The Abolitionist Movement

by Julie Holcomb

Beginning with isolated, individual critics of slavery, antislavery rhetoric gained momentum in the mid-eighteenth century as colonial Quakers questioned the relationship between Christianity and slaveholding. In the revolutionary era elite white men organized societies in opposition to the slave trade. Early activists believed the abolition of the international slave trade would in time lead to the abolition of slavery. In contrast, antebellum abolitionism brought together a broad array of reformers — black and white, male and female, religious and secular — to work for immediate, sweeping political and social change. Radical Garrisonian abolitionists clashed with more conservative abolitionists over questions of strategies and tactics as well as issues of gender and race. In the 1810s and 1820s, a series of slave revolts rocked the Atlantic world. These rebellions coincided with renewed antislavery debate in the United States and Great Britain. Antislavery activists proposed colonization, establishing an American colony in Africa for freed slaves and free blacks, as a safe alternative to emancipation. Immediatism, or the immediate abolition of slavery, originated in the anti-colonization movement and agitation from immediatists resulted in Britain abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833. In contrast to the British abolitionist movement, the American abolitionist movement took more than forty years and a bloody civil war to achieve slave emancipation. William Lloyd Garrison published the inaugural issue of The Liberator in January 1831, which is often cited as the beginning of a new, radical abolitionist movement in America. One year later, in 1832, Garrison helped found the New England Anti-Slavery Society, the first of many antislavery organizations to take an uncompromising stand against slavery. In May 1840 American abolitionists split over the question of strategies and tactics. Garrison and his supporters retained control of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison and the AASS maintained a broad reform platform, including women’s rights. Conservative members of the AASS, led by brothers Lewis and Arthur Tappan, formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFASS) after the brothers and three hundred supporters left the AASS. The Tappans and their supporters claimed other reform movements threatened the antislavery cause, which had to remain orthodox and compatible with traditional cultural norms such as the proper role of women in society. In the 1850s the organized abolitionist movement was eclipsed by the growing political crisis in the United States. The coming of war in 1861 re-energized the American abolitionist movement. For abolitionists, the coming of the Civil War was the culmination of a decades-long struggle for the slave’s freedom. Adoption of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment two years later assured abolitionists that their struggle, and the slave’s fight, had truly reached a successful conclusion.

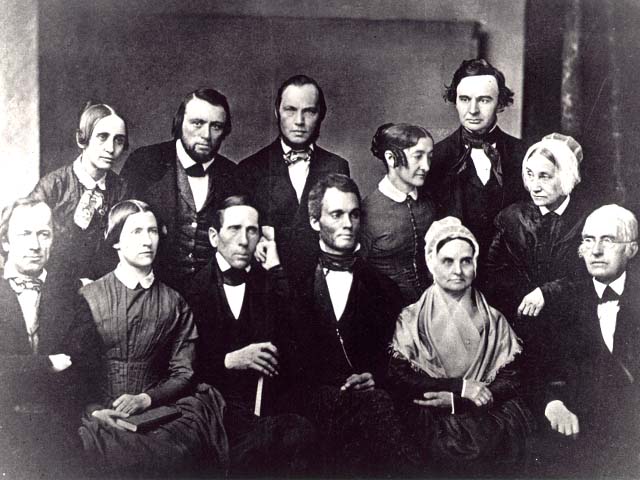

Executive Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society 1851

Image Credit: Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

The abolitionist movement predates the American Revolution. Abolitionism is commonly associated with the radical, nineteenth-century Boston printer and editor, William Lloyd Garrison. Yet, the abolitionist movement had much more patrician origins. Beginning with isolated, individual critics of slavery, antislavery rhetoric gained momentum in the mid-eighteenth century as colonial Quakers questioned the relationship between Christianity and slaveholding. In the revolutionary era elite white men organized societies in opposition to the slave trade. Early activists believed the abolition of the international slave trade would in time lead to the abolition of slavery. In contrast, antebellum abolitionism brought together a broad array of reformers — black and white, male and female, religious and secular — to work for immediate, sweeping political and social change. Radical Garrisonian abolitionists clashed with more conservative abolitionists over questions of strategies and tactics as well as issues of gender and race. In the 1840s the movement splintered. Still abolitionism remained a viable movement for social change through the American Civil War.

