The Battle of Ball's Bluff

by James A. Morgan

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff, October 21, 1861, was a simple accident that resulted from a faulty report provided by an inexperienced officer who led a reconnaissance patrol and thought he saw something that was not there. Confederate Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans had 3,000 men near Leesburg Virginia when Federal forces began building up at Langley, 25 miles east of Leesburg, numbering about 24,000 men. The federal forces advanced towards Evans’ position. On the night of October 20 a small union patrol crossed the Potomac River at Balls Bluff led by Captain Chase Philbrick who reported seeing an unguarded Confederate Camp, mistaking trees for tents and failing to take steps to verify that a camp was indeed there. Union Brigadier General Charles Stone decided to mount a raid on the camp. About 400 Union troops of the 15th and 20th Massachusetts Regiments were ferried across the river in three small boats on the night of October 20-21, about 35 at a time. At 6:00 a.m. as soon as it was light, the Union force advanced to attack the “camp”. The Union colonel in charge of the raiding force, Charles Devens, discovered the error, sent an aide to report it to General Stone (on the other side of the river and three miles away) and waited for new orders. General Stone ordered the rest of the 15th Massachusetts to cross the river to support Devens and ordered Devens to advance towards Leesburg on an expanded reconnaissance mission. While these orders were being transmitted by aides riding between the general and the raiding party, Confederate forces had advanced and engaged Devens. Colonel Edward Baker, a U.S. Senator and one of Lincoln’s closest friends, had been ordered to advance his 1st California Brigade towards Ball’s Bluff and take command of all the Union troops in the area. Baker began sending troops across the river, remaining on the Maryland side looking for more boats. Not only did he not go to the battlefield but he put no one in overall command there. Meanwhile fighting continued sporadically between the two, roughly evenly matched forces on the Virginia side of the river. By late afternoon Baker had crossed the river and Devens had fallen back into a defensive position above the bluff. Here the Confederates assaulted the Union troops repeatedly. Sometime between 4:30 and 5:00 p.m. Colonel Baker was killed. Shortly before dusk the 17th Mississippi with 600-700 fresh troops arrived on the battlefield, advanced and broke the Federal line. Panic-stricken Federals rushed down the bluff to the river. Many were shot there or drowned trying to swim the river. More than half the union force became casualties, 223 killed, 226 wounded and 553 captured out of 1,700. The Confederates suffered 36 killed, 264 wounded and 3 captured. Though small by later standards the Battle of Ball’s Bluff mattered in 1861. While Colonel Baker was primarily responsible for the loss, General Stone saw his career ruined. He was arrested and held for six months then released without charge, apology or explanation. Political pressure arising from the Union defeat at Ball’s Bluff resulted in the creation of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

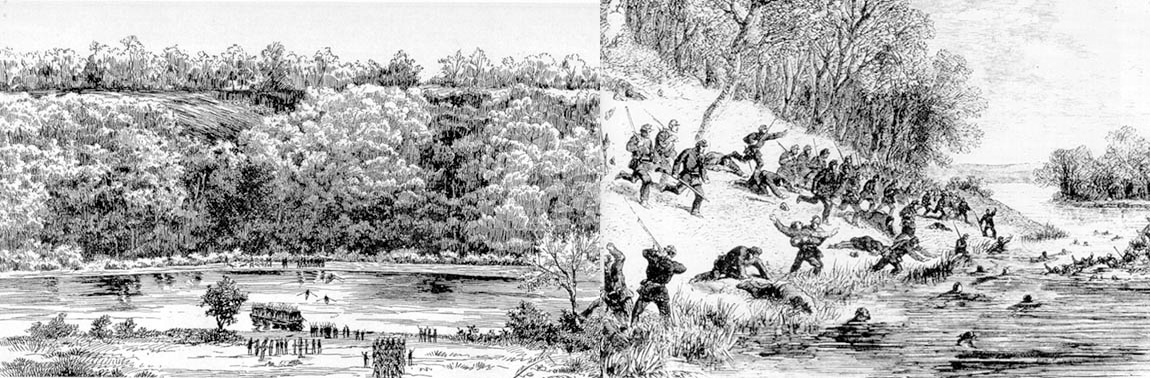

Cliff at Ball's Bluff Opposite Harrison's Island/Retreat of the Federalists After the Fight at Ball's Bluff-Illustrated London News November 23, 1861-page 514.

