Confederate Commerce Raiders and Privateers

by Mark A. Weitz

Arguably the Confederacy’s maritime efforts rank among its greatest wartime successes. Starting literally from scratch, the Confederacy immediately mustered a small but effective privateer fleet that not only met with some success, but forced the early resolution of the Confederacy’s status as a legitimate belligerent. Following its privateer successes, the Confederacy’s small but formidable commerce raider fleet dealt a crushing blow to the Union merchant marine. Not only did the Confederacy successfully take or destroy hundreds of Union vessels, but it forced the Union to transfer almost 800,000 tons of shipping to foreign carriers to avoid the attacks of the Confederate surface fleet. As the war progressed, the Confederate success on the high seas drove up the cost of maritime insurance premiums making the carriage of goods for Union merchant ships even more costly. But while Confederate maritime efforts were impressive, they never seriously threatened the Union blockade. As a result, most nations, even Great Britain eventually, recognized that the Confederacy’s status as a belligerent had limitations. Most nations would not allow Confederate commerce raiders to claim prizes in their ports. Coal, the essential fuel of 19th century steamships, was often denied to Confederate vessels in neutral ports. After the war the Union made demand on Great Britain for the damage done to its merchant marine by British built commerce raiders. The original claim in 1869 of 2 billion dollars was ultimately reduced through arbitration to 15.5 million dollars in 1871, and finally paid in 1872. Even after it ceased to exist the Confederate Navy continued to have an effect on international law. The Alabama Claims dispute established the principle of international arbitration. In the ensuing years, a movement to codify public international law gained real momentum. In many ways the arbitration of the Alabama Claims laid the groundwork for international institutions of peace like the Hague Convention and the United Nations.

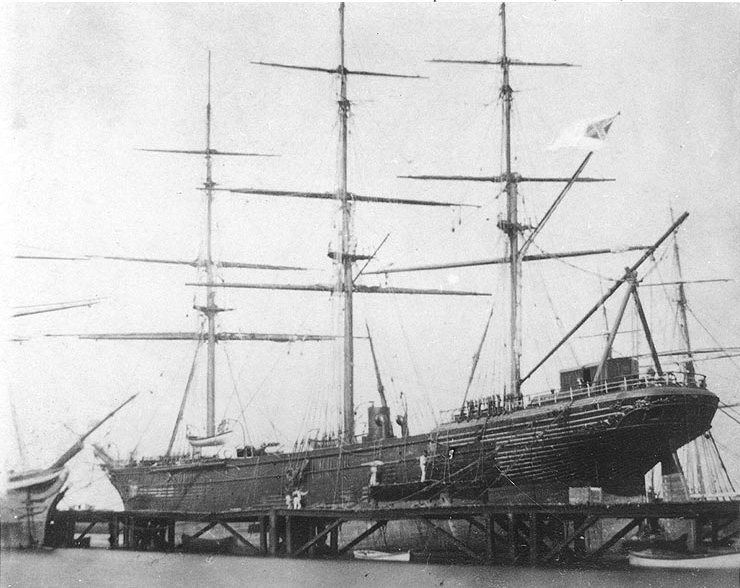

CSS Shenandoah hauled out for repairs at the Williamstown Dockyard, Melbourne, Australia, in February 1865. Note Confederate flag (possibly retouched) flying from her mizzen gaff, and fresh caulking between her planks.

Photograph Courtesy of: The Naval History and Heritage Command, Catalog # NH85964

As the Union military extricated itself from military posts all over the southern United States in the wake of Fort Sumter, the Confederacy had cause to consider what waging war was going to require. The realization began to sink in that regardless of its potential to wage an effective war on land, the Confederacy had no navy to speak of. The Union scuttled or burned any ships it could not take with it, and what remained would be virtually useless. When the war began, Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory could count but thirty-five ships in the Confederate Navy and a navy of some kind would be crucial to the Southern war effort.

