The North Anna Campaign

by Gordon C. Rhea

The third major engagement in the Overland campaign saw Lee entrenched on the North Anna River and Grant, after failing to dislodge Lee, again sidling around Lee's right flank forcing Lee to withdraw to the south.

In the spring of 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. (Hiram Ulysses) Grant initiated a coordinated offensive to defeat the major Confederate armies and bring the rebellion to a close. In the war’s Eastern Theater, Grant launched a three-pronged attack against the rebellion’s premier fighting force, General Robert Edward Lee’s storied Army of Northern Virginia. The Federal Army of the Potomac — commanded by Major General George Gordon Meade and accompanied by Grant — was to spearhead the offensive, supported by smaller armies advancing through the Shenandoah Valley and up the James River. Battered by Meade’s massive Potomac army, denied supplies by the Valley incursion, and harassed in his rear, Lee would finally be brought to bay.

The campaign, however, got off to a faltering start. Crossing the Rapidan River downriver from Lee on May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac became ensnared in a grueling, two-day battle in the inhospitable Wilderness of Spotsylvania. Fought to impasse, Grant directed Meade to withdraw and sidle ten miles south to the cross-roads hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House, expecting that Lee would follow and give battle on terrain more favorable to the Union host. Lee, however, won the race to Spotsylvania Court House and barred Grant’s progress with an imposing line of earthworks. From May 8 through May 18, the Army of the Potomac unleashed a welter of assaults, but Lee’s Spotsylvania line could not be broken. Disheartening news also reached Grant that Confederate forces had defeated his supporting armies. The campaign that had started two weeks before with so much promise seemed about to unravel.

Grant’s and Meade’s relationship was also suffering. Meade’s fumbling management persuaded Grant to keep major battlefield decisions for himself, leaving Meade to handle matters ordinarily relegated to staff officers. The Pennsylvanian’s letters home bristled with hurt. “If there was any honorable way of retiring from my present false position, I should undoubtedly adopt it,” he wrote his wife, “but there is none and all I can do is patiently submit and bear with resignation the humiliation.”[1] Grant’s staffers complained that Meade was uncommitted to the spirit of their boss’s offensives. “By tending to the details he relieves me of much unnecessary work, and gives me more time to think and mature my general plans,” was Grant’s reason for keeping Meade on.[2]

Despite the setback at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant persisted in his grand strategic objective. “This was no time for repining,” he later wrote.[3] The Union drive toward Spotsylvania Court House, disappointing in its outcome, had underscored Lee’s reluctance to let the Federals slip between his army and Richmond. Perhaps the time was again ripe to exploit Lee’s solicitation for his capital. Grant identified Lee’s next likely defensive position as the North Anna River, twenty-five miles south. His choices were to race Lee to the North Anna — a venture rendered problematical by the Potomac Army’s disappointing track record thus far in the campaign — or to entice Lee from his Spotsylvania earthworks by feigning toward the river and pouncing on the rebels when they followed.

Grant’s analysis took into account the terrain that he would have to traverse. Telegraph Road offered the Federal army the most direct path south but required it to cross the Ni, Po, and Matta rivers, risking opposition at each stream; a few carefully positioned Confederates could delay Grant’s progress while Lee’s main body pursued parallel roads and beat him to the North Anna. A few miles east of Telegraph Road, the Ni, Po, and Matta merged to form the Mattaponi, which flowed due south. By swinging east from Spotsylvania Court House, Grant saw that he could circumvent the bothersome streams and descend along the Mattoponi’s eastern side. He would cross only open terrain, and the rivers would work to his advantage, shielding him from attack. In the inevitable race south, Lee, not Grant, would have to cross the irksome tributaries.

To lure Lee into the open, Grant decided to send Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps on a twenty-mile march southeastward through Bowling Green. Once there, the lone Union corps ought to pose too great a temptation for Lee to resist. When Lee left his entrenchments to attack Hancock, Grant would send the rest of his army south along Telegraph Road to crush the rebels. In sum, Hancock would serve first as bait to entice Lee into the open, then as the anvil against which Grant would hammer his opponent. If Lee ignored the bait, Hancock would simply continue to the North Anna River, clearing the way for the rest of the Union army to follow.

