Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign

by Kendall D. Gott

Grant's 1862 Campaign to capture the Tennessee and Cumberland River forts and thereby secure Nashville and most of Tennessee for the Union.

The campaign on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers was the first significant victory for the Union during the American Civil War. After a string of Union defeats in 1861, the capture of Fort Donelson was decisive and devastating for the South. In one campaign the Confederate defenses in the West were shattered, necessitating the abandonment of most of Tennessee and the state capital of Nashville. Union gunboats were then able to ascend the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers to wreak havoc deep into the Confederate heartland. The disasters at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson began the slow and bloody dismemberment and ultimate defeat of the Confederate States of America.

The Union was not alone in recognizing the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers as good invasion routes into the Confederacy. The South realized that the loss of the Tennessee River would allow the enemy river fleet to isolate western Tennessee from the east and penetrate virtually all the way to Florence, Alabama. Any such move would threaten the Confederate fortress guarding the Mississippi River at Columbus, Kentucky, the city of Memphis, and the vital rail center at Corinth, Mississippi. Loss of the Cumberland River would spell doom for the key supply and manufacturing center of Nashville and cut off the Confederate Army at Bowling Green. Union control of the Mississippi would effectively split the South in two, and reopen river traffic to the Midwest, linking it to the profitable European markets. Therefore, the defense of the great Southern rivers was key to the ultimate survival of the Confederacy.

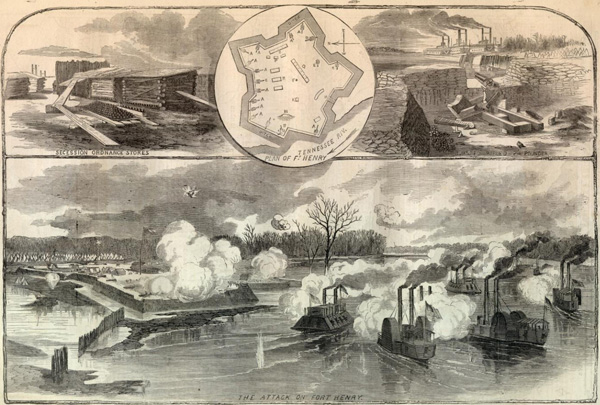

When Tennessee seceded from the Union, it raised a provisional army for its defense and Governor Isham Green Harris ordered likely spots along the rivers fortified and blocked as soon as possible. Political considerations dictated that the forts be located in Tennessee and as close to the border as possible. A surveying team was formed and sent to select defensible ground dominating the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. The team of engineers first looked at the high ridges and deep hollows along the Cumberland River. In mid-May, Fort Donelson was laid out on the west bank of the river not far below the town of Dover. The engineers then made their way to the Tennessee River and after much discussion Kirkman’s Old Landing was decided upon, in spite of the fact that it was on low ground dominated by hills across the river. Some members of the team strongly objected but construction began in June on Fort Henry. Many would regret this decision, and Fort Henry’s poor location would be a key factor in the coming campaign.

Work on both forts in 1861 was slow due to a low priority given to them. There were constant and chronic shortages of troops, labor, and heavy guns. Fort Henry was a particularly weak position necessitating a supplemental fieldwork to protect it. Located across the river, Fort Heiman was designed to prevent an enemy from occupying the hill and enfilading Fort Henry, but very little work was done on the site. What Fort Henry and Fort Donelson needed was firm leadership and unity of control over the defensive preparations. General Albert Sydney Johnston delegated the task of preparing defenses along the Tennessee and Cumberland to Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, who assumed command of both forts on November 17th.

While the Confederates raised armies and prepared their defenses, the North prepared to invade the Deep South. Major General Henry Wager Halleck was under a lot of pressure from President Lincoln to begin an offensive, and General Ulysses S. (Hiram Ulysses) Grant alone was reporting as ready to move. Given the go ahead, Grant moved south, shuttling his two divisions in the available transports up the Tennessee beginning on February 2, 1862. In four days he had the bulk of his forces at “Camp Halleck” just four miles north of Fort Henry. The plan was to bombard the fort into submission with the new ironclad gunboats and use his army to block any retreating Confederates from escaping eastward to Fort Donelson. Grant was confident of success since reconnaissance revealed the general weakness of the fort. Also, the winter rains had raised the river several feet bringing the fort’s guns nearly to water level thus negating any advantage in height.

