Civil War Military Organization

by Garry E. Adelman

The sheer scale of the Civil War led on both sides to the creation of a far more elaborate and efficiently organized military than had been necessary before.

The contending armies in the Civil War were organized with the intent of establishing smooth command and control in camp and on the battlefield. When the war began, neither side knew exactly which army structure would be most effective. Both sides explored a variety of structures throughout the war in response to new currents in strategic thought and the demands of specific circumstances. The Civil War codified several elements of army structure that are still used today.

There were three broad branches of the armed forces on land: infantry, cavalry, and artillery. One of the most significant themes in the evolution of Civil War armies was the gradual division of the three branches. At the outset of hostilities, it was not uncommon to see a brigade that consisted of infantry regiments and cavalry regiments. Over time, leaders on both sides realized that this jumble of responsibilities led to problems on the battlefield.

On the Union side units comprised of “regular” soldiers—those established in the armed forces before the Civil War and which bore a “U.S.” designation—or “volunteer” soldiers—those which consisted of men serving in state-based units that were typically created specifically for the Civil War. Confederate soldiers could also join national “C.S.” units, but most were in state-based units.[1]

Infantry

The majority of servicemen during the Civil War joined the infantry. Infantrymen were foot soldiers who wielded muskets and whose officers carried swords and pistols. Upon enlistment, infantrymen typically joined companies, usually comprised of men from the same town or county or part of a state. On paper, companies were supposed to contain 100 men. In practice, due primarily to enlistment issues, illness, casualties, and desertion, they often consisted of closer to 30-50 men. Within each company, the soldiers were further divided into platoons and squads. Each company was usually under the command of a captain, who was assisted by a first lieutenant and a second lieutenant.[2] At first, companies had text-based names like the Columbus Rifles or the Mifflin Guards, for example, but after they were further organized they would be assigned a company alphabetic letter, such as “Company G.”

Company G, 93rd New York Infantry. Generally, infantrymen on both sides would be denoted with blue stripes or piping on the soldiers’ hats, coats and pants. (Library of Congress)

Companies were grouped together to form regiments—the fighting unit with which soldiers most identified. The regiment was the basic maneuver unit of the Civil War. Regiments could consist of just a few companies or as many as fourteen, but ten was the official number—ten companies of 100 men meant that regiments, on paper, were composed of 1,000 officers and men. Yet because of undersized companies, especially as the war progressed the average Civil War regiment at mid-war consisted of 300-500 soldiers. Volunteer regiments were denoted by numbers followed by the state they represented, for example, the 99th Pennsylvania or the 7th South Carolina. Regiments were ideally commanded by colonels (the “commanding officer”) who oversaw two field officers—the lieutenant colonel and the major—and 30 “line” officers: ten captains and twenty lieutenants, who were in charge of the companies. A few more officers might work on the colonel’s staff as adjutants and aides. Noncommissioned officers—sergeant majors, sergeants and corporals—were also responsible for company-level duties.

Regiments were grouped together to form brigades. Brigades consisted of anywhere from two to seven regiments for a fighting strength that could range from a few hundred to 2,000-4,000 soldiers. A brigadier general ideally commanded a brigade, but colonels and sometimes even lieutenant colonels regularly led brigades. When time and will allowed, brigades engaged in training as a unit—“brigade drill.”

Up to the brigade level, the Union and Confederate armies were organized in the same fashion and were of similar size. The Confederate army was much more likely to “brigade” regiments from a particular state together than its Union counterpart. Famous brigades emerged on both sides such as the “Stonewall Brigade” and the “Iron Brigade.”

Brigades were grouped into divisions, the size of which varied between Union and Confederate armies. The Confederacy’s divisions tended to be larger, with four or five brigades per division, while the Union most often had to only have two or three brigades per division. Both sides stipulated that a major general command a division, but Union divisions were sometimes commanded by brigadier generals and occasionally even by colonels. The Confederacy, however, rarely employed anyone below the rank of major general at the helm of a division.