Dispatching Hancock toward Bowling Green advanced another of Grant’s objectives. During the fighting at Spotsylvania Court House, provisions had traveled by boat down the Chesapeake Bay from Washington to docks at Belle Plaine, north of Fredericksburg, and on to the army by wagon. As the army moved south, Port Royal on the Rappahannock River became the next logical depot. Ships could reach the town from Chesapeake Bay, and a good road ran to Bowling Green, near Grant’s potential routes.

Grant’s preparations were interrupted on May 19, however, when the Confederate Second Corps under Lieutenant General Richard Stoddart Ewell launched a reconnaissance-in-force to cut the Union supply line along the Fredericksburg Road and to harass the Federal force’s northern flank. The Northerners guarding the road belonged to heavy artillery regiments that had recently arrived from forts around Washington. Novices at fighting rebels, they were stationed on the Harris and Alsop farms, where Ewell caught them unawares, severing Grant’s umbilical cord. “Being novices in the art of war,” an experienced Union man remembered of a Heavy Artillery regiment, “they thought it cowardly to lie down, so the Johnnies were mowing them flat.”[4]

Veteran Union troops rushed to the endangered area, and Ewell retreated, bringing the Battle of Harris Farm to a humiliating end for the Confederates. Union losses were high, but the Heavy Artillerists won accolades. “After a few minutes they got a little mixed,” a battle-worn warrior explained to a newspaperman, “and didn’t fight very tactically, but they fought confounded plucky – just as well as I ever saw the old Second [Corps].”[5]

During the night of May 20-21, Hancock began his diversionary march. Tramping through Guinea Station, the Union II Corps crossed the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad and pressed on to Bowling Green. After a rousing reception by the town’s black populace, the troops angled west across the Mattaponi River and dug in a few miles past Milford Station, twenty miles southeast of the armies at Spotsylvania Court House. At the same time, Grant moved Major General Gouverneur Kemble Warren’s V Corps to Telegraph Road at Massaponax Church, positioned to pounce on whatever force Lee sent against Hancock.

As May 21 progressed, Lee learned of the Union movements and erroneously concluded that the enemy meant to march south along Telegraph Road on a bee-line to Richmond. To counter Grant’s expected move, Lee rushed Ewell east to Stanards Mill, where Telegraph Road crossed the Po. The bold deployment threw a monkey wrench into Grant’s plan by severing Hancock from the rest of the Union army.

Grant began to worry. He had heard nothing from Hancock — rebel cavalry controlled the countryside toward Milford Station — and Ewell’s Confederates were entrenching on Telegraph Road. Concerned for Hancock’s safety, Grant directed the rest of Meade’s army to evacuate Spotsylvania Court House. Warren was to follow Hancock’s route to Bowling Green while the remainder of the army — Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside’s IX Corps, and Major General Horatio Gouverneur Wright’s VI Corps — pushed south on Telegraph Road in an effort to overwhelm Ewell. Once again, an operation that Grant had begun as an offensive thrust was assuming a decidedly defensive tone.

Nightfall saw a Union army in disarray. Near Milford Station, Hancock, isolated from the rest of the Union force, sparred with a body of Confederates sent from Richmond to reinforce Lee. On Telegraph Road, Burnside probed south but was brought up short by Ewell’s defenses at Stanards Mill. Turning around, Burnside’s men became entangled with Wright’s troops in their rear, creating a messy traffic jam. Warren’s corps meanwhile followed in Hancock’s footsteps, stopping for the night at Guinea Station. Some of the V Corps circled back toward Telegraph Road and encamped near Nancy Wright’s Corner, within ear-shot of the critical highway.

Lee still had no clear idea of Grant’s intentions, but the evidence suggested a Union move south. The next defensive line was the North Anna River, and Lee started that way, sending Ewell and Major General Richard Herron Anderson’s First Corps along Telegraph Road and Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps along other roads to the west. All night, Confederates tramped through Nancy Wright’s Corner, passing close by Warren’s sleeping soldiers. Lee, unaware of the Union army’s proximity, unwittingly placed his troops in tremendous peril. And Grant, oblivious to the fact that Lee was filing past his recumbent soldiers, let the Confederates escape unhindered. This was the chance to catch Lee’s army outside of its entrenchments that Grant had been seeking, and it slipped through his fingers. “Never was the want of cavalry more painfully felt,” one of Warren’s aides fumed when he learned of the mistake. “Such opportunities are presented once in a campaign and should not be lost.”[6]

The Army of Northern Virginia’s road-weary troops crossed the North Anna on May 22 and encamped a few miles south of the river at Hanover Junction, where the Virginia Central Railroad crossed the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac line. Lee’s concern was to protect this critical rail link and supply route.

