Richmond: Capital of the Confederacy

by Mary A. DeCredico

The Virginia Secession Convention had voted against secession on April 4, 1861, however, with the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s subsequent call on April 15 for 75,000 ninety-day volunteers to “crush the rebellion,” by a vote of 88 to 55 the Convention took Virginia out of the Union on April 17, 1861. While the first Confederate capital was in Montgomery AL, Richmond was Confederacy’s most industrial city and Virginia was the largest Confederate state, so Richmond was chosen as the permanent capital for the Confederacy. Richmond’s population in 1860 was 38,000 including 11,700 slaves. By 1864 it had swelled to between 100,000 and 130,000 inhabitants. With the constant influx of soldiers, visitors and other newcomers flocking to the city, Richmond’s economy was stretched. Lodging, food and other necessities of life quickly disappeared. The initial prosperity that the relocated Confederate capital brought soon was accompanied by a crime wave, the establishment of houses of prostitution and gambling haunts. After the Battle of First Bull Run Richmond did not contain enough hospitals to take care of the 1,600 Confederate wounded as well as the 1,400 Union prisoners of war. Locals opened their doors to tend to the wounded. By the end of the war, the Chimborazo Hospital would care for almost 70,000 patients with a mortality rate under ten percent and Richmond became the hospital center of the Confederacy. As the war progressed, Richmond suffered from food shortages and massively inflating prices. The battles of Second Manassas and Antietam added to the already overcrowded and strained hospital system as thousands of wounded and captured men streamed into the Confederate capital as did the subsequent Battle of Fredericksburg. In March 1863, an explosion at the Brown’s Island munitions facility killed and injured many young girls working there. On April 2, 1863, the Richmond Bread Riot occurred as women concerned about the good prices looted stores. After the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, the Richmond Capitol building was used for Stonewall’s Jackson’s lying in state. The winter of 1863-1864 saw further food shortages, price increases as Confederate money became increasingly worthless and a rise in robberies especially of food. During the battles in 1864 in the Overland Campaign Robert E. Lee foresaw the eventual loss of Richmond through siege if he could not stop Grant. The Petersburg-Richmond Campaign was fought from June 1864 to March 1865. On April 2, 1865 Lee faced the inevitable and evacuated Richmond. After four long years of war, the proud capital stood on the brink of self-inflicted destruction.

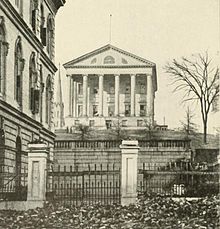

Damaged Richmond Capitol Building in April 1865 After the City’s Capture by Union Forces.

Photograph from: Francis T. Miller and Robert S. Lanier, eds. The Photographic History of the Civil War, 10 vols. (New York: Review of Reviews, 1911), 303.

In response to the election of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1860, the Convention of the People of South Carolina meeting in Columbia on December 17, 1860 voted unanimously to secede. The Palmetto state was followed by six other states of the Deep South. In the upper South, however, secession was voted down. Virginia was an especially pivotal state because of its size, its industries and its political prestige.

Virginians in general and residents of the state capital, Richmond, followed a tortured path to secession. The city and state had strong commercial ties with other states of the upper South and with the North. The Virginia Secession Convention had voted against secession on April 4, 1861 because the state’s political leaders did not believe Lincoln’s election alone posed a sufficient threat. However, with the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s subsequent call on April 15 for 75,000 ninety-day volunteers to “crush the rebellion,” by a vote of 88 to 55 the Convention took Virginia out of the Union on April 17, 1861. [1]

While the secession convention was deliberating, the Confederate government in Montgomery, Alabama, dispatched Vice President Alexander Stephens to monitor the debates and to put pressure on the delegates to vote in favor of secession. Stephens and other government officials in Montgomery were not oblivious to the advantages Richmond possessed. Richmond would be the nascent Confederacy’s most industrial city and Virginia would be the largest Confederate state. Stephens exhorted Virginians to join the Confederacy since “The enemy is now on your border.” He also hinted that Richmond could become the new capital of the Confederacy: “There is no permanent location in Montgomery—and should Virginia. … become the theatre of the war, the whole [government] may be transferred here.” The Virginia Secession Convention then voted to form a temporary alliance with the Confederacy. Delegates had to move somewhat cautiously for they had promised to hold a popular referendum vote on secession. That election was scheduled for May 23, 1861. [2]

