The Port Royal Experiment

by Ben Parten

The Port Royal Experiment began when Union naval forces captured Port Royal and the surrounding South Carolina Sea Islands in November 1861. White planters abandoned their plantations which were taken over by freed slaves who began farming on self-surveyed plots. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase sent Abolitionist Edward Lillie Pierce to assess conditions at Port Royal. Pierce reported in February 1862 that the former slaves were willing to work as free men and women. Pierce brought a task force of northern abolitionist missionaries, educators and doctors to oversee the development of the community at Port Royal. The militant zeal exhibited by these young abolitionists led to the derisive nickname, the Gideonites, given them by the army after the biblical Gideonites. Friction among the army, cotton agents and Gideonites resulted from the differing objectives of each group. For the Gideonites and the Federal government the Port Royal Experiment would be judged on whether prewar cotton yields obtained under the southern system of bondage could be obtained under the northern system of free labor. While they focused on work as a primary objective, the Gideonites introduced a comprehensive program of adult education and literacy. The army also recruited a volunteer regiment of United States Colored Troops from Port Royal, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, which served successfully in combat. After completing his march through Georgia, Sherman issued an order in January 1865 confiscating all the land on the South Atlantic coastline from Charleston to Jacksonville, and thirty miles inland. The land was redistributed to freed men and women in 40 acre plots held through a possessory claim. However, following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 President Andrew Johnson began implementing his own reconstruction plan. In the process lands sold outright at public auction remained in freed men and women’s hands but those land redistributed by possessory claim were restored to former owners whose title had not been extinguished by the possessory claims, provided they paid taxes and received a pardon. It became clear that radical land distribution was not going to be part of Reconstruction and the Port Royal Experiment withered as reconstruction progressed. The effects of the Port Royal Experiment, combined with Port Royal’s isolation and large African American population, produced a black community that was largely self-sufficient and independent. Men and women worked, children went to school, and local issues were resolved at the cornerstone of the community, the church. The freed men and women of Port Royal also remained politically active until 1895, when South Carolina’s Constitutional Convention voted to disenfranchise African American voters. Thus, the Port Royal Experiment’s status as a model for Reconstruction did not end with the Port Royal Experiment. Well into the the post-war period it remained an exemplar of what might have been had Reconstruction not reversed its course and given way to the white supremacy of Southern home rule.

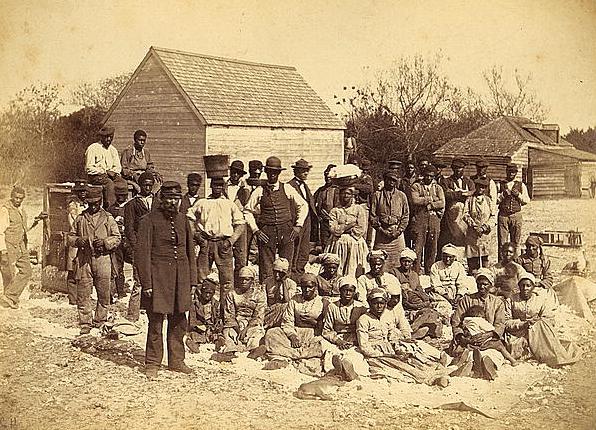

FREED SLAVES, 1862. A Union soldier with the slaves of Confederate general Thomas Fenwick Drayton, on Drayton's plantation in Hilton Head, South Carolina, during the American Civil War. Photographed by Henry P. Moore, May 1862.

Photograph Courtesy of: The Granger Collection # 0120449

The Port Royal Experiment was a humanitarian mission undergirded by economic necessity and military expediency. It was there, in Port Royal and the surrounding South Carolina Sea Islands, that African American slaves first tilled the soil as free laborers. This transformation defied expectations. Both white Southerners and white Northerners except, of course, abolitionists, assumed servitude to be the enslaved person’s natural position. Indolence and ignorance, so the stereotype went, prohibited the African-American worker from being integrated into a free labor system. The experience at Port Royal shattered such assumptions. It revealed that enslaved men and women, if given the opportunity, would work without the lash and develop into responsible citizens. Thus the Port Royal Experiment proved to be what scholar Willie Lee Rose has called a Rehearsal for Reconstruction, for as she maintained, Port Royal operated as vital staging ground where emancipation—and, therefore, the work of Reconstruction—could be tested.

