Jubal Early's 1864 Raid on Washington

by David P. Hopkins, Jr.

While often recognized as a leading advocate for the Lost Cause during Reconstruction and having a storied Civil War career fighting for the Confederacy, Jubal Early is best known for his 1864 Valley Campaign and his raid on Washington, D.C. Pinned down at Petersburg by Union General Ulysses S. Grant, Lee decided to send Early’s corps into the Shenandoah Valley, hoping that Grant would give chase, relieving some of the pressure on Lee’s army. Neither Lee nor Early had any idea how close the Confederates would come to the Northern capital or how much fear and panic they could unleash in Washington City. Additional objectives included the liberation of a number of Confederate prisoners of war held in various camps in and around Washington, disrupting Union rail traffic, clearing the Valley of destructive Federals, as well as changing the perception of the war’s direction by attacking the White House. Leaving the Richmond area on June 13, 1864, Early moved west and on June 18 defeated Union General David Hunter at Lynchburg. From there Early moved swiftly to the outskirts of Washington sending citizens there and in other communities into a panic. On the way to Washington Early demanded ransoms from towns like Hagerstown and Frederick. On July 9, Early defeated Union General Lew Wallace at Monocacy but the battle delayed his advance and sapped his strength. As Early approached Washington Grant sent two divisions from the Richmond area to reinforce the forts guarding the city. On July 11-12 Early’s troops attacked Fort Stevens, a major fort in the chain protecting Washington. The fighting was mainly skirmishing with about 300 casualties on both sides. During the sporadic fighting at Fort Stevens, President Lincoln decided that he would come to Fort Stevens to see the fighting for himself. Famously, the president stood on the fort’s parapet to watch the action when a Union soldier next to him was shot by a rebel sharpshooter. As historian Marc Leepson has noted about the incident, “That marked the first—and only – time in American history that a sitting U.S. president came under hostile fire in a military engagement.” Following the battle at Fort Stevens, Early continued his Valley Campaign with little success. Withdrawing to the lower Shenandoah Valley, Early continued to harass Union operations, but he never again posed the threat like the one in the summer of 1864. Defeated at Strasbourg in the fall, Early was forced to retreat from the Valley, allowing Sheridan and his men to ensure that this region would not feed Confederate troops for the rest of the war. The campaign and raid bought time for the Confederacy and the Shenandoah Valley, the breadbasket of the Confederacy, in time for the 1864 fall harvest allowing needed supplies to reach Lee in Richmond. The raid also had an international impact in that it demonstrated to European nations and England that the Confederate army was still a formidable fighting force. This late in the war, however, any hope for international recognition for the Confederacy was gone as was any hope of winning the war. After the war, through a number of lectures, articles, and books, Early became a leading Lost Cause warrior. It was in this post-war crusade that Early was especially tough on General James Longstreet, stressed the Confederate army’s lack of manpower—called Grant a “butcher”, accused a number of Union veterans of not telling the real story of the war, and depicted Robert E. Lee as a Confederate hero—major elements of the Lost Cause narrative.

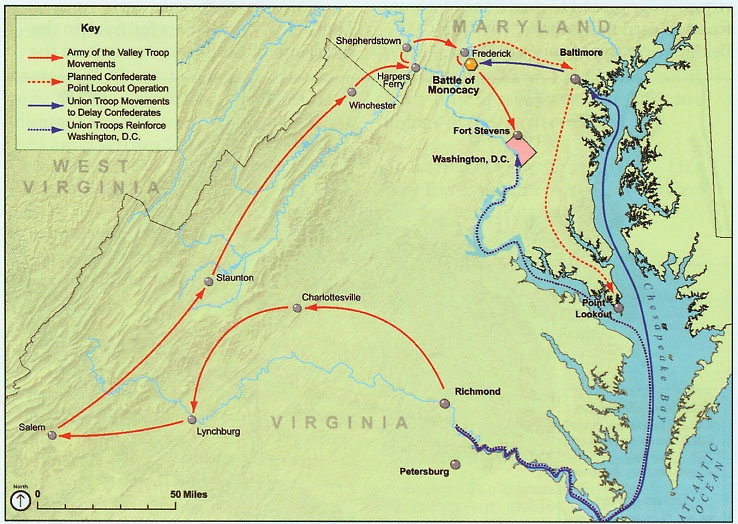

General Early and the Army of the Valley Movements Map

Map Courtesy of: Thomas’ Legion: The 69th Carolina Regiment at http://www.thomaslegion.net/battleoffortstevensandwashingtondc.html