It did not take long for city fathers to act on Stephens’s comments: shortly thereafter, the Virginia Convention extended an invitation to President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate States government “to make the city of Richmond . . . the Seat of the Government of the Confederacy.” Consequently, the Confederate government passed a resolution “to hold their session in July in this City and to make it the seat of the Government of the Confederacy.” As soon as the popular referendum on secession passed, the path was clear for the Confederate government move from Montgomery to the Virginia State capital. Despite discussion and debate by contemporaries then and historians since, the decision to relocate the Confederate capital from Montgomery to Richmond was a sound one, notwithstanding its proximity to the Federal capital in Washington, D.C. The city by James bore the mantle of the Founding Fathers: Patrick Henry had demanded liberty at St. John’s church and Thomas Jefferson had designed the capitol building. The city housed many industries that would be essential to the Confederate war effort, including the Tredegar Iron Works, one of only two such facilities in the entire South. Richmond had to be defended whether it was the capital or not. Hence, trains began arriving at Richmond’s train depots carrying the members of the government and their staffs. [3]

Richmond’s population in 1860 was 38,000 including 11,700 slaves. But that number swelled as people flocked to Richmond seeking government jobs. The influx of new visitors amused and stunned many locals. Thomas Cooper DeLeon who lived in both Montgomery and Richmond described his first impression of the city:

passing out of the cut, through the high bluff, just across the ‘Jeems’ River bridge, Richmond burst beautifully into view, spreading panorama-like over her swelling hills, with the evening sun gilding simple houses and towering spires alike into glory. The city follows the curve of the river, seated on amphitheatric hills, retreating from its banks; fringes if dense woods shading their slopes, or making blue background against the sky. No city of the South has a grander or more picturesque approach. [4]

The Richmond Daily Dispatch observed,

The Confederate Government is in Richmond. It has come to make its home with us during our struggle with the North. It could not bear the discomfort of living so remote as Montgomery from the seat of danger and the theatre of the campaign. It could not brook the idea of being itself secure, while Virginia was in danger. It desired to meet the enemy face to face…Virginia welcomes it with outstretched arms and swelling hearts. [5]

Not everyone in Virginia’s capital city was as excited as the editors of the Richmond Daily Dispatch. DeLeon noted that many old time residents of the capital began to feel “as much as the Roman patricians might have felt at the impending advent of the leading families of the Goths.” He went on to add, “The flotsam and jetsam that had washed from Washington to Montgomery followed the hegira to Richmond … and sent cold chills down the sensitive Virginia spine.” Even First Lady Varina Davis noticed a “certain offishness.” As much as the Davises tried to break the ice of Richmond society, they never really did.[6]

As more troops arrived to organize and drill, Richmond took on the character of one vast army camp. One of the most popular activities for locals and visitors was to gather at the city’s various encampments to watch the citizen soldiers drill. Optimism was high and most believed the war would be a short and the victory glorious.

With the constant influx of soldiers, visitors and other newcomers flocking to the city, Richmond’s economy was stretched. Lodging, food and other necessities of life quickly disappeared. The initial prosperity that the relocated Confederate capital brought soon was accompanied by a crime wave, the establishment of houses of prostitution and gambling haunts. Juvenile delinquency also increased as gangs of young boys fought to establish their ownership of certain segments of the city. These problems never fully went away and would remain a constant as long as the Confederate capital remained in Richmond.

The first of many “On to Richmond” campaigns took place on June 10, 1861. Major General Benjamin Butler advanced up the peninsula between the York and James Rivers from Fort Monroe intending to attack Richmond from the east. His force was defeated at the Battle of Big Bethel. Richmonders and other Southerners rejoiced in this first land victory, but that victory would only produce more over confidence on the part of the people.

A more dangerous threat loomed to the north. Confederate forces located near Manassas, Virginia, were threatened by a force of 35,000 Federal troops under the command of Major General Irvin McDowell. Although McDowell protested to President Lincoln that his troops were too green to take on the Confederates under General P. G. T. Beauregard, Lincoln insisted he attack; the Federal 90-day enlistments were due to expire.