“The Day of the Gun-Shoot at Bay Point”

On November 7, 1861, only seven months after the firing on Fort Sumter, Commodore Samuel Francis Du Pont steered a Union fleet into Port Royal Sound. His mission was to disable the Sound’s two fortifications, Forts Walker and Beauregard on Hilton Head Island and Bay Point respectively, and to lay claim to Port Royal. As the largest deep-water port between North Carolina and the Florida Coast, Port Royal was a natural base for the Union Navy’s South Atlantic fleet, the federal armada that would soon blockade the Deep South’s two prized Atlantic port cities, Charleston and Savannah. But Port Royal’s importance was twofold. In addition to its value as a seaport, it also operated as a vital entrepôt for the region’s famous sea island cotton. Attorney General Edward Bates proposed that if Port Royal could be taken and the surrounding islands secured, the U.S. government could confiscate the remaining cotton wares and sell them to Northern factories. The plan, he suggested, would supply an already beleaguered Treasury Department with ready cash. [1]

The battle was short-lived. The federal fleet pummeled the relatively small Fort Walker, causing the overmatched Confederate force at Fort Beauregard to lower their flag and flee. As Du Pont and his fleet crept slowly up river toward the town of Beaufort, home to some of the most elite members of South Carolina’s plantocracy, they found an abandoned landscape. Upon hearing the first guns around the corner at Bay Point, the area’s white inhabitants had taken flight; their plantations showed signs of a hurried escape. To the local planters, November 7 represented their greatest fear. The supposed “ninety-day war” arrived unannounced at their isolated doorsteps, disturbing, and ultimately ending, their formulaic cycle of planting, profit, and prestige. For their nearly 8,000 slaves, however, “the Day the Gun Shoot at Bay Point” represented something entirely different. [2] It was the day freedom came, and the enslaved men and women celebrated their perceived liberation by repudiating the symbols of their oppression. In what had to have been a moment tinctured with catharsis, “spontaneous acts of self-liberation” broke out on plantations across the islands. “Big houses” were ransacked, gins were destroyed, and, most important of all, self-surveyed plots were partitioned off for future homesteads. As their masters fled for the state’s interior, haunted by the thought of what would become of their old lives, the enslaved people of Port Royal rejoiced in their new lives and contemplated the possibilities that freedom might bring. [3]

Yet liberation was not so simple. Lincoln and his administration insisted that the institution of slavery would not be interfered with. They knew that any outright assault on slavery would make the war a fight for emancipation rather than a war for the preservation of the Union, potentially angering Northern conservatives and precipitating a disaffection of the border states. Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, commanding officer at Fortress Monroe in Virginia, provided a convenient solution saturated in legal subtlety. In May of 1861, six months prior to the landing at Port Royal, Butler granted refuge to three runaway slaves being used in the Confederate war effort. A Confederate officer petitioned for their return, but, after learning that the enslaved men believed they would soon be sold south for military purposes, Butler refused. He declared the slaves “contrabands of war,” a term taken from international law that neither freed the slaves nor recognized their humanity. It merely placed them in the possession of the Federal government. The understanding that it was a war measure only, designed specifically to strike at the productive power of the Confederacy, pacified those Northern conservatives and border states Lincoln dared not alienate. The Confiscation Act of 1861, passed later that August, codified Butler’s contrabands initiative into government policy. The act authorized the seizure of any property, including slaves, being used to aid the Confederates. Thus the enslaved men and women at Port Royal, while free in effect, were formally classified as contrabands, binding them to a liminal state between freedom and bondage.[4]

Salmon Portland Chase, Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury, wasted no time in fulfilling the second half of the Port Royal mission. He immediately dispatched Colonel William H. Reynolds to Beaufort, instructing him to commandeer the remaining cotton wares. But Chase had an idea. As an abolitionist who had made a legal career out of defending fugitive slaves, he knew that certain abolitionists in the North were hoping that the circumstances of Port Royal could be used to advance the cause of black freedom. He also knew that next year’s cotton crop, which he again hoped would help replenish the Treasury Department’s depleted coffers, depended on a working labor force. Therefore, out of his own abolitionist leanings and sense of economic opportunism, he called on Edward Lillie Pierce, the man who had supervised the refugees at Fortress Monroe, and instructed him to go to Port Royal. Pierce’s task was first, to assess the slaves’ conditions, and, second, to see if they would be willing to go back to work.

