Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

by H. Robert Baker

No issue rankled antebellum Americans more painfully or persistently than the fugitive slave problem. While slaveholders had, since colonial days, pursued their slaves who ran away, this problem was magnified by sectional tensions in the decades that preceded Civil War. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in order to help alleviate that tension, but the law ultimately would have the opposite effect. The roots of the Fugitive Slave Act extended back to the earliest days of the Republic. Its constitutional source was located in Article IV, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which provides that “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 anticipated the difficulties in law enforcement that fugitive reclamation brought. Commissioners were empowered to appoint men to aid in the capture, detention, and rendition of fugitive slaves, and marshals were given the authority of posse comitatus, which allowed them to call upon any bystander to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. The new Fugitive Slave Act occasioned swift condemnation in the North where a torrent violent resistance began. Into this tumoil came the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1854 further inflaming both sides as did a series of highly publicized fugitive slave seizures occurred including Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, Joshua Glover and most famously Anthony Burns in Boston. Secession in 1860 and 1861 did not serve to quell the fugitive slave issue. The border states of Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri still held slaves, and Abraham Lincoln entered office committed to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. Republicans, despite being firmly in control of Congress, failed on several occasions to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act. Finally, in 1864, Congress repealed both the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, and Lincoln signed the repealing legislation. A year later, the Thirteenth Amendment ended forever the problem of fugitive slaves in America.

No issue rankled antebellum Americans more painfully or persistently than the fugitive slave problem. While slaveholders had, since colonial days, pursued their slaves who ran away, this problem was magnified by sectional tensions in the decades that preceded the Civil War. Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in order to help alleviate that tension, but the law ultimately would have the opposite effect.

The roots of the Fugitive Slave Act extended back to the earliest days of the Republic. Its constitutional source was located in Article IV, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which provides that “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”

There were clear commands in this clause, but they were ambiguously stated. The right of the slaveholder to his slave, even when he or she fled to jurisdictions where slavery was not tolerated, was clear. So too was the prohibition on the states that they not free slaves who fled to their jurisdiction. Another clear command was that fugitives “shall be delivered up” to their masters. Left ambiguous, however, was who had the responsibility to deliver up the fugitive. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 clarified this to some degree by creating a private right of action for the slaveholder. By the 1793 act, the slaveholder was entitled to arrest a fugitive him/herself, bring that fugitive before a court or magistrate, and there receive a certificate of removal. Anyone obstructing the slaveholder in his or her claim was liable to the slaveholder in an action of debt.

For five decades, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 existed in tandem with fugitive slave acts and so-called personal liberty laws passed by individual states, both slave and free. [1] This coexistence was not without controversy and differed from state to state. In states where well-organized abolitionist societies contested fugitive slave reclamation, such as Massachusetts, the conflicts were numerous. In Border States, such as Ohio and Pennsylvania, the conflicts could easily turn violent.[2] In virtually every case, they involved legal challenges to the power of both state and the federal government to pass fugitive slave laws.[3]

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), the Supreme Court of the United States considered the conflict of laws created by separate state and federal laws on the same constitutional provision.[4] The Supreme Court unequivocally settled on the notion that the federal government was empowered to pass fugitive slave laws, although the justices disagreed as to whether the states had a concurrent power to pass fugitive slave laws themselves. But no matter. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Prigg v. Pennsylvania settled the question for the nation that Congress had the supreme authority to pass fugitive slave laws.[5]

Thus was the constitutional footing upon which Congress revised the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. But what mattered most was the political setting within which Congress considered the bill. No one doubted that the Union was fragile in 1850, and perhaps on the brink of disunion. Among the grievances cited by southern states was northern non-compliance with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Southerners had long sought a more robust federal law but had been unable to secure ample congressional support. They had brought such bills to the floor of Congress on multiple occasions, and were uniformly rebuffed.