Abolitionism began in the eighteenth century, originating in secular and religious ideas that emphasized individual responsibility. The political philosophy of the Enlightenment emphasized natural law and human rights while the evangelical fervor of the Great Awakening stressed conversion by rejecting sin and embracing God’s salvation. Salvation was no longer predetermined by an unknowable God. Thus individuals were to live according to their Christian morals, taking responsibility for their own actions. Enlightenment philosophy and Christian evangelicalism provided an important ideological foundation for the early abolitionist movement. Among the first Protestant groups to reject the Calvinist doctrine of predestination was the Society of Friends, or Quakers, which was established in the seventeenth century in the wake of the English Civil War.[1]

The Society of Friends believed all individuals could experience the Inner Light, or the voice of God. Quakers emphasized a personal, mystical relationship with God, making choices that aligned with the fundamental precepts of the Inner Light. Quakers rejected intermediaries such as priests, sacraments, and offerings, believing such trappings interfered with the individual experience of the Inner Light. Moreover, Quakers emphasized the brotherhood of man and refused to adopt social graces that symbolized recognition of authority such as removing one’s hat or using titles to address social superiors. Quakers also renounced violence, even so called just wars, because physical violence and coercion were contrary to the Inner Light. Quakers’ emphasis on the Inner Light provided the moral foundation for their criticism of slaveholding.

Quaker abolitionism did not gain momentum until the mid-eighteenth century, when in the midst of the political crisis of the Seven Years’ War, Pennsylvania Quakers withdrew from participation in the colonial government rather than support the wars against the French and their Native American allies. Political crisis led many Friends to accept the ministry of Quaker reformers like Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, who believed the political crisis was a moral crisis rooted in Friends’ continued support of slavery.

In the mid-eighteenth century colonial Quakers led the development of Quaker antislavery ideology in North America as well as Great Britain. In 1754 Woolman published Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes, which circulated extensively in the American colonies as well as in England. Woolman claimed the golden rule applied to all, thus slavery violated the Christian principles of universal brotherhood. In the 1750s many North American Quaker meetings, including the influential Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, took action against slaveholding by Friends. By 1775 most American Quakers had freed their adult slaves and made slaveholding an offense punishable by disownment. In England, London Yearly Meeting banned Friends’ participation in the slave trade in 1761. Some American Quakers including Woolman and Benjamin Lay also urged Friends to stop using the products of slave labor, describing such goods as “prize goods” that had been seized by force. Antislavery Quakers like Benezet, Woolman, and Lay had limited influence outside the Society of Friends until the 1760s when the political crisis between the American colonies and England became acute. Opponents of slavery used the revolutionary climate to link the causes of American colonial independence to the fight for the abolition of the slave trade and slavery. In America, critics of slavery and the slave trade formed organizations for the gradual abolition of slavery.[2]

Anthony Benezet and other prominent Philadelphians established the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS) in 1775. The PAS met regularly, organizing the antislavery activities of Friends and others. The PAS aided free blacks in court, drafted legislative petitions, and solicited and distributed reports from various committees about antislavery activities. At the height of the American Revolution, the PAS suspended its activities. Benezet and other members re-established the organization in 1785. Four years later, in 1789, the Pennsylvania General Assembly incorporated the PAS, granting it state sanction much like any other business.

The New York Manumission Society (NYMS) organized in 1784. Like the PAS, the NYMS advocated gradual abolition, established schools for free blacks, provided legal assistance to free blacks in court, and fought to end the domestic and international slave trade. The NYMS received state incorporation and counted among its membership Quakers, who comprised more than fifty percent of its members. The NYMS’s most enduring legacy was the schools the society established for free blacks. Many influential antebellum black abolitionists, including Henry Highland Garnet, Alexander Crummel, and Samuel Ringgold Ward, graduated from NYMS-sponsored schools.

In 1794 abolitionists established the American Convention of Abolition Societies to serve as a central clearinghouse for antislavery strategies and tactics. Unlike the PAS and the NYMS, the American Convention gave the movement national scope. The Convention met biennially from 1794 until its dissolution in the 1830s. The Convention led a petition drive in the 1790s, urging Congress to abolish the slave trade. But the Convention struggled with other problems such as the admission of slaveholders into its membership. As a result, the Convention failed to become the effective national protest organization that reformers sought.

