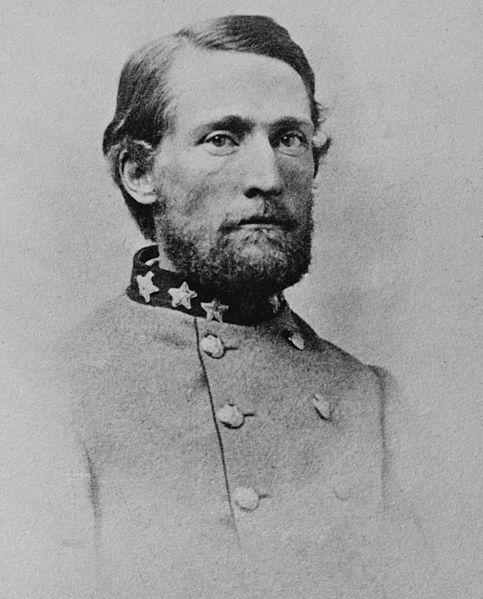

John Singleton Mosby

by Eric W. Buckland

"My purpose was to weaken the armies invading Virginia, by harassing their rear... to destroy supply trains, to break up the means of conveying intelligence, and thus isolating an army from its base, as well as its different corps from each other, to confuse their plans by capturing their dispatches, are the objects of partisan war. It is just as legitimate to fight an enemy in the rear as in the front. The only difference is in the danger ..."[1]

— Col. John S. Mosby, CSA

Perhaps no other individual’s name from the War Between the States is more inextricably intertwined with the unit he commanded than John Singleton Mosby. That unit, the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, was commonly known as Mosby’s Rangers. It was, unquestionably, his command. Certainly, it bore his name, but more importantly, the unit’s inception, expansion, successes and viability up to the final days of the war were a direct result of his operational vision, audacity, self-confidence and stoic endurance. Mosby commenced irregular operations with just nine men loaned to him by Major General James Ewell Brown “JEB” Stuart in early 1863. At that time, Mosby had no rank and was a scout for Stuart. On April 21, 1865, having achieved the rank of Colonel, Mosby would disband rather than surrender his command which contained over 800 men.

In 1992, Colonel John Singleton Mosby was a member of the first group of men honored with induction into the United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame. Mosby’s investiture into the United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame paid specific tribute to his “discipline within his command, knowledge of Ranger tactics, and high dedication to the mission, even when wounded” and recognized, in general, his superior attributes as a leader and warrior. It was a singularly outstanding honor made extraordinary because he was honored by the same organization which provided the targets by which he achieved his success and fame, the United States Army.[2]

John Singleton Mosby was born in Powhatan County, Virginia on December 6, 1833. Although “Jack”, as he was known at home, was a very bright boy, he was small and frail. He was not expected to live a long or robust life.

Unlike most boys of his era, Mosby often shied from the excitement of outdoor forays and physical exertion. Rather, he sought his adventures through reading. He developed a keen passion for the Greek Classics, and would reference them throughout his life. He also favored biographies such as The Life of General Francis Marion by M. L. “Parson” Weems. As an adult, Mosby would recall his youthful delight at the way Marion, the Swamp Fox, outwitted his British enemies during the Revolutionary War.

Mosby’s parents made his education a priority. He began his schooling in Powhatan County when he was just six or seven years old. When his family moved to a new home near Charlottesville, Virginia in about 1840, he was enrolled in classes in Fry’s Woods. At age ten, he transferred to a school in Charlottesville.

Given his small size and general physical weakness, it is not surprising that Mosby had a difficult time fitting in at school. He became a target for frequent, sometimes brutal, bullying. In what may have been a portent of his behavior as a partisan leader, Jack Mosby did not back down, no matter how badly the odds were stacked against him. He repeatedly chose confrontational valor rather than discretionary surrender or retreat.

Mosby lost nearly all of these boyhood fights. But they may have been the source of a tactic—launching unexpected, vigorous strikes rather than standing passively while awaiting an enemy’s attack —that he applied to great effect in later years.

The image of a frail boy stubbornly standing his ground in the schoolyard and getting the stuffing knocked out of him time and time again dominates the first chapter of the traditional Mosby saga. To some, the notion that such a stripling would grow up to become a fierce leader of men, repeatedly defying death and overcoming incredible military odds, may smack of fiction. But in many ways, the truth of Mosby’s life is more compelling than any storyteller’s invention.

Two months short of his seventeenth birthday, Mosby entered the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was during his third year at UVA that the next significant “chapter” of his story would be written with the help of a pepper-box pistol.

It started with a social conflict. Mosby had been planning a party and had extended invitations to a pair of young men of his acquaintance. While the two were well known as accomplished musicians and undoubtedly would have added a level of gaiety to the festivities, it is unclear whether Mosby solicited their attendance as entertainers or as friends.

As it happened, another young man, George Turpin, was organizing a similar fete for the same day. He also wanted the two musicians at his party.

When Turpin discovered that Mosby had already laid claim to the musicians’ attendance, he made very public insinuations that his rival party host had issued his invitation to the pair under false pretenses. According to him, Mosby might claim he’d asked the two men to come to his event as guests, but his true intention was to have them provide the entertainment.

Mosby, quite naturally, considered Turpin’s comments an insult. But Turpin was a far more dangerous adversary than the schoolyard bullies of his pre-teen years. A large, heavily muscled young man with violent tendencies, Turpin had already crushed the head of one UVA student with a brick and stabbed another multiple times.

Forced to choose between risking serious injury by standing up for himself or appearing to be a coward by letting the slur against him go unanswered, Mosby once again opted to face his enemy. He sent Turpin a message demanding an explanation of his accusations. Turpin responded with a threat. .

