The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854

by Debra L. McArthur

The Kansas-Nebraska Act implemented the concept of popular sovereignty to decide whether to admit Kansas as a free or slave state. Abolitionist and proslavery groups competed for control of the territory that would soon become known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

The groundwork for the blaze that would engulf the United States in civil war was laid long before President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas Nebraska Act on May 30, 1854. Once signed, however, the smoldering conflict of a nation divided over the issue of slavery burst forth like wildfire fanned by the wind across the prairie.

Americans realized their love for freedom when they felt the lack of it under British rule. Some also recognized that the concept of freedom was not limited to white males. In 1774, the First Continental Congress declared that the thirteen colonies would stop importing slaves and would not have trade relations with any country (including Britain) involved in slave trading. Thomas Jefferson’s original version of the Declaration of Independence included a paragraph blaming Britain’s King George III for the introduction of slavery to the colonies. Congress later removed this paragraph. Although the final version of the Declaration of Independence made no mention of slavery, many colonists believed slavery violated the spirit of the words “all men are created equal.”[1]

In just a few years, the people of the United States were clearly divided on the issue of slavery. Plantation owners in the South believed slave labor was necessary for economic survival. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made the processing of cotton, the principal product of the plantations, much easier. The cotton growers enlarged their plantations to meet the demand for more cotton, but they now needed more hands to harvest the crop.

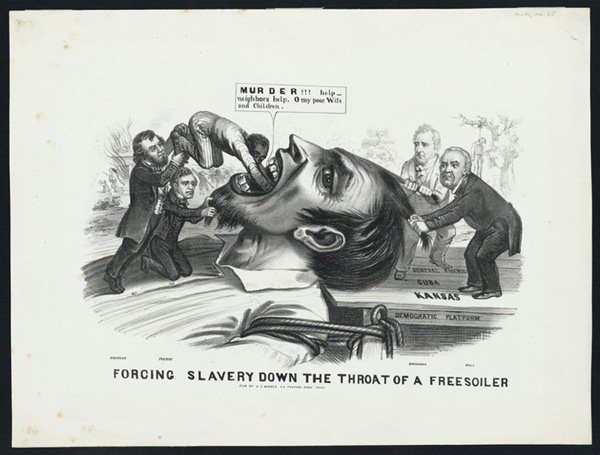

Most Northerners opposed the idea of slavery, but they varied in the strength of their convictions. Some were abolitionists, dedicated to eradicating the practice that began to be referred to as the “peculiar institution.” Others, known as “free soilers,” did not desire to end slavery in southern states, but only wanted to stop the spread of slavery. They hoped that as the United States gained more new territories these new areas would not include slavery.

By 1819, less than half of United States territory had been made into states. Of the twenty-two states established, eleven were free states and eleven were slave states. Since northern states were more populous, they had more votes in the House of Representatives than southern slave states. But the equal number of slave and free states ensured equal power in the Senate, and veto power over any bill passed by the House of Representatives.

Most issues in Congress did not cause conflicts between free states and slave states. When a new bill caused a conflict based on the issue of slavery, however, the balance of power was critical to both sides.

When Missourians asked to be granted statehood, northern senators objected. Missouri had many farmers who owned slaves to work the tobacco and hemp fields. If Missouri became a slave state, then the balance of power in the Senate would tip toward the slave states.

Northerners also objected to Missouri as a slave state because of its location. Missouri bordered Iowa and Illinois, both free states. Slaves who escaped from their masters usually ran toward a free state to become a free citizen there. If caught there by his master or a slave hunter, however, a slave could be arrested and returned to his master. A person who helped a slave escape or helped him to hide from arrest could be sued by the slave’s owner and fined $500 by the court. Conflicts over runaway slaves created many problems in free states located next to slave states.

About the same time Missouri asked for statehood, Maine, which had previously been a part of Massachusetts, also applied. If Maine were admitted as a free state along with Missouri as a slave state, then the Senatorial balance of free states and slave states would be preserved.

In February 1820, Senator Jesse Burgess Thomas of Illinois presented an addition to the statehood bill. His provision would grant admission for Missouri as a slave state, providing that no other slave state could be created north of Missouri’s southern border (thirty-six degrees, thirty minutes north latitude) from any land that had been part of the Louisiana Purchase. Although Southerners did not like the geographic boundary placed on slavery, they agreed to the compromise. Speaker of the House, Henry Clay of Kentucky, helped win approval of the compromise in the House of Representatives. Missouri and Maine were admitted to the union.