Compared to the second generation societies of the 1830s, the activists who joined the PAS, the NYMS, or the American Convention appear strikingly conservative. All three associations emphasized legislative action, gradual emancipation, and the abolition of the slave trade. Eighteenth-century abolitionist societies worked within local, state, and national laws and used the influence of their members’ social positions to bring about the abolition of the slave trade. These early abolitionists believed that abolition of the slave trade would accelerate the movement for the abolition of slavery. Not surprisingly, when the international slave trade was abolished by Britain in 1807 and the United States in 1808, the abolitionist movement waned until 1816 and the founding of the American Colonization Society. The founding of the ACS, the rise of black activism in the 1810s, and the tremendous social, economic, and religious upheavals of the early nineteenth century all framed the development of radical abolitionism.

In the 1810s and 1820s, a series of slave revolts rocked the Atlantic world. Rebellions in the British colonies of Barbados (1816), Demerara (1823), and Jamaica (1831-1832) had a transformative effect on parliamentary debates about colonial slavery. Slaves in the United States were equally restive. In 1822 authorities in Charleston, South Carolina, uncovered evidence that former slave Denmark Vesey planned to lead a massive slave rebellion in the United States. And in 1831, Nat Turner led the bloodiest slave revolt in antebellum America, resulting in the deaths of nearly sixty whites in Southampton County, Virginia. These rebellions coincided with renewed antislavery debate in the United States and Great Britain, a connection not lost on white slaveholders who were convinced of an abolitionist plot to incite rebellion. In the United States, for example, Nat Turner’s rebellion occurred within two years of the publication of the Appeal written by black militant David Walker.[3]

In his Appeal Walker, a free black from the South, urged slaves to revolt against their masters. Born in 1796 or 1797 in Wilmington, North Carolina, to a slave father and a free black mother, Walker traveled throughout the country before settling in Boston, Massachusetts. Free, as a result of his mother’s status, Walker had witnessed the horrors of slavery. He joined with other black activists in the fight against slavery. Walker was a frequent contributor to Freedom’s Journal, the first African American newspaper. In 1829 he published his Appeal, urging blacks to embrace if necessary armed resistance against whites. Appeal went through at least three editions between 1829 and 1831. Walker’s familiarity with black communication networks helped him distribute his pamphlet throughout the South despite white resistance. For many southern whites, the thorough distribution of Walker’s Appeal and the timing of Turner’s rebellion evidenced the close connection between abolitionist agitation and slave rebellion, an idea first discussed by Bryan Edwards in 1797 after the Haitian Revolution.[4]

Edwards, a West Indian planter and a Member of Parliament, blamed French abolitionists for the slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Edwards’ Historical Survey of the French Colony of St. Domingo was disseminated widely throughout the Atlantic world and reprinted in numerous editions well into the nineteenth century. His was the standard pro-slavery account of the slave rebellion. Pro-slavery supporters in the United States and Britain transformed Edwards’s history into a general theory about the relationship between abolitionist agitation and slave rebellion. Slave rebellions, they argued, were not the result of the abuses of slavery. Rather slave rebellions were the result of meddling abolitionists.[5]

Antislavery activists proposed colonization as a safe alternative to emancipation. In 1817 activists organized the American Colonization Society (ACS), to promote the establishment of an American colony in Africa for freed slaves and free blacks. Pro-colonizationists linked the potential for slave revolt to the presence of a large free black population, claiming slaveholders would be encouraged to free their slaves if those freed slaves were sent to Africa. Emigration would reduce the population of free blacks in the United States, especially in the South. Moreover, colonizationists claimed emigration to Africa would resolve racial problems and provide racial uplift. African Americans, colonizationists argued, could never attain equality in a white society. Initially, some black abolitionists supported the ACS. However, many abolitionists regardless of race came to believe that the ACS was anti-black rather than anti-slavery. David Walker, for example, condemned colonization schemes as a white supremacist hoax.

Some abolitionists tried to find common ground between pro- and anti-colonizationists. Benjamin Lundy, editor of the weekly antislavery newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation, supported gradual emancipation and limited colonization schemes in Haiti and Texas, but did not support the ACS. However, by the early 1830s even Lundy came to realize that colonization would not lead to abolition. The colonization movement’s popularity in the 1820s led black abolitionists to organize anti-colonization groups. This organizational activity had a significant impact on the antislavery societies that formed in the 1830s.[6]

Wide-scale black activism in the 1810s and 1820s was just one of many changes transforming American society in the early nineteenth century. The development of a new economic order based on large-scale manufacturing and trade, competition, consumption, and cash exchange altered the way goods were produced. Prior to the introduction of the factory system, manufacturing had been completed in home-based artisanal workshops with master and apprentice working side by side. As industrialization gained momentum in New England and elsewhere in the North, workshops were replaced by small mills that were later replaced by large factories, converting labor into an impersonal market commodity.

