Class Conflict in the Union and the Confederacy

by Matthew D. Hintz

The Civil War was a conflict that pitted an industrializing, free labor North against a rural, slaveholding South. But there were also internal tensions and strife emerging out of conflict related to class and status within each society. Non-slaveholding whites in the South, Irish-Catholics in the North, women, African Americans, the poor, the wealthy, and white Protestant males, all struggled to either dominate their rivals, or find a seat in the arenas of ideas and power in their respective societies. In the decades prior to the war, a social and economic revolution unfolded primarily in the Northeast and Old Northwest shifting the economic foundation in the North from small craft and subsistence ventures to high level banking, finance, communication, and industrial enterprises. These changes led to class conflict between the working class and elites, between immigrants and natives and between whites and free African Americans. Anglo Protestant elites were suspicious of Irish Catholic and German immigrants and labor unions representing the working class. The suspicion was returned with both anger and resentment. Non-elite whites feared competition from free and emancipated African Americans who in turn feared violence from these working-class whites. During the war these class conflicts resulted in riots and urban unrest, the most famous of these being the New York City Draft Riots in 1863. The ability of elites to pay substitutes to avoid the draft was particularly resented. Irish Catholic and German working men and women looted Protestant Republican businesses, fought nativist gangs and lynched African Americans. Riots were quelled by newly formed police forces and by the use of Union soldiers. While the myth of the Lost Cause presented the South as a united region with a clear sense of purpose in fact the Confederacy was also riven with class conflict. There elite planters and slave-owners led the move to secession. Plantation owners grew cash crops to enhance their wealth rather than converting to needed farming for food. While yeomen farmers grew most of the food in the Confederacy, food became increasingly scarce as the war progressed and outside sources were cut off or food growing regions over run by Union armies. Food riots occurred in the south, most notably the Richmond Food Riot in 1863. Confederate draft legislation which exempted men owning 20 or more slaves, exemption for government employees and the purchasing of substitutes added to class resentment and anger. Another source of conflict was the existence throughout the Confederacy of individual and regional loyalty to the Union. The most obvious manifestation of this was the secession of twenty-seven counties in western Virginia to form West Virginia, loyal to the Union. But throughout the south there were bands of anti-Confederate partisans in harassing, attacking, and undermining Confederate authority through angry mobs, theft, aiding escaped slaves, guerilla warfare or aiding the Union army. And of course, the white classes resented and feared uprisings by African Americans who in turn feared for their lives and safety. The Civil War was not just two sides fighting for different causes. In the North growing divisions between the working class and elites set the stage for the strife arising from the labor movement of the late 19th century. In the Confederacy, the mutual antipathy between the planter elites and the yeoman farmers and the existence of many pockets of loyalty to the Union led to constant action undermining the Confederate cause. Thus, both sides had their own internal class conflicts which undermined their ability to fight their main opponent. Ironically, although the internal conflicts in the Confederacy were much more severe than in the Union, the myth of the Lost Cause obscured this until only very recently when modern historians began investigating these class conflicts more deeply.

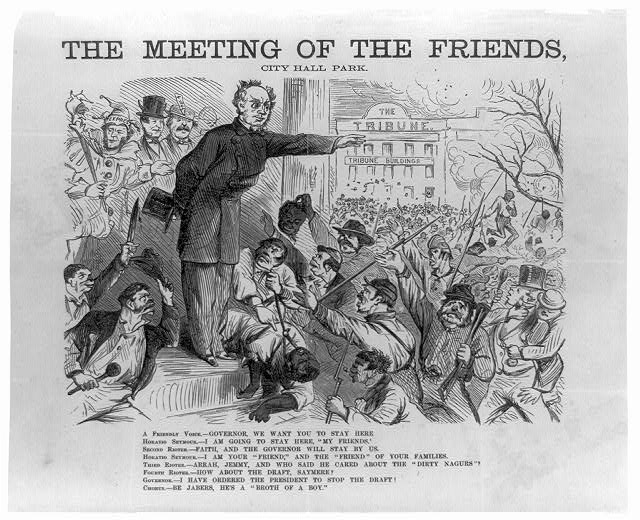

New York Governor Horatio Seymour’s famous “My Friends” speech delivered from the steps of the New York City Hall during the draft riots in 1863. The Cartoon was probably drawn by Henry L. Stephens in 1863 in connection with the New York Tribune.

