Confederate Veterans' Associations

by James L. Johnson

Confederate veteran groups began forming as early as 1865. The premier Confederate veterans’ organization, the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) was formed June 10, 1889 and dissolved formally May 30, 1951, after the death of its last member. The organization published its magazine, Confederate Veteran from 1893 to 1932. Local camps met one or more times annually. Except for two years the UCV met annually for a National Reunion for the veterans and several times met jointly with the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) the Union veterans’ national organization. After each annual meeting The UCV published their National UCV Programs annually. These were a form of commemorative booklet, a printed description of the annual meetings which functioned as minutes and generally ran to 60-100 or more pages. The UCV was a nonmilitary, educational, social, historical organization concerned with the welfare of its members. Activities included raising funds for and constructing monuments commemorating Confederate heroes and battles, researching and publishing histories, and building Battle Abbey now the home of the Virginia Historical Society and its extensive collections. At its height the UCV had 1,885 local camps and 160,000 members. The UCV worked to honor the valor of and support the welfare of Confederate veterans and to keep alive their story of the history of the Civil War in statutes, publications, and institutions. The successor organizations to the UCV are the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) still active today and dedicated to the same purposes.

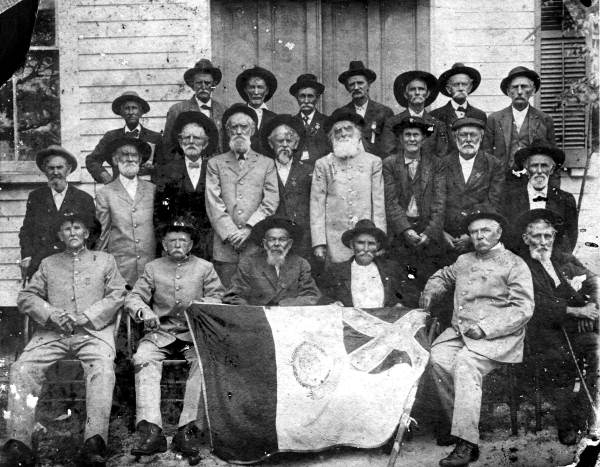

Confederate Veterans Reunited for Group Portrait – Crawfordville, Florida, 1904.

Photograph Courtesy of: Florida Photographic Collection, State Library and Archives of Florida

Confederate veteran groups began forming as early as 1865. The premier Confederate veterans’ organization, the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) was formed June 10, 1889 and dissolved formally May 30, 1952, after the death of its last member. The UCV was a non-military, educational, social, historical organization concerned with the welfare of its members. Activities included raising funds for and constructing monuments commemorating Confederate heroes and battles, researching and publishing histories, and building Battle Abbey, now the home of the Virginia Historical Society and its extensive collections.

From a newspaper article about the war and the South at the end of the war:

A Retrospect: A living contradiction to all past examples of history; a bright reality to be striven for by mankind in the future, but never to be attained again, its isolation will increase its splendor as one star alone in the heavens shines brighter when its fellows are hidden. To us of the generation will be the pride of having lived at such a time; upon us will rest the humiliation of having lost it by our own deep folly and crime. [1]

In the spring of 1865 the veterans wanted to get home and, perhaps, get a crop in before winter. The early years after the war were very difficult, the South had changed in so many ways. The antebellum South was, as many wrote, like a dream. The reality of the hard life immediately after the war was, for many, the reality of the rest of their lives.

Right after the war there were some early veteran groups often based on the military units which they had been part of during the war. As an example, in 1865, the Oglethorpe Light Infantry Association in Savannah was one of Georgia's earliest military veteran organizations. Another example is the Confederate Survivors' Association (CSA) based in Augusta Georgia and active from 1878 until just before World War II.

A local Association of the Army of Northern Virginia was founded in 1870 by a small group of ex-officers, as was The Robert E. Lee Camp which created the first soldiers’ home in the south, inspired perhaps by the soldiers’ homes supported by the federal government in the North. The Grand Camp of Confederate Veterans of Virginia was another organization in Virginia, Tennessee and Georgia. For most, especially in the South, just surviving was a full-time job leaving little time for remembering. Also, in contrast to the North, the veterans in the South did not have the support of the federal government and much of the South was in great disarray. Growing crops, restoring most of the railroad system, and rebuilding much of the infrastructure of cities, manufacturing and trade needed to be accomplished before memories of the war would be addressed.

In the North, as time passed, and the pain of the war faded, an interest in remembering the war grew. The 1870s was the period in which the northern veterans started forming their various groups with the first major reunions starting in the 1880s. Members of the local and regional veterans’ groups in the South saw what was happening and responded with the suggestion that a southern organization like the Union veterans’ organization, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), was needed.

The effort of the federal government to change the social structure of the South with Reconstruction is the backdrop to all the history of this period after the Civil War. The Grant administration was very concerned about activity in the South and the resistance to change there, which included violence against Republicans and freed people as well as lingering concerns that full-scale war could break out again. The Grant Administration decided that there was a southern effort to resist congressional Reconstruction. The government was able to suppress the Ku Klux Klan through the Force Acts of 1870-71. But the congressional report on southern Reconstruction in 1872, stated that the effort to resist was continuing and that paramilitary insurgents were organizing. This included the Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, the White League in Louisiana, and other groups, that used violence as well as other means, to stop or reduce voting by blacks. [2]

This led to the return to power in the South by the Democrats in the late 1870s, and the suppression of the goals of Reconstruction that lasted until the 1960s. The federal Reconstruction program and the state of the southern economy slowed the formation of Confederate veterans’ organizations, but finally in 1889 a national association, the United Confederate Veterans, was formed.

