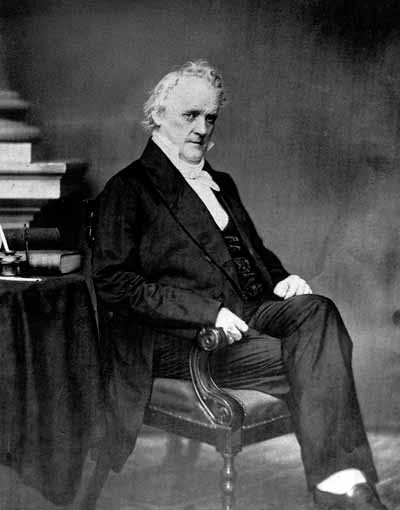

James Buchanan

by Jean H. Baker

James Buchanan, 15th President 1857-1861, was unable to provide the leadership to resolve the crisis over the union leading up to to start of the Civil War.

In the summer of 1856 delegates to the Democratic convention meeting in Cincinnati nominated James Buchanan as their candidate for president. It was a popular choice, and in Buchanan’s mind, an overdue honor from the party that the Pennsylvanian had long served in a number of capacities. In the customary manner of 19th century elections Buchanan did not campaign; in this period of American history any entreaties to the electorate, besides a few letters, local remarks or speeches by surrogates, were viewed as violations of the national understanding that public office was a gift conferred by the people through the exercise of their free will. Earlier Buchanan had pledged to support the party platform, though on the perplexing issue of slavery in the territories, he had never accepted the party’s commitment to popular sovereignty—that is, the policy of the Illinois Senator Stephen Arnold Douglas that the people of a territory could decide for themselves whether to accept or prohibit slavery. Instead he embraced the pro-southern position that slaves were property and as such could be taken into the territories.

In this presidential year of sectional division when the dramatic caning of Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate by a southern member of Congress ,Buchanan made known his view that the Union was in danger and that only by adhering to the United States Constitution could it be saved. He had already located the culprit responsible for the nation’s political disharmony in the new Republican Party. As he wrote a Pennsylvania Democrat during the summer, “the Union is in danger and the people everywhere begin to know it. Black Republicans must be boldly assailed as disunionists and the charge must be reiterated again and again.”[1]

Months later, in the three-way presidential election that featured John Charles Frémont, the first Republican presidential candidate along with Millard Fillmore, the nominee of the Know Nothing or American Party, Buchanan was elected the fifteenth president of the United States. He won with an impressive forty-five percent of the popular vote and 174 Electoral College votes out of 296. By selecting James Buchanan Americans had chosen an experienced diplomat and popular Democrat. Indeed few politicians could match Buchanan’s record of public service.

Born in Cove Gap, Franklin County, in southern Pennsylvania in 1791, Buchanan graduated from Dickinson College. He then moved to Lancaster where he studied law. After a brief period in a successful law practice, he ascended nearly seamlessly through a sequence of political victories in his home state. In the 1820s he served in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the 1830s and 1840s he was elected to five terms in the United States House of Representatives and two in the Senate. In fact in his long public career he was defeated only once in eleven attempts for legislative office, though his presidential ambitions took longer to achieve. Amid talk of an appointment to the Supreme Court, instead in 1845 President James Polk appointed Buchanan secretary of state. With Polk he oversaw the spectacular expansion of the nation after the Mexican-American War and the ratification of the Oregon Treaty. In 1852 he anticipated receiving his party’s presidential nomination, only to be disappointed when the party chose Franklin Pierce.

When Pierce was elected, Buchanan accepted the position of minister to Great Britain, a position that removed him from any direct association with the controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and enshrined the principle of popular sovereignty in those two territories. It was also the catalyst for the formation of the Republican Party, whose supporters refused to accept the extension of slavery into the territories. From London Buchanan watched the increasing animosity between northerners and southerners over the role of slavery in the territories and the issue of fugitive slaves in the Border States. By this time many Americans knew Buchanan by his nickname “Old Public Functionary,” a man depicted as an old man (he was 65 when he was elected president) who had lived nearly his entire professional life in both elected and appointed public office. His friends preferred to call him “Old Buck.”

