Cavalry Raids

by Scott Thompson

More so than infantrymen, Civil War cavalrymen displayed the nineteenth-century values of glamor, adventure, endurance, chivalry, and courage. Contemporary observers and postbellum writers used colorful, romantic language to extol cavalrymen as uniquely skilled and brave warriors. Traditionally, the cavalry wing of a military force performed such duties as reconnaissance, scouting for the enemy’s location and strength, protecting its own flanks, and trying to outflank the enemy. Yet, due to their military effectiveness and cultural image, Civil War armies also sent their cavalry forces on separate, detached operations called raids. During these independent military actions, cavalry units rode behind enemy lines while relying on stealth. Raiders disrupted enemy supply lines, captured enemy commanders and forts, cut communication lines, destroyed railroads, caught enemy soldiers by surprise, battled gunboats, consumed enemy resources, and terrorized civilians. Due to their daring, destructive raids, the war’s Confederate cavalry commanders gave the Union Army some of its most acute headaches. While less prominent until the midpoint of the war, Union cavalry raiding disrupted the Confederate war effort as well. The effectiveness of cavalry raiding for either side in the Civil War depended on the time period. With the help of its raiding activities, early in the conflict, the Confederate Army’s cavalry forces proved superior to Federal horsemen. However, by 1863, Union cavalrymen caught up. They shifted from being a small, incompetent body of troops that merely supported the infantry to a large, effective force with more autonomy on the battlefield and behind enemy lines. In the Eastern theater J.E.B. Stuart, Wade Hampton and Turner Ashby were the most successful Confederate cavalry raiders, while George Stoneman, Hugh Kilpatrick, Philip Sheridan and George A. Custer were the most successful Union cavalry raiders. In the Western theater cavalry raids were more about guerilla warfare than support for conventional military operations Various small Union cavalry units fought as Jayhawkers in Kansas and Missouri and counter-guerilla raiders in Arkansas and West Virginia while Confederate guerillas and raiders were led by more famous men such as William Quantrill, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and John Hunt Morgan. Cavalry raids in particular and irregular warfare in general helped turn the Civil War from a limited conflict that protected property to a hard war in which both sides destroyed property and engaged in a cycle of reprisals. The major armies on both sides used cavalry raids to weaken the enemy during campaigns as well as to crush the will of the enemy to keep fighting. In those parts of the South with divided political loyalties, cavalry raiding became a central method of waging local and regional civil wars. With raiders fighting in both major campaigns and isolated guerrilla conflicts, they blurred the boundaries between conventional and unconventional warfare.

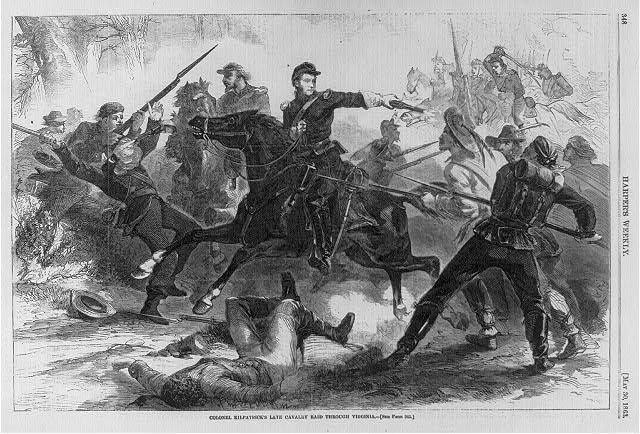

Colonel [Hugh Judson] Kilpatrick's late cavalry raid through Virginia, Harper's Weekly, 1863 May 30.

Picture Courtesy of: The Library of Congress.

American warriors possessing a unique military and cultural reputation during and long after the Civil War were those cavalrymen who fought primarily through raids. More so than infantrymen, Civil War cavalrymen displayed the nineteenth-century values of glamor, adventure, endurance, chivalry, and courage.[1] Contemporary observers and postbellum writers used colorful, romantic language to extol cavalrymen as uniquely skilled and brave warriors.[2] Before the use of gasoline-powered vehicles in warfare, for centuries, the image of the warrior riding a strong, fast-moving animal struck fear into the unmounted enemy who became the target of a cavalry attack. Traditionally, the cavalry wing of a military force performed such duties as reconnaissance, scouting for the enemy’s location and strength, protecting its own flanks, and trying to outflank the enemy.[3] Yet, due to their military effectiveness and cultural image, Civil War armies also sent their cavalry forces on separate, detached operations called raids. During these independent military actions, cavalry units rode behind enemy lines while relying on stealth. Raiders disrupted enemy supply lines, captured enemy commanders and forts, cut communication lines, destroyed railroads, caught enemy soldiers by surprise, battled gunboats, consumed enemy resources, and terrorized civilians. At times, raiders dismounted and fought as infantry. They fought with carbines, repeating rifles, and revolvers, weapons that could be fired more rapidly than the muskets of infantrymen. Cavalry raids blurred the boundary between conventional and irregular warfare. Due to their daring, destructive raids, the war’s Confederate cavalry commanders gave the Union Army some of its most acute headaches. While less prominent until the midpoint of the war, Union cavalry raiding disrupted the Confederate war effort as well.

Studying cavalry raids is essential to understanding the Civil War’s character, trajectory, and duration. Writing about an assortment of Confederate cavalry raids in the early twentieth century, aging United Confederate Veterans president Bennett Henderson Young contended that the role of cavalry forces proved so crucial that they ultimately both extended the Confederacy’s lifespan and brought on Union victory sooner than if they were not present.[4] A concurring view comes from scholar Virgil Carrington Jones. According to him, the “gray ghosts and rebel raiders” of northern and western Virginia delayed Union victory in the war for almost a year.[5] The evidence proves the effectiveness of cavalry raiding during the Civil War. Yet, the Union cause also greatly benefitted from its own raiders. Cavalry raiders not only had acute military importance, but also possessed cultural significance. These figures won the enthusiastic confidence and loyalty of their troops, psychologically scarred Americans with real and imagined attacks on cities, and later assumed prominent places in the postbellum southern Lost Cause mythology and in northern memory as romantic heroes.