In the years following the Missouri Compromise, the balance of free states and slave states in the Senate continued. In 1836 and 1837, Arkansas was admitted as a slave state, followed by Michigan as a free state. Later, Florida and Texas were admitted to the Union as slave states, followed by Iowa and Wisconsin as free states.

Thirty years after the Missouri Compromise, the slavery issue again divided Congress and the nation. As a result of the gold rush of 1848-49, enough people had settled in California to ask for statehood. California was free territory and would be a free state. If California were to be admitted as a free state without making provision for any future slave states, then the South would forever lose its equal voice in the Senate. The controversy was so intense that southern states threatened to withdraw from the Union over it.

Slavery was also an issue in the Southwest. The United States’ victory in the Mexican War had acquired new land to the west of Texas. Texas even claimed that some of this new land was part of its territory. This land west of Texas was mostly south of the line of 36 degrees 30 feet latitude, within the boundary of slavery as set by the Missouri Compromise. However, since that land had not been part of the Louisiana Purchase, it did not fall under the provisions of the Missouri Compromise.

Slavery had been outlawed in Mexico before the war, but if the new territory became part of the slave state of Texas, it would be open to slavery. Northerners did not like the idea of annexing land that had been free and allowing it to permit slavery. Southerners felt that since the land was south of 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude, it should be slave territory, especially since there was no other new land available south of that line to be made into slave states.

Henry Clay, who was now a senator from Kentucky, proposed a plan that offered some benefits to the North and some to the South. To please Northerners opposed to slavery, California was admitted to the Union as a free state. Also, Clay included a measure that ended slave trade in the District of Columbia. To satisfy Southerners whose escaped slaves were being helped by northern abolitionists, the compromise included the Fugitive Slave Act. This measure increased the punishment for helping a slave escape and required all citizens, including Northerners, to return escaped slaves to their masters or else face a fine of $1,000, additional damages up to $1,000 and up to six months in prison. Under Clay’s proposal, Texas would not keep the land to its west, but it would receive a payment of ten million dollars to pay its debt to Mexico from the Mexican War.

Called the Compromise of 1850, Clay’s solution organized the territories of New Mexico (which included both present-day states of New Mexico and Arizona) and Utah. Unlike previous territorial bills, the Compromise of 1850 did not specify that the new territories would be free or slaveholding territories. Instead, Congress agreed to let the residents of the territories decide this issue. They would vote on the issue, and then make their decision part of their constitution when they were ready to apply for statehood. This idea, known as “popular sovereignty,” would soon become even more important.

The Compromise of 1850 did not fully satisfy North or South. Northerners did not like the Fugitive Slave Act portion of the bill. Southerners did not like the laws against slave trade and the imbalance caused by California’s admission as a free state. Still, both sides recognized that without Clay’s Compromise, the United States would be split. After eight months of debate, the bill finally passed both houses of Congress.

Soon after the Compromise of 1850, Americans were still looking for new land to settle. Just to the west of Iowa and Missouri stretched the great plains of the center of the continent. The land here was good for farming, which appealed to new immigrants from Europe and also to those from the more populous eastern states who wanted to find new homesteads. The industries of the North were also making plans for a transcontinental railroad to extend to California. Acquiring this territory would allow the railroad to run a more direct route from Chicago or St. Louis, a route the northern industries preferred.

The first attempt to organize this new territory came to the House of Representatives on December 13, 1852. A Missouri representative, Willard Preble Hall, presented a bill to organize the land known as the Territory of Platte. The bill went to the Committee on Territories, which renamed the area the Territory of Nebraska in the bill it presented on February 2, 1853. Although southern representatives objected to it, the bill still passed in the House and went on to the Senate, where it was defeated on March 3. Since the land was all north of the line of 36 degrees 30 minutes latitude, both North and South assumed that any state formed there would be free. The South was not willing to accept any more free states unless there could be a new slave state as well. [2]

Senator Augustus Caesar Dodge of Iowa made the next attempt on December 14, 1853. He presented a bill to the Senate proposing the organization of the same area as the previous bill. This included land west of Missouri between the lines of 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude and 43 degrees 30 minutes north latitude. The bill was then sent to the Committee on Territories. The head of that committee was Senator Stephen Arnold Douglas of Illinois.[3]

Of course, Southern senators objected to this plan. Therefore, on January 4, 1854, Douglas and his committee presented a revised Nebraska bill. The new bill moved the northern boundary of the territory to 49 degrees north latitude, the northern boundary of the United States. It also included a popular sovereignty provision similar to the wording of the Compromise of 1850, which would allow the residents of the new territory to decide the issue of slavery.

