The Sand Creek Massacre

by Ari Kelman

On November 29, 1864, approximately 700 federal troops, commanded by Colonel John Milton Chivington, attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment located on the high plains of Southeastern Colorado Territory. The assault lasted the better part of the day. When the bloodletting finally ended, more than 150 Arapahos and Cheyennes lay dead, the vast majority of whom were women, children, and the elderly. The next day, Chivington’s men burned what remained of the Indian village and took from the killing field grim trophies: scalps, fingers, and, some observers later insisted, genitalia hacked from their victims. The slaughter would come to be known as the Sand Creek Massacre. The massacre was rooted in the Civil War with local Colorado officials concerned that the Natives were being led astray by Confederate agents. It was also rooted in the 1858-1859 gold strikes west of Denver and the flood of newcomers eager to become wealthy and often ignoring tribal land claims and treaty boundaries who threatened to wash away the local indigenous people. The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were divided with some supporting the reservations created for them by the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty and the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise and others such as the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers opposed and willing in some cases to resort to violent resistance. At the beginning of the war the federal government has removed most of the regular army forces in the west to fight in the Civil War leaving it to locally raised militia to provide security. In the summer of 1862 the Federal government they failed in 1862 to deliver annuities required by treaty to the Cheyenne and Arapaho and to the Dakota in Minnesota. Hungry, the Dakota rose and killed hundreds of settlers in the Dakota War of 1862. Unrest among the tribes in Colorado grew throughout 1863 although it remained peaceful, but Governor Evans and others remained concerned that hostilities were imminent. In April 1864 Cheyenne Dog Soldiers fought briefly with a detachment of Colorado volunteers. In June Nathan Hungate and his family were murdered and butchered, inflaming fears of a Native uprising and over the summer violence by Colorado soldiers against the tribes was answered by violence by Natives against settlers. In August, the 3rd Colorado regiment of Indian fighters was raised from local volunteers. In September, a gathering of Cheyenne and Arapaho peace chiefs met with Governor Evans, Colonel Chivington now leading the 3rd Colorado and Major Edward Wynkoop (commander of Camp Weld) and Captain Silas Soule (an officer serving under Chivington) at Camp Weld. The tribes were still divided with many Dog Soldiers refusing to support the peace chiefs. The peace chiefs agreed to assemble those of their followers who wanted peace and to camp near Fort Weld which they did in early October. Governor Evans and Colonel Chivington faced a political dilemma after the Camp Weld meeting, Evans seeking higher political office and Chivington, erstwhile hero of Glorieta Pass, trying to cover himself in more glory by overstating the threat of an all-out war with barbarous tribes united in their desire to halt the march of white civilization into the West. A month later, on November 16, knowing that peaceful Arapahos and Cheyennes were waiting near Fort Lyon, Chivington started marching with the 3rd Colorado and elements of the 1st Colorado southeast from Denver. The chiefs camped with their bands along the banks of Sand Creek. Black Kettle, following instructions from Fort Lyon’s commander, flew an American flag over his lodge. The 3rd Colorado attacked at dawn. Captain Soule refused to allow the men under his command to participate. As soon as the massacre ended, the fight to define it began. Chivington claimed for the rest of his life that it was a glorious battle. Soule denounced it and testified to that effect before federal investigators. He was shot dead on the streets of Denver in 1865 by a soldier from the 2nd Colorado. Three federal investigations eventually determined that Sand Creek was a massacre. Efforts to challenge this narrative continued culminated in 1909 with a memorial to battles fought by Colorado soldiers in the Civil War which included Sand Creek. By 1950 the balance had swung somewhat and two historical markers were raised, one telling the story as Chivington had it and one with a mixed message “Sand Creek: ‘Battle’ or ‘Massacre’. The most recent twist in the saga of the memory of Sand Creek came in 1998 with the creation of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historical Site telling a balanced story about the event and vindicating Captain Silas Soule’s brave humanity 134 years earlier.