Pierce filed his official report in February of the following year. In it, he acknowledged that the slaves’ conditions were wanting, but he enthusiastically maintained that they prized their freedom and were quite willing to work. If “properly organized” with “proper motives,” he concluded that “as freemen,” the slaves “would be as industrious as any race of men are likely to be in this climate.” [5] He used the report to propose his own solution. The best course of action, he argued, would be the creation of a free labor enterprise, where white superintendents would manage cotton cultivation and establish schools for the slaves. The freed people would continue working but with two major modifications to the labor regime: they would work as individuals or in family units rather than in gangs and they would be paid for their labor. Pierce’s proposal, at least in his mind, expedited the process of emancipation. If his initiative succeeded, could the government re-enslave men and women proven fit for freedom? If the Government endeavored not to re-enslave them, how could they then justify the continued enslavement of African Americans outside of Port Royal? Secretary Chase, delighted with the report, supported Pierce’s initiative and coordinated a meeting between Pierce and President Lincoln. Though seemingly irritated with Pierce’s zeal, Lincoln acquiesced, giving Chase the authority to instruct Pierce as he wished. Though technically still classified as contraband, the enslaved men and women of Port Royal would henceforth be free men and women according to the terms of the newly christened Port Royal Experiment. [6]

The Gideonites

While Chase fully supported the initiative, there was an additional element of Pierce’s proposal that lay beyond his ability to fund. Pierce had plans to ferry a task force of Northern missionaries, educators, and doctors, whose jobs would be to oversee the creation of Freedman’s schools and houses of worship, provide for the health and well- being of the freed men and women, and, in some cases, to act as plantation superintendents, down to the islands. Chase could ensure their travel and requisition supplies, but he could not fund their entire endeavor. Federal compensation was out of the question, for reasons both political and financial, meaning that Pierce would have to find participants whose own zealous idealism was incentive enough. The member lists of Northern abolitionist and anti-slavery societies were thus the most logical places to look. If the government was interested in only labor and the cotton it produced, Pierce knew that the abolitionists would treat the formerly enslaved with goodwill and institute programs of social uplift, setting their sights on not just free labor but full citizenship and beyond. [7]

Fortunately, some of Boston’s most well respected abolitionists, many of whom knew Pierce personally, agreed to financially support the project at Pierce’s behest. Reverend Mansfield French, a clergyman commissioned to Port Royal by the American Missionary Association (AMA), met Pierce while on the coast and pledged his support for the project. Using his connections with the AMA, French secured patronage from New York’s abolitionist community and created a National Freedman’s Relief Association in the process. Before long, their benefactors in both Boston and New York provided Pierce and French a list of well-qualified recruits from which to choose.

The eager recruits were mostly young, well-educated professionals who had come of age in the 1850s. As a result, for many of the recruits, practical fact rather than moral fervor characterized their experience with abolitionism. They viewed slavery not in the Garrisonian view, which deemed it the most abhorrent of sins, but through the lens of the Free Soil Movement, causing them to understand slavery as a competing system of labor that impeded national progress. Emancipation, they maintained, should thus be approached rationally and done in a way that affirmed certain Northern precepts like the superior productivity of free labor and the value of individual enterprise. [8] Not all of the recruits, however, adhered to this vision. In fact, competing ideals divided much of the group. Some, particularly the older, more evangelical recruits, viewed Port Royal as the culmination of their moral harangues. Accordingly, these men and women felt that their work should better reflect their convictions, which meant that they prioritized humanitarian relief and religious instruction over the promotion of a free labor ethic. This deep internal fissure split the group between its more evangelical members and its adherents to liberal Christianity—a division which Willie Lee Rose suggests “was nothing more than a projection of the cleavages that had developed in American abolitionism.” Overcoming these cleavages would be on ongoing struggle, one that was never quite resolved. [9]

Nevertheless, on March 3rd, 1862, fifty-three New Yorkers and thirty-five Bostonians from disparate backgrounds, professions, and denominations all boarded a steamer bound for the South Carolina coast where they would soon embrace a derisive nickname fashioned for them by the army. Like the biblical Gideonites that came before them, the Northerners were determined to carry their divine commission forward, not allowing their great task to diminish their “militant zeal.” [10]

The Gideonites’ early days at Port Royal constituted a steep learning curve. Not only were they new to their surroundings, but those assigned superintendent positions had little experience with plantation management. They struggled to organize themselves, on one hand, and to convince the freed men and women to return to cotton cultivation on the other. To make matters worse, the white Northerners already on the islands provided very little help. From the moment the first gun-boat landed, the army opposed the slaves they had effectively freed. The reasons varied. Some soldiers believed the slaves to be an impediment to military operations, while others were simply racist, and their racism, combined with some of the soldiers’ own depravity, precipitated a number of crimes against the former slaves. The soldiers exacted a similar, though not quite as base, hostility to the Gideonites, who the soldiers perceived as nothing more than meddling do-gooders.

