Tariffs and the American Civil War

by Phillip W. Magness

Tariffs are a tax levied on imported goods and were the dominant source of the federal government’s revenue in the 19th century. Tariffs were also used for protectionist purposes, benefiting largely northern manufacturing businesses and effectively raising the costs to southern agricultural exporting industries. Tariffs also spawned corruption and political favoritism for some industries over others. Tariffs played an important role in the early development of secessionist constitutional theory. But as an object of antebellum national political discussion, tariffs occupied a distant secondary place behind slavery. Yet tariff arguments continuously attracted the attention of Congress from its first meeting in 1789 until the Secession Winter session of 1860-61. The last great antebellum tariff battle, the Morrill Tariff of 1861, was adopted only two days before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, and largely defined the dimensions of American international trade policy for the next fifty years. Following the War of 1812, Henry Clay developed the idea of the American System consisting of an integrated economy where tariffs excluded European producers, and federal investments in a vast network of internal improvements—roads, canals, harbor facilities, and eventually railroads—would supplant the trans-Atlantic trade with a new pattern premised on internal economic autonomy. High tariffs under the American System were implemented in 1824, and raised even further in the 1828 ‘Tariff of Abominations,’ as it was described by Southern free-trade advocates. In 1833 the Compromise Tariff was introduced gradually reducing tariffs over a nine-year period. Congress swung back from a relatively free trade position with a partial restoration of tariffs with the 1842 Black Tariff. President James Polk began reforming tariffs in 1846 with moderate rate reductions. These reforms also standardized assessments onto a fixed ad valorem schedule in which tariffs were assessed as a percentage of the import’s declared value, replacing the old discriminatory system of specific duties on specific goods. In 1857 there was a further uniform reduction in tariff rates. Then the Panic of 1857 saw yet another reversal of course when federal revenues declined significantly. Work began on the Morrill Tariff in 1859. In the 36th Congress no party held a majority and tariff supporting Republicans faced off against anti-tariff Democrats in a 44 ballot stalemate over the selection of the new speaker of the House of Representatives. In early 1860 the Morrill tariff passed in the House not only raising tariff rates but replacing Polk’s ad valorem system with the reintroduction of a specific duties-based system. The vote was almost strictly on north-south sectional lines in the House but the Senate tabled the measure where it languished until early December 1860 when it was reintroduced. With southern delegations of seceding states no longer in Congress to block the measure, the Morrill Tariff was signed into law by President James Buchanan in March 1861. British opinion at the time favored free trade and the Morrill Tariff was detested in Britain. This development lent unexpected sympathy to Confederate efforts to secure British support early in the war, but was eventually eclipsed by the Emancipation Proclamation after which British public opinion swung behind the Union. For the northern government’s diplomacy, the Morrill Tariff had been a shortsighted strategic blunder. It unintentionally alienated an otherwise natural anti-slavery ally for what could, at best, be described as short term economic favors to a few politically connected firms and industrialists. The Confederacy eagerly exploited this misstep in its unsuccessful quest for diplomatic recognition, yet in doing so also elevated the tariff cause from its role as an ancillary complaint to a centerpiece of Lost Cause historiography. What started as a lesser secessionist grievance, only to be adapted into a somewhat diversionary diplomatic tactic with Britain, returned as a rationalized “memory” in the postbellum sorting of the war’s physical destruction and slavery’s moral baggage. Whereas antebellum tariff battles saw the country pivot between competing regimes of protection and relatively free trade, the Civil War inaugurated a semi-permanent political ascendance of the tariff’s industrial beneficiaries in the Gilded Age. Traditional free trade constituencies in the absent and then politically weakened south, along with the agricultural west, were unable to regain the upper hand until the Woodrow Wilson administration. As a result of its settlement in 1861 and its wartime entrenchment, the tariff remained the dominant topic of American economic policy until the eve of the First World War.

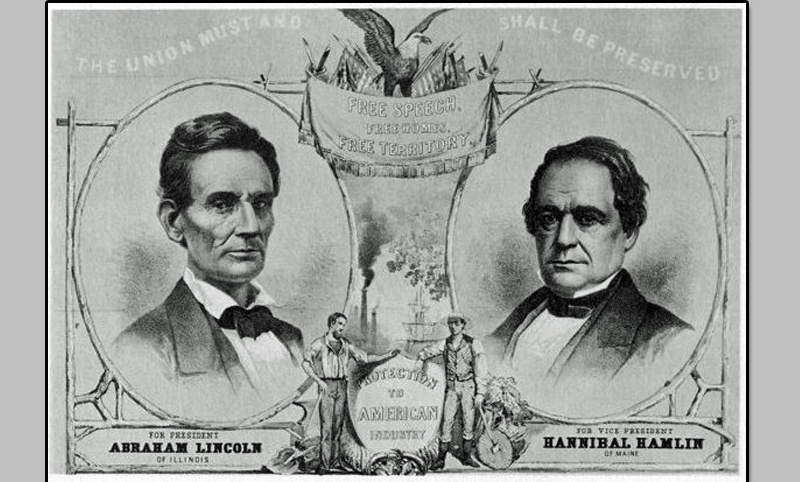

Lincoln Hamlin 1860 Election Poster

Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-07990.