Mosby prepared himself for what he knew would be a perilous – possibly even deadly – confrontation with Turpin by acquiring a small handgun called a pepper-box pistol. A few days later, Turpin appeared at the boarding house where Mosby lived. Words, decidedly unfriendly, were exchanged.

While it remains unclear how the violence actually erupted, there is no confusion about how it ended. Turpin was sprawled on the floor, blood flowing from a wound in his neck. Mosby stood over him, a smoking pistol in his hand.

As it turned out, Turpin’s injury looked far more serious than it actually was and he enjoyed a full recovery. But while Mosby escaped the episode physically unscathed, it cost him dearly.

Within days of the incident, 19-year-old John Singleton Mosby was arrested on two charges: the first was unlawful shooting, a misdemeanor with a maximum sentence of one year in jail and a $500 fine and the second, malicious shooting, a felony with a maximum sentence of 10 years in the penitentiary. He was promptly tried and convicted of unlawful shooting. The maximum sentence and fine were imposed.

Ironically, Mosby’s career aspirations were furthered by his conviction and incarceration. He befriended the man who had prosecuted him, William Robertson, and informed him of his interest in studying the law. Robertson, who felt empathy for the young Mosby, agreed to make his law books available to the prisoner.

After a series of appeals by his family and friends, Mosby was pardoned for his crime on December 23, 1853 and released from jail. He continued his law studies under the tutelage of Mr. Robertson and was admitted to the bar.

On December 30, 1857, Mosby married Pauline Clarke. Pauline, a strong and courageous woman, would prove to be an equal partner in the marriage. By 1859, the couple had settled in Bristol, Virginia with Mosby practicing law and Pauline keeping house. They eventually had eight children together, six of whom survived childhood. Pauline died on May 10, 1876 as a result of difficulties precipitated by the birth of the eighth child and leaving John Mosby a heart-broken widower.

As John and Pauline built their happy family life, the division between North and South deepened. The threat of war became increasingly serious.

Mosby, a Unionist, did not think highly of the vitriol-laced diatribes against the federal government. While he joined a local militia unit in the summer of 1860, he was responding more to a sense of social obligation than the prodding of political conviction or Southern loyalty. He also proved to be an indifferent soldier and even failed to attend the first meeting of the unit.

Things changed radically in April of 1861 when Virginia voted to secede. As Mosby succinctly recorded in his memoirs, “Virginia went out of the Union by force of arms, and I went with her.”[3]

Mosby had joined the Washington Mounted Rifles, a cavalry company formed by men from the area surrounding Bristol, Virginia. The company was commanded by Captain William Edmondson “Grumble” Jones, an eccentric, prickly and tough 1848 graduate of the United States Military Academy. Despite his difficult personality, Jones knew cavalry drill and tactics and pushed his recruits hard. John Mosby, then about 27 years old, came to see Jones as a capable commander and teacher. The two men spent many evenings talking about military operations and the use of cavalry. The future Ranger recognized in the rough-edged Jones a leader who cared about the welfare of his men.

Although Mosby’s health was relatively poor when he entered the cavalry as a private, it soon began to improve. While he wasn’t transformed into a physically imposing figure—most historians agree that Mosby was no more than 5’ 7” tall and never weighed more than 130 pounds—he gained strength, stamina and toughness. Mosby discovered that he reveled in the hardships of a soldier’s life. He also quickly developed an intense dislike for the routine drudgery of daily camp activities and eagerly volunteered for scouting or picket and vidette duty. He was most alive when in the saddle, away from camp, and as close as possible to the enemy.

The Washington Mounted Rifles became a part of the newly organized 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment commanded by JEB Stuart. Given the wide separation of rank and position between Private Mosby and Colonel Stuart at the time, neither foresaw the close relationship that would develop between them.

While the 1st Virginia was engaged in the First Battle of Manassas, Mosby’s personal involvement in the fight was limited to being the target of some long-range enemy artillery fire and briefly chasing Union forces as they retreated from the field in defeat. A few weeks after the battle, Stuart was promoted to Brigadier General and Jones assumed command of the 1st Virginia. Mosby became Jones’ Adjutant and received a commission as a First Lieutenant.

Seeking to avoid the humdrum routine of camp life and the distasteful administrative tasks of an adjutant, Mosby participated in patrols as often as possible. It was during one of those patrols that Mosby’s skills as a scout and his unflappable demeanor under stress came to Stuart’s attention. Further encounters between the two increased Stuart’s respect for Mosby’s talents in the field.

In the fall of 1861, when even the most optimistic Southerner had been forced to accept that the war was not going to end quickly, the Confederate States’ Army began a comprehensive reorganization. Included in the many changes was a privilege given to soldiers that allowed them to elect the officers who would lead them. The hope was that providing the volunteer soldiers a “democratic” say in choosing their leaders would entice men into enlisting or, in the case of those already in the Army, signing up for another hitch.

As might be expected, more than a few officers were elected to command based on popularity rather than military prowess. When votes from the election conducted in the 1st Virginia Cavalry were tallied, Grumble Jones had been voted out and the more personable Fitzhugh Lee voted in.

There was an antipathy between Lee and Mosby. Even if Mosby had thought that Lee would want to retain him as the Regimental Adjutant, he had no desire to work under him. Seeing no other option, Mosby resigned his position as Adjutant, gave up his commission as first lieutenant, and returned to the ranks as a Private. The situation was deeply humiliating.