Upstream, General Tilghman watched the rising waters of the Tennessee and the Union preparations. The situation was grim. Facing the floodwaters and heavy naval cannon General Tilghman ordered the abandonment of Fort Heiman and prepared to evacuate Fort Henry. About 90 volunteers manned the river batteries to buy time for his army to retreat and inflict as much damage on the Union fleet as possible. Tilghman planned to remain with the gunners just long enough to assess the Federal assault and rejoin his command of some 2,500 men in their escape to Fort Donelson.

On February 6 Grant’s gunboats and the two infantry divisions left Camp Halleck at 11:00 a.m., and in just over two hours the gunboats pounded Fort Henry into submission. Led by General Tilghman, the gun crews made a valiant defense in spite of the floodwaters of the Tennessee actually entering the fort proper. Yet the vaunted ironclads suffered too, having one disabled and the remainder badly damaged. Grant’s infantry was slowed by the rain-soaked roads and failed to block the retreating Confederates’ path. Caught up in the excitement of battle, General Tilghman did not leave the fort as planned, but was captured with the small garrison. The Fort Henry evacuees arrived at Fort Donelson the next day with only their arms and accoutrements, having left their camp equipage behind. Without a commanding general the combined garrison at Fort Donelson languished in place and did not appreciably improve the defenses.

The fall of Fort Henry left Johnston in a desperate situation. The Confederate line of defense in the West was broken and Grant was preparing to move on Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. If it fell, the capital at Nashville could not be defended and any Confederate forces north of the river would be cut off and trapped. To prevent this catastrophe Johnston ordered the evacuation of Bowling Green and the reinforcement of Fort Donelson.

To Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow there was no doubt that the key to defending the Cumberland River was Fort Donelson, and he did what he could to improve the defenses. Stationed in Clarksville, Pillow was chiefly responsible for the vast amount of supplies previously sent to the fort, and as regiments from Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner’s division and Brigadier General John Buchanan Floyd’s brigade arrived he sent them on to Fort Donelson. Pillow received orders directly from Johnston to take command of Fort Donelson and arrived there on February 9. He inspected the defenses and was impressed with the location of the water batteries. Pillow did find that although the lighter guns were mounted, a heavy Columbiad and a rifled 6.5 inch were not. His orders set the work in motion to correct this deficiency. The landward defenses, however, were entirely inadequate. Pillow ordered the digging of earthworks as a priority effort and sent teams forward to fell trees to clear fields of fire and form a sort of crude abatis. Although most of the ground was covered by thick underbrush that made infantry movement difficult anyway, branches from the overlapping trees were cut and sharpened to hamper an assault. The semicircular earthworks were anchored to the north on Hickman Creek and to the south on Lick Creek. At this time both streams were flooded and were serious obstacles.

Within a few days Pillow felt better about the state of affairs at Fort Donelson. The defenses were at least organized if not fully prepared. But that was changing too as the men continued to construct earthworks and obstacles. Morale was improving, the supply system was functioning fairly well, and the reinforcements from Buckner’s and Floyd’s commands were arriving. One of the welcome additions to the garrison was the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest. There had been few cavalrymen available up to this point and they would be used to acquire additional information on Grant’s movements. By February 10 there were approximately 11,000 men in the fort.

General Buckner had arrived at Clarksville and met with Floyd to discuss a strategy he had formulated. Buckner proposed that the remaining troops at Clarksville and his original command, which was already at Fort Donelson, be brought back to Cumberland City, which was about halfway between the fort and Clarksville. Pillow’s mission would be to fix Grant and hold Fort Donelson as long as possible with only the original garrison and a few additional units. Buckner argued that Cumberland City, not Fort Donelson, was where they should make a stand. He argued that placing this force at Cumberland City would allow it to operate against Grant’s line of logistics without fear of being cut off by the gunboats or isolated by land forces as those at Fort Donelson. In Buckner’s plan, Pillow and Fort Donelson were expendable.