Heated debates over the tariff schedule heavily influenced American economic policy before the Civil War. As an object of national political discussion, they occupied a distant secondary place behind slavery. Yet tariff arguments continuously attracted the attention of Congress from its first meeting in 1789 until the Secession Winter session of 1860-61. The last great antebellum tariff battle, the Morrill Tariff of 1861, concluded only two days before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, and largely defined the dimensions of American international trade policy for the next fifty years. The recurring prominence of the issue is directly evidenced by its central importance to the federal government’s revenue system. On the eve of the war in 1860, tariffs brought in $53,188,000, or almost 95% of the federal government’s tax receipts.[1] No other revenue source would approach the tariff’s preeminence until the adoption of the income tax in 1913.

Contrary to a popular strain of postwar mythology, tariffs did not “cause” the Civil War. Tariffs did however play an important role to the early development of secessionist constitutional theory. Of equal significance, the reemergence of the tariff issue after the Panic of 1857 added additional stresses to the existing national fissure over slavery. A hasty settlement of Morrill Tariff of 1861 at the peak of the secession crisis somewhat carelessly weakened the Union’s geopolitical position in Europe at the outset of the war. It also provided an unintended boost for the Confederacy’s early attempts to coax diplomatic recognition and support from Great Britain, and shaped the direction of American tariff policy for the next half century.

The Political Economy of Tariffs

The concept of a tariff, or a tax that is levied upon imported goods, is relatively simple to understand. Tariffs were one of the main revenue-generating powers given to Congress at the constitutional convention. They also provided the core of the first national tax system, and quickly became the dominant source of the federal government’s revenue in the 19th century.

Tariffs introduce complex political economy questions however, as tax revenue is not always their only objective. Since tariffs target imported products from abroad, they may also be enlisted as a powerful tool to benefit the domestic industries of a country. Known as the theory of protectionism, this strategy involves the levying of a high duty upon a specific import, or broader category of imported goods, with the express intention of raising its price on the home market. The higher price on imports, in turn, is said to benefit American producers of the same good over their foreign competitors, encouraging economic development at home.

The protectionist strategy is somewhat counterintuitive from a taxation perspective, as a completely “protected” good would technically be taxed at such a high rate that it is excluded from importation and accordingly generates no revenue. This characteristic actually places revenue tariffs and protection in tension with each other. If the tariff schedule’s rates are raised too high, it will succeed in keeping foreign products off of the domestic market but at the expense of the ability to generate revenue for the government. This tradeoff between revenue tariffs and protective tariffs, as well as the competing interest groups behind each position, provided a constant source of tension in antebellum economic policy.[2]

The Tariff Before the Civil War

While revenue tariffs trace to the earliest tax debates of the First Congress in 1789, protectionist tariffs received a powerful advocate in the first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. In 1791 Hamilton published his famous Report on Manufactures, which laid out a strategy of using tariffs and other trade regulation mechanisms to promote America’s “infant industries” against their European competitors.[3] Most economists today question the soundness of Hamilton’s theory due to the economic inefficiencies and distortions that are created by high tariff regimes. His report nonetheless proved highly influential in the early republic and continued to influence American trade policy until the early 20th century.

Following the War of 1812 and the resumption of international commerce with Great Britain, tariffs again became an object of national political contention. Modest protectionism initially received support from nationalist politicians among Congress’ War Hawk faction, resulting in the Tariff of 1816. This postwar consensus did not last long, devolving into two competing economic visions for the country over the next four years. On the protectionist side, Henry Clay of Kentucky adapted Hamilton’s arguments to a larger economic platform that he titled the American System. His proposal utilized high protective tariffs on manufactured goods to encourage the development of American industry in the absence of foreign competition. As the American System evolved, Clay drew on the work of Hamiltonian economists such as Friedrich List, a German visitor to the United States in the 1820s, as well as Pennsylvania’s Mathew Carey to devise a conscious strategy of import substitution. According to this belief, the economy of the United States could be “harmonized” into self-sufficiency if raw materials, including southern cash crops such as cotton, were redirected from the established factories of Great Britain to the nascent textile mills of New England. They could then be processed into finished goods and sold to American consumers. Clay envisioned an integrated economy where tariffs excluded European producers, and federal investments in a vast network of internal improvements—roads, canals, harbor facilities, and eventually railroads—would supplant the trans-Atlantic trade with a new pattern premised on internal economic autonomy.

Clay’s tariff-based American System was not without its complications, political and otherwise. As his promised economic “harmonization” depended heavily upon shifting the sale of southern agricultural products from Europe to northern factories, it carried the potential of becoming an economic boon to the slave plantation system. This realization was anathema to antislavery northerners such as Carey, and even slaveholding moderates such as Clay himself, who otherwise hoped that economic development would in time render slave labor inefficient and phase it from the American political landscape. As a result, many American System proponents turned to gradual compensated emancipation and the subsidized colonization of the ex-slaves abroad as tools intended to wean the country of slavery in conjunction with the tariff system’s adoption.[4]

The tariff simultaneously evoked intense political opposition, particularly amongst the Jeffersonian-Republicans and their Democratic Party successors, on account of its tendency to attract political favoritism and corruption. Early tariff politics proved highly susceptible to political lobbying by beneficiary industries. Iron producers in Pennsylvania, wool interests in Vermont, and factory owners along the eastern seaboard used the cover of protection to secure privileged and favorable tariff rates for their own raw materials, or to discriminate against competitors at home and abroad through the tax’s imposition of higher prices.

