Stoneman's 1865 Raid

by Chris J. Hartley

Stoneman's raid across 6 Confederate states in March - May 1865

One of the longest cavalry raids in history – a raid that would cover as much as two thousand miles across six Confederate states – began on a note of frustration.

That particular emotion belonged to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. It was March 21, 1865, when he finally learned that the raid – Stoneman’s 1865 Raid – had begun. Grant had been pushing Major General George Stoneman to get started for two months. Bad weather and difficulties in gathering men, weapons, and horses had delayed it, forcing changes to the raid’s mission. Now, Stoneman was ordered to march his cavalrymen from Knoxville, Tennessee to southwestern Virginia, where they were to destroy railroad tracks and bridges and make noise as far as the outskirts of Lynchburg. From there the raiders would march into North Carolina to destroy rail lines around Greensboro and Charlotte. “Dismantling the country to obstruct Lee’s retreat,” Major General George Thomas called it. Still, Grant wondered if Stoneman’s raid would be too late to do any good.

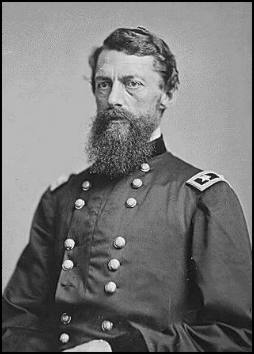

George Stoneman was eager to lead a successful raid. Born August 22, 1822, in Busti, New York, George Stoneman was an 1846 graduate of West Point. By this point in the war, Stoneman was best known for failure, starting with his much-criticized raid during the 1863 Chancellorsville Campaign. Then, the following year, while commanding the Cavalry Corps of the Army of Ohio, Stoneman had been ingloriously captured in Georgia while trying to free prisoners from Andersonville. Because of these mishaps, Stoneman had his share of detractors. After Stoneman was exchanged and released from a Confederate prison, Secretary of War Edwin Staunton and Grant ordered him relieved from duty. Major General John M. Schofield intervened and persuaded Stanton and Grant to revoke their order. Reenergized, Stoneman suggested a raid into Southwest Virginia. "I owe the Southern Confederacy a debt I am anxious to liquidate, and this appears a propitious occasion," he wrote. Stoneman executed the raid successfully in December 1864.

This foray may have vindicated Stoneman, but the New York general wanted to prove himself further. He got the chance when Thomas assigned him to command the District of East Tennessee in early 1865. Grant, Sherman, and Thomas subsequently drew up their proposed raid, and Stoneman went to work. Then came the endless delays. Another problem, at least as serious as the others if not more so, flared up too: hemorrhoids. The condition had plagued Stoneman for most of his military career, and 1865 was no exception.

Awaiting the raiders was a pitifully thin and scattered Confederate defense under General P.G.T. Beauregard. This would be one of the most difficult tasks the forty-six-year-old Creole had ever faced. “I could scarcely expect at this juncture,” he wrote, “to be furnished with a force at all commensurate with the exigency or able to make head against the enemy reported advancing from East Tennessee.” Nonetheless, Beauregard and other Confederate officials did their best. They gathered all the troops they could find and placed them at Salisbury, Greensboro, and Danville.

Map from: Chris J. Hartley, Stoneman’s Raid, 1865, Winston-Salem NC: John F. Blair, 2010.

On the morning of March 22, the skies finally cleared and Stoneman’s raid began in earnest. Over the next few days, the troopers moved quickly from Knoxville through east Tennessee. On March 28, the raiders entered North Carolina and attacked a home guard gathering At Boone. When the smoke cleared, the Federals had killed 9, captured sixty-eight, and burned the local jail.

Next, Stoneman decided to leave the mountains and move into the Yadkin River Valley to obtain supplies and fresh horses. He sent one column to Wilkesboro by way of Patterson's factory near Lenoir. Their march went smoothly. After sampling the corn and bacon stored at the factory, the column spent the night and then moved on to Wilkesboro. A rear guard stayed behind to destroy the factory and any remaining supplies. Meanwhile, Stoneman’s other column reached Wilkesboro late in the afternoon of March 29. Stoneman did not care to dawdle here, but rains made the Yadkin River unfordable. Three days passed before Stoneman was finally able to cross the Yadkin and get his men moving toward Virginia.

