The Battle of Perryville and Bragg's Kentucky Campaign

by Kenneth W. Noe

After the Battle of Perryville in October 1862 the Confederate Army the Mississippi retreated from Kentucky.

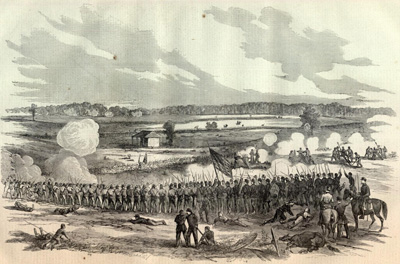

The Battle of Perryville, fought on October 8, 1862, was the largest and most significant Civil War battle fought in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Although tactically a Confederate victory, General Braxton Bragg's subsequent retreat from the state effectively ended any real hopes of extending the boundaries of the Confederacy north to the Ohio River. The men who fought at Perryville meanwhile remembered it as one of their hardest contests, a "soldiers' fight" shaped by a breakdown of command-and-control as well as vicious fighting in the midst of a searing drought.

After the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, Confederate forces retreated first to Corinth Mississippi, and then farther south to Tupelo. Angry that commander General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard chose that moment to leave the army in order to recuperate at a nearby resort, President Jefferson Davis fired him and replaced him with Bragg. The new commander of what was then styled the Confederate Army of the Mississippi struggled to rebuild his battered force while developing an operational plan. Bragg believed that he lacked the strength to regain Corinth. A more promising option presented itself when Major General Henry Halleck, commanding in Corinth, ordered Major General Don Carlos Buell's Federal Army of the Ohio to the east, across northern Alabama toward the vital railroad junction at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Confederate cavalry raids battered Buell's railroad supply line even as a developing drought undermined river transportation. The pace of Buell's dusty march slowed until the van ground to a halt in northeastern Alabama, leaving his forces strung out across the line of march.

Buell's flank offered a tempting target to Bragg. In the end, however, other concerns provoked a different response. From Chattanooga itself, Major General Edmund Kirby Smith bombarded Bragg with repeated requests for reinforcements, expecting Buell to overwhelm his small army any day. Meanwhile, influential politicians pushed Bragg to launch a campaign that would liberate both Tennessee and Kentucky from Union control. According to the raider Colonel John Hunt Morgan, Kentucky increasingly resented Union occupation and only awaited the appearance of a significant Confederate force before rising up against the Lincoln Administration. Thus on July 21, Bragg telegraphed Richmond that he was moving most of his army to Chattanooga, hoping to head off Buell before the Union force could reach the city. With the most direct route controlled by the enemy, Bragg's army moved south via railroad starting on July 23, took ferries across Mobile Bay, and then remounted railroad cars for a journey to Chattanooga via Atlanta. Encompassing 776 miles in all, Bragg's troops began arriving as early as July 27. It was one of the most remarkable troop movements of the war. In Chattanooga, Bragg and Kirby Smith agreed that after the latter had reduced the Federal garrison at Cumberland Gap, the two combined forces would defeat Buell somewhere in Middle Tennessee and then march north to Kentucky.

Hungry for praise, comparing himself to Moses and Hernando Cortes, Kirby Smith quickly reneged on the agreement. Bypassing Cumberland Gap, which he called too strong to seize, he instead marched his force north toward Kentucky. On August 30, his army, augmented by two brigades borrowed from Bragg, annihilated a Union force at Richmond. Kirby Smith seized Lexington soon thereafter. The sudden appearance of a Confederate army in the Kentucky bluegrass deeply alarmed the governors of the Midwest, all of whom quickly began raising new troops to defend their borders. New units hurried to Cincinnati and Louisville. Concerned that he might be driven from the state, Kirby Smith meanwhile called on Bragg to march north and join him.