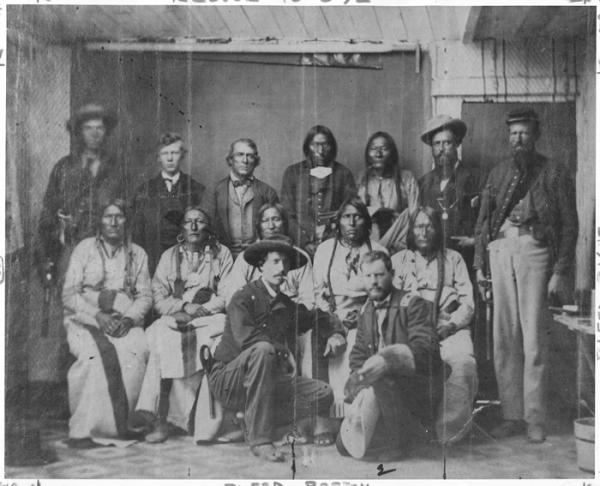

Black Kettle and Chiefs at Camp Weld, September, 1864. At the back are, (left to right), Unknown (Simeon Whiteley?), Dexter Colley, John Simpson Smith, Heap of Buffalo, Bosse, Gov. John Evans and Unknown. Seated are, (left to right), Neva, Bull Bear, at center, holding the peace pipe is Black Kettle followed by White Antelope and No-Ta-Nee, (Knock Knee). Maj. Edward W. Wynkoop, (on the left), and Capt. Silas Soule are kneeling in front. Photographed by Maj. Wynkoop's step-father-in-law, George D. Wakely.

Photo courtesy of History Colorado

On November 29, 1864, approximately 700 federal troops, commanded by Colonel John Milton Chivington, attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho camp located on the high plains of Southeastern Colorado. Some 1,000 Native Americans, who believed their leaders had forged a fragile peace with white authorities two months earlier, were stunned when the 3rd and part of the 1st Colorado Regiments descended upon them before dawn. The assault lasted the better part of the day. The frigid air echoed with the crack of rifles, the boom of artillery, and the shrill of screams. When the bloodletting finally ended, more than 150 Arapahos and Cheyennes lay dead, the vast majority of whom were women, children, and the elderly. The next day, Chivington’s men burned what remained of the Indian village and took from the killing field grim trophies: scalps, fingers, and, some observers later insisted, genitalia hacked from their victims. The soldiers than marched back to the city of Denver, where they received a hero’s welcome. The slaughter would come to be known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

Although Union forces did not square off with Confederates at Sand Creek, the massacre still exploded out of a Civil War context and later shaped how that conflict would be remembered in the West. Colonel Chivington and Colorado Governor John Evans understood hostility with Colorado’s Native peoples to be part of an archipelago of violence, ostensibly fomented in every instance by Southern intriguers working among the tribes. Conflict between settlers and tribal peoples ran from Minnesota, where the Dakota War had already claimed the lives of hundreds of settlers, to the Indian Territory, where Cherokees were still struggling against United States volunteers, and then through Colorado to New Mexico, where the Navajos, after enduring their Long Walk, had recently been forced onto a new reservation at the Bosque Redondo. In the spring and summer of 1864, Evans and Chivington managed to convince officials in Washington, D.C. that the Arapahos and Cheyennes, led astray by tribal factions reportedly in the thrall of rebel agents, represented an existential threat to the Republican Party’s plan to build an empire in the West, in this specific case fostering expansion and development along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. Confident that the Civil War could simultaneously function as a war of liberation and as a war of empire, Evans and Chivington leveraged racial anxiety and nationalism, persuading the federal government to foot the bill for an Indian war that ultimately engulfed the region.

The root rather than proximate cause of the Sand Creek Massacre can be traced back to 1858 and 1859, when gold strikes in the foothills west of Denver triggered a rush to the Mountain West. The resulting flood of adventurers, speculators, and gold seekers threatened to wash away Colorado’s indigenous peoples. Newcomers, abetted by territorial officials and protected by federal troops, often ignored tribal land claims, including the Cheyennes’ and Arapahos’ right, laid out in the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851), to a vast swath of territory that extended from the North Platte to the Arkansas Rivers and from the eastern slope of the Rockies to the western border of Kansas. After 1859, Arapahos and Cheyennes struggled to survive encounters with the shock troops of settler colonialism. Migrants, buoyed by the ideology of Manifest Destiny and steeped in currents of scientific racism—rhetoric promising that Indians would inevitably disappear in the face of white civilization—traversed Native lands, trampled crops and forage, and touched off periodic violence with the region’s indigenous peoples. In 1861, peace chiefs, including Black Kettle and White Antelope, hoped to secure their peoples’ future. Working with federal negotiators, they agreed to the Treaty of Fort Wise, which confined the tribes to a much smaller, triangular reservation in eastern Colorado.

