Civil War Pensions

by Kathleen L. Gorman

History of the Union federal and Confederate state pensions systems

For most modern Americans the image of Civil War veterans is the one they have seen in the movies or read in novels. The old man, still in the remnants of his uniform, recounts stories of wartime bravery for an adoring crowd. It does not matter for the image if the veteran was a Confederate or Union veteran. The reality of the situation was, as usual, quite different than the image. By the 1890s (when the Civil War commemoration movement was at its height) most veterans were in their 50s and 60s, feeling the effects of both their physical war wounds and the nation’s economic collapse, and desperate for some kind of help from anyone who could supply it. Because most Civil War soldiers were either farmers or laborers, their growing inability to do physical labor meant that pensions (or other governmental economic assistance) would be their only source of support.

Today we are comfortable with providing both tangible and intangible benefits to our veterans. There is widespread agreement that having put their own lives on hold to serve their country, they should be rewarded for that service. The Civil War provided significant challenges in that more than two million veterans could legitimately claim the attention of their government. An unknown number (but probably a pretty large percentage) were physically or emotionally damaged by what they had been through. Their hometowns threw them parades, their family was (usually) thrilled to have them back, but it was just not enough. What many of them needed was tangible economic assistance and the nation already had a history of providing that in the form of pensions. But pension systems after the Civil War were more complicated, more divisive, and more expensive than they had ever been and they also provided a model for future conflicts that would remain in place until after World War 2.

There was not just one pension system put in place after the war. Union soldiers were covered under the federal system while each former Confederate state had to create and fund its own pension system. And in a change from previous conflicts, it was not only white male veterans who were covered. African American veterans on the Union side were eligible for pensions from the very beginning. Women were also included both as widows and as veterans (primarily nurses) as time went on. Orphaned children were also eligible for assistance although the process was daunting. Each category had its own set of eligibility rules and benefit limits that changed dramatically over time and affected politics on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line.

For Union soldiers, the pension system began in 1862. Soldiers who were disabled as a result of their service were eligible for pensions; the amount depended on their rank and their injury. Dependents (widows and children) of soldiers who were killed on duty were also eligible. No one got rich from these early pensions. A “totally disabled” private received just $8/month from the first pension system. But amounts increased as it became necessary to recruit soldiers to a war that was no longer popular or easy, and pensions served as recruiting tools.

These first recipients only received benefits from the time of their application. That rule changed in 1879 with the passage of the Arrears Act. The Arrears Act provided veterans a lump sum payment to cover the time between when they left the military and when they applied for the pension. It resulted in both an increase in the number of pensioners and in the amount being expended on pensions. However, the veteran still had to have been disabled as a result of his time in the service. As time moved on the veterans and their families needed more and more assistance, even if they had survived the war relatively intact.

The biggest single change to the pension system came in 1890 with the Dependent Pension Act. Because most veterans did some kind of manual labor to support themselves and their families, and their ability to do so declined over time, political pressure for more help increased (as did the public pleading and private, desperate letters). The 1890 Act expanded eligibility to veterans who were disabled and unable to do manual labor even if that disability was not a direct result of the war. They just had to have served ninety days and been honorably discharged. The result was a huge increase in expenditures and numbers of veterans receiving a pension. More than a million men were on the pension rolls by 1893 and pensions ate more than 40% of the federal government’s revenue. One of the side effects of this legislation was a large number of men transferring their pensions from their previous disability pensions to these new service pensions because the new pensions paid more.

The last major change to the pension laws came in 1907 when old age itself was considered a disability. The amount of the pension depended solely on the age of the applicant. By 1910 more than 90% of living Union veterans were receiving some kind of government assistance. The last Union pensioner was Albert Woolson who died in 1956, but that was not the end of Civil War pensions. The last known widow died in 2008 and there were still at least two dependents receiving benefits in 2012.