Floyd approved the plan, but there had been no defensive preparations made at Cumberland City at all, and the small force envisioned for Fort Donelson would be completely inadequate for its task of fixing Grant. Buckner went to Fort Donelson to supervise the removal of Floyd’s brigade of Virginians and his own small division from Fort Donelson to Cumberland City. Pillow wanted no part of it and forbade the removal of any troops until he could discuss the matter with Floyd. The next morning, he boarded a steamboat and traveled the fifteen miles to Cumberland City to persuade Floyd to change his mind.

John B. Floyd was unsure of the strategy his superior Albert Sidney Johnston wanted to employ. Floyd had telegraphed him days earlier asking for guidance and for Johnston to pay a visit to this threatened sector. Instead of producing guidance or a visit, Floyd’s telegrams only irritated Johnston, who believed the brigadier was vacillating. Floyd was not a professional soldier and was certainly in over his head. Additionally, his chief subordinates, Pillow and Buckner, despised each other from incidents dating back almost fifteen years. As a result of all of this the Confederate senior command was not cohesive.

General Grant was ready to leave Fort Henry on February 12 and move on Fort Donelson. The gunboats were not yet repaired, but leaving now would allow him to completely invest the fort before their arrival and prevent a repeat of the Fort Henry operation. Grant’s army began the twelve-mile march towards its objective along the two narrow and muddy roads heading east, boldly moving in the face of an enemy it knew little about. The engineers assessed the earthworks of Fort Donelson as being poorly built, but no one had any idea of just how many Confederate soldiers were in the outer works. Captured Confederates revealed that there were up to 25,000 men in the fort, although there were actually only about 20,000 by this time.

Grant’s battle plan was again a simple one. The gunboats in the river would destroy the water batteries, and the artillery on land would bombard the fort from the landward side. Surrender should follow quickly, just like Fort Henry. The Union forces maneuvered into position as a division under Brigadier General John Alexander McClernand formed a line on the right flank facing the town of Dover, Brigadier General Lewis “Lew” Wallace took the center, and another Union division under Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith took the left flank facing the water batteries. Grant later inspected his lines and concluded that they were thin in places, particularly on the extended right wing.

Grant hated to be idle, and adhering to the plan meant waiting on the gunboats to come up the Cumberland River after being repaired. Waiting also allowed the Confederates more time to strengthen their defenses. On the morning of February 13, he ordered his forces forward to probe the Confederate defenses and the lone gunboat present, the USS Carondelet, to challenge the water batteries. The results were not good for the Federals. The ironclad was damaged after trading shots with the Confederate water batteries. Morrison’s brigade launched three frontal assaults through the tangled brush and deep ravines and was driven back with heavy losses. A brigade of Smith’s division seized a hilltop in its assigned sector, but it too was driven back. As evening came all of the Union troops began to realize that Fort Donelson was going to be tough fight.

That evening it began to rain, which turned into a driving blizzard as the temperatures plunged. The opposing lines were too close to risk warming fires. Most Federals left behind their overcoats and blankets in piles to facilitate a rapid march. Many Confederates did not have theirs either in the haste to reinforce the garrison. By morning they were all a miserable lot.

The Confederate brigadiers met in the early hours of February 14 to decide what to do. They were a diverse assortment. Floyd was essentially a politician in uniform. Pillow was arrogant, egocentric, insubordinate, and dominantly assertive. Buckner was junior, but the most professionally competent. Scouting reports suggested that the Federals totaled some 40,000 men, with possibly more on the way. These inflated numbers prompted the decision to break out of their predicament and escape to Nashville.

