Civil War Journalism

by Ford Risley

The press of the Union and Confederacy published millions of words on every aspect of the Civil War.

When the Union and Confederate armies faced one another across Antietam Creek on the morning of September 17, 1862, the Civil War was at a pivotal juncture. The Confederacy had capped a successful summer by defeating the Union at the Battle of Second Manassas and was poised to invade the North. General Robert E. Lee believed that if the Confederates could defeat the Federal forces at another major battle, then the North might be willing to begin peace negotiations. However, Lee did not count on the determination of Union soldiers to expunge previous defeats. By the end of the day, the Union army had turned back the Confederacy yet at a horrifying cost to both sides. Nearly 6,000 men were dead and another 17,000 wounded.

Journalists from both sides recognized that Antietam was perhaps the biggest news event of an already momentous war. Certainly George Smalley of the New York Tribune knew he had to get his story of the battle to his newspaper. Smalley had watched the battle unfold so close to the fighting that his horse had been hit by gunfire. He borrowed another horse and left the battlefield to ride thirty miles to the nearest telegraph office. He arrived early the next morning but discovered that the office was closed. When the telegraph operator arrived, Smalley sat down on a log by the office and wrote his story, handing sheets of paper to the telegraph operator one by one. His story was published in an extra edition.

While Smalley was beating his fellow Northern reporters, Peter Wellington Alexander of the Savannah Republican knew that readers would want perspective on the defeat. Alexander, who had shown his concern for the common soldier in earlier stories, was moved by the plight of Confederate troops, many of whom were hungry and ill-clothed. He minced no words in describing them. “A fifth of the troops are barefooted; half of them are in rags; and the whole of them insufficiently supplied with food. . . .” he wrote. “Since we crossed into Maryland, and even before they frequently had to march all day and far into night for three and four days together, without food of any kind, except such apples and green corn as they could obtain along the way.”[1]

The stories of Smalley and Alexander showed how much American journalism had changed in the past three decades. Whereas newspaper editors once had been content to let the news come to them, they now were aggressively covering a war. Not only were reporters expected to write their stories as fast as possible, but more demanding editors wanted news beyond what simply happened on the battlefield. Journalists with a skill for writing were not the only ones covering the war. Men whose talents lay in drawing and photography also for the first time extensively reported a war. At the same time, government and military officials wanted to make sure that what was reported did not reveal military information. Back at the newspapers offices, editors used their pens to express their views on a variety of war-related subjects.

On the eve of the war, the American press was a political, social, and economic force. The country’s approximately 3,700 newspapers were twice the number published in Britain and about one-third of all newspapers in the entire world. The great majority of publications were small weeklies. However, virtually every community of any size had a least one or two newspapers, and many larger cities had three, four, or more. Magazines also were becoming increasingly popular, in particular a new breed of illustrated weeklies. Seizing on the popularity of elaborate illustrations, the magazines packed each issue with pictures. Thus it was hardly surprising that the director of the U. S. Census of 1860 said that newspapers and periodicals “furnish nearly the whole of the reading which the greater number, whether from inclination or necessity, permit themselves to enjoy.”[2]

Changes in journalistic and business practices since the 1830s had made a significant impact on the country’s press, particularly in the country’s metropolitan areas. The introduction of the “penny press,” inexpensive publications aimed at a mass audience, changed newspapers, which for decades had largely been editorial tools of the country’s political parties. Led by publications in New York City, editors recognized that readers craved news: news that was essential, but also news that entertained. Publications in other big cities soon followed the penny press model.

At the same time, a technological revolution helped make the press into a truly mass media. The telegraph, invented in 1844, meant that newspapers for the first time could gather and report the news in a timely manner. The usefulness of the telegraph led to the development of the Associated Press, the first cooperative news gathering organization. The invention of new steam-powered cylinder presses made it possible for newspapers and magazines to reach a far larger audience. Thousands of copies of newspapers could be turned out in an hour. And thanks to the growth of the railroad, which by mid-century linked the north and south, east and west, newspapers could be distributed across the country. The New York Tribune’s weekly national edition had an eye-popping circulation of more than 120,000.