is friends preferred the

As he reached the pinnacle of his ambitions, Buchanan intended to solve the growing friction between North and South. A loyal member of the Democratic Party, he represented one of the few remaining national institutions in the United States in the 1850s. Churches had already split into northern and southern factions; angry rhetoric inflamed the halls of Congress. Buchanan endlessly repeated his support for the Union and the Constitution, believing his Republican opponents to be a sectional faction of zealots. Yet when Buchanan turned the nation over to his Republican successor, Abraham Lincoln, he left in disgrace, condemned by Republicans, vilified by northern Democrats and even dismissed by the southerners whom he had tried to placate and whose personal affection as a lonely bachelor he had sought. Like his contemporaries, modern historians consistently place James Buchanan among the least successful presidents. Thus the central question of Buchanan’s administration is why did such a well-meaning and experienced public figure fail so miserably? Were the problems over slavery insurmountable? And more appropriately to an evaluation of his administration, did he contribute to the disruption of the Union and to the creation of the Confederacy?

In his long inaugural address delivered in March 1857, Buchanan offered solutions to the growing divisions in the nation. First, Congress had no legitimate role in the decisions that territories made about slavery; only the will of the people at the moment of achieving statehood could prohibit the right of individuals to settle in any territory with their private property in slaves. Some southerners, such as Jefferson Davis, were extending this position to argue that slavery followed the flag and must be safeguarded by the federal government. Personally Buchanan deplored slavery but given his conservatism and pronounced sympathy for the South, he argued that the “sacred right of each individual (by which he meant white males) must be preserved.” The agitation of the issue by northern abolitionists and their surrogates the Republican Party produced “great evils to the master, the slave and to the whole country.” [2]

Buchanan’s solution rested with his expectation that the courts would solve this mid-19th century dilemma dividing Americans. Like most politicians he was well aware of the judicial case involving the status of Dred Scott, a Missouri slave who had lived in free territory and now sought his liberty on that basis. For the new president the case seemed an opportunity to end forever the controversial slave issue and to achieve what he so sincerely sought: national harmony. That achieved, he could turn his attention to the incorporation of new territory in Mexico and Cuba, which as a fervent supporter and architect of Manifest Destiny, would be his presidential legacy. In fact even as president –elect, he had inquired among the judiciary about the status of the case and, in an inappropriate intrusion that might lead to impeachment today, he had prodded his friend Robert Grier, a Supreme Court justice from Pennsylvania, to render a comprehensive decision that went beyond the particulars of Dred Scott’s circumstances.

Indeed the president already knew the intricacies of the Dred Scott decision that was handed down two days after his inauguration; no black in the United States had any rights that the white man was bound to protect. Hence Dred Scott could not sue for his freedom. Beyond the specifics of Scott’s case, as human property protected by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, slavery now could not be prohibited before statehood. Thereby slavery was nationalized. Even northern Democrats were troubled by the future of a republic founded on freedom and liberty that, by virtue of its highest court and encouraged by its new president, so blatantly promoted the enslavement of human beings.

Although Buchanan expected otherwise, in fact the Dred Scott decision only heightened the tension between the North and South. But in Washington Buchanan found support for his views from his cabinet that met every afternoon for several hours, save for Sunday. In the early months of his administration these men served as a sounding board for his positions, offering their own pro-southern views to the man they dubbed “the Squire.” Later with some new additions in the crisis-filled last days of his administration, the president sought emotional support from a group that served as family to a beleaguered bachelor.

Before his inauguration, of seven members he chose four officers from the South and three northerners who supported southern interests, the latter despised as “doughfaces” for their malleable, sectional prejudices. All four of the southerners had been at one time or another, large slave-owners, and Buchanan’s favorite, Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb of Georgia, had once owned over one thousand slaves. Only one of the cabinet’s officers came from the growing population west of the Appalachians, and there were no northern Democrats who followed the principles of popular sovereignty popularized by Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas. This president wanted no team of rivals, no alternative voices.

Indeed his lax oversight of the cabinet led to a culture of corruption that ended in an embarrassing congressional investigation and Buchanan’s near impeachment. Army forts were sold to private interests and Interior Department funds embezzled. But even more destructively, in the case of Secretary of War John Buchanan Floyd, significant shipments of arms were sent south in anticipation of civil war. So much was diverted to the South that Confederate military commanders later acknowledged Floyd’s contributions to their effectiveness.