It was abundantly clear in the early part of the war that Union strategy included a concerted effort to blockade the Confederacy and breaking the blockade would be important for several reasons. First, if the blockade was ineffective foreign nations could ignore its existence and trade freely with the South. Second, the South remained dependent on outside sources for many of the commodities it did not produce. Since trading with the North was no longer a viable option, Southern dependence on foreign trade increased dramatically. Third, without the ability to break the blockade the Confederacy had little hope of threatening the Union’s merchant marine, thus guaranteeing that the North’s international commerce would go virtually unaffected by the outbreak of hostilities.

The task of running the blockade for trade purposes fell to the scattered and vastly uncoordinated efforts of the Confederacy’s merchant marine, which of all aspects of the war on the oceans proved most easy for the South to recreate. Southern trade had always involved a significant amount of trading vessels. The more demanding role of preying upon Union merchant shipping required more innovation and some foreign help. Not only did the South lack a navy, but it lacked enough shipyards to build one from the ground up. Ultimately the South’s commerce raiders came from two sources: the age-old practice of privateering and the willingness of the British government to clandestinely share the product of its skilled shipbuilders.

Privateers

Privateers struck the first blows early in the war. The practice of authorizing private citizens to wage war on enemy shipping had its genesis in the seventeenth century practice of authorizing private individuals who lost money or property at the hands of a foreign sovereign to recover their losses on the high seas. After proving their claim at home, their government would issue a letter of marque authorizing the injured citizens to prey upon the ships of the offending country as compensation. The practice expanded over time as European nations, locked in costly wars, sought out alternatives to raising navies. During the Seven Years War (1756-1763) Louis XV of France resorted to privateers to supplement his depleted navy and they took over eight hundred British ships. The United States successfully used privateers both in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. But by the mid-nineteenth century the practice fell out of favor and following the Crimean War the major European powers outlawed privateering in the 1856 Declaration of Paris. However, the United States refused to sign the treaty and left the door open for Jefferson Davis and the Confederacy to resurrect the practice in 1861.

On April 17, five days after the firing on Fort Sumter, Jefferson Davis announced the Confederate government would issue letters of marque allowing private citizens to outfit their own ships and prey upon Union shipping. Davis’s announcement brought an avid response. Confederate citizens with the means to equip and man ships applied and received letters of marque to operate on the high seas and on the various rivers within the United States. Although Jefferson Davis insisted that privateer captains strictly abide by the rules of international law and restrict their activities to Union vessels only, he also provided that in addition to paying for prizes, the Confederate government offered to pay twenty percent of the value of any U.S. ship sunk. Profit motives aside, the Confederacy intended to use privateers as a tool of war.

Lincoln saw the danger in a motivated Confederate privateer navy. He reached out to the Europeans and attempted to retroactively adopt the anti-privateering provisions of the Declaration of Paris. Great Britain rejected the all too transparent offer, as did the rest of Europe. But, prior to doing so Lincoln drew a line in the sand at home that threatened to make privateering a very dangerous proposition aside from the possible misfortunes that normally flowed from combat. On April 19, 1861, two days after Davis announced his intention to issue letters of marque, Lincoln served notice that any Confederate privateer captured by the Union would stand trial as a pirate and if convicted would be hanged. Lincoln had in effect denied Confederacy’s legal existence as anything other than a rebellion and therefore it lacked any of the characteristics of state sovereignty that compelled the Union or any other nation to recognize its right to issue letters of marque. Of all the political maneuvering on both sides in the first month of the war, Lincoln’s refusal to recognize the Confederacy’s “right” to issue letters of marque set the stage for a debate that found its way into the United States courts five months later.