The press of the Union and Confederacy published millions of words on every aspect of the Civil War. Hundreds of reporters chronicled the fighting on land and at sea. Others reported news from the capitals of Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Virginia. They overcame numerous challenges, including uncooperative sources and the difficulty of getting their stories back to the newspaper. In the field, correspondents endured hardships and dangers. Several newsmen were killed covering the fighting and others were captured.

No standards existed for what constituted sound, thorough, and responsible journalism on the eve of the war. The special correspondents—“specials” as they were frequently known—were guided by their backgrounds, education, talent, and standards. Certainly they were a diverse group. While some had previous journalism experience, others included lawyers, teachers, clerks, bookkeepers, ministers, and at least one poet. Some were college educated while others had only rudimentary schooling. Not surprisingly, the overwhelming majority of correspondents were white men. A handful of women briefly reported during the war. Only one black man, Thomas Morris Chester of the Philadelphia Press is known to have been a correspondent for a daily newspaper.

In the field, correspondents generally lived like soldiers. In a letter to his editor, Samuel Wilkeson of the New York Times wrote: “The flannel shirt I have on I have worn five weeks. . . . Rails make my bed . . . . My jackknife is my spoon, knife, fork, and toothpick . . . .” A Southern correspondent described living conditions in reporting from the Confederate army. “Comforts of life are scarce,” he wrote. “Hard bread, water, molasses and bacon, very tough and indigestible, constitute our fare; a very hard plank and a pair of blankets serves as our bed. . . . We wash our own clothes, do our own cooking, and when rations give out, ‘beg, borrow, and steal.’ About three times a week we have the chills. . . .”[3]

Many of the accounts by correspondents honestly and faithfully chronicled the war. Tireless newsmen went to great lengths to report stories on deadline and displayed considerable enterprise to describe the war in all its facets. Many of the biggest battles, including Shiloh, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg, seemed to bring out some of the best work by correspondents on both sides. The stories not only provided comprehensive views of the battles but also dramatic passages and colorful anecdotes. Perhaps none was more dramatic than the battle of Gettysburg. The Boston Journal’s Charles Coffin graphically described the hand-to-hand fighting that took place during the famous charge by General George Armstrong Pickett’s troops. He wrote:

Men fire into each other’s faces, not five feet apart. There are bayonet-thrusts, sabre-strokes, pistol shots . . . oaths, yells, curses, hurrahs, shoutings . . . men going down on their hands and knees, spinning round like tops, throwing out their arms, gulping up blood, falling; legless, armless, headless. There are ghastly heaps of dead men. Seconds are centuries, minutes, ages; but the thin line does not break![4]

Enterprising reporters on both sides also produced human interest stories on a variety of subjects. After the battle of Second Bull Run, Southern correspondent Felix Gregory de Fontaine described the Confederate field hospitals thrown up after the fighting. “For nearly half a mile along the Warrenton turnpike, the forest presented a vast spectacle of human suffering,” he wrote. “Here were the various temporary division hospitals . . . .The operating tables consisted of piles of rails, covered only with a few rough boards . . . . Arms and legs were lying around the half dozen surgical altars. . . .” Additionally, correspondents who were outraged by mismanagement and poor treatment of the troops, reported on the problems. One story reported on the poor quality of shoes and clothing given to Confederate soldiers. Another exposed a quartermaster who stole from the army.[5]

On the other hand, numerous accounts mistakenly and, in some cases, irresponsibly reported the conflict. Reporters less concerned with the facts and more interested in rushing stories into print wrote damaging stories that hurt their side. Reporters were guilty of everything from sensationalism and exaggerations to outright lies and conjecture. Newspapers published reports of battles never fought. They accused commanders of a variety of mistakes and indiscretions without any evidence. An even more serious problem was stories printed in newspapers that revealed sensitive military information.

In addition to the correspondents employed by newspapers, the Associated Press employed a staff of correspondents with at least one at virtually every important point in the country. Many newspapers in the North, particularly smaller ones, relied heavily on the AP for news of the war. They published daily columns of telegraphic news, often on the front page. Southern editors tried various cooperative news arrangements before settling on what became known as the Press Association of the Confederate States of America or simply P.A. The Press Association’s superintendent hired correspondents to report from Richmond and Charleston, as well as the Confederacy’s largest armies. He admonished his newsmen in the importance of “securing early, full, and reliable” news. He also ordered that stories should be free of opinion and to not send “unfounded rumors as news.”[6]

People also wanted to see the news of the Civil War that they read about. A cast of artists and photographers provided the images. Never before had a significant event been captured pictorially so widely and provided to such a vast audience. Thousands of illustrations appeared in magazines and newspapers, and more than a million photographs were made. Most artists and photographers considered themselves reporters who worked with pictures instead of words. The best illustrations and photographs had a realism that captured the war in all its many faces.