While often recognized as a leading advocate for the Lost Cause during Reconstruction and having a storied Civil War career fighting for the Confederacy, arguably, Jubal Early is best known for his 1864 Valley Campaign and raid on Washington, D.C. Jubal Anderson Early enjoyed a storied career before the Civil War. He graduated 18th in his class at the United States Military Academy, fought Native Americans in Florida, became a lawyer, served in the Mexican War, and served in the Virginia House of Delegates. As secession debates raged across the South in 1860 and 1861, Americans quarreled over the future of slavery in the republic. As a conservative Whig and a strong supporter of slavery, Early steadfastly opposed secession, voting against it in the Virginia House in the spring of 1861. However, once his home state left the Union in May 1861, Early joined the 24th Virginia as a colonel and fought in many of the war’s early engagements including First Manassas, the Seven Days Battles, Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Early also served at Gettysburg and Salem Church following his promotion to major general in January of 1863. By 1864, with the Confederacy hoping to stave off defeat and fight through the presidential election in the fall, a push had to be made by the Confederate army if they hoped for any chance at independence. If the Confederate army could string together a series of victories (or not suffer any major defeats), perhaps it might push Northerners to seek some kind of peace by preventing Abraham Lincoln’s reelection in November and electing a peace candidate as President. This was the Confederacy’s last, best hope for independence. It is in this context that during the summer of 1864, (now Lieutenant General) Early embarked on a raid into the North that created quite a stir among those who lived in and around the capital. While Early ultimately failed in his attempt to swing public opinion against Lincoln or the Union war effort, his raid sent panic throughout the North and prolonged the war.

For most Americans today, an attempt to take Washington, D.C. in a military sense appears to be, at best, an exercise in futility. At the start of the Civil War in April 1861, this was not the case. After all, the British had taken and burned the capital, with very little resistance, during the War of 1812. Certainly, Jubal Early was familiar with the events little more than fifty years earlier as he drafted his plan for what has been a called a third invasion of the North. When the war started, there were few protective forts guarding the city. This changed with the Union defeat at First Manassas (Bull Run) on July 21, 1861. The fighting at Manassas occurred a mere 25 miles from the capital city and, consequently, the Lincoln Administration constructed 68 forts in a 37-mile circle around Washington during the months following the battle. With General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia suffering heavy losses during the Overland Campaign in the spring of 1864, something had to be done to loosen the Federal grip on Lee’s forces near Richmond. As long as this situation remained unchanged, Union victory was imminent. Following the death of Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson at Chancellorsville, Lee had come to rely on Early, who he called his “bad old man.” Pinned down at Petersburg by Union General Ulysses S. Grant, Lee decided to send Early’s corps into the Shenandoah Valley, hoping that Grant would give chase, relieving some of the pressure on Lee’s army. Neither Lee nor Early had any idea how close the Confederates would come to the Northern capital or how much fear and panic they could unleash in Washington City.

Early on the morning of June 13, 1864, Early and his men, left the Richmond area and headed west commencing his 1864 Valley Campaign. The goal of Early’s Valley Campaign was to both interfere with Grant’s plans by forcing the Union commander to send troops to frustrate Early’s efforts while at the same time relieving General Lee who was positioned in defense of Richmond. Many of Early’s men had served, both officers and regular troops, under General Jackson until his death in May of 1863. On the number and condition of the soldiers who would make Early’s raid, historians have noted that he lacked both enough men and good men, though he had enough capable subordinate officers to make the raid. [1] Early’s troops, three divisions of about 10,000 men and 4,000 cavalrymen, left Richmond with visions of victory and turning the tide of the war in favor of the Confederacy. Accomplishing smaller goals as a part of the raid, however, could prove fruitful in keeping Confederate hopes alive. These smaller goals included the liberation of a number of Confederate prisoners of war held in various camps in and around Washington, disrupting Union rail traffic, clearing the Valley of destructive Federals, as well as changing the perception of the war’s direction by attacking the White House. Perhaps most important for Lee was, quite simply, forcing Grant to send reinforcements north to head off Early. If Early could be successful here, this might relieve some of the pressure from Lee’s army as well as ease some of the pressure placed on Richmond by Grant’s Overland Campaign. Early, extremely devoted to Lee, very eagerly moved west from Richmond and defeated Union Major General David Hunter at Lynchburg on June 18, crossed the Potomac River and made his way north into Maryland by July 5. Early moved swiftly and quietly to the outskirts of D.C. sending citizens there—and communities as far north as Baltimore—into a panic.