That agreement fractured the Cheyenne and Arapaho polities. Only a small portion of the tribes’ chiefs had promised that their bands would abide by the details of the Fort Wise treaty. Meanwhile, leaders of military societies, especially the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, along with other militants, charged that the signatories were weak, ignorant, duplicitous, or perhaps all of the above. Even members of peaceful bands wondered if the new reservation, less than a tenth the size of the landholdings laid out in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, could possibly sustain their people. Some tribal belligerents refused to be bound by mere lines on a map, geographic borders that seemed abstract, arbitrary, or stinting. They insisted that they had never forsworn their right to hunt in western Kansas, where huge herds of bison still roamed. By contrast, white Coloradans, including Governor Evans, claimed that no matter how few tribal leaders had signed onto the Treaty of Fort Wise, all the Arapaho and Cheyenne people must abide by its strictures. With the backing of the federal soldiers who remained in the territory, Evans warned that failing to enforce the treaty could lead to all-out war.

He was half right; war did soon come, but not between Western settlers and Native American nations. Instead, Southern secessionists sundered the United States—an act of rebellion prompted in large measure by ongoing disagreements over how best to administer an emerging American empire in the West, and particularly the thorny question of whether the institution of slavery should be allowed in the trans-Mississippi territories. When the Confederacy began constituting itself as a new nation during winter and spring of 1860/1861, the Union belatedly started mobilizing for armed conflict. At that time, with the ink still wet on the Treaty of Fort Wise, most of the United States Army’s 15,000 or so soldiers were still stationed in the far West. But within just a few months, many of those men would be recalled back east, where they would, during the coming summer and fall, fight rebels rather than Indians. As some of those soldiers withdrew from Colorado, they left trepidation in their wake. Governor Evans later warned that, without federal troops watching over local tribes, hostile Indians would run wild. Ignoring the diplomatic and political divisions that plagued the region’s Native peoples, he suggested that a vast confederation of warriors, likely collaborating with Confederate agents, conspired to wipe out the territory’s white population.

The threat of rebels working in cahoots with the West’s indigenous peoples, though usually little more than a settler’s fever dream, seemed real enough when set against the backdrop of the disintegrating Union. In the early spring of 1862, for example, Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley launched his New Mexico Campaign, an invasion designed to hive off much of the Southwest from the United States. Sibley’s advance culminated outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Union forces there, arrayed under Colonel John Potts Slough, commander of the 1st Colorado Regiment, won a major victory when troops under John Chivington, at the time still holding the rank of major, helped to cut the enemy’s supply lines. Sibley’s forces had to retreat to safer ground. Chivington’s men had blunted further Confederate incursions into the region, and Chivington became a hero for many Westerners.

Further north, the federal government, financially overburdened by the cost of fighting the Civil War, failed throughout the summer of 1862 to deliver the annuities promised by treaty to the Arapahos and Cheyennes in Colorado and to the Dakotas in Minnesota. The tribes went hungry. Dakota warriors near St. Paul, Minnesota responded in late August by killing hundreds of settlers at the start of what became known as the Dakota War of 1862. President Lincoln responded to the crisis by dispatching Major General John Pope, after his recent failure at Second Bull Run, to restore the peace. The day after Christmas 1862, thirty-eight Dakotas, supposedly ringleaders in the uprising, were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest public execution in United States history. But the fighting continued for months after that, casting a pall as far away as Colorado. Some Cheyennes and Arapahos, facing starvation, ventured outside their reservation for food. The number of skirmishes between settlers and Native people increased during the fall of 1862 and even more so the next spring. In May, Governor Evans, spooked by rumors of an impending accord between Arapahos, Cheyennes, Comanches, and Kiowas, and worried that the violence still raging in Minnesota might soon make its way to Colorado, warned local tribes that Union soldiers would fight a war of extermination against local Indians if they joined such a federation.

