Stuart's Chambersburg Raid

by Ted Alexander

Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid, October 9 – 12, 1862 was one of the final nails in the coffin for the military career of Major General George Brinton McClellan. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac was still a capable fighting force despite heavy casualties at Antietam. Conversely, Lee needed time to re–build his army. To secure this time he had to isolate the Federal army by cutting as many of its supply routes as possible. Lee issued orders to Major General J. E. B. Stuart to go into Maryland and Pennsylvania to disrupt the Cumberland Valley Railroad at Chambersburg and destroy the railroad bridge near there. Following the Battle of Antietam, that railroad had become an important supply line for McClellan’s army. With its terminus at nearby Hagerstown, Maryland, it was the nearest functional rail line to McClellan. Stuart’s 1,800 man raiding force passed through Maryland and entered Pennsylvania on the morning of October 9 and began taking prisoners and pillaging homes and businesses, sometimes “paying” with Confederate scrip, often just taking goods and horses. Entering Chambersburg that evening the raiders accepted the surrender of the town. For the next day the Confederates destroyed the railroad and affiliated buildings such as machine shops and the roundhouse. Warehouses were also torched after the Confederates took whatever they wanted from them. With Union forces closing in on them the Confederates took a roundabout route and after some clashes crossed the Potomac back to Virginia. Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid had been a morale booster for the South and a national disgrace for the Lincoln government. Stuart’s task force had traveled more than 130 miles in three days. During that time they had captured livestock and hostages and destroyed parts of the Cumberland Valley Railroad. However, the raid was something of a Pyrrhic victory for the Confederates. Much good horse flesh was worn out on the raid. Conversely, many of the horses that Stuart took from the Pennsylvania farms were large draft animals unsuited for cavalry use. The raid did constitute a blow to northern moral and was an embarrassment to the Union high command. It would be one of the final straws contributing to Lincoln’s dismissal of General George B. McClellan a few weeks later.

“... We have been most crazy on account of the rebel raid into Franklin Co. The idea of 2,500 cavalry passing through one end of our lines capturing horses and clothing, passing around the whole army and then unmolested going back into Virginia at the other end of our lines is the most ridiculous slur on our Generals and army ever heard of… It would be hard to describe the effect it has had on the 126. The Chambersburg boys were wild. They say they don’t blame the rebels but give them credit for the way the thing was accomplished and for the way they treated our people, but they curse our officers and the way the army is commanded.” [1]

This letter written by Private Samuel W. North, Company C, 126th Pennsylvania, from his camp near Sharpsburg, Maryland on October 14th, 1862, no doubt reflected the feelings of many soldiers in the Union Army regarding Confederate Major General J.E.B. Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid. His regiment was largely from Chambersburg and Franklin County, Pennsylvania. North was from the town of Mercersburg, one of the first places Stuart hit upon entering Pennsylvania. Indeed, Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid, October 9 – 12, 1862 was one of the final nails in the coffin for the military career of Major General George Brinton McClellan.

The bloody Battle of Antietam (or as the Confederates called it Sharpsburg), September 17, 1862, marked the end of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North. On the night of September 18, Lee withdrew his Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac back to Virginia.

Lee established his forces in the lower Shenandoah Valley along Opequon (pronounced O peck in) Creek, from Bunker Hill, Virginia (now West Virginia), eastward to Berryville, Virginia. During the move back into Virginia the Confederates destroyed several miles of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad between Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry., thereby rendering useless McClellan’s best means of transportation should he attempt to follow Lee into the Valley.

The sometimes overly cautious Union commander, fearing Lee still had a numerically strong army, decided to remain north of the Potomac River. Thus, the Confederates’ were free to rest, re–supply and increase their ranks in large part by the addition of stragglers who had fallen out at the beginning of the Maryland Campaign.

McClellan’s Army of the Potomac was still a capable fighting force despite heavy casualties at Antietam. Conversely, Lee needed time to re–build his army. To secure this time he had to isolate the Federal army by cutting as many of its supply routes as possible. He still did not know McClellan’s plans and if he were to regain mobility he needed horses.

Accordingly, after several days of consultation, Lee decided on a plan to fulfill his needs. Colonel John Daniel Imboden, was directed to move toward Cumberland, Maryland and attempt to disrupt the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. These were more than mere transportation arteries.