Bragg in fact already had started moving north on August 26, determined to bypass the Federal garrison at Nashville and strike quickly for Kentucky. He took up a line of march that took him east of the city, moving at first toward Sparta, Tennessee. Meanwhile, Buell's army fell back as well. Indeed, alarmed by erroneous reports of a Confederate forward movement, Buell had started pulling out of Alabama days before Bragg actually marched. Deeply concerned about safeguarding his supply line, Buell initially fell back to Nashville, ignoring the advice of subordinates such as Major General George Henry Thomas that he instead stand and fight. Once in the Tennessee capital, Buell determined to march even farther north, to protect his supply base at Louisville. Thus the two contending armies raced north across central Kentucky on parallel paths in what many soldiers likened to a foot race. Both armies suffered from the heat, increasingly short rations, and a growing dearth of potable water.

On September 14, acting without orders from their commanders, Brigadier General James Ronald Chalmers of Bragg's army and Colonel John Sims Scott, commanding a detachment of Kirby Smith's cavalry, initiated an ill-advised attack on the entrenched Federal garrison at Munfordville, Kentucky. Worried that the repulse would undermine Confederate sentiments in the Bluegrass State, Bragg marched his entire force to Munfordville and compelled the garrison to surrender. The delay allowed Buell to draw near. Briefly Bragg considered making a stand against Buell there, but instead returned to the march. On September 22 Confederate forces halted at Bardstown, disappointing many of his men who had assumed they were hurrying to take Louisville. Buell's exhausted men began arriving in that city on September 25, angry that their commander had allowed Bragg to come so far north without a fight. Indicative of the soldiers' low morale, wild rumors circulated that the two generals actually were brothers-in-law who slept together nightly while making plans for another's day non-violent marching.

Over the next several days, confusion gripped both commanders. While resting and refitting his army, now augmented by the new recruits who had been defending the city, Buell reorganized his army into three corps, to be commanded by Major Generals Alexander McDowell McCook, Kentuckian Thomas Leonidas Crittenden, and trusted subordinate William "Bull" Nelson, formerly an officer in the U. S. Navy. George Thomas would serve as Buell’s second-in-command. This plan quickly went awry when a simmering feud led Brigadier General Jefferson Columbus Davis to shoot Nelson to death in the lobby of a local hotel. Buell replaced Nelson with another loyalist, Charles Champion Gilbert, an erstwhile captain who recently had been promoted to "acting major general." Gilbert's appointment angered officers under his command while his martinet ways embittered the rank-and-file. Meanwhile, angry at Buell's actions, the Lincoln Administration sent a telegram to Thomas ordering him to take command of the army. Citing Buell's preparations and planning, Thomas refused for the moment. Buell meanwhile drew up plans for offensive operations against Bragg, designed to drive him from the state.

Bragg also dealt with perplexity. Expecting Kirby Smith to join him in Bardstown, where the senior Bragg would assume command of the entire force, he was surprised to discover that instead the jealous officer not only had marched in the opposite direction, but had delayed dispatching requested supplies. Meanwhile few of the promised Kentuckians came forward to enlist. Bragg lurched between optimism and pessimism, attack and retreat, but finally determined to leave his army, ride to the state capital at Frankfort, and along with Kirby Smith formally install the commonwealth's Confederate governor, Richard Hawes. Bragg expected Hawes to extend Confederate conscription to the state. The army remained in Bardstown under the temporary command of Major General Leonidas Polk, a former Episcopalian bishop whom Bragg despised but could not dispense with due to Polk's long friendship with the Confederate President.

On October 1, Bragg arrived in Lexington and met with Kirby Smith. On the same day, Buell's projected movement began. Two divisions under the command of Brigadier General Joshua Woodrow Sill feinted toward Frankfort. The rest of the army took three separate routes toward Bardstown. Buell's plan had the desired effect of befuddling the Confederate high command. Mistaking Sill's column for Buell's entire force, an erroneous conclusion strengthened by reports from Kirby Smith's cavalry, Bragg ordered Polk to move north toward Frankfort and join forces with Kirby Smith's army. Confronted with growing pressure from the direction of Louisville, however, Polk instead retreated toward Danville. Bragg and Polk continued to work at cross purposes as the former bishop repeatedly ignored Bragg's orders to swing north and instead continued to retreat. Extant correspondence demonstrates that neither man had an accurate grasp of what actually was happening. Meanwhile, Bragg presided over the installation of Hawes on October 4, a ceremony cut short by the sounds of Sill's artillery followed by the Confederates' hasty abandonment of Frankfort.