Protective tariffs also tended to disproportionately penalize some sectors of the domestic economy while benefitting others, prompting charge that they created an unequally administered and even regressive tax system. Merchants who were involved in the existing trade with Europe saw the potential loss of their livelihood, both in the induced decline of shipped goods and the risk that foreign powers would retaliate against American exports with protective tariffs of their own. The agriculture-heavy export industry faced similar threats from abroad as well as the burdens of what economists now call the symmetry effects of the tariff—since exporters must sell their goods at an international market price, they lose the ability to pass through some of the costs of the tariff to their buyers even as they must absorb higher domestic prices for their own consumption.[5] This latter effect also complicated the tariff’s relationship to slavery. Even as Clay intended for southern crops to supply the textile mills of New England, the cotton industry boom of the early 19th century sent most of its product to the established mills of Great Britain.

The tariff’s burdens on the export market, combined with its reputation for favoritism, spawned a succession of heated political debates following a failed attempt by the American System’s backers to increase the tariff schedule in 1820. The emerging split had sectional dimensions, pitting the industrializing northeastern manufacturers against a coalition of southern cotton producers, western state farmers, and New England merchants engaged in the export trade. Though economic interests motivated each, much of the controversy focused upon the tariff schedule’s susceptibility to political favoritism and lobbying. As John Taylor of Caroline, a member of the Jeffersonian old guard and Senator from Virginia charged in 1822, what use was the Constitution’s prohibition of taxes on exports “if Congress can impair or destroy this right of exportation for the sake of enriching a local class of capitalists” with a tariff? [6]

After an initial defeat in 1820, the Clay-backed protectionist faction won a series of key congressional votes, raising rates to protective levels in 1824 and again in 1828, with the latter being dubbed the Tariff of Abominations by the increasingly southern advocates of the free trade position. The 1828 Tariff increased the average rate to a historical peak of over 60% - in part, a product of miscalculations by southerners who sought to defeat the bill by loading down in exorbitant rates. The tariff cleared Congress to their chagrin and gained the signature of President John Quincy Adams. The resulting measure proved immensely controversial on sectional lines, and sparked the largest constitutional crisis of the early republic until the Civil War. Instigated by Vice President John C. Calhoun and following a modest revision in 1832 that the southerners deemed insufficient to meet their demands for tariff relief, the state of South Carolina adopted an ordinance of nullification to void the objectionable tariff schedules within her boundaries. After an exchange of pamphlets and declarations that nearly brought the state into a physical confrontation with the administration of Andrew Jackson, Congress adopted a Compromise Tariff in early 1833 that gradually reduced the objectionable rates over a 9-year calendar, to be implemented in stages.

The Nullification Crisis directly presaged the Civil War itself on at least two fronts. First, while the political battle took place over the question of protection versus free trade, the tariff question functioned as a proxy issue for the emerging sectionalization of American politics over slavery. As Calhoun wrote in an 1830 letter:

I consider the tariff act as the occasion, rather than the real cause of the present unhappy state of things. The truth can no longer be disguised, that thepeculiar domestick institution of the Southern States and the consequent direction which that and her soil have given to her industry, has placed them in regard to taxation and appropriations in opposite relation to the majority of the Union. [7]

After nullification, sectional politics became an increasingly pronounced feature of congressional debates, particularly those concerning slavery. The crisis also illustrated the south’s status as a minority faction in Congress, particularly after Congress adopted a Jackson-backed Force Bill that strengthened the powers of federal customs collectors and the federal judiciary to prosecute customs evasion by the state.

The second significant development from the Nullification Crisis was its role in formalizing the compact theory of the Constitution, and with it the doctrine of secession. The tariff provided an occasion to test the constitutional arguments of Calhoun and the nullifiers, as they applied to a theorized states’ rights check upon the powers of the federal government with increasing relevance to slavery. Calhoun contended that the Constitution’s tariff power was effectively chained to its revenue function, meaning it envisioned taxation on imports that would be physically collected and entered into the treasury. Since tariffs on the protective end of the scale intentionally exclude goods from being imported, they actually diminish tax revenues. Explicitly protective tariffs therefore lacked sanction under the revenue clause of the Constitution, or so the argument went. [8] This in turn provided a pretext for the states to “nullify” what they deemed to be an unconstitutional law. The tariff issue accordingly became the first national test case for legal theories that were later enlisted by the secessionists to form the breakaway Confederate States of America.

The 1833 compromise largely defused the tariff issue for the moment and induced a retreat from the constitutional brinksmanship of the South Carolinians, although Congress would again swing from a relatively free trade schedule to reinvigorated protectionism in 1842, the so-called Black Tariff in reference to its partial restoration of the Tariff of Abominations of 14 years prior. The fallout from this upward tariff revision became an electoral liability in the 1844 presidential election. Democrat James Knox Polk routed Whig Henry Clay, in part due to an outmaneuvering on the tariff issue. Whereas Clay had long been regarded as the protectionist standard bearer of national politics, Polk carved out a cautiously worded free trade position in a publicly released campaign statement that has since become known as the Kane Letter. This document endorsed a downward revision of the schedule toward a “tariff for revenue,” though one with “moderate discriminating duties” that provided “incidental” protection as a secondary object to its tax function. Polk’s careful parsing of the tariff’s “revenue” and “incidental” effects passed the claimed constitutional muster of the old nullification debate. [9] As president he delivered on his promise in 1846 when, under the guidance of Treasury Secretary Robert J. Walker, Congress adopted a comprehensive overhaul of the tariff system featuring a moderate downward revision of rates and, importantly, the standardization of tariff categories on a tiered ad valorem schedule.