Industrial capitalism influenced the development of an urban working class and the formation of new urban middle class. Economic instability increased across the American social spectrum. Men and women worked in town in factories, offices, or in other urban professions such as domestics in middle- and upper-class homes. What had once been a personal relationship between a master or mistress, on the one hand, and his or her servant, on the other, became an impersonal commodity-based relationship that often pitted the two groups against each other. Industrialization created distinct divisions between the working and middle classes. Middle-class men and women, for example, enjoyed increased leisure time. In contrast, working-class men and women often struggled in the new economy. Rather than live off the land in difficult times as men and women did in an agricultural society, working-class men and women were dependent on cash wages. As a result, their financial well-being ebbed and flowed with the economy. Tensions between the classes were exacerbated by the steady influx of immigrant labor into the urban North.

Social tensions further increased as universal suffrage became the norm throughout the North. After 1815, states began to revoke property qualifications for voting and holding elected office. Still, suffrage was generally extended only to white males as states limited, or even revoked political rights for black men and all women. The expansion of political rights transformed spectators into citizens as more and more eligible voters turned out at the polls.

The Second Great Awakening emerged in part as the result of these sweeping changes in American society. Revivalist ministers Charles G. Finney and Lyman Beecher encouraged followers to seek a more personal relationship with God. Sin was the result of selfish choices made by men and women who possessed free will and could choose otherwise. Social evils such as drunkenness, lewd behavior, intemperance, and poor work habits were the result of the collective sinfulness of American society.[7]

Social movements such as abolitionism were seen as key to reforming American society. Religious converts formed movements to reform and educate Americans including educational reform, penal reform, temperance, women’s rights, moral reform, and abolitionism. Regardless of race, gender, or class, reformers came together in local, regional, and national organizations to redeem American society. Of these antebellum reform movements, abolitionism was the most established. But antebellum abolitionism, in many ways, shed its eighteenth-century patrician roots to become the most controversial movement of the nineteenth century as abolitionists, influenced by black activism and evangelical fervor, began to call for the immediate abolition of slavery.

Immediatism, or the immediate abolition of slavery, originated in the anti-colonization movement; however, immediatism was further refined by the renewal of British abolitionism in the mid-1820s. In 1824 British Quaker Elizabeth Heyrick published Immediate Not Gradual Abolition. Calling for grassroots participation in the abolitionist movement, Heyrick urged men, women, and even children to boycott the products of slave labor especially West Indian sugar. Heyrick’s tract used the Quaker tactic of boycotting of slave labor; yet she added a new twist, linking the rejection of slave-labor products to the immediate abolition of slavery. Reprinted in the United States soon after its British publication, Heyrick’s Immediate Not Gradual Abolition became the most influential abolitionist tract of the antebellum period.[8]

Heyrick’s tract provided momentum to a renewed British abolitionist movement. Initially, leading British abolitionists called for gradual, compensated emancipation. Compensation, in this argument, would go to the slaveholders. By 1831, however, British abolitionists adopted the immediatist argument promulgated by Heyrick. In 1833, as a result of abolitionist agitation, Parliament passed the Emancipation Act, abolishing slavery in the colonies on August 1, 1834. In a compromise measure, the act also established an interim apprenticeship system, which would end in 1845. Five years later, under tremendous public pressure, Parliament amended the Emancipation Act and ended apprenticeship as of August 1, 1838.

In contrast to the British abolitionist movement, the American abolitionist movement took more than forty years and a bloody civil war to achieve slave emancipation. The British abolitionist movement was an important influence on the American movement. Immediate Not Gradual Abolition, for example, united American abolitionists who had grown dissatisfied with the status quo. However, there were significant differences between the two countries that affected the progress of abolition. In Britain, the abolitionist movement became a mainstream movement, representing the political views of most though not all Britons. In the United States, abolitionists were unable to shake their reputation as a troublemaking minority. Despite these differences many American abolitionists attempted to transplant British success to American soil, often with frustrating results.