Pillow was designated to lead the assault, and Buckner would lead the rear guard. Couriers were sent to alert the various units, which slowly began their movements to their start points. Hours were spent getting regiments into assault position, but for reasons unknown the word to commence the attack never came. As more hours passed the Confederates stacked arms and built fires to keep warm. By mid-afternoon the chance to launch the attack had passed. There were only three to four hours of daylight left, and there were developments on the river. Pillow eventually passed word to the troops to quietly return to the trenches. Back at the headquarters in Dover, Floyd lost his composure when he found out about the order but it was too late. The Confederates lost a good chance to withdraw from the fort fairly unmolested.

The development on the river was the appearance of the dreaded gunboat flotilla consisting of four ironclads and two wooden gunboats. Their commander, Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote, was not as confident of success as he had been at Fort Henry. He had witnessed first-hand what a heavy gun could do to his lightly armored fleet, and here his boats were vulnerable to plunging fire from the guns above the river. At noon the ironclad fleet moved within range of the Confederate batteries and continued to within 400 yards of the fort. The short range improved the poor Yankee marksmanship, but added to the effectiveness of the southern guns. All four ironclads were severely damaged and Foote was wounded before withdrawing. The strategy used at Fort Henry did not work, and General Grant settled down for a siege.

The morale in the Confederate trenches was high, but it was not the same at the command level. That evening the Confederate commanders met in Dover for a council of war. Floyd was apparently convinced that Grant was reluctant to attack by land but could be reinforced over time to overwhelming strength. He also believed Grant had 40,000 men or more moving to surround the fort at that time. In allowing Grant to completely invest the fortress, it was time for the Confederates to either break out or endure a siege. Floyd argued that the fort would not stand a prolonged siege and called for a breakout. If he could not hold the fort he intended to at least save the little army.

With the arrival of General Floyd, Pillow had assumed command of the left wing. When given the chance to speak, Pillow laid out his views. His scouts reported that McClernand’s division was astride both the Forge and Wynn’s Ferry roads leading south out of Dover. He believed that the Federals were arrayed in three distinct “encampments” as opposed to a continuous line. Pillow also thought these encampments were separated by thick tangles of brush preventing the movement of large bodies of troops. He proposed that Confederates hit the Union right flank and roll it back. When that happened, Buckner would attack and catch the enemy in the flank and rear. Grant would then be pinned against the river.

Buckner next had a chance to speak and proposed a modification of Pillow’s plan. Pillow would attack as planned, but Buckner’s division would play a more active role. It would eliminate the Union artillery covering the Wynn’s Ferry Road, thus reducing the load for Pillow and striking the enemy at a more vital point. During the withdrawal phase Buckner would then move in to protect the flank and rear as Pillow and the garrison escaped to the south. Pillow agreed to Buckner’s changes and Floyd authorized the plan. The Confederates would attack at dawn. With good preparations and timing the chances seemed good for success.

The council of war ended about 1:00 a.m. on February 15 and every officer left with a different impression of what was to transpire. Pillow believed that his troops would return to their trenches after a victory so complete that they could retrieve their equipment at leisure. Buckner thought no one would return to the trenches after commencement of the battle. Thus Buckner’s units were to go into combat encumbered by their equipment and haversacks full of three days’ rations. Some brigade commanders returned to their units and failed to give detailed instructions to their subordinate regiments as to their role in the attack. One brigade sent word only to be ready to move at an instant’s notice in the morning. Time was running short, for the attack was scheduled for 5:00 a.m., and the brigades were to be on line by 4:30 a.m.

Frozen by the miserable weather, the Union troops were just rousing and lining up for breakfast when the assault struck. Although caught by surprise and disorganized, the Federals repulsed the first wave of the attack. Both sides then retired a short distance to reorganize. Forrest dismounted his regiment of cavalry, and Pillow rode through his command urging the men to the fight. The attack soon resumed, and while the Union right held briefly, it fell back and then disintegrated when simultaneously flanked by Forrest’s troopers and hit by the weight of a frontal infantry attack. Running short of ammunition, the survivors of McClernand’s division withdrew onto the Union center. Survivors of McClernand’s division streamed through the line of General Lew Wallace’s division. Sensing disaster, on his own initiative Wallace shifted a brigade to the right to support McClernand’s defense. It was a critical move that saved Grant’s army from total defeat.