To most Southerners who received letters of marque, getting caught by the Union navy seemed a distant possibility as they rushed to capitalize on the opportunity to exercise their patriotism and make a profit at the same time. On June 1, 1861, the Savannah, the first ship to receive Confederate letters of marque, set sail out of Charleston harbor. The brainchild of two members of the Virginia Militia, T. Harrison Baker and John Harleston, the Savannah ran the Union blockade and made for the high seas. Within days it took its first prize, the Joseph, but after sending it on its way back to Charleston with a prize crew aboard, the Savannah discovered firsthand the perils of commerce raiding. The next ship it spotted proved to be a Union man-o-war, the Perry. Days earlier Baker and Harleston had evaded both the Perry and the Minnesota as they made their way through the blockade. Now however the Savannah would have to outfight or outrun the Union warship and it proved incapable of doing either. By nightfall the Savannah had become a war prize. Its captain and crew found themselves headed to New York City and the inhospitable confines of its prison, the Tombs, where they would remain until, true to Lincoln’s word, they stood trial for piracy.

At least the Savannah took a prize. The Petral would not be so fortunate. Sailing out of Charleston Harbor in early August 1861, the privateer never cleared coastal waters. Almost immediately it spotted a sail on the horizon and fired two shots at what the crew believed to be a merchant ship. It was not. The sail belonged to a Union frigate, the U.S.S. St. Lawrence. While the Confederate privateer’s shots fell harmlessly into the sea, the St. Lawrence’s return fire struck the Petral with deadly accuracy, literally cutting the hapless privateer in half. Five members of the crew drowned before the St. Lawrence’s rescue boats could pull them from the ocean. The remainder found themselves bound for New York City to await the same fate as the crew of the Savannah.

The Savannah and the Petral served as examples of the shortcomings of privateering. While both ships had able crews, neither possessed warriors, and the Savannah in particular could have benefitted from men inured to war. In all fairness, the Petral never had a chance. The Savannah could have outrun the Perry, but its crew panicked. Virtually the entire ship’s company ducked with the first salvo from the Union ship and the inability to stay calm destroyed any chance of taking advantage of a small head start that might have been sufficient to allow the Savannah to escape. But as disappointing as the Confederacy’s failures may have been, they paled in comparison to the spectacular success enjoyed by the Confederacy’s privateer fleet, and no ship proved more successful than the Jefferson Davis.

The Jefferson Davis began its life as a slave ship. Seized off the coast of Cuba in 1858 for running slaves under the name the Echo, the ship sold at auction in 1859 and became the property of Captain Robert Hunter of Charleston, South Carolina. Renamed the Putnam, Hunter found a group of investors and petitioned for letters of marque in June 1861. After a refitting that included the addition of five British guns, two 24 pounders and three thirty-two pounders, the privateer, now christened the Jefferson Davis, set sail out of Charleston on June 28, 1861. Among the ninety-man crew was its most valuable asset, its captain, forty-three-year-old Louis M. Coxetter. Although not a military man by training, Union Admiral S.F. DuPont regarded Coxetter as the most skillful captain on the coast. In the seven-week period from its departure until it ran aground off St. Augustine on August 18, 1861, the Jefferson Davis claimed ten prizes and was so successful that what ultimately ended the voyage was the inability to place prize crews aboard captured ships. On August 5, 1861 Coxetter took his last prize and headed for the Florida coast. Off St. Augustine, Florida he captured the Union coal steamer, John Carver, and attempted to bring her to port. However, she drew too much water to bring into the shallow harbor and Coxetter set her ablaze. Then the Jefferson Davis ran aground entering St. Augustine. Coxetter scuttled her and his crew escaped to safety.