The effectiveness of cavalry raiding for either side in the Civil War depended on the time period. With the help of its raiding activities, early in the conflict, the Confederate Army’s cavalry forces proved superior to Federal horsemen. Scholars have noted that southerners entered the war more skilled in horsemanship and weaponry than their northern counterparts.[6] Southerners tended to grow up learning how to both ride horses and use firearms, skills which proved useful during cavalry raids. Confederate raiders often continued a military tradition dating back to the American Revolution. Their ancestors likely had served with Francis Marion’s guerrillas and the dragoons of the U.S-Mexican War. However, by 1863, Union cavalrymen caught up. They shifted from being a small, incompetent body of troops that merely supported the infantry to a large, effective force with more autonomy on the battlefield and behind enemy lines.[7] The biggest cavalry engagement of the war, the Battle of Brandy Station of the Gettysburg Campaign, illustrated this shift when Union cavalrymen first acted as an offensive force against J.E.B. Stuart’s Confederate horsemen. They began demonstrating that they could disrupt and chase enemy infantry and cavalry.

Eastern Theater

Throughout the conflict, cavalry raids shaped the Confederacy’s approach to the Eastern Theater. The Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry forces under J.E.B. Stuart repeatedly harassed the Army of the Potomac in the war’s early years. As the Union Army struggled to resist his command, Stuart’s raids behind Union lines inflicted damage on Federal supply and communication lines, acquired important intelligence for Lee, and destroyed property worth millions. Stuart’s operations ultimately transformed cavalry into a fighting unit that could harass the enemy autonomously and separate from the main infantry force.[8] While the Union cavalry forces eventually attained the same status, the Confederates did so first. Like Major General Phillip Henry Sheridan did later in the war for the Union Army, Stuart’s raids strengthened the regular Confederate Army under Robert E. Lee, earning him a large amount of respect among comrades and enemies alike.

The Chickahominy raid of June 1862 stands out in General Stuart’s Civil War career. It is one of the more notable examples of cavalry raids helping conventional military campaigns. During the Peninsula Campaign, Stuart warned that rather than fight defensively, the Confederates needed to attack before the numerically superior Yankees did so. Lee thereafter enlisted his cavalry chief to break a stalemate between the two armies through a northward strike around the Union’s right flank. What resulted was the Army of Northern Virginia’s first major independent cavalry operation. In the early morning hours of June 12, the twelve hundred raiders moved along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. Guided by scouts including John Singleton Mosby, the column shifted west towards the Union-occupied Shenandoah Valley. The raiders encountered a force from the 5th and 6th U.S. Cavalry regiments located on the path to Major General George Brinton McClellan’s supply hub. When the two sides clashed, the mounted Confederates fired at the Union troops fighting on foot. Finding themselves outnumbered, the Federals retreated from screaming enemy soldiers. The U.S. regulars regrouped and formed a battle line at a road junction near Old Church. With the 9th Virginia charging in the vanguard, the Confederate raiders’ horses, sabers, and pistols crashed into the enemy line. A chaotic hand-to-hand fight ensued. As Confederates continued to arrive, the Union line collapsed. The Federals, with over a dozen casualties, retreated; the Confederates realized that McClellan’s flank was now vulnerable. While Lee had been skeptical of this last phase of the raid, Stuart’s popular support among the rank-in-file and his desire to devastate the Union Army while it was off-guard drove the cavalry chief to complete the raid with an encirclement. As Stuart’s raiders rode by at a great rate of speed to Tunstall’s Station that evening, uncoordinated Union cavalry and infantry pursuers struggled to keep up. Along the way, the raiders assaulted a Union camp, intercepted supply wagons, sacked a Federal supply depot, and severed communication lines before pushing ahead. After crossing the Chickahominy River, the exhausted raiders rode back to Confederate lines by June 15. At a small cost of only one officer killed, several wounded, and the loss of a single piece of artillery limber, the Chickahominy raid had gathered crucial intelligence, destroyed Union military resources, and had captured 164 prisoners and 250 animals. Once back at headquarters, a delighted General Lee congratulated Stuart. Afterward, the Confederate military, government, and press extolled the raid. Armed with the intelligence the raid had gathered, Lee thereafter launched an offensive on the Union Army, one that contributed to the major Confederate victory in the Peninsula Campaign. At times, cavalry raids provided essential intelligence for Civil War armies.[9]

Stuart’s subsequent cavalry raids added to the Confederacy’s eastern successes in late 1862. After the Battle of Antietam, Lee sent Stuart to strike the railroad at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a line on which George B. McClellan’s Union forces depended. The destroyed railroad track and burned warehouses the raiders left behind them as they rode back to Virginia gave the Confederacy a morale boost and gave a crushing blow to Union spirits. As historian Ted Alexander argues, the Chambersburg Raid ultimately helped terminate McClellan’s military career.[10] During the lead up to the Battle of Fredericksburg, Stuart’s cavalry performed not only flank protection, scouting, and picketing operations, but also additional raiding that greatly disrupted the Union’s already failed efforts. Though possessing a low opinion of the fighting style, Stuart subordinate Brigadier General Wade Hampton III launched a two-hundred-strong attack on the Union rear on a cold day in late November 1862. Near Falmouth, the Confederate raiders attacked pickets, wounding several and capturing eighty-two. Hampton’s raid angered Union commanders while earning praise from his superiors for his “daring, stealth, and enterprise.”[11]

During the remainder of the Fredericksburg campaign, Stuart and Hampton conducted additional raids that added to the havoc wrought on the Union soldiers. In mid-December, Hampton’s men struck a supply depot before ransacking warehouses, destroying communication and supply lines, and capturing hundreds of Union personnel. A raider later told his wife that also among the plunder were “all the good things you could think of,” including cigars and champagne.[12] On December 26 and 27, Stuart led an assault on the Telegraph Road with a column of eighteen hundred riders which stretched for two miles. This latest raid aimed to weaken the Army of the Potomac by diverting part of it away to resist the cavalry threat. The Confederate force attacked the road from multiple sides. Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee’s Confederates seized every single wagon of a Union column. Federal defenders retreated at the sight of Stuart’s force. After enjoying a string of successes, the Confederates encountered difficulties when they moved towards Dumfries. The Federals held the garrison with a superior force and had removed stores to prevent Stuart raiders from capturing them. After expending artillery ammunition, Stuart decided to bypass the town. Meanwhile, Hampton easily routed Pennsylvania cavalrymen, taking them by surprise as they enjoyed a holiday dinner but attacking too soon to cut off their retreat. Responding to news that a large Federal cavalry force was approaching, Stuart directed his men to prepare for an ambush. Dismounted Confederates covertly watched the Union troops approach from concealed positions before rushing forward and forcing them to retreat “like sheep,” as one Virginian described it, after several minutes of combat. The Confederates inflicted sixty casualties. Stuart’s raiders later headed north to hit the Orange and Alexandria railroad. At one of the track’s stations, the Confederates listened with joy to news of their raid on the telegraph. Before cutting the wire and concluding the raid, Stuart complained to a Union quartermaster general about the poor quality of their captured mules. The Confederates returned to camp near the Rappahannock by New Year’s. Thus, as raiding did throughout the conflict, Stuart’s involvement in this mode of warfare during the winter of 1862/1863 damaged the enemy physically and psychologically. Also, these raids had cemented the reputation of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Cavalry Division as a force to be reckoned with.[13]