This final feature was intended to improve the transparency of the tariff system by consolidating the somewhat convoluted list of tariff items, itself the product of many decades of lobbying and the carving out of highly specialized categories as political favors for specific companies and industries. By converting the tariff from a system that relied primarily on itemized specific duties or individually assigned ad valorem rates to a formal tiered schedule of ad valorem categories in which tariffs were assessed as a percentage of the import’s declared dollar value, Walker further limited the ability of special interests of all stripes to disguise tariff favoritism in units of volume and measurement—different tariff rates assessed by tons of iron, gallons of alcohol, yards of cord and so forth.

The Walker reforms helped to stabilize many years of fluctuating tariff politics by instituting a moderately free trade Tariff-for-revenue system that lasted, subject to a further uniform reduction of rates in 1857, until the eve of the Civil War. It also carried important geopolitical connotations, as Walker strategically designed and implemented the tariff to coincide with Great Britain’s repeal of its own protectionist Corn Laws the same year. These concurrent measures effectively initiated a pattern of joint trade liberalization between the two countries. [10] Specific beneficiaries included the United States’ agriculture-heavy export sector, which included western-produced grains and wheats as well as southern-produced cotton. The booming trade of King Cotton that followed in the early 1850s would have significant implications for the perception of secessionism abroad, as well as the Union and Confederacy’s contest to prevent or draw the European powers into the Civil War.

The Morrill Tariff and a Reversal of Course

In late August 1857 the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company suspended operations due to looming financial insolvency, an event that is generally considered the starting point of the Panic of 1857. Economists today trace this economic downturn’s causes to a complex mixture of international price shocks, speculative land bubbles on the western frontier, and the discovery of corruption in the railroad bond market. To many observers in 1857 though, the tariff schedule was the culprit behind this growing economic recession. Philadelphia economist Henry Charles Carey, the son and protectionist heir of Mathew Carey, placed the blame squarely upon a further reduction of the Walker Tariff rates that had been adopted the previous March. The younger Carey formalized this argument in his 1859 book, Principles of Social Science, which advocated the adoption of a proactive and increasingly protectionist tariff schedule as a means of bringing about economic relief from the lingering recession. [11]

Facing growing public debt caused by a decline in tax revenues amidst the Panic, President James Buchanan used his annual message to Congress on December 6, 1858 to request a revision of the tariff schedule. An ambiguity of intentions surrounded Buchanan’s message from the outset. As a Democrat, he represented the party most philosophically aligned with the moderately free trade revenue tariff system that had been in place since the Polk administration. Yet Buchanan also hailed from Pennsylvania, home of an aggressively protectionist iron industry and a political hotbed of Carey’s economic doctrines.

Work on a tariff revision began in the lame duck session of Congress in early 1859. House Ways and Means Committee chairman John S. Phelps, a Democrat from Missouri, began preparing a modest tariff increase to purportedly “stimulate revenue” in line with a common interpretation of Buchanan’s position. Republican committee member Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont proposed a more aggressive protectionist revision. Meanwhile free traders led by Senate Finance Committee Chairman Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, a Democrat from Virginia, espoused staying the course under the March 1857 revised schedule. When the session expired in March 1858, an impasse had emerged around the tariff issue. The resulting division spilled over into the incoming 36th Congress, where no party possessed a clear majority in the House of Representatives.

Though slavery was at the forefront of the contest, the tariff issue played a determinative role in the 44-ballot stalemate over the selection of a new Speaker of the House when Congress reconvened in December 1859. The Republican plurality initially favored Ohio Representative John Sherman, a protectionist aligned with Morrill. Amidst the extended two-month balloting period, free trade Democrats twice rebuffed an attempt by a group of Know-Nothings and Pennsylvania Republicans to swing the contest behind a Democratic speaker who would permit an upward tariff revision in place of the antislavery Sherman. The Democratic refusal to budge on the tariff and the inability of the Republicans to produce a majority for Sherman forced the compromise to occur on slavery. In early February 1860 Sherman withdrew in favor of William Pennington of New Jersey, a relatively unknown freshman Republican who signaled he would make modest accommodations toward the southern slave-owners. Sherman received the chairmanship of the House Ways and Means committee as consolation, and promptly tasked Morrill to produce an overhaul of the tariff schedule.[12]

Drawing upon a bill he had drafted over the course of the previous year, Morrill introduced what he described as “an orderly protective tariff” in March 1860. In addition to an upward revision of most rates, the product was something of a special interest free-for-all even as Morrill publicly claimed otherwise. Between December 1858 and March 1860, Morrill was inundated with letters from manufacturers and industrialists requesting favorable protective tariff rates against their foreign competitors. Many of these petitions were copied verbatim into the text of the tariff bill. [13] The Morrill schedule also replaced the ad valorem schedule system of Walker with the reintroduction of item-by-item rates. The new schedule utilized an ad hoc mixture of individual ad valorem rates and specific duties, assessed by import units rather than volume, making its administration less transparent. While it is difficult to measure the full effect of the revisions given this change of assessment, Morrill’s equivalent rates pushed most items well above the 1846 schedule and, in several instances, to near-parity with the Black Tariff levels of 1842. [14]

The Morrill Tariff easily passed the House on May 10, 1860 on a vote of 105 to 64. The issue divided the chamber almost strictly on north-south sectional lines. Its advance was quickly halted in the Senate however, where Robert M. T. Hunter still chaired the Finance Committee. Hunter promptly tabled the measure, placing a hold on its consideration until Congress reconvened as a lame duck body in December. While this roadblock was anticipated by tariff supporters and opponents alike, it had the unintended effect of scheduling the tariff debate’s resumption in the middle of what would become the famous Secession Winter session of Congress.