Grant pushed south in Lee’s wake. Unable to gather intelligence because his cavalry was still absent on an expedition toward Richmond, he felt cautiously ahead, with Warren, Wright, Burnside, and Hancock stretched along a moving front. That evening, Grant and Meade camped in the Tyler family yard north of Bethel Church. Visiting the Tyler home, Burnside asked Mrs. Tyler whether she had ever seen so many Yankee soldiers. “Not at liberty, sir,” she answered, provoking a round of laughter.[7]

Lee remained unsure about Grant’s intentions. If the Union army advanced along Telegraph Road, Lee had chosen the right spot to intercept it. But if Grant followed a more easterly route, as Lee suspected he might, the Confederates would have to shift quickly to the east. And so Lee waited for signs of his adversary’s plans.

Caroline County’s byways sprang alive with blue-clad columns the morning of May 23. Warren pressed south along Telegraph Road, making directly for the North Anna; Wright followed closely behind; several miles east, Hancock abandoned his entrenchments near Milford Station and pursued roads to the southwest, while Burnside brought up the rear. Near noon, the Union army’s scattered elements converged at Mount Carmel Church, a handful of miles above the river. Hancock continued toward the main river crossing at Chesterfield Bridge while Warren took a side road west, intending to cross a few miles upstream at Jericho Mills. Wright was to follow behind Warren, and Burnside was to take another side road to Ox Ford, midway between Warren and Hancock. By day’s end, the Army of the Potomac was slated to come together in a line along the river, with some or all of its troops across.

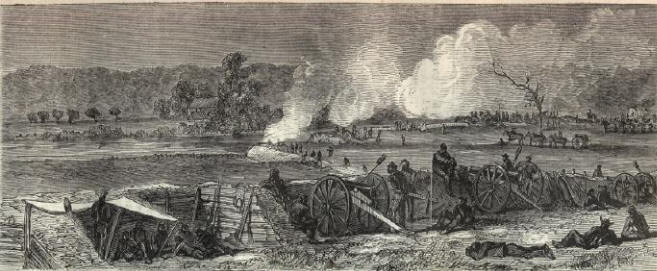

As Hancock’s lead elements neared the North Anna, they came under fire from Colonel John Williford Henagan’s South Carolina brigade. Ensconced in a three-sided redoubt next to Chesterfield Bridge, Henagan’s soldiers were the only Confederate infantrymen north of the river. At 5:30 p.m., Hancock’s artillery opened and Brigadier General David Bell Birney’s division launched a spirited charge. “The Confederate pickets fired, then ran to their fortifications, which instantly began to smoke in jets and puffs and curls as an immense pudding,” a Federal recounted, “and men in the blue-coated line fell headlong, or backward, or sank into little heaps.” Rebel artillery on the southern bank supported Henagan’s Redoubt in “one of the most savage fires of shell and bullets I had ever experienced,” a Union man declared.[8] Union soldiers mounted the ramparts by climbing onto their comrades’ backs and scaling bayonets thrust into the redoubt’s face to form ladders. In short order, the fort and bridge were in Union hands.

Sipping a glass of buttermilk, Lee watched the action from Parson Thomas H. Fox’s porch, south of Chesterfield Bridge. When a round shot whizzed within feet of the general and lodged in the door frame, Lee finished his glass, thanked the parson, and rode away.

Five miles upstream, Warren’s corps dispersed a handful of rebels at Jericho Mills and secured a lodgment on the southern bank. Engineers constructed a pontoon bridge, and by 5:00 p.m., the Union V Corps was streaming across and deploying in the neighboring fields, where they lit fires in anticipation of eating. The woods were filled with pigs, brightening the prospects for dinner.