Southern Senators were pleased with the new bill, since it offered the possibility that the new territory could become a slave state, even though it seemed unlikely that slavery would extend as far north as the northern boundary of the United States. Now the senators from the North objected. Since the land proposed for Nebraska territory was part of the Louisiana Purchase and was north of 36 degrees 30 minutes north latitude, passage of this bill would contradict the Missouri Compromise. Northerners considered the Missouri Compromise a solemn promise between the North and South.

Senator Douglas and his committee did not give up on the Nebraska bill. On January 23, 1854, the Committee on Territories presented yet another version of the Nebraska bill. The new version divided the land into two separate territories. Nebraska Territory would make up the northern half of it, extending from the line of 40 degrees north latitude to the United States northern border. Kansas Territory would lie next to Missouri, from the line of 40 degrees north latitude to the line of 37 degrees north (this was moved north from 36 degrees 30 minutes to avoid including tribal land). As in the earlier version, residents in the new territories would decide the issue of slavery. [4]

The most controversial point of the bill, however, was the fact that the popular sovereignty wording of the Compromise of 1850 superseded the Missouri Compromise boundary, and it called that act “inoperative.” In other words, the new bill would repeal the prohibition of slavery as dictated by the Missouri Compromise.[5]

On January 31, Representative William Alexander Richardson of Illinois introduced a Kansas-Nebraska bill to the House of Representatives that was nearly the same as the bill before the Senate. For the next four months, both houses of Congress would be involved in one of the bitterest struggles ever fought there.[6]

The new Kansas-Nebraska Act (often still called by its old name, the Nebraska Bill) opened a new round of debate in Congress. Battle lines were drawn between North and South. The angry voices of northern legislators filled the newspapers. On January 24, the New York Daily Times carried “An Address to the People” signed by both senators and two representatives of Ohio. It called the new Nebraska bill and its repeal of the Missouri Compromise “a gross violation of a sacred pledge,” and predicted that, if passed, it would turn the new territory “into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.” They urged citizens to “protest earnestly and emphatically, by correspondence, through the press, by memorials, by resolutions of public meetings and legislative bodies, and in whatever other mode may seem expedient against this enormous crime.”[7]

Douglas’ motives for presenting the Kansas-Nebraska bill are not clear. One likely reason was business. Many businessmen from Douglas’ home state hoped that Chicago would be the starting point for a railroad route through this new territory. A letter from Douglas to a political committee in St. Joseph, Missouri shows Douglas’ commitment to expand railroads and communication, even at the expense of native peoples:

How are we to develop, cherish, and protect our immense interests and possessions on the Pacific, with a vast wilderness fifteen hundred miles in breadth, filled with hostile savages, and cutting off all direct communication?... We must therefore have railroads and telegraphs from the Atlantic to the Pacific through our own territory…The removal of the Indian barrier and the extension of the laws of the United States in the form of Territorial governments are the first steps toward the accomplishment of each and all of those objects.[8]

Others believed that Douglas was motivated by his own political ambition. An unsigned editorial in the New York Daily Times said Douglas would “sacrifice any public principle, however valuable, and plunge the country into foreign war or internal dissention, however fatal they might prove, if he could thereby advance himself one step towards the Presidential chair.”[9]

If political gain was Douglas’ motive, not everyone thought he was successful. Colonel Thomas Hart Benton, representative from Missouri remarked to a friend, “Douglas, Sir, is politically dead, Sir. If he fail to carry his bill the South will kick him in the rear, Sir; and if he does carry it the North will beat his brains out, Sir.” An editorial in the New York Daily Times agreed, “Two paltry pennies will purchase the political death warrant of the Senator from Illinois.” The Kansas-Nebraska Act would need more than just Douglas’ enthusiasm to be passed by Congress.[10]