Matters were different, however, in 1850. Necessity drove the free states into a compromising stance. Several southern states were planning a summer meeting in Nashville to discuss, quite openly, the possibility of disunion. While southern demands were numerous and varied, key among them was the complaint that northerners had shirked their constitutional duties. “I fear,” said Senator James Mason of Virginia from the Senate floor on January 28, 1850, “that the legislative bodies of the non-slaveholding States, and the spirit of their people, have inflicted a wound upon the Constitution which will prove itself vulnus immedicabile” (an irreparable injury). He went on to admit that a new national fugitive slave law would be beneficial, but warned that “no law can be carried into effect, unless it is sustained and supported by the loyalty of the people to whom it is directed.”[6]

The bill occasioned a good amount of controversy, although this fact was muted by the bill’s place in a set of compromise measures that would be passed in 1850. None of the northern amendments, which provided procedural protection for alleged fugitives, would be adopted in the final draft. In fact, the bill which Millard Fillmore signed into law on September 18, 1850, was unabashedly proslavery.

The new law authorized judges of U.S. courts to appoint court commissioners who could preside over rendition hearings. This was deemed a necessity by slaveholders who understood that the skeletal U.S. court system, which often times had but one or two courts available in any given state, would not be sufficient to guarantee effective enforcement of the law. The appointment of commissioners would allow for both geographic reach (commissioners could hold office in towns where there was no federal district court) and caseload relief (there was a limit to the number of cases a district or circuit court could take).

The new Fugitive Slave Act added an important procedural protection for slaveholders. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 had given slaveholders the authority to seize fugitives wherever they found them, and the Supreme Court and sanctioned this practice in Prigg v. Pennsylvania. But seizing fugitives without an arrest warrant was dangerous, primarily because abolitionists (white and black) often provided forcible resistance to private arrests. It was dangerous for another reason. If slaveholders seized someone who had a legitimate claim to freedom, then they incurred legal liability. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 sought to remedy this by providing a process for obtaining arrest warrants for fugitive slaves. The process, however, was optional. Slaveholders could still seize their fugitives where they found them, or they could obtain an arrest warrant and employ the power of U.S. law enforcement to arrest and detain fugitive slaves.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 anticipated the difficulties in law enforcement that fugitive reclamation brought. Commissioners were empowered to appoint men to aid in the capture, detention, and rendition of fugitive slaves, and marshals were given the authority of posse comitatus, which allowed them to call upon any bystander to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Slaveholders were given explicit protections. The old Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 had allowed slaveholders to sue anyone who interfered with fugitive slave rendition for $500. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 doubled this amount. It added criminal penalties for anyone who interfered with U.S. officers. It also made the U.S. marshal personally liable to a slaveholder if a fugitive escaped (or was forcibly rescued) from his custody. [7]

Such revisions provided robust protections for slaveholders pursuing property rights. Protections for free blacks wrongfully seized, however, were entirely absent. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 had provided the sketch of a procedure for rendition hearings, which were to be summary (that is, held by a judge or magistrate without the assistance of a jury), and in which the standard of proof for the issuance of a certificate of removal was completely undefined. While this was hardly fair procedure for alleged fugitives, it did allow some discretionary power for judges to consider the possibility that the alleged fugitive was in fact free. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, on the other hand, deliberately excluded the testimony of the alleged fugitive slave and explicitly prevented state authorities from intervening. Practically, this meant that the states could not protect free blacks wrongfully seized on their own soil.

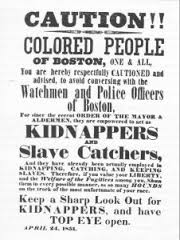

The new Fugitive Slave Act occasioned swift condemnation in the North. Public meetings held in northern cities condemned the Fugitive Slave Act as immoral and unconstitutional. At a meeting in Faneuil Hall in Boston, Charles Francis Adams implored the assembled crowd to seek repeal of the law while noting the “impossibility of inducing our citizens to execute its shameful provisions.” A mass meeting in Minerva New York resolved that the Fugitive Slave Act was not binding and void, and promised “positively to disobey it.”[8]