Images Courtesy of: Massachusetts Historical Society/Library of Congress

The telling of the Ball’s Bluff tale over the years has tended to treat that little battle as a pre-planned, but bungled, attempt by the Federals to take Leesburg. Such an attempt in fact had been feared by the Confederate commander, Colonel Nathan George “Shanks” Evans and, given the deployment of the various Union forces in the area on the morning of October 21, 1861, it surely would have seemed that way once the fighting began. Nonetheless, Ball’s Bluff had nothing to do with taking Leesburg. It was a simple accident that resulted from a faulty report provided by an inexperienced officer who led a reconnaissance patrol and thought he saw something that was not there.

For about three weeks prior to the battle, Evans had been carefully watching the growing Union forces in the area, fearing that they might attempt to cut him off. His concerns began at the beginning of October when Brigadier General Charles Pomeroy Stone’s Corps of Observation was reinforced by Colonel (and U. S. Senator) Edward Dickinson Baker’s very large California Brigade. Almost overnight it seemed, Stone’s strength nearly doubled, increasing from roughly 7,000 men to about 12,000.[1]

Then, on October 9-10, Union Brigadier General George Archibald McCall crossed his own 12,000-man Pennsylvania Reserves division into Virginia and established a camp at Langley, only 25 miles east of Leesburg. Suddenly, Evans had to deal with the fact that there were some 24,000 Yankees closer to him than he was to any other part of the Confederate army. With his own force numbering fewer than 3,000 men, this got his attention.

Colonel Evans reasonably interpreted these movements as indicating a possible Union advance on Leesburg. The town was strategically significant as a regional transportation hub and because whoever controlled the fords and ferry sites in the vicinity controlled the invasion routes leading both north and south. Evans was legitimately concerned that his small, trip-wire brigade might prove too tempting a target to the nearby enemy.

Following some skirmishing upriver at Harper’s Ferry, which may well have looked to him as a prelude to an attempted envelopment, Evans, without the permission of his superiors, abandoned Leesburg on the night of October 16. He marched his men southward and established a new defensive line behind Goose Creek some eight miles from town near Oatlands Plantation.

General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was displeased when he heard of the move and sent Evans a somewhat sarcastic message saying that he “wishes to be informed of the reasons that influenced you to take up your present position, as you omit to inform him.”[2] Evans took the hint and, by late on October 19, his brigade had returned to its Leesburg camps.

Not surprisingly, the Confederate departure had been observed by the Federals. Major General George Brinton McClellan, the overall Union army commander, suspected a trap, thinking that Evans might be attempting to draw some of his forces forward in order to cut off and destroy them. He ordered General McCall to take his division on a reconnaissance-in-force as far as Dranesville, about halfway between Langley and Leesburg, then to cautiously probe toward the latter town. McCall advanced westward along the Georgetown Pike but brought only one of his three brigades, that commanded by Brigadier General John Fulton Reynolds, as far as Dranesville. By coincidence, he arrived there on October 19, the very day of Evans’ return to Leesburg.

Confused by the return of the Confederates, McClellan ordered McCall to return to Langley the next morning but, at McCall’s request, allowed him an extra 24 hours to complete some maps of the road network in the area. He also was to continue his probes toward Leesburg.