Though locked in a stalemate again on the national level, the tariff issue actually played an important regional role in the 1860 election. As the Democratic Party divided into two factions over slavery, the Republicans assembled an eclectic anti-slavery coalition by appealing to a list of regional and secondary issues. Newspaperman Horace Greeley described this strategy in a letter outlining the characteristics of a winnable campaign:

I want to succeed this time, yet I know the country is not anti-Slavery.It will only swallow a little anti-slavery in a great deal of sweetening.An anti-slavery man per se cannot be elected; but a tariff, river and harbor, Pacific railroad, free homestead man may succeed although he is anti-slavery. [15]

The selection of Abraham Lincoln, an anti-slavery former congressman who described himself as an “old Henry Clay tariff whig,” almost perfectly fit Greeley’s prescription for the Republican ticket. [16] While Lincoln was presciently averse to leading a national campaign on the tariff issue to avoid alienating the free trade Bryant faction of the party, Hunter’s roadblock in the Senate had inadvertently provided the Republicans with an opportunity to secure the critical swing state of Pennsylvania and, with it, the presidency.

As historian Reinhardt Luthin noted, by mid-1860 the tariff issue “mounted to a fever heat” in Pennsylvania. [17] A Carey-backed Pennsylvania delegation to the Republican Convention in Chicago secured a platform plank endorsing a tariff adjustment to certain “imports as to encourage the development of the industrial interests of the whole country.” The state’s favorite son candidate Simon Cameron also reportedly released his delegates to Lincoln at a strategic moment after receiving assurances that the eventual nominee would be a tariff man.[18]

Over the summer and fall, the Republicans strategically cultivated the tariff issue in Pennsylvania, as well as the manufacturing districts of New Jersey that lay opposite of Philadelphia. Morrill and Sherman stumped throughout the mid-Atlantic in September at the invitation of the Republican National Committee, which noted that their “tariff record will help us.” [19] Lincoln also dispatched his campaign manager David Davis to deliver a package of his old tariff speeches to Cameron, Representative Thaddeus Stevens, and other Republican leaders in the state. The state Republican campaign director then selectively released excerpts to pro-tariff newspapers, intentionally avoiding a mistake that sank Clay’s campaign in 1844 when his tariff remarks were disseminated nationally.[20]

The strategy ultimately worked. The Republicans carried Pennsylvania and split the electoral vote in neighboring New Jersey to secure the White House.

The Tariff and the Secession Winter

The tariff issue’s role in the secession crisis was largely analogous to the tossing of another can of gasoline onto a raging, slavery-fueled fire. Despite later claims of preeminence in the postwar Lost Cause literature, the tariff was never more than an ancillary grievance added to the litany of secessionist charges against the incoming Republican Party’s positions on slavery in the territories, the weakened federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, and the south’s rapidly diminishing position in the United States Senate. But neither was the tariff absent from the discussion.

In South Carolina and the six additional Deep South states that seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration, the perceived threat to slavery alone provided a sufficient pretext for separation in the mind of most delegates, as evidenced in their public declarations. The tariff question lingered in the background of several conventions though. The impending consideration of the Morrill bill in the Senate sparked a flurry of invocations of the Nullification Crisis precedent from 1832. Robert Barnwell Rhett, one of the primary architects of the South Carolina convention, fueled this charge through his arguments before the convention as well as the editorial pages of his newspaper, the Charleston Mercury. Describing the Morrill bill as the “next mammoth swindle on the docket” of the northern Congress, he contrasted this state of affairs with the provisional Confederate government in Montgomery. The latter had the opportunity to pursue “the principle of perfect free trade with all the world,” thereby undermining the protected northern market and eventually compelling its acquiescence in a reciprocal trade liberalization. [21]

Rhett was a veteran firebrand of the earlier nullification battle and proceeded to adapt its lessons and precedents to the constitutional theory of secession that the convention later adopted. In a lengthy public “Address to the Slaveholding States” that he drafted on behalf of the convention, Rhett recounted the role of taxation in the American Revolution and drew analogy between to the present situation of the secessionists, now “taxed for the benefit of the Northern States.” “[T]he consolidation of the North, to rule the South,” he continued, “by the tariff and slavery issues, was in the obvious course of things.” [22]

Robert Toombs advanced a similar argument before the secession convention of neighboring Georgia, again attaching the tariff issue to the slave-owner’s cause and invoking the nullification precedent. In describing the current state of affairs he thundered:

[A]t the last session of Congress they brought in and passed through the House the most atrocious tariff bill that ever was enacted, raising the present duties from twenty to two hundred and fifty per cent above the existing rates of duty. That bill now lies on the table of the Senate. It was a master stroke of abolition policy; it united cupidity to fanaticism, and thereby made a combination which has swept the country. There were thousands of protectionists in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New-York, and in New-England, who were not abolitionists. There were thousands of abolitionists who were free traders. The mongers brought them together upon a mutual surrender of their principles. The free-trade abolitionists became protectionists; the non-abolition protectionists became abolitionists. The result of this coalition was the infamous Morrill bill - the robber and the incendiary struck hands, and united in joint raid against the South. [23]

Not all southerners subscribed to this forging of a link between the two issues. The south had its own industrial pockets and a number of early Confederate tariff discussions saw the makings of a subtle challenge to the doctrinaire free traders of the nullification legacy. Rhett reported some resistance when he pressed other state conventions for a firm free trade commitment. Some months later, factory interests around Richmond made a concerted push to stretch the “incidentally” protective character of the new Confederacy’s “revenue” tariff system. [24] If the south was to industrialize, it would inevitably have to grapple with the political appeal of the old Hamiltonian infant industry argument as manufacturers clamored for insulation from the international market’s competitive pressures.