The Battle of First Bull Run (First Manassas) was a battle in name only: it consisted of two green armies that resembled more a mob than effective fighting units. Late on the afternoon of July 21, 1861, the Confederates gained the upper hand. The Federal lines finally broke and a steady retreat became an all-out rout. Civilians who had ridden out to watch were soon caught up in the flight to avoid the pursuing Confederates.

News of the great victory over the Northern army was, according to one local woman, received “calmly.” But on July 22 that calmness was replaced by shock and horror at the sight of the wounded. City resident Sallie Putnam noted that Richmond did not contain enough hospitals to take care of the 1,600 Confederate wounded as well as the 1,400 Union prisoners of war. Locals opened their doors to tend to the wounded, but it would take the Confederate government to centralize the hospital system. By the end of the war, the Chimborazo Hospital would care for almost 70,000 patients with a mortality rate under ten percent. Indeed, Richmond would become the hospital center of the Confederacy. [7]

Summer turned to fall and early winter, but the victory at Manassas was not duplicated for months. Although the Virginia front was quiet, the Confederacy suffered serious reverses along the Atlantic coast at Roanoke Island and Hatteras Inlet, and out west in middle Tennessee. A cold, steady rain fell on the Confederate capital as Jefferson Davis was sworn in as permanent president on February 22, 1862. He acknowledged the challenges the young nation faced, but urged his listeners to live up to their Revolutionary forbears.[8]

And still, the reverses continued: Nashville and New Orleans fell and the new Federal commander, Major General George Brinton McClellan, moved his 121,000-man Army of the Potomac to Fort Monroe, Virginia, a monumental logistical feat. In the face of these developments and with the initial one year enlistments ready to expire, Davis took action: he asked Congress to suspend habeas corpus and declare martial law in the city and asked for the first conscription act in American history.

For most Richmonders, these were necessary measures, because 1862 saw a sudden spike in crime, vice and juvenile delinquency. Rival gangs of boys roamed the streets, the constant influx of soldiers and refugees led to the emergence of brothels, gambling dens and open drunkenness. Thus empowered, the Provost Marshal, John Winder, sent out his “plug uglies,” as locals called them to shut down houses of ill-repute, saloons and gambling haunts. [9]

Richmond also suffered from food shortages. Locals and the city’s newspapers decried “extortioners” who charged high prices for every day products. One resident wrote a relative, “It is a bad time for strangers to come to Richmond for we are really in such a state of I may say almost starvation, that it is utterly impossible to do more than get a scanty supply of provisions for the use of our immediate families.” War clerk J.B. Jones was appalled at the high cost of meat and butter. Most attributed the inflation to the large refugee population and the continued depreciation of Confederate money. [10]

Locals soon had other, more serious concerns. Beginning in early April, McClellan began his slow advance up the Peninsula between the York and James Rivers toward Richmond. Facing this formidable army was a 15,000-man force under the command of Major General John Bankhead Magruder. Magruder’s theatrics—he marched his men in circles, called out orders to non-existent units and mounted Quaker guns (logs painted to appear to be artillery pieces)—totally bamboozled the Federal commander, who assumed he was outnumbered two to one. As a result, McClellan moved cautiously and laid siege to Yorktown.

The overall Confederate commander, General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, was convinced he could not sustain his lines and defend against Federal gunboats and ordered a withdrawal to Williamsburg and after a fight there, on up toward the Confederate capital. Word of Johnston’s retreat toward Richmond set off alarm bells in the city and many locals, fearful the city would fall to the Federals as had New Orleans and Nashville, packed up their belongings and headed elsewhere. The President’s decision to evacuate his family did not bode well.

The city and state governments in Richmond acted quickly to allay the public’s fears. Both Mayor Joseph Carrington Mayo and Governor John Letcher promised to burn the city rather than let it fall into the enemy’s hands. Apparently, these promises soothed the locals’ fears and the exodus out of Richmond slowed considerably. Many wrote to relatives that although they could hear Federal cannon fire, they had confidence the Confederate army could push back the Federal juggernaut.

Johnston finally gave battle at Seven Pines on May 31, 1862. Davis, concerned about the action, rode out to the battlefield to observe. What he discovered was his commanding general seriously wounded. Davis had no choice but to turn to his military adviser, General Robert E. Lee, and placed him in command of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee lost no time in taking the initiative. From June 25 until July 1, Lee sought to isolate parts of McClellan’s army to defeat it in detail. Convinced he was outnumbered, McClellan demanded reinforcements from Washington and began to withdraw toward Harrison’s Landing. Despite only winning only one of the eight engagements in what is known as the Seven Days Battles, Lee had thoroughly out-generaled McClellan and saved Richmond.