During the early period of the war, Brigadier General Turner Ashby distinguished himself as a preeminent commander of northern Virginia’s Confederate cavalry raiders. Ashby’s Rangers followed an evolution typical of other raiders not completely attached to the regular army; starting out as partisan cavalrymen in the early part of the war in the Shenandoah Valley, they became regular cavalrymen before returning to irregular warfare. With both armies trading control over the Valley and launching raids to secure the overall border region of northern Virginia, Ashby’s cavalrymen formed one of the bulwarks of Confederate authority in the area. Though a component of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, Ashby’s command operated as a partisan unit tasked with patrolling the Valley independently. As raiders, Ashby’s forces operated behind enemy lines, ambushed the enemy, and fought hand-to-hand with revolvers and bowie knives. Due to his raids, Ashby represented various virtues—chivalry, honor, horsemanship, home defense, and warrior skills—associated with the Shenandoah Valley. Thus, northern Virginian Confederates painted the brigadier general as a romantic hero derived from literature. His raids helped Valley residents cope with the war’s violence by crafting a Confederate cause of national independence and home and family protection. When irregular warfare threatened chivalry and honor with bloody disorder, Ashby’s romantic persona resolved this contradiction. His cultural image became so legendary that stories circulated about him supernaturally appearing and disappearing, as well as defeating five hundred Union cavalrymen single-handedly. What helped fuel his legend was an incident during a raid on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad near Cumberland, Maryland, in late June 1861. When the Federals wounded and stole from his brother Richard, he recruited ten men and led them on a knife charge that broke the Union line. However, his desire for personal glory and his aversion to organizing his partisan raiders fostered ill-discipline in the ranks and prevented them from sufficiently defeating Union forces. When they once proved unable to pursue retreating Federals, Ashby’s superior, Stonewall Jackson, fumed. In June 1862, Federal troops killed Ashby during a charge near Harrisonburg, after which his men struggled adapting to conventional warfare. Following the war, Turner Ashby became part of the Lost Cause pantheon, representing the postbellum southern notion of Confederate bravery.[14]

After spending the war enduring continuous Rebel raids, by the 1863 turning point in the war, the Union Army sent its own raiders on operations attacking enemy communication and supply lines.[15] Confederate personnel now found themselves hampered by enemy raiding on their troops and supplies within their own lines. Also, by the latter part of the war, Confederate raiders found themselves weakened by shortages in firepower, supplies, and horses.[16] In 1864 and 1865, Union cavalry forces in general and cavalry raiders in particular had become what one scholar contends was “probably the most formidable dragoon force in the world.”[17]

The Army of the Potomac often sent its cavalry forces on raids against the Army of Northern Virginia and the Rebel capital. Often, the Confederates successfully resisted Federal raids; at other times, raids proved so successful that the Union cause received morale boosts. As the Federals struggled to turn the tide of the war following a string of Rebel victories in 1862 and early 1863, commanders realized that cavalry raiding offered an effective weapon to accomplish this goal. Also, since the issue of malnourished and dying prisoners of war in Confederate prisons drew widespread condemnation in the North, Federal leaders were also committed to liberating them via cavalry raids. The hard war aims of these raids accompanying the liberation attempts in turn frightened the Confederacy.

Following the devastating Union defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862, new Army of the Potomac commander Major General Joseph Hooker paved the way for Union cavalry raiding in the eastern theater. After Hooker ended infantry command of the cavalry forces and the reorganized Federal riders defeated the enemy at Kelley’s Ford in early 1863, the Army of the Potomac launched its raiding war. That May, Hooker ordered Major General George Stoneman’s cavalrymen to ride as an independent unit around Lee’s army and strike its communications and supply lines. Kelley’s Ford and the Stoneman Raid gave the Federals a morale boost. While this raid inflicted minimal physical destruction, it sent a psychological message by demonstrating that the Federals could move around the entire Army of Northern Virginia and threaten Richmond. Not only were Federal cavalry forces improving in conventional operations; they also now forced the Confederate Army to endure more irregular warfare as it tried to defend its capital.[18]

Richmond was a major target of Union cavalry raiding plots between 1863 and 1864. Such operations illustrate the extent to which cavalry raids spread fear and anxiety along with tangible destruction. In the fall of 1863, the Richmond press reported on an aborted plot in which prisoners of war would revolt and pave the way for a Yankee cavalry raid that would set fire to the capital’s infrastructure. Civil War-era cavalry raids had a cultural importance in that they injected frightening images in American minds regarding what these operations could potentially do. Several months later, as both armies sat in winter quarters, Union Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler and Brigadier General Isaac Jones Wistar planned an actual raid that would have committed the above actions plus destroy Rebel entrenchments and capture Confederate leaders including President Davis. Meanwhile, the rest of the army would keep Lee’s army engaged. Yet, when Wistar’s cavalry launched this raid in early February 1864, a heavily defended bridge persuaded the Union commander to abandon the attempt to attack Richmond. Like earlier alleged plots, this one spawned alarming newspaper articles about how it also sought to assassinate Davis. The hysteria enveloping Richmond as news of this planned raid poured in also caused Confederate authorities to arrest a German banker for allegedly trying to help Wistar. However, civilian judges dismissed the case for lack of evidence. Between the end of February and early March 1864, and with the personal approval of President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton, Major General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick led a raid on Richmond attempting to free Union prisoners once again and to issue Lincoln’s amnesty proclamation to citizens. Like previous attempts, this one failed in the face of Confederate defenses, this time with a large casualty rate. The Confederate press brought attention to written instructions retrieved from one of these casualties that the Federals once again sought to sack the capital and murder Confederate political leaders. Northern Republican praise for the planned raid in newspapers drew condemnation from the northern Democratic and Confederate press. Union officials denied the reports’ validity publicly but confirmed them in personal correspondence. The two raids on Richmond, like others during the Civil War, intensified the level of violence. The Confederate press used them to deflect blame for the Fort Pillow massacre, and more so than before, Americans decried “black flag” warfare (war without quarter). Whether a cavalry raid succeeded in its aims at all sometimes proved irrelevant; the mere planning of one sparked fears, desires for revenge, and exaggerated rumors.[19]