Picture Courtesy of: The Library of Congress location number cph.3b42499.

To the casual student of history, the Civil War was a showdown between two different economic systems; one of free, or wage, labor, the other of semi-feudalistic chattel slavery. For others, the conflict can be reduced even further: North against South, freedom versus slavery, or simply blue against gray. This is not unsurprising given our preponderance for thinking in binaries and our desire to see complicated relationships rendered with distinct lines of division. The truth, however, is always more complicated and the devil is in the details. The Civil War was a conflict that pitted an industrializing, free labor North against a rural, slaveholding South, but greater scrutiny reveals internal tensions and strife emerging out of conflict related to class and status within each society. Non-slaveholding whites in the South, Irish-Catholics in the North, women, African Americans, the poor, the wealthy, and white Protestant males, all struggled to either dominate their rivals, or find a seat in the arenas of ideas and power in their respective societies.

Until recently, the fractious nature of the war was seldom found in political and military histories. The official record is less interested in conflict on the margins, instead focusing on aspects direct and immediate, whether they are strategic, oratorical, legal, or economic. These points no doubt deserve consideration, but those indirect and seemingly peripheral areas of contention reveal a murky period in which internal and external struggles were exacerbated by war. Historians such as David Williams consider such multilayers of discontent part of a wider series of civil wars dating back to the founding of the Republic. [1] For Williams and those who find value in the experiences of outsiders and dissenters, the war represented merely a single point when “multiple consciousnesses” broke from the traditional order in a violent way. [2]

Some of those previously mentioned casual students of history might ask why shifting away from tradition, or more accurately, incorporating additional voices is necessary when the outcome of the war was more national in scope. This is a fair question. The simplest and most direct answer is that civil war, more so than any other kind of war, always reveals the darker aspects of the society affected, and by definition, civil war challenges any grand narrative assumption that unity exists on either side. In a nation as diverse as the United States was at that time, asking how such a multiclass, multiethnic, multiracial society did not fracture further is an important question that binds powerful key figures in seats of power with those on the margins

The 19th century, more so than the 20th and 21st centuries, was one in which social structures were highly defined and hierarchical. White, elite Protestant families formed the top of this hierarchy followed by those of middle class dispositions, the master craft and yeoman class, industrial laborers, servants, and slaves in the South or free African Americans in the North. Each of these groups can be subdivided, or contain their own separate divisions. Within families, especially those who were part of the emerging middle-class, a regimented order of dependence permeated, with children dependent on parents, wives dependent on husbands, husband as master—an idea modified in the South to include slaves at the bottom of this structure. Class and classes of people reach beyond the economic into realms of race, gender, age, and ancestral roots.[3]

The North–Elite and Poor, Immigrants and Nativists, Blacks and Whites

In the decades prior to the war, a social and economic revolution unfolded primarily in the Northeast and Old Northwest. This market revolution shifted the economic foundation in the North from small craft and subsistence ventures to high level banking, finance, communication, and industrial enterprises. This development is key. The rise of what would become mass industrialization and industrial capitalism was indelible with the creation of an industrial working class. While initially composed of men and women in rural settings, with Lowell, MA, as a prime example, they soon grew into larger independent towns and cities, such as Rochester, NY. The advent of better communication and advances in transportation grouped growing manufacturing towns into regional networks, as with those in Ohio's Western Reserve (Sandusky, Lorain, Elyria, and Cleveland).

Developing separately, international unrest and strife paved the way for an immigration surge the likes of which had not been seen since the early colonial era. The Irish potato famine (1845-1855), triggered mass starvation, disease, and death on the island, unleashing an Irish diaspora seeking refuge in the United States. Approximately 1.5 million Irish immigrants came to American shores in these ten years, settling in urban neighborhoods, seeking work in the burgeoning new industries connected with manufacturing, such as factory labor, shipping, and sundry other service related employment.[4] Irish immigrants, who were predominantly Catholic, faced persecution by an Anglo-Protestant workforce who feared the power of the Catholic Church, as well as the competition brought by cheap and desperate “outside” labor.

International discord in the form of revolution brought immigrants from other corners across the sea. The 1848 Revolution, which sought the overthrow of feudalistic and monarchical power in several Central and Western European states, most famously in the Germanic states, plunged these regions into their own civil unrest and war as radical republicanism spread across Europe. The failure of the revolutions to bring about desired reforms drove some of these radicals to find safe haven in the United States, especially in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Although the Germans, some of whom were Catholic while others were Protestant, would assimilate into American society, like the Irish they were persecuted for their political beliefs and for their threat to the Anglo-Protestant labor base and control of the market. Thus, like the Irish, German immigrants and German-Americans were marginalized as outsiders.