Native nations in Colorado grew more restive in summer 1863, deepening Governor Evans’s conviction that the territory might soon face a general Indian war. In August, belligerent Utes began raiding mountain settlements. John Chivington, by then promoted to the rank of colonel and in command of the Military District of Colorado, sent a battalion from the territory’s 1st Regiment to pursue and chastise the hostile warriors. While those troops were in the field, Evans tried to parley on the plains with a group of peace chiefs, including Black Kettle. But the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers, flexing their political muscle, refused to allow that meeting to take place. In September, Evans, increasingly agitated, received word that the Arapahos, Cheyennes, Kiowas, and various Sioux bands were preparing for war with whites in the region. The governor began corresponding more frequently with federal officials, both in the Interior and War Departments, warning them about the peril facing Western settlers. The Cheyennes and Arapahos, meanwhile, appear to have been more focused in that moment on eking out a bare subsistence. News from Fort Lyon, a federal installation located near the Kansas border, suggested that many Indians would go hungry in the coming winter.

Despite a peaceful winter, Governor Evans remained convinced that hostilities with Indians would resume as soon as spring arrived. In March 1864, Cheyenne peace chiefs, once again including Black Kettle, conferred in Kansas with their Indian agent, asking that he convey to Evans tidings that the tribe was not united in its desire for war with whites. Evans, by then convinced that the Arapahos and Cheyennes were monolithic and hell-bent on bloodshed, ignored the information. The following month, Colonel Chivington received orders from his superiors to send most of the 1st Colorado Regiment to push back against Confederates massed near the territory’s southeastern border. Chivington suggested to Evans that the governor should lobby Washington for the right to raise a regiment devoted exclusively to protecting white settlers from Indian depredations. Evans agreed and began sending out a string of increasingly frenzied dispatches, suggesting that Colorado’s settlers confronted mortal peril.

The next month, events seemed to substantiate Governor Evans’s claims. On April 12, a skirmish took place between a group of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers and a detachment of federal soldiers in northeastern Colorado. Several Native people died in the struggle—the precise number was a matter of dispute—and events in the territory spun out of control. Months of escalating violence ensued. Settlers descended into a state of panic. Evans’s mood mirrored that of the people he governed. The governor’s requests to federal officials for more troops and more material support became frenzied. Colonel Chivington embraced eliminationist rhetoric, writing to the commander of Fort Lyon: “The Cheyennes will have to be soundly whipped before they will be quiet. If any of them are caught in your vicinity, kill them, as that is the only way.” Chivington suggesting to his subordinates that they should not bother trying to differentiate between hostile and friendly Indians, sorting Dog Soldiers from peaceful bands, but instead that an indiscriminate war without mercy might be the only path to victory. [1]

On June 11, a man named Nathan Hungate tended stock on a ranch roughly thirty miles southeast of Denver. As Hungate worked, he noticed smoke rising from the ranch house. He sprinted toward the fire, thinking of his family inside. When neighbors later arrived, they found Hungate, his wife, and their daughters dead. The corpses had been scalped. Onlookers assumed that Indians were responsible for the murders. The crowd transported the broken bodies to Denver, where they rested in public: a memorial; a cautionary tale; and an incitement to further violence, acts of vengeance against “hostile savages.” As news of the slaughter circulated, terrified settlers, fearing an all-out assault from belligerent tribes, poured into Denver from the plains. The Hungates’ ruined corpses became the centerpiece of a community gripped by collective panic. When rumors of additional Indian attacks spread, they pushed the city over the edge. On June 15, reports surfaced that a force of Native warriors, many thousands strong, stood poised to lash out at Denver. But the attack never arrived. Instead, the army of hostile Indians turned out to be a massive herd of cattle kicking up dust on their way to market.

Governor Evans’s pleas to federal officials grew shriller as the situation deteriorated. He warned that settlers in Colorado would, absent adequate protection, face the same fate that Minnesotans had two years earlier. Military authorities responded that the Confederate rebellion, especially action in Missouri, remained a more pressing concern. On June 27, Evans issued a proclamation to the territory’s friendly Indians, requesting that they present themselves at places of sanctuary, including Fort Lyon. Native people who did not comply with his directive, Evans warned, would be punished. The gambit seemed to work. Calm settled over Colorado’s eastern plains. In mid-July, though, soldiers shot and killed Left Hand, a leader among the Arapaho and Cheyenne peace chiefs. Infuriated tribal warriors retaliated against settlers. The violence spun out of control again. Black Kettle, still hoping to work with Governor Evans, tried to reopen negotiations in August. It was too late. On August 11, Evans issued a second proclamation, this time urging Colorado’s citizens to pursue and kill the territory’s hostile Indians. Members of these state-sanctioned mobs, he promised, would be rewarded with the property of their victims. The next day, Evans received authorization from the War Department to raise a regiment of Indian fighters, the 3rd Colorado.