The great majority of illustrations and photographs appeared in the North. Three illustrated weeklies published the sketches of full-time artists in the field. Cameramen made photographs that could not be published, but were turned into illustrations and shown in galleries. The South had fewer magazines and most closed because of insufficient manpower, supplies, and advertising. The South also had fewer photographers and most of them did not have the equipment, supplies, or financial wherewithal to record the war.

The most popular magazines were Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly. At the time, both were classified as newspapers because they reported current events. However, they emphasized material more common to magazines, chiefly features and illustrations. Their distinctive appearance and size made the publications immediately recognizable. The magazines regularly devoted as many as half of their sixteen pages in each issue to illustrations, many of them full page in size.

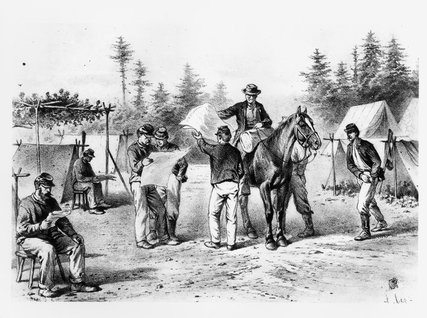

An estimated thirty full-time sketch artists covered the war for the magazines. Some had some formal training and their ranks included graduates of the Royal Academy of London and the National Academy of Design. Artists had varied experiences before the war. Several worked as book illustrators, others as designers and lithographers. A few were portrait and landscaper painters and at least one was a magazine cartoonist. The most prolific sketch artist was Alfred Waud, who sketched initially for the New York Illustrated News but switched to Harper’s Weekly. He not only made sketches of the most of the major battles in Virginia, but he also produced many memorable pictures of camp life.

With a haversack hanging on their hip and a sketchpad and pencils in hand, the artists were immediately recognizable in the field. They usually made pencil drawings for battle scenes but preferred crayon and charcoal for camp illustrations. Being a successful sketch artist not only required artistic talent but sharp observational skills and a good memory. Artist Theodore Davis described the qualities one should have: “Total disregard for personal safety and comfort; an owl-like propensity to sit up all night and a hawky stile of vigilance during the day; capacity for going on short food; willingness to ride any number of miles on horseback for just one sketch, which might have to be finished at night by no better light than that of a fire . . .”[7]

Publishing the illustrations was a complicated process. Working with a sketch provided by the artist, studio artists reproduced the sketch in reverse on blocks of wood. Engravers then cut away the bare white surface, leaving only the drawn lines in relief to be printed like type. Once completed, the blocks were bolted together to form a picture. Ten to fifteen engravers would be used to complete a single picture, and a two-page illustration could require as many as forty blocks. An electrotyped metal impression then was made from the blocks for printing on the high-speed rotary presses. Depending on how long it took for the sketch to arrive at the magazine, it could take anywhere from one to three weeks for pictures from the war to go from an artist’s sketch pad to the pages of a magazine.

Photographs could not be used in Civil War newspapers because a practical method of printing pictures on paper had not been developed. Even so, the photographers who covered the fighting did some of the best reporting of the war. Because of the long exposure time it took to make pictures, the majority of war photographs were posed. Individuals or groups were set up by the photographer and instructed to simply look at the camera and not move while their picture was made. The more skilled and creative photographers did more, capturing subjects when they were at ease. Cameramen were unable to photograph the fighting, so they made pictures of the aftermath: dead soldiers, wrecked equipment, devastated cities and countryside. Viewers saw the pictures in galleries where they could purchase copies. They also saw them in the illustrated magazines, which regularly turned the best photographs from major battles and campaigns into intricate drawings.

Less is known about the photographers who recorded the war. Many worked in obscurity, their names never attached to their pictures. Even with the dozen or so who have been identified only a few left behind any significant personal information. Many photographers had experience before the war either as portrait photographers or assistants. When the fighting began, they took advantage of the demand for portraits, making pictures of the new recruits for both armies. However, for many photographers their war experience ended there. Making pictures in the field simply was too difficult and expensive for most of them.