On October 20, while McCall was conducting his missions, Evans had deployed much of his force along another portion of Goose Creek four miles east of Leesburg and was waiting for him. With McCall’s continued activity in mind, McClellan ordered General Stone to conduct a “slight demonstration” hoping that Stone’s and McCall’s movements together would result in Evans once again withdrawing from Leesburg.[3]

By the evening of October 20, Stone’s slight demonstration was over and the regiments that he had used to put on a show of crossing at Edwards Ferry (three miles downriver from Ball’s Bluff) were on their way back to their camps for the night. He needed to know what effect his demonstration might have had, however, so he ordered Colonel Charles Devens Jr., commanding the 15th Massachusetts, to send a patrol across the river at Ball’s Bluff.[4] Devens gave the assignment to Captain Chase Philbrick and his Company H partly because this company was already on Harrison’s Island which bisected the Potomac at that point and partly because Philbrick had led a similar patrol on the evening of October 18 which had familiarized him with the area. On October 18, of course, the Confederates were not there.

Around dusk, Philbrick and perhaps 20 volunteers used two small skiffs to row as quietly as they could from the island to the floodplain at Ball’s Bluff. This was somewhat tricky to accomplish in the dark but Philbrick made it without mishap. His patrol then moved downriver along the floodplain, then up the bluff itself on a winding path that came out just behind the current national cemetery, and advanced inland along a small road, now graded and graveled, later described as “an indistinct cart path some ten or twelve feet in width.”[5] They crossed a large clearing (eventually the focal point of the battle) and passed through some woods to the open fields that now are the site of the Potomac Crossing subdivision.[6]

Lieutenant Church Howe described the patrol: “We proceeded … three quarters of a mile or a mile from the edge of the river. We saw what we supposed to be an encampment. (There was) a row of maple trees; and there was a light on the opposite hill which shone through the trees and gave it the appearance of the camp. We were very well satisfied it was a camp.”[7]

Captain Philbrick mistook the trees for tents. Without verifying what he thought he was seeing, however, he took his patrol back across the river and reported the presence of an unguarded camp. General Stone sensed what today would be called a target of opportunity, though he called it “a very nice little military chance,” and ordered a raid.[8] From this decision, based solely on Captain Philbrick’s faulty report, came the battle of Ball’s Bluff. The raid on the camp has sometimes been confused by historians with the “slight demonstration” of October 20, though the two were discrete events only indirectly connected. The demonstration at Edwards Ferry in fact was ending as the Philbrick patrol at Ball’s Bluff was getting underway. The raid was organized after the patrol’s return and only because of the mistaken report. Preparations continued into the early hours of October 21.

The raid had only the limited purpose of attacking the supposed camp. But it appeared to the Confederates to be a more ambitious movement because, in addition to the crossing at Ball’s Bluff, a small, diversionary crossing of cavalry was made downriver at Edwards Ferry. With McCall’s division poised in and around nearby Dranesville — Evans being unaware that it was preparing to leave — and Federal infantry and cavalry crossing the river at two points near Leesburg, the situation on the morning of October 21 must have appeared to Colonel Evans as the envelopment he had suspected and feared enough to have abandoned the town a few days earlier. Now he believed that he would have to fight what, for his small brigade, would be a desperate battle against overwhelming numbers of the enemy. This is not what happened but one can readily understand why Evans believed that it would.

The diversion at Edwards Ferry was intended primarily to give cover to Colonel Devens’ raiding party. General Stone ordered Major John Mix to cross the river with 30 of his 3rd New York Cavalry troopers, advance toward Leesburg, and attract Confederate attention to himself so that the raiding party upriver could conduct its raid and get back safely. Mix was also ordered to scout the roads between the ferry and the Alexandria-Winchester Turnpike, the eastern approach to Leesburg on which McCall would come should General McClellan order him to advance. Having accomplished these tasks, Mix was to withdraw to Maryland.[9]

McCall’s instructions from General McClellan, however, would take him away from the fighting. He was under orders to complete his probes and his map-making and return to Langley on the morning of October 21 (an important fact of which General Stone was unaware as General McClellan had neglected to inform him).

None of the three Federal forces in the area that morning were there to attack the town. The assumption that they were has gained credence through repetition over the years and Ball’s Bluff thus has consistently been misinterpreted as having resulted from Stone’s implementation of a pre-existing plan. The Federals all had limited missions and the only documented Union plan to take Leesburg was written by Stone in late January, 1862, three months after the Battle of Ball’s Bluff.