Such words proved prophetic. While fugitives in several states were arrested and remanded under the new law almost immediately, large crowds formed and menaced slavecatchers and U.S. marshals. The most brazen example of this occurred in Boston, where William and Ellen Craft, two fugitives from Georgia, lived in open defiance of federal law. The Crafts escaped by disguising Ellen Craft as a white planter and having William Craft pose as her manservant. This escape, conducted in plain sight rather than by Underground Railroad, and the Crafts very public leadership roles in the northern antislavery movement made them heroes to abolitionists. On October 25, 1850, warrants for the Crafts’ arrest were issued to the U.S. marshal. The Crafts proved impossible to arrest, and the Boston Vigilance Committee sprang into action. Slavecatchers were harassed legally, arrested on trumped up charges, and threatened with violence. Meanwhile, the Crafts continued to move about freely, more or less with impunity. Ellen Craft left the city for protection, and William Craft armed himself to the teeth, booby-trapped his house, and prepared for violent resistance if necessary. The Vigilance Committee ultimately ferried the Crafts out of the city, and the first attempt to execute the Fugitive Slave Act in Boston proved humiliating to the federal government.[9]

On February 15, 1851, the first successful arrest of a fugitive slave under the new law in Boston occurred. Shadrach Minkins was born a slave in Norfolk, Virginia. In May 1850, he escaped servitude, likely by stowing away on a ship bound for Boston harbor. There he integrated into Boston’s free black community and supported himself by working as a waiter at the Cornhill Coffee House. On February 15, 1851, assistant deputy marshals took hold of Shadrach Minkins in the hallway outside the coffee room and proceeded to take him to the courthouse, only a block away. The sight of a fugitive slave being taken prisoner and herded towards the courthouse instantly became news, and within a short time Shadrach Minkins had a legal defense team and more than one hundred supporters, predominantly from Boston’s black community, to witness his hearing. Minkins’s supporters overwhelmed federal officers and rescued him. And so on the same day that the first successful arrest of a fugitive slave under the new law in Boston occurred, so too did the first fugitive slave rescue.

Shadrach Minkins’ rescue embarrassed the Fillmore administration, and in particular the secretary of state, Daniel Webster. Webster believed firmly that the Union’s survival depended upon the faithful execution of the terms of the Compromise of 1850, and this meant a vigorous application of the Fugitive Slave Act. After the failure of the federal government to capture William and Ellen Craft, and the rescue of Shadrach, Webster sprang into action. He helped Millard Fillmore prepare a proclamation calling on all citizens to support the law, and he personally supervised the trial preparations for Shadrach’s rescuers. The indictments would come to naught—in part because Webster insisted upon prosecuting the rescuers for treason.

Not a month after Shadrach’s rescue, Thomas Sims was arrested in Boston. Sims was a fugitive from Georgia who, like Shadrach, had arrived in Boston by ship. His arrest set the Boston Vigilance Committee into motion preparing a variety of legal defenses for Sims. Petitions for habeas corpus reached the state supreme court, federal court, and the United States Supreme Court. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court afforded Sims’s lawyers the most capacious hearing, and heard the first sustained arguments on the unconstitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Lawyers for Thomas Sims understood that there was little chance of prevailing in any court. By the Supremacy Clause, Article VI Section 2, The United States Constitution and federal law was deemed to be “the supreme Law of the Land,” and the state prerogative to protect alleged fugitives in their liberty was thus trumped by the Fugitive Slave Act. To counteract explicit federal supremacy, Sims’s attorney, the celebrated Boston lawyer Robert Rantoul, Jr., argued that the Fugitive Slave Act was not a constitutional statute. He predicated this on two grounds. The first was that federal commissioners were not judges, and thus could not preside over rendition cases. The second was that the Fugitive Slave Clause conferred power on the states rather than the federal government, and thus that Congress had no power to pass any fugitive slave law.

