The Rebel Yell: The Seething Blast of an Imaginary Hell

by Richard G. Williams, Jr.

To truly understand the Rebel Yell one has to listen to it. See the resources section for how to do so. Rebel Yell | Seething Blast of an Imaginary Hell | Rebel Yell Bourbon | The Particular Corkscrew Sensation that it Sends Down Your Backbone | Pibroch of Southern Fealty | Ghoulish Shriek of Death | Sweet Song of Victory | First Manassas | Stonewall Jackson | Cherokees | Penetrating Rasping Shrieking Blood-curdling Noise.

“Then arose that do-or-die expression, that maniacal maelstrom of sound; that penetrating, rasping, shrieking, blood-curdling noise that could be heard for miles and whose volume reached the heavens—such an expression as never yet came from the throats of sane men, but from men whom the seething blast of an imaginary hell would not check while the sound lasted.”—Confederate Colonel Keller Anderson of Kentucky's Orphan Brigade. [1]

There are few aspects of the Civil War which have been engrained in American culture and remembrance more than the Confederate soldiers’ Rebel Yell. Of course, Confederate symbolism and its collective impact on culture are not confined to the Rebel Yell. Historian Craig A. Warren makes this point in his recent book, The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History:

“Almost 150 years after Appomattox, the symbols of the Southern Confederacy continue to play a powerful and divisive role within American society. From street corners to the halls of Congress, Americans contend with Confederate imagery that holds widely divergent meaning for people of different racial, regional, and ideological backgrounds.” [2]

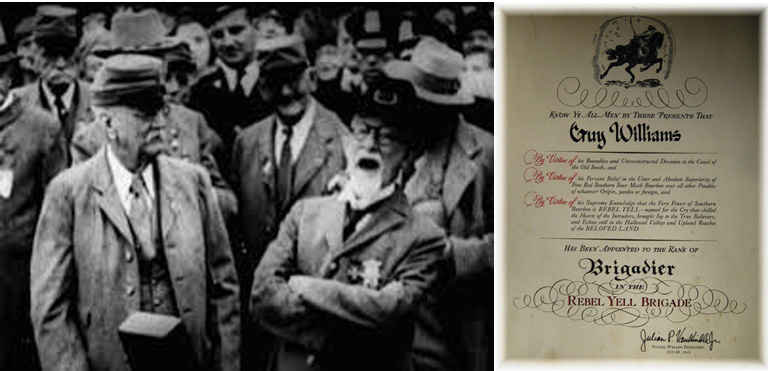

But these symbols, despite their “divisive role”, have come to transcend many of these racial, regional and ideological backgrounds. As Warren notes: “Like the six-gun and cowboy hat of the Old West, the battle flag has transcended its regional and national origins.” The same can be said of the Rebel Yell. From whiskey to clothing to music and film, the bone-chilling scream of the Confederate soldier has become a legendary and an iconic symbol of the Southern spirit symbolizing fearlessness, rebellion, and the Southern warrior ethos. This ethos was romantically recalled (and capitalized upon) by the Kentucky distillery, Stitzel-Weller, and their Rebel Yell brand in a “commission” issued to their customers appointing them as a “Brigadier” in the “Rebel Yell Brigade” in the 1960’s:

“. . . the Very Finest of Southern Bourbon is REBEL YELL—named for the Cry that chilled the Hearts of the Intruders, brought Joy to the True Believers, and Echoes still in the Hallowed Valleys and Upland Reaches of the BELOVED LAND.” [3]

While that description would be aptly characterized as romanticized, it is exact in at least one sense: the sound most assuredly “chilled the hearts of intruders.” Its effect on the Union army could be described as nightmarish, as historian Robert K. Krick notes the Yankee response upon hearing the other-worldly screams at the Battle of Chancellorsville:

“A French volunteer at Hooker's headquarters spotted the Eleventh Corps fugitives in ‘close-packed ranks rushing like legions of the damned ’toward him. The Rebel yell unmanned the foreigner, who reported that ‘all of the [Confederates] roar like beasts. ’” [4]