Presidential Support

Douglas asked President Franklin Pierce to give his support to the bill. This placed Pierce in a difficult position. Many citizens of his home state, New Hampshire, were against the spread of slavery. They would be opposed to this bill. But, Pierce was also trying to fill political positions in his administration. If he angered southern Senators, they would not approve his candidates. This would be the first major bill Pierce had supported since he became President. If it were to fail, it would make him look weak. Also, Pierce had to consider the unity of the Democratic Party. It was already becoming split between North and South. He dared not provoke Southern Democrats into quitting the party. Pierce decided to support the bill, but it would earn him harsh criticism. An editorial in the New York Daily Times charged Pierce with “plunging the country into renewed agitation of the question of Slavery, which will prove more fatal to the public peace than any similar contest through which the country has thus far passed.”[11]

From the day it was introduced, the Kansas-Nebraska bill took center stage in the Senate. As the publicity over the bill grew, so did the crowds of spectators who came to observe. When Senator Salmon Portland Chase of the Free Soil party of Ohio had his chance to speak against the bill on February 3, 1854, he had a full audience. According to the New York Daily Times, “The galleries and lobbies were densely crowded an hour before the debates began…The entire audience…listened to Mr. Chase’s arguments with profound attention.” [12]

While Senator Douglas and his strongest ally, President Pro Tempore of the Senate, David Rice Atchison of Missouri, (and other supporters of the bill) argued that the Compromise of 1850 had already superseded the slavery provision of the Missouri Compromise, Senator Chase insisted that none of the signers of the 1850 bill had believed that. Chase even referred to a speech Mr. Atchison had made in 1853, in which he had said he would never vote for a Nebraska bill, because, unless the Missouri Compromise was repealed, slavery would not be legal in the territory. At that time, Atchison had said, “But when I came to look into that question, I found that there was no prospect, no hope, of a repeal of the Missouri compromise.” Mr. Chase asked why Mr. Atchison now thought the Missouri Compromise could be judged to be superseded, if he had not thought so the year before.[13]

Most senators from slave states favored the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Since it was clear that northern Congressmen would never admit the new territories as slave territories, popular sovereignty offered the only chance for a new slave state. With many slaveholders living in western Missouri, it seemed likely that some of them would cross the border, settle in the territory, and vote for slavery.

Of course, that same reasoning worried Northerners about the bill. They had assumed, because of the Missouri Compromise that this area would never fall into the hands of slaveholders. In order to have a majority of free-state votes, northern settlers would have to travel through slave state Missouri. How could they get there quickly enough to gain a majority and cast their votes?

Not everyone, however, agreed with these two points of view. Some Northerners, although they did not like the idea of adding a new slave state, did believe that all Americans should have the right to determine the laws under which they lived. One letter to the New York Daily Times argued in favor of popular sovereignty, saying that slavery should be an issue decided by the people in each territory. “Congress would only be following the spirit of the Constitution by leaving the question of slavery…open to the action of the territorial Legislatures.”[14]

As public interest grew, many citizens sent petitions to their congressmen. On February 13, senators presented twenty-six different petitions from citizens of Massachusetts, Vermont, Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania who voiced their opposition to the Nebraska bill. Other public statements, called “memorials,” arrived daily from religious groups all across the North. Many daily sessions of the debate in the Senate began with the readings of these memorials.[16]

The geographical boundary between North and South was not the only dividing line separating the legislators. Political party loyalty was also important. Democrats held the majority in both houses of the thirty-third Congress. The other main party, the Whig Party, held about thirty-three percent of the votes in the Senate, and about thirty percent of the votes in the House of Representatives. A third party, the Free Soil party, held two seats in the Senate and four in the House.[17]

Most legislators were loyal to either the proslavery or free-state opinions of their home states, but they also had to consider their loyalty to their party members from other states. Both Northern and Southern states had congressmen belonging to the Whig Party. Both northern and southern states also had Democratic congressmen. A political party split over the slavery issue could lose many congressional seats in the next election. If the party lost supporters, it would also be difficult to present a successful presidential candidate in the next election. There were many congressional issues besides slavery that a strong party could support. There were few that a weak party could win.

