Environment and the Civil War

by Matthew M. Stith

The natural and built environment directly shaped the course and outcome of the Civil War. Disease, weather, terrain, animals, food, and a host of other environmental factors were all inextricably tied to both large-scale campaigns and back yard battles across the South. The environment influenced critical engagements just as much as it affected civilian efforts to survive. It dictated guerrilla tactics as much as it influenced military and domestic supply systems. The environment molded the war, and the conflict shaped the natural environment. Environmental forces determined where, when, and how battles were waged and won, and they dictated the course of the war on the home front.

Introduction

The natural and built environment directly shaped the course and outcome of the Civil War. Disease, weather, terrain, animals, food, and a host of other environmental factors were all inextricably tied to both large-scale campaigns and back yard battles across the South. The environment influenced critical engagements just as much as it affected civilian efforts to survive. It dictated guerrilla tactics as much as it influenced military and domestic supply systems. The environment molded the war, and the conflict shaped the natural environment. Environmental forces determined where, when, and how battles were waged and won, and they dictated the course of the war on the home front. Hundreds of thousands of work animals and livestock perished in the war. Combatants cut down or blasted apart millions of trees. Controlled deforestation became a strategy for combating Confederate guerrillas, and felled trees fueled fires for large and small armies. Union commanders found that a successful war against the Confederacy meant also destroying the Confederacy’s built environment. The Civil War had become a war over and with the environment and it rapidly devolved into a series of particularly brutal, if localized, total wars amidst larger scale regular campaigns.

Union leaders harnessed control of the southern environment—and their own in the North—more effectively, and they consequently won the war. Although Confederates scored a number of victories thanks to their effective use of the landscape, they lost the war because they too slowly transitioned to a war-centered agricultural economy while trying to maintain control over their vast geographically and environmentally complex territory with too few men and supplies. The Federal army’s ultimate control over the southern environment did not always go smoothly, though. Northerners stumbled into numerous terrain-centered defeats and suffered massive casualties from the southern climate and accompanying disease. Yet the Union used its vast agricultural home front to great effect, and made a protracted and ultimately successful war not just on the Confederate army, but on the southern agricultural landscape. In the end, it was the Federal ability to control the environment—if at times haltingly and sloppily—that ensured Confederate defeat.[1]

Historiography

From a historiographical perspective, the environment’s role in the Civil War has heretofore been relegated to the margins. Civil War scholars have long recognized in the periphery the functions played by terrain, weather, disease, and food in shaping war and society, but they have only recently begun to view the conflict with an environmental perspective. The first real call to arms urging scholars to view the Civil War through an environmental lens came from Jack Temple Kirby who argued in 2001 that “the Civil War was a ‘total’ one—that is, unrelenting violence against not only enemy soldiers, but upon . . . civilians, cities, farms, animals, the landscape itself.” Over ten years later in 2012, the leading journal in the field—Civil War History—published a special issue titled “The Nature of War” which explored the environment’s dynamic role in the conflict. In the issue, Lisa M. Brady notes with optimism the growing trend toward environmental histories of the Civil War and calls for an even more thorough examination of the conflict from an environmental perspective. Brady’s call has been answered. Megan Kate Nelson, Jim Downs, Yael Sternhell, Kathryn Shively Meier, and Brady herself have published work exploring the environment’s impact on military campaigns and the home front. In a 2014 essay in The New York Time’s “Disunion” blog, Tim Widmer illuminates the extent to which both scholarly and popular interest has turned to the Civil War’s environmental impact. Echoing leading scholarship and reflecting Jack Temple Kirby’s original contention, Widmer posits that the war quickly “became total . . . a war upon the civilians and the countryside as well as upon the opposing forces.” Indeed, the ubiquity of the built and natural environment in influencing nearly every aspect of the Civil War has finally begun to emerge from the shadows. To mark this much needed turn toward an environmental-centered Civil War history, Brian Allen Drake’s edited book, The Blue, the Gray, and the Green: Toward an Environmental History of the Civil War, features an innovative collection of essays by top Civil War and environmental historians that explore a remarkable variety of environmental influences on the Civil War. Just as it has become almost cliché to note the remarkable amount of work published on the Civil War, reinterpreting the war through an environmental lens has provided a fresh and compelling perspective for conflict.[2]