On the more immediate matter of the Morrill Tariff, hints of dissent emerged over the best strategy to stall the bill’s advance. Georgia’s Alexander Hamilton Stephens, a conditional unionist at the time as well as an old Whig, contested Toombs’ prediction of the tariff’s impending adoption. The Senate, he supposed, could hold back the Morrill bill as Hunter had done if only the southerners would retain their seats. The northern will to impose it, he predicted, was exaggerated given a number of free trade men in New England who had backed the tariff reduction in 1857. [25]

To the extent that it was discussed, the tariff issue remained distant and subordinate to the south’s numerous grievances with the rise of an antislavery political party in the north. Yet Rhett and Toombs carried the argument to a number of strategic political ends. Toombs invoked the tariff precedent again in Georgia’s secession declaration, calling for the settlement of the issue along the lines of the 1846 Walker Tariff. In Florida, a “statement of causes” drafted by Governor Madison Starke Perry charged the north with reviving the tariff to its sectional advantage and “receiving back in the increased prices of the rival articles which it manufactures nearly or quite as much as the imposts which it pays.” [26] Rhett also succeeded at incorporating an express prohibition on protective tariffs in the Confederate constitution, albeit with pockets of resistance that produced an unexpectedly narrow margin of votes at the convention. With the clause secure, he began to articulate a larger strategic purpose to this free trade commitment. By restricting itself to a revenue-only tariff system, the nascent Confederacy hoped to cultivate support and eventually recognition from the European powers through the lure of free trade. As Rhett’s strategy predicted, the Confederate’s use of a low revenue tariff “placed the European nations recognizing our independence and seeking our alliance, in a more lucrative position than the United States had occupied.” [27] Assuming the northern government continued its declared course and adopted the Morrill Tariff, Great Britain would have cause to align with the new Confederacy.

The Morrill tariff bill arrived in the Senate in early December, as per Hunter’s delaying motion from the previous summer. Though unanticipated at the time of the original motion, it was initially subsumed by the more pressing crisis of disunion as moderates on both sides attempted to cobble together a last ditch compromise on the territorial status of slavery to avert separation and, possibly, war. The departure of several southern delegations in late January foretold the failure of a compromise solution to secessionism, yet for the tariff’s backers it also presented an opening to break Hunter’s hold. Without the southern delegations to oppose it, the reconstituted Finance committee resumed work on the bill in late January and advanced it before the full chamber in barely a month’s time. Control of the amendment process fell largely in the hands of Rhode Island Senator James Fowler Simmons. Earlier that year Simmons had collaborated with Morrill to secure a de facto monopoly for a screw manufacturer in his home state through punitive tariff rates against its competitors. With the committee roadblock cleared and the secession crisis occupying the nation’s attention, he resumed the process of stacking the bill with additional legislative favors and carved out dozens of further protections to reward his party’s electoral supporters. [28]

The Morrill Tariff cleared the Senate on March 2, 1861 and was promptly signed into law by President Buchanan. The departure of its southern opponents facilitated an easy vote of approval, though in truth this circumstance likely only hastened its adoption by a few months due to Lincoln’s expected support and additional Republican gains in the incoming Senate. In the Upper South, news of the tariff bill’s expedited approval lent credence to the fire-eater warnings of men like Rhett and Toombs. "Observe the haste they made to adopt a tariff higher than any before known, so soon as they were relieved from the presence of some fourteen Southern Senators and thirty-odd Southern Representatives," raged George Wythe Randolph in a widely noticed speech to Virginia’s secession convention some two weeks later.[29] Yet southerners were not alone in their dissatisfaction with the results. The disunionist movement that facilitated the Morrill Tariff would soon overtake its intended implementation. As Morrill wrote to Sherman on April 1, “Our tariff bill is unfortunate in being launched at this time, as it will be made the scape-goat of all difficulties.” [30] The tariff’s authors had designed it for peacetime implementation that now appeared increasingly out of reach.

Tariff Diplomacy

In December 1861 the British free trade stalwart Richard Cobden penned a letter to one of his frequent trans-Atlantic correspondents, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner. Cobden, who shared in Sumner’s abolitionism, expressed his dismay at the raging conflict in North America:

In your case we observe a mighty quarrel: on one side protectionists, on the other slave-owners. The protectionists say they do not seek to put down slavery. The slave-owners say they want Free Trade. Need you wonder at the confusion in John Bull's poor head? [31]

With British opinion at the time tending to favor free trade and the empire commonly styling itself as a global stalwart in the anti-slavery cause, this unusual parsing of political lines portended one of the first geopolitical complications of the Civil War. Cobden was clearly concerned with the North’s early reluctance to commit itself to the cause of emancipation rather than simply holding the union together. Yet the tariff presented an additional obstacle to the anti-slavery cause. Whereas Britain might have otherwise naturally supported the Union and used its suasion to nudge the latter’s objectives in the antislavery direction that both Cobden and Sumner both desired, the Morrill Tariff of the previous spring had wreaked havoc upon the United States’ commercial relations with Her Majesty’s government.