For widows, eligibility rules focused on date of marriage and if they had remarried. Early pensions required that the service member must have died in service, the widow had to have been married to him at the time of his death, and she could not have remarried. As the rules for veterans changed, so did the rules for widows. The 1890 act allowed widows to receive pensions if their husbands were disabled for any reason at the time of their death, not just due to injuries received in service. In 1901 a widow became eligible for a pension even if she had remarried, so long as she was again a widow. Congress was still averse to allowing a widow to receive money if she was still remarried. The rules on remarriage were also eased over time until the government no longer stopped any widow of an honorably discharged veteran from receiving aid in 1916. Rules on dependents receiving pensions echoed those of widows with the 1890 law allowing completely physically or mentally disabled dependents to receive pensions throughout their life.

Widows were not the only women to receive pensions. Union nurses began receiving them at the rate of $12 a month in 1892. Their requirements were at least six months of service, an honorable discharge, and an inability to support themselves. The push to get nurses pensions was spearheaded by Annie Wittenmyer, former army nurse and continual activist after the war.

The Civil War pension system was color blind in that there was nothing in the application process that required applicants to be white. But recent scholarly works have made it clear that the process itself was far from color blind. Because African American soldiers were both less likely initially to be assigned to combat roles, and then less likely to be hospitalized (early disability applications required documentation from hospitals) if injured, they could not produce the documentation required by the application process. And they were less likely than their white counterparts to have the money necessary to complete the process. Ultimately the fate of black veterans’ applications was decided by white bureaucrats who found it easy to turn them down without fear of retribution. An interesting side note is that the Grand Army of the Republic actively campaigned for their black brethren to be granted pensions just as white veterans were.

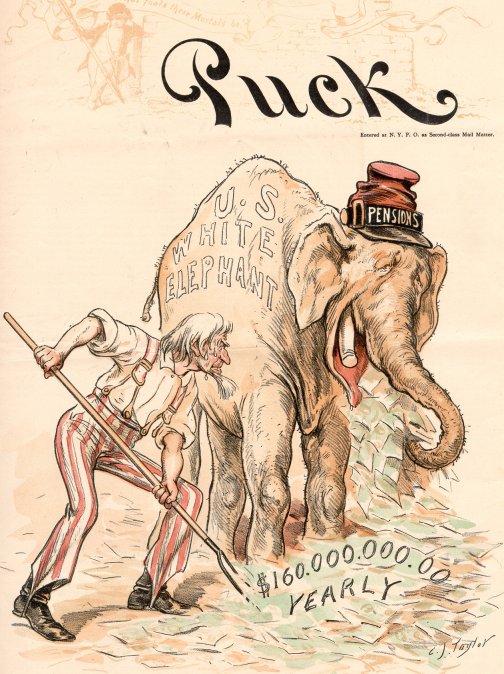

The federal pension system profoundly affected both the American political and economic systems in the decades after the war. President Grover Cleveland vetoed more than 200 bills related to pensions (most were private bills for veterans who did not qualify under the regular rules) and paid for it with his loss in the 1888 presidential election. However, his successor Benjamin Harrison was equally quick to sign pension bills regardless of the validity of the claim and Cleveland was able to defeat him in their 1892 rematch citing corruption in the process. Both major political parties catered to the popular Grand Army of the Republic and portrayed themselves as the veterans’ friends. The pension system created a whole new profession, pension lawyers who worked the system to their own advantage and became the stars of many political cartoons.

The actual application process required the veteran to fill out a detailed form about his service, disability, and current status. The applicant was also required to supply witnesses to all of the above and then to submit to a physical examination by approved physicians if the pension was related to a disability. All of this work required time, travel, and money that many veterans did not have to spare. Pension attorneys could help with the process in exchange for future financial reward. So it was not only the veterans who had a stake in the continual increase in amount of pensions but also a whole new and powerful cottage industry.

Pension payments grew gradually over time starting with that $8/month for a completely disabled private in 1862. A law passed in 1912 increased the rate to a maximum of $30 a month for both Civil War and Mexican War veterans. Funding such a massive pension system was not an easy thing. The federal government found it most economically and politically expedient to rely on adjusting the tariff rate as necessary to pay for it all. The McKinley Tariff of 1890 pushed the tariff rate to as high as 49% on some imported goods and earned the enmity of non-veteran groups, particularly business organizations. From the end of the Civil War until the beginning of World War 1, the treatment of Civil War veterans was constantly played out publically and used by both major political parties. And this was true in both North and South.