Luckily, Stuart heard of Mosby’s loss of position and rank and invited him to join his own staff as a courier. This was a ruse: Stuart actually wanted Mosby to act as a scout. The General further demonstrated his respect for the newly demoted private by regularly referring to him as “Lieutenant” or even “Captain” Mosby.

John Mosby might have drifted off into historical obscurity had Stuart not reached out to him. Mosby never forgot this kindness. He began to “repay” Stuart by immediately proving his value as a scout. But he never forgot the circumstances that had led to his needing Stuart’s help. When he rose to command his own unit—the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry—there was nothing “democratic” about the way his subordinate officers were selected.

By the spring of 1862, Mosby was well known to Stuart’s staff and the men who accompanied him on various scouting patrols. Outside that small, specific operational sphere, there was little if any recognition of his aptitude as a small unit leader. This would change in June of 1862 when Stuart dispatched Mosby to scout for a way to move around the flank of George McClellan’s army, which was threatening the Confederate capitol city, Richmond.

Mosby discovered a route and hastened back to Stuart to make his report. Stuart, audacious and daring, and not one to pass up an opportunity to gain fame and praise in Southern newspapers, seized on Mosby’s information and developed a plan to exploit the intelligence. The result was the famous “Ride Around McClellan” and earned Stuart a hero’s acclaim from the Southern people. At the conclusion of the spectacularly successful operation, Stuart singled Mosby out for high praise in his after-action report to General Robert E. Lee.

Two months prior to Stuart’s Ride, the Confederate States’ Government had approved the Partisan Ranger Act. Written with an understanding that many Southern men were willing to fight for their new nation as long as they weren’t required to travel far from their homes and families to do so, the Partisan Ranger Act was designed to capitalize on the desire of Southern men to conduct war on their own terms

The Partisan Ranger Act stated:

Section 1. The congress of the Confederate States of America do enact, That the president be, and he is hereby authorized to commission such officers as he may deem proper with authority to form bands of partisan rangers, in companies, battalions, or regiments, to be composed of such members as the President may approve.

Section 2. Be it further enacted, that such partisan rangers, after being regularly received in the service, shall be entitled to the same pay, rations, and quarters during the term of service, and be subject to the same regulations as other soldiers.

Section 3. Be its further enacted, That for any arms and munitions of war captured from the enemy by any body of partisan rangers and delivered to any quartermaster at such place or places may be designated by a commanding general, the rangers shall be paid their full value in such manner as the Secretary of War may prescribe.[4]

Shortly after Stuart’s ride, Union General John Pope was brought east, ostensibly to take command of the Army of Virginia and defeat Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. . He was very clear about his military strategy, publicly stating: “Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.”[5]

Pope’s blustering proclamation intrigued Mosby who later wrote, “At this time I was at cavalry headquarters, in Hanover County, about ten miles from Richmond. When I read what Pope said about looking only to his front and letting his rear take care of itself, I saw that the opportunity for which I had longed had come. He had opened a promising field for partisan warfare and had invited, or rather dared, anybody to take advantage of it.”[6]

Mosby, who reveled in operating in small groups away from the interference of staff officers and who chafed under the restrictions of daily military camp life, began to formulate a plan of action. Knowing that the promise of plunder would draw men to an irregular unit, his vision involved leveraging the tenets of the Partisan Ranger Act for his very specific recruitment and command purposes. He saw Pope’s open contempt for the rear as a prime opportunity for military attack and exploitation.

Once McClellan’s threat to Richmond had been halted and Stuart’s Confederate Cavalry were no longer engaged on a large scale, Mosby presented his concept of conducting operations behind Union lines to Stuart. Although the dashing cavalryman was intrigued by Mosby’s idea, he knew that more mounted operations were in the offing. He informed Mosby that he could not spare any men.

And yet, Stuart seemed to take pains not to completely extinguish his scout’s enthusiasm. After refusing his request for men, Stuart told Mosby that he would send him to work with Major General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson.

Unfortunately for Mosby, he had only just begun his trip to join Jackson when he was captured by a detachment of the 2nd New York Cavalry at Beaver Dam Station (about 35 miles Northwest of Richmond) on July 20, 1862. He was held as a prisoner of war for less than three weeks before being exchanged. But rather than commencing a career as an irregular warrior under Jackson, he spent another four months scouting for Stuart. During those four months, Mosby did exemplary work in connection with Lee’s Second Manassas and Maryland Campaigns and solidified Stuart’s trust in him.

It was not until late December 1862, after Stuart’s “Christmas Raid” had concluded and his command was resting for a few days in Northern Virginia’s Loudoun County that Mosby was given a full-fledged opportunity to test his vision of operating with a group of men behind Union lines. Just before returning with his command to winter quarters in the area around Fredericksburg, Virginia, Stuart informed Mosby that he would be left behind with nine men. Their mission would be to operate behind the Union lines and disrupt their lines of communication and wreak as much havoc as possible. In plain language, Mosby’s mission was to cause Union forces to worry about what was behind them and to make them bleed off resources that had been destined to engage Lee’s main army. Mosby understood his mission, “In general my purpose was to threaten and harass the enemy on the border and in this way compel him to withdraw troops from his front to guard the line of the Potomac and Washington. This would greatly diminish his offensive power.”[7]

As 1863 began, Mosby and his small band of intrepid raiders commenced operations. Two weeks later in mid-January, Mosby and his men rode to Fredericksburg, Virginia to report to Stuart. They brought with them almost thirty Union cavalry prisoners plus the captured men’s horses, equipment and weapons. Stuart, pleased by the results of Mosby’s efforts, increased to fifteen the total number of men he loaned to Mosby and instructed him to return to Northern Virginia to continue his operations.