Almost immediately Buchanan confronted the first great crisis of his administration: what to do about Kansas. By the time he assumed the presidency there were already two competing territorial governments in an area to be organized under the Kansas-Nebraska Act which mandated that the people of the territory determine the fate of slavery. One territorial government with a proslavery legislature and judiciary was now located in a small town along the Kaw River called Lecompton. The other was the free-state government located in Topeka, three miles to the west. Both groups had moved aggressively to create governments, adopting constitutions and electing a legislature. Yet many settlers, indifferent to slavery, cared more about their prospects of settling on fertile land, while others wanted to ensure that they did not compete with slave labor.

By law the president chose the territory’s governor, but when his choice Governor Robert John Walker threw out the obviously inflated returns from several counties and resisted the claims of the Lecompton government, Buchanan removed him. Nor did the president listen to the entreaties of Kansans who supported by clear majorities the free- state government. He refused to listen to the three former territorial governors, or to most of the northern wing of the Democratic Party, especially Stephen Douglas, who encouraged him to reject the Lecompton constitution. And he never listened to the Republicans whom he despised. Instead he made the vote on the proslavery Lecompton constitution a party vote, thereby increasing the prospects of a divided Democratic party.

By 1860, the last full year of his presidency, Buchanan faced an increasingly aggressive South that had been emboldened by his clear partiality toward its interests. And as southerners began the process of taking over coastal forts Buchanan did nothing. He was further undermined when at his party’s presidential nominating convention in Charleston, South Carolina; Democrats divided over their policies toward slavery in the territories and eventually nominated two candidates. Of course Buchanan supported the southern wing of the party led by John Cabell Breckinridge of Kentucky, which now demanded that the federal government protect slavery in the territories and enact a federal slave code. And when Lincoln won both the popular vote and the Electoral College vote in this four-candidate election, Buchanan continued to espouse his policy of the equality of states, code-words for the property rights of southern slave-owners.

Immediately after Lincoln’s election Buchanan faced the most personally wrenching crisis of his public life when southerners who had threatened secession for years actually began the process of destroying the Union. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott promptly urged the immediate garrisoning of federal forts with sufficient troops to prevent a surprise attack. But Buchanan did nothing as, like dominoes, seven southern states seceded in the winter of 1860-1861. Buchanan believed that while secession was illegal, any coercion by the federal government was also illegal—a view that led Senator William Henry Seward to observe that what Buchanan espoused was that no state had a right to secede unless it wanted to and the government must save the Union unless somebody opposed it. Meanwhile southern members of his cabinet abandoned the president and went home to what became in February 1861 a new government, the Confederate States of America.

Soon the controversy over federal authority focused on the forts in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor. The Union commander there, Major Robert Anderson, had moved his forces from the indefensible Fort Moultrie located on a peninsula protected only by high sand dunes from an increasingly threatening South Carolina militia. On Christmas night 1860 Anderson took his sixty soldiers to Fort Sumter, a far more defensible location in Charleston Harbor. But the president, in the midst of negotiations with commissioners from the south, initially intended to send Anderson back to Fort Moultrie, an effective surrender given the ease with which South Carolinian forces could overrun that installation. Such a policy was as well an implicit recognition that the Union would not contest the southern takeover of national property. Buchanan insisted that Anderson had exceeded his orders, but when Anderson’s orders were later produced by the War Department, the commander had indeed been authorized to locate his force in the most defensible of the Charleston forts, if he had “tangible evidence” of impending hostilities. That more defensible choice clearly was Fort Sumter. Meanwhile the president offered a truce based on the passage by Congress of a constitutional amendment guaranteeing slavery in the states and territories and the enforcement of the rights of southerners to reclaim their escaped slaves in the North. In all Buchanan’s plans the rest of the United States and especially the Republicans (though they had won the recent election) must make adjustments to southern demands.

By this time Buchanan’s cabinet, without the southerners who had left for the Confederacy, included three northern Unionists. These men—Jeremiah Sullivan Black, Edwin McMasters Stanton, and Joseph Holt informed the president that to order Anderson back to Moultrie was treason. They would resign if Buchanan did not change his plans. The president, in an unusual gesture, asked his Secretary of State Black--who believed that no American would support Buchanan’s surrender of federal property and forces--to write a more forceful statement of federal authority over its installations. Yet keeping the fort was a minimal gesture from the point of view of asserting the power of the federal government. What Buchanan did not do in the perilous days of the secession winter of 1860-1861 is worth noting: he did not order 16,000 US Army troops back from their western posts. He did not reinforce any of the offshore forts.