Even Democrats from the South did not all agree. Senator Sam Houston of Texas did not want to repeal the Missouri Compromise. He told the Senate, “For more than a third of a century it has given comparative peace and tranquility…It is the principle of truth that should be preserved. The word of one section of the Union should be kept with the other.”[18]

However, Houston’s fellow Democrat, Senator Andrew Pickens Butler of South Carolina, disagreed with Houston. He said the Missouri Compromise, “instead of bringing with it peace and harmony, has brought with it sectional strife…[I]nstead of being a healing salve, [it is] a thorn in the side of the southern portion of this Confederacy, and the sooner you extract it, the sooner you will restore harmony and health to the body politic.”[19]

Senators from the same state also sometimes disagreed. Senator James Cooper of Pennsylvania argued against the bill, predicting that “its passage will revive all agitation and excitement before experienced on the Slavery question.” Like Senator Houston, he argued that “The Missouri Compromise was adopted as the settlement of dangerous and alarming questions, and for that reason ought not to be disturbed.”[20]

Senator Richard Brodhead Jr., another Whig from Pennsylvania, “regretted that he and his colleague…could not agree upon this measure.” Mr. Brodhead saw no threat to the North because, “Slavery could never go into the Nebraska Kanzas [sic] territories” because the soil and climate were not suitable for the types of crops that required slave labor.[21]

The debate intensified at the beginning of March 1854. Senator John Middleton Clayton of Delaware presented a motion to change the bill by removing a provision that allowed immigrants from other countries to vote in territorial elections. Since immigrants usually did not favor slavery, this would give proslavery voters an advantage in the elections. The motion passed and the amendment was added.

On Friday March 3, the debate continued, although most of the senators were clearly tired of hearing the same arguments. By evening, tempers were running short. Commenting on this final session of debate, the New York Daily Times correspondent described some senators as ill-mannered and even drunken. “A glance from the Senate gallery at midnight on Friday revealed the disgraceful fact, that more than one of its members had forgotten in their cups, all of their dignity and not a little of the propriety of a deliberative body.” The Times correspondent predicted that enough Northern votes would go in favor of the bill to pass it in what he called “a traitorous betrayal of Northern sentiment.” The speeches continued until the next morning, as the senators did not want to adjourn until a vote was taken. Although northern Whigs and Free Soilers voted unanimously against it, both Whigs and Democrats from the South voted almost unanimously in favor of it. Northern Democrats, however, voted 15 for and 5 against. When the final vote was taken, the Nebraska Bill passed 41-17.[22]

From the Senate, the bill moved next to the House of Representatives. Representatives made the same arguments over popular sovereignty and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise as their colleagues in the Senate had made. Both North and South understood that this new territory would probably be the last opportunity for slavery to expand. If that effort failed and the territory became a free state, slavery would probably soon die out when the Congressional balance tipped in favor of the free states.

Those against the bill tried to persuade Southerners that the repeal would violate the honor of the South and those who had supported the Missouri Compromise. It would also lead abolitionists to push even harder to outlaw slavery in all states. They warned Northerners that passage of the bill meant the extension of slavery into northern territories and would create a wide belt of slavery between eastern and western states.

As it had in the Senate, the debate in the House grew louder and angrier as weeks passed. On April 11, Representative William Cullom of Tennessee expressed his impatience with the time spent in debate upon the bill. He called it, “the work of politicians…to strangle the legitimate legislation of the country,” and added, “I should not be a worthy descendent of my mother State, Kentucky, if I did not here, in my place, denounce this scheme as a plot against the peace and quiet of the country, whether so designed or not.”[23]

Representative Phillip Phillips of Alabama spoke on April 24, expressing his support of the bill. He insisted that the South had opposed the Missouri Compromise from the beginning, but had been forced to accept it. Since it was, therefore, not really a compromise at all, Southerners had every reason to support its repeal.[24]

On Monday, May 22, amid much objection and arguing, the representatives voted on the Kansas-Nebraska Act. As in the Senate, Northern Whigs and Free Soilers in the House voted unanimously against it. Northern Democrats, however, were evenly divided, 44 in favor and 44 against it. Seven Southern Whigs voted against the bill; 21 voted for it. It narrowly passed the House of Representatives by a vote of 115 to 104. The House voted to remove the Clayton amendment, so the bill returned to the Senate for one last vote. This time, a majority of Senators voted not to try to add the Clayton amendment again because it would cause the House to reject the bill.[25]