Disease

Disease was the most influential environmental force to shape the Civil War. It accounted for at least 400,000 deaths during the conflict. Diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, malaria, rheumatic fever, and a variety of other ailments plagued Civil War armies and the civilians with whom the armies came in contact. Diet related diseases—most notably scurvy—reflected the generally poor nutrition among the armies. Sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhea and syphilis further impaired soldier health. The topic has been well-covered in Essential Civil War Curriculum. For a detailed examination, see Bonnie Brice Dorwart’s essay “Disease in the Civil War” and accompanying resources.[3]

Weather

Like disease, weather influenced the course of the conflict at every level. A severe drought struck much of the country in the first years of the war, and extremes in heat and cold affected soldiers and civilians alike in the war-torn South. To be sure, the course of the Civil War was in large part dictated by the vagaries of weather. For a more thorough view of weather’s impact on the Civil War, see Kenneth W. Noe’s essay “Civil War Weather” and accompanying resources in Essential Civil War Curriculum. [4]

Terrain/Topography

As any military historian or tactician understands, victory and defeat in battle and war are often tied to geography and, more specifically, terrain. Terrain was a deciding factor for Confederate victory at Fredericksburg and Union victory at Vicksburg. It helped stop Union Major General George Brinton McClellan’s Army of the Potomac at the gates of Richmond in 1862, and it exacerbated the intensity, confusion, and carnage at the Wilderness in 1864. Terrain in the Civil War, historian Mark Fiege has argued, represented a “weapon, shield, and prize.”[5]

In the spring of 1862, General McClellan launched a full-scale invasion of Virginia via the same peninsula on which Jamestown had been founded and British Lieutenant General Lord Charles Cornwallis had been defeated. The Union army’s first significant campaign in the Eastern Theater in which they hoped to take Richmond from the east failed for two reasons: poor leadership and an especially harsh natural environment. According to historian Kathryn Shively Meier, the Civil War in Virginia and elsewhere “forced a crisis of interaction between humans and nature.” Union and Confederate soldiers alike, Meier shows, adapted to the harsh environment through self-care and a perceived notion of “seasoning.” However, no amount of seasoning could overcome the same swampy lowlands that had plagued the first Jamestown settlers. An oversized and overly-cautious Union army stumbled time and again as they approached Richmond’s back door, giving the defending Confederates ample time to organize a defense. McClellan’s failure to effectively and quickly negotiate the terrain—and to recognize his clear numerical superiority—extended the war’s length and devastation. The Union Army of the Potomac took refuge near Washington until forced from their slumber into battle at Antietam. Terrain had consistently been a shaping force for both Federals and Confederates, but it would even more directly shape the course of the war by the end of 1862 and early 1863.[6]

Following their humiliating defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862, the Army of the Potomac under Major General Ambrose Burnside faced another enemy—Virginia mud. A steady winter rain drenched the ground along the Rappahannock River as the defeated Yankees tried to get into position to strike again. The rain-soaked landscape had turned into a nearly impassable quagmire. Teams of horses and mules tasked with hauling parts of the pontoon bridge became buried to their shoulders. Union troops fared little better. According to a New York Times reporter who watched the “Mud March,” the beleaguered Yankees “would founder through the mire for a few feet—the gang of Lilliputians with their huge-ribbed Gulliver—and then give up breathless.” The Confederates across the river watched the foundering Federals with amusement, shouting that they “would come over to-morrow and help . . . build the bridge.” The mud took a toll. Hundreds of work animals died from exhaustion in the “hideous medium.” The same “liquid muck” that had caused their death also became their graves. The difficult landscape proved disastrous for morale as well. According to one Massachusetts soldier, “the very men who had fought uncomplainingly a few weeks before . . . had become more incapacitated by the terrible condition of the roads than by a battle.” Union troops, like Burnside, had regained a modicum of morale and desire for revenge following Fredericksburg, but the rain-soaked terrain had sapped it. Crushing defeat at Fredericksburg had become comparable—even preferable—to the frustrating and humiliating mud.[7]