Another Ohio soldier present at the Battle of Chancellorsville would later recall:

“At last the storm signal reached us. From away to our rear and close at hand upon our right came the ‘Rebel yell.’ Comrades of the Fifty-Fifth have all heard that shrill note and know how it stirs the blood and calls out all the impulses of resistance. The men on the right brigade now began to come back in panic.” [5]

And one 9th Indiana soldier described the Rebel Yell as “the ugliest sound that any mortal ever heard—even a mortal exhausted and unnerved by two days of hard fighting, without sleep, without rest, and without hope.” [6]

Author Craig Warren further notes that soldiers from a Wisconsin unit were quoted in 1909 about their memories of the unearthly Rebel Yell: “And that yell. There is nothing like it this side of the infernal region and the peculiar corkscrew sensation that it sends down your backbone under these circumstances can never be told.” [7]

The yell’s ability to bring dread and fear upon Union soldiers is well-documented. But the psychological impact of the scream was, predictably, quite the opposite on Confederate soldiers. Douglas Southall Freeman, who once referred to the Rebel Yell as “the Pibroch of Southern Fealty”, describes how Confederates often reacted to their “Pibroch”:

“Confident and rejoicing, they raised the rebel yell in Anderson's corps and took it up along the whole line. At a given point, one could hear it on the right, then in front and then dying away in the distance on the left. ’Again the shout arose on the right — again it rushed down upon us from a distance of perhaps two miles, ‘ one officer wrote, ‘— again we caught it and flung it joyously to the left, where it ceased only when the last post had huzzahed. The effect was beyond expression. It seemed to fill every heart with new life, to inspire every nerve with might never known before. Men seemed fairly convulsed with the fierce enthusiasm; and I believe that if at that instant the advance of the whole army upon Grant could have been ordered, we should have swept [him] into the very Rappahannock.’” [8]

Apparently, what was a ghoulish shriek of death to the Union army was a sweet song of victory and joy to the Confederate army.

Though referred to in countless diaries, letters and histories of the Civil War, there have been only three book length examinations of this “ugliest sound.” The first one, published in 1954, was written by H. Allen Smith and is titled: The Rebel Yell: Being a Carpetbagger's Attempt to Establish the Truth Concerning the Screech of the Confederate Soldier Plus Lesser Matters Appertaining to the Peculiar Habits of the South. Obviously, as one can tell from the title, Smith’s book was a humorous, tongue in cheek look at the Rebel Yell. The other two books looking at the Rebel Yell were published very recently. The first one was written by Terry W. Elliott and published by Pelican Publishing Company in 2013. It is titled, The History of the Rebel Yell. This book is concise but contains a wealth of information and is written in a popular style and intended for a general audience. It’s a good starting point for those interested in the topic. The most recent book has already been mentioned. The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History was published in 2014 and authored by Associate Professor of English at Penn State, Dr. Craig A. Warren. Warren’s takes a serious and scholarly approach to the history of the Rebel Yell. [9]

There is some debate as to the origination of, and inspiration for, the Rebel Yell. A number of writers and researchers have suggested the yell traces its roots to the “war cry of the Gael”—the battle cry of the Scottish Highlanders. The fact that many of the soldiers in the Confederate army were descended from the Scots-Irish makes this a plausible theory. Yet others have attributed it, at least in part, to the war cry of the Native Americans—most notably the Cherokee tribe. Craig Warren spends some time in his book on the Rebel Yell discussing an editorial which first appeared in the St. Louis Republic in February of 1889 and later in many reprints throughout much of the South and Midwest. The author of the editorial claims that the cry, which became known as the Rebel Yell, had existed in American military history for at least a quarter century prior to 1861 and had its genesis with Native-Americans. In discussing this widely read and influential editorial, Warren further notes:

“The author went on to stress two points about the career of the Rebel Yell prior to the Civil War. First, the scream had never fallen silent since its adoption by white southern patriots in the late eighteenth century. After serving the cause of the rebels during the revolution, it aided freedom-loving stalwarts during numerous conflicts from Tennessee to Texas: ‘It was raised by rebels at King’s Mountain . . .’” [10]