Two or more divisions formed a corps, and here the ranking on the opposing sides diverges. Throughout most of the Civil War, United States general officers could only hope to attain the rank of major general. The sole rank above it, lieutenant general, was only bestowed during the war to Ulysses S. Grant in 1864. At the outset, however, Confederate general officers had more room for rank elevation. There were numerous slots available for lieutenant generals and a small number for the rank of “full” general—simply called “general.”[3]

A Confederate corps was ideally commanded by a lieutenant general, though they were sometimes commanded by major generals. A Union corps was ideally commanded by a major general, although brigadier generals sometimes took the command of a corps.

The armies of the Civil War varied greatly in size from two small corps of just a few thousand soldiers to behemoths of several corps of more than 100,000 officers and men. Union armies were commanded by major generals while Confederate armies were under the command of a full general or lieutenant general. At the corps and army level, leadership would be determined by seniority among the available major generals, or by intervention from Presidents Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis.

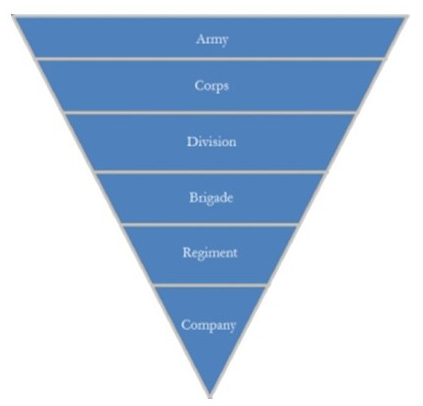

A typical late-war infantry structure (Civil War Trust)

When a division or corps commander was killed or wounded in battle there would be a grand shuffling of responsibility as every man beneath him took one step up in the chain of command. When an officer went down, his replacement was supposed to come from the most senior of his subordinates—a brigadier general replaced by the senior colonel in his brigade, the colonel replaced by the major, and so on. Of course, a colonel lost in a cloud of gun smoke one mile away from his brigade commander would not immediately know of his de facto promotion. Only in unusual circumstances would an officer's fall lead to a somewhat smooth transition of authority—it was far more common for the chain to break down and for the questions of seniority to be worked out afterwards. One division's assault at Fredericksburg collapsed after two of its brigade commanders got trapped under falling horses and could not be immediately found.

It is commonly assumed that there was only one army per nation, but in fact both nations had multiple armies in the field. The most well-known Confederate armies are the Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee for most of the war, and the Army of Tennessee, which had a string of different commanders. The Union Army of the Potomac was Lee's primary opponent, while the Army of the Cumberland and Army of the Tennessee operated further to the west, among others.

Cavalry

Cavalrymen operated primarily on horseback to reconnoiter, scout, and screen on behalf of the army they supported. Cavalry forces also served to delay enemy advances and attack enemy soldiers. Cavalrymen were armed most often with carbines (shorter long-arms that were easier to load and fire on horseback), pistols, and sabers.

Both sides (the Union to a much greater extent than the Confederacy) struggled at the war’s outset to find the most effective way to organize and employ their cavalry forces. Cavalry units were often scattered in small groups throughout an army and performing limited functions. By the middle of the war, however, the cavalry arm was organized on both sides (and commanded by officers of rank), in much the same way as the infantry described above. Both sides formed cavalry brigades consisting of multiple regiments which generally consisted of four to ten companies. Like the infantry, most companies and regiments were understrength throughout the war. Sometimes a few companies on both sides would be grouped into “battalions.”

From 1863 onward, the Union organized its brigades into divisions and thence into cavalry corps whereas Confederate cavalry were most often grouped no higher than division level.

Photos of mounted cavalry units are rather rare since horses often moved during the exposure. Cavalrymen on both sides were generally distinguishable by yellow stripes on their uniforms. (Library of Congress)

Artillery

Servicemen in the artillery branch moved and operated cannons in support of infantry and cavalry objectives. The smallest unit of organization for the artillery was called a “piece,” which was one cannon. Each piece was serviced by 8-20 men, some actually operating the cannon and others providing logistical support such as driving battery wagons and filling limber chests. The pieces were then organized into a section, which consisted of two cannons, ideally commanded by a lieutenant.