Just as Burnside’s Yankees stalled out in the mud, Union Major General James Gilpatrick Blunt moved south in pursuit of retreating Confederate army in western Arkansas’s mountainous terrain. The Federal route was trying, especially when Blunt’s little army followed the meandering Cove Creek down the southern slope of the mountains. One cavalryman complained, “We crossed [Cove Creek] thirty-seven times to-day. The winter rains have swelled it until it is a river about forty yards in width, and at no ford less in depth than up to the bellies of the horses.” In crossing and re-crossing the swollen, icy stream in late December, those on horses could not help but feel for their infantry comrades who “had to hold their guns at arm’s length above their heads . . . the water being up to their armpits.” Just as much as difficult terrain shaped large armies, battles, and campaigns, it often lay at the very core of the common soldier experience—east and west.[8]

By the spring of 1863, the Army of the Potomac—now led by Major General Joseph Hooker—was once again foiled by Virginia terrain. In what Civil War scholars concur was Lee’s greatest tactical victory, leaders of the severely outnumbered Army of Northern Virginia used their intimate knowledge of the densely forested terrain around the little town of Chancellorsville to their advantage. The terrain, in effect, became the 60,000-man Confederate army’s force multiplier. In May, Hooker’s bumbling 110,000-man Army of the Potomac fell into a defensive engagement in which General Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson divided their force and hit the Federals from multiple angles in a brilliantly coordinated attack. Key to the subsequent victory was the Confederates’ ability to harness the difficult terrain in their favor. At the battle of Chancellorsville, one historian has argued, “roads, river, bluffs, hills, forests, fields, and fences served as tactical objectives and weapons of war.”[9]

Further west, the Mississippi River represented a key point for both Confederate and Union strategists. In early 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant waged a campaign for control of the Mississippi and its tributaries. His efforts culminated with his costly success at Vicksburg in July 1863. The key to Grant’s strategy and victory lay firmly in his control of the terrain. Rivers, swampy lowlands, and other landscapes endemic to the lower Mississippi River Valley both helped and hindered Union and Confederate forces. Grant’s ultimate ability to harness the terrain gave his army the edge.

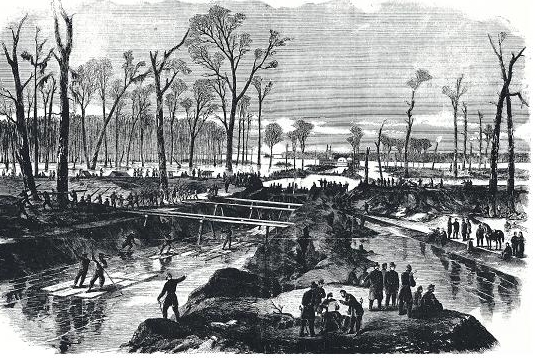

Controlling the natural environment did not come easy, even for an army. In the summer of 1862, as the Union army prepared to assault Vicksburg, Union Brigadier General Thomas R. Williams set out to build a canal in an effort to get around heavy Confederate artillery guarding the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. Intense heat and humidity combined with disease-carrying mosquitos and germ-laden water quickly ravaged the Union ranks. Over 3,000 Union troops and more than 1,000 black laborers nevertheless labored to dig a channel wide and deep enough to skirt the Vicksburg defenses in order to ultimately launch an attack on what Abraham Lincoln had called “the key” to the Confederacy. Heat, moisture, and disease ultimately foiled Williams and, by extension, Grant’s efforts to control the landscape. The Union army had failed to control the terrain, but Grant pressed on.[10]

By the following spring, Grant’s Army of the Tennessee developed a new strategy to take Vicksburg. They crossed the river south of the city, marched toward Jackson, Mississippi, and pushed back west toward Vicksburg. Along the way, the Union army met intense Confederate resistance reinforced by challenging natural and built landscapes. The Federals marched through the ubiquitous wetlands and across brush-laden tangles as they approached the well-defended river city. According to historian Lisa M. Brady, “the rugged and unfamiliar environment posed as great a threat to Grant’s operation as the armed Confederates did.” Just as much as the Union soldiers had fought the natural and built landscape that seemed bent on stopping them, they benefitted enormously from the food and resources collected from the countryside. They consumed vast quantities of livestock and produce and destroyed what they could not take with them.[11]