Colonel Devens carefully shuttled his 300-man raiding party across the river in three small boats carrying approximately 35 men per trip. In addition, another 102 men from the 20th Massachusetts followed. They would deploy on the bluff to cover the rear of Devens’ force and then its withdrawal following the raid.

Getting over 400 men across the river in three small boats, quietly and at night, was especially difficult because heavy rains during the previous three weeks had caused the Potomac to rise well above its normal level and the current in the narrow channel between Harrison’s Island and Virginia was dangerously swift. The crossing took most of the night but was successfully accomplished without incident. Around 6:00 a.m. as soon as it was light enough to see, Colonel Devens advanced to attack the “camp.”[10]

He soon discovered the patrol’s error. Had he then returned to the island, as he might reasonably have done with the raiding party having nothing to raid, there would have been no battle. But the morning was quiet and his force, as far as he could tell, remained undiscovered. So he used his discretionary authority as commander on the field and decided to remain.

Deploying his men along the tree line which currently marks the boundary between the Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park and the Potomac Crossing subdivision, Devens sent Lieutenant Howe to report to General Stone and request further instructions. Howe returned to the bluff, descended it, crossed the Virginia channel of the river to Harrison’s Island, then crossed the island and the wider Maryland channel of the river, then got onto the C&O Canal towpath and rode the three miles downriver to Edwards Ferry. He reported to Stone about 8:00 a.m. Reacting to Howe’s new information, Stone ordered the remainder of the 15th Massachusetts to join Devens with instructions that Devens was to advance this larger force toward Leesburg in what had now become an expanded reconnaissance mission. Howe went ahead of these reinforcements and brought Colonel Devens the new orders.

Unknown to General Stone, however, Devens was engaging the enemy even as Lieutenant Howe was making his initial report that everything was quiet. His new orders thus were already outdated as he was issuing them to Howe. Pickets from Company K, 17th Mississippi briefly had engaged a small patrol from the 20th Massachusetts near Smart’s Mill, a mile or so upriver from Ball’s Bluff, earlier in the morning and then sent word to Colonel Evans that Union troops were across the river at Ball’s Bluff. Curiously, no one from the 20th Massachusetts went forward to inform Colonel Devens of the contact so we can only imagine his surprise when his pickets reported Confederate troops moving toward his position.

When Lieutenant Howe returned to the Virginia side of the river and brought the new orders to his regimental commander, Colonel Devens immediately sent him back to General Stone once again with the information that he already had engaged the enemy. The time lag necessary to get information across the river was becoming problematic for the Union force.

Captain William Duff, who would have been an 1862 graduate of Ole Miss had the war not intervened, had 45 men in his Magnolia Guard. On hearing from the pickets, Duff mustered his company and moved southward in order to get between the Yankees and Leesburg. He encountered Devens’ men not far from the home of the widowed Mrs. Margaret Jackson near where the non-existent camp was supposed to have been. Mrs. Jackson’s home, though greatly altered, still stands today.

In the fields west of her home, Duff’s Mississippians engaged a portion of Devens’ Massachusetts men. Devens had 300 men with him but, not sure how many Confederates there were, he sent only Captain Philbrick’s 65-man Company H forward to meet this unexpected enemy and held the rest in reserve. This initial skirmish lasted some 15-20 minutes with the southerners getting the best of it. They killed one, wounded nine, and captured three of the Federals while having only three wounded themselves. Both companies withdrew and there began a three-hour lull as each side watched the other and the events of the day began to unfold.

Shortly after Howe left General Stone with the instructions to turn the raid back into a reconnaissance, Colonel Edward Baker arrived at Edwards Ferry to find out what was going on. He had played no part in the events up to that point except that Stone had ordered him, late on October 20, to bring his brigade to Conrad’s Ferry, just above Harrison’s Island, in case it might be needed. This was part of Stone’s quickly devised plan to raid the supposed Confederate camp. Baker had put his men in motion toward Conrad’s early on the morning of October 21. By dawn, his 1st California was in place.

