The Republican Party to 1865

by Timothy Mason Roberts

The story of the Republican Party's transformation in its early years shows how a powerful federal government first gained legitimacy in American opinion as an agent for liberal change.

There are several paradoxes about the founding and early years of the Republican Party, from 1854 to 1865. It is the only political party in American history to achieve national power despite having no support in a large section of the country. With origins in the Christian evangelical moral crusade of the Second Great Awakening, during the Civil War in abolishing slavery it became an engine of vast political liberation and social destruction. Some Republicans despised slavery and wanted it abolished as a national sin, but others despised black people, and wanted slavery regulated to preserve white people’s opportunity for ‘free labor.’ A rural movement in the agricultural Old Northwest, it quickly came to control the federal government, and, a decade after its emergence, was poised to vastly expand the central government’s size and power. Most of this happened, of course, because soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln, only the Republicans’ second candidate for the White House, the war broke out, and would continue his entire first administration and the beginning of his second. This essay traces the development of the Republican Party through the end of the Civil War. The story of its transformation shows how a powerful federal government first gained legitimacy in American opinion as an agent for liberal reform.

Background in the Early American Republic

Although the Republican Party emerged only in the 1850s, its origins may be traced to two events that happened a generation earlier. First, the Second Great Awakening, what historians term the explosion of emotional religion and popular religious organizations, spread across the United States beginning in the 1820s. Preachers of the era called all Americans – rich, poor, free, slave, men and women – to repent, or choose a new life direction by professing faith in Jesus as the Christ, and following his teaching. Different from the Great Awakening of the colonial period, the Second Great Awakening was marked by establishment of new churches and voluntary associations, not simply a revival of interest and affiliation with traditional faiths. Several Protestant churches grew from small sects to flourishing national movements – Baptists, Presbyterians, and especially Methodists, which succeeded not only because of their message of God’s mercy and love, not judgment, for anyone, but also because of their ability to organize a network of itinerant preachers, church periodicals, and money-raising institutions. Like the Democratic political party, established around the same time, these new American churches learned how to organize people across regions and causes.

Alongside churches per se, the Second Great Awakening also spawned para-church organizations, what Alexis de Tocqueville called “voluntary associations.”[1] In the absence of a large welfare state that we have today, services for the poor and the marginalized in the early republic fell to private initiative. Second Great Awakening theology, meanwhile, called for the ‘perfection’ of society as a necessary precondition for Christ’s return to earth. These two forces spawned a host of reform movements, seeking to solve social problems both in the United States and overseas. The largest movement was the American Temperance Society, which discouraged consumption of alcohol. The most global enterprise was the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which sent missionaries to the American frontier and around the world. The most controversial organization was the American Anti-slavery Society, founded in 1831 by William Lloyd Garrison, who, inspired by the preaching of the evangelist Charles Finney, dedicated his life to abolishing slavery. Abolitionism was a fringe movement until the mid-1850s, but like other voluntary groups and the new churches, it sought to develop the infrastructure and inspiration for armies of ordinary people committed to its cause.

The other important development that later provided a framework for the Republican Party was the land reform movement of the 1830s. This followed the Panic of 1837, when land prices, driven to unsustainable levels by speculation, suddenly collapsed. Working men’s advocates launched a drive to persuade Congress to fix prices of land in the public domain that the government was offering for sale, or, more radically, to give it away for free. George Evans, an English immigrant, began publishing literature in the 1840s calling ordinary Americans to “vote yourself a farm,” meaning supporting politicians committed to western land reform.[2] Evans believed that land ownership was a fundamental human right. Congress would debate the homestead question for decades. Originally the cause had support from liberal politicians in the North and South, but by mid-century most southerners opposed land reform because it would attract antislavery migrants to the West.