In the late 1820s American Quakers, including James and Lucretia Mott, and free blacks formed free produce societies. Boycotting slave-labor goods such as cotton and sugar was promoted as both a moral and a practical, economic response to slavery. Benjamin Lundy’s newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation highlighted news of British abolitionists’ efforts, including reprints of Immediate Not Gradual Abolition and other British tracts. To promote female readership, Lundy hired young Quaker writer Elizabeth Margaret Chandler. The Ladies’ Repository, under Chandler’s editorship, carried news of ladies’ free produce societies as well as poetry and other sentimental literature. Lundy also hired another young writer and editor, William Lloyd Garrison.

Garrison and Lundy had met as a result of their shared interest in the American Colonization Society (ACS). Both men were influenced by Immediate Not Gradual Abolition. And both men had become disillusioned with the ACS. Lundy, however, never fully gave up on the idea of establishing a free colony for blacks. In contrast, when Garrison left the ACS, he gave up the colonization idea and fully embraced immediate abolitionism. The two men worked together on the Genius throughout the late 1820s, dissolving their partnership in 1830.

In January 1831 Garrison published the inaugural issue of The Liberator, which is often cited as the beginning of a new, radical abolitionist movement. Yet it is important to remember that Garrison was deeply influenced by the early antislavery activism of the Quakers, black resistance to slavery and to the ACS, and the work of women such as Elizabeth Heyrick. In language that echoed the Second Great Awakening, Garrison denounced slavery as a sin against God. All slaveholders were therefore sinners. The abolition of slavery had to begin without delay. Garrison condemned the ACS, arguing that the racist spirit of the ACS assumed that whites and blacks could not live together. As evidence, Garrison cited the society’s own statements of horror at the prospect of a large free black population should slavery be abolished without colonization. Reflecting the influence of black activists, the more radical members of the antebellum abolitionist movement called for racial equality as well as the abolition of slavery.[9]

One year later, in 1832, Garrison helped found the New England Anti-Slavery Society, the first of many antislavery organizations to take an uncompromising stand against slavery. In 1833, abolitionists from nine states met in Philadelphia to organize the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). Among the delegates to the founding convention were several prominent black abolitionists including Robert Purvis (founder of the Colored Free Produce Society) and James McCrummell. Garrison and a committee of other delegates wrote the AASS’s Declaration of Sentiments. Quaker abolitionist Lucretia Mott suggested important revisions to the final document. Adoption of the Declaration affirmed supporters’ break with colonization and other gradualist measures and their commitment to immediatism and racial equality.

In the days following the AASS convention, Mott called on McCrummell to assist in founding the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). One year earlier, in 1832, black women in Salem, Massachusetts, had formed the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, and in 1833 women in Boston formed the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. The PFASS, however, outlasted all other women’s antislavery societies, remaining active until 1870. At its peak, the PFASS exceeded two hundred members although a core group of women ran the society. The PFASS challenged gender norms, bringing women into the public arena in the debate over slavery. Moreover, the interracial character of the society invoked fears of “amalgamation” (miscegenation) and social equality. By the mid-1830s, the women of the PFASS were at the center of the debate about women’s proper place in the public sphere.

In the 1830s, abolitionists used a number of tactics to promote their cause. In 1835 abolitionists organized a postal campaign targeting ministers, politicians, and newspaper editors throughout the South. Reformers flooded the South with thousands of pieces of abolitionist literature, believing that once convinced of the world’s hostility to slavery, slaveholders would voluntarily end slavery. Instead, abolitionists’ postal campaign sparked a wave of mob violence throughout the North and the South. In 1835 angry residents of Charleston, South Carolina, broke into the post office and confiscated the abolitionist literature, which they later burned along with an effigy of William Lloyd Garrison. That fall, in Boston, a mob looking for British abolitionist George Thompson instead found Garrison and dragged him through the streets. In 1837 anti-abolitionist mobs targeted the printing press of Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois. Lovejoy and his supporters gathered in his office to protect his press from the mobs. When the mobs set the building on fire, Lovejoy ran from the building and was shot and killed, making him the abolitionist movement’s first martyr.

In 1835 abolitionists also began an intensive national antislavery petition campaign. Abolitionists had petitioned Congress for an end to slavery in Washington, D.C. and an end to the interstate slave trade. The national campaign that launched in 1835 emphasized local effort. Volunteers, many of them women, went door to door gathering signatures on antislavery petitions. For many supporters of abolitionism, the petition campaign was an opportunity to become involved in the movement without having to face down an angry mob. By May 1838 the AASS had sent more than 415,000 petitions to Congress. More than half of those petitions bore the signatures of women.