Indeed, as patriot militia from Tennessee charged up the hill at the Battle of King’s Mountain, Tory commander Abraham DePeyster warned a superior, “These things are ominous—these are the damned yelling boys.”[11]

Warren also quotes one historian who went so far as to suggest that the resemblances between the Rebel Yell and the war cry of the Cherokee evolved due to similar existences between the Native Americans and rural Southerners, “[the] degree of acculturation was such that the life-style of the Cherokee closely paralleled that of southern whites.”[12]

Those parallels would include close contact and familiarity with the sounds of both wild and domesticated animals. Some of those animalistic, guttural noises have been used by Civil War soldiers to describe the Rebel Yell. Rural life in the South included becoming familiar with various animal sounds for a variety of reasons: everything from turkey calling, to hog calling, to the call of the fox hunter—all were part of daily life for rural Southerners. As Terry Elliott quotes one Mississippian in his book on the Rebel Yell:

“Hunting Fox, ‘coons, ‘Possums, rabbits etc. Has been all but universal in the south, and even yet is common. Formerly ALL was rural. A FEW kept a pack of dogs, but every one had one or more hounds. Once the dog or dogs were on the track, yelling to them was inevitable. I have heard and given this YELL since a mere lad. The so-called ‘rebel yell’ was only the hunter’s yell, MERGED into the army.” [13]

Elliott further illustrates these parallels between Cherokee Indians and rural Southern whites with the fact that some Cherokee Confederate units adopted animal noises as their Rebel Yell:

“Each time he fired a shot Cherokee Bill would loudly gobble like a turkey. The ‘gobbling’ sound was an odd mixture of several noises; most seemed to think it was like the howl of a coyote combined with the gobble of a turkey. At any rate, it was a blood chilling scream that in the Indian world ‘signified death to anyone who heard it.’—Back in the Civil War, when many Territory Indians fought for the Confederacy, they apparently used this gobble as their version of the ‘Rebel Yell.’” [14]

Of course, there is also the popular notion that the Rebel Yell was birthed at First Manassas, as Dr. James I. Robertson, Jr. writes in his definitive biography of Stonewall Jackson:

“Now the men could charge the enemy and, in Jackson’s words, ‘yell like furies!’ They did both, and at that moment the world heard for the first time the scream of what became known as the ‘Rebel Yell.’”[15]

This theory became even more engrained in the mythology surrounding Jackson after Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville, as Confederate soldiers would intermingle the rallying cry of “Remember Jackson!” with their Rebel Yell.

Numerous other writers and historians have also claimed First Manassas as the birthday of the Rebel Yell, including Shelby Foote (The Civil War: A Narrative) and Tony Horwitz (Confederates in the Attic).[16]

Certainly, all of these theories have some validity, including the assertion that the Confederate version of the Rebel Yell was first heard at the Battle of First Manassas. But, as Craig Warren points out, “. . . the Rebel Yell had no clear parentage.” [17]

In recent years, perhaps due to the Civil War’s sesquicentennial commemoration, there has been a renewed interest in the Rebel Yell evidenced, in part, by both Warren’s and Elliott’s books. Sources as diverse as National Public Radio and the Museum of the Confederacy have featured interviews and discussions on the topic. And the Museum of the Confederacy, along with the Smithsonian Institute, has archived video and audio recordings of Confederate Veterans demonstrating their versions of the Rebel Yell. The Museum of the Confederacy has also used computer enhancement to produce a DVD of what the Rebel Yell would have sounded like in regimental and larger groups, based on these original recordings.

Certainly, this “penetrating, rasping, shrieking, blood-curdling noise” that once echoed across America’s smoke-covered battlefields has become synonymous with that of America’s greatest struggle. But it has become so much more, as both Terry Elliott and Craig Warren conclude in their respective studies:

“It’s possible that the power of the Rebel Yell has been embellished through the decades, first by veterans and later by others, as it made its way from memory to legend.”