The Demise of the Second Party System

These different strands of moral reform became woven politically beginning in 1848. That year saw treaty negotiations completed to end the U.S. war with Mexico, which vastly increased American territory, gaining land that would eventually be part of seven states, not including Texas, formerly Mexican, whose U.S. annexation in 1845 had partly provoked the war. In the presidential election in 1848 abolitionists, working men interested in restricting slavery’s westward expansion, and northern Democrats dissatisfied with southerners’ increasing influence in the party launched a third party, the Free Soil Party. Free Soilers basically had a single issue, which was to pass federal legislation prohibiting slavery in U.S. territories—at the time, only radical abolitionists sought to end slavery in the southern states themselves. The Free Soil candidate for president, Martin Van Buren, did not win any state, but, in gaining support in a few key states including Ohio and New York, likely helped ensure the victory of the Whig Zachary Taylor. Taylor’s presidency is obscure, but at the time it created tension, as he pledged not to oppose any legislation passed by Congress, including a ‘free soil’ bill. This Washington reticence surprised southerners, who assumed Taylor, a military hero and Louisiana slave owner, would defend their interests. While defeated in 1848, Free Soilers provided a kind of blue print for the Republicans’ formation: appealing to a coalition of northern voters to advocate for federal laws protecting opportunities for working men to achieve economic independence through access to land. Free Soil campaign literature also summoned working men of the world to come to the United States to support their cause, an international theme that also would resonate later in the Republican Party’s platform.

In response to real debates in Congress for the first time about the legal and economic fate of the American West—open or closed to slave labor—proslavery southerners launched a blistering campaign to ensure the South was not denied access to the Mexican War’s spoils and to rein in a federal government hosting dangerous debates about antislavery reform. Led by old Kentucky Senator Henry Clay and, upon his death, his successor Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Congress was thus presented with an ‘omnibus’ series of bills, which, when passed, became known as the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise allowed California to enter the Union as a state prohibiting slavery, directed new territories to allow their own residents to decide whether slavery would be allowed, under what became known as ‘popular sovereignty,’ called for ending the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and, most controversially, enacted a new Fugitive Slave Law, requiring federal marshals to help slave owners catch runaway slaves hiding in northern states, where slavery had been outlawed. Very few fugitive slaves were brought back to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Law. Its real impact was northerners’ outcry: by 1830 slavery had been abolished across the North by state laws and the Missouri Compromise of 1820, but now slavery’s oppressiveness seemed to have returned to their neighborhoods. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling Uncle Tom’s Cabin dramatized the plight of slaves and excoriated complacent white people in the North for not taking a stand. Stowe’s book, rekindling messages of Christian philanthropy and humanitarian organization first prescribed in the Second Great Awakening, became the moral manifesto of the Republican Party, as the Free Soil platform did for its political strategy. President Lincoln is alleged to have declared to Stowe in 1862, “So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!”[3]

While popular sovereignty in New Mexico and Utah was hardly the central controversy of the Compromise of 1850, its adoption in the territories of Nebraska and Kansas proved explosive. Seeing to organize these areas for statehood, Douglas persuaded Congress and President Franklin Pierce to adopt the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, by which slavery would or would not enter Kansas and Nebraska depending on popular ratification meetings each territorial government was to organize. Most controversially, the Kansas-Nebraska Act seemed to overturn the Missouri Compromise, a law antislavery northerners had assumed would protect them perpetually, if not from slave catchers, from slavery itself. Tilting to slave interests, the Act denied noncitizen immigrants the right to vote or hold office in either territory. Kansas would see scenes of civil war by 1856, as proslavery and antislavery settlers scrambled to stake claims and intimidate or even murder any settlers wishing to press competing interests.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was a kind of final straw for moderate antislavery northerners who previously had been unwilling to join the Free Soil cause, and remained content within the Democratic or Whig parties. The Act substantively reorganized the American political system, from a national system, in which Democrats and Whigs had representation throughout the country, to a sectional system, in which the Democratic Party, as a means of survival, was increasingly dominated by interests of the South. The Whig party, established by Clay in opposition to the populist policies of President Andrew Jackson, attempted to survive by avoiding the slavery issue, calling in its 1852 campaign platform for support of the Fugitive Slave Law, but also “deprecate[ion of] all further agitation of the question thus settled as dangerous to our peace.”[4] In the context of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, northern voters would interpret that reticence as abdication of responsibility.

Amid the seismic impact of the Kansas-Nebraska Act an ephemeral party, the American or ‘Know Nothing’ movement, emerged in the mid-1850s. Enjoying success especially at the state and local levels, Know Nothings, nicknamed because of their alleged code words upon being queried about their politics, ‘I know nothing,’ were xenophobes, reacting against millions of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and the German states that arrived in the United States after famines and political upheavals in Europe during the 1840s. The American party, like the Whig party, did not directly address slavery. Instead it focused on restriction of immigrant rights to vote, hold office, and become citizens. In 1856 the Know Nothings both crested and began to decline; generally speaking, the Democratic Party was happy to court Irish working men lured by race-based economic and political opportunities, and the Republican Party adroitly began to recruit Germans who associated Southern slave owners and their political power with old German aristocracy.