Lee then decided to give the war torn Virginia countryside a rest while McClellan huddled at Harrison’s Landing. He sent Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson ahead to confront the newly created Army of Virginia under the command of Major General John Pope who had been successful in the west but had earned the ire of the eastern commanders with his brash ways. That braggadocio would be scotched as Lee and Jackson soundly defeated him at Second Manassas.

Although the Army of Northern Virginia was in bad shape—most of the men were shoeless and they were on short rations, Lee informed Davis the time was propitious to invade the north. For Lee, the situation in Virginia was desperate. Heavy fighting around Richmond and the environs had destroyed crops; fields lay fallow; in short, the country side could not support the army and the rapidly growing civilian population of Richmond. In the Antietam Campaign, Lee’s goals were to take the war out of Virginia, rally Maryland to the Confederate banner and seize the important railroad hub at Harrisburg.

The famous lost order 191 dashed those hopes. Two Union soldiers discovered cigars with a piece of paper wrapped around them in an abandoned Confederate camp site near Frederick, Maryland. Sensing the paper looked official, they passed it up the chain of command. McClellan, re-appointed head of the Union Army of the Potomac, famously declared, “’Here is the paper with which if I cannot whip ‘Bobbie Lee,’ I will be willing to go home.’” Basically, McClellan knew where every piece of Lee’s army was located and could have destroyed it. But he waited eighteen crucial hours to move and that allowed Lee to concentrate his army on Antietam Creek. [11]

The Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, was the bloodiest day of the war and at the end, both armies were located exactly where they were at dawn. Repeatedly, Lee’s army hovered on the brink of defeat, but McClellan’s habitual caution allowed Lee to move troops to threatened flanks. Boldly, Lee stood his ground on September 18, but then withdrew back into Virginia.

For Richmond, the battles of Second Manassas and Antietam added to the already overcrowded and strained hospital system. Thousands of wounded and captured men streamed into the Confederate capital. With winter approaching locals feared the outbreak of epidemic disease and possible starvation. Winter fuel was also a concern. The City Council continued its prodigious efforts to aid soldiers’ families, but with every Federal campaign launched against the South, be it in the eastern or western theaters, more refugees flocked to the beleaguered capital because they knew it would be defended to the last.

Despite Lincoln’s urging that McClellan move before the winter set in, he did not cross the Potomac until late October. Lee was able to counter the move and place Lieutenant General James Longstreet in front of McClellan while Jackson protected the ever important granary of the Shenandoah Valley. His patience exhausted, Lincoln replaced McClellan with Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside on November 7, 1862.

Burnside opted to attack Richmond from the north, but miscommunications and the failure to move his 110,000-man army on the railroads caused delays that allowed Lee to dig in on the high ground above Fredericksburg. On December 11, with the needed pontoon bridges finally on site, Federal engineers began to construct the bridges that would allow Burnside’s army to cross the Rappahannock. Confederate sharpshooters in Fredericksburg harassed the engineers but eventually, Federal units crossed the river and drove the Confederates from Fredericksburg. Along the way, they looted the town, after having shelled it.

The Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, was a major defeat for the Union army. Burnside suffered over 13,000 casualties from numerous frontal assaults against the firmly entrenched Confederates. Richmond was once again safe, but at a high cost: hundreds of homeless refugees streamed into Richmond along with the wounded from Lee’s army.

The dawn of a new year presented even more issues. As one local noted, “The scarcity of provisions was becoming a matter of serious consideration.” She went on to note that “A great portion of the territory, and especially the principal grain-growing section of Virginia, was in the occupation of the enemy.” In response, the Confederate Congress passed legislation calling for a tax-in-kind on agricultural goods and also an impressment law. The Congress also increased the amount of money in circulation which merely exacerbated an already high rate of inflation. Predictably, farmers withheld their goods from the market because government set prices were so low. Adding to the Richmond’s misery was the outbreak of small pox and scarlet fever. As Sallie Putnam noted, “there seemed to remain for us to endure only the last of the three great plagues—war, pestilence and famine!” [12]

The winter of 1863 was also quite severe, with over twenty measurable snowfalls. This compounded the food shortages. Once the snow melted, the dirt roads running into and through the city turned into quagmires of mud, which, in turn, kept away farmers who were willing to get their goods to market.