Perhaps the most important function of these two lines in the 1860s was as carriers of coal. By the mid-19th century coal was becoming important in the American economy both as a fuel and as a source of power. The Federal government itself increased its consumption from 200,000 tons in 1861 to more than a million by 1864. Despite Confederate threats approximately 318,000 tons were shipped east from the Cumberland region in 1862. Coal enhanced the importance of both the Baltimore and Ohio and Chesapeake and Ohio as targets. Imboden would disrupt these systems as much as possible. But Imboden’s movements would serve as a diversion for the main operation on Lee’s agenda.

On October 8, 1862, Lee issued orders to Major General J. E. B. Stuart to go into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Stuart was ordered to disrupt the Cumberland Valley Railroad at Chambersburg and destroy the railroad bridge near there. Following the Battle of Antietam, that railroad had become an important supply line for McClellan’s army. With its terminus at nearby Hagerstown, Maryland, it was the nearest functional rail line to McClellan and the Army of the Potomac, which was based in and around Sharpsburg, Maryland.

Lee also instructed, “Should you meet with citizens of Pennsylvania holding State or government offices… bring them with you, that they may be used as hostages, or the means of exchanges…” Hostage taking seems to have taken place in Virginia by Union authorities. Therefore, Lee saw this as a means for prisoner exchange and possibly as a form of retribution. [2]

Lee concluded his order to Stuart by stating, “should it be in your power to supply yourself with horses… you are authorized to do so…” Stuart would gather horses and other livestock on the raid. However, the benefit to his command was problematic. Most of his equine conquests in the “Keystone State” would be heavy farm animals unsuited for cavalry operations.[3]

The 1,800 man raiding column that Stuart led to Chambersburg was not bound by organizational unit integrity. Rather, this was a task force put together with troopers from an assortment of regiments. The major criteria was the quality of the mounts. Only those soldiers with strong healthy horses were selected for the raid. Also, many of the men had participated in Stuart’s first ride around McClellan that past June near Richmond, Virginia.

On October 9, the column was assembled at Darksville, Virginia. There Stuart’s force was organized in to three divisions of approximately 600 each. Brigadier General Wade Hampton III commanded the lead division into Pennsylvania. General Lee’s son, Colonel William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee commanded the next division, with the third being led by Colonel William Edmondson “Grumble” Jones. Major John Pelham commanded four guns of the Stuart Horse Artillery. Stuart also brought along two local guides. Captain Hugh Logan and his brother Alexander from the Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. area. This town located just north of the Mason Dixon Line was in Franklin County, in which Chambersburg was the county seat.

Around 3:00 a.m. on October 10, advance elements of Stuart’s column made their way across the Potomac River in the vicinity of McCoy’s Ferry Ford near Clear Spring, Maryland. After sparring with Union pickets, the Maryland shore was secured and the rest of the Confederate cavalry crossed the river.

Around 8:00 a.m., with Hampton in the lead, the Confederates next captured the Union signal station on nearby Fairview Mountain. Two Union officers managed to escape and spread the word of the Confederate presence to a Maryland Cavalry regiment that was in Clear Spring. While Stuart’s force traversed country roads and crossed the National Road on the trek to Pennsylvania they learned from some locals that they had just missed colliding with a large Union infantry force.

Incredibly, the “Kanawha Division” under Major General Jacob Dolson Cox had just passed by the head of the Confederate column in the thick morning fog, marching westward on the National Road. His command had been detached from service in West Virginia to serve with the Union forces around Washington about the time that Lee was threatening the capital in the Second Manassas Campaign. At Antietam Cox’s Division was attached to the IX Corps. Upon the death of Major General Jesse Lee Reno at the Battle of Fox’s Gap, September 14, 1862 Cox was given temporary command of that corps. Now just a few weeks after the battle of Antietam Cox was leading his command of around 3,000 men back to West Virginia. Elements of Stuart’s advance were able to capture 10 stragglers from Cox’s Division.