The pressure against Confederate veterans organizing is reflected in this paragraph from the UCV reunion Program in 1905:

For some years after the close of that war, whenever the old soldiers of the South assembled for a peaceful celebration of some historic anniversary, there was a great outcry throughout the North that the Confederacy was again organizing, and that some new treason or trouble was to be expected. But that foolish and unfounded dread was wholly dissipated when the men of the South, old and young, eagerly volunteered for the service of the Republic in the war with Spain, and the two sections were made one forever when Joseph Wheeler, Fitzhugh Lee and others of the prominent figures of the South in the Confederate War were appointed to be General Officers with corps and division commands in the Army of the United States. [3]

In the 1870s and 1880s interest in a coming together of northern and southern veterans grew among businessmen and politicians. This development was slowed because for southerners the issue of the return of captured southern battle flags and for northerners the use of the Confederate battle flag at veterans’ events stood in the way. This conflict over battle flags continued as long as there were veterans of the war alive. In addition, Republicans in the North in this period were worried that the Democrats in the South, veterans or not, would attempt to regain power in the national government and thus reverse the outcome of the Civil War. For southern Democrats, the concern was that the GAR was an undeclared wing of the Republican Party. All this greatly reduced the number of joint veterans’ programs held in this period.

Formation of United Confederate Veterans, June 10, 1889

The United Confederate Veterans was formed on June 10, 1889 and dissolved on May 30, 1952. The UCV published The Confederate Veteran which became one of the most popular magazine published, with a large circulation, perhaps for a time the largest in the South. The last issue was published in December 1932. It included articles on the many problems the UCV was experiencing, the advanced age of the veterans and the financial problems caused by the depression and how it affected the membership. Also, this last issue discussed the United Daughters of the Confederacy, their efforts to keep the UCV camps open and the help they had given to the magazine over the years. [4]

The first convention to organize the United Confederate Veterans took place in New Orleans, Louisiana June 10, 1889. [5]

The purposes of the organization are outlined Appendix 2 Constitution of the United Confederate Veterans. They intended to be a non-military, educational, social, historical organization and concerned with the welfare of their members. There were fifty-two delegates from nine separate veterans’ organizations at this first meeting. At its height, the UCV had 1,885 UCV local camps and a total membership in the UCV approached 160,000 or approximately 25 percent of the southern soldiers who survived the Civil War. The organizational structure of UCV was based on a military hierarchy, with a national office, three departments, divisions within the departments and local camps; there were appointed officers throughout the entire association. An Adjutant General's office awarded commissions to members. [6]

The United Confederate Veterans wanted a structure that was not dependent on leaders but rather one that could function over the years. At the organizational convention, they designed a structure and constitution meant to foster the future success of the organization.

First National UCV Annual Meeting and Reunion 1890

The first annual meeting and reunion of the United Confederate Veterans took place in the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee. July 3, 1890.

The United Confederate Veterans elected John B. Gordon Commanding General and George Moorman Adjutant General. Moorman is often written about as being the person that was the head of the UCV and Gordon the heart and together they would not accept failure for the organization. The meeting laid out the rationale for the creation of the UCV. This included a desire to demonstrate esteem and admiration for the courage of Confederate soldiers while some were still alive. Foreshadowing a growing commitment to erecting monuments to the Confederacy, the rationale included erecting a statue to Jefferson Davis in New Orleans. Only later did the UCV begin to become concerned with promoting the welfare of its members and publishing histories of the war from the Confederate viewpoint.[7]

From this first convention, the UCV grew very quickly and had 1,565 camps in 1904 with about 80,000 members. The largest percentage of camps were in Texas. The UCV was very active for the next 10-15 years after which the numbers of surviving veterans started to decline precipitously.

The Veterans were very aware that they were ageing and would slip away in only a few short years. They were concerned about saving the history and the story of the quality of the Confederate veterans so even at this early time, they started forming permanent organizations of sons and daughters.

The local camps would meet once or twice a year, not so much for aiding the veterans, or sponsoring historic projects but for social purposes. From the beginning, most camps experienced a shortage of funds and this also affected the national association’s ability to operate.

There was a strong interest in the national reunions and they were very popular with the public in the South. The numbers showed about twice as many non-members as members at the national reunions and the decline in surviving veterans as the years went by increased this disparity. The largest national UCV reunion was held in Little Rock, Arkansas in May 1911 and attracted over 100,000 veteran participants.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc. is an association of male descendants of Confederate veterans. It was founded July 1, 1890. Its original mission was simply to "honor the memories of those who served, promote knowledge, and cultivate the ties of friendship that should exist among descendants of Confederate soldiers". [8]

United Daughters of the Confederacy, Inc. is an association of female descendants of Confederate veterans. It was founded September, 1894. Its original mission was to "honor the memories of those who served, promote knowledge, and cultivate the ties of friendship that should exist among descendants of Confederate soldiers". [9]

Third National UCV Reunion 1892

The third national UCV reunion was held in New Orleans, Louisiana, April 8-9, 1892. The 1892 Program describes how the meeting, run by Major General John Brown Gordon invited General James Longstreet to sit in a place of honor on the platform where he was greeted with a standing ovation. Longstreet had been a source of controversy after the war and his inclusion on the UCV platform marked a closing of bitter political differences and arguments over interpretation of events during the war among the remaining Confederate veterans.