On the right wing, Buckner positioned his forces according to plan and was ready to begin the assault to support Pillow. However, Buckner did not begin his assault as agreed the previous evening. Instead he deployed his regiments in defense and brought up two artillery batteries for the purpose of counter-battery fire. Noticing the quiet off to the right, Pillow rode over to Buckner’s command and found his men still in waiting in the trenches. Pillow located Buckner, and heated discussion ensued. General Buckner explained the delay by noting that he had just conducted a probing attack and was bringing up artillery to silence a Union battery. By now though the Federal line had been pushed back and the intended assault point was irrelevant. So Pillow revised the attack plan and instructed Buckner to attack up Erin Hollow, using it for cover and to maneuver additional forces into the flank and rear of the Federal position. The subsequent attack proved successful in pushing back the Union line yet again.

By 12:30 p.m. the door to freedom for the Confederates was open and it was opening wider. Holding the Union center was Lew Wallace’s division and the remnants of McClernand’s, which were desperately short of ammunition and with unit cohesion gone. For all this time General Grant had been away conferring with Foote where the gunboats anchored some miles away. The Federals were battered, shaken, and in need of General Grant to return to decide the next move.

In spite of the frictions in command the Confederates had achieved their goal so far. It was an achievement worthy of the highest praise for Southern arms. Although miserably armed and ill trained, the Confederate soldiers had pushed their counterparts back some four hundred yards through rugged and timbered terrain. The Union right flank was forced back and all that was left of the plan was to extract the garrison.

At this moment General Pillow made a fateful decision. Acting on his own, without consulting Floyd or Buckner, Pillow ordered his men back to their original lines. Buckner watched the retrograde movement of the Confederate left wing in disbelief and rode to confront the Tennessee general. Floyd was sent for and after a heated discussion with Pillow, he let the order stand. Pillow explained that his men were worn out over the day of fighting, out of ammunition, and bitterly cold. They had not brought their knapsacks as Buckner’s men had, and so they were not ready to begin a march to Nashville.

Pillow may also have thought the day’s victory was complete enough to allow an escape at leisure. The Confederates had inflicted over 2,000 casualties and routed four enemy brigades. Both he and Forrest thought that the Federals were too shaken to reinvest the fort quickly. In any case, another opportunity to evacuate the fort had arrived, and it was early enough in the day to do it. Pillow thought it could wait until morning, giving his men a chance to collect the wounded, their equipment, and rations. Unfortunately, the men went all the way back to the trenches without leaving an adequate screening force to keep the escape route to the south open.

About this time General Grant arrived on the battlefield and took stock of the situation. On the Confederate left, he surmised that the trenches there were thinly manned and ordered an assault there. An attack against Buckner’s old positions by General C.F. Smith’s division gained sections of the outer works, but approaching nightfall halted any further advance by the Federals. Feeble counterattacks by General Buckner failed to dislodge the Union troops, leaving them in their advanced positions that endangered the water batteries and the interior of the fort. In McClernand’s old sector, Wallace’s division retook most of the lost ground and positioned itself to assault the line in the morning. As the day ended, an escape route was still open, but the Confederates showed no intention of using it.

Instead, Generals Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner gathered once again in Dover to discuss their options. Pillow and Buckner joined in a heated discussion about the conduct of the battle. Buckner maintained that the object of the operation was attained when the road south was open and that the army should have made good its escape. Pillow maintained the agreement was to return to the camps to retrieve their equipment and withdraw under cover of night. He also proposed that it be now done while there was still a chance to do so.

Scouts reported that the waters of Lick Creek were three feet deep or more and the surgeons felt that crossing the icy waters would result in a high death rate for the infantry. There were other reports too that the Federals had blocked the roads leading south. Forrest was summoned and was adamant in his opinion that the roads were clear of the enemy. He had as late as 9:30 p.m. received word from his cavalry scouts that the way to Nashville was open. Floyd and Buckner still believed the road was blocked and nothing Forrest could say would persuade them otherwise.