Confederate scouts reported to Hill that only two Union brigades had crossed. Misled about the size of the Federal force, Hill dispatched a single division under Major General Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox to repel the invaders. As rebel yells echoed across the fields and musketry swelled to a roar, Warren’s bummers, cooks, and sundry civilians accompanying the corps darted back toward the river for shelter.

Charging through a swarm of hogs, cattle, and chickens, Wilcox’s troops threatened to overwhelm a stand of Union artillery and cut off Warren’s avenue of retreat. In the nick of time, Colonel Jacob Bowman Sweitzer’s brigade poured “stunning volleys” into the flank of the rebel assault column, and Union cannon opened fire. “Grape and canister from the smooth-bores and conical bolts from the rifles went through the rebel ranks,” a Union man reported. “I have seen patent mince-meat cutters with knives turning in all directions, but this double-angled line of fire exceeded them all.”[9] Their attack broken, Wilcox’s men fell back to the railway.

Congratulations flowed freely in Union camps; Hancock had secured Chesterfield Bridge and Warren had won a handy victory at Jericho Mills. “We fell far short of our usual success, and infinitely below the anticipations with which we entered the battle,” a Southerner observed of the debacle at Jericho Mills.[10] Lee recognized that he was in serious trouble, now that a formidable portion of Grant’s army stood on his side of the river, threatening his western flank. Was it still possible to defend Hanover Junction, the Confederate commander asked an assemblage of his generals that evening? Was retreat the only option?

Meeting with his chief engineer, Lee came up with an ingenious plan. The Army of Northern Virginia would deploy into a wedge-shaped formation, its apex touching the North Anna River at Ox Ford and each leg reaching back to a strong natural position. This massive salient had none of the drawbacks of the salient that had brought Lee to grief at Spotsylvania Court House; the Mule Shoe’s blunt apex had fronted an open field, inviting attack, while the tip of the North Anna salient rested on precipitous bluffs and was unassailable. And with the Virginia Central Railroad connecting the two feet of the inverted V, Lee could shift troops from one side of the wedge to the other as needed.

Lee also predicted that when the Federals advanced, his wedge would split their force. Then he could spring his trap, using a few troops to hold one leg while concentrating his army against the Federals facing the other leg. Lee had cleverly suited the military maxim favoring interior lines to the North Anna’s topography and given his smaller army an advantage over his opponent.

All night, Lee’s troops threw up earthworks that rivaled their best efforts at Spotsylvania Court House. Hill’s Third Corps deployed along the ridge from Anderson’s Tavern to Ox Ford, forming the rebel wedge’s left leg, and Anderson’s First Corps took up the formation’s right wing, angling back toward Hanover Junction. Ewell tacked onto the right end of Anderson’s line and placed the rest of his corps in reserve, where it was joined by a division under Major General John Cabell Breckinridge, fresh from its victory in the Valley.

May 24 began hot and muggy. Lee was ill with dysentery but tried to conceal his condition to avoid alarming his subordinates. A doctor noted that the general had not slept two consecutive hours since the Wilderness and was “cross as an old bear.” Hill received the brunt of the general’s ire. “General Hill, why did you let those people cross here,” Lee snapped in questioning Hill about his dismal performance the previous evening at Jericho Mills. “Why didn’t you throw your whole force on them and drive them back as [Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan. “Stonewall”] Jackson would have done?”[11] Lee’s reproach must have cut deeply, but Hill held his tongue.

To Grant, it seemed that the Confederates were retreating. “The general opinion of every prominent officer in the army on the morning of the May 24,” a highly placed official recalled, “was that the enemy had fallen back, either to take up a position beyond the South Anna or to go to Richmond.”[12] At daylight the entire Union army — the left under Hancock at Chesterfield Bridge, the center under Burnside at Ox Ford, and the right under Warren and Wright at Jericho Mills — made ready to push south, right into the trap that Lee had set for them.

As the day warmed, Grant and Meade rode to Mount Carmel Church. “The enemy have fallen back from North Anna,” Grant effused in his morning dispatch to Washington. “We are in pursuit.”[13] Meade shot a letter to his wife with the good tidings. The rebels had been maneuvered from Spotsylvania Court House, he crowed, “and now [we] have compelled them to fall back from the North Anna River, which they tried to hold.”[14]

Assured by his superiors that Lee had retired, Hancock started across Chesterfield Bridge, but Confederate artillery contested his advance. “Though the rebels kept up a constant fire of shot and shell the crossing was effected without serious loss,” a Union man wrote, “which seemed miraculous, for one fair shot striking the bridge would have been sufficient to render it impassible.[15] Reaching Parson Fox’s home, Hancock’s Federals waited for the rest of their companions to cross.