On March 13, 1863—Friday the 13th—Mary Ryan, a seasoned worker at the Brown’s Island munitions facility, had trouble with a friction primer. Frustrated, she banged the primer against a table. The primer exploded and the blast literally tossed her into the air. The explosion set off other shells and resulted in panicked girls and teenaged girls running outside to escape the flames. Some even jumped into the frigid waters of the James River. According to the Richmond Daily Dispatch, “Many of the poor creatures who were enabled to rescue themselves from the debris of the building ran about the island shrieking in their anguish, the clothes in flames, and themselves resembling avenging furies, while others who were too far disabled to move were stretched on litters. . .” What troubled most in Richmond was the reality the young girls were from working class families and thus, already heavily burdened by the high cost of food, fuel and lodging in the overcrowded city. The final casualty count was 33 dead, 30 wounded and one missing. [13]

In some respects, the Brown’s Island explosion was a metaphor for late winter and early spring in the Confederate capital: it was literally a powder keg atmosphere. This was the back drop to a meeting held April 1, 1863, at the Belvidere Baptist Church. The church was located on Oregon Hill, a working class neighborhood where many of the workers at the Tredegar Iron Works lived. The assembly was all women deeply concerned about the price of food. They resolved to meet at 9:00 a.m. on April 2 at the Governor’s Mansion to petition Governor Letcher for relief.

The women gathered as planned and were frustrated to discover the governor had already left for the capital. Irate, they began to move toward the commercial area of the city. War clerk J. B. Jones saw the growing crowd and asked one emaciated woman what the “celebration” was about. She replied, “We celebrate our right to live!” The women, armed and attracting others, began looting stores and carrying off food as well as shoes, clothing and luxury goods. Mayor Joseph Mayo and Governor Letcher were unable to quell the disturbance. A couple of eyewitnesses said President Davis appeared and threw coins to the crowd while threatening the public guard would fire on the mob if it did not disperse. [14]

Richmond was not the only Southern city wracked by a bread riot, but the Richmond riot was the largest and had the biggest impact. The Confederate government asked—begged might be a better word—the Richmond press not to print any accounts of it, fearful Northerners would use it for propaganda purposes. Most significantly, the Richmond City Council, with a long-standing commitment to poor relief, expanded the scope of its efforts, but with a notable shift: the Overseers of the Poor would distinguish between “worthy poor”—those who did not participate in the riot—and “unworthy poor,” those who did. Others in the capital were appalled by the violence and argued the “sufferers for food were not to be found in this mob of vicious men and lawless viragoes.” [15]

April also marked the beginning of the spring military campaign season. The new Federal commander, Major General Joseph Hooker, would embark upon yet another “On to Richmond” campaign. As had Burnside, Hooker concentrated on the Rappahannock-Rapidan line, but after moving aggressively, pulled back to the Wilderness around Chancellorsville. The resulting battle of Chancellorsville was Lee’s greatest victory, but at a high cost. After rolling up Hooker’s right flank, Stonewall Jackson, on a night reconnoiter, was accidentally shot by his own men. His left arm was amputated and he appeared to be recovering. Sadly for the Confederacy, he succumbed to pneumonia on May 10, 1863.

Jackson’s body was conveyed to the Richmond Capitol building, where he lay in state as thousands of mourners filed past. Richmond was draped in black crepe and the whole city was in full mourning. As one local noted, “A pall of deepest mourning mantled the South, and with impious hearts we inveighed against the will of God in the destruction of our idol.” After the funeral and procession, Jackson’s body was transported to Lexington, Virginia, for burial.[16]

The pall that fell over Richmond would not lift: in July of 1863 the Confederate capital received word of the twin Confederate debacles at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Confederate Ordnance chief Josiah Gorgas confided to his diary, “Yesterday we rode on the pinnacle of success—to-day absolute ruin seems to be our portion. The Confederacy totters to its destruction.” Another government official wrote, “This week just ended [July 10, 1863] has been one of unexampled disaster since the war began.”[17]

Military reverses were accompanied by ongoing concerns about starvation. Increasingly, members of the middle class found themselves doing without food so as to insure their children were cared for. War clerk Jones urged President Davis to sell civil servants “perishable tithes potatoes, meat, etc.) …at reasonable rates … when in excess demand of the army. I told him plainly, “Jones went on, “that without some speedy measure of relief there would be much discontent.” [18]