Then occurred one of the most historic and amazing examples of the collapse of a command in the annals of American warfare. Floyd, the former secretary of war, had no intention of staying around for the surrender. Buckner chided him and said that if he were in command that he would share the fate of the army in accordance with regulations. Taking that as volunteering for the job, Floyd then passed the command to Pillow who immediately passed it on to Buckner. Buckner sent for a bugler and writing materials and began the process of surrender.

In the morning, Floyd hastily loaded his brigade on two steamboats and escaped to Clarksville. Unfortunately he abandoned a regiment at the landing at the rumor of approaching enemy gunboats. General Pillow crossed the Cumberland with his staff using an old scow. Meanwhile, a battle-hardened group of cavalrymen under Nathan Bedford Forrest crossed Lick Creek and made its way to freedom. On February 16th, the men of the garrison awoke with high morale and ready to fight again, only to learn of the decision of the previous evening.

There are no accurate numbers of the Confederates at Fort Donelson, but it is generally accepted that there were approximately 21,000 troops within the works. About 1,500 were killed or wounded and on February 16, over 12,000 soldiers of the Fort Donelson garrison surrendered unconditionally to the Union forces. The balance of the forces made their escape with Forrest’s cavalry or simply walked through Union lines during the days of confusion after the surrender.

The fall of the two forts sent waves of shock across the South, and the reaction was comparable to the North’s after the debacle at Bull Run. For the South, the loss of this campaign was not only a tactical disaster, but a strategic one as well. In one stroke the vital city of Nashville and most of Tennessee was lost to the Confederacy forever. Albert Sidney Johnston lost an entire army out of his already thin ranks.

Irony and tragedy for the South followed. In but six short weeks after Fort Donelson’s surrender, Albert Sidney Johnston would die of his wounds at the Battle of Shiloh. It was a desperate attempt by Johnston to destroy Grant’s army before Major General Don Carlos Buell’s could join it. However, Grant was reinforced and many of his troops were now veterans. In the bloodiest fight on the continent up to that time, the raw Confederate troops were at the brink of victory when Johnston was mortally wounded. One can only speculate upon the outcome of that battle had the bulk of the 21,000 soldiers of Fort Donelson been present.

If you can read only one book:

Gott, Kendall D Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2003.

Books:

Bailey, L.J. “Escape from Fort Donelson”, Confederate Veteran, February 1915.

Bearss, Edwin C. “The Fall of Fort Henry”, West Tennessee Historical Society Papers, Volume 17, (1963).

Bearss, Edwin C. “Unconditional Surrender: The Fall of Fort Donelson”, Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Volume XXI, Number’s 1 & 2, (March and June 1962).

Bridges, Robert, ed. Confederate Military History, Wilmington, North Carolina: Broadfoot Publishing Co., 1987.

Catton, Bruce Grant Moves South. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1960.

Churchill, James O. “Wounded at Fort Donelson”, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States – Missouri. St. Louis: Becktold & Co., 1892 Volume I.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Foote, Shelby The Civil War A Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958.

Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1885.

Hamilton, James J. The Battle of Fort Donelson. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1968.

Jobe, James The Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson”, Blue & Gray Magazine, Volume XXVIII, Issue 4, (February 2012).

Knight, James R. The Battle of Fort Donelson: No Terms but Unconditional Surrender. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2011.

Logsdon, David R. Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Fort Donelson. Nashville, Tennessee: Kettle Mills Press, 1998.

Morton M.B. “General Simon Bolivar Buckner Tells the Story of the Fall of Fort Donelson”, Nashville Banner, December 11, 1909.

Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1983.

Tucker, Spencer C. Unconditional Surrender: The Capture of Forts Henry and Donelson. Abilene, Texas: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2001.

United States War Department War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 7.

Vaughan, James Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Fort Donelson, February 13-16, 1862. N.p. 2009.

Vesey, M.L. “Why Fort Donelson was Surrendered”, Confederate Veteran, (October 1929).

Wakelyn, John L. Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1977.

Wallace, Lewis “The Capture of Fort Donelson”, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. New York: The Century Company, 1884-1888, Volume I.

Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861-1865: Organization and Operations. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.