Once Grant finally made it to the outskirts of Vicksburg, he found Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton’s outnumbered Confederate forces well entrenched in the rugged bluffs and hills surrounding the city. With just over 30,000 soldiers, Pemberton relied heavily on the rugged topography to help thwart the Union army—at least, he hoped, until reinforcements arrived. They never came. From May 18 to July 4, 1863, Vicksburg’s defenders and those civilians trapped in the city had only their environment as an ally. The very topographical defenses that helped the outnumbered Confederates successfully stave off Grant’s initial and intense assaults on the city had doomed its inhabitants to a long and miserable siege during which civilians lived in dugout shelters, or “bombproofs,” in the hillsides and, toward the end of the siege, subsisted on whatever food they could find in the beleaguered town, including rats. All knew at the time that the Union army’s control over the environment—not the Union troops by themselves—had forced the Confederates to capitulate. According to one Confederate chaplain, the Yankees “did not seem to exult much over our fall, for they knew that we surrendered to famine, not to them.” In the end, the Vicksburg campaign reflects the direct and central role topography specifically and the environment more generally played in shaping both the Confederate and Union forces. Both sides benefitted and suffered from the land and, much like the war as a whole, the side that more effectively controlled the environment succeeded.[12]

While large armies attempted to control the natural environment, Confederate guerrillas used rugged terrain to their advantage. The very name Union soldiers attributed to them—“bushwhackers”—reflected their close relationship with the natural topography. Guerrilla bands thrived in difficult terrain. Rugged hills and mountains covered with dense foliage and marked by ravines proved especially useful for irregular operations against the more predictable Union armies and their supply lines. The Ozark Plateau and the Appalachian Mountains served hot spots for irregular activity. As historian Brian D. McKnight has shown, the mountainous region where Virginia and Kentucky meet fostered a kind of conflict in which the “primacy of geography did much to dictate the course of the war.” There, as in the Ozarks, difficult topography funneled regular forces into certain areas while the regions off the major thoroughfares became more apt to suffer “malicious mischief.” Tree-lined waterways and dense wetlands also proved especially effective guerrilla haunts. Guerrillas used dense foliage along major rivers to surprise Union transportation craft, and they hid with great efficacy in the swamps and wetlands in Louisiana and Arkansas. Some Confederate guerrillas—most notably William Clarke Quantrill and his band—fled Missouri and Arkansas and rode as far south as Texas in the winter due to harsher conditions and a general lack of leaves to hide behind. Others remained. Indeed, in the winter of 1863, the Union garrison at Fayetteville burned much of the surrounding landscape in an effort to dispossess the local Confederate guerrillas of their hiding place. Union guerrilla chasers knew well the role vegetation played in helping guerrillas ply their trade. This version of deforestation reflected not only Yankee frustration but also the central role played by the natural environment. [13]

Control over terrain ultimately decided the war. The “hard” or “total” war waged by large Union armies in the last year of the conflict was focused intently on the Confederacy’s ability to make and support war. As Lisa M. Brady has shown, Union major generals Philip Henry Sheridan and William Tecumseh Sherman struck at the “agro-ecological” lifeblood of the Confederacy. The war had become far more than back-and-forth attempts to destroy the other side’s army. It had evolved into a war to destroy the Confederacy’s built environment. For Sheridan, this became a key objective in the oft-contested Shenandoah Valley in 1864. As General Ulysses S. Grant pushed Lee’s beleaguered army toward Richmond, Sheridan made war on the lifeblood of the valley, rendering the “agricultural landscape fundamentally altered.” Further south, Sherman’s objective was simple: control and, where possible, destroy the Confederacy’s built landscape. The Confederacy could not recover from the environmental onslaught.[14]

Food/Agriculture

The course of the Civil War also hinged on food. Historian Ted Steinberg has called the conflict “The Great Food Fight,” and his description is not far off the mark. Armies relied on enormous amounts of food each day simply to survive, not to mention wage war. Supply-laden wagon trains often stretched for miles behind marching armies the largest of which depended on over 600 tons of supplies per day and over 30,000 draft animals. These mobile cities of animals and men needed sustenance. Food, in essence, fueled the armies and the war.[15]