Thus many northerners were politically active in 1854, though not to vote for the parties in existence up to then. Many were caucusing in so-called anti-Nebraska meetings, which would produce another new, but more durable, political movement. The Kansas-Nebraska Act took effect on May 30, but even before this, on February 28, a few dozen of its opponents met in Ripon, Wisconsin to call for the organization of a new party, using the name, Republicans, to invoke the American War of Independence. Horace Greeley, editor of the most widely read newspaper of the day, the New York Tribune, circulated the new party’s name. Like the Wisconsin organizers, Greeley argued that supporters of the new party were not radical, but embraced traditional American revolutionary values. They sought “to restore the Union to its true mission of champion and promulgator of Liberty rather than propagandist of slavery.[5] On July 6 Michigan held the party’s first state convention; other northern states followed. Congressional elections in 1854-56 confirmed the meteoric rise of Republican strength, especially at the national level. Where none of the thirty-one states had Republican governors at the beginning of 1854, there were eleven by the end of 1857. The 33rd Congress’s House of Representatives in 1854 consisted of 157 Democrats, 71 Whigs, four Free Soilers, and two Independents. Two years later the 35th Congress’s House of Representatives consisted of 132 Democrats, 90 Republicans, 14 Americans, and one Independent.[6] Responding to economic anxiety with evangelical fervor and grass-roots organizational skill, Republican organizers appealed to younger men in the North frustrated by the status quo. In this regard they were not so different from the demographic makeup of Progressives at the turn of the twentieth century or the New Left of the 1960s.

The 1856 and 1860 Presidential Elections

Republicans nominated John C. Frémont, a Mexican War hero and former antislavery senator from the new state of California, for president in 1856, espousing a motto of “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Speech, Free Men.”[7] Most voters considered Frémont an antislavery crusader, and indeed three months into the Civil War, while a major general and Commander of the Department of the West he presumed to decree that all property of rebels in the state of Missouri would be confiscated, including slaves, and that all slaves would be set free. This provoked President Abraham Lincoln to remove him from command. Democrats easily won the 1856 election by warning voters that any federal antislavery laws would likely provoke civil war, and deprecating the anti-immigrant platform of the American Party. On the other hand, the American Party gained 800,000 votes, 300,000 more than the difference between the respective Democratic and Republican totals—a recipe, along with the splintering of the Democratic Party into three factions, for Republican victory four years later.

With one important change, the Republican Party’s platforms in 1856 and 1860 were greatly similar. In both elections, Republicans advocated the principle that the federal government should not defer to state and local governments to shape the country’s laws and economy (by the early twenty-first century the Republican Party had reversed its philosophy on these issues). In both elections Republicans called for Congress to prohibit slavery in U.S. territories, and to provide funding for a transcontinental railroad and river and harbor improvements. The idea of an active federal government was new at the time; previously, state and territorial governments dictated laws about slavery, for or against, and provided funding for the country’s infrastructure development. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law provided for federal authority only in the breach, since it pertained only to slaves escaping across state lines, and, in any case, never resulted in more than a few individuals being returned to bondage. In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Dred Scot v. Sanford that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 violated the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, because it denied slave owners’ rights to hold slave property anywhere north of Missouri’s southern boundary. Hardly resolving the slavery crisis, this ruling helped solidify Republican support. It confirmed many northerners’ suspicions that there was a conspiracy in the federal government beholden to the ‘slave power,’ soluble only by an overwhelming turnout of antislavery support in the 1860 election.

An important difference between the Republican platforms in 1856 and 1860 was elements in the latter election designed to appeal to voters on the margins of the electorate. Specifically, in 1856 Republicans had called for a federal ban on polygamy as, along with slavery, a “relic of barbarism,” and, meanwhile, made no mention of land reform.[8] However, in 1860 Republicans made no mention of polygamy, and called for federal action on a homestead bill, providing cheap public land to any interested person, native-born or immigrant. The association of polygamy, the practice of plural marriage among Mormons in the territory of Utah, with slavery was part a calculation to force southerners, in condemning the Republican platform, to seem for polygamy. Nonetheless, the condemnation echoed Republicans’ roots in the early republic’s moral crusades. On the other hand, the 1860 platform’s silence about polygamy and addition of a citizenship-blind homestead law showed the Republicans’ wooing of religious liberals and immigrants, erstwhile Democratic Party supporters.