A month after the Jefferson Davis set sail the Sumter slipped out of New Orleans and ran the Union blockade. Setting up just outside of Cienfuegos, Cuba it quickly took eight prizes. In total, by mid-July four Confederate privateers had taken twenty-four prizes. The Northern press followed the exploits of this makeshift navy and its successes. Steady reports of Union merchants falling victim to privateers stirred fear among the Union citizenry and created a sense of legitimacy within the international community for the Confederacy’s claim of sovereignty. However, despite the spectacular successes, privateering demonstrated the limits the international community was willing to go in formally recognizing the Confederacy so early in the war. The eight prizes taken by the Sumter had to be forfeited when the Spanish government in Cuba refused to allow the Sumter to claim them as prizes. In addition, failures like the Petral and Savannah reinforced the reality that the Confederacy had no true navy. Thus, aside from the public fears generated by the Jefferson Davis and others, perhaps the greatest impact Confederate privateering had on the war came not on the high seas, but in Northern federal courtrooms where the capture of privateer crews led to piracy trials. At the center of the legal issues lay the true nature of the Confederacy and whether its government could legally issue letters of marque under international law.

The crews of the Savannah and Petral languished in a New York City prison until October 1861. One of the early prizes taken by the Jefferson Davis, the Enchantress, would lead to the third privateer crew to be captured and tried for piracy. Coxetter assigned pilot William Smith and four others to sail the Enchantress back to Charleston. Coxetter had left a black cook, Jacob Garrick, on board the prize to also be sold when he reached South Carolina. With the Enchantress in sight of North Carolina it encountered a Union vessel. All went as planned until Garrick came on deck and began calling out to the Union crew that the ship was being sailed to Charleston as a Confederate prize. The Union warship quickly stopped the Enchantress, boarded her, and sent Smith and his crew to Philadelphia to be tried as pirates.

In October 1861 Smith and his crew went on trial in Philadelphia for piracy. If convicted they faced death. In New York Baker, Harleston, and the crew of the Savannah faced the same fate. The trials literally took place at the same time with Smith’s finishing first. The key legal issue was whether the Confederacy could issue letters of marque. Only sovereign nations could do so under international law. If the Confederacy was not a sovereign nation its letters of marque were worthless. If its letters of marque were invalidated, Smith, Baker, Harelson and every other privateer was nothing but a pirate preying on Union shipping and could be treated as such. The details of the trials are much too voluminous to describe in this piece and are in fact the subject of a full-length monograph. In Philadelphia Smith and his crew were found guilty as charged. In New York, the jury hung on the issue of Confederate sovereignty. Although convicted, Smith and his crew returned to prison while the Union attempted to sort out how to treat one crew as pirates while a northern jury could not decide the same issue for another crew some one hundred miles away.

In the interim Jefferson Davis solved the conundrum, at least in a practical sense. With his sailors facing death sentences Davis made it clear to Lincoln that there was no appreciable difference between Smith and his crew and the two land armies currently doing battle. When a solder was captured on land he was treated as a prisoner of war and exchanged. Davis sent a clear message to Lincoln that if the Union executed Smith and his crew that the Confederacy would treat captured Union soldiers in the same manner. On November 9, 1861 the Confederate War Department instructed General Samuel Winder to select Union prisoners of the same rank and number as the Confederate privateers being held in Philadelphia and New York City. Davis then publicly announced that for every Confederate privateer executed he would have a Union prisoner executed. Faced with the obvious contradiction and not wanting to jeopardize a vastly larger pool of men that would be affected by executing Smith as a pirate, Lincoln relented. The crew of the Petral never stood trial. Although two members of the Savannah died in the Tombs, ultimately the Union released all of the Confederate privateers bringing to a close the Confederacy’s foray into the storied world of privateering.

There was never an “official” end to Confederate privateering, but several factors led to its decline. The inability to bring prizes into neutral ports made the process far more difficult. It became clear by the end of 1861 that even though the Confederacy would be treated as a “belligerent” by the international community, it would not be granted nation status unless it prevailed. To bring a prize to a Confederate port required a crew and success meant the privateer vessel’s crew slowly diminished in order to claim prizes. As the Union blockade became more effective the possibility of profit diminished even more and with it the motive for privateering. By the end of 1861 the Confederacy was also able to muster a small but effective cadre of commerce raiders manned by professional sailors. Some vessels went from being privateers to commissioned Confederate raiders. Ultimately privateering simply gave way to a more concerted and effective conventional strategy to destroy the Union merchant marine.