The Eastern Theater’s late-war campaigns witnessed continued Union reliance on cavalry raids. During the Union Army’s 1864 campaign against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, newly minted General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant ordered Phil Sheridan’s cavalry forces to strike the enemy’s cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart near Richmond, after which they would resupply and rejoin the main army. Frustrated by an earlier engagement that saw Federal soldiers become bogged in a traffic jam before withdrawing, Sheridan was eager for permission to assault Stuart in mid-May. The U.S. commander granted Sheridan and his 10,000 men independence. The raiders formed a column that slowly rode to Hamilton’s Crossing and down the Telegraph Road. Stuart’s 5,000-strong force, consisting of a horse artillery unit and three brigades, detected the raid and left Lee’s army in Spotsylvania to protect Richmond. Though already outnumbered, Stuart divided his men and struck the Federal rear by surprise. The New Jersey and Pennsylvania regiments holding the rear repulsed and counter-attacked the Confederates, driving them from the field. During a moment in the fight, carbine fire emptied dozens of saddles. Major General George Armstrong Custer’s Michigan Brigade played a supporting role in this raiding. After this skirmish, Custer’s men seized and destroyed cars filled with Confederate supplies and rations, and liberated prisoners of war. Sheridan next resumed the drive towards Richmond, hoping to engage the rest of Stuart’s men, who followed the Federals. On May 11, the Federal raiders and their Confederate enemies finally met for a decisive fight at Yellow Tavern, six miles from the Rebel capital. Sheridan immediately ordered his subordinates to attack. As one group charged the enemy flanks, the rear guard pushed back North Carolinians who delivered a volley of carbine and pistol fire. Riding with a loud yell and with guidance from their brigade commander, the raiders stormed the enemy artillery so effectively they turned the fight into a rout. In the course of this fighting, one Michigander shot General Stuart, who died of his wound the next day. Thus, Custer’s men proved essential. Yet, when Sheridan’s forces moved next towards Richmond’s outer defenses, they encountered land mines, rain, a damaged bridge, and strong Richmond defenses. Due to these conditions, Sheridan’s men withdrew. After incurring six hundred casualties and losing three hundred horses, the raiders returned to the Army of the Potomac to assist its flanking operations.[20]

Because of the U.S. Army’s campaigns, George Armstrong Custer became one of the Federal cavalry’s noted raiders. Nicknamed the Wolverines, his brigade had the reputation as one of the Union Army’s best cavalry units. While better known for his infamous death in the Indian Wars, Custer established himself as a military hero in the Civil War North.[21] Before the New Western History movement of professional historians which changed views of 19th century history, especially its focus on the atrocities of westward expansion, ruined Custer’s reputation, American culture honored him for his Civil War victories. Brigadier General James Harvey Kidd, an officer in and succeeding commander of Custer’s brigade, wrote of his military career after the war. Like Confederate veterans, Kidd spoke of his service as a chivalrous affair, complete with knights and their flashing sabers gloriously riding toward the enemy. Also, like his Confederate counterparts, Kidd idolized his commander as a model of courage and leadership, and willingly followed him in battle.[22]

Following the Battle of Cold Harbor, Sheridan launched a second raid that aimed to stop the Confederate cavalry from blocking the Federals’ move to Petersburg and to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad and James River Canal. Six thousand men participated. Due to the slow pace of the column, Wade Hampton, Stuart’s successor, reached the railroad’s Trevilian Station with his division first. Yet, this pace also enabled Sheridan’s raiders to burn enemy railroad tracks and to plunder civilian homes. The latter activity caused one officer to contend that raids had devolved into mere acts of thievery. Along the way, heat and guerrilla attacks partially slowed down the column. When the Federal raiders finally approached Trevilian on June 11, 5,000 Confederates rushed up to engage them. The combatants fought to a draw. Upon the Confederates’ decision to withdraw and join Lee, Sheridan deemed it best to return to his main army as well. As they did on the raid prior to the Trevilian Station battle, Sheridan’s raiders destroyed rail and ties. With Confederate skirmishers blocking their path, the raiders finished their return march while never attacking the river canal. Though this second raid proved less fruitful than the first, both fights plus conventional cavalry operations earned Sheridan popularity among the ranks in 1864.[23]

Phil Sheridan continued to rely on cavalry raids to assist his operations during the Valley Campaign of the fall of 1864, ones that demonstrated the consequences of unsuccessful raiding. In the days following the Union victory in the Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864, Sheridan sent subordinate Major General Alfred Thomas Archimedes Torbert on follow-up raids to cut off Major General Jubal Anderson Early’s escape. According to his mission, he needed to ford the Shenandoah River and to strike Confederate cavalry while riding down the Luray Valley. He next would re-cross the Shenandoah before reaching Early’s line of retreat near New Market. Meanwhile, Sheridan’s main force engaged Early head-on at Fisher’s Hill. While Sheridan triumphed a second time over Early, Torbert, to his surprise, ran into a strong line of Confederate horsemen whose flanks occupied a mountain and water banks, preventing the Federals from conducting any flanking maneuver. After a weak attack on the enemy position, Torbert retreated. To compensate for this failure, a fuming Sheridan demanded that his subordinate “whip that rebel cavalry or get whipped” himself.[24] Taking up this challenge, Torbert rallied his men during a successful assault on a detached Confederate cavalry force—Rosser’s Laurel Brigade—near Tom’s Brook. With the enemy fleeing, battered, and demoralized, Sheridan’s army began burning farms and destroying other property in order to deny northern Virginia’s Confederate forces of their breadbasket. Sheridan decisively defeated Early at Cedar Creek on October 19, after which the army entered winter quarters. Thus, the progress of a Civil War army’s campaign hinged on the success of its cavalry raiders.[25]

Western Theater

The Union Army’s western forces also used cavalry raiding to supplement their conventional operations. In the spring of 1863, during the Vicksburg campaign, the main Union force under Ulysses S. Grant pushed toward the prize city. To redirect Confederate attention, Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson’s Federal cavalrymen spent sixteen days riding down the Mississippi River from La Grange, Tennessee, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to sever railroad lines, burn supplies, and interrupt the enemy communication system. As it did in the East, commanders thought that the cavalry raids of the West offered conventional campaigns valuable assistance of the unconventional variety.