He did not challenge South Carolinians as President Andrew Jackson had done in his confrontation with that state in the 1830s. Consequently, empowered by the abandonment of any authority over them, the future Confederacy gained in confidence, organization and supplies. And while in January the president did agree to an abortive effort to send men and supplies to Anderson, he never authorized Anderson to respond with covering fire when that expedition reached Charleston Harbor and was fired upon. Hence when the batteries in Charleston opened fire—a clear act of war—the expedition simply turned around and moved out to sea without delivering its troops or supplies. And so the surrender of Fort Sumter awaited Lincoln’s administration when an attack on the flag brought a different response.

Finally in March the 120 days of Buchanan’s lame duck presidency ended, and the new Republican President Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated. Anticipating a possible Confederate coup d’état General Winfield Scott asked Buchanan to order extra troops into Washington to preserve the peace during Lincoln’s inauguration. This the outgoing president refused. On the ride back from the inauguration Buchanan famously turned to his successor and indicated that if Lincoln was as happy entering the White House (as indeed Buchanan had been four years earlier) as Buchanan was leaving for his beloved home Wheatland in Lancaster, then Lincoln was a happy man. Once in retirement Buchanan supported the Union, opposed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and devoted himself to writing a long exculpatory version of his administration entitled Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion.[3]

Some historians have classified Buchanan as indecisive; others have argued that he was controlled by his pro-southern cabinet, and still others that he was too old to take command of the government during the secession winter.

In fact Buchanan’s failing during the crisis over the Union was not inactivity but rather his partiality for the South, a favoritism that bordered on disloyalty in an executive officer who had sworn an oath to protect and defend the flag of all the United States. By any measure Buchanan appeased the South; he allowed his cabinet officers to send weapons to the South; he did everything possible to try to assure that Kansas became a slave state; he allowed southerners to gain time and confidence so that when the war started the North faced a powerful enemy.

Overall Buchanan was a stubborn ideologue whose principles held no room for compromise. He went beyond normal partisan antagonism to castigate the Republicans, a legitimate political party, as disloyal; and he persistently underestimated the popularity of their views. His intransigence split his own Democratic Party as he continued to hold the North responsible for the sectional disruption. When South Carolina seceded in December, he did nothing and such appeasement only encouraged the Confederacy, even though American history displayed precedents of executives calling out the militia to confront an insurrection in Washington’s, Jackson’s, Taylor’s and Fillmore’s administrations.

Clearly as a leader Buchanan failed to understand the changing attitudes of most Americans. He failed to understand the nation, the result of a stubborn overconfidence that emanated from a combination of his character, pro-southern sympathies and a lifetime spent in partisan political roles.

James Buchanan

- [1] James Buchanan to J. Glancy Jones, June 27, 1856, John Cadwalder Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania..

- [2] James Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908), 5:454; Ibid, 627..

- [3][3] James Buchanan, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion (New York: D. Appleton, 1866).

If you can read only one book:

Baker, Jean H. James Buchanan. New York: Times Books, 2004).

Books:

Auchampaugh, Philip Gerald. James Buchanan and His Cabinet on the Eve of Secession. Lancaster, PA: privately printed, 1926).

Binder, Frederick. James Buchanan and the American Empire. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 1994).

Birkner, Michael, ed. James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 1996).

Buchanan, James. Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. New York: D. Appleton, 1866.

Curtis, George. The Life of James Buchanan, Fifteenth President of the United States. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1883.

Quist, John and Michael Birkner, eds. James Buchanan and The Coming of the Civil War. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, forthcoming.

Smith, Elbert. The Presidency of James Buchanan. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1975.

Organizations:

Lancaster County’s History Society

The Society mission is to educate the public on the history of Lancaster County and to promote the acquisition, preservation, and interpretation of resources representing the history of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania including the life and legacy of America's fifteenth president, James Buchanan, and to preserve and maintain Wheatland, his home. 230 N. President Ave. Lancaster, PA 17603-3125 (717) 392-4633, (717) 392-8721

Web Resources:

The National Parks Service American Presidents website provides information on 75 historic places associated with American Presidents. Wheatland, James Buchanan’s home is featured on this URL.

Other Sources:

Buchanan Papers at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

James Moore, ed., The Works of James Buchanan comprising his speeches, private papers and state correspondence. 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 732-6200