On October 7, the Confederate Army of the Mississippi passed through the small town of Perryville. While the men took little notice of it, Bragg's staff had been aware of Perryville's importance for some time. The three roads that Buell's corps traversed-the Mackville Road, Springfield Pike, and Lebanon Road respectively from northwest to southwest-all converged in Perryville before again dividing to the east. Just as importantly in the extended drought was water. The town straddled the Chaplin River, which at least offered pools of water in its otherwise dry bed. The Chaplin continued meandering to the north for over two miles before it briefly turned southwest to create Walker's Bend, a thumb-shaped peninsula characterized by high bluffs. From the bend, Doctor's Creek branched off to the southwest, crossing the Mackville Road at the home of "Squire" Henry P. Bottom, a local magistrate. In additional to stagnant pools in the riverbeds and creek bed, local springs offered fresh water. Control of that water would become crucial in the hours ahead.

As the army passed through town, a series of communiqués passed between Bragg, Polk, and Major General William Joseph Hardee, who was with Polk. Bragg initially wanted the army to keep moving north toward Lexington, but by evening Hardee and Polk had convinced him that the Federal force on the Springfield Pike-Gilbert's III Corps as it turned out-was significant enough to offer a threat to the rear. All day Union and Confederate cavalry had clashed west of town on that route. Poorly using that cavalry for scouting, a hallmark of the entire campaign on both sides, Hardee and Polk seemed to think that they faced no more than a division or two, and reported no additional threats on the Mackville or Lebanon roads. Bragg gave them permission to deal with the pursuers before moving again north on the morrow toward a concentration with Kirby Smith. While Major General Jones Mitchell Withers' division kept moving, the rest of the army concentrated in Perryville along a north-south axis just east of the riverbed. A mile farther out the road, Brigadier General St. John Richardson Liddell's Arkansas Brigade took a position on Bottom Hill, named for Squire Bottom's cousin Henry. The 7th Arkansas moved west to the next eminence, Peters Hill, where it shielded both the remainder of the brigade and a freshwater spring. The entire area west of town, known as the Chaplin Hills, was marked by rolling terrain that limited visibility.

Out on the Springfield Pike, III Corps arrived in the vicinity of the town at dusk and began going into camp. Jaded by the march, the men were exhausted and angry. When Buell tried to chase foragers from a garden, one soldier frightened the general's horse, which threw Buell from the saddle. Injured, Buell retired to his cot, where he would spend much of the next day. His plan was to open an overwhelming attack against the Confederates the following morning, once the other corps had come up and taken their positions.

Buell's careful plan unraveled before he completed it. Since mid-afternoon the Federals had been aware of water in the bed of Doctors Creek. The Confederates on Peters Hill, however, seemed to have vanished. Buell ordered Colonel Speed Smith Fry, a local man, to find out if the rebels were still there. Fry led two companies of the 10th Indiana forward, where they found both the water and the enemy guarding it. Buell and Gilbert ordered Brigadier General Philip Henry Sheridan to send a brigade to drive off the rebels and seize the water. Sheridan handed the assignment to Colonel Daniel McCook, Jr. Around 3 A. M. McCook's un-bloodied brigade moved forward and drove the Arkansans off Peters Hill. At daybreak, Liddell launched a counterattack. As the morning passed, the Peters Hill-Doctors Hill fighting became a vortex, drawing in more units as the battle intensified. When the Federals seized Bottom Hill, Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner implored that Polk send reinforcements, or else withdraw. Finally realizing that he faced a larger force than anticipated, Polk chose withdrawal. Disregarding Bragg's orders to attack, he placed the army in a defensive line. Ironically, Gilbert soon called off Sheridan and ordered him to return to Peters Hill.

