would hem in the slave states, surrounding them with free soil and depriving slaveholders of fresh land. Meanwhile, the federal government would stop supporting slavery, leaving it up to the states to return fugitive slaves and otherwise protect masters’ property claims. Thus, Republicans defied proslavery politicians by demanding that slavery truly be treated as a state institution – not one entitled to federal aid. Under these conditions, Republicans predicted that, like a scorpion encircled by fire, slavery would sting itself to death. Their pledge to respect slavery in the states, therefore was attached to predictions of slavery’s destruction. As New York Congressman Anson Burlingame put it, the “Republican party does not wish to interfere in the internal government or social institutions of the slave States, but merely to place around them a cordon of Free States. Then this horrible system will die of inanition; or, like the scorpion, seeing no means of escape, sting itself to death.”[8] Slavery would die by state-level abolition, as border and upper south states abandoned it, or by constitutional amendment, once the number of Free states reached three-quarters of the total. Republicans candidly discussed these goals. Their 1860 platform, for example, proclaimed that the “normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom” and condemned efforts to legislate for slavery’s expansion.[9]

The 1860 election was an unprecedented Republican triumph, and the prospect of a Lincoln administration alarmed many white southerners. Fresh memories of John Brown’s October 1859 raid made Lincoln’s victory seem even more dangerous. Lincoln’s predecessor had dispatched federal troops to crush the abolitionist conspirators—but could a Republican be trusted to do the same? Convinced that Republicans menaced slavery’s growth and stability, secessionists candidly justified their decisive response. South Carolina secessionists blamed antislavery “agitation” for the “election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” Upon Lincoln’s inauguration in March, they warned, the government would fall to a party that had “announced that the South shall be excluded from the common territory…and that a war must be waged against slavery until it shall cease throughout the United States.”[10] Republican gradualism did not make slavery’s death easier to swallow, especially for white South Carolinians, who lived among an enslaved black majority in a state where nearly half of white families owned slaves. They had every reason to secede first, which they did on December 20, 1860. Georgians agreed, recognizing that “anti-slavery” was the Republican Party’s “mission and purpose.” To avoid the “evils” of Republicans’ encirclement strategy, Georgia secession convention delegates led their state out of the Union.[11] Other secession documents followed similar logic; Mississippi’s was the most forthright. “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery,” proclaimed Magnolia State secessionists, and now they had to choose between “submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union.” Confronted by a party dedicated to “extinguish[ing]” slavery “by confining it within its present limits,” Mississippi secessionists chose disunion. “We must either submit to degradation, and to the loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede.”[12]

Given secessionists’ reading of Republican aims, their response to Lincoln’s election appears drastic but not necessarily irrational. But why did the Republicans win in 1860? Their party was six years old. It is not overly dramatic to call the party’s rise “one of the most striking success stories in political annals.”[13] How did Republicans convince a majority of free-state voters, few of whom favored abolitionism or any semblance of racial egalitarianism, to support them at the polls?

Lincoln did not face united opposition in 1860. Rather, the election developed into a four-way race. Democrats split into rival northern and southern wings, nominating Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas and the current vice president, Kentucky’s John Cabell Breckinridge, respectively. Led by upper and border south moderates, a new Constitutional Union Party rallied behind John Bell of Tennessee. But the proliferation of competitors did not by itself bring Republican success. Lincoln would have won even if all his rivals’ votes had gone to a single opponent.[14] Moreover, the four-sided contest largely became a pair of two-way races, pitting Bell against Breckinridge in the South, and Lincoln against Douglas in the North. It was Lincoln’s near sweep of the Free states (he divided New Jersey’s electoral votes with Douglas), coupled with northern demographic might, that secured his victory. Why did a commanding 54% of free-state voters support the rail splitter?

The Republican Party’s origins provide clues about its appeal. In 1854, the United States reached a fateful milestone on the road to civil war: the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It was in opposition to this law—condemned by Michigan Republicans as a “gigantic wrong”[15]—that the Republican Party coalesced. Ironically, the divisive law was not necessitated by the acquisition of new land. Rather, it was designed to organize governments for a region that, on paper, had belonged to the U.S. since 1803. Most of the Louisiana Purchase was already carved into states or territories, but a massive “Unorganized Territory”—covering part or all of modern-day North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Kansas, and Nebraska—remained in legal limbo.