Historian Bruce Levine notes that German immigrants were distrusted due to their past associations with radical ideas concerning the distribution of power. Referred to as Red Republicans by their critics, German-Americans championed integration, labor reforms, and equitable access to capital through redistribution as the means to create a thoroughly democratic society. Furthermore, German-Americans rejected slavery, likening the system to feudal Europe. This mix placed German-Americans in an unusual position within the broader political divide. While earlier German immigrants gravitated cautiously toward the Democratic Party because of their more welcoming nature and their focus on labor, American born Germans lined up behind the Republican Party because of their strong abolitionist sentiment; this latter fact despite of the air of suspicion Anglo-Saxon Protestant Republicans still cast on their German-American allies.[5]

Lastly, an important ingredient in the class structure of American society is race. Regardless of where one lived in the United States in the 1860s, the lowest position on the social ladder belonged to black Americans. Indeed, while slavery existed in the South, it is important to remember that non-white persons in the North, on the whole, were not citizens of their communities, had little-to-no official standing, and lacked the benefit of the basic rights that living in the United States had to offer. Any and all rights accorded to black Americans were, more or less, courtesies on the part of officials and benefactors. States like Ohio, the first state founded where slavery was not allowed to legally exist, instituted its own black codes that sought to maintain a white majority and prevent miscegenation. Other northern states followed suit, and while these state laws were locally enforced to different degrees, they demonstrate the discomfort northerners had with non-white persons.

In the eyes of whites, native born Protestants, immigrants, and Catholics, black Americans represented a potential threat to their social economic security and advancement. While abolitionists, especially those in utopian and quasi-utopian societies such as Oberlin, Ohio, viewed the emancipation and education of black Americans as a religious and egalitarian quest to bring forth the new millennium, working class whites who relied on manufacturing and trade crafts, looked upon blacks and abolitionists with suspicion, fearing that the movement would increase competition for work while undercutting wages. Workingmen societies, social clubs, and nativist organizations, as well as ethnic clubs, though holding differences among themselves, found a common foe in the threat of black free labor, and, by extension, the social fears related to miscegenation.

The combination of these elements—internal improvements, industrialization, along with immigration and race—left an indelible mark upon the American landscape that would forever alter the concepts of urban and rural, labor and management, and class. Increased population in the growing cities and company towns brought overcrowding and blight, while the horrendous conditions of factory labor contributed to mental and physical stresses and disabilities that further impacted the working classes. These conditions represented the transition from agrarian societies to mass urbanization where conflict would fester under the strain of multiculturalism. On the eve of the Civil War, the North was grappling with an identity different from that of the Early Republic.

With industrialization came several elements of social discord in the eyes of Anglo-Protestant Americans, immigrants and labor unions being among them. Together these two bred strife between the working class and the elite whose business models demanded faster and faster production speeds and lower wages. In cities like Chicago, New York, Boston, and Cleveland, modern police departments were established and financed by elites in order to protect Anglo-Saxon Protestant power and quell unrest among laborers. [6] This was especially true in urban centers with high levels of Irish Catholic and German immigrants, the former viewed as an extension of European popery, and the latter representing intellectual radicalism and unbridled revolution. [7] The Civil War afforded the Anglo Protestant elite the ability and opportunity to use newly established professional police forces to break-up union meetings and strikes and to keep close observation on suspected radical outsiders in the name of patriotism and “national security.” [8]

The disparity between Anglo Protestants and "foreign" elements manifested in political terms as well. The Republican Party, on the eve of the war, was predominantly made up of Anglo-Protestants who were highly suspicious of European influences at home and abroad, particularly those related to Catholicism or social revolution. In the immediate years leading up to, and continuing through the Civil War, violence and vandalism against Catholic churches and businesses by nativist organizations, as well as the distrust of Protestant fraternal societies by Catholics, generally caused immigrants to join the ranks of the Democratic Party, and thusly, made elements within the Republican Party suspicious of labor activism. [9] This was especially true of the Irish. This distrust of outsiders, and concern with their connection to unions and affiliation with the party of the South, allowed Anglo-Saxon Protestants of all classes to question the loyalty of the immigrant working class and their commitment to the Union, including those who volunteered to fight in its defense.