The approach of winter did little to allay Richmonders fears. Both the Richmond Whig and the Richmond Daily Dispatch predicted famine if impressment and price fixing were not modified. One local wrote in her diary, “I can’t think how people are to be fed and lodged.” Josiah Gorgas voiced similar concerns: “There is much anxiety on the subject of food for the capital.” As 1864 dawned, the situation mirrored that of the winter of 1863, except by 1864, the population of the Confederate capital had swelled to over 100,000 people; some estimated it was closer to 130,000. Many were forced to rely on friends and neighbors who lived outside of Richmond for food and other goods in order to make ends meet. [19]

To add to the misery, fuel was in short supply. In some cases, a mere stick of firewood commanded $5. The press and locals also noticed a disturbing increase in robberies, especially of foodstuffs.[20]

But the shortages and suffering were not universal. On February 12, 1864, the Richmond Enquirer published a blistering attack on the “reckless frivolity” that marked winter in the dilapidated city:

While General Lee’s army was on short rations, and often without meat—while the doors of Colonel Munford’s office were daily crowded with starving women, there have been those in Richmond who were spreading sumptuous suppers before their already well-fed neighbors and dancing with joy and delight, as though no want or famine were in the land; consuming the meat so much needed by the soldiers, and depriving the famishing poor of the little meat that came into the city… Is our National Independence to be disgraced by an imitation of the manners, customs and society of that fashion of strumpetcracy from which our people are struggling with such giant efforts to free ourselves? [21]

General Lee was also deeply dismayed at the prospect of rations for his army. In April he wrote to President Davis, “My anxiety on the subject of provisions for the army is so great that I cannot refrain from expressing it to Your Excellency. I cannot see how we can operate without present supplies. Any derangement in their arrival or disaster to the railroad would render it impossible for me to keep the army together, & might force a retreat into North Carolina. There is nothing to be had in this section for man or animals.” With only two days rations available he urged Davis, “Every exertion should be made to supply the depots at Richmond.” [22]

This was the situation when the spring campaigning season opened in May 1864. Lincoln had summoned the hero of Vicksburg, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant to take overall command of Federal forces. Grant moved east to oversee Major General George Gordon Meade and the Army of the Potomac. The ensuing Overland Campaign was a bloody slugfest that saw nearly continuous fighting from May 4 until the beginning of June. During that time, Lee lost his dashing cavalry commander, Major General J. E. B. Stuart while he tried to fend off Major General Philip Henry Sheridan’s Union cavalry advance on Richmond. He also admitted to Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, “We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there, it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” [23]

Lee was more prescient than he knew. On June 12-13, Grant directed the Army of the Potomac to pull out of its lines at Cold Harbor and move south. Grant’s plans went awry and allowed General P. G. T. Beauregard to block the Union army’s full advance. That allowed Lee to hasten his army to Petersburg and to entrench. Meanwhile, the Shenandoah Valley, a key source of Lee’s—and Richmond’s—supplies was being ravaged by Major General David Hunter. That campaign, coupled with Grant’s attacks on Lee’s rail lines, seriously compromised Confederate efforts to feed the army and the capital city.

On March 25, 1865, Lee attempted one last assault on Grant’s lines at Fort Stedman. It was repulsed. The next day, Grant ordered an all-out attack against all of Lee’s lines. On April 2, 1865, Lee sent word to Davis that the capital had to be evacuated; he could no longer defend Richmond. After four long years of war, the proud capital stood on the brink of self-inflicted destruction.

- [1] For the fullest analysis of Virginia’s road to secession see William A. Link, Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003) and Daniel Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989).

- [2] Henry Cleveland, Alexander H. Stephens, in Public and Private: with Letters and Speeches, before, during and since the War (Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1866), as quoted in Emory M. Thomas, The Confederate Nation, 1861-1865 (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1979), 13.

- [3] “Richmond 1861-1865,” in Official Publications of the Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee Issue 8: 6; Journal of the Acts and Proceedings of a General Convention of the State of Virginia Assembled at Richmond (Richmond, VA: Wyatt M. Elliott, Printer, 1861), 205.