The zero-sum battle over the islands’ supplies created another confrontation. Under orders to requisition not just the cotton but any salable merchandise adorning the plantations, William Reynolds’s team of cotton agents, according to the common Gideonite charge, purposely obstructed their humanitarian work. It did not help matters that the Gideonites were such poor cotton planters and managers. The agents, many of whom were veterans of the cotton trade, believed the missionaries to be unfit for cotton cultivation and too idealistic toward the freed people. In the end, Reynolds and Pierce, as representatives of their separate missions, fought for Port Royal supremacy, with Chase being the ultimate arbiter. But Secretary Chase decided to wait it out, for Reynolds’s mission would soon be over. The contest over authority would thus continue, with each of the three governmental bodies—the army, the cotton agents, and the Gideonites—believing their objectives should supersede those of the others.

The Freed Men and Women

Cotton cultivation, according to the U.S. government and many of the Gideonites, would be the barometer by which the Port Royal Experiment would be judged. The rationale was simple. A return to prewar cotton yields under a free labor regime would, for one, be proof of free labor’s productive might and, secondly would discredit the notion that cotton could only be efficiently produced if underpinned by a system of bondage. The freedmen and women, however, were reluctant to return to the old staple, presenting a problem for the Gideonites, particularly those who became plantation superintendents. The formerly enslaved men and women viewed cotton, like the plantation homes they sacked and the gins they disabled, as a symbol of their suffering and sought, instead, to ensure both their subsistence and autonomy by planting non-commercial staples like corn and sweet potatoes. Laura Towne, a moral crusader and member of a successive wave of Gideonites from Philadelphia, remembers the freedmen and women “begging Mr. Pierce to the let them plant and tend to corn” rather than cotton, for, as she pointed out, they knew that “their corn has kept them from starvation.” [11] A return to cotton planting, therefore, became the subject of ongoing labor negotiations, with each plantation developing its own expectations and standards for not just how much cotton would be worked but how, when, and where, this cotton would be produced.

The negotiations represented a contest between two competing conceptions of free labor. The former slaves believed their de facto emancipation guaranteed their economic autonomy. As autonomous agents, free to determine their own economic lives, the freed men and women desired to work on their own time and according to their own practices. Wages, the supposed universal incentive propelling production, were cast aside as trivial by many of the freed men and women as their own subsistence proved to be the primary catalyst behind their labor. That the Freed people could have “done so much as they have this year without any definite promise of payment” shocked Edward Philbrick, a particularly paternal and economically minded Bostonian Gideonite. [12] Northerners like Philbrick could not disassociate themselves from the joint Protestant-capitalist ethic in which they had been indoctrinated. Free labor, for them (primarily the troop’s younger and less evangelical members) was not simply a system for freemen but a system that made men free by producing liberation out of subordination. They posited that the free labor system instilled in one the discipline, thrift, and respect for rank and order needed to first attain independence and then preserve it. And because independence begets citizenship, the Northerners’ understood their free labor system to be indispensable to the perpetuation of American democracy.

An outright rejection of the Northern conception of free labor would, by default, be a rejection of a burgeoning American ethic, invalidating the Port Royal mission and discrediting the republican vision the North hoped would be the foundation of the reconstructed South. [13] Therefore, persuading the freed men and women to adopt a labor regime that, if nothing else, resembled the free labor system of the North was of the utmost importance. The labor negotiations were thus not simply about who would work or how one would work but of which republican vision would prevail. Winning the war of ideas hung in the balance, and the freed people of Port Royal had, for the first time ever, a say in not only how their labor would be used but in what the future of their country would look like. Though their hope for economic autonomy would not be immediately realized, by acquiescing to the Gideonites’ veiled paternalism and grudgingly agreeing to return to cotton in some capacity, the freed men and women of Port Royal threw their weight behind a free labor future, levying a decisive blow to the plantation South’s ideological superstructure in the process.