No Congressional action was taken on these petitions. They were automatically tabled as a result of the “gag rule,” which was implemented in 1836. The “gag rule” was passed at the height of the antislavery violence. Northern and southern politicians hoped to calm sectional hostilities by refusing to debate any antislavery petition. Instead of easing sectional tensions, the “gag rule,” which remained in force until 1844, accelerated the growing sectionalism of American politics and did much to politicize the abolitionist movement.[10]

In the 1820s American women organized free produce societies; in the 1830s many of these same women organized antislavery societies. Abolitionism held particular appeal for women, regardless of race. Slavery violated accepted ideas of family and gender relations; slavery encouraged the sexual abuse of slave women and violated familial bonds. The misuse of the enslaved female body paralleled the misuse of free female bodies. Despite a shared sisterhood that attempted to transcend race, black and white female abolitionists often adopted different attitudes toward abolitionism. White women emphasized moral suasion in their abolitionism. Many white women also held conservative views about racial equality. In contrast, African American women focused on a broader agenda, including racial uplift alongside abolitionism.

At first glance, women’s involvement in free produce and antislavery societies appears to mark the beginning of female involvement in social causes. However, women had been involved in benevolent work since the 1790s, caring for widows and orphans, assisting the aged, and providing medical care for pregnant women. Like eighteenth-century men’s antislavery societies, women’s benevolent organizations followed a deferential style of politics, relying upon private influence to gain financial and political support for their organization’s work. Moreover, benevolent organizations focused on improving the moral character of the individual and promoting social order.

In contrast, antebellum women’s reform groups, including antislavery societies, drew from more varied racial and economic backgrounds. For example, women’s groups were biracial, segregated, or integrated in their membership. Women joined for a variety of reasons including upper-class noblesse oblige, religious convictions, hatred of racism and slavery, or the influence of family and friends. Women reformers sought political support from a larger group of politicians and citizens, relying on controversy and publicity to promote their work and bring about broad social change. Significantly, women reformers called on women to identify as women with fallen, poor, or enslaved women. This was a radical change from the benevolent, maternalistic style of earlier women’s organizations.

By the mid-1830s women were assuming more public roles in the fight against slavery, often encouraged by men like Garrison. In 1836 Garrison hired Angelina and Sarah Grimké as lecturers for the AASS. As members of a prominent slaveholding South Carolina family, the sisters were powerful spokesperson for the antislavery cause. They became favored speakers on the antislavery lecture circuit, attracting mixed-sex audiences. Their popularity shocked the general northern public. In 1837, the Congregational clergy issued a public rebuke, declaring that when women like the Grimké sisters assumed the public role of men, they risked shame and dishonor. The Grimké sisters, who believed they were answering God’s call to speak out against slavery, refused to stop lecturing. The clerical denunciations brought the “woman question” into sharper relief as other women joined the Grimké sisters in stepping beyond the boundaries of conventional female behavior in abolitionism.[11]

The abolitionist movement, along with the temperance movement, gave women a chance to be publicly involved in the reform of society. More radical reformers like the Grimké sisters, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton soon began agitating for their rights. These women and their supporters, including William Lloyd Garrison, argued that men and women were created equal and should be treated as equals under the law. Like abolitionism the women’s rights movement was radical. Equal rights for women carried serious implications for black civil rights if slavery were abolished. If women and blacks were granted full civil rights, opponents predicted chaos.

In May 1840 American abolitionists split over the question of strategies and tactics. Garrison and his supporters retained control of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison and the AASS maintained a broad reform platform, including women’s rights. The AASS recruited all abolitionists to the cause regardless of religious, social, and political views, requiring only a commitment to the abolition of slavery. Typically, members of the AASS included supporters of women’s rights and nonresistance. Abolitionism, women’s rights, and nonresistance were part of a larger emphasis on “moral suasion.” Slavery had so corrupted American society that emancipation would require a thorough, radical change in cultural values. Moreover, slavery had corrupted political and religious institutions, thus reformers must “come out” of such organizations and reform society from outside established institutions.[12]

Conservative members of the AASS, led by brothers Lewis and Arthur Tappan, formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFASS) after the brothers and three hundred supporters left the AASS. The Tappans and their supporters claimed other reform movements threatened the antislavery cause, which had to remain orthodox and compatible with traditional cultural norms such as the proper role of women in society. Causes such as women’s rights, if linked to abolitionism, could alienate the general northern public. The AFASS also emphasized political action. Members of the AFASS established the Liberty Party and nominated James G. Birney as its presidential candidate in 1840 and again in 1844.