Stuart’s horsemen continued north on country back roads and across the line into Pennsylvania. Around 10:00 a.m. the column was halted and Stuart’s orders for the raid were read to the men. The general had issued strict orders for his men to exhibit magnanimity toward the citizens of Maryland, since many of them were pro–Confederate. Now that they were on Pennsylvania soil, the Rebels were free to “confiscate’ as many horses as possible. The local farmers were to receive “payment” in Confederate script or with receipts promising payment at a later date. Accounts vary as to the other livestock appropriated. Some accounts talk of cattle, hogs and sheep being herded along. Major Henry Brainerd McClellan, Stuart’s Chief of Staff, recalled that orders were issued just to confiscate horses, lest other types of livestock slow down Stuart’s column.

Although the men were instructed not to molest private property, there was a great deal of pillaging during the raid, mainly for food. Soldiers were seen riding along with meats such as roasted turkeys, and hams, while their saddles bags were stuffed with bread, butter and other delicacies.

The first hostage taken was Joseph Winger, a Federal official. Winger was the U.S. Postmaster at the village of Claylick located just a few miles south of Mercersburg. His son, Lieutenant. Benjamin F. Winger was an officer in the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery and happened to be in Chambersburg at the time on recruiting duty.

A total of nine citizens of Mercersburg were taken hostage. Among them were attorney and postmaster Perry Rice and G. G. Rupley, the town burgess or mayor. Postmaster Winger along with a hostage taken at nearby St. Thomas made for a total of 11 hostages. Two hostages were paroled at Chambersburg and two others escaped on the trek back to the Potomac. At least five others were taken back to Virginia and Richmond’s Libby Prison. All of these but Perry Rice were eventually released. Rice became sick while in Libby and died in January, 1863.

Practically all of the stores in Mercersburg were looted by the Confederates. One of the first places entered was the establishment of J. N. Brewer. Sources say that he lost from 400 – 600 pairs of boots and shoes. This was enough to equip nearly the entire 600 men of Stuart’s advance division, leaving the unfortunate store owner with only Confederate scrip to show for his “sales” that day

By around 2:30 p.m. on October 10, 1862, Stuart’s cavalry was headed out of Mercersburg on the way to Chambersburg. As the Confederates approached the village of St. Thomas, they sparred briefly with the local Home Guard. A few volleys were exchanged leaving one of the Home Guard dead and another, the town blacksmith, prisoner. This, the eleventh hostage, Thomas (Billy) Conner, would be interned at Libby Prison for six months.

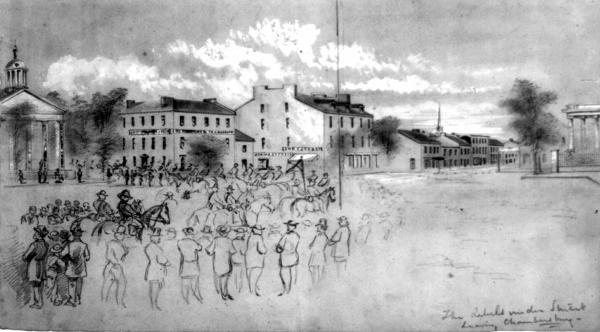

Meanwhile, evidence indicates that Stuart sent scouts into Chambersburg undercover in civilian garb. Riding through a heavy rainstorm, the head of Stuart’s column reached the outskirts of Chambersburg around 8:00 p.m. Soon a squad of the grey clad cavalry was sent into the town with bugles blaring. This advance unit met with a delegation of prominent local citizens which included Alexander K. McClure.

McClure was a fervent abolitionist and Republican. He was also the editor of the Franklin Repository newspaper. In the 1850s he served several terms in the Pennsylvania state house. At the 1860 Republican National Convention he played a major role in swinging Pennsylvania’s votes to Abraham Lincoln. Later he helped get Andrew Gregg Curtin elected governor of the state. In September 1862 he was appointed as an assistant adjutant general by Lincoln.

McClure and several other prominent townsmen negotiated the unconditional surrender of Chambersburg with Stuart and Brigadier General Wade Hampton, who had been designated ‘Military Governor” of the town. The terms of the surrender agreement stated that no private property was to be molested. Government officials were still fair game to be taken hostage and McClure was one of them. He would return to Norland, his estate north of town, to await his fate.

As the Rebels went about their work cutting the telegraph and cleaning out bakeries and warehouses where flour was stored, the Chambersburg telegrapher was able to send a message to Governor Curtin in Harrisburg, who in turn notified the War Department in Washington. A visit to the local bank yielded an empty vault since all money had been sent to Philadelphia upon hearing of Lee’s invasion. That evening Stuart and his staff made their headquarters at the Franklin House Hotel, located on the southwest corner of the “Diamond”, or town square.