While establishing a level of good will between the white superintendents and the black laborers was a process in the making, an almost instantaneous bond germinated between the white educators and the former slaves. Gideonites William Channing Gannett and Edward Everett Hale observed that, when offered, the alphabet operated as a “talisman” that secured confidence of the freed people, whom, they claimed, expressed an “enthusiastic readiness” for literacy. According to Gannett and Hale, the freed men and women, while purposely kept in a state of ignorance, “knew of the power of letters” and desired to “share such a power.” [14] Creating a pervasive and effective educational program, though, would come slowly. Over time, four different approaches emerged. One approach developed in the Sabbath School, the Port Royal reincarnation of the traditional Sunday school. The only difference was that the classes promoted literacy by way of scriptural study. Another approach was the more standard mixed class, given its name because, while typically only attended by children, it remained open to adults. These classes functioned as day programs that replicated the traditional school environment. A third and far less formal approach occurred when freed men and women demanded individual instruction. In these instances, the white educators would invite the freedmen and women into their homes for private lessons or become itinerant tutors, visiting each freedman or woman’s home upon request.

The fourth and most common approach catered to the specific exigencies of the Port Royal Experiment. Work remained the primary objective, which made any sort of comprehensive program for adult education a difficult task. Therefore, to circumvent the restrictions work placed on the freedmen and women’s educational opportunities, night classes were held as often as three times a week. The sessions started, in some cases, as early as four in the afternoon and ended as late as nine. But even on the nights that did not have a scheduled class, evening education still frequently occurred. [15] Free of the labor responsibilities they had previously known, “nearly every school-child,” became “a teacher in the family,” bringing the lessons he or she learned that day back into their own homes. [16] The freed people saw literacy as a pivotal means of self-protection, but literacy, by itself, was, and is still, not entirely sufficient enough to ensure complete protection. It was, however, the most accessible step toward personal independence. Land ownership, what they believed to be the most critical ingredient to their own freedom, remained, for the time being at least, simply out of their hands.

The issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, altered the course of the Port Royal Experiment. Not only did it grant legal freedom to the already freed men and women of the islands, it authorized the enlistment of black soldiers into the U.S. Army. But for many of the freed men and women, an attempt to incorporate black soldiers into the armed forces was nothing new. On May 9, 1862, Union General David Hunter, commander of the Department of the South, boldly declared the slaves of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida free men. As an addendum to his initial declaration, he ordered all the able bodied men of Port Royal and the surrounding islands to Hilton Head, where they were to be drilled and trained as soldiers. Without any directive from Washington, Hunter instituted his own version of the draft. While many of the former slaves acquiesced, others, particularly the freedmen’s wives, were fraught with panic, thinking that the army had secret plans to sell them to Cuba. The Gideonites fumed with rage. Conscripting the able men, they protested, would drastically reduce the size of their labor force, undermining their attempts to both foster a free labor environment and resurrect Port Royal’s cotton economy. President Lincoln rescinded Hunter’s premature Emancipation Proclamation, but Hunter’s regiment of 500 former slaves continued drilling throughout the summer of 1862 without so much as a word from Washington. Unable to provide a steady wage for his men, Hunter eventually had to disband his troop in early August. [17]

Earlier that April, Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton appointed Brigadier General Rufus Saxton the Military Governor of the Department of the South. The title placed the affairs of both the army and the Port Royal Experiment under his command, which Secretaries Chase and Stanton believed, would only make the Port Royal Experiment stronger by giving it the formal backing of War Department. The move ensured that the contentious power plays between the army, the Gideonites, and the Cotton agents would be no more as the army and Gideonites were now consolidated, at least in theory, into one body.

Saxton, the son of a famous abolitionist writer and a noted anti-slavery man in his own right, hoped to pick up where Hunter left off. In late August, only a few weeks after Hunter demobilized his conscripted regiment, Saxton sent Mansfield French and Robert Smalls, an escaped former slave, and the eventual political leader of the Port Royal community, who famously piloted the Confederate Steamer Planter out of Charleston harbor and into the hands of the U.S. Navy, to Washington. Their orders were to persuade Stanton and Chase to authorize the raising of a new regiment of freedmen, which they did, possibly because both Stanton and Chase knew of Lincoln’s emancipation proposals already in the works. Stanton could now outfit, arm, and, most importantly, pay a new division of black soldiers, but unlike Hunter, Saxton had no plans to impress anyone into service. The only men enlisted would be men who were willing to fight. While many of the freed men and women reacted just as they had to Hunter’s declaration, by the end of the year, he had built a fighting force of close to 800 men, many of whom, it should be noted, were freed men from occupied islands in Georgia, Florida, and elsewhere in South Carolina as well.