At the end of the meeting, there was a grand parade and a review of thirty thousand old veterans and leaders who marched in the parade. Two hundred thousand citizens of New Orleans and visitors watched the parade.[10]

The History of the War and the UCV

The United Confederate Veterans were involved with many projects, both to honor the past and to direct the study of the War.

One concern was to see that there were text books that reflected the Confederate point of view of the Civil War and the South as this example from the fifth national UCV reunion shows:

The histories written by Northern historians in the first ten or fifteen years following the close of the war, dictated by prejudice and prompted by the evil passions of that period (and generally used in the schools) are unfit for use, and lack all the breadth, liberality and sympathy so essential to true history, and although some of them have been toned down, they are not yet fair and accurate in the statements of facts. Many of these histories have an edition for use in Northern schools and another of the same history for use in Southern schools toned down and made to pander, it is supposed, to Southern sentiment. What is needed is a history equally fitted for use North and South and divested of all passion and prejudice incident to the war period. Until a more liberal tone is indicated by Northern historians, it is best that their books be kept out of Southern schools.[11]

In 1899 the publication of Clement A. Evans, ed., Confederate Military History, A Library of Confederate States History, 12 vols. (Atlanta, GA: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899) addressed some of the perceived continuing educational problems as did history courses in public schools and chairs of history in southern colleges.

Seventh National UCV Reunion 1897

General Gordon had been Commander of the organization from the beginning. He wanted to announce in 1897 at the seventh national UCV reunion, that he did not wish to continue in that position.

As he attempted to announce his resignation after eight years’ service leading the UCV, General Gordon’s words were drowned out by the veterans objecting and demanding he remain their leader. Eventually he was able to speak, and he celebrated the growth of the UCV which at that point had over 1,000 organized camps. He did not, however, resign as the Commander. General Gordon remained as Commander of the organization until the end of his life and died January 1904 and was celebrated throughout the South and North with 40,000 attending his funeral, with messages from many including President Theodore Roosevelt. [12]

At this UCV convention Charles Broadway Rouss of New York offered $100,000 for the erection and establishment of the Battle Abbey, providing the veterans raised a like amount. Construction began in 1912 and the first part was completed in 1913 by the Confederate Memorial Association as a shrine to the Confederate dead and a repository for records of the Lost Cause. Today the much-expanded Battle Abbey is the home of the Virginia Historical Society and houses its extensive collections.

Eighth National UCV Reunion 1898

At the eighth national reunion and encampment Camp John W. Gordon was established, and the veterans lived in tents, recalling their life in the army. One veteran told a reporter, "Yes, I like it out here. It gives me the last glimpse I will ever have in this life of the old times when we marched and fought under Marse Bob.” [13]

Eleventh National UCV Reunion 1901

Lieutenant Dugan, of South Carolina, while a prisoner at Johnson's Island, Sandusky, Ohio with 3,000 of his comrades developed a march to fight boredom and stay warm, called the Southern Cross Drill. It was set to music and performed as a square dance. General George W. Gordon who was also a prisoner at Johnson's Island danced it there with the other prisoners, and it was he who introduced this drill at the reunion at Memphis in 1901. It was a part of the national reunions for years after its introduction. [14]

At the 1901 reunion veterans were treated to stereopticon pictures which were accompanied by southern songs by the Confederate Choir— Old Kentucky Home, Suwannee River, Dixie, Maryland and others. An estimated 10,000 veterans paraded in a line of march four miles long and cheered by 200,000 onlookers. [15]

Confederate Cemeteries and Monuments

Another point of concern for UCV members was the number Confederate prisoners who had died in confinement as well as the number buried and where in each northern state. Later there was concern as to who would preserve the headstones and the records of the dead.

First introduced in 1902 and eventually enacted in 1906 was a Senate bill to supply $200,000 for the acquisition of burial-grounds by the United States Government and erecting suitable headstones for Confederates buried in northern cemeteries. This ended the ongoing discussion of the fate of Confederate fallen in the North and the care and maintenance of the stones and monuments became a federal responsibly.

We care not whence they came, Dear is their lifeless clay. Whether unknown, or known to fame, their cause and country still the same, they died—and wore the gray. [16]

The Monument Committee of the UCV was involved in the design, purchase and raising of funds for many commemorative plaques and monuments in the South. Funds were raised from all UCV camps to build the Jefferson Davis Monument in Richmond, Virginia, which was completed in 1910.

Lieutenant-General Stephen D. Lee, spoke at the dedication of the Jefferson Davis Monument saying, "The people who do not cherish their past will never have a future worth recording." [17]

Twenty-Seventh National UCV Reunion 1917

With the impending war in Europe and America’s involvement in it, the federal government approached the 1917 convention in Washington, as an opportunity to encourage the southern states and veterans to support the war effort.

This twenty-seventh national UCV reunion in Washington D.C. on June 5-7, 1917 was one of the more important in its history because the UCV was at last recognized by the federal government as an organization that was needed for the upcoming war effort.