However, this particular raid represents an example of one that had more cultural than military importance. While many raiders became notable subjects of lore during or immediately after the war, Grierson and his men did not receive notice until Americans in the 1950s consumed media that told heroic stories of men on horseback. That decade, this raid became enshrined in American popular culture as readers and audiences could learn about it in Dee Brown’s Grierson’s Raid (historical monograph), Harold Sinclair’s The Horse Soldiers (novel), and John Ford’s The Horse Soldiers (film). Permeating throughout these works is the early Cold War American culture of domestic consensus and conformity. For example, characters form inter-sectional romances.[26]

The part of the western theater encompassing Kansas and Missouri produced a brutal irregular civil war within the national Civil War. Here, irregular operations such as cavalry raiding were not merely done in support of the regular army; they constituted the sole method of fighting in certain regions of Civil War America. While the image of the chivalrous, heroic Civil War cavalier dominated American culture, this western theater showed that cavalry raiding had a dark side. Along this western border, combatants waged a war of vengeance and atrocity that often refused to give quarter. With origins dating back to the Bleeding Kansas civil war of the 1850s between proslavery forces from Missouri and antislavery residents from New England, this region saw some of the war’s most ruthless cavalry raids.

The Union-affiliated Jayhawkers helped shape this bloody theater. One Jayhawker unit, Colonel Charles Rainsford Jennison’s Seventh Kansas Cavalry, fought to protect Kansas from Missouri’s Confederate guerrillas. To crush the rebellion as well as to exact revenge, these Federal raiders struck communities and farms in which pro-Confederate Missourians allegedly resided. Raids from 1861 witnessed the Jayhawkers plunder homes, steal property, free slaves, and kill civilians. Such tactics allowed raiding units to sustain themselves in the field without formal sources of supply. Due to their actions, these Kansans acquired a reputation as brigands and outlaws. As in the East, western raiding increased the destructive nature of the Civil War. The Jayhawkers thus became among the most marauding of Union cavalrymen.[27]

On the Confederate side of the Kansas-Missouri border war stood William Quantrill’s Missourian raiders. On August 21, 1863, this four-hundred-strong force launched one of the most violent raids of the war, the sack of pro-Union Lawrence, Kansas. Motivated by Confederate desire to avenge previous Jayhawker raids, this unsuspecting town constituted an attractive target for Quantrill because it represented a base of New England abolitionism. Quantrill’s horsemen torched and ransacked buildings in addition to killing one hundred and fifty civilians. After four hours of carnage, the raiders left the devastated town. A group of Federals briefly engaged Quantrill but failed to capture him on his way back to Missouri. Frustrated Union forces retaliated by continuing the cycle of retributive raids. Due to the atrocities committed during Jayhawker and Quantrill cavalry raids, the Kansas-Missouri war developed a reputation as a savage conflict, both of whose sides demonized the other. In the western theater, cavalry raids worsened the conflict’s level of violence and destruction.[28]

The wartime experiences of northern Virginia’s local communities illustrate the extent to which cavalry raids blurred the boundaries between conventional and unconventional warfare, as well as how cavalry raiding could become almost independent from the high command. In this region, both Union and Confederate forces utilized cavalry raids as one method of conducting irregular and counter-irregular warfare. In doing so, they tapped into the divided loyalties of the area, with small farmers, Scots-Irish ethnics, and Quakers siding with the Union and more prosperous planters and their neighbors supporting Confederate independence. To disrupt the enemy’s main operations, guerrillas—self-constituted bands of armed citizens fighting outside of a formal military structure—partisans—uniformed cavalrymen who fought with guerrilla tactics in independent units—and regular cavalry raiders—conventional cavalry forces that acted like partisans while temporarily detached from the main army—attacked supply lines and unsuspecting enemy troops with stealth and surprise behind enemy lines.[29] Whenever either type in one army wreaked such havoc, the other sent in partisan or regular cavalry forces on counter-irregular raids to try to neutralize the threat. In this localized war of raids and counter-raids, the Union Army created the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, Captain Richard R. Blazer’s Independent Scouts, and Major Henry Cole’s Maryland Cavalry, while the Confederate Army built a force that included Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Viers White’s Thirty-fifth Virginia Cavalry and Colonel John S. Mosby’s Forty-third Virginia Cavalry (Mosby’s Rangers).[30] Like Ashby’s raiders, the cavalry raiders northern Virginia spawned subscribed to an allegiance that combined abstract national causes and concrete local concerns. While these units formed under the guidance of the two national governments and official military structures, they served with a greater degree of discretion and autonomy than those raiders who fought near the front lines. The Thirty-fifth Virginia had the distinction of switching from a partisan command confined to the Potomac border area to a regular battalion attached to the Laurel Brigade that occasionally acquired permission to conduct independent raids.White’s Battalion twice raided West Virginia, during which it fought pro-Union guerrillas and home guards. Nicknamed the “Comanches,” White’s raiders also attacked the 6th New York Cavalry at Glenmore Farm in October 1862 and skirmished with Means’ Rangers and Cole’s battalion at Waterford in September 1863. The Loudoun Rangers attacked the Comanches in Waterford in August 1862, prompting the former to retaliate in September. Composed of men recruited from the same communities in northern Virginia, the two units subsequently clashed again at Catoctin Mountain. In September 1862, while on a raid, the 2nd Virginia Cavalry routed a combined force of Loudoun Rangers and Cole’s Maryland Cavalry at Leesburg.

The devotion of these units to fighting in a strictly raiding style became most clear when members of both the Loudoun Rangers and the Comanches at different times mutinied against their superiors’ attempts to transfer them to regular cavalry service. Further blurring the boundary between regular and irregular warfare, White and Means participated in the Gettysburg Campaign, and the former fought in the Valley Campaign and the Battle of the Wilderness. Unlike White’s raiders, Mosby’s Rangers were a product of the 1862 Partisan Ranger Act, through which the Confederacy officially authorized the formation of partisan raiders. They became the most notorious, destructive, and famous partisan raiding unit of the state, disrupting supply lines, masquerading as Union soldiers, and capturing high-ranking officers. Their popular support and effectiveness led several counties in northern Virginia to become known as “Mosby’s Confederacy.” Moreover, Mosby himself acquired the name “Gray Ghost.” Historian James Ramage argues that Mosby’s combat style resembled Carl von Clausewitz’s people’s war, whereby local civilians involve themselves in a military conflict.[31] Mosby’s Rangers routed the 1st Vermont Cavalry at Aldie in March 1863 and fought Cole’s Maryland Cavalry on several occasions. Both the Loudoun Rangers and Blazer’s Scouts conducted raids targeting Mosby’s partisans, with the former proving ineffective and the latter prompting counter-counter-irregular operations against it.[32] While Mosby’s overall damage to the Union Army proved limited, the partisan chief never lost control over his base of operations. Yet, to combat the threat posed by all Rebel raiders, the Union Army needed to devote more manpower and resources behind the front, helping to offset its numerical and industrial advantage over the Confederate Army.