Early in the afternoon, Burnside sent a brigade under Brigadier General James Hewett Ledlie across the North Anna upriver from Ox Ford with orders to dislodge the rebels holding the heights. There he found an impressive array of earthworks occupied by a veteran rebel division under Brigadier General William Mahone.

A political appointee, Ledlie recognized that breaking the Confederate hold on Ox Ford would advance his career. He was also fond of whiskey, and witnesses reported him drunk that day. His judgment clouded by ambition and alcohol, Ledlie decided to storm Mahone’s works. A besotted Ledlie rode into the field accompanied by an aide twirling a hat on the point of his sword. Two lines of soldiers advanced behind them, and dark clouds heralding rain gathered in the west. “Come on, Yank,” rebels lining the works shouted, amazed that anyone would consider charging their stronghold. “Come on to Richmond.”[16] As a playful warning, a rebel sharpshooter put a bullet through the aide’s hat.

Ledlie rode on, his men coming behind in orderly lines. Musketry and artillery raked the field, rain fell in sheets, and Ledlie abandoned all pretense of command, leaving his men to their fates. After suffering severe losses, the remnants of Ledlie’s brigade retreated. “Nothing whatever was accomplished, except a needless slaughter,” a Union officer observed, “the humiliation of the defeat of the men, and the complete loss of all confidence in the brigade commander who was wholly responsible.”[17] Astoundingly, Ledlie escaped censure and a few weeks later received command of a division, where he would cause even greater mischief.

Hancock meanwhile probed south, but Anderson’s strongly entrenched position on the wedge’s eastern leg brought him up short. More Federals marched south along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railway east of Telegraph Road only to come under heavy fire from Ewell’s Confederates. Ever optimistic, Hancock informed headquarters that his skirmishers were “pretty hotly engaged” but held onto the fiction that Lee’s main body of troops had retreated.[18] Assuming that he faced nothing more than a holding force in rifle pits, he promised to try and break through.

Lee’s moment had come. His plan to split the Union army had worked, leaving Hancock isolated east of the Confederate position, Burnside north of the river at Ox Ford, and Warren and Wright several miles to the west, near Jericho Mills. Hill, holding the Confederate formation’s western leg, could fend off Warren and Wright while Anderson and Ewell, on the eastern leg, attacked Hancock with superior numbers. “[Lee] now had one of those opportunities that occur but rarely in war,” a Union aide later conceded, “but which, in the grasp of a master, make or mar the fortunes of armies and decide the result of campaigns.”[19]

The general, however, was unable to exploit his opportunity. Wracked with violent intestinal distress and diarrhea, he lay confined to his tent. “We must strike them a blow,” a staffer heard Lee exclaim. “We must never let them pass us again. We must strike them a blow.”[20]

But the Army of Northern Virginia could not strike a blow. Lee was too ill to direct the complex operation, and his top echelon had been decimated. Anderson was new to his post and had much to learn; Ewell had forfeited Lee’s trust at the Mule Shoe and again at Harris Farm; and Hill had exercised poor judgment at Jericho Mills. Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, whom Lee had given elevated command following Stonewall Jackson’s mortal wounding at Chancellorsville, had been killed during his battles to halt the Federal cavalry raid toward Richmond. Physically unable to command and lacking a trusted subordinate to direct the army in his stead, Lee saw no choice but to forfeit his hard-won opportunity.

While Lee lay prostrate on his cot, Hancock made a final lunge. Pressing across the Doswell farm, he came under stiffer fire than before and bivouacked on the rain-soaked battlefield. Warren’s and Wright’s soldiers, massed between Jericho Mills and the Virginia Central Railroad, also advanced but ran against Hill’s entrenched position and threw up earthworks across from the rebels. “To raise a head above the works involved a great personal risk,” a Union soldier remembered, “and as nothing was to be gained by exposure, most of the men wisely took advantage of their cover.”[21] Well entrenched, the Confederates considered the afternoon’s work little more than a routine set of skirmishes. Nowhere had the Federals seriously threatened their line.