These divisions among American abolitionists gained an international hearing at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in June 1840. Organized by members of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, antislavery associations were invited to send delegates to the convention to report on slavery, the slave trade, and the abolitionist movement throughout the world. The British organizers made it clear that only male delegates would be seated. Not surprisingly, the AASS selected a pro-women’s rights delegation including Lucretia Mott and Wendell Phillips as well as Garrison. When Garrison arrived in London, after being delayed by the AASS meeting, he found that the British abolitionists had refused to seat the AASS’s female delegates. In protest Garrison sat in the balcony with the ladies rather than enter the convention and be seated with the other delegates. When British abolitionists held the second World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1843, American abolitionists were represented by Lewis Tappan and the members of the AFASS. Garrison and his supporters were not invited. The AFASS was short-lived, however. The society stopped holding regular meetings in 1855. In contrast, the AASS continued to operate through the Civil War.

In the 1850s the organized abolitionist movement was eclipsed by the growing political crisis in the United States. In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which required all citizens to aid in the recovery of fugitive slaves or face prosecution. The act also denied fugitive slaves the right to a jury trial. As a result, thousands of blacks, regardless of status, fled north to Canada. Others remained in the United States often to their peril. In 1854 Boston abolitionists challenged the law, protesting the arrest of fugitive slave Anthony Burns. Boston was placed under martial law until Burns was placed aboard a ship bound for Virginia. The trial of Burns triggered a wave of opposition throughout the North. In protest William Lloyd Garrison burned a copy of the Fugitive Slave Act and a copy of the United States Constitution.

Garrison’s bonfire, however, was just one of many events that contributed to the increase of sectionalism in the 1850s. In 1852 abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe’s novel was the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century, generating a world-wide commercial industry in parodies, music, plays, and memorabilia. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, allowing settlers in the new territories to determine by popular vote whether to allow slavery. In a series of bloody skirmishes between pro- and anti-slavery settlers, “Bleeding Kansas” captured headlines across the country. Abolitionist John Brown and his sons gained notoriety for the murder of five pro-slavery farmers in Pottawatomie, Kansas. That battle was prelude to Brown’s attempted takeover of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859. In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled against the slave Dred Scott who had sued for his freedom, claiming that he should be freed because he had lived with his master in states where slavery was illegal. According to the court’s ruling, as a black man Scott was not a citizen of the United States and therefore could not bring suit in federal court. On the eve of the Civil War, debates about slavery engulfed every aspect of American life.[13]

The coming of war in 1861 re-energized the American abolitionist movement. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, men and women organized into associations and societies, believing collective action to be the most effective response to slavery and the slave trade. Yet even uniting for a single cause, the abolition of slavery, abolitionists often could not overcome differences in strategies and tactics. Still abolitionists demonstrated incredible resilience. For abolitionists, the coming of the Civil War was the culmination of a decades-long struggle for the slave’s freedom. Adoption of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment two years later assured abolitionists that their struggle, and the slave’s fight, had truly reached a successful conclusion.

- [1] The Great Awakening began in the late 1730s with a series of revivals led by George Whitefield. The religious fervor of the Great Awakening peaked in Virginia in the 1760s when the political crisis with Britain overshadowed religious revivalism.

- [2] John Woolman, “Some Consideration on the Keeping of Negroes, Recommended to the Professors of Christianity of Every Denomination, 1754” in The Journal and Major Essays of John Woolman, Phillips P. Moulton, ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 200-4; Disownment denied “the Quakerism of the delinquent.” Disownment did not bar the offender from attending the Monthly and Quarterly Meetings, which were open to the public. It did, however, prohibit the individual from calling themselves a Quaker, attending the Meeting for Worship, or receiving Meeting funds. See Pink Dandelion, An Introduction to Quakerism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 71-3.

- [3] David Walker, Peter P. Hinks, ed., David Walker's Appeal: To the Coloured Citizens of the World (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000).

- [4] All 103 issues of Freedom’s Journal can be viewed on line at the website of the Wisconsin Historical Society at http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/libraryarchives/aanp/freedom/ .

- [5] Bryan Edwards, Historical Survey of the French Colony in the Island of St. Domingo (London: John Stockdale, 1797).

- [6] Genius of Universal Emancipation was an abolitionist newspaper published in Baltimore MD by Benjamin Lundy from 1821-1839.