Joining northern Virginia, other parts of the Civil War South saw operations that fused regular and irregular combat, took the form of localized and regional civil wars, and/or involved the United States military recruiting loyal white southerners. In the spring of 1863, following the admission of the new state of West Virginia to the Union, cavalrymen from Confederate Virginia launched a raid with military and political goals; strike the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, recruit men, seize animals for Lee’s army, and liberate northwestern Virginia from Federal rule. This Jones-Imboden Raid wreaked moderate havoc on the region’s infrastructure and resources and used speed to overcome a large numerical disadvantage. However, it intensified Unionist sentiment and prompted the Federals to strengthen their forces in the state.[33]

When Confederate guerrillas plagued Arkansas by repeatedly attacking and frustrating Union troops, counter-guerrilla raiders emerged. Colonel Marcus LaRue Harrison’s First Arkansas Cavalry (U.S.), which military historian Robert Mackey deems "the most successful of the Union counterguerrilla units" in the state, hunted down bushwhackers across its northern region.[34] These raids helped defeat the guerrillas militarily. Tennessee’s Unionists formed almost two dozen mounted regiments. These horsemen launched raids late in the war behind enemy lines against Confederate supplies in surrounding states. They furthermore assisted northern Union forces in rooting out Confederate irregulars in their home state. The need for counter-irregular raids owed to Confederate soldiers responding to the Army of the Tennessee’s defeats by altering the nature of their service. Among their nemeses were Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan and Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, the former dying at the hands of a bullet from a Unionist Tennessean and the latter devastating home-grown Union cavalry raiders. As the Union adopted the hard war approach, Tennessee’s Union raiders burned the homes and barns of secessionists. As in Virginia and Arkansas, Tennessee’s Unionist cavalry raiders provided the Federals with essential assistance in combating Confederate cavalry raiders across the regular-irregular spectrum.[35]

In the western theater, the Confederate cavalry raiders of Forrest and Morgan also obscured the regular-irregular warfare boundaries and wreaked havoc on Union operations. While sometimes as successful as Stuart in the East, these two commanders mostly raided independently from the regular Confederate military. Their forces destroyed millions of dollars in Union supplies and miles of Union transportation infrastructure, and captured thousands of Federal rear-guard soldiers. Their successful raids boosted Confederate morale in the western theater as well as nationally. Georgia Governor Joseph Emerson Brown viewed the two cavalry leaders as saviors who had restored “the days of chivalry.” Brown added that they therefore should serve as a model for other Confederate states, one that reenacted the American Revolution’s popular resistance.[36] However, Confederate raids in Kentucky and Tennessee also convinced the Federals to improve their horsemen’s training to match them with the enemy’s superior ones. The raids of this new Union cavalry targeted Forrest and Morgan, exhausting the enemy and killing irreplaceable Confederate horses. These counterraids joined with blockhouses and gunboats to weaken Confederate raiding in the western theater by 1863 and 1864. Yet, Kentucky’s Unionists hoped in vain for an increase in Federal troops to secure the state from Confederate raiders and other irregulars.[37]

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s career with raiding has combined with his founding of the Ku Klux Klan, slave trading, and involvement in the Fort Pillow massacre, making him a controversial figure. While conservative white southerners historically lionize him as a Confederate knight, the rest of American culture condemns the cavalry commander. Earning the nickname Wizard of the Saddle, Forrest differed from Morgan in that his raiding, rather than being fully independent, at times cooperated with regular forces. Forrest’s raiders developed a reputation on the Union side as marauders but viewed themselves as standard cavalrymen. In one raid from March and April 1864, Forrest’s cavalry tore through western Tennessee and Kentucky. Those fighting under Forrest also at times functioned as the counter-irregular form of raiders. When bands of white southern Unionists hunted down Confederate forces, plundered secessionist communities, and murdered enemies, Forrest attempted, with limited success, to root them out and turn them over to the Confederate justice system.[38]

John Hunt Morgan additionally has gained a scholarly and popular reputation for being an effective cavalry commander. Acting independently of the regular Confederate Army and aiming to protect pro-Confederate citizens in the border state of Kentucky, Morgan’s operations further demonstrated the ways in which cavalry raids added to the Civil War’s irregular aspect. He attacked Union pickets, disguised himself as a Federal commander, recruited civilians, disrupted Union transportation and communication networks, and destroyed Unionist civilians’ property. The press wrote of the “inscrutable guerrilla” in aggrandized fashion, despite his official status as a uniformed cavalry raider. So many Confederates rushed to become raiders under Morgan that one soldier identified the general as “the Marion of the War,” a reference to the revolutionary-era Patriot guerrilla leader Francis Marion.[39] As a result of these raids, Morgan slowed down Union operations and inspired partisans and guerrillas to conduct their own campaigns of irregular resistance against U.S. forces. His model of resistance against Union military occupation enjoyed such a high level of popular support that the Confederate government created units similar to his under the Partisan Ranger Act.[40] Under this act, Richmond formally authorized Confederate cavalry units to operate independently from the regular army and fight with the stealth and surprise required of raiding. The terror Morgan brought to Union forces during his successful raids caused him to become one of the Confederacy’s premier examples of a chivalrous cavalier and folk hero. Yet, his autonomous and harsh mode of raiding not only made enemies in the Union, but also invited a worried Confederate government to investigate his men’s actions.[41]

The highpoint of John Hunt Morgan’s career brought a one-thousand-mile horseback ride that crossed through the states of Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio for over three weeks in July 1863. Known as the Great Raid it was the longest cavalry raid of the entire conflict as well as one of the Confederate Army’s deepest penetrations into the North.[42] The hope was that in bringing the conflict directly to a war-weary northern populace, Copperheads would aid the raiders and the Union government would sue for peace. The raid thus demonstrates the tendency of cavalry raids to not just attack military targets, but also to terrorize civilians and to deliver psychological and political blows. Beginning with twenty-five hundred cavalrymen, the raid ended with three hundred fifty exhausted troops. The raid’s path of destruction left over sixty-five hundred northern homes and shops in ruins. As Morgan’s raiders plundered and burned their way through Union home territory, northern communities experienced the war firsthand rather than as a distant affair. Thus, in both the North and South, for some Americans, cavalry raids were the Civil War. Upon hearing cries from neighbors that the Rebels were on their way, panicked civilians hid their horses, money, and other valuables and/or armed themselves. However, while they feared large monsters, they instead saw hungry and thirsty young men and a well-mannered commander requesting food and water. After the war, Ohio citizens who lost property during the Morgan raid could apply for compensation from the state government.[43]