Nevertheless, Black Kettle would not give up on the possibility of a truce. Late in August, he convened a council of Arapahos and Cheyennes. Several members of the tribes’ soldier societies stood with the peace chiefs. But many of the Dog Soldiers refused their entreaties. After those warriors stormed out of the meeting, Black Kettle kept working, eventually composing a peace overture with the help of George Bent, son of William Bent, a borderlands businessman who owned a trading post called Bent’s Fort, and Owl Woman, his Cheyenne wife. Black Kettle then dispatched tribal envoys to carry the letter to military personnel at Fort Lyon. On September 6, scouts at the fort spotted the delegation, whose members waved a white flag to signal their peaceful intentions. Major Edward W. Wynkoop and Captain Silas Soule met with the Indians. Eventually convinced of their sincerity, Wynkoop and Soule agreed to travel to their camp. Once there, they recovered several white captives taken earlier in the summer and agreed to bring the peace chiefs to Denver, where they could meet with Colonel Chivington and Governor Evans. On September 26, the party arrived in the capital. Evans, though initially unwilling meet with the peace commissioners and enraged with Wynkoop and Soule for having bucked protocol, eventually relented.

On September 28, Governor Evans and Colonel Chivington gathered on the outskirts of Denver at Camp Weld, with the peace chiefs, Major Wynkoop, and Captain Soule. Soule later recalled that the Native leaders were eager to begin discussions. Evans, though, pointed to the Civil War and insisted that he did not have the authority to negotiate any accord. The Arapahos and Cheyennes were at war with the Union, he said, and therefore must work with military authorities. Chivington also demurred, leaving it up to Wynkoop to decide the fate of the Native delegation. Wynkoop told the Native leaders that if they wanted peace, they should gather like-mind people in their tribes, go to Fort Lyon, present themselves to the commander there, subject themselves to martial law, and make camp nearby. Black Kettle and the other chiefs understood that if they complied with Wynkoop’s directive, they would be under the protection of the United States flag. Less than a week leader, the peace commission left Denver. They arrived at Fort Lyon on October 8. Black Kettle and the other chiefs then rode east to reconvene with their bands, explain the terms they had secured in Denver, and then, about ten days later, return to Fort Lyon, where they thought they would be safe.

Governor Evans and Colonel Chivington faced a political dilemma after the Camp Weld meeting. The 3rd Colorado Regiment’s term of enlistment was just one hundred days long. By mid-October, more than half of that period had already passed. Critics throughout the territory began charging that these so-called Indian fighters were actually free-loaders, cowards and ne’er-do-wells; that Evans was more concerned with Colorado’s struggle for statehood and with securing for himself a seat in the U.S. Senate than he was with protecting settlers besieged by “savages” on the plains; and that Chivington, the erstwhile hero of Glorieta Pass, had tried to cover himself in more glory by overstating the threat of an all-out war with barbarous tribes united in their desire to halt the march of white civilization into the West. A month later, on November 16, knowing that peaceful Arapahos and Cheyennes were waiting near Fort Lyon, Chivington started marching with the 3rd Colorado southeast from Denver. The chiefs camped with their bands along the banks of Sand Creek. Black Kettle, following instructions from Fort Lyon’s commander, flew an American flag over his lodge.

The 3rd Colorado arrived at Fort Lyon on November 28. Chivington set up pickets around the post and ordered them to shoot any man from the 1st Colorado who tried to leave. He then instructed the fort commander to provide him with a company of troops to join in the assault the following morning. Captain Soule and a contingent of officers from the fort objected to the plan. They explained that the Arapahos and Cheyennes at Sand Creek were effectively prisoners, and that they were protected by the truce they had agreed to with Colonel Wynkoop. Firing upon them, Soule later recalled insisting, would be tantamount to murder. The dissenters incensed Chivington, who threatened to kill any man who refused to obey his orders. At approximately 8:00 p.m., Chivington, the men of the 3rd Regiment, and a group of soldiers from the 1st Colorado embarked on what would be a frigid, forty-mile march to Sand Creek.