Based on Lieutenant Howe’s outdated information, Stone ordered Baker to take command of all the troops in the area that faced Ball’s Bluff, then to evaluate the situation and either cross additional troops or recall those already in Virginia as he saw fit. It is important to remember that neither Stone nor Baker knew that fighting already had begun. Both were thinking only of an expanded reconnaissance toward Leesburg.

While on his way upriver shortly before 10:00 a.m., Baker met Lieutenant Howe returning to Edwards Ferry with the new information about the skirmish. He told Howe that he was “going over immediately, with my whole force, to take command.”[11] This is what Howe reported to General Stone but, in fact, Baker did not cross the river. Instead, he ordered all the troops in the area to begin crossing while he remained on the Maryland side and spent most of the next four hours looking for more boats, a job which he should have turned over to a subordinate while he went to the battlefield to take command. Not only did he not go to the battlefield himself, but he sent no orders and he put no one in overall command on the Virginia side. With few boats available, most of the Union troops spent the day waiting in line for transportation as the lead units crossed a few men at a time, first to the island then to the Virginia shore.

While all of this was taking place, there were two more skirmishes in the vicinity of the Jackson house. One occurred about 11:30 a.m. between the now 650-strong 15th Massachusetts and a mixed force of detached Mississippi infantry and Virginia cavalry companies totaling about the same number and now commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Walter Jenifer, a Marylander and former lieutenant and Indian fighter with the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. As it happened, the opposing forces at Ball’s Bluff were fairly evenly matched throughout the day though each side reported being heavily outnumbered by the other.

A third skirmish took place about 1:00 p.m. after the 8th Virginia (minus one company) arrived with just under 400 men. Larger, but also indecisive, it was followed by another lull during which, around 2:00 p.m., Colonel Devens withdrew to the bluff, where he knew that he would have some help.

When Devens arrived at the bluff, he found Colonel Baker who finally had decided to cross the river himself. Baker approved of Devens’ withdrawal and ordered him to deploy on the right, perpendicular to the existing Federal line. This created a defensive position that would have looked from the bluff like a backwards capital “L.” The left wing faced west (the men’s backs were to the bluff above the southward-flowing river) while Devens’ men in the right wing faced south. Together they covered the road and the open field with a potentially deadly crossfire.

About 3:00 p.m., Baker sent Companies A and D of the 1st California (later re-designated the 71st Pennsylvania) up the slope on his left front between today’s cemetery and parking lot in order to gauge the enemy’s strength. This resulted in a clash with a portion of the 8th Virginia near the site of today’s parking lot. From then on, there was almost continuous fighting until dark.

Both sides suffered heavily in this brief but intense hand-to-hand encounter. The Californians lost two-thirds of the approximately 180 men involved then fell back to the main Union line near the bluff. The rightward-most companies of the Virginians, apparently believing they had been flanked and misunderstanding an order by Colonel Eppa Hunton to withdraw and regroup, simply broke and ran. Colonel Hunton deserves great credit for preventing the spread of what might have become a disastrous panic but between one-quarter and one-third of his men fled as far as Leesburg. Hunton moved the rest of the 8th to a large field near the Jackson house and spent the next one and one-half to two hours reorganizing and getting it back into the fight. Most of the men who had fled did return eventually and the unit was involved in one more charge later in the day.[12]

When Hunton withdrew, the 18th Mississippi, led by Colonel Erasmus Burt, took his place in the line and soon advanced across the field, marching right between the two wings of the Federal position. Colonel Burt’s tactical error here resulted from his not being able to see the Federal right as those men were under the cover of woods and sloping ground while the left was in the open. Burt marched directly into what Confederate soldier Elijah White later called “the best directed & most destructive single volley I saw during the war.”[13] Colonel Burt became one of the casualties. Shot through the hip and stomach, he was taken into Leesburg where he died on October 26 in a private home called Harrison Hall. Erasmus Burt was the highest ranking Confederate to be killed at Ball’s Bluff.