Near nightfall, Grant and Meade rode to the Fontaine house, south of the river. Grant had intended to continue his advance in the morning, but the day’s reverses disturbed him. “The situation of the enemy,” he wrote, was “different from what I expected.”[22]

The next morning — May 25 — Union infantry probes confirmed that the rebels commanded killing fields every bit as imposing as those at Spotsylvania Court House. “The conclusion that the enemy had abandoned the region between the North and South Anna, though shared yesterday by every prominent officer here, proves to have been a mistake,” a Federal noted.[23] “The situation,” one of Meade’s aides observed, was a “deadlock,” with the two armies pressed closely together like “two schoolboys trying to stare each other out of countenance.”[24] Another Union man remarked that “Lee’s position to Grant was similar to that of Meade’s to Lee at Gettysburg, with this additional disadvantage here to Grant of a necessity of crossing the river twice to reinforce either wing.”[25]

A Union newspaperman observed that the “game of war seldom presents a more effectual checkmate than was here given by Lee.”[26] But the Confederate commander was also stymied. Ensconced in his earthworks with the Union army pressed tightly against his formation, the only direction he could turn was south, toward Richmond. Having no other choice, Lee forfeited the initiative to Grant and awaited his enemy’s next move.

That evening, Grant and Meade conferred with their generals over how to break the impasse. Some argued that a maneuver west of Lee would catch the rebels off guard. Grant, however, decided that his need to bring in supplies along the tidal rivers required keeping east of Lee. Virginia’s geography also recommended an eastern shift. Below the North Anna, the Union army would face three formidable steams — Little River, New Found River, and the South Anna River — each running west to east and only a few miles apart. High-banked and swollen from recent rains, the rivers would afford the retreating Confederates ideal defensive positions. A few miles southeast of Lee’s position, however, the rivers merged to form the Pamunkey. By sidling downstream along the Pamunkey, Grant would put the bothersome waterways behind him at one stroke. And White House Landing, the highest navigable point on the Pamunkey, was ideally situated as Grant’s next supply depot.

Another consideration favored swinging east. As the Federals followed the Pamunkey’s southeastward course, they would slant progressively nearer to Richmond. Grant’s most likely crossings — the fords near Hanovertown, thirty miles southeast of Ox Ford — were only eighteen miles from Richmond; once the Army of the Potomac was over the Pamunkey, only Totopotomoy Creek and the Chickahominy River would stand between it and the Confederate capital.

Having decided on his next move — withdrawing to the northern bank of the North Anna, powering nearly thirty miles downriver, and crossing the Pamunkey near Hanovertown — Grant penned an optimistic dispatch. The decisive battle of the war, he predicted, would be fought on the outskirts of Richmond, and he had no doubt about the outcome. “Lee’s army is really whipped,” he assured Washington. “I may be mistaken, but I feel that our success over Lee’s army is already insured.”[27]

Grant’s plan was not without its critics. “Can it be that this is the sum of our lieutenant general’s abilities?” an artillerist asked. “Has he no other resources in tactics? Or is it sheer obstinacy? Three times he has tried this move, around Lee’s right, and three times been foiled.”[28]

By everyone’s estimate, the most hazardous phase of the operation would be disengaging from Lee. Not only were the armies pressed tightly together, but they were on the same side of the North Anna, with Grant backed against the stream. As soon as Lee discovered that the Federals were leaving, he was certain to attack, and the consequences could be catastrophic. The worst scenario involved Lee catching the Union force astride the river, unable to defend itself.

Grant’s solution was to use his cavalry, recently returned from its Richmond expedition, to mislead Lee about his intentions. On the morning of May 26, Brigadier General James Harrion Wilson’s mounted division was to ride west of the Confederates and create the impression that it was scouting the way for an army-wide advance. While Wilson practiced his diversion, Brigadier General David Allen Russell’s division of Wright’s Corps was to re-cross the North Anna and march rapidly east, aiming to secure the Hanovertown crossings. After dark, the rest of the Potomac army was to steal from its entrenchments in a carefully orchestrated sequence. If everything went according to plan, the main Federal body would be streaming across the Pamunkey late on May 27 or early the next day.