The Gideonites, too, initially reacted just they did before, but after witnessing both Saxton’s recruiting successes and his good will toward the freedmen, many of the most skeptical Gideonites came to view the soldiers with pride. They recognized that, in the debates over the freedmen and women that were to come, military service would be a national symbol of black freedom and independence. The freedmen’s success on the battlefield did nothing to discourage the Gideonites, Saxton and his fellow officers, or the freedmen and women of Port Royal themselves. In the summer, Hunter’s old regiment stood toe to toe with Confederate guerilla fighters on an excursion to the Georgia coast. In November, the Port Royal regiment, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, returned to the Georgia sea islands, destroying Confederate works and taking a number of prisoners. Their success spoke for itself. Bearing arms gave the freed men a sense of manhood, self-worth, and independence, and, from the perspective of the federal government, it also hastened the war’s end as it equipped the Union army with a new, and as the Georgia excursions revealed, lethal fighting force. [18]

Land Redistribution and Sherman’s Field Order 15

The Port Royal Experiment was not an isolated endeavor. It sent shockwaves throughout the region and induced slaves to flee toward the coast, resisting their masters and risking their lives in the process. The hope was that freedom would be awaiting them there. Historian Joel Williamson surmises that by the summer of 1862 nearly three thousand refugee slaves had evaded capture and found their way into the occupied islands. By the end of the war, he suggested, “at least thirty thousand” had infiltrated the expanded occupied territories, now stretching sporadically from the outskirts of Charleston to the Savannah River. The large majority of whom, he concludes, were inland refugees. The experiment, in a word, was growing, taxing the management skills of the Gideonites even further. [19]

Permanent settlement was also a question. Despite all that had been accomplished, the Port Royal Experiment would eventually have to cease being an experiment. For Saxton, the freedmen and women, and the Gideonites, the desired outcome featured the resettlement of Port Royal’s freedmen and women as independent landowners. To the missionaries, appropriating the abandoned plantations and dividing then among the freed people represented the only just recompense for the many years they labored there under the lash. The first major step in this direction occurred in June of 1862 when Congress passed a direct tax on the states resisting the civil authority of the United States Government. The tax supplemented a previous act which, in an effort to raise revenue for the war effort, levied a general tax on each state. The 1862 tax also outlined a program wherein tax commissioners were to travel to the states in rebellion and evaluate how much each estate owed based on their property holdings. If the sum, plus an additional delinquent penalty, went unpaid after sixty days’ notice, the commissioners were to confiscate the land and offer it at a public sale.

At first, much of the confiscated land had been encompassed in the Port Royal Experiment. The freedmen and women, many of whom had been the slaves of the original land owners, continued to till the land while the missionaries supervised their work. But by February of 1863, the Federal government decided that the lands should be sold as outlined in the 1862 tax act. In response, three different positions emerged as to how to go about the land sales. The first camp, led by Saxton and supported by a majority of the Gideonites, argued that the land should first be offered exclusively to the freed men and women, who, after an initial deposit, could finance the remaining payments. The contrasting position, led by the tax commissioners sent to evaluate the land, maintained that the property should be sold outright to the highest bidder, whomever that may be. The existential danger of their position, Saxton and the Gideonites protested, was that if sold outright by the treasury department, the land would find its way into the hands of speculators looking to position themselves at the fore of the Sea Islands’ post-war cotton economy. Edward S. Philbrick, a Bostonian businessman and early Gideonite, offered a third position. He argued that the freed people were still unfit for independent landownership. The freed people should thus submit themselves to the paternal oversight of the Gideonites, who, according to Philbrick’s plan, would buy the land and then resale it to the freed people once they were prepared for independence. By what metric Philbrick would judge when they were ready to own the land remains unknown.

The government, however, stuck to the original dictates of the 1862 tax act. The land was to be sold to highest bidder with no questions asked. But Saxton, distressed by how destructive the sales would be to the Port Royal Experiment’s existence, appealed to his superiors and managed to stall the sales based on “military necessity.” Yet despite Saxton’s efforts to stall the sales, the tax commissioners convinced the Federal Government to go through with the sale of forty-seven of the one hundred and ninety-seven confiscated plantations. Of the forty-seven plantations sold, six were sold to freed people (all but one of those six were bought by groups of freedmen and women who had pooled their money together). Eleven were bought by Philbrick, who later subdivided and resold them to a number of freed families and groups of freed men and women. The remaining plantations, some thirty in all, found their way into the hands of speculators. [20]