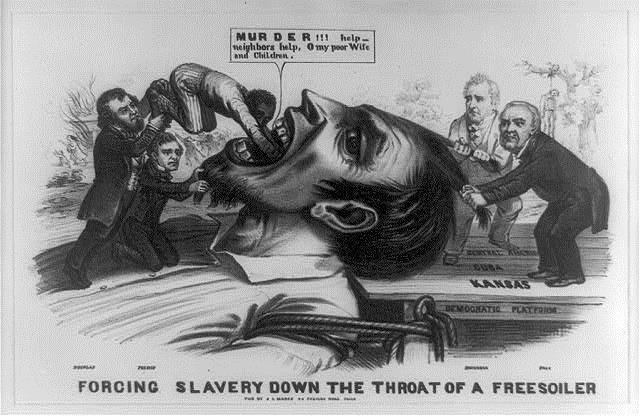

While by 1860 Republicans were the party of individual economic opportunity and ethnic diversity, they firmly rejected radical abolitionism’s arguments for racial equality and an end to slavery in the South. A famous 1856 political cartoon showed President James Buchanan and Senator Stephen Douglas shoving a black man, representing slavery, down the throat of a Free Soiler, represented as a white man. Such a representation was hardly an attack on slavery on the basis of its inhumanity. In his famous debates with Douglas in 1858, Abraham Lincoln had condemned slavery for denying slaves the “fruits of their own labor.”[9] But on the occasion Lincoln also affirmed his belief in black social and racial inequality. In his 1861 presidential inaugural he denied any power to affect slavery where it already existed. Different from his predecessor Frémont, Lincoln was an antislavery moderate. But his election triggered the secession crisis anyway.

Wartime Politics and a Yankee Leviathan

The Civil War did not so much change the Republican Party’s policies as hasten their fulfillment and carry them to extreme ends. Before the war Republicans opposed slavery and supported stronger federal government and western settlement. The war, albeit amid vast devastation, provided the opportunity for these goals’ accomplishment. With southerners’ exodus from Congress, Republicans dominated the national legislature throughout the war, easily passing important legislation that had stalled in the antebellum era. The Homestead Act of 1862 offered small lots of land for fixed prices in the western territories to anyone legally settling on and improving the lot for five years. The Morrill Act designated land in each state for public higher education in engineering and the mechanical arts, agriculture, and military science. With these Republican measures, the federal government vastly extended its authority westward.

Neither of these measures was controversial, but steps towards eventual abolition of slavery were different, because of division in the Republican Party, and indeed the North as a whole, over whether the secession crisis would be more quickly resolved by maintaining slavery, or hastening its end. President Lincoln rejected Frémont’s emancipation in Missouri, but, under pressure from runaway slaves and Greeley, Garrison, and the famous former slave Frederick Douglass, both Congress and certain Republican generals took intermittent steps towards abolition. The Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862 sanctioned the taking of slaves being used in support of the rebellion. In an August 1862 editorial Greeley called upon Lincoln publicly to abolish slavery. Lincoln, earlier opposing the Confiscation Acts over fears they would push the ‘border states’ into secession, demurred. But on January 1, 1863 he dramatically declared the abolition of slavery in all areas of the rebellious South—though confirming the extenuating conditions the war presented, he rationalized the Emancipation Proclamation as a “fit and necessary measure for suppressing said Rebellion.”[10] Some have interpreted this statement as evidence of Lincoln’s expediency and lack of antislavery conviction. More importantly, it shows how much the war accelerated Republicans’ fulfillment of their long-term goals. Aided by timely Union military victories in late 1864, Lincoln won a hard earned re-election to the presidency—a whopping 45% of American voters (remembering that most southerners were disenfranchised) voted for the former Union general George McClellan, the candidate of the Democratic Party, whose platform called for an immediate cessation of hostilities and negotiations with the South.[11] Lincoln’s re-election validated the Republicans’ centralization of authority, including the transformation of the war from a conflict over restoring the Union to a conflict that also included ending slavery through the use of federal power.