At this reunion the United Confederate Veterans and the Grand Army of the Republic came together to support the American war effort. The Commander of the GAR, James Tanner spoke to the UCV as did Harry Lee, their Commander. President Woodrow Wilson was present and spoke to the assembled veterans. During the flag ceremony the Marine Corps Band played the Star-Spangled Banner and then Dixie. The Confederate veterans marched up Pennsylvania Avenue and hundreds of daughters and sons marched with them offering physical support to the old men. More than 30,000 people marched in the parade which was watched by “hundreds of thousands” of well-wishers. [18]

After World War I

After the end of World War I the UCV focused on telling what they saw as the true history of the Civil War

The 1919 Historical Committee, later called the Rutherford Committee, was formed at the 1919 reunion and was tasked with imparting the “truth” of Confederate history. One of the key motivations driving veterans’ groups (on both sides) to work to enshrine their stories in textbooks, monuments, and elsewhere, was the sense that new generations were emerging who had no actual experience of the war which was becoming more of an historical event than a recent one. This generational shift spurred veterans to try to make sure that their version of the war would be accepted as truth by younger people.

The 1920 reunion saw greetings from the American Legion members and WW I veterans. They discussed the idea of receiving pensions from the federal government. A resolution was passed for the federal government to print and save Confederate material now in their care and another was passed for the movement of Sarah Knox, the first wife of Jefferson Davis, and daughter of Zachary Taylor to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond were passed.

The reunions continued through the 1920s with a gradual reduction in membership. The preamble to the 1926 the convention stated that the time was rapidly approaching when it would not be possible for the Confederate Veterans to transact business in the best interests of the organization due to age and infirmity. It was resolved that a joint committee be appointed by the United Confederate Veterans, the Daughters of Confederate Veterans and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Recognizing the thinning membership and increasing infirmities of living members and calls for sympathy and assistance from the Sons and Daughters of Confederate Veterans, a plan was made by which the affairs of the Confederate veterans associations might be perpetuated. It was also decided that as long as a Confederate veteran was left, the Honorary President of the UCV would be a Confederate veteran, but the active president would be either a son of a Confederate veteran or a daughter of a Confederate veteran.

The UCV experienced financial difficulties during this period from declining membership and slow remission of dues from the camps. The financial problems worsened during the Great Depression.

Thirty-Ninth National UCV Reunion 1929

In the late 1920s there was an ongoing discussion between the GAR and the UCV about a joint reunion. The discussion revolved around the Stars and Bars flag and the GAR refused to hold a joint reunion. Reaction among the Confederate veterans was mixed, some disappointed, others not wanting a joint reunion.[19]

Fortieth National UCV Reunion 1930

In the 1930 reunion the Veterans passed a resolution, which was adopted, thanking President Hoover for sending the United States Marine Band to the reunion. The arguments over holding a joint session of the UCV and GAR continued and the UCV rejected the GAR suggestion to retire the Confederate flag to museums and insisted that they would always march behind the Stars and Bars.

There are examples of veterans on both sides who were receptive to the idea of a reunion and of the majority who were not. Through the years in general, one of the major points of anger on both sides was the Stars and Bars. The southern flag was and still is a lightning rod for emotions. From the 1870s to the end of both organizations there were only perhaps a dozen joint meetings. [20]

In 1932 the Confederate Veteran Magazine ceased publication. By this time, much of the day to day active administration of the UCV was being handled by the SCV and DCV organizations as was clearly illustrated in the print material.

Forty-Third National UCV Reunion 1933

The Gettysburg Chamber of Commerce issued an invitation to the United Confederate Veterans to hold their 1933 reunion in Gettysburg, in observance of the 70th anniversary of the battle. Financial difficulties in the late 1920s compounded by declining membership and the Great Depression ultimately led to the cancellation of the 1933 reunion. Commander-in-Chief Atkinson made a public announcement that they had failed to locate a community large enough where sufficient funds could be raised to finance the reunion. As a gesture of cordial friendship and in a spirit of friendly cooperation, the directors of the Gettysburg Chamber of Commerce, at their April meeting, voted unanimously to extend the invitation when it was learned that the United Confederate Veterans were financially unable to hold their convention that year

Forty-Fourth National UCV Reunion 1934

General Rice A. Pierce, 87 years, who fought under Nathan Bedford Forrest was elected Commander in Chief of the UCV in 1934. Marshall Thompson, a Negro valet of Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry staff, told an anecdote of how Forrest "showed "a West Point general" what "a corn-fed general" could do. Thompson's story, which coincides with historical data, follows in his own words: "We was trapped in Fort Donaldson and General Forrest he, was arguing about the best way for our cavalry regiment to git out. "Gineral Forrest 'lowed de best way was off to de left, but one of his staff said: No, Gineral, they's a West Point Gineral guardin' that corner for de Yankees.' "Gineral Forrest riz in his stirrups and yelled: "'Hell, he's the very damn man I'm lookin" faw—I'm goin' show lim what a corn-fed gineral can do.' "Dey lit out at a gallop — and dey got through." [21]