Returning to Loudoun County with his small detachment of experienced cavalry soldiers—all were members of the 1st Virginia Cavalry—Mosby instituted two standard operating procedures. First, he had the men seek housing in local private homes; there would be no camps or camp life drudgery in his command. Mosby, and his men, would live by the old military adage “if you have nothing to do, don’t do it here.” Second, he gave the men a time and a location for their next rendezvous and sent them on their way. Mosby, and later his subordinate leaders, operated under the expectation that the men would follow orders and report at the requisite time and place. A rule was soon in place that expelled from the unit any man who missed two rendezvous in a row.

Before leading this new group of men on their first raid, Mosby spent several days scouting and learning as much as possible about the surrounding countryside and enemy activities. His unwavering thirst for current intelligence concerning possible targets or threats to his command was a key ingredient in the immediate and continued success of his operations. In addition to his personal reconnaissance missions, Mosby always sought to recruit men with exceptional knowledge of his area of operations as scouts. The skills of these men enabled the Rangers to move stealthily along trails and country roads of which the enemy was unaware. The first scout recruited by Mosby was John Underwood who had an intimate knowledge of Fairfax County. Later, Bushrod and Samuel Underwood, John’s brothers, would join the command and carry on John’s scouting duties when he was killed in late 1863. John Russell, a native of the Shenandoah Valley, and Walter “Wat” Bowie, from Maryland, both brought to Mosby’s command scouting skills similar to those of the Underwood brothers. They would prove to be of great benefit to the unit when it operated in their respective backyards. It must be remembered, too, that many of Mosby’s men had grown up hunting and playing along the country roads and in the woods where they were now operating and that gave Mosby a very real and distinct advantage almost as soon as he began his operations.

It was Union Colonel Sir Percy Wyndham, a British mercenary who had been knighted by Victor Emmanuel in 1860 for his service under Garibaldi in Italy, who suffered first from Mosby’s initial raids. In command of the Union cavalry brigade responsible for protecting the outer ring of Washington City’s defenses with a line of cavalry outposts strung through western Fairfax County, Wyndham began to frequently lose men to Mosby’s forays. Incensed at the Rangers’ manner of operating primarily at night and in small groups, Wyndham sent a message to Mosby calling him nothing more than a common horse thief. Mosby “did not deny it, but retorted that all the horses I had stolen had riders, and that the riders had sabres, carbines, and pistols.” Eventually, the exchange of taunts between the two brought Mosby to the state of wanting to teach Wyndham a lesson and resulted in, arguably, Mosby’s most famous undertaking The Fairfax Court House Raid.[8]

Mosby had already been considering a raid deep behind Union lines when, in early February, a Union deserter from the 5th New York Cavalry rode up to where Mosby and his men were meeting and expressed his desire to join them. The Union man was named James F. Ames and as a Sergeant in the 5th New York, he was familiar with the location of Union picket posts and cavalry outposts in Fairfax County. Armed with Ames’ knowledge and his own personal scouting experiences in and around Fairfax County, Mosby believed he had all of the information he needed to make a quick and telling strike far behind enemy lines.

Still, Mosby’s men were very suspicious of Ames and most were convinced that he was a spy sent to lead them into a trap. Mosby, however, quickly put his trust in Ames and in doing so displayed a special skill about which his men often commented. He had, many felt, an extraordinary ability to meet a man and judge his character almost instantaneously. A short initial conversation with Mosby would result in immediate acceptance into or dismissal from the group. Mosby’s men said that he simply did not err in his judgment. Certainly, Mosby’s decision to accept Ames into his group of Partisans lends strong credence to the stories of this ability because Ames became one of the most trusted, respected and loyal members of Mosby’s command. In fact, prior to his being killed in a small skirmish in 1864, Ames was promoted to Lieutenant by Mosby.

Thus, on the night of March 8, 1863, Mosby and 29 men gathered in the small hamlet of Dover (just east of Middleburg, Virginia) and began riding in an easterly direction toward Union lines. It was a rainy and dark night. With the exception of Ames, Mosby had not told any of his men where they were going. Even in that early stage of Mosby’s exploits, however, the men followed willingly. They knew that when Mosby went out on a raid he had a good plan and that success would most likely be achieved.

The small band arrived in Fairfax City—many miles behind Union lines where Mosby and his men had thousands of enemy infantry, cavalry and artillery troops around them—without being detected. Mosby divided the group into even smaller elements each tasked with seizing prisoners and capturing horses. The prize was to be Percy Wyndham, but word quickly came to Mosby that Wyndham was spending the night in Washington City. Almost simultaneously, Mosby was informed that Union Brigadier General Edwin Stoughton was staying in town and he quickly adapted his plan to take advantage of this new piece of information.

Leading a few hand-picked men to the house where Stoughton was staying, Mosby gained access to the unlucky general’s bedroom, awoke him from a deep sleep by smacking him on the bare buttocks with his gauntlets and took him prisoner.

As Mosby was prodding Stoughton to dress quickly, other Rangers were continuing to move around Fairfax taking Union soldiers prisoner, capturing horses and then moving back toward the center of town. When the Rangers were once again gathered together, their entourage had been increased with the addition of 33 prisoners (including General Stoughton and two Union Captains) and 58 horses.

Departing town quickly—Mosby was determined to get back through enemy lines before dawn—the daring group of Rangers arrived in Warrenton, Virginia in the early afternoon to a hero’s welcome. In what still remains as one of history’s most extraordinarily daring military raids, Mosby’s men had not fired a single shot.

