The Battle of the Crater

by Richard S. Slotkin

The Battle of the Crater ended with what may have been the worst racial massacre on any Civil War battlefield.

The Battle of the Crater, July 30, 1864, has gone into the history books as “a stupendous failure.” The Union army suffered four thousand casualties, and wasted a spectacular opportunity to capture Petersburg and end the war before Christmas. Less well known is the fact that the battle ended with what may have been the worst racial massacre on any Civil War battlefield.[1]

In the spring of 1864 the Army of the Potomac had fought its way south at terrible cost, only to be stymied by the impregnable trench lines of Petersburg, the vital railroad junction south of Richmond and the James River. Then the ingenuity of a regiment of Pennsylvania coal miners in Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside’s IX Corps created the opportunity for a breakthrough. The 48th Pennsylvania held the apex of “the Horseshoe,” a forward projection of the Union trenches that came within a hundred yards of a Confederate strong-point known as Elliott’s Salient—roughly in the center of the arc of Confederate trenches that defended Petersburg. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Clay Pleasants, commanding the 48th, was an engineer in civilian life, and had designed and constructed long tunnels for coal mines and railroads. His regiment included a number of professional miners, and many of his men had experience in mining. On June 21 Pleasants, perhaps acting on a suggestion from the ranks, developed a plan for tunneling across the no-man’s-land between the Horseshoe and Elliott’s Salient, planting a mine below the strong point, and blowing it up. The mine explosion would create a wide breach in the Confederate trench line, through which Federal infantry could attack. Beyond Elliott’s Salient was open ground, rising gradually to the low north-south ridge along which ran the Jerusalem Plank Road. If Union infantry could seize and hold that high ground its artillery would command the town of Petersburg and the Confederate army would be split in two.

Pleasants’ proposal was passed up the chain of command to Burnside, who (on June 25) enthusiastically recommended it to Major General George Gordon Meade. But Meade’s chief engineer, Major James C. Duane, dismissed the project as “claptrap and nonsense.” He believed it was impossible to dig a military mine of the proposed length—more than 500 feet from the mine-head behind the front line to the salient opposite. Moreover, even if a breach were effected at that point, the ground was still swept by Confederate batteries located north and south of the salient. Finally, Meade had no faith in Burnside’s military judgment or ability to manage a complex operation. On Meade’s orders, the miners would receive no support from army headquarters.[2]

But Burnside believed in the project and supported it using his own resources. He borrowed a theodolite from a civilian engineer (a personal friend) so Pleasants could triangulate an accurate course for his tunnel. Pleasants and his men improvised tools and drew on their civilian expertise to overcome a series of technical problems and push the digging ahead. By July 16 the tunnel had been driven 511 feet, right up under the Salient, and the men began digging lateral galleries to either side to contain the four tons of gunpowder that would blow up the Confederate battery.

In the meantime, Burnside made plans for an infantry assault to exploit the breach if and when the mine was exploded. The division spearheading the attack would have the most difficult and complex assignment. It would have to pass through or around the crater and the large debris field left by the mine; re-form for attack on the far side; then advance to seize the high ground along the Jerusalem Plank Road against whatever reserves of infantry and artillery the Confederates might have at that point. There were four understrength divisions in IX Corps. Three of them consisted of White troops; but these had been exhausted and demoralized by months of combat and heavy losses. Burnside mistrusted their willingness to advance energetically against enemy entrenchments.

The Fourth Division comprised two brigades of United States Colored Troops. Its units were nearly at full strength, and its men were relatively fresh because they had seen very little combat so far—the soldierly quality of Black troops was considered suspect, so most of their service had been guarding the army’s wagon trains. Burnside thought better of their combat capability, and he knew their morale was better than that of his White divisions. Their lack of combat experience meant they had not been habituated to the idea that trench lines could not be attacked. If their rookie enthusiasm could be tempered by proper training, they would serve for a spearhead. Burnside therefore consulted with the Fourth Division’s brigade commanders in planning the assault, and arranged for the regiments that would lead the attack to receive special training in the maneuvers required to pass the breach and storm the high ground.

Although Meade remained hostile to the plan, General Ulysses S. Grant was willing to consider anything that might break the stalemate, and in early July he took a distant interest in the project. A change in the strategic picture brought that interest to the fore. The month of July saw a Rebel army under Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early driving north through the Shenandoah Valley, threatening an invasion of Maryland and, ultimately, an attack on Washington. Grant was first compelled to send to Washington the reinforcements he had planned to use against Petersburg, and then to reduce his own strength by sending the VI Corps. To press the offensive against Petersburg with reduced forces, Grant would have to make use of the mine. On July 23 he began working with Meade on a plan that would combine the mine explosion with an attack in force at Deep Bottom, on the north side of the James River, to threaten Richmond. If that attack seemed likely to succeed, the mine explosion and an attack by Burnside would be used to hold General Robert E. Lee’s reserves south of the river. If Lee diverted his reserves to block the Deep Bottom attack, then Burnside’s would become the main assault.