May 26 saw more rain, forcing both armies to hunker low behind earthworks slippery with mud and knee-deep in water. By noon, Wilson’s cavalry was crossing at Jericho Mills and setting out on its diversion. Reaching Little River west of Lee, Wilson’s men put on a conspicuous show. “To complete the deception,” a Union man remembered, “fences, boards, and everything inflammable within our reach were set fire to give the appearance of a vast force, just building its bivouac fires.”[29]

Russell’s infantry meanwhile re-crossed the North Anna and started toward the Pamunkey. All day, wagons carried the army’s baggage over the river and returned for fresh loads. Sightings of this constant wagon traffic persuaded Lee that the Union commander was planning some sort of movement, and Wilson’s cavalry activity suggested that a shift west was in the making. From “present indications,” Lee wrote the Confederate War Secretary, Grant “seems to contemplate a movement on our left flank.”[30] Wilson’s ruse had worked to perfection.

Shortly after dark, Meade began evacuating his entrenchments in earnest, concealing his departure with clouds of pickets. “Such bands as there were had been vigorously playing patriotic music, always soliciting responses from the rebs with Dixie, My Maryland, or other favorites of theirs,” a Union man noted.[31] Blue-clad soldiers marched along rain-soaked trails in the pitch black, slipping in mud “knee deep and sticky as shoemaker’s wax on a hot day,” a participant recalled.[32] Miraculously, the last of the Federals were north of the river by daylight. Engineers pulled up the pontoon bridges and a Union rearguard set fire to Chesterfield Bridge in hope of delaying pursuit.

By sunup, Lee understood that the Federals had gotten away and were marching east. Uncertain of Grant’s precise route, the Confederate general decided to abandon the North Anna line and shift fifteen miles southeast to a point near Atlee’s Station, on the Virginia Central Railroad. This would place him southwest of Grant’s apparent concentration toward Hanovertown and position him to block the likely avenues of Union advance.

In a masterful move, Grant had turned Lee out of his North Anna line in much the same manner that he had maneuvered the Confederate from his strongholds in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania Court House. Seldom mentioned by historians, Grant’s bloodless withdrawal from the North Anna and his shift to Hanovertown rank among the war’s most successful maneuvers. But Lee’s response was equally cunning, as it enabled him to confront Grant head-on along a new line of his selection, blocking the approaches to Richmond. The chess game between these two masters

- [1] George G. Meade to wife, May 19, 1864, George G. Meade Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- [2] Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (New York: The Century Company, 1897), 115.

- [3] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant (New York: Charles Webster, 1885), 2, 239.

- [4] John W. Haley , The Rebel Yell and the Yankee Hurrah: the Civil War Journal of a Maine Volunteer Ruth L. Silliker, ed. (Camden, Maine: Down East Books, 1985),160.

- [5] Joel Brown, “The Charge of the Heavy Artillery,” The Maine Bugle, Campaign I (1894): 5.

- [6] Washington A. Roebling’s Report, Gouverneur K. Warren Collection, New York State Library and Archives.

- [7] Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 139.

- [8] Frank Wilkeson, Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1887), 114; Charles H. Weygant, History of the 124th Regiment New York State Volunteers (Newburgh, New York: Journal Printing House, 1877), 343.

- [9] Amos M. Judson, History of the Eighty-third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers (Erie, Pennsylvania: B.F.H. Lynn, 1865), 208; Carlton to Editor, May 26, 1864, Boston Evening Transcript, May 31, 1864.

- [10] J.F.J. Caldwell, The History of a Brigade of South Carolinians, First Known as Gregg’s, and Subsequently as McGowan’s Brigade (Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1866), 155.

- [11] Jedediah Hotchkiss to Henry Alexander White, January 12, 1897, Jedediah Hotchkiss Collection, Library of Congress; William McWillie Notebook, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

- [12] Charels A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton,1899), 203.

- [13] Ulysses S. Grant to Henry W. Halleck, May 24, 1864, United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 36, part 3, p. 145 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 36, pt. 3, 145).

- [14] George G. Meade to wife, May 24, 1864 in The Life and Letters of George Gordon Mead, ed., George G. Meade (New York: Scribner’s, 1913), , II, 198.