It was not the simple presence of Early and his Confederate troops, but their actions as they moved north caused that panic. Early wreaked havoc in Maryland communities during his raid. Immediately after crossing the Potomac, Brigadier General John McCausland, who served under Early, moved on Hagerstown and demanded ransom from the town if it hoped to remain intact. On July 6, McCausland demanded $20,000 in United States currency and various articles of clothing for his men, including shirts, socks, boots, hats, etc. In an effort to preserve the town, a local banker raised the necessary cash, though other arrangements had to be made in lieu of the articles of clothing, as procuring such articles in a time of war proved to be difficult. A few days later, on July 7, nervous Frederick citizens saw Early’s men enter the town. Like Hagerstown, Frederick received a two ransom notes from the Confederate army. The first requested “500 barrels of flour, 6,000 pounds of sugar, 3,000 pounds of coffee, 20,000 pounds of bacon, and 3,000 pounds of salt.” [2] A second note demanded $200,000 cash in United States currency. If these demands were not met, Early promised to burn Frederick to the ground. Both local bankers and the mayor, William G. Cole, produced the ransom and the town was spared. “Frederick officials borrowed the money from five local banks,” notes a New York Times article reminiscing of the raid, “which financed the loan with bond issues, the last payment being made on Oct. 1, 1951. Senator Charles McCurdy Mathias of Maryland estimated that the $200,000-plus interest compounded annually since 1864 at 4 percent amounted to almost $14 million, but he never succeeded in persuading Congress that the Government was obligated to reimburse Frederick ‘for value received by the Union.’”[3]In addition to looting these communities, Early’s men burned down the governor’s mansion, raided prominent Republican politician Francis Preston Blair’s wine cellar, and burned the Silver Spring home of Blair’s son and Postmaster General, Montgomery Blair. [4]

Despite all of the chaos and fear produced as Early approached the outskirts of the capital city, the entire success of the raid depended upon the speed of Early’s Confederate troops. This was made clear when Early clashed with Union Major General Lewis “Lew” Wallace (author of Ben Hur) at Monocacy, small railroad junction four miles south of Frederick. Here, Wallace and his 2,800 men took up defensive positions at this “vital crossroads where the National Pike led the Baltimore and the Georgetown Pike to Washington.” [5] The delay would be critical. On July 9, Early, who outnumbered Wallace and had a more proven fighting force, fought the Federals in an intense day-long battle. Both sides suffered heavy casualties with about 1,300 Union dead and as many as 800 Confederate casualties. As a result, the defeated Wallace retreated north to Baltimore while Early rested his men in the field. This battle, though a victory, would be enough to sap Early’s strength and enough of a delay to allow Federal reinforcement of the various forts around Washington.

Early’s raid continued the next day, July 10, when he continued towards the capital along the Georgetown Pike. The hard fighting at Monocacy combined with the intense July heat made the march toward Washington an extremely difficult one. Early’s soldiers were exhausted. The Federals’ quick reinforcement of nearby forts and an influx of volunteers made the task more difficult for Early’s tired troops. Early moved from Rockville and pushed into Gaithersburg, only a few miles from the capital city, and battled with Union pickets before moving on to Silver Spring (where he punished the Blairs as noted above). The key Federal defenses were at Forts Reno and Stevens, and early attacked Fort Stevens over the next few days. It was at this point that General Grant decided to send two of Major General Horatio Gouverneur Wright’s divisions from the outskirts of Richmond to City Point, Virginia, and, from there, to Washington to help with the defense of the city. These divisions reinforced Fort Stevens.

The end of Jubal Early’s northern raid would come at Fort Stevens on July 11-12, 1864, when he ultimately decided to stay and attack, he hoped, before Grant’s reinforcements arrived. What followed was nearly two full days of skirmishing between Early’s Confederates and Federals who manned the fort with approximately 300 casualties on the Union side and the same number, if not more, for the Confederates. During the sporadic fighting at Fort Stevens, president Lincoln decided that he would come to Fort Stevens to see the fighting for himself. Famously, the president stood on the fort’s parapet to watch the action when a Union soldier next to him was shot by a rebel sharpshooter. As historian Marc Leepson has noted about the incident, “That marked the first—and only – time in American history that a sitting U.S. president came under hostile fire in a military engagement.” The president quickly withdrew to a safe location. Grant’s reinforcements combined with the exhaustion of the Confederates proved to be too much for Early at Fort Stevens and he withdrew on the evening of July 12, thus ending his raid on Washington, D.C.