Burnside now had the cooperation of Meade’s engineers. The mine galleries were completed and packed with four tons of gunpowder. Fuses were run from the galleries to the mine-head through tubes. Galleries and tunnel were tamped with sand-bags to compress the explosion and drive it upward. Surveys of the Rebel lines from the Union positions suggested that the ground behind Elliott’s Salient was open – devoid of entrenchments—all the way to the ridge-line of the Jerusalem Plank Road; and that there was no continuous entrenchment on that line, only a couple of battery emplacements. Federal plans assumed that once the first line of entrenchments was breached, an assaulting column would have a clear road to the high ground.

That assumption was mistaken. The ground immediately behind the Confederate front line (which could not be seen from Federal observation towers) was a labyrinth of communication trenches, in which reserve troops could rally. There was also a ravine half-way up the slope which could shelter infantry. Moreover, the Confederates were aware that Burnside was mining on their front. For weeks Southern engineers had been probing with countermines to discover the Federals’ target. While those efforts failed, the Confederate command was forewarned of trouble, and reinforced the artillery positions in that sector. In addition to the batteries on the Plank Road, batteries were established five hundred yards south and seven hundred yards north of Elliott’s Salient. An especially large battery was established midway down a spur of higher ground that ran from the Plank Road toward the Union lines. Together these batteries provided interlocking fields of fire across the whole area behind Elliott’s Salient and the no-man’s-land between the lines.

The Confederates were confident in the strength of their positions. The entrenchments on the Petersburg front were extremely strong, and manned by four divisions of veteran infantry, one fronting the Bermuda Hundred peninsula and three in front of Petersburg itself. But what made them impregnable was the fact that behind the front lines Lee had a reserve of four infantry and three cavalry divisions. Even if Union troops succeeded in cracking the front line, the gap could easily be sealed by one or more of these reserve divisions, at heavy cost to the attacking Federals.

Grant would negate that Confederate advantage by a brilliant tactical ploy. On July 28-29 Grant sent 25,000 infantry and cavalry under his most aggressive generals (Major General Winfield Scott Hancock and Major General Phillip Henry Sheridan) north of the James River to Deep Bottom. They attacked with such strength that Lee believed Richmond was in danger, and sent his entire reserve north of the James to defend it. That left only three divisions in front of Petersburg, with no mobile reserve – except three brigades of Major General William Mahone’s Division that could be pulled out of line and marched to a threatened point. That meant that the trenches directly opposite Burnside’s 16,000 infantry (IX Corps and a division from X Corps) were held by 4,400 Confederates in Major General Bushrod Rust Johnson’s Division. The only available reserves were three brigades of Mahone’s Division (about 2,300 men), who would have to be pulled off the front line and would need an hour or more to reach Johnson’s front.

Once Federal intelligence reported that Lee’s reserve had gone north of the James, Grant ordered the mine to be blown and Burnside to make his attack. The Fourth Division was ordered to concentrate behind Burnside’s fourteen-gun battery and prepare to spearhead the assault.

Burnside’s operational plan began to fall apart when, the day before the attack, General Meade forbade the use of the “Colored Division” as the spearhead. Meade did not think Blacks were good enough soldiers, and he feared political repercussions if he gave them so important and dangerous a task. If they failed with heavy losses, Radical Republicans in Congress would condemn him for using Negroes as cannon fodder. And Democratic politicians would condemn him no matter what happened. They were fighting that year’s presidential campaign by whipping up racial animosity, on a platform described by one of its partisans as “the Constitution as it is, the Union as it was, and the Niggers where they are.” Democrats opposed the recruitment and use of Blacks in combat; the more extreme demanded that those already in service be dismissed.[3]

Until that moment Burnside’s handling of the operation had been impeccable. But Meade’s disruption sent him into a funk of confusion and resentment. Instead of making a new plan, he had the commanders of his other three divisions draw lots for the spearhead mission. Chance decreed that Brigadier General James Hewett Ledlie’s First Division should lead—a division exhausted by weeks of constant fighting, with a commander who had literally gotten falling-down drunk in his two earlier battles. In the confusion of changing arrangements Burnside and his staff also neglected to detail engineers to accompany the assault troops, to help them fortify the high ground once they had seized it, and to make pathways through the trench lines so that artillery could be sent forward. So even if Ledlie succeeded in storming the high ground, his ability to hold it would be compromised.