Around 9:00 p.m., elements of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry, were ordered to ride north to the village of Scotland. There they were to burn the important Cumberland Valley Railroad Bridge across Conococheague Creek. Since the railroad had become a major logistics link for McClellan following the Battle of Antietam, its destruction would be a serious blow to Union resupply efforts.

En route on this mission the Confederates ran into several locals who told them that the bridge was made of iron and could not be burned. Taking these claims at face value and wanting to get in from the pouring rain that night, the Rebels turned back toward Chambersburg. The bluff had worked. It was actually a wooden bridge. The following June it was burned by Confederate cavalry during the Gettysburg Campaign.

Around 1:00 a.m. on the return to Chambersburg, the bridge burning expedition stopped and bivouacked at Norland, the country estate of A. K. McClure. There they fed their horses in McClure’s 60 acre cornfield. McClure invited more than a hundred officers and men into his house where they were treated to coffee, tea, bread and fine tobacco for the rest of the night. Around 4:00 a.m. the Confederates mounted up and left to join the main command. It is believed that out of respect for his hospitality, McClure was not taken prisoner by them.

Stuart and his command mounted up to leave Chambersburg on the morning of October 11, leaving several detachments behind to wrought destruction on the railroad and affiliated buildings. This included the Cumberland Valley Railroad Depot House, machine shops and roundhouse. The adjacent warehouse of government contractor Wunderlich and Nead was also torched. It contained uniforms, hats, and other equipment as well as weapons. What was not salvaged by the Rebels was burned. One account stated that 700 muskets, 400 pistols and 468 boxes of ammunition was among the booty. Several hundred blue Union uniforms were also taken.

Ammunition in the warehouse and in box cars on the rail siding was blown up. This was from Longstreet’s ammunition wagon train that had been captured near Williamsport, Maryland on September 15 by Union cavalry that had escaped from Harpers Ferry prior to its surrender to Stonewall Jackson.

Ironically, these same warehouses were used in the summer of 1859 by John Brown. At that time, weapons in boxes stamped “farm implements” were brought there for storage as Brown and his men planned the Harpers Ferry Raid.

The troops involved in destroying the rail yards and warehouses did not leave Chambersburg until around 9:00 a.m. on October 11. Stuart with his main column was already moving east toward Cashtown. Here the Confederates rested, fed their mounts and sent out foraging parties to gather more horses. Near Gettysburg one of the foraging details skirmished with a detachment of Union scouts and one Confederate cavalryman was captured. While this was done the gray clad cavalry stopped at the Cashtown Hotel, helping themselves to 200 gallons of whiskey along with smaller quantities of wine and other commodities. The raiders then moved southward to Fairfield. There stores were looted and around $1,000.00 worth of merchandise taken.

By now a dragnet of Union forces was tightening around Stuart as he led his column, which at times stretched for five miles, south through Frederick County, Maryland. Both Yankee cavalry and infantry were moving out of towns such as Hagerstown and Frederick to intercept the gray column. As Stuart pressed on toward the Potomac he learned that a Union cavalry force of about 800 strong under Brigadier General Alfred Pleasanton was in the vicinity of Frederick, Maryland, just a few miles to his front.

In order to avoid the Yankee cavalry, Stuart moved his column on a circuitous route to the east. At New Market, Maryland Stuart, and some of his officers took a detour to Urbana, Maryland. There on September 8, 1862, he had stopped with his staff at a girl’s school for what became known as the “Saber and Roses Ball.” Remembering the good time had there and his promise to return to visit a New York women dubbed the “The New York Rebel”, Stuart, ever the gallant cavalier, was now returning to keep that promise. After a brief respite with the ladies, and with several thousand Union troops closing in, Stuart mounted up and rejoined his command.

By the morning of October 12, 1862, Stuart was near the town of Barnsville, Maryland about two miles from the Potomac. Blocking his path were around 2,300 Union artillery, cavalry and infantry under Brigadier General George Stoneman, Stuart had hoped to cross the Potomac near the mouth of the Monocacy River. Finding that point and others heavily guarded by Union infantry and cavalry, he was led on a shortcut to White’s Ford. His scout for this leg of the raid was Captain Benjamin Stephen White, a native of the area.