While Irish Americans displayed various political and ideological beliefs related to labor and slavery, as a bloc they tended to maneuver away from the radical abolitionism that would eventually take root in the Republican Party. This is in part due to the connective tissue between Neo-Puritan culture that dominated the abolitionist movement, making the movement anti-Catholic, as well as the internal fears within the Irish community that increased competition for jobs by free blacks migrating North would drive down wages. In contrast, German immigrants were distrusted due to their past associations with radical ideas in the 1848 German Revolution. Ironically, despite their ardent anti-slavery views and filial love of republican virtue, German American interest in labor unions and socialism brought condemnation by elite Anglo Protestants. [10]

In the battlefield, German American and Irish American soldiers and their supporters back in their home neighborhoods and communities showed growing animosity toward Anglo Protestant officers and leaders. During the war years, many German Americans believed Anglo Protestant officers were either withholding supplies, or not doing their best to ensure German American units received necessary equipment. This concern grew when many communities witnessed what they thought were non-German units getting resupplied at a faster rate. [11] Such perceptions, real or imagined, played out in the press and in the minds of German-Americans and encouraged them to solicit private funds to furnish their own troops to remedy what they considered anti-German treatment by the Anglo Protestant officers.

Further inflaming and dividing the working and professional classes were exercises in political power by the federal government. The Legal Tender Bill of 1862, established a national paper currency in place of gold and silver, and was intended to finance the war while keeping costs, in theory, low. Northern workers and businesses would use newly printed money, but private firms could also lend to the federal government in the form of bond investments. The unfortunate side-effect was twofold, as noted by Phillip Paludan; bonds and more secure forms of finance were purchased by the elite who could profit from the interest, while wage workers earned legal tender that was subject to inflation. [12] Although Anglo Protestant bankers, shop owners, and venture capitalists stood to gain, some, including Senator Thaddeus Stevens, noted that the bond and tender system only protected those with power and wealth, while placing the burden of inflation and financial uncertainty on the poor, vulnerable, and industrial working class. [13]

The culmination of these multiple tensions—working class versus elites, nativists versus immigrants, influx of black labor, and a lack of equitable capital and financial stability—fueled urban unrest which necessitated the use of those earlier formed police departments. The trigger for most of these uprisings was the passage of the Enrollment Act of 1863, which established the first official draft in the North. Enrollment and draft riots erupted in major urban centers in the North, spearheaded by mixed mobs of working class men, women, and the mothers and wives of men already serving. Rebellious behavior varied, but often ranged from intimidation of enrollment or police officers, destruction of public property related to the draft, or, on the extreme end of the spectrum, chaos and murder, the likes of which harkened to the darkest side of human nature.

The most famous example of urban unrest was the New York City Draft Riots of 1863, best remembered in popular culture as the historical backdrop in Martin Scorsese's film, Gangs of New York (2002). Historians still debate over which one of these issues was the most fundamental, but most agree that main source of rage was the draft, and the way it was implemented. [14] The draft itself proved unpopular, but it was the policies of substitution and commutation, enabling those with sufficient wealth to either purchase their way out of service for $300 (commutation), or to hire another to be sent as an alternate (substitution), which exacerbated the existing divisions between the poor, often immigrant, working class Democrats, and wealthier, pro-war Protestant Republicans. The former viewed the draft avoidance options as both unattainable for them, as well as predatory in nature, since the poor were the once who could not avoid the draft.

The riots in New York and other cities saw these multiple conflicts play out in a sea of violence. Irish Catholic, and many German workingmen and women looted Protestant Republican businesses, particularly merchants. They targeted wealthy men with intimidation or violence. They also destroyed property, fought nativist bands, and most unsettling, lynched free blacks. Indeed, with the Emancipation Proclamation issued earlier that year, there was a fear among the lower classes that abolition would further undermine the labor movement and drive wages downward, a sentiment that gave Protestant Republicans the idea that these immigrants and working people were disloyal Confederate sympathizers—a belief that would live on in the postwar years. The nature of the riot in New York was such that Union soldiers who had previously been engaged at Gettysburg were sent to quell the insurrection using military force. In its aftermath, around 100 civilians were killed, including a dozen African Americans who were lynched by the angry mobs before military force ended the rioting.[15]