The best-known photographer when the war began was Mathew Brady. Brady had opened a daguerreotype studio in New York in 1844 and quickly established himself as one of the city’s leading portraits photographers. His lavishly appointed studio on Broadway was near the city’s finest hotels. He lured many of the best-known figures of the era from their hotels to his studio to have their portrait made. Business boomed and within ten years, Brady employed more than twenty-five workers, including camera operators, technicians, and finishers.

The ambitious Brady wanted to make a complete photographic record of the war. He hired a staff of talented photographers led by Alexander Gardner. Gardner and the other assistants took many of the best-known photographs of the war, including those from pivotal battles such as Antietam and Gettysburg. A few cameramen in the South also sought to capture images of camp life. J. D. Edwards and Ben Oppenheimer made widely distributed pictures of camp life in the South, but they were unable to continue the output.

Newspapers of the North and South did not simply report on the war. Editors used their editorial pages to comment on the progress of the fighting and on the conduct of leaders, both political and military. Newspaper editors in America had a rich history of brandishing the editorial pen and they did not stop simply because a war had enveloped the country. Their views were perhaps best expressed by the New York Times: “While we emphatically disclaim an deny any right as inhering in journalist or others to incite, advocate, abet, uphold or justify treason or rebellion; we respectfully but firmly affirm and maintain the right of the press to criticize freely and fearlessly the acts of those charged with the administration of the Government; also those of their civil and military subordinates. . . .”[8]

The topics of editorials and cartoons ranged widely. Issues relating to the fighting and its administration were far and away the most popular subjects, but editors and artists addressed economic, social, and diplomatic matters as well. Editors had no shortage of advice for the political and military leaders directing the war efforts. They also endorsed candidates at various levels of government. Issues of national interest received the most attention from editors. They also turned their pens on state and local subjects.

Both the Lincoln and Davis administrations had newspaper supporters that they could count on. Among the most loyal Republican publications were the Chicago Tribune, New York Times, Washington Morning Chronicle, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Springfield Republican. These newspapers supported the administration’s policies on virtually every issue. They beat the drum for war, exaggerating Union victories and minimizing Union defeats. And they repeated the message in editorial after editorial that the Confederacy could never be victorious. As was the custom for American presidents, Lincoln rewarded his friends in the press with patronage and political appointments. The president’s newspaper supporters also published pieces written by administration officials and even the president himself.

President Davis also had numerous supporters in the Southern press, notably the Richmond Enquirer, Charleston Courier, Augusta Constitutionalist, and Mobile Advertiser and Register. These newspapers faithfully supported the administration and repeatedly defended the president from critics. They praised the heroic efforts of soldiers and civilians, decried apathy and disloyalty, emphasized Union problems, and explained the consequences of defeat. Unlike Lincoln, Davis did not actively court the press or make himself available to reporters. And while the president had newspaper supporters, the administration did not have any publications that could be their editorial mouthpiece. Administration officials suggested securing a sympathetic newspaper to explain the wisdom of administration measures that were unpopular, but the president ignored the advice.

More than one hundred Democratic newspapers in the North sympathized with the Confederacy and opposed the war, among them the New York World, Chicago Times, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Detroit Free Press, Dayton Empire, Dubuque Herald, and Columbus Crisis. These Copperhead publications, as they were known, virulently opposed the war. They believed the southern states had a right to leave the Union. They also viewed slavery as a state issue and argued that only individual states had a right to eliminate it. When the governor of Ohio prepared to answer Lincoln’s call for troops, the Empire declared: “Governor Dennison has pledged the blood and treasure of Ohio to back up a Republican administration in its contemplated attack upon the people of the South . . . Does he promise to head the troops which he intends to send down South to butcher men, women and children of that section?”[9]