“President LINCOLN, when informed that Gen. STOUGHTON had been captured by the rebels at Fairfax, is reported to have said that he did not mind the loss of the Brigadier as much as he did the loss of the horses. "For," said he, "I can make a much better Brigadier in five minutes, but the horses cost a hundred and twenty-five dollars apiece."[9]

News of Mosby’s stealthy infiltration behind enemy lines and his capture of Stoughton flashed across the South and the North. Mosby became an idol for his countrymen, the shining exemplar of a dashing Southern Cavalier, while the citizens of the North began to see him as a bushwhacker, cutthroat and criminal. It was about this time that Northern mothers began tucking reluctant children into bed with the warning, “Hush, child, Mosby will get you.”[10]

The successful raid won a promotion for Mosby. On March 15, 1863 he was commissioned as a Captain.

The fame of Mosby’s small group grew as a result of the Fairfax Court House Raid and so, too, did its size. Almost every day, men began arriving in the area eventually known as “Mosby’s Confederacy” (Loudoun, Fauquier, Warren and Clarke Counties) seeking to join Mosby. Men who were too young (or in a few cases too old) to enlist in the Confederate Army, scarred veterans who had been discharged because of wounds but could still ride a horse and fire a pistol, officers who had resigned their commissions and men whose enlistments had expired made up the preponderance of Mosby’s recruits. In fact, the slow trickle of men permanently joining Mosby’s command continued to the very end of the war. By the time Mosby disbanded his command on April 21, 1865 in Salem (today’s Marshal), Virginia, over 800 men had mustered into the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry (the eventual designation of Mosby’s command). Throughout the 27 seven months that Mosby operated as a partisan, almost 2000 men (including the 800 mustered into the 43rd) spent a period of time with Mosby. Many of the men who came and went from the group were dismounted cavalrymen riding a raid looking for a re-mount, furloughed men seeking some adventure while home and detachments from other units operating near Mosby and his men. However, it was not until June of 1863 that the band of men being led by Mosby became anything more than an informal collection of raiders. Early on, the little group of men was sometimes referred to as “Mosby’s Conglomerates”.

A large percentage of the Rangers’ roster was comprised of very young men, boys in some cases, who were simply too young to enlist in the regular Confederate Army, but had a desire to fight. Charles E. Conrad was 14 when he joined the 43rd in 1864. Charlie Dear was 16 when he left the Virginia Military Institute in early 1863 to join the Rangers. Many more of the men were only 17, 18 or 19 when they sought out the command and mustered in. Mosby always felt that the many youths in his command were critical to its success. He felt that they always did what they were told to do and, even more importantly, they would fight.

With the constant infusion of new men, Mosby’s operational tempo increased. His continued success as a Partisan leader garnered him another quick promotion On March 26, 1863, he was promoted to Major. The promotion was an honor and recognition for Mosby’s skill, but it was the source of some controversy.

The promotion orders stated that as soon as practicable Mosby was to organize his informal command into a regular cavalry unit. In reality, the wording of the orders was an effort to protect Mosby as the Partisan Ranger Act had not proven to be successful and, in fact, the concept had fallen into disrepute. Many small units had been formed under the Act, but most were mere bands of undisciplined criminals and thieves. Men in the regular army envied the less rigid lifestyles of the partisans and many sought to join them. Their actions became a steady drain of manpower away from regular units. Senior Confederate officers neither liked nor supported the Act. Even Stuart urged Mosby to call his small band “Mosby’s Regulars”. Still, Mosby took exception to the directive. His desire was to lead a Partisan Ranger unit. He knew that the tenets of the Partisan Ranger Act, in particular allowing men to take and keep plunder, would be an important draw for filling his ranks. He also felt that leading a Partisan Ranger unit would allow him maximum flexibility in how, where and when he operated. He protested the wording of his promotion to General Stuart. Stuart forwarded Mosby’s concern to General Lee and Lee dismissed Mosby’s argument; Mosby was to lead a regular cavalry unit.

Mosby, a lawyer by trade and a man who, by nature, had difficulty backing down from a fight when he believed himself to be right, did not care for Lee’s response. And so, Mosby went over Lee’s head and presented his position to Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon. One truly must take a moment to contemplate the sheer audacity and effrontery of Mosby’s action. Less than three months earlier he had been a scout, with no formal rank, for General Stuart and now he was directly challenging a decision made by Robert E. Lee.

Fortunately for Mosby, Seddon had become aware of Mosby’s successes and overruled Lee’s decision; Mosby would continue to command Partisan Rangers. Mosby’s accomplishments for the remainder of the war proved that the stand he had taken was the correct one. The Partisan Ranger Act was officially repealed on February 17, 1864 and all Partisan Ranger commands were directed to report to the nearest regular unit where they would be mustered in as regular soldiers. However, two Partisan Ranger commands were permitted to retain their designation, “Mosby’s Rangers” and “McNeill’s Rangers”. Mosby would subsequently be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in February of 1864 and to Colonel on December 7, 1864.

By June of 1863, enough men had joined Mosby to warrant the forming of an official company. The metamorphosis of “Mosby’s Conglomerates” into the 43rd Battalion would commence with the forming of Company A. On June 10th, Mosby had all of the men report a few miles west of Middleburg to the small hamlet of Rector’s Crossroads (today’s Atoka) in order to activate the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry. The event would highlight another of Mosby’s “special” means of getting things done.

As a commander of a volunteer unit, Mosby was required to allow his men the opportunity to elect their officers and on June 10th, 1863, and as each new company of the 43rd was subsequently formed (Company H would be the last being formed on April 5, 1865), Mosby gave the men the chance to vote for a slate of candidates, picked solely by him.