White farmers who coveted these lands had an ally in Stephen A. Douglas. The pugnacious Democrat’s career was a product of westward migration; born in Vermont, Douglas thrived on the Illinois prairies and, as chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, he vigorously promoted western political and economic development. He yearned to establish governments in the Unorganized Territory, but earlier efforts had failed. Much of the opposition came from the South because the proposed territories lay north of the 36° 30’ line, which since 1820 had divided the Louisiana Purchase into slave and free zones. In 1854, Douglas offered a new plan: organize two territories, Kansas and Nebraska, not under the free soil restriction, but under the principle of popular sovereignty, which allowed territorial voters to decide for or against slavery. Southerners demanded that the bill explicitly repeal the Missouri Compromise. Douglas acquiesced, Congress approved, and in May President Franklin Pierce signed it into law.

Rather than stifle sectionalism, the Kansas-Nebraska Act unleashed a frightful debate that propelled the nation closer to war. To many northerners, the Act seemed like a conspiracy to transform land preserved for freedom into slave territory. Indeed, northern opposition began even before it became law. Shortly after Douglas introduced the bill, six northern legislators published an “Appeal of the Independent Democrats,” in which they castigated the proposal “as a gross violation of a sacred pledge; as a criminal betrayal of precious rights; as part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region, immigrants from the Old World and free laborers from our own States, and convert it into a dreary reign of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.”[16] Many critics of the bill began to build a new party opposed to slavery expansion. Some hoped that non-slaveholding white southerners might join, but many imagined it as a sectional organization; one editorialist concluded that “the People of the North and West” must “unite in a Party of Freedom, with a fixed purpose to regain possession of the Federal Government” from the Democratic Party, which had become an agent of slaveholders.[17] From this this wave of indignation the Republican Party was born.

Still, the party’s presidential triumph was not inevitable. Republican success required fusing disparate factions into a single organization. What could unite former Whigs, who wanted protective tariffs and federal support for railroads, with former Democrats, who demanded free land for western settlers and strict economy in public expenditures? How could seasoned antislavery activists cooperate with racists who objected to slavery expansion because they wanted the west reserved for whites? The Republicans were not a single-issue party and championed a variety of causes, including Democrats’ long-cherished homestead legislation and a Whiggish program of public support for internal improvements. But opposition to slavery’s expansion, and to the political power of slaveholders and their allies, glued the Republican coalition together.

Two features of antebellum politics made this possible—and boosted the Republicans’ popular appeal. First, the line between “slavery” and “other issues” was blurry. Northerners noticed, for example, that southern votes repeatedly blocked Senate approval of a homestead bill. They resented this stranglehold on this and other measures, especially when, as a Pennsylvanian wrote in 1850, “Northern interests as usual must succumb to Southern.”[18] It was a short step from this broad dissatisfaction to a much sharper critique of the so-called “slave power.” The notion that southern politicians exerted disproportionate power in the federal government was not far-fetched. The Constitution’s 3/5 Clause inflated slave-state influence in Congress and the Electoral College and it was no accident that a slaveholder was president for 50 of the 62 years before 1850. National policy—from the Fugitive Slave Act to the removal of Native Americans from rich cotton-planting lands in the Deep South—seemed to confirm that slaveholders wielded the levers of national power. Republicans capitalized on the issue, warning that the “national Government…is as fully under the control of these few extreme men of the South, as are the slaves on their plantations.”[19] Northerners opposed the slave power for diverse reasons, but their shared grievance swelled Republican vote tallies and embedded the slavery controversy into apparently unrelated issues.

Second, the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s results validated Republican opposition to popular sovereignty and to slavery’s champions. Popular sovereignty invited opponents and proponents of slavery to race to Kansas to determine its fate. The result was widespread fraud and violence. During a March 1855 election to choose a territorial legislature, thousands of Missourians, led by Senator David Rice Atchison, crossed the border to vote illegally for proslavery candidates. Antislavery settlers refused to acknowledge the proslavery legislature and established a rival government. Heavily armed northern migrants arrived to resist Missouri Border Ruffians and over the next four years, between fifty and two hundred people died in the clashes between them. Republicans pointed to Bleeding Kansas as proof of popular sovereignty’s failure and of the brutality of proslavery zealots.