In Virginia, Stoneman encountered more resistance, but the raid continued unabated. At Hillsville, the Federal general divided his forces so he could destroy as much of the Virginia and Tennessee railroad as possible. One five hundred man detachment marched to Wytheville to raze the railroad bridges there, but ran into a stout Confederate force. The raiders managed to accomplish their mission but ultimately withdrew after suffering thirty-five casualties. Stoneman meanwhile took the rest of the division to Christiansburg, where they tore up railroad tracks in and around town. All told, the troopers destroyed over 150 miles of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. As a final gesture, Stoneman also sent a small detachment to create havoc as far as the outskirts of Lynchburg. After the war, veterans of this detachment would claim, with some hyperbole, that they played a role in the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at nearby Appomattox Court House.

Stoneman’s column returned to North Carolina on Palm Sunday, April 9, but only after one contingent encountered Confederate cavalrymen in the streets of Henry Court House (present-day Martinsville). Five Union troopers died and four others fell wounded before reinforcements tipped the fight in the Federals' favor.

The division reunited at Danbury, North Carolina. The next day the troopers marched on Germanton. Here Stoneman again divided the division. He sent one brigade, under Colonel William J. Palmer, “to destroy the bridges between Danville and Greensborough, and between Greensborough and the Yadkin River, and the large depots of supplies along the road,” while the rest of the command marched on Salisbury. Palmer’s men started their mission by capturing Salem on the evening of April 10. From there, Palmer moved on his next objective: the North Carolina Railroad, a key supply and reinforcement conduit for the Confederate forces facing William T. Sherman’s host near Raleigh.

Multiple detachments rode into the countryside. All were successful in destroying bridges, railroad track, depots, and manufacturing facilities near Greensboro and in Jamestown and High Point. “The same amount of damage, scattered over so large a territory, with so little loss was never accomplished by the same number of men during the Civil War,” a trooper boasted. One cavalryman, Lieutenant Colonel Charles F. Betts, would later receive the Medal of Honor for capturing a portion of a Confederate cavalry regiment near Greensboro. The only exception to this success was the contingent that rode for Abbott’s Creek, near Lexington. They ran into superior Confederate forces and were forced to withdraw. At dusk on April 11, Palmer’s Brigade – having reunited at Salem – marched to rejoin the rest of the division.

Meanwhile, Stoneman and two brigades marched southwest. He was bent on capturing Salisbury, which housed not only important railroad facilities and supplies but also a Confederate prison. Passing through Bethania, another Moravian community, the blue column aimed for Shallow Ford on the Yadkin River, where they arrived at 7:00 a.m. on April 11. A few home guardsmen were there, but the Federals dispatched them with ease. Moving on, the troopers arrived on the outskirts of Salisbury at daylight on April 12. There they found Confederate defenses awaiting them, drawn up along Grant’s Creek in a position of strength rarely encountered on this raid. Confederate artillery and small arms opened up. The Battle of Salisbury had begun.

On the morning of April 12, Salisbury was not well defended. Brigadier General William M. Gardner commanded Salisbury’s defenses, and he was assisted by Lieutenant Colonel John C. Pemberton. Pemberton had commanded Confederate forces at Vicksburg, which he surrendered on July 4, 1863. Now, Pemberton was a lowly lieutenant colonel of artillery on the run from fallen Richmond. Gardner and Pemberton had little to work with. Their motley army included government employees, home guards, regulars, prison guards, senior and junior reserves, citizen volunteers, and even some “galvanized” Yankees – foreign-born prisoners of war who had volunteered to serve in the Confederate army. At most, Gardner commanded five thousand men, but it was probably closer to half that number. Gardner and Pemberton divided this untried force, placing the larger detachment at the Yadkin railroad bridge north of town and a smaller force of about 1,000 men along Grant’s Creek. That stream was one of Gardner’s few advantages: it was deep, had steep banks, and protected the town’s northern and western perimeter. Another advantage was Confederate Major John W. Johnston’s veteran artillery battalion, which arrived in Salisbury late on April 11. Their dispositions were not ideal, however. The various batteries were not in supporting distance, and their flanks were vulnerable.