The troops arrived at the peace camp just before dawn. Some of them were drunk. Colonel Chivington delivered a fiery speech about the need to avenge the Hungate family and other settlers who had suffered during the previous years of violence. The enflamed men attacked without any warning, initially scattering the unsuspecting Arapahos and Cheyennes and then, as the morning wore on, driving many of them up the dry creek bed. As the onslaught continued throughout the day, some Indians dug makeshift shelters in the sandy soil, trying to protect themselves and their loved ones from rifle and howitzer fire. The 3rd Colorado fought without mercy. Soldiers reportedly visited terrible cruelties upon the living and the dead: killing Indians who tried to surrender, disemboweling a pregnant woman, desecrating corpses. Captain Soule, for his part, refused to commit the men under him to the slaughter. They stayed out of the fray, documenting atrocities and further provoking Chivington’s partisans.

As soon as the massacre ended, the fight to define it began. With Cheyenne and Arapaho corpses still cooling nearby, Chivington wrote a series of reports to his superiors and to the press in Denver. He understood the violence at Sand Creek as a noble part of civilizing the American West and of preserving the Union—indeed, he believed those processes were inextricably intertwined. And so, he used the gallons of blood spilled along Sand Creek’s banks to depict a masterstroke. His outnumbered men, Chivington recounted, had attacked an Indian village bristling with more than 1,000 warriors. Despite those long odds, the fight had gone well. His troops had killed several chiefs and hundreds of their followers. Chivington then justified the attack by pointing to depredations allegedly committed by the fallen enemy during raids the previous summer. His men, he said, had whipped savages guilty of desecrating white bodies, including, and here he alluded to the brutal Hungate murders, the bodies of innocent women. Surely this was an outrage that demanded a quick reprisal dealt by a sure hand.

For the rest of his life, Chivington reiterated that Sand Creek had been a glorious battle. He pointed to the backdrop of the Civil War and to the settlers’ remains he claimed his men had recovered from the scene. In spring 1865, for example, Chivington testified before a federal inquiry investigating the violence. He waved the bloody shirt, insisting that Confederate emissaries had wormed their way into the Arapahos’ and Cheyennes’ good graces, whipping them into a violent fury. “Rebel emissaries were long since sent among the Indians to incite them against the whites,” he claimed. Chivington alleged that George Bent—who, until he was captured and then paroled by Union troops in the summer of 1862, had fought under General Sterling Price in the 1st Missouri Regiment—had served as the South’s representative, exhorting his kinsmen that with federal troops busy elsewhere fighting rebels, they should reclaim their hunting grounds: “the Great Father at Washington having all he could do to fight his children at the south, they could now regain their country.” In this way, Chivington made his victims at Sand Creek enemies not just of settlers in Colorado but of the Union more broadly; the bloodshed became not just a triumph in the Indian Wars but also in the Civil War. Finally, in 1883, Chivington addressed a Colorado heritage organization at its annual banquet. He added details about atrocities committed against whites in the months leading to November 1864 before concluding his remarks by announcing that he remained proud of the actions of the 3rd Colorado Regiment at Sand Creek. [2]

Captain Silas Soule, by contrast, was ashamed of his association with the massacre. Having refused to commit the troops under him to the fight at Sand Creek, Soule later inverted Colonel Chivington’s claims about the episode. Three weeks after the violence, Soule wrote to a friend. The slaughter, he noted, had sullied the honorable fight for the Union and the process of settling the West. He said that Native, not white bodies, as Chivington claimed, had been desecrated there. When Soule testified in the spring of 1865 before federal officials investigating the bloodshed at Sand Creek, he recounted how the peace chiefs, after the Camp Weld meeting, had complied with Colonel Wynkoop’s orders and had thus believed that federal troops were protecting them. Within weeks of his testimony, Soule’s story took on added resonance. On April 23, 1865, a soldier from the 2nd Colorado Cavalry killed Soule in the streets of Denver. President Lincoln had been assassinated just a week earlier, and Soule’s murder, like Lincoln’s, spawned conspiracy theories, including the story that Chivington had paid to have Soule silenced. For many onlookers, Soule’s Sand Creek memories became the unimpeachable recollections of a man martyred for speaking truth to power.