Meanwhile, although Republicans had long called for a stronger federal government, none could have anticipated Lincoln’s power as a wartime president, or the government’s wartime growth. In pursuit of saving the Union, Lincoln not only declared the immediate abolition of slavery where it had always existed, he also declared martial law in the North, arresting thousands of antiwar dissenters, and early in the war spent considerable federal monies without Congressional authorization. Meanwhile federal spending increased twenty-five fold by 1865, when the U.S. government for the first time in history spent a billion dollars a year. Government wartime spending indeed provided the lift-off for the American industrial age. Federal power would retreat after the war, and in the post-World War II era the Republican Party would embrace an ideology more skeptical of central government domestic spending. But the Republican Party during the Civil War introduced the idea in American history that the federal government has an important role to enforce the country’s moral and economic welfare.

- [1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed., Isaac Kramnick (New York: Penguin, 2003), xxx.

-

[2] David Brion Davis, ed., Antebellum American Culture: An Interpretive Anthology, (State College: Penn State University Press, 1979), 135-6.

-

[3] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852); Daniel Vollaro, “Lincoln, Stowe, and the ‘Little Woman/Great War’ Story: The Making, and Breaking, of a Great American Anecdote,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 30 (2009):18-34, esp. 22.

- [4] "Whig Party Platform of 1852,” American Presidency Project, at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=25856, accessed April 25, 2014.

- [5] New-York Tribune, June 24, 1854. Emphasis added.

- [6] Kenneth Martis, Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress (New York: Macmillan , 1989).

-

[7] Horace Greeley, Proceedings of the First Three Republican National Conventions of 1856, 1860 and 1864 (New York: C. W. Johnson, 1893), 78.

- [8] "Republican Party Platform of 1856,” American Presidency Project, at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29619, accessed April 25, 2014.

- [9] Abraham Lincoln, “Speech at Carlinville, Illinois, August 31, 1858,” in Abraham Lincoln Association, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy Basler, at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln3/1:7.1?rgn=div2;view=fulltext, accessed April 25, 2014.

- [10] Abraham Lincoln, Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863, at United States National Archives, “America’s Historical Documents,” at http://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/document.html?doc=8&title.raw=Emancipation%20Proclamation, accessed April 25, 2014.

- [11] University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab, “Voting America: Presidential Election, 1864,” at http://dsl.richmond.edu/voting/indelections.php?year=1864, accessed January 9, 2014.

If you can read only one book:

Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: From Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: WW Norton, 2005, Chaps 6-25.

Books:

Anbinder, Tyler G. Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Bensel, Richard. Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859-1877. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

———. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: WW Norton, 2010.

Gienapp, William. Grand Old Party: A History of the Republicans. New York: Random House, 2003.

Holt, Michael. The Political Crisis of the 1850s. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 1978.

Lause, Mark. Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Levine, Bruce S. The Spirit of 1848 German Immigrants Labor Conflict and the Coming of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Neely, Mark E. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies during the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Organizations:

The Republican Party

It includes a brief history of the party as well as current information.

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Founded in 1994 by Richard Gilder and Lewis E. Lehrman, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization devoted to the improvement of history education. The Institute has developed an array of programs for schools, teachers, and students that now operate in all fifty states, including a website that features more than 60,000 unique historical documents of early American history in the Gilder Lehrman Collection.

Filson Historical Society

The Filson Historical Society is Kentucky’s oldest privately supported Historical Society, founded in 1884. Their collections include Civil War history materials as well as materials relating to the Kentucky and the Ohio Valley.

Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College

The Civil War Institute engages with Gettysburg College students, general audiences, graduate students, and scholars in a dialogue about Civil War history through an interdisciplinary approach dedicated to public interpretation, historic preservation, public policy, teaching, and academic research.

Abraham Lincoln Association

The mission of the Association is to observe each anniversary of the birth of Abraham Lincoln; to preserve and make more readily accessible the landmarks associated with his life; and to actively encourage, promote and aid the collection and dissemination of authentic information regarding all phases of his life and career.

Web Resources:

An international consortium of scholars and teachers, H-Net Humanities and Social Sciences Online creates and coordinates internet networks with the common objective of advancing teaching and research in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. One of their discussion networks is h-civwar which covers Civil War history.

The American Presidency Project was established in 1999 to collect primary source documents relating to the study of the presidency and make them available to the public.

This discussion network of H-Net focuses on the history of the early American republic, pre-Civil War.

This discussion network of H-Net focuses on American political history.

Voting America United States Politics 1840-2008 examines long-term patterns in presidential election politics in the United States from the 1840s to today as well as some patterns in recent congressional election politics. The project offers a wide spectrum of animated and interactive visualizations of how Americans voted in elections over the past 168 years as well as expert analysis and commentary videos that discuss some of the most interesting and significant trends in American political history.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.