- [7] The Second Great Awakening refers to a series of religious revivals that swept through the New England area in the 1820s and 1830s. Itinerant preacher Charles Grandison Finney achieved his greatest success in upstate New York in the early 1830s.

- [8] Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate Not Gradual Abolition (Philadelphia: Philadelphia A.S. Society, Merridew and Dunn Printers, 1837).

- [9] The Liberator was a weekly abolitionist newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison from 1831-1865.

- [10] The House of Representatives used the “gag rule” from 1836-1844. The “gag rule” automatically tabled any antislavery petition, preventing any debate about slavery. In this same period, John C. Calhoun attempted to introduce a “gag rule” in the Senate. Calhoun’s measure was rejected, but the Senate did adopt a proposal that denied each antislavery petition as it arrived, achieving a similar prohibition on the discussion of slavery.

- [11] In the antebellum period, the distinction between the female-led home and the male-dominated workplace influenced the development of new ideas about gender and society that historians commonly refer to as the “ideology of separate spheres.” This ideology assumed that men earned enough to support their non-laboring wives and children at home. Thus men were linked to the public sphere of economic and political activity while women occupied the private space of the home and family. The “ideology of separate spheres” was more proscriptive than descriptive since many families required the economic contributions of all members of the household.

- [12] Nonresistance originated in Quaker faith in practical Christianity, taking literally Jesus’ command to resist not evil but turn the other cheek. Nonresistance should not be confused with pacifism. Rather nonresistance emphasized the importance of truth and love as weapons in the cause of justice. Some non-resistants, including William Lloyd Garrison, took nonresistance to its logical conclusion, refusing obedience to a government that maintained slavery through the use of violence.

- [13] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852).

If you can read only one book:

Stewart, James Brewer. Holy Warriors: American Abolitionists and American Slavery. New York: Hill and Wang, 1997.

Books:

Blackett, R.J.M. Building an Antislavery Wall: Black Americans in the Atlantic Abolitionist Movement, 1830-1860. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983.

Brown, Christopher Leslie. Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Burin, Eric. Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Faulkner, Carol. Lucretia Mott’s Heresy: Abolition and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Fladeland, Betty. Men & Brothers: Anglo-American Antislavery Cooperation. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Women and the Work of Benevolence: Morality, Politics, and Class in the Nineteenth-Century United States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Hansen, Debra Gold. Strained Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993.

Hersh, Blanche Glassman. The Slavery of Sex: Feminists-Abolitionists in America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978.

Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

Holcomb, Julie L. Moral Commerce: The Transatlantic Boycott of Slave Labor, 1757-1865. Ithaca,: Cornell University Press, forthcoming.

Jackson, Maurice. Let This Voice Be Heard: Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Kraditor, Alison. Means and Ends in American Abolitionism: Garrison and His Critics on Strategy and Tactics, 1834-1850. New York: Random House, 1967.

Laurie, Bruce. Beyond Garrison: Antislavery and Social Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Lutz, Alma. Crusade for Freedom: Women of the Antislavery Movement. Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

Melder, Keith E. Beginnings of Sisterhood: The American Woman’s Rights Movement, 1800-1850. New York: Schocken Books, 1977.

Newman, Richard S. The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Plank, Geoffrey. John Woolman’s Path to the Peaceable Kingdom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Quarles, Benjamin. Black Abolitionists. New York, Oxford University Press, 1969.

Reynolds, David. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Vintage, 2006.

Richards, Leonard L. Gentlemen of Property and Standing: Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America. New York, Oxford University Press, 1970.

Robertson, Stacey. Hearts Beating for Liberty: Women Abolitionists in the Old Northwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Rugemer, Edward Bartlett. The Problem of Emancipation: The Caribbean Roots of the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

Salerno, Beth A. Sister Societies: Women’s Antislavery Organizations in Antebellum America. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Yee, Shirley J. Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism, 1828-1860. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

Yellin, Jean Fagan and John C. Van Horne, eds. The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection at Cornell University. The Cornell University Library owns one of the richest collections of anti-slavery and Civil War materials in the world, thanks in large part to Cornell's first President, Andrew Dickson White, who developed an early interest in both fostering,

Quakers and Slavery is a project at Bryn Mawr College. The goal of this project is to increase public accessibility to rare historical materials formerly available only on-site at the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College and the Quaker & Special Collections at Haverford College.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.