- [4] Thomas Cooper DeLeon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals: An Inside View of Life in the Southern Confederacy (Mobile, AL: Gossip Printing, 1890), 99-100.

- [5] Richmond Daily Dispatch, May 30, 1861.

- [6] DeLeon, Four Years in Rebel Capitals, 86-87; idem, Belles Beaux and Brains of the ‘60s (New York: G. W. Dillingham, 1907); Katharine M. Jones, ed., Heroines of Dixie: Confederate Women Tell their Story of the War (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1955), 68.

- [7] Sallie Brock Putnam Richmond During the War: Four Years of Personal Observation, 1996 reprint ed. By University of Nebraska Press (New York: G. W. Carleton, 1867), 65-66.

- [8] Constance Cary, Recollections Grave and Gay (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911), 88-89.

- [9] Putnam, Richmond During the War, 113-14.

- [10] M. H. Ellis to Powhatan Ellis, April 14, 1862, Munford-Ellis Papers, Duke University; Diary entry for May 23, 1862 in J. B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, 2 vols. (Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 1866), 1:128.

- [11] John Gibbon, Personal Recollections of the Civil War (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928), 73, as cited in James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 537.

- [12] Putnam, Richmond During the War, 203; Ibid., 208.

- [13] Richmond Daily Dispatch, March 16, 1863,

- [14] J.B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, —1:285.

- [15] Putnam, Richmond During the War, 209.

- [16] Ibid., 219.

- [17] Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins, ed., The Journals of Josiah Gorgas, 1857-1878 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995), 74, 75; Edward Younger, ed. Inside the Confederate Government: The Diary of Robert Garlick Hill Kean (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), 79, July 10, 1863.

- [18] J.B. Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, —2:56, September 30, 1863.

- [19] Jones, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary, 2:68, October 11, 1863; Richmond Whig, October 30, 1863; Richmond Daily Dispatch, October 2, 1863, October 14, 1863; Emma Mordecai Diary, July 4, 1864, The Southern Historical Collection at the Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina; Wiggins, Journals of Josiah Gorgas, 98-99, April 11, 1864.

- [20] Putnam, Richmond During the War, 349-51.

- [21] Richmond Enquirer February 12, 1864.

- [22] Clifford Dowdey and Louis H. Manarin, eds. The Wartime Papers of R. E. Lee (Boston: Little Brown, 1961), 659, April 12, 1864.

- [23] Clifford Dowdey, Lee’s Last Campaign: The Story of Lee and his men against Grant, 1864, Bonanza Books ed., 1960 (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown, 1960), 355.

If you can read only one book:

Thomas, Emory M. The Confederate State of Richmond – A Biography of the Capital. Austen: University of Texas Press, 1971.

Books:

DeLeon, Thomas Cooper. Four Years in Rebel Capitals: An Inside View of Life in the Southern Confederacy. Mobile, AL: Gossip Printing, 1890.

Link, William A. Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Crofts, Daniel. Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Putnam, Sallie Brock. Richmond During the War: Four Years of Personal Observation, New York: G. W. Carleton, 1867.

Jones, J. B. A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, 2 vols. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 1866.

J. B. Jones, James I. Robertson Jr., ed. A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, 2 vols. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2015.

Organizations:

The American Civil War Museum

The American Civil War Museum comprises three sites: The Museum and White House of the Confederacy as well as Historic Tredegar, both in Richmond, and The Museum of the Confederacy-Appomattox in Appomattox, Virginia

1201 East Clay Street Richmond VA 23219

500 Tredegar Street Richmond VA 23219

159 Horseshoe Road Appomattox VA 24522.

Virginia Historical Society

The Virginia Historical Society collects, preserves and interprets the history of Virginia.

428 North Boulevard Richmond VA 23220

Web Resources:

The CivilWarTraveller provides useful information on Civil War events and locations in and around Richmond.

Civil War Richmond is an online research project to collect documents, photographs and maps pertaining to Richmond during the Civil War.

Civil War Photos has a page dedicated to Richmond.

The Encyclopedia Virginia entry on Richmond During the Civil War was authored by Mary DeCredico and Jaime Amanda Martinez.

Other Sources:

Richmond National Battlefield Park

The Richmond National Battlefield Park is operated by the National Park Service. The park offers an eighty mile driving tour covering 13 separate sites and four visitor centers. Contact the park service at 3215 East Broad Street Richmond VA 23223 804 226 1981