Yet, when compared to the revolutionary ramifications of Sherman’s Special Field Order 15, the confiscated land sales appear almost inconsequential. Issued on January 16, 1865, less than a month after Sherman completed his famous march through Georgia, Sherman’s Special Field Order 15 confiscated the South Atlantic coastline, from Charleston to the St. Johns River in Jacksonville, ranging from the waters’ edge to thirty miles inland and ordered it to be redistributed to the freed men and women in forty acre plots. To Sherman, the order solved a problem. As he had marched through Georgia, as many as 17,000 refugee slaves had abandoned their homes and followed him to the coast. [21] The confiscated lands known as the Sherman reserve provided those refugees a home, and as Sherman understood it, ensured that they would not encumber him on his march north through the Carolinas. [22]

The stipulations in Sherman’s order resembled the plan Saxton envisioned for the forty-seven plantations sold at public auction. According to the field order, freed families could pre-empt a plot of land at a reasonable price. Settlement would be overseen by military officials who, until a formal title could be written, would provide the freed families a possessory claim to the land. More importantly, however, the order mandated that no white person, unless he or she served as a military or governmental official, should reside on the lands, which meant, of course, that land speculators would not be allowed to intervene. Congress codified the Sherman program into federal law when it passed the Freedman’s Bureau Bill in March 1865. [23]

However, the success of the settlement program would be short-lived. Following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Andrew Johnson, who had already shown signs of being conciliatory to former Confederates, began reneging on the government’s commitment to settlement. Removing white landholders from their title for the sake of African American freedom did not fit into Johnson’s conservative and white supremacist vision of national reconstruction. So long as former Confederates acknowledged emancipation and accepted the primacy of the federal government, he was content to grant amnesty and restore their property, except for the freed people. According to the Johnson plan, Reconstruction was to be short, swift, and dedicated to reconciliation rather than revolutionary social change, leaving the future of the abandoned lands in question.

Over time, however, Johnson’s policy became clear. The lands sold outright at public auctions were safe, but those included in the Sherman reserve were to be restored to their former owners once he or she paid the tax and received a pardon. After all, the freed people who inhabited land within the Sherman reserve only held possessory claims to the land. Legal title remained with the original landholders. Caught between the prerogatives of the president and the protestations of the freed people they had dedicated themselves to, Saxton, the man charged with overseeing land redistribution, and Oliver Otis Howard, the new head of the Freedman’s Bureau, could only stall the restoration process. Their hope was that once Congress convened at the first of the year, the Radical Republicans would be able to both renew and fortify the Freedman’s Bureau Bill, giving it the authority needed to thwart Johnson’s policies. Johnson, however, would not be out maneuvered so easily. In February 1866, he vetoed the bill. Though the radicals repassed the bill later that spring and this time, overrode Johnson’s veto, the new version of the bill lacked the injunctions needed to stop restorations and secure titles for the freed people. The message was understood: Congress, the federal government, and, indeed, the American people were not prepared to make radical land distribution a pillar of reconstruction, signaling to the people at Port Royal that the experiment had entered its final days.

Intense disillusionment set in on both sides. Some of the freedmen and women lost trust in the white missionaries, and Gideonites believed much of their work to have been in vain. Even the educators, who, of all the Gideonites, witnessed the remarkable gains of freedom on a daily basis, were disheartened. The radical takeover of Reconstruction in 1867 revitalized the Port Royalists, but by then, the battle over land redistribution had already been lost. And while the Radical Republicans succeeded in pushing landmark civil rights legislation through Congress, the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments proved fatal for the humanitarian work being done on the sea islands. With African Americans now armed with citizenship and the franchise, Northern support for efforts like the Port Royal Experiment withered. As Rose puts it, “the national obligation to the freedmen had been fulfilled.” [24] One by one the Gideonites left the sea islands.

Contrary to what many may have felt at the time, however, the work at Port Royal had not been in vain. True, Port Royal was subject to the tragic trajectory of Reconstruction, but gains had been made. The effects of the Port Royal Experiment, combined with Port Royal’s isolation and large African American population, produced a black community that was largely self-sufficient and independent. Men and women worked, children went to school, and local issues were resolved at the cornerstone of the community, the church. Taking their cue from their unabashed leader, Robert Smalls, the freed men and women of Port Royal also remained politically active until 1895, when South Carolina’s Constitutional Convention voted to disenfranchise African American voters. Thus, Port Royal’s status as a model for Reconstruction did not end with the Port Royal Experiment. Well into the post-war period it remained an exemplar of what might have been had Reconstruction not reversed its course and given way to the white supremacy of Southern home rule.

- [1] Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 5–6; Orville Vernon Burton, Wilbur Cross, and Emory Campbell, Penn Center: A History Preserved (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014), 9–13.