Having known that he had enough men to form a company (nominal size of a regular cavalry company during the war was 100, but the 43rd Battalion’s companies were usually smaller), Mosby had been scrutinizing the actions of his men and had looked for those who had demonstrated extra courage and intelligence, earned the respect of the other men, and displayed a full understanding of how he, Mosby, operated. From those observations he had created a list of men to fill the positions of captain, first lieutenant, second lieutenant and third lieutenant. On the day Company A was to be formed, he gathered the men who would be assigned to the unit and informed them that they were to be its members. He then opened nominations for officers by reading his list, closed nominations without taking any from the men and asked for a vote. Any dissention amongst the voters was quickly squashed by Mosby informing them that they were welcome to leave the unit and join Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. There is no record of anyone making that choice. This same process was followed as each new company was formed.

Stories of Mosby’s ubiquity had been spreading within the ranks of Union cavalry. Of course, he was a man not blessed with supernatural powers, but by selecting men who would think, act and fight as he would, credence was given to the perception that he was often in several places at one time. As the number of companies in the 43rd increased, Mosby was able to confidently send out multiple patrols at any given time with the knowledge that they would be conducted as if he were personally commanding them.

Such power as wielded by Mosby in the appointment of his subordinate officers could have been abused, but Mosby seems to have never taken that path. Indeed, he had men in his command with whom he became close life-long friends, but his affinity for a man did not mean that he would be promoted ahead of those more capable of carrying out their duties. The Chapman brothers are an excellent example of Mosby’s selection of officers based on merit above all else. Sam Chapman was two years older than his brother William. Sam and Mosby became true friends during the war and continued their friendship after its conclusion – they corresponded with each other until Mosby’s death in 1916 (Sam died in 1919). Mosby was never as close to William, but it was William who would eventually be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the 43rd and assume the role of Mosby’s second in command. Sam only achieved the rank of Captain and commanded a company. Another Ranger, Fountain “Fount” Beattie, was a Private with Mosby in the Washington Mounted Rifles and was with Mosby from the very start of his partisan career. He and Mosby would remain very dear friends after the war. Nonetheless, “Fount” never rose higher than Lieutenant in the 43rd. Even Mosby’s younger brother, “Willie”, did not receive favored treatment. There can be little doubt that successfully accomplishing the mission, not friendship, cronyism or nepotism, is what drove Mosby in choosing his subalterns. Indeed, Mosby selected his subordinate officers based on merit and proven ability and then gave them his trust and confidence.

The manpower base from which Mosby was able to select his officers was superb. After the war, many of Mosby’s Rangers went on to become doctors, lawyers, ministers, politicians, law enforcement officers and civic leaders within their respective communities. At least three: Charles Edward Conrad, William George Conrad and Charles “Broadway” Rouss, became millionaires. Joseph Bryan became Editor and owner of The Richmond Times Dispatch and a distinguished member of Richmond society. Robert Stringfellow Walker founded The Woodberry Forest School in Orange, VA. John Cromwell Orrick, Jr. (later known as George Washington Arrington) became a tough, respected and legendary Captain in the Texas Rangers. The ability to achieve success in their post-war lives did not happen magically. The ambition, intelligence, courage and perseverance required to be productive as veterans after the war was most assuredly demonstrated repeatedly while they rode with Mosby.

When Mosby began operating in January of 1863, he had reported exclusively to General Stuart. That stream-lined chain of command would remain in place until Stuart died on May 12, 1864 from wounds received at Yellow Tavern. From that time until Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Mosby reported directly to General Lee. For all practical purposes, Mosby operated with no oversight. Stuart and then Lee would sometimes make requests for information regarding the location or activity of the enemy or suggest that Mosby direct increased activity against Union rail lines or the destruction of bridges, but Mosby was essentially free to decide his targets. He was far enough away from the main Confederate Army that his actions would not disrupt or conflict with any of Lee’s plans, but he was also close enough that his actions could, and did, draw Union forces away from confronting Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Not to be ignored, also, is the fact that Mosby and his men required little logistical support from the Confederate Army. For all practical purposes, the United States Government was both Quartermaster and Paymaster for the 43rd. Most Rangers came to own a string of dependable horses, quality tack for those same mounts, multiple Colt .44 revolvers and warm overcoats all through the reluctant “generosity” of Union soldiers. It was the rare Ranger who did not have at least a few Yankee greenbacks or gold coins in his pocket. About 80 Rangers participated in the famous Greenback Raid on October 14, 1864 near Duffield, West Virginia , where they seized a Union Army payroll of over $170,000 in greenbacks and subsequently divided the money amongst themselves. Each Ranger rode away from that raid with about $2,100.

Compared to other units, both Union and Confederate, the 43rd Battalion never suffered massive casualties in any single action during its twenty-seven months of existence. The lesser casualty rate stemmed from the fact that the fights in which the battalion was engaged were mere skirmishes when measured against the major battles of the Civil War. That is not to imply that the Rangers were never bloodied. Almost one hundred and twenty Rangers were killed in action, executed after being captured or died from wounds sustained in combat. At least one hundred more Rangers were wounded. Ranger Charlie Dear was wounded twelve times and Ned Hurst was wounded seven times. John Mosby was seriously wounded on three separate occasions. Additionally, he had at least one horse go down and roll over him. He also received a painful saber strike to the head and shoulder. More than four hundred and fifty Rangers were captured. Some of those captured were exchanged, released or paroled and usually returned immediately to the 43rd. About two hundred Rangers were transported to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor during the final months of the war and not released until the middle of June 1865.