The advance of Stuart’s command soon clashed with the 8th Illinois Cavalry. The fact that many of the Confederates were wearing Union greatcoats confiscated at Chambersburg caused hesitation in the Union ranks and the Union cavalrymen were forced to retreat in the face of a Rebel charge. Soon both sides were supported by artillery. When the 3rd Maine Infantry attempted an attack on the Confederate cavalry they were confounded by the friendly fire of the Union guns mistakenly directed in their midst.

The well-directed fire of Major John Pelham’s Confederate artillery caused Pleasanton to think that Stuart’s force was stronger than what it actually was. Although the Union commander had around 400 cavalry, elements of the 4th Maine infantry and several guns, he paused for almost two hours to wait for reinforcements.

As Stuart’s column sparred with Pleasanton, a second Confederate column under Colonel William “Rooney” Lee and Colonel William “Grumble” Jones took a short cut toward the river. As the Confederates approached the towpath of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, they discovered that it was held by around two hundred infantry of the 99th Pennsylvania under Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Ruthwin Biles.

Lee sent a message to Stuart for help but was told that he was on his own. Accordingly, young Rooney decided to bluff the Yankees by sending a trooper forward under a flag of truce to inform the Union infantry commander that they were outnumbered and had 15 minutes to surrender. Otherwise, the blue-clad infantry would face a bloody encounter. The arrival of Hampton’s cavalry and several well place artillery rounds from the Rebel guns became the deciding factor. Biles, whose command was composed of green troops ordered a swift withdrawal from the area.

With the absence of the Union infantry, the way was now unimpeded to cross the Potomac back to Virginia. Soon Stuart’s entire force was making its way across the river with one of Pelham’s guns keeping Pleasanton’s troops at bay long enough for a successful crossing.

Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid had been a morale booster for the South and a national disgrace for the Lincoln government. Stuart’s task force had traveled more than 130 miles in three days. During that time, they had captured livestock and hostages and destroyed parts of the Cumberland Valley Railroad. However, the raid was something of a Pyrrhic victory for the Confederates. Much good horse flesh was worn out on the raid. Conversely, many of the horses that Stuart took from the Pennsylvania farms were large draft animals unsuited for cavalry use. The raid did constitute a blow to northern moral and was an embarrassment to the Union high command. It would be one of the final straws contributing to Lincoln’s dismissal of General George B. McClellan a few weeks later.

- [1] Ted Alexander, The 126th Pennsylvania (Shippensburg, PA: Beidel Publishing House, 1984), 117-8.

- [2] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 19, part 2, p. 55.

- [3] Ibid.

If you can read only one book:

Thompson, John W. Horses, Hostage, and Apple Cider: J.E.B. Stuart’s 1862 Pennsylvania Raid. Mercersburg, PA: printed by author, 2002.

Books:

Alexander, Ted, ed. The 126th Pennsylvania. The 126th Pennsylvania. Shippensburg, PA: Beidel Printing House, 1984, 117-8.

Conrad, W. P. and Ted Alexander. When War Passed This Way. Greencastle, PA: Greencastle Bicentennial Publication/Lilian S. Besore Memorial Library, 2002, 89-92.

Hoke, Jacob. Historical Reminiscences Of The War; or, Incidents Which Transpired in and About Chambersburg During the War of the Rebellion. Chambersburg, PA: M.A. Foltz, 1884, 28-33.

McClellan, H. B. The Campaigns Of Stuart’s Cavalry. Fredericksburg, VA: Blue and Gray Press, 1993, 136-66.

Price, Channing. “Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid: An Eyewitness Acount,” in Civil War Times Illustrated 4, no. 9 (January 1966): 8-15, 42-44.

Trout, Robert J. With Pen And Saber: The Letters And Diaries Of J.E.B. Stuart’s Staff Officers. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 1995, 104-13.

United States War Department. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 19, part 2, p. 52-4.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This page from ExplorePAhistory.com locates the marker in Pennsylvania commemorating raid and contains a brief discussion, map and Civil War era drawings relating to the raid.

The Harpers Weekly article on November 1, 1862 describing Stuart’s Chambersburg Raid is available online here.

This brief article in the Valley of the Shadow Archives at the University of Virginia, has a transcription of a local news story, correspondence, a diary and a map of the all relating to the raid

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.