British opinion came to detest the Morrill Tariff almost immediately upon its enactment. The celebrated British economist William Stanley Jevons would later describe the measure as “the most retrograde piece of legislation that this country has witnessed,” seeing as it had directly reversed the cooperative pattern of Anglo-American trade liberalization initiated in 1846. [32] The London press quickly dubbed it the “Immoral Tariff” on account of this perceived betrayal. In some circles the idea even took hold that the tariff issue had precipitated secession itself, effectively inverting the order of events in which southern departures from the Senate chamber had accelerated the measure’s adoption. [33]

The new Confederate government looked upon this turn of events as a chance to secure much-needed foreign support. As Rhett had predicted, the promise of free trade, and indeed an even lower “revenue” tariff regime than had ever been obtained with the United States, proved an enticing offer for the world’s leading consumer of southern cotton exports. The Confederate government recognized this opportunity and attached an anti-Morrill message in its overtures for diplomatic recognition, effectively turning free trade into a carrot-like enticement to complement the export-restricting stick of its famous and economically flawed King Cotton Diplomacy strategy.

At least at the outset of the war, Britain nibbled. Major newspapers routinely described the American conflict as a tariff war between the protectionist north and free-trade south, often noting Lincoln’s reluctance to commit to emancipation in the process. An unsigned editorial in Charles Dickens’ magazine All the Year Round described the Morrill Tariff as “the last grievance of the South…passed as an election bribe to the state of Pennsylvania.” [34] Confederate sympathizers in Britain led by Liverpool merchant James Spence openly cited the tariff divide to press for diplomatic recognition of the south on the grounds of a promised economic boom from the ensuing trade. To antislavery men such as Cobden and his frequent liberal collaborator in parliament John Bright, this strategically cultivated tariff myth presented a continuous obstacle as they lobbied to steer their government away from diplomatic engagement with the slaveholding republic of the south. It was not until 1863, and in particular Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, that British opinion moved safely beyond the tariff agitation and began to clearly recognize the role of slavery in the conflict. [35] The combination of northern legislative opportunism and southern diplomatic propaganda had effectively distracted a crucial international power for the first two years of the war. Though the Confederate goal of recognition remained elusive, tariff-induced sympathy with the south played no small role in sustaining Britain’s official neutrality and willingness to engage commercially with the southerners.

Civil War Tariffs in Retrospect

For the northern government’s diplomatic objectives, as Cobden and Bright continuously reminded Sumner, the Morrill Tariff had been a shortsighted strategic blunder. It unintentionally alienated an otherwise natural anti-slavery ally for what could, at best, be described as short term economic favors to a few politically connected firms and industrialists. The Confederacy eagerly exploited this misstep in its unsuccessful quest for diplomatic recognition, yet in doing so also elevated the tariff cause from its role as an ancillary secessionist grievance to a centerpiece of Lost Cause historiography.

With the slavery question settled by the war and increasingly recognized as the Confederacy’s intractable moral stain, the tariff issue obtained significantly greater prominence in the postwar reminiscence literature than the secession debates themselves. Though he did not completely sidestep slavery, Jefferson Davis, in his monumental history of the Confederate government, would describe the tariff issue as “the most prolific source of sectional strife and alienation” between the drafting of the United States Constitution and the Civil War. [36] Albert Taylor Bledsoe, an early “Lost Cause” pamphleteer, raised the tariff issue to parity with slavery in his postwar depiction of the conflict’s causes, at times even suggesting the tariff’s preeminence. [37] What started as a lesser secessionist grievance, only to be adapted into a somewhat diversionary diplomatic tactic with Britain, returned as a rationalized “memory” in the postbellum sorting of the war’s physical destruction and slavery’s moral baggage. While most historians give little credence to post hoc tariff accounts of the Confederacy’s formation, they have in part shaped a handful of later interpretations of the war, particularly the economic causality arguments of Charles A. and Mary Beard.[38]

The Morrill Tariff itself was unexpectedly short lived, though highly influential upon subsequent American trade policy. Intended for peacetime operation, its main protective provisions were quickly obscured by the economic mobilization of the war. Congress amended its rates twice in 1861 to augment the tariff’s revenue features as a war finance device, though both measures increased the overall level of taxation. Larger historical significance may be traced to the Morrill Tariff as a turning point, as it inaugurated 52 years of high tariff protectionism as a national economic policy in the United States. Whereas antebellum tariff battles saw the country pivot between competing regimes of protection and relatively free trade, the Civil War inaugurated a semi-permanent political ascendance of the tariff’s industrial beneficiaries in the Gilded Age. Traditional free trade constituencies in the absent and then politically weakened south, along with the agricultural west, were unable to regain the upper hand until the Woodrow Wilson administration. As a result of its settlement in 1861 and its wartime entrenchment, the tariff remained the dominant topic of American economic policy until the eve of the First World War.

- [1] Author’s calculations from U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1975), published as H.R. Rep. No. 93-78 (Parts 1 and 2) (1975).

- [2] Phillip W. Magness "Constitutional tariffs, incidental protection, and the Laffer relationship in the early United States," inConstitutional Political Economy20.2 (2009):177-92.

- [3] Alexander Hamilton, Report of The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, On The Subject of Manufactures. Presented to The House of Representatives, December 5, 1791, 2nd ed. (Dublin: Reprinted by P. Byrne, 1792), first printed in folio format in Philadelphia in 1791.

- [4] Phillip W. Magness "The American System and The Political Economy Of Black Colonization,"in Journal of the History of Economic Thought37, no. 2 (2015): 187-202.

- [5] R.A. McGuire and T. Norman Van Cott. "A supply and demand exposition of a constitutional tax loophole: The case of tariff symmetry," in Constitutional Political Economy14, no. 1 (2003): 39-45.

- [6] John Taylor of Caroline Tyranny Unmasked, Liberty Fund 1992 ed. (Washington D.C.: Davis & Force, 1822), 100.