Commerce Raiders

Unlike the Confederate privateer fleet that had a short, but spectacular run, Confederate commerce raiders posed a lethal threat to Union shipping throughout the war. The C.S.S. Sumter, a vessel associated with the Confederacy’s early privateering efforts, claims the status as the first commissioned Confederate navy war vessel. Leaving New Orleans in June 1861 it preyed on Union shipping until January 1862 when it ran short of coal outside of Gibraltar. It languished there until December of that year when it was sold at auction. Under the command of Raphael Semmes, the Sumter took eighteen ships and demonstrated the potential destructive force that real naval vessels could have on Union commerce. In addition, Semmes cut his teeth so to speak as the Sumter’s commander, and would later use the skills he acquired to make the C.S.S. Alabama the most feared of all Confederate raiders. Over the next three years, commissioned Confederate naval raiders, manned by sailors who were also combatants, ravaged the Union merchant marine.

The Confederacy ultimately put a number of raiders to sea. Conservative estimates show the Confederacy commissioned slightly over twenty wooden and ironclad raiders over the course of the war, but only eight to ten made a difference. Some of its early vessels, like the Nashville, actually lacked any real firepower and often seized Union merchants with wooden Quaker guns. In addition, the Confederacy fought the nuances of international law when it came to refueling with coal in neutral ports and often had to rely on sail power only. But, despite these shortcomings the Confederacy’s commerce riders flourished, in great part because the Union contributed to its own losses. This was an era when commerce ships sailed without naval escorts. If a raider could avoid the blockading Union warships it could prey with impunity on the unarmed Union merchant ships. Union strategy for combating the threat to its merchant fleet left much to be desired. Essentially the Union tried to engage Confederate raiders at or near the last port where they were sighted. The failure proved conspicuous as the US merchant fleet that had been on par with Great Britain’s before the war took decades to recover after the war.

The story of the Confederacy’s Navy is inextricably tied to Great Britain, the nation that produced its two most famous raiders. The C.S.S. Alabama, the most famous of the Confederate raiders is the subject of Donald Rakestraw’s fine piece in this series. For that reason, the details of its birth, exploits, and ultimate demise are left to Professor Rakestraw’s essay. The Alabama took over 60 prizes and its destructive effect on the Union merchant marine gave rise to the Alabama Claims that were not resolved until 1872. But as prolific as the Alabama was, she did not sail alone. A small but effective group of raiders contributed to the devastation of the Union’s merchant marine.

The C.S.S. Florida enjoyed a longer, if more bizarre career, even if it was not as successful as its better-known compatriot. The Florida was the first product of the British ship builders who built ships for the Confederacy. The key to this unique ship building relationship lay in the skills of Captain James Bullock, the Confederacy’s naval agent in Great Britain. Arriving in England on June 4, 1861, Bullock’s task was to oversee and facilitate the building of ships for the Confederate navy. The C.S.S. Florida became the first product of his efforts. The Florida started her career as the Operto. Great Britain represented she had been built for a firm in Palermo, Sicily. In reality, the Confederacy paid for her and the Operto became the Florida as soon as she cleared the British shipyards.

The Florida roamed the Atlantic from March 22, 1862 until October 7, 1864 when the Union, in violation of international law, seized her in the neutral port of Bahia, Brazil. In two and a half years the Florida took thirty-seven prizes under the able leadership of its captain, John Newland Moffitt. However, that number does not accurately reflect the totality of her success. Some of the ships she captured in turn became raiders and added to the destructive force of the Confederacy’s surface fleet. The C.S.S. Tacony and C.S.S. Clarence, both captured by the Florida, added twenty-three more prizes to the Confederacy’s total.