As a curious historical aside, it can be noted that Harrison Hall, still standing and today known as Glenfiddich, was the house in which Confederate Generals Lee, Longstreet, Jackson, and Stuart met on September 5, 1862 and planned what became the Antietam campaign.

Following their repulse, the Mississippians quickly withdrew and split into two battalions. One moved to flank the Federals on the left and the other to do the same on the right. This created a wide gap in the Confederate line, roughly around today’s parking lot, which Colonel Milton Cogswell of the 42nd New York noticed and urged Colonel Baker to exploit by pushing his troops forward. Baker refused, however, and remained on the defensive. The gap eventually was filled by the 17th Mississippi.

From this point, the fighting was a confused swirl of individual company or battalion actions. Heavy skirmishing persisted on the Confederate left all afternoon, but the heaviest fighting was on their right. The Mississippians who had moved into the ravines on the right assaulted the Federals at least five times during the afternoon and were repulsed each time. It most likely was during the last of those assaults between 4:30 and 5:00 p.m. that Colonel Baker was killed, though there is no historically definitive account of his death. Baker, one of President Lincoln’s closest friends, is the only U. S. senator ever to die in combat.

With Baker’s death, command of the Union troops fell to Colonel Cogswell. Colonel Devens and Colonel William Raymond Lee of the 20th Massachusetts both urged a retreat, but Cogswell wanted first to attempt to break out of the constricted position by advancing, as he earlier had urged Baker to do, so as to give his force room to maneuver and better use its artillery.

Cogswell’s breakout attempt, however, was a desperation move conducted by worn out men short on water and ammunition. It came too late and quickly collapsed, at which point Cogswell ordered his men to simply hold off the Confederates for as long as they could so that he could evacuate as many of the wounded as possible. Then, shortly before dusk, the 17th Mississippi, 600-700 fresh troops with full cartridge boxes, arrived on the field and effectively sealed the fate of the Federals. Supported by the 18th and possibly by a company of the 13th Mississippi and some dismounted Virginia cavalrymen, the 17th advanced and broke the Union line.

The panic-stricken Federals rushed down the steep slope at the southern end of Ball’s Bluff as far as the river. Many of them drowned or were shot as they attempted to swim to Harrison’s Island. Others took cover at the base of the bluff and either swam the river after dark or later surrendered. More than half of the Union force became casualties: 223 killed, 226 wounded, and 553 prisoners out of a total force of 1,700. The Official Records state that 49 Union soldiers were killed in the battle, but that figure, often cited in secondary accounts because of its appearance in the Official Records, is wrong. Regimental returns, medical records, and the many reports of bodies washing ashore along the Potomac in the days following the battle, provide the higher, more accurate numbers. The Confederates, who also put about 1,700 men into the fight, suffered 36 killed, 264 wounded, and three captured.[14]

The primary responsibility for the Federal debacle must be laid at Baker’s feet. As commander on the field, he made too many poor decisions with regard to the crossing and the deployment of his men. The Confederate command structure, however, had its own problems as the ranking officer on the field changed several times during the day. Captain Duff was succeeded by Lieutenant Colonel Walter Hanson Jenifer, who was succeeded by Colonel Hunton until the 8th Virginia fell into disarray. Colonel Erasmus Burt of the 18th Mississippi briefly commanded until he was wounded and taken from the field, leaving Jenifer again as the senior officer for a time. On Hunton’s return, he commanded the Virginians and the detached Mississippi companies on the left. Colonel Winfield Scott Featherston of the 17th Mississippi arrived and commanded his regiment and the other Confederates on the right.

Having succeeded in getting the 8th Virginia back together, Colonel Hunton led one more charge on the left and overran two Federal mountain howitzers. He then withdrew his regiment once again and thus was not involved in the climactic assault led by Colonel Featherston which finally drove the Union troops into the river. Featherston was in overall command of the Confederates on the field at the end of the day.