Riding behind enemy lines for a grueling month, the raiders needed to live off the land and confiscate what they could get to maintain ammunition, sustenance, and supplies. Along the way, the raiders fought state militiamen and fled pursuing regular Union cavalry. Yet, Morgan intentionally avoided large population centers and chose instead to ride close to the Ohio River in case a threat forced him and his men to cross back into the South. Twice the regular Federals met and clashed with the Confederate invaders. The Confederates’ seizure of almost every horse along the way deprived the Federals of fresh mounts. Captured at the end of the raid, Morgan escaped from an Ohio penitentiary. Though these northern areas never endured another invasion by a large Confederate force, the continued activity from other Rebel irregulars across the Ohio River kept them in a high state of anxiety.[44]

Six months later, in June 1864, Morgan launched a raid from Virginia back into Kentucky. In resuming his raiding career, Morgan highlighted the extent to which Americans at times identified hazards with this type of warfare. With new officers and enlisted men replacing the disciplined raiders of his previous unit, the operation devolved into a campaign of looting and pillaging. Morgan condemned those guilty, but the Confederate government dismissed him from command on the grounds that he constituted a mere robber. By the time of his death in an ambush three months later, Morgan’s fighting style lost favor among some Confederates. Even one of Morgan’s own men admitted to feeling ashamed for serving under him.[45]

Conclusion

It is a testament to cavalry raiding’s usefulness that its targets retaliated against it in a harsh manner by the war’s final year. Raiding in particular and irregular warfare in general helped turn the Civil War from a limited conflict that protected property to a hard war in which both sides destroyed property and engaged in a cycle of reprisals. Since the raiding brand of combat had the reputation of being uncivilized and illegal, its targets condemned it as unworthy of quarter and deserving of severe punishment. To punish civilians for aiding Confederate raiders like Mosby’s Rangers, frustrated Union forces launched the Burning Raid in late 1864. Riding across northern Virginia farms and communities, the Federals foraged, rounded up or slaughtered livestock, and burned buildings and crops. Thus, raiding shaped the larger, conventional side of the war, increasing its severity and potentially altering its timeline.[46]

As in the East, cavalry raiding became a component of the Union’s hard war strategy in the Western Theater. As the western Union armies marched across the Deep South over the war’s final months, Major General James Harrison Wilson launched a raid into Alabama in March and April 1865. Serving as a subordinate for much of the war, Wilson recommended sending cavalry forces “into the bowels of the South in masses that the enemy cannot drive back.”[47] With 14,000 mounted and dismounted men, Wilson rode towards Selma. With a frontal charge and flanking maneuver, Wilson shattered Nathan Bedford Forrest’s line of Confederates as well as an elaborate system of defenses outside of Selma. With the western Confederate forces weakened from such battles as Nashville, the Union’s increasingly notorious raiders helped deliver the knockout blow. From March to May 1865, General George Stoneman conducted a raid laying waste to infrastructure, capturing towns, clashing with enemy forces, and pursuing the remains of the collapsing Rebel military and government across two thousand miles of Confederate territory, mostly in the Upper South. As historian Chris J. Hartley points out, while Ulysses S. Grant envisioned the Stoneman Raid as a way to undermine a potential Robert E. Lee retreat, its ultimate result was merely to add further physical destruction to the conquered South.[48]

To fully understand the American Civil War, one needs to study the contribution of its cavalry raiders to the conflict’s military, social, and cultural history. The major armies on both sides recruited these warriors to weaken the enemy during campaigns as well as to crush the will of the enemy to keep fighting. In those parts of the South with divided political loyalties, cavalry raiding became a central method of waging local and regional civil wars. With raiders fighting in both major campaigns and isolated guerrilla conflicts, they blurred the boundaries between conventional and unconventional warfare. Moreover, the cavalry raider struck such fear in the hearts and minds of Americans that they took the smallest rumors of an impending raid seriously. Likewise, when the Federals or Confederates found a skilled raiding unit of their own, its members boosted civilian morale and became cultural icons. Overall, for many Americans, the threat or promise of a cavalry raid colored their entire Civil War experience.

- [1] Bennett H. Young, Confederate Wizards of the Saddle: Being Reminiscences and Observations of One Who Rode With Morgan (Boston: Chapple Publishing Company, 1914), xiv-xv.

- [2] Ibid., Foreword.

- [3] Laurence D. Schiller, “The Evolution of Union Cavalry 1861-1865,” in Essential Civil War Curriculum, (Blacksburg: Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, December 2012),http://essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/the-evolution-of-union-cavalry-1861-1865.html,accessed February 10, 2020.

- [4] Young, Confederate Wizards, xii.

- [5] Virgil Carrington Jones, Gray Ghosts and Rebel Raiders: The Daring Exploits of the Confederate Guerillas (New York: Henry Holt, 1956), vii.

- [6] Edward Longacre, Lee’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002), xi.

- [7] Young, Confederate Wizards, xxii; Schiller, “The Evolution of Union Cavalry 1861-1865.”

- [8] Thom Hatch, Clashes of Cavalry: The Civil War Careers of George Armstrong Custer and Jeb Stuart (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001), xi.

- [9] Longacre, Lee’s Cavalrymen, 85-95.

- [10] Ted Alexander, “Stuart's Chambersburg Raid,” in Essential Civil War Curriculum, (Blacksburg: Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, December 2012),http://essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/stuarts-chambersburg-raid.html, accessed February 10, 2020.

- [11] Longacre, Lee’s Cavalrymen, 160.

- [12] Quoted in Ibid., 163.

- [13] Ibid., 163-6.

- [14] Paul Anderson, Blood Image: Turner Ashby in the Civil War and the Southern Mind (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006).

- [15] Schiller, “The Evolution of Union Cavalry 1861-1865”.

- [16] Longacre, Lee’s Cavalrymen, xi.

- [17] Schiller, “The Evolution of Union Cavalry 1861-1865”.

- [18] Ibid.; Steven Z. Starr,The Union Cavalry in The Civil War, 3 vols. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979), 1:327-50.

- [19] Joseph George Jr., “‘Black Flag Warfare’: Lincoln and the Raids against Richmond and Jefferson Davis,” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 115, no. 3 (July 1991), 291-318; Emory M. Thomas, “The Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid—Part I,” in Civil War Times Illustrated, 16 (February 1978), 4-9, 46-48; Emory M. Thomas, “The Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid— Part II,” in Civil War Times Illustrated, 17 (April 1978), 26-33.

- [20] Edward G. Longacre, Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000), 263-76; Hatch, Clashes of Cavalry, 187-201.