Burnside’s orders called for Ledlie’s men to charge through the breach made by the explosion, and take the high ground along the Jerusalem Plank Road. If they succeeded Lee’s army would be split, and Federal guns would command Petersburg. But Ledlie never gave those orders to his brigade commanders. Instead he told them simply to hold the ground around the breach—and wait for the Fourth Division to assault the heights! It is not clear if Ledlie misunderstood his orders because he was drunk, or deliberately falsified them to evade responsibility for leading the assault.

The mine was scheduled to explode at 3:30 a.m. on July 30, and the fuse was lit—but nothing happened. While the whole operation hung in suspense, and Meade harried Burnside about the delay, Sergeant Harry Reese (the foreman in Pleasants’ operation) and Lieutenant Jacob Douty crawled down the tunnel (which might have exploded in their faces). They found a break in the fuse-line, spliced and re-lit it, then scrambled to daylight.

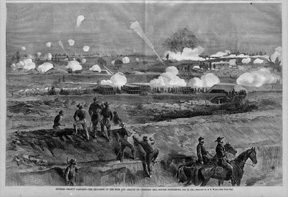

At 4:45 a.m. the earth below the Rebel strongpoint bulged and broke, and an enormous mushroom cloud, “full of red flames, and carried on a bed of lightning flashes, mounted towards heaven with a detonation of thunder.” The explosion blasted a crater 130 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 30 feet deep, with sheer walls of jagged clay. The bottom was “filled with dust, great blocks of clay, guns, broken carriages, projecting timbers, and men buried in various ways . . . some with their legs kicking in the air, some with the arms only exposed, and some with every bone in their bodies apparently broken.” [4]

The effect of the explosion was not what Burnside hoped. The crater itself was an impassable barrier, and the debris-clogged trenches to either side did not permit swift forward movement. A third of Brigadier General Stephen Elliott’s South Carolina brigade, which defended these lines, was destroyed in the blast. But behind the main line Rebel infantry rallied in that labyrinth of communication trenches and the ravine half-way up the slope. On the north side of the breach, Elliott’s survivors were joined by units of Brigadier General Matt Whitaker Ransom’s North Carolina Brigade; on the south side by elements of Wise’s Virginia Brigade. The guns in the ring of well-placed artillery batteries now laid down a heavy cross-fire of canister and case shot that pinned Ledlie’s division in the breach. During the next three hours Burnside’s Second and Third Divisions tried to advance, but those units that assailed the unbroken trenches north and south of the breach were repulsed. The rest piled into the already crowded breach, where they simply added to the logjam around the crater.

At 7:30 a.m., in a last attempt to redeem this disaster, Burnside ordered the Colored Division to charge and carry out its original mission. But after more than three hours of fighting, all the advantages of surprise and shock were gone and Rebel reinforcements were coming up. In order to attack they would have to cross no-man’s-land under fire, then force their way forward through the mass of demoralized White troops around the crater. Nevertheless, their assault accomplished far more than could have been expected. Lieutenant Colonel H. Seymour Hall and Colonel Delavan Bates, commanding the two leading regiments in the first brigade (Lieutenant Colonel Joshua K. Sigfried’s), improvised a pincer attack that drove the Rebel defenders back, and captured 150 prisoners and a clutch of battle-flags. The regiments in the second brigade (Colonel Henry Goddard Thomas’s) also worked their way through the mob and under heavy artillery fire tried to advance, in conjunction with some rallied White regiments.

But by now Rebel reinforcements had arrived, two of the three brigades from Mahone’s Division, and a brilliantly timed and executed counter-attack broke up and routed the attempted Federal advance. Hundreds of troops, Black and White, fled back across the captured sections of the trench line. Small groups of soldiers (Black and White) rallied in the trenches, but too few to stem the Confederate counter-attack. The Federals retreated down the trench line towards the crater, pursued by Confederate soldiers—many of whom murdered the wounded or surrendering Black soldiers in their path. But Mahone’s charge was finally checked by fire from Federals who held the outer berm of the crater and the half-buried trenches around it. With the aid of their artillery, Mahone’s attackers kept the crater position under fire while they waited for Mahone’s third brigade to arrive.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of routed troops and broken organizations, Burnside refused to admit his attack had failed, and rode to Meade’s headquarters to demand reinforcements. The two generals got into a furious argument, which ended in Meade’s peremptory order to withdraw the troops and avoid further casualties. A proper appreciation of the situation would have told them that a successful retreat would require diversionary attacks by other units (since Burnside’s troops were wholly disorganized). However, at 10:30 a.m. Meade and Grant just packed up and left the scene; and instead of developing a plan for withdrawal, Burnside left it to the officers in the crater.