Forty-Fifth National UCV Reunion 1935

The meeting in in 1935 took place in Nashville, Tenn. General Harry Bene Lee was elected commander, an interesting veteran who after the Civil War needing more excitement joined the British Navy and served all over the world. The Pennsylvania State Commission for the observance of the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, proposing there should be a joint reunion in Gettysburg in 1938, extended official invitations to the United Confederate Veterans and the Grand Army of the Republic. The United States Marine Band were also there for the 1935 reunion. Aged Confederate veterans straightened and cheered the declaration that they would meet as long as there were three of them left. The convention voted unanimously to accept the invitation to meet in a joint reunion at the Gettysburg battlefield in 1938. The Confederates included the provision that they be permitted to fly the Stars and Bars at the meeting. [22]

Forty-Sixth National UCV Reunion 1936

The 1936 reunion was held June 9, 1936 in Shreveport Louisiana. The Star-Spangled Banner was played by the US Marine Band when the 46th annual reunion opened. Shreveport surrendered on June 11, 1865 and on the anniversary of the surrender a special ceremony was held on the court house square. Singing I'm an Old Time Confederate the veterans then gave the famous rebel yell.

A secession movement which threatened to split the United Confederate Veterans, took place at the end of the convention with the threatened departure of General John W. Harris, for Oklahoma City, to form a western department of Confederate veterans. The possible rift in the veterans' group came at the closing session. It was precipitated by the election of General Homer Atkinson of Petersburg, Virginia as Commander-in-Chief over J. M. Claypool, of St. Louis. According to Harris, the western section would secede from the eastern group because the eastern states were attempting to control the organization. The veterans of Forrest, Lee and Jackson, all around the age of ninety, engaged in a verbal battle with clenched and pounding fists. Ultimately the schism was avoided. [23]

Forty-Seventh National UCV Reunion 1937

As the United Confederate Veterans had voted to meet in joint reunion with the Grand Army of the Republic in Gettysburg in 1938 during the observance of the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, a wave of sentiment and enthusiasm grew among the veterans. One veteran said "There isn't any use to hate your enemies. I like a good fight; but when it's over I'm ready to shake hands. And that's what we'll all do at Gettysburg." [24]

The closing parade found only two of the 200 veterans able to march, the others riding in automobiles, waving feebly to the cheering throngs lining the streets. General Harry Rene Lee, retiring Commander-in-chief of the veterans and General Homer T. Atkinson, new elected Commander rode together near the head of the parade. Large crowds cheered the thinning ranks of the veterans as the parade covered its course, while bands blared the songs of the Confederacy.

National Gettysburg Memorial Event and Forty-Eighth National UCV Reunion 1938

The 1938 National Gettysburg Memorial Event and national UCV reunion was held at Gettysburg Pennsylvania on July 2-6, 1938 with 2,250 of the approximately 8,000 Civil War veterans still living. An estimated 10,000 persons thronged the Gettysburg College stadium for the program.

The 1938 forty-eighth national UCV reunion was held August 30-31, 1938 in Columbia South Carolina with the assistance of the American Legion and the United States Marine Band. The Sons of the Confederate Veteran’s held a ball one evening and the UCV held a ball on the second evening. The veterans elected General John W. Harris of Oklahoma City, their Commander. The Convention ended with the grand parade—a march down Columbia's main street to the state capitol, which still bore the scars of shelling by General Sherman's Union army.

Forty-Ninth National UCV Reunion 1939

The 1939 reunion, held at Trinidad, Colorado, August 22-25, 1939, was attended 'by only a small number of surviving veterans, whose ages ranged from 90 to 97. The United States Marine band opened the 49th reunion with the national anthem and then swept into the traditional Dixie and 95-year-old Major General R. P. Scott of Dallas did a lively heel and-toe to the rousing music. [25]

Fiftieth National UCV Reunion 1940

The few surviving veterans met in Washington D.C. and greeted President Roosevelt during a visit to the White House. [26]

Fifty-first National UCV Reunion 1941

The reunion in 1941 took place in the fall of that year and the Confederate veterans gave a strong endorsement of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his foreign policies.

There was an open conflict in the press between the standing Commander Julius F. Howell who did not want to hold a reunion in 1941 and three past commanders who believed they had the right to organize the program in Atlanta and did so. A visitor to the Atlanta reunion was the son of General John Bell Hood.

The Kansas City Times strongly supported the Confederate veterans and their stand on the problems facing the nation and the possible conflict in the future, writing that the veterans were an inspiration to the young men of the nation. [27] Margaret Mitchell, who wrote Gone with the Wind was the sweetheart of the UCV reunion. After Miss Mitchell was introduced the band broke into Dixie and the veterans crowded around to pay her compliments and shake her hand. [28]

Fifty-third National UCV Reunion 1943

The 1943 convention was canceled because of travel restrictions and the many other issues caused by the war. General Homer Atkinson Commander-in-Chief wrote, “We gladly forgo the happiness implicit in our annual gatherings and by self-denial and in every possible form of service give wholehearted support to every agency of our country in this supremely tragic hour.” [29]

General Longstreet's widow at 80 was working in a defense plant, Helen Dortch Longstreet lived a long and eventful life. At the age of 80, she gained national publicity and had an article published in Life Magazine in 1943 featuring her efforts and the story of her late husband General Longstreet. She served as a Rosie the Riveter, building B-24 Bombers at the Bell Aircraft plant in Marietta, Georgia during World War II. She said at the time, "I am going to assist in building a plane to bomb Hitler." She was living in a small trailer, and when her employer became concerned about her age she said, “I've been an assembler and riveter for about two years and have never lost a day from work or been a single minute late. I will quit only when the last battle flag has been furled on land and sea.” [30]