Expecting battle, Bragg and his staff arrived in Perryville at about 9:30 a.m., just as the Peters Hill fighting ebbed. An angry argument with Polk ensued. Bragg's ire rose when he rode out to examine Polk's poorly implemented defensive line, which was entirely in the air on the right. Worse, he saw Federal troops moving into position across from the open flank. Bragg had no way of knowing that the troops he saw, two brigades of Brigadier General Lovell Harrison Rousseau's division, I Corps, had no offensive intentions. Chagrined by the tardiness of McCook's and especially Crittenden's corps, an aching Buell had just decided to postpone his assault until the following morning. Still unaware that he faced Buell's entire army minus Sill's divisions, Bragg hastily drew up an attack plan. Major General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham's division anchored the southern sector of the Confederate line. Bragg ordered Cheatham to shift his division north, to not only plug the gap but extend the line beyond the Federal left flank. Cheatham's men, all Tennesseans save one Georgia regiment, double-quicked through town. The rest of the line carefully shifted forward. After an artillery barrage, the Confederates would attack and eliminate the threat. Federal officers saw the dust but optimistically concluded that Polk again was retreating.

At 12:30 p.m., Confederate artillery opened up on the Union line. As the artillery fire slackened almost an hour later, Bragg realized with shock that Polk still was not attacking. Polk explained that more Federal units had arrived in front of Cheatham. This was Brigadier General James Streshly Jackson's division, made up entirely of new recruits. Bragg agreed with Polk's decision to again shift Cheatham to the north, into Walker's Bend, neither man being aware of the almost perpendicular bluffs Cheatham's men would encounter. Bragg filled the gap with two of Brigadier General James Patton Anderson's brigades, commanded by Brigadier General John Calvin Brown and Colonel Thomas Marshall Jones. A few minutes before 2 p.m.., Colonel John Wharton's cavalry rode out to sweep the front. Erroneously he reported that the Federal flank was open. An optical illusion, two hills that perfectly mirrored each other, had convinced Wharton that a Federal battery was on a hill farther south than where he actually saw them. Worse, as he rode back to report to Polk, two Federal brigades, commanded by Colonel John Converse Starkweather and Brigadier General William Rufus Terrill and supported by three batteries, went into line on the hills. Wharton had returned five minutes too early.

So it was that when Brigadier General Daniel Smith Donelson's brigade moved forward from the lip of the Walker's Bend bluffs, over a ridge and into an open valley beyond, it encountered not an open enemy flank but rather a solid blue line of infantry and artillery to its left, front, and right. Particularly galling was the fire of Terrill's eight-gun battery, situated on top of an open knob to the Confederates' right. Federal fire ripped up Donelson's line and eventually compelled the spearheading 16th Tennessee to take cover in a ravine. In an effort to rescue Donelson's men, Cheatham ordered Brigadier General George Earl Maney's brigade to swing north and assault the Open Knob from the front. The rolling terrain initially allowed Maney to approach unseen by the Federals. When they emerged into the open, however, Terrill's artillery, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Parsons', opened up with devastating fire. Maney's assault stalled along the rail fence at the base of the hill. Concerned with losing his guns, at about 2:50 p.m. Terrill launched an ill-advised bayonet charge that only served to weaken his line. Supported by their own artillery, the Confederates surged forward halfway up the hill and then again to its summit around 3:30 p.m., seizing seven of the eight guns.

From the top they now saw two more batteries and a fresh brigade on the ridge to the west, some four hundred yards to the southwest. Between the two lines lay a valley containing a ripe corn field, as well as the Benton (or Dixville) Road, a local route that ran south and southwest until it intersected the Mackville Road at the so-called Dixville Crossroads. That intersection marked the point where I Corps' territory gave way to III Corps. Smashing through the 21st Wisconsin in the corn, Maney's Confederates surged forward, The fighting on what came to be called Starkweather's Ridge became especially vicious, marked by clubbed muskets and hand-to-hand fighting up and down its face. Confederate artillery added to the carnage. Ultimately, the Confederates took the position as Starkweather's men and guns streamed to another ridge to their rear. Joined there by the remnants of Terrill's brigade, the soldiers in Union blue massed behind a stone wall at the top of the ridge. Behind them lay the Dixville Crossroads.