In the South, few editors dared not to support the Confederacy in its fight with the Union. Most had been outspoken supporters of slavery and they advocated any means of preserving the institution they believed was so vital to maintaining the South’s economy and way of life. However, that did not mean that editors could not be critical of the Confederacy’s leaders in the way that they prosecuted the war. Southern editors could be sharply critical of the Confederate government and, in particular, President Jefferson Davis. Among the leading editor who opposed the president on numerous occasions were Robert Barnwell Rhett, Jr. of the Charleston Mercury, Nathan B. Morse of the Augusta Chronicle & Sentinel, and John M. Daniel of the Richmond Examiner. It took only a few months for Daniel to be a staunch critic of Davis. By the fall of 1861, Daniel argued that several Confederate leaders would have made a better president. When R. M. T. Hunter left the cabinet, and Davis named the unpopular Judah P. Benjamin as secretary of state, Daniel claimed that Davis kept lesser men in his cabinet because he was “jealous of intellect.”[10]

An aggressive and outspoken press presented issues for the governments of the Union and Confederacy during the war. Newspaper correspondents for both sides were determined to report stories from the battlefield, but military and civilian leaders were just as determined to ensure they did not reveal critical information. And while editors wanted to voice their opinions on issues, political leaders wanted to ensure they did not hurt morale and the war effort. The result was censorship and newspaper closings on a scale never seen before during wartime, particularly in the North.

The attempts to restrict and control the press presented new constitutional issues. Although the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 had made it a punishable crime to criticize the federal government, the United States had never experienced broad censorship and courts had not ruled on issues of freedom of the press during wartime. Violence against the press was not unusual in nineteenth-century America, but it rose to an unprecedented level during the war as citizens and soldiers repeatedly sought to silence newspapers they considered disloyal, often breaking into the offices and wrecking the presses.

Few disputed the necessity of some press censorship during wartime, particularly a war that was fought entirely on American soil. But, in many cases, the restrictions imposed by both sides were arbitrary, hasty, and heavy-handed. Journalists protested the censorship rules they considered unreasonable, and they raged in editorials against the mob violence. However, with no real protection for freedom of expression in the mid-nineteenth century there was little they could do.

During the first year of the war administration of censorship in the North was passed from one department to another. It was initially under the Treasury Department, then transferred to the War Department, then to the State Department, and, finally, back to the War Department. Reporters and editors were understandably confused about the rules they had to work under. At the same time, Southern leaders also were taking steps to establish telegraphic censorship. Early in the war, the Confederate Congress approved a bill giving the president the authority to put government agents in telegraph offices to supervise the transmission of dispatches and to impose penalties of fines and imprisonment for anyone convicted of sending damaging news by telegraph. A few weeks later, the government later gave the Confederate postal service authority to censor the mail.

The war departments of both the Union and Confederacy also gave officers in the field wide latitude in dealing with correspondents as they saw fit. Commanders took matters into their own hands by barring reporters from their camps and taking various forms of disciplinary action against journalists. Officers believed the actions were necessary to deter reporters from publishing information valuable to the other side. But reporters complained that commanders acted arbitrarily and that too often newsmen did not know the rules they were expected to operate under. Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman even went so far as to try to have a reporter court martialed. A military panel found the correspondent not guilty, but he was ordered outside the army’s lines.

Newsmen on both sides recognized that irresponsible correspondents were writing reckless stories that hurt their side. In a letter to the Savannah Republican, Alexander wrote: “The truth is there are correspondents who invariably magnify our successes and depreciate our losses, and who when there is a dearth of news will draw upon their imaginations for their facts. The war abounds in more romantic incidents and thrilling adventures than poet ever imagined or novelist described; and it would be well if the writers of fiction from the army . . . would remember this fact.” But Alexander also repeatedly argued for the necessity of a free press. “This is the people’s war,” he wrote. “Their sons and brothers make up the army, and their means, and their alone support it. And shall they not be allowed to know anything that is transpiring within that army?”[11]

The other forms of press suppression during the war were the closing of newspapers considered disloyal, the arrest of editors, and the denial of postal privileges. One study found that ninety-two newspapers were subjected to some form of restriction, and one hundred and eleven were wrecked by mobs. The vast majority of the incidents took place in the North. Military commanders or political leaders, concerned about the effect of virulent editorials by the Democratic press, ordered many of the newspaper closings. But others were the result of angry citizens or soldiers acting on their own and usually with force.

The four years of fighting took a devastating toll on the South’s press. No sooner had the fighting started, than newspapers and magazines in the eleven Confederate states experienced shortages of materials and staff that made publishing difficult, and, in numerous cases, impossible. As more and more areas of the Confederacy fell, newspapers in the captured cities and towns were taken over by Federal troops or wrecked. The shortages and closings continued to the point where less than half of the South’s newspapers and magazines still were publishing at the end of the war.