The strife between the wealthy Protestant elite and industrial working class, especially those who were non-Anglo-Saxon Protestant, was never resolved by the end of the Civil War. While there was certainly some unity between these social groups, particularly German Americans who shared some abolitionist and anti-southern sentiment with their native born Republican brothers, and while there were Irish, German, Welsh, and other first and second-generation immigrants who volunteered for the Union, the mutual hostility related to the ultimate direction of the nation never allowed for true cohesion. In the aftermath of the war, increased immigration, especially from Eastern Europe, and violence between corporations and labor unions bred a kind of tribalism. Northern Protestant Republicans and newly enfranchised African American Republicans feared Irish Catholics and other "outsiders", whose loyalties they already considered suspect, would align themselves with southern Democrats to undermine the federal government's reconstruction policies. The Civil War, so far as these issues with immigrants, labor, and elites is concerned, proved to be the beginning of a new struggle for identity in the wake of crisis.

The South – Planters, Yeomen, Slave Owners and Non-slave Owners and the Politics of Exploitation

The myth of the Lost Cause has presented the South in sweeping and romantic terms. Unlike the North, whose image is stuck somewhere between one of abolitionist liberators, and that of marauding and unscrupulous carpetbaggers, the South has been presented as a region with a sense of its own righteousness and purpose. This is the case, particularly in the present where film and literature highlights this quality even as some of those works acknowledge the darker aspects of slavery and decadence among the planter elite. The myth of the Lost Cause, perpetuated by ladies’ organizations, fraternal societies, the media, and soldiers on both sides, filtered through academia and pushed the realities of the war to the margins. The most notable aspect of the myth of the Lost Cause was the claim that slavery was not a cause of secession. However, a second truth that has been largely expunged through white, pro-Confederate mythmaking, was the division among those southerners who supported secession, the war, and the Confederacy, and those who remained neutral or loyal to the Union. Furthermore, the questionable motives of speculators and agents of the wealthy add a dimension of Southern war profiteering to the southern narrative that is often ignored or attributed to northern carpetbaggers in the post-war years.

As laid out in the "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union," as well as those written by many of the states in the Deep South, the issue of slavery was raised in nearly every document and every speech by those in power. Thus, while roughly three-quarters of white southern families did not own slaves themselves, secession, the framework of the new government, and the ultimate goals of the war centered on the interests of the upper twenty-five percent. [16] Despite these advantages in power over the poor and yeoman classes, the planters’ conclusion that they held firm command over their lessers through the natural order was something of an overstatement. Although many poor, non-slaveholding whites fought for the Confederacy, there existed resentment in many of their ranks. Some of this hostility stemmed from a distrust of the gentleman-elite, while others were pro-Union and resisted secession through partisan warfare. As observed by David Williams, Southerners fought a war on two fronts, one against the Union, the second, among themselves. [17]

The South was predominantly agrarian, a common tie among most southern landowners, whether they were plantation owners or small family farmers. Leading up to the war, land was allocated for the production of foodstuffs, but on plantations it was mainly cash crops, particularly cotton, which had replaced tobacco as the king of the southern plantation system. Yeoman farmers, in contrast to their wealthier counterparts, grew food for subsistence and for local markets, yet, despite this, their value in southern society was relatively small since most of the food consumed by southerners was grown in the North, mostly around the Great Lakes and in the Midwest. The war removed access to this crucial trade resulting in food shortages and subsequent inflation. Although this was a problem in the North, the southern elites, committed to extracting profit from the cash crop system, did little to allocate sufficient acreage for food production. Food speculators, much like their land speculating counterparts, drove up the price of food further, extorting the lower classes who were not always in a position to grow their own food, as many of the men were serving in Southern armies.[18]

Food impressment was a major factor in driving tensions between elite and non-elite. The Confederate government, in need of food to supply their armies, ordered that portions of crops and livestock be confiscated—or forcibly taken in exchange for increasingly inflated Confederate currency. All of these pressures led to food riots in major southern cities. The largest and most notable riot was in Richmond, Virginia, in 1863, where women laid siege to the capital city, breaking windows, stealing food from merchants, looting, and making political demonstrations much to the horror of Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. It took the threat of violence to finally cause the crowds to disperse. [19] The bread riots were an example of the inability of the planter class to fulfill its presumed paternal obligations to the women, families, and other dependents of the South.