After its passage, New York Senator William Henry Seward addressed the Senate, expressing the intention of abolitionist groups to send settlers to Kansas:

Come on then, gentlemen of the Slave States. Since there is no escaping your challenge, I accept it in behalf of the cause of freedom. We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right.[26]

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed by President Franklin Pierce on May 30, 1854, and became law. The race for Kansas was on, as both abolitionist and proslavery groups prepared to compete for control of the territory that would soon become known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

Just sixteen months later, the Herald of Freedom (Lawrence, Kansas) quoted a piece from the Massachusetts Spy that predicted, “Kansas will probably be the first field of bloody struggle with the slave power. In this country Freedom or Slavery is to predominate. Both cannot live upon an equality, and he who cries Peace, Peace, is only waiting for stronger manacles to be placed upon his own limbs and the limbs of his children.”[27]

- [1]Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 16-17.

- [2] William G. Cutler, “Territorial Organization of Kansas, 1853-54,” in History of the State of Kansas (Chicago: A.T. Andreas, 1883).

- [3] Robert R. Russell, “The Issues in the Congressional Struggle over the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, 1854,” Journal of Southern American History29, no. 2 (May 1963):192.

- [4] Ibid., 196.

- [5] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Proceedings of Congress,” New York Daily Times, January 24, 1854.

- [6] Russell, Issues, 198.

- [7] “Slavery Extension: The Nebraska Bill in Congress,” New York Daily Times, January 24, 1854; Ibid.

- [8] Stephen Douglas to J. H. Crane, D. M. Johnson, and L. J. Eastin, December 17, 1853 in The Letters of Stephen Douglas, ed. Robert W. Johannsen (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961), 270-71.

- [9] “Renewal of Slavery Agitation—The Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, January 24, 1854.

- [10] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 3, 1854; “Northern Sentiment on the Little Giant and his Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 18, 1854.

- [11] “Renewal of Slavery Agitation—The Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, January 24, 1854.

- [12] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Debate on the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 6, 1854.

- [13] Salmon P. Chase, speech before the Senate, Cong. Globe, 33rd Cong. 1st Sess. App. 134 (1854).

- [14] J. W. R. “The Repeal of the Missouri Compromise,” New York Daily Times, January 27, 1854.

- [15] Archibald Dixon, speech before the Senate, Cong. Globe, 33rd Cong. 1st Sess. App. 140-41 (1854).

- [16] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 14, 1854.

- [17] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 14, 1854.

- [18] Sam Houston, speech before the Senate Cong. Globe, 33rd Cong. 1st Sess. App. 206 (1854).

- [19] Andrew P. Butler, speech before the Senate, Cong. Globe, 33rd Cong. 1st Sess. App. 232 (1854).

- [20] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, February 28, 1854.

- [21] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, March 1, 1854.

- [22] “Latest Intelligence from Washington: Prospects of the Nebraska Bill,” New York Daily Times, March 7, 1854; Ibid; Robert R. Russell. “The Issues in the Congressional Struggle Over the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, 1854.” Journal of Southern American History, 29, no. 2 (May 1963): 208.

- [23] William Cullom, speech before the House of Representatives, Cong. Globe, 33rd Cong. 1st Sess. App. 538 (1854).

- [24] “From Washington: Nebraska Movement,” New York Daily Times, April 25, 1854.

- [25] Russell, Issues, 209.

- [26] “Speech of Senator Seward: The Constitution and Compromises,” New York Daily Times, May 27, 1854.

- [27] “The Kansas Struggle,” Herald of Freedom, September 29, 1855.

If you can read only one book:

McArthur, Debra L. The Kansas Nebraska Act and “Bleeding Kansas” In American History. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, 2003.

Books:

Fehrenbacher, Don E. The Slaveholding Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2004.

Russell, Robert R. “The Issues in the Congressional Struggle Over the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, 1854.” Journal of Southern American History 29, no. 2 (May 1963).

Organizations:

Kansas State Historical Society

The Society has an extensive collection of documents, newspapers, images, and artifacts from Kansas history. 6425 SW 6th Avenue Topeka, KS 66615-1099, 785-272-8681

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.