Two or more sections formed a battery, commanded by a captain who oversaw the lieutenants (commanding sections) below him. In the South, batteries tended to contain two sections and in the North they tended to contain three sections. Batteries tended to consist of 100 to 150 officers and men. [4]

Like the cavalry arm, both sides struggled in the early parts of the war to find the most effective means of organizing the artillery. Batteries were sometimes attached to regiments, scattered throughout the army thereby precluding the easy massing of artillery when needed. By mid-war, however, armies north and south recognized the need to have groups of batteries under the command of a single officer and also to have a large reserve of guns that could be employed to the greatest benefit.

Both sides organized their batteries into groups of two or more batteries called brigades by the Union and battalions by the Confederates. These units would be ideally commanded by colonels or lieutenant colonels but majors, captains and even lieutenants could sometimes be found at their helms.

Despite having their own organization, brigades and battalions were often connected to an infantry regiment or brigade with the commanding officer of that infantry unit having authority over the artillery commanding officer. The batteries or battalions grouped as “reserve” artillery, reported directly to their army’s chief of artillery, usually a brigadier general.

Artillerymen, who if seen in color would be wearing red stripes, pose around a smoothbore cannon and limber. (Library of Congress)

General Headquarters

In command of each army was a general whose headquarters was run by an assemblage of staff officers. These positions dealt with every aspect of the army. Positions included chief of staff, inspector general, medical director, chief of ordnance, military secretary, chief of commissary, chief quartermaster, chief of artillery, and others. Under each of these commanders began a new chain of command.

Conclusion

The organization of the armies was the foundation of military strategy during the Civil War. Within these organizational units, orders were carried out and movements were made across the battlefield. Although there were some differences in the organizational structure of the Union and Confederate armies, the sheer scale of the Civil War led on both sides to the creation of a far more elaborate and efficiently organized military than had been necessary before.

- [1] Margaret Wagner, Gary Gallagher & Paul Finkelman, eds. The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2009), 377-88.

- [2] Mark Mayo Boatner, II, ed., The Civil War Dictionary. (New York: Random House, 1959), 610.

- [3] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964).

- [4] Dean S. Thomas, Cannons: An Introduction to Civil War Artillery (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1986), 3-10.

If you can read only one book:

Mark M. Boatner III, Mark Mayo, Allen C. Northrop & Lowell I Miller. The Civil War Dictionary (New York: David McKay, 1959), 610-13, 119-21, 328-9, 25-26.

Books:

Griffith, Paddy. Battle Tactics of the American Civil War (Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2001).

Hardee, William J. Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics (Memphis, TN: Hutton & Freligh, 1861).

Nosworthy, Brent. The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War (New York: Caroll & Graf, 2003).

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959).

———. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965).

Wilson, Jerre W. The American Civil War: The Evolution of Field Artillery, Organization, and Employment (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, 1993).

Organizations:

The Civil War Trust

A non-profit organization, the Civil War Trust dedicated to preserving America’s endangered Civil War battlefields. The Trust also promotes educational programs to inform the public of the war’s history.

Web Resources:

Civil War In4: Army Organization. This is the Civil War Trust video describing the organization of the armies In4 Minutes.

Civil War In4: Artillery. This is the Civil War Trust video describing Civil War artillery In4 Minutes.

Civil War Army Organization. This is a paper of the Civil War Trust describing Civil War Army Organization.

Civil War In4: Armies. This is the Civil War Trust video describing Civil War armies In4 Minutes.

To the Sound of the Guns. This is Craig Swain’s blog focused on Civil War battlefields, artillery, markers and monuments.

Rantings of a Civil War Historian. This is Eric Wittenberg’s blog about the Civil War focusing on cavalry in particular.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.