Fifty-fourth National UCV Reunion 1944

MONTGOMERY. Ala., Sept. 27 1944. A few of the remaining men of the confederate army assembled here today for the 54th annual meeting of the United Confederate Veterans. September 27-28. Only about 12 to 15 of the old soldiers were expected to attend the reunion, held in conjunction with the two-day conventions of three other organizations—The Sons of the Confederate Veterans Confederate Southern Memorial Association and the Order of Stars and Bars. [31]

The World's Best On Confederate Memorial Day in Atlanta, Ga. Four men who fought for the South stood in the reception room of the Confederate Soldiers Home and sent a message to the men who are battling today for their country. They stood as straight as possible for them to stand, their eyes snapped as they thought back to the war they fought so many long years ago. Gen. H. T. Dowling, Commander of the United Confederate Veterans of Georgia, really sent the message. He is spry, and he keeps up with the news from hour to hour as he listens to the radio and reads the newspapers. "You tell the boys," he said, "that we're pleased with the way they're battling. The war seems to be going real well, though things are different today when they were when we were fighting. We just had small arms, and took it man to man, but when it came to killing we were as good as they are today." Thus from one generation of fighting men to another went a greeting—one of pride in the accomplishments of an army that is victorious. From Confederates to Americans of 1944, "We're pleased with the way you're fighting." The nation might well take the words of this aged man and echo them around the world. "We're pleased, men. You couldn't do it any better. You're tops. [32]

Fifty-fifth National UCV Reunion 1945

“President Truman at the White House greeted General Julius F. Howell of Bristol, Virginia, the 99-year-old Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans.” [33]

The fifty-fifth reunion was held at Chattanooga Tennessee. Seven soldiers elected General W. William Banks of Houston, Tex. Commander in Chief of the United Confederate Veterans replacing General Julius F. Howell. On June 11, 1945 General John Milton Claypool, 98, twice national commander-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans, died of pneumonia. Commander Claypool declined to lead Confederate veterans at a joint reunion of the UCV and GAR on the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg unless his men were allowed to wear their uniforms and display their flags. [34]

Fifty-sixth National UCV Reunion 1946

South Carolina offered free transportation for any Confederate soldier in South Carolina physically able to make the trip to the reunion. Henry T. Dowling was elected national Commander-in-Chief. United States Senator James O. Eastland of Mississippi was a principal speaker. There were only 112 veterans left and all were invited. They discussed converting the Jefferson Davis home which had served as a home to veterans but only had one widow living there at the time, to a shrine for the late Confederate President. No parades or picnics were scheduled, but there were a number of free trips to Civil War sights along the coast and to the former home of Jefferson Davis.

A new committee was struck and tasked with preserving the literary and historical materials of the Confederate South.

Attending the reunion were William Freeman 102, Oklahoma, William Mercer Buck 96, Oklahoma, William W Alexander 97, South Carolina and James W Moore 96, Alabama. [35]

Fifty-seventh National UCV Reunion 1947

In 1947 the commander in chief General Henry Dowling of Atlanta was unable to attend because of illness, though he sent greetings. On October 10, 1947 the new commander-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans, William Mercer Buck of Muskogee, Okla., was seriously injured in an automobile wreck near Waynesboro, Tenn.[36]

Fifty-eighth National UCV Reunion 1948

In 1948 the new Commander of the United Confederate Veterans was 97 years old, but he still drove his own automobile. General J. W. Moore drove his car from his home at Selma, Alabama 50 miles to Montgomery for the 1948 Confederate reunion. Two other Confederate veterans also attended, but General Moore's predecessor General William Mercer Buck was not able to make it from his home at Muskogee Oklahoma as he was still recovering from his automobile accident.

The three remaining veterans decided to meet next year at Little Rock.[37]

The GAR reunion of 1949 was the final encampment. Six union veterans had attended and agreed that they would not meet again. The Union veterans sent official GAR greetings to the UCV for their 59th encampment. [38]

Fifty-Ninth National UCV Reunion 1949

Of the twenty-eight surviving Confederate veterans, three attended the reunion and recalled their wartime experiences, 102-year-old James A. Thrasher of Mississippi, General James W. Moore of Alabama 98 the United Confederate Veterans Commander-in-Chief and W. Alexander 100 of South Carolina. There were two concerts by the U.S. Marine Corps Band. General James W. Moore was re-elected Commander-in-Chief.

Sixtieth National UCV Reunion 1950

Confederate Rebel Yell to Be Recorded For Congress Library

Plans to perpetuate the old battle cry through recordings to be placed in the Congressional library were made here yesterday to a joint reunion of five Confederate organizations. Hatley Norton Mason of Richmond Va., Adjutant-in-Chief of the Sons of Confederate veterans, said he hopes recordings can be made of the rebel yell as given by each of the known surviving Confederate veterans asked to make the recordings. Mason outlined the plan at a joint reunion of the United Confederate veterans, the Sons of the Confederacy, the Sons of Confederate Officers, The Order of the Stars and Bars, and the Confederate Memorial Association. [39]

Though other Confederate organizations such as Sons of Confederate Veterans, the Confederate Southern Memorial Association and the Order of the Stars and the Bars were present, of the 18 Confederate veterans still alive, only General James W. Moore, the 98-year-old commander attended from the UCV.