The ability to augment its navy through capture proved important. As the war dragged on and the South’s defeat became more probable, Britain stopped building ships for the Confederacy and began enforcing neutrality laws. In part Britain wanted to avoid the ire of the United States, but its motives went beyond its relationship with the United States. It also saw the potential that other nations might ignore the neutrality laws in some future conflict involving Britain and the desire to avoid any clear precedent on its part motivated a change in position towards the Confederacy. The Confederacy could see the change in attitude as early as 1863. At the insistence of the United States consul to Great Britain, Thomas Dudley, the British seized the Alexandra in April 1863. In 1862 Dudley observed the Alexandra’s construction in the shipyards of W. C. Miller and Son, the same company that had built C.S.S. Florida. Dudley’s steady pressure on local British authorities enmeshed the Alexandra in a legal fight that lasted the rest of the summer of 1863. Ultimately a jury found against the seizure and Britain released the Alexandra. But Dudley’s efforts cast unwanted light on the clandestine British shipbuilding activities and actually stopped the delivery of two vessels commissioned by the Confederacy. The Alexandra sailed to Nassau, but after being detained for an illegal cannon. Local revenue authorities found a twelve-pound cannon and ordinance in the Alexandria’s cargo hold that appeared to be of British design and manufacture. The ship found herself in another legal battle and by the time the Nassau court had ruled in its favor, the war was over.

Perhaps the most successful commerce raider aside from the Alabama and Florida was the C.S.S. Shenandoah. A late addition to the Confederacy’s armada, the raider was originally built by Alexander Stephens & Sons for Robertson & Co. of Glasgow, Scotland, not as a warship, but for East Asia tea trading. Christened the Sea King, she made several runs to the Far East, until October 1864 when the Confederate Navy purchased her from her owners, Wallace Bros. of Liverpool. She escaped England undetected as a trading vessel bound for India and rendezvoused with the Laurel at Funchal, Madeira. The Laurel carried officers, a crew, deck guns, ammunition and everything else needed to convert her to a warship. Under the guidance of Lieutenant James Iredell Waddell, a former U.S. navy officer and her new commander, the C.S.S Shenandoah was commissioned on October 19 1864.

Over the next seven months she preyed upon Union shipping in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, claiming 38 prizes, predominantly Union whalers. In June 1865 Waddell captured the Susan & Abigail and learned for the first time of Robert E. Lee’s surrender over two months before. However, the newspaper article he received also mentioned Jefferson Davis’ pledge to continue to fight on. Waddell then took ten more prizes over the next seven weeks. Finally, on August 3, 1865 Waddell learned of Kirby Smith’s and Joseph Johnston’s surrenders and struck his colors. He refitted as a commercial vessel and unwilling to surrender in a Northern port, he returned to Liverpool where he gave his ship up for good.

The remainder of the Confederate commerce raiding fleet had shorter and less spectacular careers. The CSS Georgia under the command of Captain William Lewis Maury had a brief career in 1863. Converted from a merchant ship, the Japan, she fell victim to the inability to re-coal in neutral ports and spent most of her time on sail-power claiming a small hand-full of prizes until lack of fuel forced her to port in France where she remained for the duration of the war. The CSS Tallahassee and its captain John Taylor Wood, an Annapolis graduate, actually flourished for several months in the summer of 1864 operating in the very shadow of the Union blockade. Restricted by her design that limited her range to under a thousand miles, and further frustrated by the inability to re-coal, the Tallahassee nevertheless claim prizes off New York and Halifax in August 1864. The CSS Chickamauga suffered from the same limitations as the Tallahassee, limited range and re-coaling problems. Captained by John Wilkinson she seized a few prizes in the autumn of 1864.