The Massachusetts Chief Judicial Court unanimously rejected these arguments. Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw wrote an opinion declaring that the Constitution conferred authority on Congress to pass fugitive slave laws, and that rendition hearings were not formally “cases.” They were more like administrative hearings, and could be heard by commissioners. After dispensing with the constitutional objections, Shaw then made the case for the non-slaveholding states obeying the rule of law. The Supreme Court had ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, said Shaw, that Congress had the authority to pass fugitive slave laws, and it was “absolutely necessary to the peace, union and harmonious action of the state and general governments” that Massachusetts’ courts abide by this opinion.[10] Shaw refused to issue the writ of habeas corpus, Sims was returned to the custody of the marshal.

In order to avoid the embarrassment of another rescue, federal officers enlisted the help of the Boston police and called on armed volunteers. Sims was kept under heavy guard and access to him heavily restricted. In an act pregnant with unintended symbolic significance, federal officers wrapped the courthouse in chains to prevent a rush on its doors. On Friday, April 11, the federal commissioner in Boston issued a certificate of removal. The next day, over three hundred men marched Thomas Sims to a ship bound for Georgia. The federal government had succeeded in returning a fugitive slave from Boston, albeit at the cost of $20,000.[11]

Violent resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act continued. Most notoriously, slavecatchers in Christiana, Pennsylvania faced armed resistance which resulted in the death of a slaveholder and the serious wounding of three of his relatives while attempting to recapture a fugitive. The U.S. government responded forcefully, securing indictments for 41 people, although only one would ultimately be brought to trial, and he would ultimately be acquitted.

Despite the torrent of resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 and 1851, the law had its supporters. Southern support of it was robust, although many expressed skepticism that northerners would faithfully execute the law. Much of the northern support directly countered abolitionists’ appeal to the moral law by stressing its importance to uniting the United States. Daniel Webster spoke at “Union Meetings” in northern cities, urging people to respect the law and the sectional compromise measures. The law received a vigorous constitutional defense from both the bench and bar. Against claims that the Fugitive Slave Act encroached on reserved state authority, proponents argued that congressional fugitive slave legislation had been on the books since 1793, and that the U.S. Supreme Court had positively declared the power to be exclusively congressional in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842).

By 1853, tempers had cooled. Some seventy fugitives had been returned under the Fugitive Slave Act. It was a modest number, certainly when compared with estimates of the number of slaves who were annually escaping to freedom, but a success nonetheless. Public condemnation of the law had quieted, and for a time it appeared as if fugitive slave rendition would no longer be a major bone of contention for ordinary politics.

Two events helped to reopen the wounds caused by the Fugitive Slave Act in 1854. The first was the remarkable success of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published as a novel in 1852. The novel featured two parallel stories, one of which was the flight of two fugitives northward. Its immense popularity was augmented immediately by multiple stage productions and popular marketing, and it stirred popular antislavery sentiment across the free states.

The second event was Stephen Douglas’s introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska bill into the Senate in January of 1854. The bill set aside the Missouri Compromise and proposed to organize the Kansas-Nebraska territory on the principal of popular sovereignty. Slavery would no longer be prohibited north of the 36° 30’ latitude, but would now be settled by popular vote in the territories themselves. The bill provoked a furious political response in northern states. This drew new attention to fugitive slave cases and provoked a more concerted resistance to their execution.[12]

The arrest of Joshua Glover, a Missouri fugitive, outside of Racine, Wisconsin on March 10, 1854 proved the point. Federal agents took every precaution. They arrested Glover at night, sent a decoy contingent to Racine (a town with a sizable abolitionist population) and transported Glover by wagon north to Milwaukee, the seat of the U.S. Judge for the western district of Wisconsin. Yet by morning, abolitionists had been notified by wire, and a large crowd eventually gathered outside the courthouse. When the federal marshal refused even to acknowledge a writ of habeas corpus issued by a state court, the crowd broke Joshua Glover out of jail.