- [15]Thomas D. Marbaker, History of the Eleventh New Jersey Volunteers (Trenton, New Jersey: Trenton, MacCrellish & Quigley, printers, 1898), 184-85.

- [16] John Anderson, The Fifty-Seventh Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (Boston: E. B. Stillings, 1896), 101.

- [17] Ibid., 104.

- [18] Winfield S. Hancock to Seth Williams, May 24, 1864, O.R., I, 36, pt. 3, 152.

- [19] Adam Badeau, Military History of General Ulysses S. Grant (New York: D. Appleton, 1881), 2: 235.

- [20] Charles C. Venable, “The Campaign from the Wilderness to Petersburg,” Southern Historical Society Papers, 14 (1876 – 1944), 535.

- [21] J. L. Smith, The Corn Exchange Regiment: History of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers (Philadelphia: J.L. Smith, 1888), 444-45

- [22] Ulysses S. Grant to Ambrose E. Burnside, May 24, 1964, O.R., I, 36, pt. 3, 168-9.

- [23] Charles A. Dana to Edwin M. Stanton, May 26, 1864, O.R., I, 36, pt. 1, 78-9.

- [24] Washington A. Roebling to Emily Warren, May 24, 1864,Washington A. Roebling Papers, Rutgers University Libraries.

- [25] Isaac Hall, History of the Ninety-Seventh Regiment New York Volunteers (Conkling Rifles) In the War For the Union (Utica, New York: L.C. Childs & Son, 1890), 190.

- [26] William Swinton, Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac (New York: Charles B. Richardson, 1866), 477.

- [27] Ulysses S. Grant to Henry W. Halleck, May 26, 1864, O.R., I, 36, pt. 3, 206.

- [28] Allan Nevins, ed., Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright (New York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1962), 388.

- [29] Louis N. Boudrye, Historic Records of the Fifth New York Cavalry (Albany, New York: S.R. Gray, ., 1865), 134.

- [30] Robert E. Lee to James A. Seddon, May 26, 1864, O.R., I, 36, pt. 3, 834.

- [31] John Bancroft Diary, May 26, 1864, Bentley Historical Library.

- [32] R.W.B. to editor, June 7, 1864, Springfield (Massachusetts) Daily Republican, June 22, 1864.

If you can read only one book:

Rhea, Gordon C. To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13-25, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Books:

Atkinson, C. F. Grant’s Campaigns of 1864 and 1865: The Wilderness and Cold Harbor May 3 to June 3, 1864. London: H. Rees Ltd., 1908.

Dowdey, Clifford. Lee’s Last Campaign: The Story of Lee and His Men Against Grant, 1864. Boston: Little Brown, 1960.

Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: the Virginia Campaign, May – June 1864. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Hess, Earl J. Trench Warfare Under Grant and Lee: Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Humphreys, Andrew A. The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1883.

J. Michael Miller. The North Anna Campaign: “Even to Hell Itself,” May 21-26, 1864. Lynchburg, Va., 1989.

Rhea, Gordon C. and Chris E. Heisey. In the Footsteps of Grant and Lee: The Wilderness Through Cold Harbor. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

Shreve, William P. “The Operations of the Army of the Potomac May 16 – June 2, 1864,” in Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts. 14 vols. Boston: Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, 1881-1918. 4:289-318.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. Bloody Roads South: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May – June, 1864. Little Brown: Boston, 1989.

Organizations:

Blue and Grey Education Society

The Blue and Gray Education Society is dedicated to assisting members in pursuing their intellectual interests and achieving their legacy by revealing our past for our future through the understanding of the War between the States, by interpreting and preserving its battlefields, conducting high quality seminars, promoting and publishing scholarly research and by facilitating worthwhile education endeavors. They can be contacted at 434.250.992; BGES, PO Box 1176 Chatham, VA 24531-1176 USA.

Central Virginia Battlefield Trust

The mission of the Central Virginia Battlefield Trust is to purchase significant Civil War battlefields and landmarks to preserve them in perpetuity and to serve as a facilitator and advocate for battlefield preservation on the local, state and federal level. Tel: 540 374 0900 P.O. Box 3417, Fredericksburg, Virginia, 22402.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.