- [21] Ibid., xii.

- [22] Eric Wittenberg, ed., At Custer's Side: Civil War Writing on James Harvey Kidd (Kent, OH and London: The Kent State University Press, 2001), xii-xiii, xv.

- [23] Longacre, Lincoln's Cavalrymen, 277-82.

- [24] Reports of Bvt. Maj. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert, November 1864 in United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 43, part 1, p. 431 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 43, pt. 1, 431).

- [25] Longacre, Lincoln's Cavalrymen, 307-11.

- [26] Neil L. York, Fiction as Fact: The Horse Soldiers and Popular Memory (Kent, OH and London: The Kent State University Press, 2001).

- [27] Stephen Z. Starr, Jennison’s Jayhawkers: A Civil War Cavalry Regiment and Its Commander (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993).

- [28] Thomas Goodrich, Bloody Dawn: The Story of the Lawrence Massacre (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991).

- [29] Robert Mackey, The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005), 5-11; Scott Thompson, “The Irregular War in Loudoun County, Virginia,” in The Guerrilla Hunters: Irregular Conflicts during the Civil War, Brian D. McKnight and Barton A. Myers, eds., (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 123-46.

- [30] For exceptional histories of these units, see Briscoe Goodhart, History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers. U.S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts) 1862-65 (Washington, D.C.: Press of McGill & Wallace, 1896); Frank M. Myers, The Comanches: A History of White’s Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Laurel Brig., Hampton Div., A.N.V., C.S.A. (Baltimore: Kelly, Piet & Co., Publishers, 1871); C. Armour Newcomer, Cole’s Cavalry, or Three Years in the Saddle in the Shenandoah Valley (Baltimore: Pushing and Company, 1895); James J. Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers (Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1895); Daryl L. Stephenson, Headquarters in the Brush: Blazer's Independent Union Scouts (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001).

- [31] James Ramage, Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singleton Mosby (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

- [32] Mackey, The Uncivil War, 107.

- [33] Darrell L. Collins, “The Jones-Imboden Raid,” in Essential Civil War Curriculum, (Blacksburg: Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, December 2012), http://essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/the-jones-imboden-raid.html, accessed February 10, 2020; O.R.,I, 25, pt. 2, 652-3; O.R., I, 25, pt. 1, 90-93, 104.

- [34] Mackey, The Uncivil War, 62.

- [35] James Alex Baggett, Homegrown Yankees: Tennessee's Union Cavalry in the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009).

- [36] Quoted in Daniel Sunderland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 223-4.

- [37] Mackey, The Uncivil War, 123-63; Ibid., 441-2.

- [38] Eddy W. Davison, Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2007); Sunderland, A Savage Conflict, 155-6, 442, 466.

- [39] Quoted in Sutherland, A Savage Conflict, 154-5.

- [40] James Ramage, Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1986), ix; Lester V. Horwitz, The Longest Raid of the Civil War: Little-Known & Untold Stories of Morgan's Raid into Kentucky, Indiana & Ohio (Indiana: Farmcourt, 1999), xix.

- [41] Ramage, Rebel Raider, ix-x.

- [42] Horwitz, The Longest Raid of the Civil War, cover sleeve.

- [43] Report of the Commissioners of Morgan Raid Claims to the Governor of the State of Ohio: December 15, 1864 (Columbus: Richard Nevins, 1865).

- [44] Horwitz, The Longest Raid of the Civil War, Preface; Sunderland, A Savage Conflict, 453-4

- [45] Sunderland, A Savage Conflict, 440-1.

- [46] Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, 320-1; For works on how the Union Army adopted and applied hard war strategy, see Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Towards Southern Civilians, 1861-1865 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Clay Mountcastle, Punitive War: Confederate Guerrillas and Union Reprisals (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009).

- [47] O.R. I, 39, pt. 3, 443.

- [48] Chris J. Hartley, “Stoneman's 1865 Raid,” in Essential Civil War Curriculum, (Blacksburg: Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, December 2012), http://essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/stonemans-1865-raid.html, accessed February 10, 2020.

If you can read only one book:

Longacre, Edward. Lee’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002.

Books:

Anderson, Paul. Blood Image: Turner Ashby in the Civil War and the Southern Mind. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Baggett, James Alex. Homegrown Yankees: Tennessee's Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Davison, Eddy W. Nathan Bedford Forrest: In Search of the Enigma. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2007.

Goodhart, Briscoe. History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers. U.S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts) 1862-65. Washington, D.C.: Press of McGill & Wallace, 1896.

Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Towards Southern Civilians, 1861-1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Hatch, Thom. Clashes of Cavalry: The Civil War Careers of George Armstrong Custer and Jeb Stuart. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Horwitz, Lester V. The Longest Raid of the Civil War: Little-Known & Untold Stories of Morgan's Raid into Kentucky, Indiana & Ohio. Indiana: Farmcourt, 1999.

Jones, Virgil Carrington. Gray Ghosts and Rebel Raiders: The Daring Exploits of the Confederate Guerillas. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1956.

Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000.

————. Lee’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002.

Mackey, Robert. The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

McKnight, Brian D. and Barton A. Myers. The Guerrilla Hunters: Irregular Conflicts during the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Mountcastle, Clay. Punitive War: Confederate Guerrillas and Union Reprisals. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Myers, Frank M. The Comanches: A History of White’s Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Laurel Brig., Hampton Div., A.N.V., C.S.A. Baltimore: Kelly, Piet & Co., Publishers, 1871.

Newcomer, C. Armour. Cole’s Cavalry, or Three Years in the Saddle in the Shenandoah Valley. Baltimore: Pushing and Company, 1895.

Ramage, James. Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singleton Mosby. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

————. Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1986.

Starr, Stephen Z. Jennison’s Jayhawkers: A Civil War Cavalry Regiment and Its Commander. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

————. The Union Cavalry in The Civil War, 3 vols. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979, vol. 1.

Stephenson, Darl L. Headquarters in the Brush: Blazer's Independent Union Scouts. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001.

Sunderland, Daniel. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Williamson, James J. Mosby’s Rangers. Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1895.

Wittenberg, Eric, ed. At Custer's Side: Civil War Writing on James Harvey Kidd. Kent, OH and London: The Kent State University Press, 2001.

York, Neil L. Fiction as Fact: The Horse Soldiers and Popular Memory. Kent, OH, and London: The Kent State University Press, 2001.

Young, Bennett H. Confederate Wizards of the Saddle: Being Reminiscences and Observations of One Who Rode With Morgan. Boston: Chapple Publishing Company, 1914.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.