A steady food supply not only staved off defeat, but it became a key factor that directly influenced campaigns. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland in 1862 for several reasons, but food supplies had a lot to do with it. Virginia farmers had suffered for over a year, and a late summer campaign into Union territory would relieve pressure on their farms at harvest. It would also enable Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to commandeer much needed food and supplies from Yankee citizens rather than further sapping the already taxed Virginians. Drought and territory loss had led to significant food shortages and desperate Confederate quartermasters. Hog production had declined considerably due to the loss of much of Tennessee, and a poor corn crop in tandem with transportation issues together meant that Lee’s army must attempt to subsist on Yankee fare. Instead, because of the brief and largely unsuccessful Antietam Campaign, the already beleaguered Confederates mostly relied on ubiquitous green corn and apples.[16]

Dietary demands did not end on the battlefield. Thousands of civilians defended their livestock and crops from soldiers and guerrillas. Micro-battles over environmental control occurred at pigpens and corncribs across the South. Women and children fought their own battles to preserve their livelihood (and lives) by protecting their food stores and livestock. In Osceola, Missouri, in 1861, Jim Lane’s Union “Red Legs” torched the town and confiscated all the livestock they could find, but they missed one woman’s hogs. She risked everything to rescue her squealing pigs from a pen connected to a burning barn. Another woman from Arkansas faced down a group of Union troops who demanded her hog. The Federals killed the pig, but she refused to allow them to take the carcass by positioning herself between them and the pig. The frustrated Yankees exploded with anger, but they left empty handed. Countless similar stories occurred throughout the South. When not fighting each other, Union and Confederate soldiers and irregulars waged a different kind of war against civilians, one often centered on livestock and crops.[17]

Such an increasingly agriculture-centered conflict led to unintended consequences. Livestock not killed or stolen escaped into the new war-induced wilderness. The Civil War turned countless thousands of cows and pigs feral. This occurred throughout the South but was especially pronounced further west in Arkansas and Missouri. A day of intense fighting at Prairie Grove on December 7, 1862, left hundreds of dead and wounded soldiers on the field. That night, as the Confederate army retreated south through the Ozarks, dozens of feral hogs swarmed the battlefield and tore at the dead and wounded. According to one horrified Union soldier, a Federal officer who had died in the fight had his clothes ripped off by swine who then had eaten “half of his face off.” Yankee troops killed as many of the offending Arkansas hogs as they found. They then built pens in which to stack the dead until burial in an effort to keep the ravenous pigs out. Domestic pigs freed by war had become an organic, if horrifying, part of the war.[18]

Elsewhere, soldiers tried to take advantage of the increasing population of feral livestock and unattended perennial crops. Irregular war in the western reaches of Arkansas and Missouri was underscored by the need for regular foraging, and Union soldiers knew well the potential benefits that the countryside offered. Soldiers from the 12th Kansas, marching through southwest Missouri from Fort Scott to Fort Smith, encountered an area nearly devoid of human life but brimming with food. Feral hogs easily adapted to the desolate environment and perennial crops, especially apples, needed little human labor. In fall and early winter, orchards provided an ideal food, and discovering such natural bounties made for diary-worthy news. “Come across a fine lot of hogs which we more than went for,” recorded Union private Henry A. Strong. Two days later, Strong and his fellow soldiers “got two wagon loads of apples at a Rebel’s . . . . All in gay spirits.” Again, three days later, they ventured “into the country after some eatables. Got plenty of apples and fresh pork.”[19]

This perpetual struggle for control of food eventually shattered southern agriculture and the built southern landscape. By 1863, British visitor Lieutenant Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle, accompanying the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, noted the desolate Virginia countryside that had been shattered by two years of war. The Shenandoah Valley, he said, had been “completely cleaned out.” Fremantle noted where there had once been thriving farms, the landscape was “almost uncultivated, and no animals are grazing where there used to be hundreds.” Roving cities of soldiers had emptied the land of food and supplies. Civilians were forced to scrape by with very little. Neither corn, horses, nor any other vestige of agricultural civilization seemed to remain in the war-torn region.[20]