Elements of Brigadier General Alexander Peter Stewart's brigade soon joined Maney, essentially enveloping the latter brigade on the left and right. Unit cohesion broke down as Maney's survivors joined in with elements of Stewart's brigade in pursuit of Starkweather. To their left, the balance of Stewart's men joined with Donelson's survivors to mount an assault from the left. Three combined attempts to drive the Federals off the ridge top failed before Cheatham's Confederates admitted defeat around 4:30 p.m. and fell back to Starkweather's Ridge. The Federals at "Last Stand Ridge," sometimes called "the High Water Mark of the Western Confederacy," had successfully defended the vital crossroads from the northwest.

Cheatham's Confederates were not the only units striving to seize the crossroads, however. Bragg had envisioned an all-out attack en echelon once Cheatham opened the assault. All afternoon, as Cheatham's men drove forward, other Confederates just to the south launched attacks as well. The first, ordered by Thomas Jones, ended in disaster when his Mississippians encountered heavy Federal resistance at the lip of a sinkhole. The right regiments of Colonel Samuel J. Harris's brigade inflicted such casualties there that Jones was done for the day.

To Jones' left, Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson also encountered heavy resistance, as well as interference from Simon Bolivar Buckner. Union Brigadier General William Haines Lytle occupied the hills just to the west of the Squire Bottom House, with Colonel Leonard A. Harris's brigade to his left. So confident had been the Union brass in a Confederate retreat that units had been allowed to move forward into the bed of Doctor's Creek to boil water and make coffee. The 42nd Indiana was still in the creek bed when Johnson's first line struck. Confused by contrary orders from Johnson and Buckner, as well as friendly fire from Brigadier General Daniel Weisiger Adams's brigade to the south, Johnson's assault came apart along the creek bank and Squire Bottom's stone fences. After 3 p.m., the Confederates launched a second effort. While Adams' Louisianans flanked the position, Brigadier General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne's brigade surged up the Mackville Road, pushing Lytle's exhausted men in its wake. To their right, Brown's brigade moved forward in the sector formerly occupied by Jones, driving Harris's Union brigade to the rear. Colonel George Penny Webster's brigade, supporting Lytle and Harris, collapsed with the death of its commander. As at the stone wall to the north, Federal regiments began massing on the brow of the hill in front of the crossroads, near the large, two-story white house of farmer John Russell. With Cleburne pinned down within seventy-five yards of the position but Adams and Wood still advancing on his flanks, Sheridan's batteries opened a devastating fire at Rousseau's command, stopping the Confederate advance in its tracks and sending Adams' Louisianans back to the Bottom House as the sun began to set to the west. For a time, Brigadier General Sterling Alexander Martin Wood's brigade continued forward, struggling toward the crossroads from the northeast until, nearing the Benton Road, they encountered Colonel Michael Gooding's brigade just moving into position.

Gooding's was a III Corps brigade, and the role that corps had played in the battle was wrought with confusion. For much of the afternoon, units of III Corps to the south impotently had watched the Confederate assault roll against I Corps. Unfortunately, all day winds from the south and west, combined with the rolling nature of the ground, had produced the phenomenon known as acoustic shadow. Two miles west, no one at Buell's headquarters, including the commanding general as well as III Corps commander Gilbert, had heard anything more than artillery, which they attributed to overzealous gunners. Unaware of a battle and lacking information from the front, Buell and his men whiled away the afternoon.

At the spear point of III Corps, Sheridan remained in position on Peters Hill, lacking orders from Gilbert and expecting an attack in his front. That assault came after 3:30 p.m. with Colonel Samuel Powell's small brigade. Ordered to clear the hill of a battery, Powell actually was unaware that it represented the tip of an entire corps. Encountering the enemy, Powell's men hung on for a time before breaking for the rear around sunset. When Powell's retreat began, Sheridan allowed his artillery to again open up in support of I Corps. Meanwhile, Brigadier General Robert Byington Mitchell, commanding a division in III Corps, ordered Colonel William Passmore Carlin's brigade to pursue Powell. Carlin's men chased the Confederates back into town. Simultaneously, two brigades of II Corps under the commands of Colonel. George Day Wagner and Col. Charles Garrison Harker approached the town from the southeast. Sensing a opportunity to roll up Powell as well as Colonel Preston Smith's fresh brigade in town, and thereby sweep into Bragg's rear and cut his lines of retreat, Mitchell plead for support only to be ordered by Gilbert to fall back. Actually convinced that no battle was in progress, both Buell and Mitchell gave up a signal opportunity to change the course of the campaign.