Meanwhile, the troops in the crater were demoralized and trapped in an indefensible position. Between eight hundred and a thousand men were packed into the bottom of the crater, without food or water, in oven-like heat, unable to fight but vulnerable to mortar-fire. A thin line of riflemen defended the crater berm and the trenches to either side. Officers who commanded in the crater testified that Black troops were the mainstay of this last-ditch defense. An enemy, Private Bird of the 12th Virginia gave them the accolade: “They fought like bulldogs and died like soldiers.” They held out under those conditions for three hours.[5]

Then at 2:30 p.m. the Confederates made their final assault. Two of Mahone’s brigades were joined by the rallied survivors of the Elliott’s South Carolinians and Ransom’s North Carolina Brigade. The attackers chanted, “Spare the white man, kill the nigger.” Major Matthew N. Love of the 25th North Carolina wrote, “such Slaughter I have not witnessed upon any battle field any where. Their men were principally negroes and we shot them down untill we got near enough and then run them through with the Bayonet . . . we was not very particular whether we captured or killed them the only thing we did not like to be pestered berrying the Heathens.” Major John C. Haskell of the Branch Battery (North Carolina) observed, “Our men, who were always made wild by having negroes sent against them . . . were utterly frenzied with rage. Nothing in the war could have exceeded the horrors that followed. No quarter was given, and for what seemed a long time, fearful butchery was carried on.” Some of the officers tried to stop the killing, “but [the men] kept on until they finished up.”[6]

As the defense collapsed some White Federals turned against their Black comrades-in-arms, shooting or bayonetting them, because they believed Confederate troops would not grant quarter to Blacks in arms, or to White troops serving with them. As one Union soldier said, “we was not about to be taken prisoner amongst them niggers.”[7]

Their fear was justified. Federal soldiers had seen Rebels killing wounded or surrendering Blacks during the retreat to the crater. Soldiers on both sides believed, with good reason, that the Confederate government sanctioned such killings. The Confederate Congress had declared that officers of the USCT would not be treated as POWs, but criminals fomenting slave rebellion—an offense punishable by death. Fear of Federal retaliation prevented open execution of that policy, but Confederate Secretary of War James Alexander Seddon encouraged field commanders to apply its principles unofficially, “red-handed on the field or immediately thereafter.” There was ample evidence that Rebel troops would do just that. Recent months had seen the notorious massacre of Blacks and their White comrades at Fort Pillow; and North Carolina troops of Ransom’s Brigade had participated in a similar massacre at Plymouth, North Carolina two months earlier. One of Ransom’s soldiers wrote, “it is understood amongst us that we take no negro prisoners,” and another: “it is deth eny way if we got hold of them for wee have no quarters for a negro.”[8]

The killing went beyond the excesses that occur in the heat of battle. Many Black wounded and POWs under escort were shot, bayonetted or clubbed to death as they went to the rear. Confederate Captain William J. Pegram thought it was “perfectly” proper that all captured Blacks be killed “as a matter of policy,” because it clarified the racial basis of the Southern struggle for independence. He found satisfaction in the belief that fewer than half of the Blacks who surrendered on the field “ever reached the rear . . . You could see them lying dead all along the route.”[9]

Not everyone shared in or approved of the massacre. On the one hand, Private Dorsey Binyon of the 48th Georgia regretted that “some few negroes went to the rear as we could not kill them as fast as they past us.” On the other Noble Brooks, another Georgia private, was deeply upset: “Oh! the depravity of the human heart; that would cause men to cry out ‘no quarters’ in battle, or not show any when asked for.” Among the Alabamans, one lieutenant found the killing “heart sickening” and tried to check it. On the other hand, Captain Featherston “apologized” to his wife for having taken the Negroes prisoner instead of killing them: “All that we had not killed surrendered, and I must say we took some of the negroes prisoners. But we will not be held culpable for this when it is considered the numbers we had already slain.”[10]

Most of the eyewitness evidence of the Crater massacre comes from Confederate sources. This is because, on balance, official policy and public opinion approved of the murder of Black troops, so that Confederate soldiers made no effort to conceal the work of massacre—rather, they took pride in describing it. As a further indication of official attitudes, on the day after the battle Confederate military authorities had the IX Corps prisoners—black and white, officers and men, wounded and whole—paraded through the streets of Petersburg to be insulted and humiliated by the citizens—an abuse of prisoners unprecedented in American warfare.