The rescue of Joshua Glover became national news, as did the heavily publicized prosecutions brought by the federal government in its wake. In 1855, a jury convicted Sherman Booth—Milwaukee’s most vocal abolitionist—of the crime of removing Glover from federal custody. Notably, the jury refused to convict on the one count that specified a crime under the Fugitive Slave Act. Shortly after the conviction, the Wisconsin Supreme Court released Sherman Booth on a writ of habeas corpus, under the rationale that the indictment failed to specify a statutory crime. More spectacularly, two of the three judges of the Wisconsin Supreme Court declared the Fugitive Slave Act to be unconstitutional.

The full-throated legal resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act in Wisconsin was matched by popular resistance in other states. In Boston, the arrest of the fugitive Anthony Burns brought with it a riot. Anthony Burns was a slave in Virginia, and in February 1854 he stowed away on a ship bound for Boston. For several months he lived and worked in the city, before being discovered. Burns was arrested surreptitiously on May 24, and then escorted under heavy guard on May 25 to the federal courthouse for a rendition hearing. The abolitionist lawyer Henry Dana arrived in court at the same time, having heard a rumor that a fugitive slave was in federal custody, and offered to represent Burns. Burns declined, primarily out of fear that his master would punish him for making the rendition difficult. Dana nonetheless won a continuance for Burns from the commissioner.

Word of the first fugitive slave arrest in Boston since Thomas Sims spread like wildfire in Boston. The vigilance committee met and considered action, even while Henry Dana and others prepared a legal defense for Burns. On Friday, May 26, a riot broke out in the Courthouse square and a rush was made on the jail, which was heavily fortified with marshals and their allies. The mob was repelled, but a peace officer was wounded during the melee, and eventually died.[13]

Despite the outbreak of violence, Burns hearing went forward on Saturday, May 27, 1854. After four days of testimony, evidence, and lawyers’ summations, the federal commissioner ruled in favor of the slaveholder and issued a certificate of removal for Anthony Burns. Federal marshals took no chances with another rescue attempt. Burns would be escorted by 120 special officers to the wharf to be put on a ship bound for Virginia. The slaveholders had won. The victory, however, was pyrrhic. Anthony Burns was the last slave removed from Boston, and within a year he would return after his freedom was purchased by sympathetic Bostonians.

Fugitive slave rendition after 1854 became even more difficult. The law was already heavily contested, but now it became more so. Fugitives could expect to have counsel, which raised the costs of rendition for slaveholders. Whole parts of the North were open conduits for fugitive slaves, who were treated as refugees rather than as fugitives. The threat of rescue was very real, as witnessed by the rescue of John Price in 1858. John Price was a fugitive from Kentucky and had been arrested surreptitiously by slavecatchers outside of Oberlin, Ohio. When word got out that a fugitive slave was on the road to Wellington for an extradition hearing, hundreds of Oberlin residents set out intent on a rescue. They trapped the slavecatchers at a hotel and rescued John Price.

These instances of resistance proceeded from moral grounds, holding the constitutional demand of Article IV, Section 2 as subservient to the “higher law” which made slavery illegitimate. Even moderate abolitionists who admitted that the Constitution’s commands had to be followed continued to denounce the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 as unconstitutional. The Supreme Court answered this argument in Ableman v. Booth (1859) in a unanimous opinion. Chief Justice Taney, speaking for the Court, declared that “the act of Congress commonly called the fugitive slave law is, in all of its provisions, fully authorized by the Constitution of the United States.” But this unequivocal affirmation of the Fugitive Slave Act failed to convince even the moderate abolitionists, who continued to urge that free states resist the law. [14]

For their part, southerners pointed to these same facts as proof of northern infidelity to the principles of the Compromise of 1850. When secession came, South Carolina specifically cited the failure to deliver fugitives from slavery to their masters as a deliberate refusal by northern states “to fulfill their constitutional obligations.” South Carolina called out the free states by name, accusing them each of attempting to “nullify” or “render useless any attempt to execute” the Fugitive Slave Act. South Carolina left no doubt that this was in direct violation of the constitutional compact: “in many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed, and in none of them has the State Government complied with the stipulation made in the Constitution.” This concern would be echoed by Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas in their own declarations accompanying acts of secession. [15]

Secession in 1860 and 1861 did not serve to quell the fugitive slave issue. The border states of Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri still held slaves, and Abraham Lincoln entered office committed to the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. While Lincoln expressed the moderate abolitionist preference for a new law which would better safeguard the liberties of free blacks, he did not insist upon it. In any case, enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act in Union states took a back seat to other administrative priorities. Republicans, despite being firmly in control of Congress, failed on several occasions to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act. Finally, in 1864, Congress repealed both the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, and Lincoln signed the repealing legislation. A year later, the Thirteenth Amendment ended forever the problem of fugitive slaves in America.