Often, just thirty or forty Rangers using surprise, violence of action and superior firepower, would make an unexpected dash upon a startled Union cavalry patrol or wagon train. The frays would be short in duration with the Rangers attacking their enemy like a swarm of angry bees. Each Ranger selected an individual Union trooper as a target and closed for the kill. Often the group of Rangers would be outnumbered, but mounted on excellent horses and carrying multiple pistols—the Colt Army Model 1860 being the preferred weapon—they would slam into the enemy and simply overwhelm them with withering fire from their revolvers and the sheer impetuosity of their attack. The fights were up close and very personal; the combatants looked each other in the eyes as they plied their deadly trade.

The relentless nature of the Rangers operations continued until the end of the war. It was the Rangers’ constant threat of ambushing or attacking Union forces that made them so effective. Their activities could not be ignored by the Union commanders who were forced to take precautions, and deploy men and resources, to counter the omnipresent and recurring danger presented by Ranger sorties. Some part of the 43rd was actively on patrol almost every day, seeking to gather information on the enemy, riding out to find and engage Union patrols or proceeding out on a mission to attack a specific target. To those more familiar with the history of Mosby’s Rangers, such fights as Miskel’s Farm, Catlett Station, Warrenton Junction, Grapewood, Loudoun Heights, Mount Zion, Mount Carmel and Arundel’s Tavern are well known. They were all relatively small scale actions with rarely more than one hundred Rangers engaged in the encounter. The largest group of Rangers ever gathered for one mission, about 350, conducted the Berryville Wagon Train Raid on August 13, 1864 near Berryville, Virginia . Interspersed amongst the “larger” fights were countless smaller clashes that required Union soldiers to remain vigilant and kept them scared, nervous and worried. Northern cavalry venturing into “Mosby’s Confederacy” could not relax while they were there. Herman Melville, perhaps best known for writing Moby Dick, captured the mood of the Union soldiers and the mystique of Mosby (and his command) when he wrote these lines in his poem The Scout Toward Aldie: “But Mosby’s men are there / Of Mosby best beware” and “As glides in seas the shark / Rides Mosby through green dark”.[11]

Unfortunately for the Confederacy, the frequent successes of Mosby’s Rangers occurred at the tactical level. Although they compelled the Union to deploy thousands of troops to actively hunt for them or to establish manned defenses with which to protect themselves, the Rangers did not have a great impact on the war at the strategic level. They would not, could not, stop what seemed to become more inevitable as 1864 became 1865.

A day or two after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, Mosby became aware of the heartbreaking news. After a series of small dramas and parlays between Mosby and Union commanders to determine the terms of surrender for the Rangers, Mosby called his men together on April 21 in the town of Salem, Virginia (today’s Marshall). Mosby once more displayed a glimpse of his combative personality and fierce personal pride by deciding to disband the 43rd rather than surrender it to the enemy. His final words to the men who had served him so valiantly were:

“Soldiers! I have summoned you together for the last time. The vision we cherished of a free & independent country has vanished and that country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to our surrendering it to our enemies. I am no longer your commander. After an association of more than two eventful years, I part from you with a just pride in the fame of your achievements & grateful recollections of your generous kindness to myself. And now, at this moment of bidding you a final adieu, accept this assurance of my unchanging confidence & regard. Farewell!”[12]

John Singleton Mosby

| Born | December 6, 1833 in Powhatan County, Virginia |

| Died | May 30, 1916, Washington D.C. |

| Buried | Warrenton Cemetery, Warrenton, Virginia |

| Father | Alfred Daniel Mosby |

| Mother | Virginia (McLaurine) Mosby |

| Career Milestones | 1861 joined the Washington Mounted Rifles as a private | 1861 promoted to first lieutenant with the 1st Virginia Cavalry| 1861 joined JEB Stuart’s staff as a private and scout | 1862 captured and exchanged | 1863 begins his career as a ranger with a force of 9 men operating behind Union lines | 1863 promoted to captain | 1863 promoted to major | 1863 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry officially formed | 1864 promoted to lieutenant colonel | 1864 promoted to colonel | 1865 disbands the 43rd Battalion rather than surrender it shortly after Appomattox| 1868 worked to elect Grant president | 1878-1885 appointed US Consul to Hong Kong | 1992 Mosby was a member of the first group of men honored with induction into the United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame. |

- [1] Hugh C. Keen & Horace Mewborn, 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby's Command (Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1993), 11.

- [2] In 1992, Colonel John Singleton Mosby was a member of the first group of men honored with induction into the United States Army Ranger Hall of Fame. The inductees included men whose names will forever be etched in Ranger legacy: Major Robert Rogers who formed and commanded “Rogers’ Rangers” during the French and Indian War; Brigadier General William Orlando Darby who organized, trained and subsequently commanded the 1st Ranger Battalion (which represented the return of Ranger-designated units in the U.S. Army) during World War II; Major General James Earl Rudder who commanded the 2nd Ranger Battalion when it scaled the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc on June 6, 1944 on D-Day; and Major General Frank Dow Merrill who commanded the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) better known as “Merrill’s Marauders”. The remarkably distinguished group of men also included three recipients of the Medal of Honor: Specialist Four Robert D. Hall, Staff Sergeant Robert J. Pruden and Staff Sergeant Laszlo Rabel; http://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/rtb/rhof/index.html. Mosby’s biographical information which can be seen on the Ranger Training Brigade Ranger Hall of Fame web site and on the framed small portrait of Mosby, with accompanying biographical information, on display at the Ranger Hall of Fame in Ft. Benning, GA.

- [3]John Singleton Mosby, The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1917), 21.