At the same time, the war had a positive impact on journalistic practices in the North and South. Reporting methods and writing styles employed by the press changed to better cover a war of such complexity and scale. The standards for reporting and writing generally rose. The best editors in the North and South set high expectations for their correspondents. They wanted stories to be accurate, complete, and sent in a timely fashion. The best newsmen for the North and South showed considerable enterprise in providing interesting, informative, and insightful stories during the periods when the two armies were not fighting. The stories gave readers revealing pictures of entertainment, camp life, and religious ceremonies, as well as picket duty, crimes, and military punishment.

Newspapers also took advantage of nineteenth-century technological developments to get news of the fighting into the hands of more readers and to do so more quickly. The telegraph was used extensively to reporting breaking news. And high-speed presses allowed newspapers to print more copies and faster than they had ever done before. The demand for news prompted some news to begin publishing both morning and evening editions for the first time. Some publishers also initiated a Sunday edition for the first time. Most all dailies stepped up their use of “extras.”

More than they had ever done before, citizens of the Union and the Confederacy turned to the press for news. With Americans fighting against Americans, the war was the biggest event in people’s lives, and they could not get enough information about what was taking place. The war helped make the United States a nation of newspaper and magazine readers. The interest in news was probably best expressed by Oliver Wendell Holmes. Toward the end of the war, Holmes remarked that, “We must have something to eat, and the papers to read. Everything else we can give up.”[12]

- [1] Savannah Republican, October 1, 1862.

- [2] Jos. C.D. Kennedy, Preliminary Report on the Eighth Census, 1860 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office), 101-102.

- [3] Charleston Courier, May 20, 1862.

- [4] Quoted in J. Cutler Andrews, The North Reports the Civil War (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1955), 429-430.

- [5] Charleston Courier, September 11, 1862.

- [6] The Press Association of the Confederate States of America (Griffin, GA: Hill & Swayze’s Printing House, 1863), 29, 41.

- [7][7][7] Quoted in Judith Bookbinder and Sheila Gallagher, First Hand: Civil War Drawings from the Becker Collection (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 47.

- [8] New York Times, June 9, 1863.

- [9] Quoted in Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951), 195.

- [10] Quoted in Carl R. Osthaus, Partisans of the Southern Press: Editorial Spokesmen of the Nineteenth Century (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press,, 1994 ) 101-117.

- [11] Savannah Republican, June 16, 1862.

- [12] Atlantic Monthly, September 8, 1861.

If you can read only one book:

Risley, Ford. Civil War Journalism. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio/Praeger, 2012.

Books:

Bulla, David W. & Gregory Borchard. Journalism in the Civil War Era. New York: Peter Lang, 2010.

Andrews, J. Cutler. The North Reports the Civil War. Pittsburg, PA: University of Pittsburg Press, 1955.

———. The South Reports the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Copeland, David A., ed. The Greenwood Library of American War Reporting: The Civil War, North and South. 8 vols. Westport, Connecticut/London, UK: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Harper, Robert S. Lincoln and the Press. New York: McGraw Hill, 1951.

Marszalek, John F. Sherman’s Other War: The General and the Civil War Press. Memphis, TN: Memphis State University Press, 1981.

McNeely, Patricia G., Debra Reddin van Tuyll & Henry H. Schulte. Knights of the Quill: Confederate Correspondents and their Civil War Reporting. West Lafayette. IN: Purdue University Press, 2010.

Neely, Mark A. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Ray, Frederick E. “Our Special Artist”: Alfred R. Waud’s Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 1994.

Sachsman, David B., S. Kittrell Rushing, & Roy Morris Jr., eds. Words at War: The Civil War and American Journalism. Ashland, OH: Purdue University Press, 2008.

Smith, Reed W. Samuel Medary and the Crisis: Testing the Limits of Press Freedom. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1995.

Thompson, Jr., W. Fletcher. The Image of War: The Pictorial Reporting of the American Civil War. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1960.

Zeller, Bob. The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2005.

Organizations:

American Journalism Historians Association

The AJHA is a scholarly organization devoted to the study of mass media history.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.