Sixty-first National UCV Reunion 1951

Twelve Confederate veterans were known to be living in 1951, at the time of the 1951 UCV reunion. Replicas of the nation's first ironclad warships, the "Monitor" and the "Merrimack," re-enacted their famous battle in Hampton Roads 89 years ago. The mock battle was a highlight of the 51st reunion of the United Confederate Veterans. Three veterans attended.

The final UCV Commander-in-Chief, General James W. Moore, (January 3, 1852-February 26, 1951) passed away. James had joined Morgan's Partisan Rangers as a member of Wheeler's Cavalry at 13. He was sent home after a year. Later he attended and graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in 1873.

The last verified UCV Veteran to die was Mr. Pleasant Camp, who died on December 31, 1951 at the age of 104. A native of Alabama, he enlisted in 1864, fought in Virginia and was at the Appomattox surrender.

Sixty-second and Final National UCV Reunion 1952

One final meeting of the United Confederate Veterans was held at the 1952 convention of the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, who in solemn conclave, voted to end the official existence of the United Confederate Veterans of America.

At its height, the United Confederate Veterans had 1,885 local camps and 160,000 members. The UCV worked to honor the valor of and support the welfare of Confederate veterans and to keep alive their story of the history of the Civil War in statutes, publications, and institutions. The successor organizations to the UCV are the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) still active today and dedicated to the same purposes.

- [1] Louisville Democrat, April, 17 1865.

- [2] From Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 139-56 and Scott Poole, Never Surrender (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 122.

- [3] Fifteenth National UCV Program, Louisville, Kentucky, 14-16 June 1905. The UCV published their National UCV Programs annually. They were a form of commemorative booklet, a printed description of the annual meetings which functioned as minutes and generally ran to 60-100 or more pages. The complete text of some of the Programs is available on line and included in the Resources material for this topic; For additional evidence of the pressures against the UCV see "United Confederate Veterans," Confederate Veteran 1, no. 1 (January, 1893): 11.

- [4] “The Veteran Passes, The End Is Here,” Confederate Veteran, 40, no. 1 (January 1932): 412.

- [5] Organizational meeting of the United Confederate Veterans Program, New Orleans, Louisiana, 10 June 1889.

- [6] Casualty and enlistment figures are notoriously difficult to establish and changing with new scholarship. If we assume that there were 880,000 Confederate soldiers and 260,000 casualties, both commonly accepted figures, then 160,000 members of the UCV would represent approximately 25% of the Confederate soldiers who survived the war.

- [7] Ibid.

- [8] The mission of the SCV has changed over time and currently is as follows: We have a threefold mission: First to develop and implement strategies for sustained growth, second to train our leadership and educate our members to reclaim our Southern Heritage and our American Liberty and Third to proclaim to the world the truth concerning the War for Southern Independence and the Confederacy. From http://www.scv.org/new/what-is-the-scv/scv-vision-power-point/ accessed June 24, 2019.

- [9] The mission of the UDC has changed over time and currently is as follows: The objects of the organization are Historical, Educational, Benevolent, Memorial and Patriotic: To collect and preserve the material necessary for a truthful history of the War Between the States and to protect, preserve, and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor. To assist descendants of worthy Confederates in securing a proper education. To fulfill the sacred duty of benevolence toward the survivor of the War and those dependent upon them. To honor the memory of those who served and those who fell in the service of the Confederate States of America. To record the part played during the War by Southern women, including their patient endurance of hardship, their patriotic devotion during the struggle, and their untiring efforts during the post-War Reconstruction of the South. To cherish the ties of friendship among the members of the Organization. From https://www.hqudc.org/about/ accessed June 24, 2019.

- [10] Third National UCV Reunion Program, New Orleans, Louisiana, 8-9 April 1892.

- [11] Fifth National UCV Reunion Program, Houston Texas, 22-24 May 1895.

- [12] Seventh National UCV Reunion Program, Nashville, Tennessee 22-24 June 1897.

- [13] Eighth National UCV Reunion Program, Atlanta, Georgia, 20-23 July 1898.

- [14] Eleventh National UCV Reunion Program, Memphis, Tennessee, 27-30 May, 1901.

- [15] Eleventh National UCV Reunion Program, Memphis, Tennessee, 27-30 May 1901.

- [16] Ibid.,

- [17] Sixth National UCV Reunion Program, Richmond, Virginia, June 30 – July 2, 1896, 163.

- [18] Richard Beamish, "Confederate Parade Up Pennsylvania Avenue." Philadelphia Press, June 7, 1917.

- [19] Thirty-Ninth National UCV Reunion, Charlotte, North Carolina, 1929.

- [20] Fortieth National UCV Reunion, Biloxi, Mississippi, 3-6 June 1930.

- [21] Forty-Fourth National UCV Reunion Program, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 6-8 June 1934.

- [22] Forty-Fifth National UCV Reunion Program, Amarillo, Texas, 3-6 September 1935.

- [23] Forty-Sixth National UCV Reunion Program, Shreveport, Louisiana 9-12 June 1936.