Food shortages plagued urban areas as well. In April 1863, citizens—mostly women—exploded into a riot in Richmond, Virginia. Just before the “bread riot” commenced, one girl noted, “We are starving. As soon as enough of us get together, we are going to the bakeries and each of us will take a loaf of bread.” An overly taxed food supply in tandem with harsh weather and transportation issues led nearly a thousand women and children to demand food. They took by force what had not been handed over. Similar riots occurred in other cities throughout the South, further reflecting the war’s delicate and dangerous association with food.[21]

Such localized total war had evolved into a conflict that hinged on food. A Union captain reported in 1864 that northwest Arkansas was a wasteland. One of the few rural homes still standing had been staunchly defended by a group of women and children who, the Federal officer noted, had hidden corn beneath the floor. Corn stores meant life or death for the impoverished locals. In a rare sign of compassion in an increasingly malevolent war, the Union troops moved on.[22]

On a larger scale, the Union army declared war on livestock in the last year of the war. While countless civilians across the South faced down bands Union and Confederate soldiers and guerrillas in often vain attempts to protect their agricultural livelihood, larger armies wreaked havoc on Confederate food agriculture, especially livestock. In 1864, Union General Philip Sheridan’s army destroyed or captured almost 40,000 cattle, sheep, and hogs in the Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan and other Union commanders knew that victory in war meant destroying not just the Confederate army, but the southern civilians’ will and ability to carry on. As a result, the conflict in Virginia and elsewhere had become largely fought with and for livestock. This had a devastating affect not only on the Confederate war effort, but also on future livestock numbers. According to historian Jack Temple Kirby, hogs—once a ubiquitous resource in the South—never recovered to their pre-war population levels. [23]

Conclusion

Disease, weather, terrain, food, and other environmental factors shaped the Civil War more than any battle or campaign. Control over the natural and built environment ultimately led to Union victory. As a consequence, the Civil War became what Mark Fiege has called an “organic conflict.” As much as anything else, the conflict was a “biological struggle.” Scholars have long recognized individual environmental influences on the conflict, but these environmental forces have typically been relegated to the periphery of the collective Civil War narrative. Thankfully, historians have begun to place the environment at the forefront in an effort to better understand the dynamic and complex environmental forces that tied the natural and built environment to the course and outcome of the conflict. At the least, scholars have largely come to recognize the merits of viewing the Civil War through an environmental lens.[24]

- [1] For the best examination of the environment’s influence on the overall war effort, see Mark Fiege, This Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 199-227.

- [2] Jack Temple Kirby, “The American Civil War: An Environmental View,” Nature Transformed: The Environment in American History (Durham, N.C.: National Humanities Center, 2001), http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntuseland/essays/amcward.htm accessed March 25, 2015; Lisa M. Brady, “From Battlefield to Fertile Ground: The Development of Civil War Environmental History,” Civil War History 58, no. 3 (September 2012): 320-321; Lisa M. Brady, War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes during the American Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), Jim Downs, Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), Yael A. Sternhell, Routes of War: The World of Movement in the Confederate South (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), Kathryn Shively Meier, Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Ted Widmer, “The Civil War’s Environmental Impact,” “Disunion,” The New York Times, November 15, 2014; Brian Allen Drake, ed., The Blue, the Gray, and the Green: Toward an Environmental History of the Civil War (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

- [3] Bonnie Brice Dorwart, “Disease in the Civil War,” Essential Civil War Curriculum (November 2012), http://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/, accessed March 25, 2015. Also see Margaret Humphreys, Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013) and Andrew McIlwaine Bell, Mosquito Soldiers: Yellow Fever, Malaria, and the Course of the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010).

- [4] Kenneth W. Noe, “Civil War Weather,” Essential Civil War Curriculum (MONTH YEAR), http://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/, accessed March 25, 2015. See also Meier, Nature’s Civil War, , Kathryn Shively Meier, “Weather During the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, May 2013), www.encyclopediavirginia.org/weather_during_the_civil_war, accessed March 25, 2015, Robert K. Krick, Civil War Weather in Virginia (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007), and Harold A. Winters, et al., Battling Elements: Weather and Terrain in the Conduct of War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

- [5] Fiege, Republic of Nature, 210.

- [6] Meier, Nature’s Civil War, 9.