Confederate veterans faced an entirely different set of problems than their northern counterparts. They were returning home to a region that had lost the war and had been completely changed by it. They were not eligible for assistance from the federal government and their home states were a mess in every possible way. And they were heroes despite it all. It was that image of Confederate soldiers as heroes that made it almost mandatory for each of their home states to provide for them. The eligibility requirements for each Southern state were slightly different but close enough that Georgia provides a model for all of them.

Artificial limbs were the first form of tangible assistance provided to Southern veterans. Georgia began providing free (if you ignore the cost of travel and work time lost) artificial limbs in 1871. It is hard to imagine what those veterans had been doing to get by in the years since they had been injured and it is hard to imagine them making the trip to the state capital to get their new limbs.

Most Southern pension systems followed the basic federal model although they started much later. Assistance was provided first to those disabled during the war at rates based on their level of disability. It was in 1889 that Georgia began providing annual pension payments to “disabled and diseased” veterans with the amounts varying depending on disability. Widows became eligible in 1893. Three years later pension payments began to those unable to economically care for themselves, again following the federal model. It was not until 1920 that income restrictions were removed. Widows saw continuing changes in their eligibility rules until in 1944 they could get pensions ($30 a month) even if they had remarried.

Because southern states could not use tariffs to fund their pensions, they needed alternative revenue sources. Georgia turned to tobacco taxes to do so but found that those revenues were not even enough during the Great Depression. Part of the issue was that state officials continually underestimated the numbers of eligible pensioners and how much those numbers would change annually. It is easy to see why they had such trouble. In 1937 Georgia had 232 veterans receiving pensions but still 1377 widows, all of whom were eligible for $30 a month even in the depths of the Depression. The state did miss a few payments when revenue did not match expenditures, prompting an avalanche of letters to the state’s pension commissioner begging for help. In 1931 Commissioner J. Hunt received this plea from Mrs. R.C. Dubberly: “My mother is blind and almost helpless and it does seem like when these old people get like that they ought to get a little extra instead of cutting them out of a months pay.”

There was not much political debate in the old Confederacy about providing pensions to their heroes. Opposing them was like opposing everything the South still stood for. And with the mythology of the Lost Cause at its height, that would be political suicide. The Confederate pension system even more so than the Union side relied on patronage. Confederate veterans had to produce comrades who would swear to their “honorable” service. If the veteran did not subscribe to the ideals of the Lost Cause, finding such comrades could be difficult. And the system lasted long after the myth was prevalent. John Salling, possibly the last Confederate veteran (there is some dispute) died in 1958 while the last known Confederate widow, Maudie Hopkins, died in 2008. There may be one or two others still living who do not wish to be identified. If the numbers seem not to be that important, in the state of Georgia alone in 1952 there were still 401 widows receiving aid at a cost of $361,000.

The Civil War pension system provided a model for later systems. Its sheer size and complexity warned the federal government of what might happen if there were even bigger wars later. And it also provided desperately needed assistance to thousands who had nowhere else to turn.

If you can read only one book:

Skocpol, Theda, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press, 1992.

Books:

Glasson, William Henry, Federal Military Pensions in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1918.

Glasson, William Henry, History of Military Pension Legislation in the United States. New York: Columbia University Press, 1900.

Gorman, Kathleen, “Confederate Pensions as Southern Social Welfare,” in Elna C. Greene, Before the New Deal: Social Welfare in the South, 1830-1930. Athens GA: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Logue, Larry M. and Blanck, Peter, Race, Ethnicity, and the Treatment of Disability in Post-Civil War America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Shaffer, Donald, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Organizations:

807 S. Woodlawn Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Tel: (773) 702-7709. 5807 S. Woodlawn Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Tel: (773) 702-7709

Web Resources:

Social Security On Line provides an historical background to the development of social security in the United States, including the Civil War period.

National Archives pension files include information submitted by individuals in support of union veterans, widows and dependents claims for pensions.

The USGenWeb Archives Pension Project is an endeavor to provide actual transcriptions of Pension related materials for all Wars prior to 1900.

Georgia Archives contains applications, supporting documentation, and correspondence for indigent or maimed Confederate veterans or indigent widows of Confederate soldiers. Similar archival data is available for other former Confederate States.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.