- [7] William W. Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836 (Oxford University Press, 1966), 257.

- [8] “Exposition & Protest,” in Ross M. Lence, ed.,Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun. (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1992).

- [9] James K. Polk to J. K. Kane, June 19, 1844, James K. Polk Papers, Library of Congress.

- [10] Scott C. James and David A. Lake. "The second face of hegemony: Britain's repeal of the Corn Laws and the American Walker Tariff of 1846," in International Organization43, no. 1 (1989): 1-29.

- [11] Henry Charles Carey,Principles of Social Science (Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott & Company, 1867).

- [12] Richard F. Bensel, Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859–1877 (Cambridge, UK, 1995), 50–56; Phillip W. Magness, "Morrill and the Missing Industries: Strategic Lobbying Behavior and the Tariff, 1858–1861,"in Journal of the Early Republic29, no.2 (2009), 293.

- [13] Magness, “Morrill and the Missing Industries,” Tables 1 & 2.

- [14] Ibid., Table 3.

- [15] Horace Greeley to Margaret Allen, January 6, 1860, quoted in Reinhard H. Luthin "Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff,"in The American Historical Review 49, no. 4(July 1944):615.

- [16] Abraham Lincoln to Edward Wallace, October 11, 1859, in Roy Prentice Basler, ed.The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 10 vols. (Rutgers University Press, 1955), 3:487.

- [17] Luthin "Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff," 614.

- [18] Hawkins Taylor to John Allison, December 21, 1860, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.

- [19] J. Wilson to Morrill, Sept. 15, 1860, Justin Morrill Papers, Library of Congress.

- [20] William M. Reynolds to Abraham Lincoln, July 25, 1860; David Davis to Lincoln, Aug. 5, 1860; Thomas H. Dudley to Davis, Sept. 17, 1860; and ‘‘Tariff scraps’’ in Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress.

- [21] “Our Washington Correspondence,” February 4, 1861, and “The Southern Congress and Free Trade,” February 5, 1861, Charleston Mercury.

- [22] Robert Barnwell Rhett, “The Address of the People of South Carolina, Assembled in Convention, to the People of the Slaveholding States” (Charleston: Evans and Cogswell, Printers, 1860).

- [23] William W. Freehling and Craig M. Simpson, eds.Secession Debated: Georgia's Showdown in 1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 37-38.

- [24] Jay Carlander and John D. Majewski, "Imagining ‘A Great Manufacturing Empire’: Virginia and the Possibilities of a Confederate Tariff,"in Civil War History49, no. 4 (December 2003): 334-52.

- [25] Freehling and Simpson, Secession Debated, 63

- [26] Georgia Secession Convention, “Declaration of Causes,” January 29, 1861, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_geosec.asp accessed April 9, 2016; Madison Starke Perry Papers, State Archives of Florida, Series 577, Carton 1, Folder 6.

- [27] Robert A. McGuire and T. Norman Cott, "The Confederate constitution, tariffs, and the Laffer relationship,"in Economic Inquiry40, no. 3 (July 2002): 428-38; Robert Barnwell Rhett, and William C. Davis, eds.,A Fire-eater Remembers: The Confederate Memoir of Robert Barnwell Rhett. (University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 28, 33-35.

- [28] Magness, “Morrill and the Missing Industries,” 306.

- [29]William W. Freehling and Craig M. Simpson, eds.,Showdown in Virginia: The 1861 Convention and the Fate of the Union (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 51-52.

- [30] Justin S. Morrill, ‘‘Letters From My Political Friends,’’ in The Forum 24 (Sept. 1897–Feb. 1898), 146.

- [31] John Atkinson Hobson, Richard Cobden: The International Man (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1919), 350.

- [32] William S. Jevons, The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and Probable Exhaustion of Our Coalmines (London: MacMillan & Co., 1866), 326.

- [33] Marc-William Palen, "The Civil War's Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate and the Confederacy's Free Trade Diplomacy,"in The Journal of the Civil War Era3, no. 1 (March 2013): 35-61.

- [34] “The Morrill Tariff,” All the Year Round, December 28, 1861.

- [35] Palen “Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate”.

- [36] Jefferson Davis. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 2 vols. (New York: Appleton and Company, 1881), 1:498.

- [37] Albert Taylor Bledsoe,Is Davis a traitor; or, Was secession a constitutional right previous to the war of 1861? (Baltimore: Printed for the Author by Innes & Company, 1866), 242-5.

- [38] Charles A. and Mary Beard, The Rise of American Civilization, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1933), 1:36-38.

If you can read only one book:

Taussig, Frank William. The Tariff History of the United States. New York/London: G. P. Putnam's sons, 1888.

Books:

Freehling, William W. Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

Magness, Phillip W. “Morrill and the Missing Industries: Strategic Lobbying Behavior and the Tariff, 1858–1861," in Journal of the Early Republic 29, no. 2 (2009): 287-329.

Palen, Marc-William. "The Civil War's Forgotten Transatlantic Tariff Debate and the Confederacy's Free Trade Diplomacy," in The Journal of the Civil War Era 3, no. 1 (2013): 35-61.

Luthin, Reinhard H. "Abraham Lincoln and the Tariff." The American Historical Review 49 no.4 (July 1944): 609-29.

Northrup, Cynthia Clark, and Elaine C. Prange Turney, eds. Encyclopedia of Tariffs and Trade in US History, 3 vols. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Palen, Marc-William. “The Great Civil War Lie.” New York Times – Opinionator, June 5, 2013, discusses the effect of the Morrill Tariff on initial British sympathy for the Confederate cause.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.