- [4] James M. Matthews, ed., Statutes at Large of the Confederate States of America Commencing with the First Session of the First Congress 1862 (Richmond, VA: R.M. Smith Printer to Congress, 1862),48.

- [5] Shelby Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perryville ( New York: Random House, 1958), 529.

- [6] Mosby, Memoirs, 124-5.

- [7] Mosby, Memoirs, 149-150.

- [8] Mosby, Memoirs, 151.

- [9] New York Times, March 11, 1863.

- [10]James Ramage, Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singleton Mosby (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 5.

- [11] Herman Melville, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of War (New York: Harper, 1866).

- [12] Mosby, Memoirs, 360-1.

If you can read only one book:

Keen, Hugh C.and Horace Mewborn. 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby’s Command. Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1993.

Books:

Alexander, John H. The Mosby Myth: A Confederate Hero in Life and Legend. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

Ashdown, Paul and Edward Caudill. The Mosby Myth: A Confederate Hero in Life and Legend. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

Black, Robert W. Ghost, Thunderbolt, and Wizard: Mosby, Morgan and Forest in the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008.

Bonan, Gordon B. The Edge of Mosby’s Sword: The Life of Confederate Colonel William Henry Chapman. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Brown, Peter A. Take Sides with the Truth: The Postwar Letters of John Singleton Mosby to Samuel F. Chapman. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Buckland, Eric W. Mosby’s Rangers: Colts & Courage. Privately printed, 2021.

———. Mosby’s Rangers: A Legacy of Success. Privately printed, 2020.

———. They Rode With Mosby: Stories of Colonel John S. Mosby’s Most Daring Rangers. Privately Printed, 2018.

———. From Rockbridge to Loudoun: “Mosby’s Keydet Rangers.” Privately printed, 2018.

Crawford, J. Marshall. Mosby and His Men. New York: G.W. Carleton, 1867.

Evans, Tom & Jim Moyer. Mosby Vignettes: Volumes 1-5. Privately printed, 1993.

———. Mosby's Confederacy: a guide to the roads and sites of Colonel John Singleton Mosby. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1991.

Goetz, David. Hell is being Republican in Virginia: The Post-War Relationship between John Singleton Mosby and Ulysses S. Grant. Bloomington, IN: Privately printed by Xlibris, 2012.

Hakenson, Donald C. and Gregg Dudding. Mosby Vignettes. Vols. 6 & 7. Privately printed, 2002.

Hakenson, Donald C. and Charles V. Mauro. A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby's Combat Operations in Fauquier County, Virginia. HMS Productions, 2019.

———. A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby's Combat Operations in Fairfax County, Virginia. HMS Productions, 2013.

———. A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby's Combat Operations in Loudoun County, Virginia. HMS Productions, 2016.

Hughes, V. P. A Thousand Points of Truth: The History and Humanity of COL. John Singleton Mosby in Newsprint. Bloomington, IN: Privately printed by Xlibris, 2016.

Jones, Virgil Carrington. Ranger Mosby. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944.

Lawrence, Lee. Society of Rebels: Diary of Amanda Edmonds, Northern Virginia 1857-1867. Warrenton, VA: Piedmont Press & Graphics, 2017.

Mewborn, Horace. “From Mosby’s Command”: Newspaper Letters & Articles by and about John S. Mosby and His Rangers. Baltimore: Butternut & Blue, 2005.

Mitchell, Adele H. The Letters of John S. Mosby. Leesburg, VA: Stuart-Mosby Historical Society, 1986.

Mosby, John S. The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby. Boston: Little, Brown, 1917.

———. Mosby’s War Reminiscences and Stuart’s Cavalry Campaign. Boston: Geo. A. Jones, 1887.

Munson, John W. Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla. New York: Moffat, Yard, 1906.

Ramage, James A. Gray Ghost: The Life of Col. John Singleton Mosby. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999.

Scott, John. Partisan Life with Col. John S. Mosby. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1867.

Siepel, Kevin H. Rebel: The Life and Times of John Singleton Mosby. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983.

Wert, Jeffry D. Mosby's Rangers: From the High Tide of the Confederacy to the Last Days at Appomattox, the Story of the Most Famous Command of the Civil War and Its Legendary Leader, John S. Mosby. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Williamson, James J. "Mosby's Rangers: A Record of the Operations of the Forty-third Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, from its Organization to the Surrender. New York: Sturgis and Walton, 1909.

Organizations:

The Stuart-Mosby Historical Society

The Stuart-Mosby Historical Society is a non-profit organization established to research and preserve accurate history and to perpetuate the memory and deeds of General J. E. B. Stuart and Colonel John S. Mosby. Perhaps the best description of the goals of the Society is given in the mission statement:To promote the study of the lives and military accomplishments of General J. E. B. Stuart and Colonel John S. Mosby. To share our knowledge of these officers with others through publications, talks, and appropriate ceremonies whenever and wherever possible. To honor General Stuart and Colonel Mosby annually on the anniversaries of their births. To preserve, promote and provide an accurate understanding of the history of Confederate arms, particularly the mounted arm. To secure, when possible, important artifacts that can be directly associated with General Stuart and Colonel Mosby. To ensure that the collected artifacts of the Society are preserved and held in a safe place that is accessible to members of the Society and reputable scholars. To work through all possible avenues to ensure that monuments, markers, artifacts, and public presentations on all aspects of Confederate history and arms are maintained and held in honor. To promote communication between members of the Society. To maintain a viable and active membership in the Society that is in full agreement with the above objectives.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Mosby’s Confederacy Tours

Author and tour guide David Goetz offers three different tours visiting important sites in “Mosby’s Confederacy”.