- [2] Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, 17.

- [3] Burton, Cross, and Campbell, Penn Center, 10.

- [4] James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013), 93–99.

- [5] United States. Department of the Treasury and Edward Lillie Pierce, The Freedmen of Port Royal, South-Carolina. Official Reports of Edward L. Pierce (New York: Rebellion Record, 1863), 308.

- [6] Joel Williamson, After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861-1877, Norton Library ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1965), 9.

- [7] Akiko Ochiai, “The Port Royal Experiment Revisited: Northern Visions of Reconstruction and the Land Question,” The New England Quarterly 74, no. 1 (2001): 94–95.

- [8] Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, 37–40.

- [9] Ibid., 73.

- [10] Ibid., 47.

- [11] Rupert Sargent Holland, ed., Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1912), 21.

- [12] Edward Philbrick to Edward Atkinson May 25, 1862, in Elizabeth Ware Pearson, ed. Letters from Port Royal Written at the Time of the Civil War (Boston, MA: W. B. Clarke Company, 1906), 56; James A. Porter, Modern Negro Art (The American Negro, His History and Literature) (New York: Arno Press, 1969), 56.

- [13] See Susan-Mary Grant, North over South: Northern Nationalism and American Identity in the Antebellum Era (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000).

- [14] [William C. Gannett and E. E. Hale] "Education of the Freedmen," The North American Review 101, no. 209 (October 1865): 533. The author(s) of this article, as well as “The Freedmen at Port Royal,” The North American Review 101, no. 208(July 1865), is unknown, but John R. Rachel indicates that it is co-written by Gannett and Hale. Therefore, this essay will also attribute authorship to Gannett and Hale. See John R. Rachal, “Gideonites and Freedmen: Adult Literacy Education at Port Royal, 1862-1865,” The Journal of Negro Education 55, no. 4 (1986): 453-469.

- [15] John R. Rachal, “Gideonites and Freedmen: Adult Literacy Education at Port Royal, 1862-1865,” The Journal of Negro Education 55, no. 4 (1986): 463–4.

- [16] [William C. Gannett and E. E. Hale] “The Freedmen at Port Royal,” The North American Review 101, no. 208 (July 1865), 4.

- [17] Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, 189.

- [18] Ibid., 188–94.

- [19] Williamson, After Slavery, 4–5.

- [20] Ibid., 55–56.

- [21] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 44, p. 75, 159.

- [22] Eric Foner, Reconstruction, 1863-1877: America’s Unfinished Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 70–71.

- [23] Williamson, After Slavery, 59–62.

- [24] Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction, 389.

If you can read only one book:

Rose, Willie Lee. Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Books:

Burton, Orville Vernon, Wilbur Cross, and Emory Campbell. Penn Center: A History Preserved. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014.

Dougherty, Kevin. The Port Royal Experiment: A Case Study in Development. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction, 1863-1877: America’s Unfinished Revolution. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Gannett, William C. and E. E. Hale. “The Freedmen at Port Royal,” The North American Review 101, no. 208 (July 1865): 1-28.

———. "Education of the Freedmen," The North American Review 101, no. 209 (October 1865): 528-550.

Holland, Rupert Sargent, ed. Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne, Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-1884. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1912.

Oakes, James. Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

Ochiai, Akiko. “The Port Royal Experiment Revisited: Northern Visions of Reconstruction and the Land Question.” The New England Quarterly 74, no. 1 (2001): 94–117.

Pearson, Elizabeth Ware ed. Letters from Port Royal Written at the Time of the Civil War. Boston: W. B. Clarke Company, 1906.

Rachal, John R. “Gideonites and Freedmen: Adult Literacy Education at Port Royal, 1862-1865.” The Journal of Negro Education 55, no. 4 (1986): 453–69.

United States. Department of the Treasury and Edward Lillie Pierce. The Freedmen of Port Royal, South-Carolina. Official Reports of Edward L. Pierce. New York: Rebellion Record, 1863.

Williamson, Joel. After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861-1877 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1965).

Organizations:

Penn Center

Penn Center is the site of a former school of the Port Royal Experiment and a heritage center for the Sea Islands.

Web Resources:

The Civil War Women’s Port Royal experiment is a brief summary of the Port Royal Experiment.

The Port Royal Experiment is a brief documentary produced by A. J. Koelker.

Other Sources:

Voices of the Civil War Episode 9: “Port Royal Experiment

This is a short YouTube video on the Port Royal Experiment.