“The Rebel Yell has gone down in Civil War Memory as a ferocious and unnerving battle cry. . . . there remains good reason to study the scream as experienced by the men fighting for or against the Confederacy. But what the Rebel Yell contributed to U.S. history after 1865, in both volume and range, rivals anything it wrought on the Civil War Battlefield.” [18]If that legend endures, the volume and range will still be heard yet again at the Civil War’s bicentennial.

- [1] Keller Anderson, “The Rebel Yell,” in Confederate Veteran Magazine, 13, no. 11 (November 1905): 501.

- [2] Craig A. Warren, The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press,, 2014), xi.

- [3] Ibid; Rebel Yell Colonel’s Appointment document, issued by the Stitzel-Weller distillery, circa 1966, author’s collection.

- [4] Robert K. Krick, , “Like Chaff Before the Wind: Stonewall Jackson's Mighty Flank Attack at Chancellorsville” Civil War Trust, http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/chancellorsville/chancellorsville-history-articles/flankattackkrick.html, accessed March 19,2014.

- [5] Hartwell Osborn, Trials and Triumphs—The Record of the Fifty-Fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1904), 71.

- [6] Edward B. Williams, Hood’s Texas Brigade in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 183.

- [7] Craig A. Warren, Rebel Yell, 21.

- [8] A pibroch is a form of music used with Scottish bagpipes; Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee (New York & London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 303.

- [9]H. Allen Smith, The Rebel Yell: Being a Carpetbagger's Attempt to Establish the Truth Concerning the Screech of the Confederate Soldier Plus Lesser Matters Appertaining to the Peculiar Habits of the South (New York: Doubleday, 1954); Terry W. Elliott(The History of the Rebel Yell (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2013).

- [10] Craig A. Warren, Rebel Yell, 40.

- [11] J. David Dameron, King’s Mountain: The Defeat of the Loyalists, October 7, 1780 (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003), 81.

- [12] Craig A. Warren, Rebel Yell, 41.

- [13] Terry W. Elliott, History of the Rebel Yell, 44.

- [14] Ibid., 49.

- [15] James I. Robertson, Jr., Stonewall Jackson—The Man, The Soldier, The Legend (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1997), 266.

- [16] Shelby Foote, The Civil War. A Narrative, 3 vols. (New York: Random House 1958-63-74); Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York/Toronto: Pantheon Books Random House, 1998).

- [17] Craig A. Warren, Rebel Yell, 66.

- [18] Terry W. Elliott, History of the Rebel Yell, 138-139; Craig A. Warren, Rebel Yell, 162.

If you can read only one book:

Warren, Craig A. The Rebel Yell: A Cultural History. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2014.

Books:

Elliott, Terry W. The History of the Rebel Yell. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2013.

Smith, Allen H. The Rebel Yell: Being a Carpetbagger's Attempt to Establish the Truth Concerning the Screech of the Confederate Soldier Plus Lesser Matters Appertaining to the Peculiar Habits of the South. New York: Doubleday, 1954.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This is a Library of Congress recording of various Confederate veterans demonstrating the Rebel Yell, circa 1930s.

This is a brief recording of a Rebel Yell from a veterans’ reunion at Gettysburg.

The 26th North Carolina Regiment website includes recordings and an interview with Confederate veteran Pvt. Thomas N. Alexander of the 37th North Carolina in which he demonstrates the Rebel Yell. This is the recording used by the Museum of the Confederacy to reproduce the Rebel Yell.

This is the recording in the possession of the United Daughters of the Confederacy of SS Simmons of the 8th Virginia Cavalry, recorded in 1934 when he was 93 years old. This recording was used by the Museum of the Confederacy to validate the authenticity of Thomas Alexander’s recording.

This is the Museum of the Confederacy’s The Rebel Yell Lives Part 1 Rediscovering History.

This is the Museum of the Confederacy’s The Rebel Yell Lives Part 2 – The Re-enactors.

This YouTube video includes part of the Museum of the Confederacy’s reproduction of the Rebel Yell and footage of re-enactors emulating it.

Other Sources:

The Rebel Yell Lives CD

The Rebel Yell Lives is a CD produced by the Museum of the Confederacy which can be purchased for $15 at the Museum or on line.