Indeed only after several aides caught up with him en route to the front did Gilbert begin to sense what was happening. Still confused as to the totality of the afternoon's fight, however, he ordered only Gooding toward the crossroads. Taking their positions in the growing darkness, the men of Gooding's 22nd Indiana managed to stop Wood's advance, finally driving them back with bayonets. Desperate to achieve a victory before night, the Confederate general Buckner turned to St. John Liddell's tired men and sent them toward the crossroads. Leonidas Polk joined them. Riding too far ahead, Polk in the gloom encountered the 22nd Indiana of Gooding's brigade Believing Polk to be a Union officer, the Hoosiers were relaxing unawares when Polk ordered Liddell's Arkansans to fire into the blue line point blank. One hundred ninety-five men fell killed or wounded; the 65.3 percent casualty rate in the 22nd Indiana was the highest of any in the battle. Liddell pushed his men into the much-desired crossroads as its defenders retreated into the rough ground to the west, but Polk soon ordered him to fall back at the approach of a second Federal brigade from III Corps, Brigadier General James Blair Steedman's. Gilbert had sent Steedman forward under orders from Buell, who too was beginning to grasp in a limited fashion that his army had been locked in battle. Here the battle ended. The most up-to-date casualty figures, compiled by Perryville historian Kurt Holman, in an unpublished paper, put the battle's total losses at 7,677 soldiers. Confederate losses numbered 532 killed, 2,641 wounded and 228 missing, totaling 3,401 men, or 20.2 percent of the Army of the Mississippi. Union losses totaled 894 killed, 2,911 wounded, and 471 missing. Those numbers make up 7.7 percent of the entire Army of the Ohio, but losses in I Corps reached 25.3 percent. Many of the wounded of both armies died as well over the next several days in and around the town of Perryville.

At his headquarters that evening, Bragg slowly digested reports from the front. Eventually realizing that not only had he faced the bulk of Buell's army, but that much of that army remained fresh and un-bloodied, Bragg made the decision to retreat. Colonel Joseph Wheeler's reports of scattered action all day against II Corps on the Lebanon Road particularly alarmed Bragg. During the night, the Confederates stripped the Union dead of arms and supplies and slipped away to the east. Initially retreating to Harrodsburg, Bragg fell back farther to his supply base at Camp Dick Robinson near Bryantsville. Joined there by Kirby Smith but dismayed at the lack of stores. Bragg finally decided to return to Tennessee. Buell tardily followed, but his lack of enthusiasm for the pursuit eventually led to his replacement on October 24. Found not guilty of charges of dereliction in a military court of inquiry held in Indianapolis, Buell nonetheless never again took the field. His army, now under the command of Brigadier General William Starke Rosecrans, encountered Bragg's army again at the end of the year along Stones River near Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

If you can read only one book:

Noe, Kenneth W. Perryville: This Grand Havoc of Battle. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

Books:

Brown, Kent Masterson ed. The Civil War in Kentucky: Battle for the Bluegrass State. Mason City, IA: Savas Beatie, 2000.

Kolakowski, Christopher L. The Civil War at Perryville: Battling for the Bluegrass. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009.

Sanders, Stuart W. Perryville Under Fire: The Aftermath of Kentucky's Largest Civil War Battle. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012.

Organizations:

Friends of the Perryville Battlefield

A group dedicated to preserving and expanding the battlefield park.

Web Resources:

The Battle of Perryville. This site is dedicated to providing resources about the Battle of Perryville including essays, maps, bibliography etc.

Civil War Trust Perryville page. The Civil War Trust is dedicated to the preservation of Civil War battlefields and includes information about the Perryville battlefield here.

Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site. This is the website of the State of Kentucky dedicated to educating the public about and preserving the battlefield of Perryville.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.