Following the battle at Fort Stevens, Early continued his Valley Campaign with little success. Withdrawing to the lower Shenandoah Valley, Early continued to harass Union operations, but he never again posed the threat like the one in the summer of 1864. By the fall, the new Union commander in the Valley, General Philip Henry Sheridan, chased Early to Strasburg. By October, with Early’s army recovered from the defeats of the summer and early fall, he mounted one last attack against Sheridan at Strasburg. Another defeat, Early was forced to retreat from the Valley, allowing Sheridan and his men to ensure that this region would not feed Confederate troops for the rest of the war.[6]

While not successful in capturing Washington, Early’s raid bought time for the Confederacy in that it did prolong the war by weeks, maybe many months. However, it was too little, too late in that the war would be over in earnest by early April of 1865. The raid and the Valley Campaign it was part of also secured the Shenandoah Valley, the breadbasket of the Confederacy, in time for the 1864 fall harvest. This would allow much needed food and supplies to reach Lee’s army, still besieged by Grant outside of Richmond. Adding to these supplies from the Valley, were a number—thousands—of horses and cattle captured throughout Maryland during the raid that the Confederate army so badly needed. The raid also had an international impact in that it demonstrated to European nations, England in particular, that the Confederate army was still a formidable fighting force. This late in the war, however, any hope for international recognition for the Confederacy was gone as was any hope of winning the war.

Following Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, Early was sent to fight in the Trans-Mississippi West. With the conclusion of the fighting between the armies in North Carolina and, later, Texas, during the late spring and summer of 1865, Early fled to Cuba and from there to Canada where he remained until 1869. Upon his return to reunified United States, Early made sure that his version of events made their way into the history of the war. Through a number of lectures, articles, and books, Early became “a leading Lost Cause warrior.” [7] It was in this post-war crusade that Early was especially tough on General James Longstreet, stressed the Confederate army’s lack of manpower—called Grant a “butcher”, accused many Union veterans of not telling the real story of the war, and depicted Robert E. Lee as a Confederate hero—major elements of the Lost Cause narrative. Jubal Early was quick to realize that, to use the words of Walt Whitman, “the real war will never get in the books,” and, subsequently with his Lost Cause narrative, pushed to see that this statement rang true for later generations. [8]

- [1] See Charles C. Osborne, “Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington,” in Robert Cowley, ed. With My Face to the Enemy: Perspectives on the Civil War (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2001), 445-6.

- [2] http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2010-02-07/news/bal-md.backstory07feb07_1_frederick-fresh-troops-rebel , accessed January 30, 2017.

- [3] http://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/05/travel/a-masterpiece-in-maryland.html?pagewanted=all&pagewanted=print , accessed January 30, 2017.

- [4] See also, James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 756-8. Following the failure of the Washington raid, Early attempted to exact a ransom on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in retaliation for General Hunter’s authorization of the looting and burning of Shenandoah Valley communities earlier in the summer of 1864. Early demanded $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in Greenbacks to compensate those in the Valley who suffered at the hands of Hunter’s men. Unlike Hagerstown and Frederick, Chambersburg refused to pay the ransom and, as a result, a portion of the town was burned on Early’s July 30 orders.

- [5] Marc Leepson, “The Great Rebel Raid,” in Civil War Times 46, no. 6 (August 2007): 24.

- [6] See Steven E. Woodworth, This Great Struggle: America’s Civil War (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., 2011), 306-10.

- [7] Gary W. Gallagher, Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy in Frank L. Klement Lectures (Marquette: Marquette University Press, 1995), 6.

- [8] Walt Whitman, Specimen Days & Collect (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1883), 80–81

If you can read only one book:

Cooling, Benjamín Franklin. Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington 1864. Baltimore, MD: Nautical & Aviation Publishing, 1989.

Books:

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Jubal Early: Robert E. Lee’s Bad Old Man. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), 51-92.

Donald, David Herbert et al. With My Face to the Enemy: Perspectives on the Civil War. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2001, 553-8.

Leepson, Marc. “The Great Rebel Raid,” in Civil War Times 46, no. 6 (August 2007): 24-29.

Osborne, Charles C. Jubal: The Life and Times of General Jubal A. Early, CSA, Defender of the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 1992.

McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, 756-8.

Woodworth, Steven E. This Great Struggle: America’s Civil War. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011, 264-70.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This is the Civil War Trust page on Early and his raid.

Steven Vogel, “For Gen. Jubal Early. a raid north nearly led to the capture of Washington,” in Washington Post, April 26, 2014.

This is the Civil War Trust page on Washington D.C.’s Civil War defenses, critical in Early’s raid.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.