Three federal investigations eventually determined that Sand Creek had been a massacre, but Colonel Chivington and many Westerners refused to accept those findings. And because Sand Creek represented such an unsettled chapter in the region’s Civil War history, the fight over its memory continued. In 1879, for instance, author Helen Hunt Jackson embraced the cause of Indian reform. In letters to newspapers nationwide, she drew on Silas Soule’s memories, using Sand Creek as a cudgel. The Indians at Sand Creek, she said, had been peaceful and guaranteed protection by federal authorities, and Chivington’s troops had treated the dead in an unspeakable manner. Her charges rankled William Byers, who, as editor of the Denver Rocky Mountain News in 1864, had dismissed claims that Sand Creek had been a massacre. Byers ignored the ongoing Indian Wars, replying to Jackson that Sand Creek had pacified the Plains tribes. He also said that Jackson, a woman from New England, could not possibly understand the violence; she possessed effete sensibilities out of place in the rough-and-tumble West. Jackson rebutted Byers’s sexism with nationalism. The violence after Sand Creek, she noted, had occupied thousands of troops who might otherwise have fought Confederates. Sand Creek had not only been a massacre, it had detracted from the Union war effort.

As Jackson sparred with Byers, she worked on a book about the nation’s longstanding mistreatment of its indigenous peoples. Century of Dishonor, published in 1881, was a relentless exposé of the federal government’s repeated violations of its treaties with Native Americans. Only by overhauling its Indian policy, Jackson said, by placing Indian affairs in the hands of the government’s civilian branch, could the United States be redeemed in the eyes of God. With the Modoc War, the Red River War, and the Great Sioux War, including what was then known as the Custer Massacre at the Little Bighorn, just over, some officials in the Interior Department were primed to embrace Jackson’s calls for reform. But even with the climate surrounding federal-tribal relations shifting, Colonel Chivington’s perspective still had adherents, While Jackson worked on Century of Dishonor, editors at Colorado newspapers called for “another Sand Creek” to wipe out the Utes in the wake of the infamous Meeker Massacre.

Infuriated by such sentiments, George Bent, who, after he was wounded at Sand Creek, fought for years to keep memories of the massacre alive, began relating tribal lore to a historian named George Hyde. In 1906, Bent and Hyde published six articles in a magazine called The Frontier. Those essays, which appeared under Bent’s name, debunked Chivington’s Sand Creek story. Although Bent acknowledged that he had fought with the Confederacy, he mocked Chivington for his paranoia about rebel plots and for misunderstanding Native diplomacy. The Kiowas and Comanches, Bent wrote, hated Texans, and the Arapahos and Cheyennes, though hardly staunch Unionists, had no incentive to fight with the Confederacy. Turning to the massacre itself, Bent related details of Chivington’s betrayal of the peace chiefs; of Black Kettle raising white and American flags over his lodge to signal that his people were friendly; and of the Colorado troops’ butchery. Bent then considered the implications of the violence. He seemed to understand the Civil War as a war of imperialism rather than liberation, a moment when the United States began to consolidate its control over its western territories.

Bent’s essays rankled Colonel Chivington’s surviving men. Major Jacob Downing resented the charge that he and his comrades had perpetrated a massacre, dishonoring their otherwise-noble Civil War service, and that an Indian dared to suggest that a white man might be uncivilized. With veterans of the war nearing the end of their lives nationwide, Downing began trying to embed Chivington’s Sand Creek memories in a narrative that heritage groups were constructing around the United States: archives were acquiring document collections, authors were publishing regimental histories, and cities were unveiling monuments and memorials. These efforts were intended to inspire onlookers to embrace a reconciliationist narrative of the Civil War. The conflict’s root causes—struggles over the fate of slavery, over competing definitions of federal authority and citizenship, and over control of the West—could be set aside in service of an amicable reunion between North and South. In other words, upholding patriotic orthodoxy demanded collective amnesia rather than remembrance. This work culminated in Colorado with the unveiling, in 1909, of a memorial on the state capitol steps. The monument featured a plaque cataloging battles in which the state’s soldiers had fought during the war. Sand Creek was among them. The memorial’s sponsors had smoothed away the massacre’s rough edges and cast Chivington’s story in bronze.