The hostilities spread eastward from the Great Plains. In May 1856, Senator Charles Sumner, a Massachusetts Republican, condemned proslavery violence in Kansas, comparing slavery expansion to the “rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery” for the purpose of “adding to the power of slavery in the National Government.”[20] His deliberately provocative speech infuriated South Carolina Congressman Preston Smith Brooks, who beat Sumner into unconsciousness on the Senate floor two days later. For many northerners, Brooks personified the slave power, a menace to freedom in Kansas and free speech in Congress. The Bleeding Sumner incident increased support for the Republicans in the presidential election that November. Republican John C. Frémont finished second to Democrat James Buchanan, but came within two states of winning the contest and received a plurality of northern ballots.

Subsequent efforts to close the book on Kansas only reaffirmed, to Republicans at least, that slaveholders sought to use federal power to safeguard slavery’s expansion. In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its notorious decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Most famously, it held that Scott, a slave who had been taken from Missouri into free territory and sued for his liberty, could not sue because African Americans could not be U.S. citizens and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”[21] But the decision was also calculated to foster slavery expansion by ruling that neither Congress nor a territorial legislature could bar slavery from a territory. The fact that five of the nine justices hailed from slave states fueled conspiracy theories and supported claims that the slave power, as a New York editorialist wrote, had “converted” the Court “into a propagandist of human slavery.”[22] Similarly, President Buchanan’s subsequent efforts to push Congress to admit Kansas as a state under the proslavery Lecompton Constitution, which had not been fully submitted to Kansas voters for approval, provoked fierce resistance from Republicans and most northern Democrats, including Douglas, who believed that the “Lecompton swindle” violated popular sovereignty.[23] This political environment fertilized Republicans’ growth into the North’s leading party.

Of course, this account of the short- and medium-term roots of the Civil War leads to more questions. Why were many southerners so adamant about Kansas? The security of slavery’s northwestern flank had something to do with it, as did the desire to establish a precedent for territorial property rights that might be needed later in Mexico or Cuba. Why were many northerners primed to react so fiercely to the Kansas-Nebraska Act? Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) kept slavery in northerners’ minds and refreshed hostility toward the slave power that had flourished after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Why was westward expansion so divisive? One could trace the slavery expansion issue back in time, through the Compromise of 1850, the clash during and after the Mexican War (1846-48) over slavery’s status in the freshly-conquered southwest, Texas annexation, the admission of Missouri, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which barred slavery from the region between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River. Why did northerners fear southern domination? One could follow northern hostility to the slave power back through the Gag Rule debates (1836-44) over the reception of antislavery petitions in Congress, the lasting resentment of the 3/5 Compromise, to the Constitutional Convention – where, as James Madison put it, “the real difference of interests lay, not between the large and small but between the N. and Southn. States,” with the “institution of slavery and its consequences form[ing] the line of discrimination” between them.[24] To understand these sectional issues, we would then have to explore politics within regions and states. We could study how northern political candidates used the slave power theory to denounce local opponents who courted southern allies. We might examine how differences between the upper and lower south exacerbated sectional conflict by convincing cotton-state planters that their counterparts along the South’s vulnerable northern border might not defend slavery to the last ditch.

A thorough account of Civil War causation, therefore, could easily grow into a history of the United States to 1861. It would show that without the presence of slavery, disunion and war would not have taken place. But did slavery’s presence make that outcome inevitable? When Abraham Lincoln warned that the country could not endure half slave and half free, Stephen Douglas asked, why not? It had done so for generations. To understand why this precarious balance ultimately failed requires that we do much more than list the issues that divided Americans into hostile sections. Participants made it clear that war, secession, and slavery were inextricably interconnected. But there is always more to learn about why so many decent people were willing to kill for what they believed.

- [1] Diary entry for March [between 11 and 15], 1861, in C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 25.

- [2] Gideon Welles to My Dear Sir, October 16, 1861, Gideon Welles Papers, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, CT.

- [3] Quoted in James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 273.

- [4] “First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln,” The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp (accessed October 13, 2014).

- [5] Thomas H. Clay to John J. Crittenden, January 9, 1861, in Mrs. Chapman Coleman, ed., The Life of John J. Crittenden, with Selections from His Correspondence and Speeches, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1873), 2:253.

- [6] Quoted in Harold Holzer, Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter, 1860-1861 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 178.

- [7] “First Inaugural Address.”

- [8] Quoted in James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014), 26.