As these Confederates turned their weapons on the District of East Tennessee’s Cavalry Division, Stoneman decided that maneuver would win the day. He sent detachments to cross Grant’s Creek at multiple locations. Meanwhile, he ordered his artillery to unlimber in a position commanding the new Mocksville Road Bridge and open fire. Southern batteries barked in reply, outgunning the Federals. The blue battery lost as many as twenty men in the duel. Thus, the outcome of the battle was up to the horsemen, and everywhere they crossed Grant’s Creek they found success. In short order, Gardner’s right crumbled. The Confederate left did not give quite so easily. A Confederate battery there held the enemy at bay, but only for a while. Eventually Federal cavalrymen managed to outflank the artillery position. Then, once Stoneman’s cavalry had overcome both of Gardner’s flanks, they likewise overwhelmed the Confederate center. “The retreat soon became a rout…The pursuit was kept up as long as the enemy retained a semblance of organization and until those who escaped capture had scattered and concealed themselves in the woods,” a witness wrote.

By midday of April 12, after some additional skirmishing in town, Salisbury was firmly in Federal hands. Stoneman could now turn his attention to the wooden railroad bridge spanning the Yadkin River. Built in 1855, the bridge was an important link in the North Carolina Railroad. Confederate authorities built defenses on the north side of the river to guard it. About 1,200 soldiers manned the fort. Brigadier General Zebulon York, a veteran of the Army of Northern Virginia and a native of Avon, Maine, commanded the fort. The makeup of his command was similar to the force that had defended Grant’s Creek, but these men enjoyed the protection of the fort, with its well-placed cannon covering the approaches to the bridge and the obstacle posed by the river. As such, they were able to hold against the advance of one of Stoneman’s brigades. The Federals approached the bridge, opened fire on it half-heartedly, and later withdrew empty-handed.

To their lasting disappointment, the raiders also discovered that the hated Salisbury prison was empty, as its prisoners had been moved elsewhere. Fortunately, there was a consolation. Salisbury was simply jammed with Confederate supplies. One Federal was in awe when he described the “vast quantities of stores, ammunition, clothing, rations, coffee, sugar, meat, flour, corn, etc. etc.” that they seized. The raiders piled these goods in the streets of Salisbury and burned them. Stoneman’s troopers also destroyed the rails and railroad facilities in and around Salisbury. A reporter for the Carolina Watchman commented on the scene a year later. “The destruction of property was immense,” he wrote.

Stoneman did not mark time at Salisbury. On April 13, he divided his forces once again. One column rode west for Statesville, a depot of the Western North Carolina Railroad. Reaching the town with no trouble, the Federals occupied Statesville long enough to destroy some government stores, the railroad depot and the office of the Iredell Express newspaper. Meanwhile, the other column, under Palmer, went to Lincolnton to "watch the line of the Catawba" River and threaten Charlotte. Palmer’s men did just that. Contingents fanned out to capture and guard various fords and crossing points along the Catawba, including an important railroad bridge over the Catawba River in South Carolina. The brigade remained in the area until April 17, skirmishing with various Confederate cavalry detachments.

Meanwhile, to the west, the rest of the command passed through Taylorsville and reached Lenoir on Easter Sunday. One of Stoneman’s officers thought Lenoir a "rebellious little hole,” but Stoneman's presence prevented the troops from excessive mischief. There the troopers paused. Stoneman, who by now had heard rumors of Lee’s surrender, decided that he had completed his mission. On April 17, he left the division for East Tennessee, taking with him more than one thousand prisoners. Stoneman directed his second-in-command, Bvt. Brigadier General Alvan C. Gillem, to continue the raid toward Asheville.