Forty years later, Coloradans, working in a different political context, reversed course. They began segregating memories of the massacre from those of the Civil War and associating the Sand Creek bloodshed exclusively with the process of westward expansion. On August 6, 1950, the state unveiled two historic markers. The first, a marble slab, sat on a rise overlooking the massacre site. It echoed Colonel Chivington, reading, “Sand Creek Battle Ground.” The second, an obelisk sponsored by the state historical society, included the mixed message, “Sand Creek: ‘Battle’ or ‘Massacre,’” and labeled the bloodletting “a regrettable tragedy of the conquest of the West.” Leroy Hafen, Colorado’s state historian at the time, oversaw the dedication ceremonies and struggled with how to remember Sand Creek. He explained to his audience that the event had been called both a battle and a massacre through the years. Ducking that fight, Hafen described the violence as a tragedy born of the process of settling the West. He elided responsibility for Sand Creek and divorced it from the Civil War. This made sense at the start of the Cold War. Federal authorities drummed up support for internationalism by encouraging Americans to recall the Civil War as an emblem of the nation’s commitment to freedom. Sand Creek, bathed in an increasingly ambiguous light in these years, did not fit with this vision of the Civil War as an unalloyed good war.

Throughout the 1960s, still more changes in the nation’s cultural and political climate seeded the ground for yet another reappraisal of Sand Creek. And so, when a librarian and historian named Dee Brown published a book called Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee in 1970, the civil rights movement was maintaining a steady focus on issues of racial inequality; many people, part of the so-called New Age, were fascinated by traditional indigenous cultures; and Americans had once again confronted the capacity of U.S. soldiers sometimes to slaughter civilians. Brown’s book thus found an audience eager to learn more about Native Americans and keen to embrace critiques of militarism and racism. When writing about Sand Creek, Brown adopted a narrative arc and interpretive frame similar to Silas Soule’s and George Bent’s. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee spent more than a year on the Times bestseller list and has sold more than 5 million copies. It also has had an enormous influence on readers, including a rising generation of scholars who later identified themselves as New Western historians.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee’s impact could still be felt in 1998, when Congress passed legislation calling for the creation of a Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. It took eight more years, filled with wrangling over the massacre’s history and geography, before the National Park Service was ready to open the first unit of the Parks System that would label American troops perpetrators rather than heroes or victims. The Sand Creek site now offers its visitors a story of the massacre, and of the context in which that violence took place, that bucks the redemptive, reconciliationist currents that run through the vast majority of national historic sites in this country. The massacre site indicts characters—citizen soldiers, overland pioneers, Union officials—often cast as heroes in the collective memory of the American imagination. The history of Sand Creek, as presented at the historic site, reflects a darker vision of the Civil War’s causes and consequences, focusing on ironies that punctuate the nation’s past.

- [1] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 33, part 2, p. 300 (hereafter cited as O.R., I, 33, pt. 2, 300).

- [2] “Testimony of Colonel J. M. Chivington, April 26, 1865,” in Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, H.R. Rep. No. 38(2) (1865) part 3, Massacre of the Cheyenne Indians, 106.

If you can read only one book:

West, Elliot. The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Books:

Carroll, John M. Sand Creek Massacre: A Documentary History 1865-1867. New York: Sol Lewis, 1973.

Greene, Jerome A. and Douglas D. Scott. Finding Sand Creek: History, Archeology, and the 1864 Massacre Site. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Hahn, Steve. A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830-1910. New York: Viking Press, 2016.

Halaas, David F. and Andrew E. Masich. Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent – Caught Between the Worlds of the Indian and the White Man. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2004.

Hoig, Stan. The Sand Creek Massacre. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

Hyde, George E. and Savoie Lottinville. Life of George Bent: Written from His Letters. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968.

Kelman, Ari. A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Roberts, Gary L. Massacre at Sand Creek: How Methodists Were Involved in an American Tragedy. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2016.

Organizations:

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

The National Park Service manages the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. The site is open from 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. 7 days a week from April 1-November 30 and Monday-Friday from December 1-March 31 and there is a visitor center. Their address is 910 Wansted, POB 249, Eads, CO, 81036-0249, 8 miles north of the town of Chivington.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

University of Denver’s John Evans Study Committee

University of Denver’s John Evans Study Committee

Northwestern University’s John Evans Study Committee

Northwestern University’s John Evans Study Committee investigated and reported on the role of Colorado Governor John Evans, founder of the University, in the Sand Creek Massacre.