- [1] The first “personal liberty laws” were anti-kidnapping statutes, and they predate the Constitution. In the 1820s, states began passing more muscular anti-kidnapping laws that also regulated rendition under the Fugitive Slave Act. Pennsylvania and New Jersey passed laws in 1826, New York in 1828, and a host of other states in the 1830s.

- [2] Stanley Harrold, Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

- [3] H. Robert Baker, “The Fugitive Slave Clause and Antebellum Constitutionalism,” Law & History Review 30, no. 4 (November 2012): 1133–74.

- [4] Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539 (1842).

- [5] H. Robert Baker, Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012).

- [6] Cong. Globe, 31st Cong., 1st Sess., 233 (1850).

- [7] Gautham Rao, “The Federal Posse Comitatus Doctrine: Slavery, Compulsion, and Statecraft in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America,” Law and History Review 26, no. 1 (Spring 2008), http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=7789394&fulltextType=RA&fileId=S0738248000003552 , accessed June 29, 2015.

- [8] “Faneuil Hall Mass Meeting,” Emancipator & Republican (Boston), October 17, 1850; “The Fugitive Slave Law,” North Star (Rochester, NY), October 24, 1850.

- [9] Steven Lubet, Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), 134-5.

- [10] Thomas Sims’s Case, 61 Mass. 285, 310 (1851).

- [11] Don Edward Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 233-4.

- [12] Stanley W. Campbell, The Slave Catchers; Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 79.

- [13] Earl M. Maltz, Fugitive Slave on Trial: The Anthony Burns Case and Abolitionist Outrage (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010).

- [14] Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 506, 526 (1859).

- [15] “Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” adopted December 24, 1860 from The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp, accessed June 29, 2015.

If you can read only one book:

Lubet, Steven. Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.

Books:

Baker, H. Robert. The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006, 26-57.

———. Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

Brandt, Nat. The Town That Started the Civil War. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990.

Campbell, Stanley. The Slave-Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

Finkelman, Paul. An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980, 236-84.

Fehrenbacher, Don. The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, 205-52.

Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W. W. Norton, 2015.

Harrold, Stanley. Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Maltz, Earl. Slavery and the Supreme Court, 1825-1861. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

———. Fugitive Slave on Trial: The Anthony Burns Case and Abolitionist Outrage. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010.

Slaughter, Thomas P. Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

von Frank, Albert J. The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson’s Boston. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The Library of Congress’ American Memory Exhibit: Abolition, Anti-Slavery movements, and the Rise of the Sectional Controversy: Part I, the Fugitive Slave Law provides a brief summary of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The full text of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 is provided on the Avalon Project website.

The Library of Congress’ American Memory Exhibit: A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation includes U.S. Congressional Documents and debates from 1774-1775, available on line.

Freedom on the Move is a database of Runaway Ads used to try to locate fugitive slaves at Cornell University. The ads provide information about the economic, demographic, social, and cultural history of slavery.

The Texas Runaway Slave Project is a database of runaway slave advertisements, articles and notices from Texas newspapers at the east Texas Research Center.

The Geography of Slavery in Virginia is a digital collection of advertisements for runaway and captured slaves and servants in 18th and 19th century Virginia newspapers at the University of Virginia.

The Library of Congress’ American Memory Exhibit: Slaves and the Courts, 1740-1860 is a collection of pamphlets and books concerning the difficult and troubling experiences of African and African-American slaves in the American colonies and the United States.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.