The CSS Rappahannock had great promise but never had the opportunity to fulfill her potential. She came to the Confederacy in 1863 courtesy of the British. Rappahannock was a retired British warship, the HMS Victor, and the Confederacy purchased and refitted her. But to complete her refitting the Rappahannock made her way across the channel to Calais, France. There she was to pick up some of the guns from the Georgia, whose career was cut short by fuel limitations in France. However, before her refitting could be completed the ship became embroiled in a legal fight as to whether she had properly entered French waters. The dispute kept her from ever getting to sea and she languished in France until July 1865. The CSS Stonewall, the product of Danish shipbuilders, did not take to sea until January 1865. By the time the ship reached American waters the war had ended. She surrendered to Cuban authorities in Havana in May1865 never having fired a shot.

CONCLUSION:

In March 1863 Edward C. Bruce, of Winchester, Virginia penned “The Sea-Kings of the South.” In his concluding stanza he wrote:

“Then flout full high to their parent sky those circled stars of ours,

Where'er the dark-hulled foeman floats, where'er his emblem towers!

Speak for the right, for the truth and light, from the gun's unmuzzled

mouth,

And the fame of the Dane revive again, ye Vikings of the SOUTH!”

In part a tribute to the early success of the C.S.S. Alabama, Bruce’s praise could apply with equal force to the South’s privateers and her other commerce raiders.

Arguably the Confederacy’s maritime efforts rank among its greatest wartime successes. Starting literally from scratch, the Confederacy immediately mustered a small but effective privateer fleet that not only met with some success, but forced the early resolution of the Confederacy’s status as a legitimate belligerent. Following its privateer successes, the Confederacy’s small but formidable commerce raider fleet dealt a crushing blow to the Union merchant marine. Not only did the Confederacy successfully take or destroy hundreds of Union vessels, but it forced the Union to transfer almost 800,000 tons of shipping to foreign carriers to avoid the attacks of the Confederate surface fleet. As the war progressed, the Confederate success on the high seas drove up the cost of maritime insurance premiums making the carriage of goods for Union merchant ships even more costly.

But while Confederate maritime efforts were impressive, they never seriously threatened the Union blockade. As a result, most nations, even Great Britain eventually, recognized that the Confederacy’s status as a belligerent had limitations. Most nations would not allow Confederate commerce raiders to claim prizes in their ports. Coal, the essential fuel of 19th century steamships, was often denied to Confederate vessels in neutral ports. After the war the Union made demand on Great Britain for the damage done to its merchant marine by British built commerce raiders. The original claim in 1869 of 2 billion dollars was ultimately reduced through arbitration to 15.5 million dollars in 1871, and finally paid in 1872.

If you can read only one book:

Symonds, Craig L. The Civil War at Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Books:

Butler, Leslie S. Pirates, Privateers, & Rebel Raiders of the Carolina Coast. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Canney, Donald L. The Confederate Steam Navy: 1861-1865. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History, 2015.

Chaffin, Tom. Sea of Gray: The Around-the- World Odyssey of the Confederate Raider Shenandoah. New York: Hill and Wang. 2006.

Cochran, Hamilton. Blockade Runners of the Confederacy. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1958.

Cook, A. The Alabama Claims. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. 1975.

deKay, James T. The Rebel Raiders: The Warship "Alabama", British Treachery and the American Civil War. London: Pimlico, 2003.

———. The Rebel Raiders: The Astonishing History of the Confederacy's Secret Navy. New York: Ballantine Press, 2003.

Hearn, Chester G. Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union’s High Seas Commerce. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Hughes, Dwight Sturtevant. A Confederate Biography: The Cruise of the CSS Shenandoah. Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2015.

McKenna, Joseph. British Ships in the Confederate Navy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010.

McPherson, James M.War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Marquis, Greg. In Armageddon's Shadow: The Civil War and Canada's Maritime Provinces. Montreal, Kingston, Ithaca and London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.

Scharf, J. Thomas. History of the Confederate States Navy. New York: Random House, 1996.

Weitz, Mark A. The Confederacy on Trial: The Piracy and Sequestration Cases of 1861. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005.

Wilson, Walter E and Gary L. McKay. James D. Bullock: Secret Agent and Mastermind of the Confederate Navy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.