- [7] Frank Moore, ed., The Rebellion Record, A Diary of American Events: With Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, etc., 12 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1863), 6:399; Charles E. Davis, Jr., Three Years in the Army: The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers from July 16, 1861, to August 1, 1864 (Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1894), 191. Also see, Kathryn Shively Meier, “Weather During the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, May 2013), www.encyclopediavirginia.org/weather_during_the_civil_war, accessed March 25, 2015.

- [8] Albert R. Greene, “Campaigning in the Army of the Frontier,” Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1915-1918 (Topeka, 1918), 14:301-302.

- [9] Fiege, This Republic of Nature, 210.

- [10] For a thorough analysis of the Union attempts to build a series of canals around Vicksburg, see especially Brady, War Upon the Land, 28-41. Also see Terry L. Jones, “The Canal to Nowhere,” Disunion Blog, New York Times, January 18, 2013.

- [11] Brady, War Upon the Land, 53-55 (quote on p. 53).

- [12] “Letters Home: William Lovelace Foster,” Vicksburg National Military Park, National Park Service, accessed October 31, 2014, http://www.nps.gov/vick/forteachers/letters-home-foster.htm, accessed March 25, 2015. Also see Steinberg, Down to Earth, 96. For the best treatment of the Vicksburg campaign, see William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel, Vicksburg is the Key The Struggle for the Mississippi River (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003).

- [13] Brian D. McKnight, Contested Borderland: The Civil War in Appalachian Kentucky and Virginia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky), 2; Matthew M. Stith, “‘The Deplorable Condition of the Country’: Nature, Society, and War on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier,” Civil War History 58 no. 3 (September 2012):345.

- [14] Brady, Down to Earth, 73.

- [15] Ted Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 89. Also see James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 325.

- [16] Keith S .Bohannon, “Dirty, Ragged, and Ill-Provided For: Confederate Logistical Problems in the 1862 Maryland Campaign and Their Solutions,” in Gary W. Gallagher, ed., The Antietam Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 102-103. Also see Steinberg, Down to Earth, 93.

- [17] Stith, ‘The Deplorable Condition of the Country’, 328-329; Robert W. Mecklin, The Mecklin Letters, edited by W. J. Lemke (Fayetteville: Washington County Historical Society, 1955), 25.

- [18] Quoted in William L. Shea, Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 256.

- [19] Tom Wing, ed., “A Rough Introduction to This Sunny Land”: The Civil War Diary of Private Henry A. Strong, Co. K, Twelfth Kansas Infantry (Little Rock: Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 2006), 14-15.

- [20] Arthur James Lyon Fremantle, Three Months in the Southern States: April-June 1863 (1863; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 222-5. Also see Gary W. Gallagher, The Confederate Home Front: How Popular Will, Nationalism, and Military Strategy Could Not Stave Off Defeat (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 161-2.

- [21] Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, Reminiscences of Peace and War (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1904), 238; Michael Fellman, Lesley J. Gordon, and Daniel E. Sutherland, This Terrible War: The Civil War and Its Aftermath (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2003), 240.

- [22] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 34, part 2, p. 605.

- [23] Jack Temple Kirby, Mockingbird Song: Ecological Landscapes of the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 128.

- [24] Fiege, This Republic of Nature, 221.

If you can read only one book:

Drake, Brian Allen ed. The Blue, the Gray, and the Green: Toward an Environmental History of the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015.

Books:

Bell, Andrew McIlwaine. Mosquito Soldiers: Yellow Fever, Malaria, and the Course of the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010.

Brady, Lisa M. War Upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes during the American Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

Downs, Jim. Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Fiege, Mark. “The Nature of Gettysburg: EnvironmentalHistory and the Civil War” chap. 5 in The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Krick, Robert K. Civil War Weather in Virginia. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Meier, Kathryn Shively. Natures Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Nelson, Megan Kate. Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

Steinberg, Ted. “The Great Food Fight” chap. 6 in Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in the American History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Sternhell, Yael A. Routes of War: The World of Movement in the Confederate South. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Stith, Matthew M. Extreme Civil War: Guerrilla Warfare, Environment, and Race on the Western Trans-Mississippi Frontier during the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2016.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.