Gillem marched only a short distance before he found Confederates guarding a bridge over the Catawba River just east of Morganton. Brigadier General John P. McCown, a West Pointer from Tennessee, directed the defense. At Murfreesboro, McCown had led a division of the Army of Tennessee; on this day, his command numbered only about eighty men, mostly home guards and local citizens. These Confederates managed to briefly hold the Federal forces at bay, until Gillem sent a flanking column to unhinge the enemy defense. Morganton fell in due course.

Confederate officials planned to defend Asheville too. Confederate Brigadier General James G. Martin, the commander of the District of Western North Carolina, posted five hundred men and four pieces of artillery in Swannanoa Gap on the road to Asheville. The blue-coated raiders reached Swannanoa Gap on April 20. Unable to push through the gap, Gillem sent a detachment through another gap, Howard’s Gap, several miles to the south.

With a Blue Ridge crossing now in Federal hands, Gillem continued marching on Asheville. He also summoned Palmer’s brigade, still at Lincolnton, to Rutherfordton in support. On Sunday afternoon, April 23, the Confederates again halted the Union advance, but this time it was with a flag of truce. Martin, having received official notification of Johnston’s and Lee’s surrenders, arranged to meet Gillem the next morning to discuss surrender terms. When they met, Martin agreed to cease resistance following the terms Sherman had granted to Johnston. Thus, on April 25, the Federals began withdrawing to their Tennessee base. However, when the Union government rejected the terms of the Johnston-Sherman agreement, Stoneman ordered his cavalry division to “do all in its power to bring Johns[t]on to better terms,” so it returned to Asheville and sacked it. The locals never forgot the result “Asheville will never again hear such sounds and witness such scenes -- pillage of every character, and destruction the most wanton,” recalled a citizen.

One last duty remained for Stoneman’s raiders. Jefferson Davis and the remains of the Confederate government were now in flight, and the cavalry division was in position to pursue. On April 23, Palmer – now in command of the division as Gillem had returned to Tennessee – learned of Lincoln's assassination and received orders to chase Jefferson Davis to "the ends of the earth." Accordingly, Palmer pushed his force into South Carolina and then Georgia. They narrowly missed capturing the fugitive president on several occasions, but as a consolation the division did capture Generals Braxton Bragg and Joseph Wheeler. Finally, on May 15, a unit from Major General James H. Wilson's command cornered Davis in Irwin, Georgia. But as General Thomas remarked to his staff, the Cavalry Division of the District of East Tennessee still could be proud. "General Wilson held the bag,” Thomas said, “and Palmer drove the game into it."

With that, Stoneman’s raid drew to a close. What did it achieve? Looking back, General Sherman thought that Stoneman’s last raid, together with a handful of other contemporaneous cavalry raids, dealt a fatal blow to the Confederacy. Grant was not so sure. “Indeed much valuable property was destroyed and many lives lost at a time when we would have liked to spare them,” he wrote in his memoirs. He had designed the raid to hasten the war’s end, but that did not happen. “The war was practically over before their victories were gained,” Grant went on. “They were so late in commencing operations, that they did not hold any troops away that otherwise would have been operating against the armies which were gradually forcing the Confederate armies to a surrender.” Yet the raid had telling effects that lingered. Instead of affecting the outcome of the war, Stoneman’s 1865 raid created conditions that retarded postwar recovery in the areas it struck.

If you can read only one book:

Chris J. Hartley, Stoneman’s Raid, 1865, Winston-Salem NC: John F. Blair, 2010.

Books:

Ina W. Van Noppen, Stoneman’s Last Raid, Raleigh NC: North Carolina State College Print Shop, 1961.

Ben F. Fordney, George Stoneman: A Biography of the Union General. United States: McFarland, 2008.

Joshua B. Blackwell, The 1865 Stoneman’s Raid Begins: Leave Nothing for the Rebellion to Stand Upon. United States: History Press, 2011.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Stoneman’s Raid, 1865. This website provides information on Chris Hartley’s book and related events.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.