The Battle of the Crater was a hugely disappointing and demoralizing defeat. The opportunity presented by Grant’s successful diversion north of the James and the explosion of the mine was one that would never recur. Burnside and Ledlie were sacked, several subordinate commanders reprimanded. The army and much of the press blamed the Black troops for the breakdown of the infantry attack, although their performance had actually been the best of any of the engaged units. They seized more critical ground, captured more enemy troops, advanced further and suffered heavier losses than any other unit. Ledlie’s white division, which was engaged for nine hours, suffered 18% casualties. The Fourth Division, engaged for less than half that time, lost 31%; and because so many of their wounded were murdered, their ratio of killed to wounded was more than double that of any Federal unit.

The Union armies lost approximately 3,800 men, killed, wounded, missing and captured, at the Crater. Confederate losses are harder to specify, but were between 2,300 and 2,500 at a minimum. However, when the casualties of the Deep Bottom diversion are added in (438 Union, 635 Confederate) the disparity shrinks. Grant could better afford his 4,000+ casualties than Lee his 3,100.

- [1] Ulysses S. Grant, The papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Vol. 2, June 1-August 15, 1864, ed. John Y. Simon. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 361-363.

- [2] William Marvel, Burnside (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 390-1.

- [3] Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War: The Attack on Petersburg on the 30th Day of July, 1864, H.R. Rep. 2d Sess. No. 38-114, at 17, 42, 57 (1865); James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 560.

- [4] Regis de Trobriand, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac, trans. George K. Dauchy (Boston: Ticknor and Co., 1889), 618; Stephen M. Weld, “Petersburg Mine”, Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, vol. 5 no. 10 (Read Before the Society March 27, 1882): 209.

- [5] Gregory J. W. Urwin, ed. Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), 205.

- [6] George S. Burkhardt, Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the Civil War (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007), 168-9; John Cheves Haskell, Haskell Memoirs: The Personal Narrative of a Confederate Officer, eds. Gilbert E. Govan & James W. Livingston (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1960), 77-8.

- [7] Michael A. Cavanaugh & William Marvel. The Petersburg Campaign: The Battle of the Crater, “The Horrid Pit” June 25 – August 6, 1864. 2nd ed. (Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, 1989), 98.

- [8] McPherson, Battle Cry, 566-7; Ervin L. Jordan, Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995), 168.

- [9] Peter S. Carmichael, Lee’s Young Artillerist: William R.J. Pegram (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995), 1301.

- [10] J. Tracy Power, Lee’s Miserables: Life in the Army of Northern Virginia from the Wilderness to Appomattox (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 139.

If you can read only one book:

Slotkin, Richard No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864. New York: Random House, 2009.

Books:

Bernard, Geo[rge] S., ed. War Talks of Confederate Veterans. Petersburg, VA: Fenn & Owen, 1892.

Burkhardt, George S. Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

Cavanaugh, Michael A. and William Marvel. The Petersburg Campaign: The Battle of the Crater, “The Horrid Pit”, June 25-August 6, 1864. Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, 1989.

Hess, Earl J. Into the Crater: The Mine Attack at Petersburg. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010.

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Report of the Committee on the Conduct of the War on the Attack on Petersburg, on the 30th Day of July, 1864. H.R. Rep. 2d Sess. No. 38-114 (1865).

Levin, Kevin. Remembering The Battle of the Crater: War as Murder. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012.

Suderow, Bryce. “The Battle of the Crater: The Civil War’s Worst Massacre,” chap. 9 in Gregory J. W. Urwin, ed., Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Wilson, Keith, ed. Honor in Command: Lt. Freeman S. Bowley’s Civil War Service in the 30th United States Colored Infantry. Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2006.

Organizations:

Petersburg National Battlefield Park

The National Park Service operates the Petersburg National Battlefield Park located near Petersburg Virginia. The park is open daily from 8:30 1.m to dusk and the visitor centers are open daily from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The park is closed on Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. The Park has 4 visitor centers on different parts of the battlefield. Visitor Center telephone numbers are: Grant’s Headquarters at City Point 804 458 9504, Eastern Front 804 732 3531 x200, Five Forks Battlefield 894 469 4093 and Poplar Grove National Cemetery 804 732 3531.

Web Resources:

The Civil War Trust page on The Crater includes basic information, maps, and access to other web sources.

The Siege of Petersburg is a website offering information on the siege.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.