By far the most contentious source of tension within the whole of the South was rooted in the cause of secession itself: slavery and the slave system. Much of the power, influence, and wealth were concentrated among the gentleman planter class, which accounted less than a quarter of the entire population of the South. And while there were slaveholders who operated reasonably large farms, or settled in urban areas, like Baltimore or Richmond, and used their slaves for craft and clerical work, the most significant slaveholding body that could wield itself as a solid political force was the planter elite. Where the planter elite led, many men of property were compelled to follow. As David Williams notes, the rank and file of state general assemblies which voted for secession, enacted the Confederacy, and crafted its wartime policy, came directly from this smaller, elite class. Although some non-slave-holding classes rallied in support of remaining in the Union—as had representatives of pro-unionist Tishomingo and Jones counties, both in Mississippi—and even accused southern secessionist leaders of purposely derailing plans that would allow for compromise, the Confederate states seceded.[20]

In the early stages of the Confederate government, many whites living in the mountainous regions in North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, South Carolina, among other regions, rebelled, arguing that secession was not a path they wished to take and that its implementation was the result of a radical, self-interested minority. [21] The central Piedmont and western regions of North Carolina were especially known for their pockets of pro-Union resistors, as was Coffee County, Georgia, and most famously, the twenty-seven counties of western Virginia whose delegates met in Wheeling in 1861 to formally secede from the State of Virginia, forming the State of West Virginia. The presence of pro-Union rebels within the South forced southern military forces, such as the home guard, to divert manpower toward suppressing resistance that threatened supply lines and Confederate military forces. Further complicating the matter was the reality that yeomen and non-land-owning whites forged relationships with escaped slaves and freedmen who assisted in undermining the Confederacy through guerrilla warfare, deception, and espionage.

This latter fact, a point left out of the myth of the Lost Cause, reentered the wider world of popular culture with the release of The Free State of Jones (2016), a film that details the mixing of racial and class conflicts between non-elite southerners and the Confederacy in Jones County, Mississippi. Although the depiction of the Jones County rebellion is Hollywoodized for dramatic purposes, and noted by historian Matthew E. Stanley as perhaps offering a better critique of contemporary racial issues than those of the 19th century, the film, he concludes, stands as an important stepping stone toward placing the complicated history of race, class, secession, and loyalty in front of the broader American public.[22]

For the rebels who fought for the Confederacy, the strife between the planter elite and those below them on the social hierarchy was only subtly different. In addition to food impressment bringing pain to their families and profit of the wealthy, the non-elite, non-slaveholding class resented the privilege of their leaders and the risks they themselves were forced to take on their behalf. Before similar measures were taken in the North, the Confederacy enacted the first conscription legislation in 1862, which, like its northern counterpart, proved remarkably unpopular among the poor who could not purchase substitutes or escape its reach. The Confederacy exempted all government officials as well as any slaveholder who owned twenty or more slaves. [23] At the height of its unpopularity, those clear of eye viewed the arrangement of excusing government officials and the wealthy planters, who were often one and the same and who sued for the conflict, as a "Rich man's war and a poor man's fight" as it had placed the burden for prosecuting the war on those who had no direct benefit from the action.[24]

The Twenty-Slave Law, along with the Enrollment Act, infuriated the non-slaveholding, agrarian classes, encouraging many to desert their duties and/or join the ranks of anti-Confederate partisans in harassing, attacking, and undermining Confederate authority through angry mobs, theft, aiding escaped slaves, or aiding the Union army. [25]

Conclusion

The non-elite, for their part, resisted the influence of those in power. Men and women of the working or yeomen class rebelled, whether it was out of anger or desperation. In the North, anger was dominant as the working men in heavy industry physically resisted the intrusions of police officers and detectives interfering with their labor meetings, and resented the inflation in prices and the unfairness of conscription. In the South men and women of the yeoman class protested, and later took part in riots over food prices and suspicions of hoarding, as well as the tyrannical behavior of food speculators and the failure of the planter elite to protect their lessers. The greatest show of resistance in the South came at the hands of soldiers who deserted to protect their families, or to join pro-Union guerillas who condemned the selfish wartime policies of the Confederate government and the protections it extended to the elite class.