Ball’s Bluff was, by later standards, a very minor affair, soon overshadowed by larger, bloodier battles. In 1866, General Stone described it as being “about equal to an unnoticed morning’s skirmish on the lines before Petersburg at a later period of the war.”[15] In late 1861, however, it mattered.

Despite being publicly exonerated by General McClellan, General Stone saw his career ruined as a result of the aftermath of this battle. He was arrested in February, 1862 and held for six months with no charges ever being filed against him. That August, he was peremptorily released without apology or explanation.[16]

Six weeks after the battle, political pressures increased when the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was organized and Congress became deeply involved in all war-related activities from then on. On the military side, it was the third consecutive Confederate victory of the year (First Manassas, Wilson’s Creek, and Ball’s Bluff) and was celebrated by southerners as a sign of their soon-to-be-achieved independence. Unionists, however, cursed the name and would not soon forget “the red memory of Ball’s Bluff.”[17]

- [1] Adjutant General Lorenzo Williams to Brigadier General Charles Stone, Oct. 17, 1861. Corps of Observation Records, Box 1, National Archives, Washington, DC.

- [2] Beauregard to Evans, United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 5, p. 347 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 5, 347).

- [3] O.R., I, 5, 34.

- [4] Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War in Three Parts: Part II Bull Run- Ball’s Bluff, H.R. Rep. No. 37-, at 403 (1863) (Testimony of Colonel Charles Devens) (hereafter cited as JCCW).

- [5] George H. Gordon, “Bloody Ball’s Bluff,” National Tribune, July 26, 1883.

- [6] The reader should know that this clearing, roughly 12 acres in extent, became thickly overgrown in the years after the war. A battlefield restoration project was initiated in 2009 by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority. With the labor of NVRPA personnel and volunteers, approximately nine of the 12 acres have been cleared and restored to their wartime appearance as of the date of this article. As time permits, the remainder of the 1861 field will be restored.

- [7] JCCW, 375 (Testimony of Lt. Church Howe).

- [8], JCCW, 277 (Testimony of Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone).

- [9] O.R., I, 5, 294.

- [10] JCCW, 405 (Devens testimony).

- [11] JCCW, 376 (Howe testimony).

- [12] Elijah V. White, History of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff: Fought on the 21st of October, 1861,1904 ed. reprint (Manassas, VA: Manassas Museum, 1983),10.

- [13] Elijah V. White, Ball’s Bluff Address, 1887, Miscellany Collection, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg VA.

- [14] O.R., I, 5, 308; Joseph K. Barnes, Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865) (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1870), 7:38.

- [15] Charles P. Stone letter to Benson Lossing, November 5, 1866, James S. Schoff Civil War Collection, The Clements Library, University of Michigan.

- [16] James A. Morgan III, A Little Short of Boats: the Battles of Ball’s Bluff and Edwards Ferry, October 21-22, 1861 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2011) 198-204,(for a more complete discussion of the fate of General Stone).

- [17] L.N. Chapin, A Brief History of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment N.Y.S.V. (New York: 1903), 29.

If you can read only one book:

Morgan III, James A. A Little Short of Boats: the Battles of Ball’s Bluff and Edwards Ferry, October 21-22, 1861 El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2011.

Books:

Ballard, Ted. Battle of Ball’s Bluff: Staff Ride Guide. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2001.

United States War Department. War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 5 (Material on Ball’s Bluff).

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War in Three Parts: Part II Bull Run- Ball’s Bluff, H.R. Rep. No. 37-. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1863 (Material on Ball’s Bluff).

Organizations:

Friends of Ball’s Bluff Battlefield

This is a fund-raising and support group affiliated with Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority which owns the Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park. Jim Morgan is chairman of this group and is the contact for questions or further information You can join their Facebook group

Web Resources:

Civil War Trust Ball’s Bluff page.

Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park.

Other Sources:

Thomas Balch Library

History and genealogy library in Leesburg, VA; extensive collection of Ball’s Bluff materials. 208 West Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 (703) 737-7195.