- [9] “Republican Party Platform of 1860,” The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29620 (Accessed October 13, 2014).

- [10] “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp (Accessed October 13, 2014).

- [11] “Georgia Secession,” Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_geosec.asp (Accessed October 13, 2014).

- [12] “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union,” Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_missec.asp (Accessed October 13, 2014).

- [13] William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 3.

- [14] For an excellent discussion of these important what-if questions about the election, see the Appendix entitled “1860 Election Scenarios and Possible Outcomes” in Douglas R. Egerton, Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election That Brought on the Civil War (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

- [15] Quoted in Francis Curtis, The Republican Party: A History of its Fifty Years’ Existence and a Record of its Measures and Leaders, 1854-1904, 2 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 1:189.

- [16] Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress, to the People of the United States ([Washington, DC]: Towers, Printers, [1854]), 1.

- [17] National Era, June 1, 1854.

- [18] Paul S. Preston to Jackson Woodward, January 2, 1850, Preston-Woodward Correspondence, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

- [19] Cong. Globe, 35th Cong., 2d Sess., appendix, 190 (1858).

- [20] Charles Sumner, The Crime Against Kansas. The Apologies for the Crime. The True Remedy. Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, in the Senate of the United States, 19th and 20th May, 1856 (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1856), 5.

- [21] Quoted in Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 347.

- [22] Quoted in Lorman A. Ratner and Dwight L. Teeter, Jr., Fanatics and Fire-eaters: Newspapers and the Coming of the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 52.

- [23] Opponents of the Lecompton Constitution often used the “swindle” term to denounce it. For one example of its use in Congressional debate, see the remarks of Massachusetts Republican Henry Wilson in the Cong. Globe, 35th Cong., 1st Sess., 499 (1858). For Douglas’s opposition to Lecompton, see especially ibid., 15-18.

- [24] Quoted in Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), 77.

If you can read only one book:

Levine, Bruce. Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of Civil War. New York: Hill and Wang, 1992.

Books:

Ashworth, John. The Republic in Crisis, 1848-1861. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Bonner, Robert E. Mastering America: Southern Slaveholders and the Crisis of American Nationhood. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Bowman, Shearer Davis. At the Precipice: Americans North and South during the Secession Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Cooper, William J. We Have the War Upon Us: The Onset of the Civil War, November 1860 – April 1861. New York: Alfred Knopf, 2012.

Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

Egerton, Douglas R. Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election That Brought on the Civil War. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2011.

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Fehrenbacher, Don E. The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press 1995.

Forbes, Robert Pierce. The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery & the Meaning of America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Freehling William W. The Road to Disunion, Volume 1: Secessionists at Bay, 1776-1854. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

———. The Road to Disunion, Volume 2: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Huston, James L. Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Mason, Matthew. Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Morrison, Michael A. Slavery and the American West: The Eclipse of Manifest Destiny and the Coming of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Oakes, James. The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War. New York: W. W. Norton, 2014.

Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

Richards, Leonard L. The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Rugemer, Edward Bartlett. The Problem of Emancipation: The Caribbean Roots of the American Civil War (Antislavery, Abolition, and the Atlantic World). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

Shelden, Rachel A. Washington Brotherhood: Politics, Social Life, and the Coming of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Varon, Elizabeth R. Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Woods, Michael E. Emotional and Sectional Conflict in the Antebellum United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Organizations:

Society of Civil War Historians

The SCWH is among the leading professional organizations for historians of the Civil War era of all types. The organization hosts a biennial conference and has adopted the Journal of the Civil War Era as its official journal.

Web Resources:

This website provides links to numerous primary source documents related to the sectional conflict and the coming of the Civil War.

Run by the National Park Service, this site offers a brief overview of Civil War causation and links to pages on historical sites of interest related to the coming of the war.

Furman University’s Department of History has organized this helpful site, which provides scores of editorials related to Bleeding Kansas, the caning of Charles Sumner, the Dred Scott case, and John Brown’s raid.

Hosted by the Civil War Trust, this website features teacher resources, including lesson plans, related to the Civil War. “The Gathering Storm” offers an online exhibit and lesson plans for all grade levels related to the coming of the Civil War.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History offers a “Civil War 150 Multimedia” page that includes podcast videos related to the causes, course, and consequences of the Civil War. Videos related to Civil War causation cover topics such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Dred Scott decision, Lincoln’s inauguration, and African American abolitionists.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.