Race, ethnicity, and "foreignness" cannot be ignored from this subject. As discussed earlier, ethnicity in the North, and the perceived foreign qualities of the industrial class by Anglo Protestants divided the working classes politically and culturally and allowed elites to keep them from aligning. Nativists of all classes infiltrated the Republican Party and made it a predominantly Anglo Protestant party, whereas the Irish Catholic and Welsh immigrants joined the Democratic Party because of the latter's position on the labor movement, with German Americans supporting both labor and abolition, thus creating a temporary split between generations. These political, ethnic, and religious divisions brought uneasiness, paranoia, and violence as the North struggled to form its new wartime structures. Furthermore, racial divisions between whites and blacks proved complicated in the North due to prejudices, fear of competition, as well as the belief by white immigrants that blacks were agents of wealthy, Protestant abolitionists. Such views, real and perceived, placed black Americans at the bottom of the social and economic ladder. Likewise, the South, though not as ethnically diverse as the North in terms of its European heritage, emphasized white, Anglo Protestant authority through the plantation system with black slaves at the bottom of the class structure. Yet, this rigid society drove poor whites to find common ground with non-whites, thus lending itself to the potential for alliances in the internal partisan resistance to Confederate authority.

The study of class during the war exposes the common misconception that there were just two sides fighting for different causes as simplistic and untrue. In fact, North and South had their own internal wars that undermined their ability to confront their main opponent effectively. In the case of the North, the growing divisions between working class and elites came to a head during the war and set the stage for the contentious labor movement of the late 19th century. For the South, the heavy handedness of the planter class and lack of a cause that bound all southerners together effectively drove many to join the Union army or pro-Union guerillas, desert, or aid slaves in their escape. Ironically, although the internal conflicts in the Confederacy were much more severe than in the Union, the myth of the Lost Cause obscured this until only very recently when modern historians began investigating these class conflicts more deeply.

- [1] David Williams, A People's History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom (New York: The New Press, 2005), 12.

- [2] Ibid., 4.

- [3] Stephanie McCurry, “The Two Faces of Republicanism: Gender and Proslavery Politics in Antebellum South Carolina,” in Journal of American History 78, no. 4 (March 1992), 1249.

- [4] “The Potato Famine and Irish Immigration to America,” in Constitutional Rights Foundation Bill of Rights in Action 26, no. 2 (Winter 2010), 1.

- [5] Bruce Levine, The Spirit of 1848: German Immigrants, Labor Conflict, and the coming of the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 187.

- [6] Sam Mitrani, The Rise of the Chicago Police Department, Class Conflict 1850-1890 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 16.

- [7] Levine, The Spirit of 1848, 5.

- [8] Williams, People's History, 5

- [9] Phillip Shaw Paludan, A People's Contest: The Union & Civil War, 1861-1865 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1988), 175.

- [10] Levine, The Spirit of 1848, 187.

- [11] Ibid., 257.

- [12] Paludan, A People's Contest, 116.

- [13] Ibid., 112.

- [14] Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), 9.

- [15] Williams, People's History, 186.

- [16] Charles C. Bolton, "Planters, Plain Folk, and Poor Whites in the Old South," in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, Lacy K. Ford, ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 75.

- [17] David Williams, Bitterly Divided: The South's Inner Civil War (New York: The New Press, 2008), 1.

- [18] Williams, People's History, 5.

- [19] William Blair, Virginia's Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 73.

- [20] Jeff T. Giambrone in Mississippi’s War: Slavery and Secession, documentary, 2014, Mississippi Public Broadcasting, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3CFD2RRF80 , accessed July 21, 2017.

- [21] David Williams, Rich Man's War: Class, Caste, and Confederate Defeat in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999), 4.

- [22] Matthew E. Stanley, “Review: Free State of Jones, Directed by Gary Ross,” in The Public Historian 39, no. 2 (May 2017): 96

- [23] Williams, Rich Man's War, 129-30.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] Ibid.

If you can read only one book:

Williams, David. A People's History of The Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom. New York: New Press, 2005.

Books:

Bernstein, Iver. The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Fleche, Andre M. The Revolution of 1861: the American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Nelson, Scott Reynolds and Carol Sheriff, eds. A People at War: Civilians and Soldiers in America's Civil War, 1854-1877. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Paludan, Phillip Shaw. A People's Contest: The Union & Civil War, 1861-1865. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1988.

Williams, Blair. Virginia's Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Williams, David. Bitterly Divided: The South's Inner Civil War. New York: New Press, 2008.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This is a teaching aid and essay covering Chapter 10 of David Williams’ A People's History of The Civil War.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.