- [24] Forty-Seventh National UCV Reunion Program, Jackson, Mississippi, 9-12 June 1937.

- [25] Forty-ninth National UCV Reunion, Trinidad, Colorado, 22-25 August 1939.

- [26] Fiftieth National UCV Reunion Program, Washington D.C. 8-11 October 1940: “Confederate Veterans Resent Women's Efforts to Rule Their Meetings,” San Antonio Express, October 11, 1940; “Rebel flag at White House,” Abilene Reporter News, October 10, 1940.

- [27] Kansas City Times, October 27, 1941.

- [28] Fifty-first National UCV Reunion Program, Atlanta, Georgia, 14-15 October 1941; “1941 Confederate Reunion Illegal,” Kingsport Times, October 9, 1941; “Margaret Mitchel, Who Wrote Gone with the Wind Is Sweetheart of UCV Veterans Meet,” McAllen Daily Press, October 15, 1941.

- [29] Kingsport Times, August 25, 1943

- [30] "Gen. Longstreet's Widow," The Atlanta Journal, October 12, 1943.

- [31] Northwest Arkansas Times, June 20, 1944.

- [32] Fifty-fourth National UCV Reunion Program, Montgomery, Alabama, 27-28 September 1944.

- [33] "Fifty-fifth UCV Reunion," Abilene Reporter News, 26 September 26, 1945.

- [34] "UCV to Meet," Big Spring Day Herald, September 26, 1945.

- [35] Fifty-sixth National UCV Reunion Program, Biloxi, Mississippi, 7-8 October 1946.

- [36] “Three Boys in Gray on Scene for UCV Meet,” Kingsport Times News, October 7, 1947; “Confeds Close Reunion,” Florence Morning News, October 9, 1946; “William Buck 96 Named UCV Chief Only Four Attend," Kingsport Times, October 9, 1947.

- [37] Bradford Era, October 20, 1948.

- [38] “Returning Home for the Last Time,” Kenosha Evening News, September 1, 1949.

- [39] “Confederate Rebel Yell to Be Recorded for Congress Library,” Thomasville Times Enterprise, September 29, 1950.

If you can read only one book:

Janney, Caroline E. Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Downloads:

- Confederate Veterans' Associations Essay

- Confederate Veterans' Associations Essay Appendix 1 Reunions and Commanders in Chief

- Confederate Veterans' Associations Essay Appendix 2 Constitution of the United Confederate Veterans

- Confederate Veterans' Associations Resources

- Author's Biography James L. Johnson

Books:

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2001.

Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Foster, Gaines M. Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Harris, M. Keit. Across the Bloody Chasm: The Culture of Commemoration among Civil War Veterans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Janney, Caroline E. Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Logue, Larry M. and Michael Barton. The Civil War Veteran: A Historical Reader. New York and London: New York University Press, 2007.

Marten, James Alan. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

McClurken, Jeffrey W. Take Care of the Living: Reconstructing Confederate Veteran Families in Virginia. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009.

Poole, Scott. Never Surrender. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

Rosenburg, R.B. Living Monuments: Confederate Soldiers’ Homes in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Organizations:

Sons of Confederate Veterans

The Sons of Confederate Veterans is one of the two successor organizations to the United Confederate Veterans. Its mission is to preserve the history and legacy of the citizen-soldiers who fought for the Confederacy, so future generations can understand the motives that animated the Southern Cause. Organized at Richmond Virginia in 1896, the SCV serves as a historical, patriotic, and nonpolitical organization.

United Daughters of Confederate Veterans

The United Daughters of Confederate Veterans is one of two successor organization to the United Confederate Veterans and the outgrowth of many local memorial, monument, and Confederate home associations and auxiliaries to camps of United Confederate Veterans that were organized after the War Between the States. The objects of the organization are Historical, Educational, Benevolent, Memorial and Patriotic:

- To collect and preserve the material necessary for a truthful history of the War Between the States and to protect, preserve, and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor

- To assist descendants of worthy Confederates in securing a proper education

- To fulfill the sacred duty of benevolence toward the survivor of the War and those dependent upon them

- To honor the memory of those who served and those who fell in the service of the Confederate States of America

- To record the part played during the War by Southern women, including their patient endurance of hardship, their patriotic devotion during the struggle, and their untiring efforts during the post-War reconstruction of the South

- To cherish the ties of friendship among the members of the Organization

Web Resources:

The University of Pennsylvania has Minutes of the Annual Meetings and Reunions of the United Confederate Veterans available to be read online for Reunions 1-24, 27, 30 and 36.

Other Sources:

Confederate Veteran

The Confederate Veteran was the magazine published by the United Confederate Veterans from 1893-1932. The University of Pennsylvania has made copies of all issues available for free.

The UDC Magazine and its predecessor the United Daughters of the Confederacy Magazine, is the publication of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. A subscription can be obtained from their website see the Resources document.

UDC Magazine

The UDC Magazine and its predecessor the United Daughters of the Confederacy Magazine, is the publication of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. A subscription can be obtained from their website.

Minutes and Reunion Programs of the United Confederate Veterans

Minutes and Reunion Program of the United Confederate Veterans Conventions, United Confederate Veterans 1889-1951., are available at University North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Library of the University of Texas.

United Confederate Veterans Association Records

United Confederate Veterans Association records are available at Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana.