The US Sanitary Commission

by Patricia L. Richard

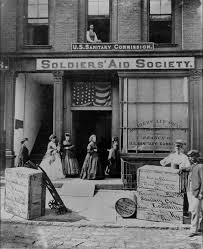

United States Sanitary Commission | USSC | Elizabeth Blackwell | Emily Blackwell | Women’s Central Relief Association of New York | Henry W. Bellows | Frederick Law Olmstead | Medical Reform Bill 1862 | Katherine Wormeley | Sanitary Commission Bulletin | USSC Army and Navy Claim Agency.

On October 29, 2012 Hurricane Sandy struck heavily populated areas of New York and New Jersey. The storm tore down power lines, flooded streets, and destroyed homes. In the wake of the second costliest storm in U.S. history, the Red Cross responded with relief efforts and by asking for donations. After the first harrowing days were over, Red Cross representatives assured Americans that they had successfully “delivered food, clothes and shelter to tens of thousands of people left homeless by the storm.” The familiar sight of Red Cross trucks and volunteers handing out supplies to survivors communicated that Americans were taking care of their own. In 2014, journalists revealed that the Red Cross lied about their actions after Sandy. In an NPR and ProPublica interview, top Red Cross officials disclosed that they had difficulty meeting the needs of storm survivors. And worse, they provided documents that “depict an organization so consumed with public relations that it hindered the charity’s ability to provide disaster services.” The validity of these accusations is immaterial to this essay, but, rumored misconduct in a U.S. humanitarian service, however, has a historical precedent. [1]

The precursor to the Red Cross, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), also struggled with allegations of mismanagement. In 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War, the USSC pledged to provide sanitary counsel to the U.S. Army and medical supplies and food to wounded Union soldiers. Two years later, Northerners accused the USSC of corruption. The parallel deception charges thrown at the Red Cross and the USSC provides an opportunity to examine the relationship between these relief organizations and the public who aid them. The Red Cross developed an international reputation for its ability to help wherever disaster strikes. Maintaining this image and keeping donations flowing became sometimes more important than delivering the fabled service. Similarly, the USSC lost the trust of its supporters because efforts to create and maintain a national benevolent organization eclipsed the work of individuals and the communities they served. Both started as a noble enterprise but the large bureaucratic apparatus needed to accomplish their missions drove leadership apart from the people they served and the people who supported them. For both organizations, trust became a complex issue. This is a story about how the USSC gained the trust of the northern public, how they lost that trust, and how they attempted to regain it.[2]

The United States Sanitary Commission, like many bureaucratic organizations, evolved and grew. The USSC emerged in a time of crisis at the beginning of the Civil War. On April 15 1861, a day after the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate troops, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 men to put down the rebellion. Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister Emily, founders of the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, outlined a plan to meet the medical needs of Union soldiers by organizing war relief and by supervising a corps of female nurses to work in military hospitals. Elizabeth was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States and was an associate of Florence Nightingale. She and her sister invited women and men from elite families in New York City’s boroughs to meet at Cooper Union. Nearly four thousand people gathered on April 26, 1861 and formed the Woman’s Central Relief Association of New York (WCRA). Their goals included to “‘give organization and efficiency to the scattered efforts’ already in progress; gather information on the wants of the army; establish relations with the Medical Staff of the army; create a central depot for hospital stores; and open a bureau for the examination and registration of nursing candidates.” Their board of managers included twelve women and twelve men. The men had final authority, but women held prominent positions.[3]

The men quickly took control of the whole enterprise. The Blackwell sisters invited Henry Whitney Bellows, Unitarian minister of the All Souls Church in New York City, to be an organizing member. On May 15, Bellows along with New York City physicians William Holme Van Buren, Elisha Harris, and Jacob Harsen traveled to Washington, D.C. to evaluate the “government’s management of military medical affairs,” ostensibly as representatives of the WCRA. By the time they arrived in D.C. the group had invented a male-run organization that would be more “forceful and authoritative” than the WCRA. Modeling this new entity on the British and French Sanitary Commissions established during the Crimean War (1854–1856), they called it the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). The WCRA became a branch and subordinate to the Washington D.C.-based USSC.[4]

Bellows hoped to nationalize benevolence and use scientific advances to avoid the ravages of disease experienced by the British and French troops during the Crimean War. Bellows proposed to the Secretary of War Simon Cameron and the Surgeon General Clement A. Finley the Medical Bureau would benefit “from the counsels and well-directed efforts of an intelligent and scientific commission.” He promised that the commission would not “interfere with but” would “strengthen the present organization” with advice from advances in medical science. Bellows asked for no legal powers but wanted government sanction to confer with the Medical Bureau and War Department. They received official status from the War Department June 9 and President Lincoln signed the order on June 13, 1861. Relief efforts could now be national in scope.[5]

They began with great enthusiasm but were met with caution. Immediately after the USSC organized, Bellows and an associate secretary visited the troops gathering on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Commission secretary Frederick Law Olmsted and Elisa Harris visited the forces in the East. They conducted “systematic sanitary inspections” of the military camps and found appalling conditions. Filthy living, poor hygiene and the habit of soldiers frying all of their food in bacon grease led to a prevalence of diarrhea, dysentery, and typhoid among the troops. Olmsted sent out Circular Addressed to the Colonels of the Army in the early summer of 1861, placing responsibility on the regimental officers for the health of their men and advising them they could avoid diseases with “strict cleanliness and proper preparation of good food.” Although the USSC had official sanction, they met resistance from all levels of government and in the military from regimental to company commanders. Some officers listened to their advice. Most officers, though, believed they knew best and saw the USSC agents as meddlesome civilians. Even Lincoln saw the Commission as “a fifth wheel to a coach.” They had to earn the trust of the men they wanted to help.[6]

They also needed to convince civilians that a system of nationalization under the USSC was the “best and safest channel” for their gifts. They justified more systematic organization with stories that women’s earlier efforts led to chaos. Across the North, women responded to Lincoln’s call for troops by providing food, clothes, and blankets for their local regiments. Like many others, they believed the war would not last long and so did not organize beyond immediate needs. Recognizing more action was needed, the USSC sent a letter to the “Loyal Women of America” persuading them to establish “societies dedicated to soldier relief” which would be “answerably solely to the central agency.” Mary Livermore, manager of the Northwest Sanitary Commission in Chicago remembered those early days of the war when “women rifled their store-rooms and preserve closets of canned fruits and pots of jam and marmalade, which they packed with clothing and blankets, books and stationery, photographs and ‘comfort bags.’” Eventually, “baggage cars were soon flooded with fermenting sweetmeats, and broken pots of jelly that ought never to have been sent.” Delayed trains led to “decaying fruit and vegetables, pastry and cake in a demoralized condition, badly canned meats and soups,” all of which were “necessarily thrown away en route. And with them went the clothing and stationary saturated with the effervescing and putrefying compounds which they enfolded.” Worse, they argued, packages were frequently lost because of the constant movement of troops. “Out of this chaos of individual benevolence and abounding patriotism the Sanitary Commission” pledged to organize the “lavish outpouring of the people” with “its carefully elaborated plans, and its marvelous system.” System, order and nationalization became the watchwords of the Sanitary Commission. Convincing local aid society leadership that such a large scale plan was needed became paramount to their success.[7]

Olmsted and Bellows also inspected military hospitals and likewise found them in disarray. Mary Livermore explained the problem that “before the war there was no such establishment as a General Hospital in the army. All military hospitals were post hospitals, and the largest contained but forty beds. There was no trained, efficient medical staff. There were no well-instructed nurses, no sick-diet kitchens, no prompt supply of proper medicines, and no means of humanely transporting the sick and wounded.” As an attempt to remedy some of these problems, USSC officials lobbied for the Medical Reform Bill throughout 1861 in hopes of changing the current system of promotion of Medical Bureau surgeons by seniority over merit. They wanted to insert younger surgeons who were more familiar with the latest medical advancements and who were less rigidly tied to army precedents. The bill passed and was signed by President Lincoln on April 16, 1862. The Surgeon General Finley was replaced by the USSC’s candidate William A. Hammond who began a campaign to reorganize the Medical Bureau to be more responsive to the demands of war and to update many of its medical practices. Senior physicians in the military would target Hammond and the USSC for these acts.[8]

Before this success, however, the rout of Union troops at the Battle of First Bull Run, July 21, 1861, revealed to the public the dire need for improvements in medical care and training of the citizen soldiers. It became apparent that Union forces lost at Bull Run because of poor discipline and training. The discipline, so said the Commission, needed to begin in camps with better personal hygiene and care and direction from officers. Training would come from the newly appointed general to the Army of the Potomac, Major General George Brinton McClellan. Civilians were awakened to the idea of a longer war and began establishing soldiers’ aid societies affiliated with the Commission and sending “material aid.” According to Sanitary records, it was this “spontaneous opening of the never failing fountains of woman’s sympathy and aid for the sick and wounded that fully inaugurated the Sanitary Commission’s department of Relief.” The medical arrangements in the military were outdated and woefully inadequate for the complicated battlefield. The commission was the front line in that battle. Although they would gain some support over the next year, they made enemies of officials who lost power because they lobbied for changes in the Medical Department and military.[9]

General McClellan’s training of the Army of the Potomac lasted through the fall of 1861 into the early spring of 1862. Finally in March 1862, McClellan decided to attack Confederate troops near Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, by way of the York Peninsula. This first big military campaign lasted months and combined all the challenges of relief as a modern day super storm Sandy. Preparations for the campaign were known to the Northern public as early as February 1862. Northern commanders had the difficult task of keeping their troops supplied in unfriendly territory with long supply lines. Quartermaster General Montgomery Cunningham Meigs organized an impressive flotilla of 400 ships and barges to transport 100,000 men, 300 cannon, 25,000 animals and mountains of equipment. Once on the peninsula, Medical Director of the Army Brigadier General Charles Stuart Tripler created a series of field stations to provide initial care to wounded soldiers and then convey them to hospital ships which would then transport them to northern hospitals. Although Tripler believed he had created a system that could easily handle the influx of wounded soldiers, he had not anticipated the 121,000 sick men to be cared for combined with the battlefield casualties. His structure would begin pulling apart at the seams and it was only the help of civilian organizations like the USSC that slowed the collapse. [10]

USSC leaders anticipated the medical concerns and complications this campaign presented and approached the Medical Department offering to “supplement its provisions with stores of their own.” Frederick Olmsted, in the meantime, cobbled together a fleet of ships not being used by the quartermaster corps that he cleaned and converted into floating hospitals providing beds, food, medical supplies and a civilian medical staff. His fleet consisted of eight ships and one small supply tender. Immediately upon arriving at the peninsula, the issue of the sick became apparent. The small streams and rivers, swamps and marshes presented a “jungle-like atmosphere” that became visible in the form of disease among the soldiers. Men became ill with among other things, “cholera, malaria, acute diarrhea and dysentery, epidemic bronchitis, typhoid and typhus, purulent eye disorders, boils, and scarlet fever.” As the first fighting began, many of the medical officers did not want to be bothered by the sick of their regiments and tried to pawn them off on the sanitary boats, or worse left the sick men to fend for themselves.[11]

Katherine Wormeley, part of the elite staff handpicked by Olmsted to work on the ships, compared government-organized care to Commission care. After the battle of Fair Oaks, Commission boats “filled calmly and comfortably on Sunday and Monday with wounded from Saturday,” she wrote. Then the government boats filled and produced “such fearful scenes”. From five to eight hundred wounded were sent down daily with “no authorized officials to receive them” and “no arrangements of any kind.” These government boats had been lying idle for weeks, according to Wormeley, “waiting for surgical cases” with their surgeons off to the battlefield. These boats had “no beds, no hospital stewards, no food, no stimulants.” As the wounded arrived “the medical authorities fling themselves on the Sanitary Commission.” Concerned with the wounded, Commission staff took over on three-fourths of the government boats, “and that at the last moment, without notice, and when its supplies were heavily taxed in fitting out its own boats.” Although the Commission helped, “it had no power; only the right of charity.” Proving its worth, Wormeley noted, the Sanitary Commission “did nobly what it could.” The USSC also did its noble work during the battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donnelson and Shiloh. By summer of 1862, the USSC was beginning to make headway among the army brass and doctors and with the northern public. [12]

The USSC never could rest on its laurels, though, because its growing bureaucracy began to hinder its actions. The rumors started as early as November 1861 in a letter to editor of the New York Times. As historian Jeanie Attie explains, the letter “spoke of ‘suspicions and doubts’ claiming that “boxes filled with homemade goods and sent to the WCRA office in New York City were not being forwarded to the army for ‘want of method’.” USSC leaders ignored these accusations as nothing more than rumors not warranting a reply. By September 1862, more specific accusations began coming in about lack of oversight. Others claimed that the soldiers never received the goods and still others accused the army and medical staff of stealing the food and wine and consuming it themselves. Or worse, that the USSC representatives meant to distribute these supplies were actually selling the items to the soldiers for profit. Mary Livermore remembered, “Over and over again, with unnecessary emphasis and cruel frequency, officers, surgeons, and nurses were adjured, through notes in the boxes.” “For the love of God,” one woman wrote “give these articles to the sick and wounded to whom they are sent!” Another intoned, “Surgeons and nurses, hands off! These things are not for you, but for your patients,-our sick and wounded boys.” Livermore assured her readers that “There was more honesty in the hospitals, and much less stealing by the officials, than was popularly believed.” Chaos of the battlefield possibly caused boxes to be lost and wounded to not receive items or care from the USSC. Regardless, damaging rumors swirled. [13]

Considering the number of employees and the representatives tied to the USSC, it’s no wonder northern civilians became suspicious. As the fighting between Union and Confederate armies increased so too did the demands on the USSC. They created a standing committee (which met every day) to meet these pressures. The standing committee included five commissioners: Henry Bellows, George Templeton Strong, William Van Buren, Cornelius Rea Agnew and Oliver Wolcott Gibbs. General Secretary Olmstead informed the two associate secretaries of the decisions of the standing committee (one in the east based in Washington, D.C. and one in the west based in Louisville, Kentucky). Under the associate secretaries were assistant secretaries who were responsible for the running of the office and who had office employees, a property clerk and a document clerk. Field relief agents and inspectors worked for the USSC on the battlefields. Along with these agencies they added the Statistical Department to investigate the needs of the army. These agents went to the military camps and collected statistics to direct their work. Frederick Knapp established the Special Field Relief department and set up soldiers’ homes in towns frequented by traveling soldiers to provide food, lodging, and medical services. The number of employees working for the USSC at any given time ranged from one hundred and fifty to as many as three hundred. Each employee and layer added multiplied the possibility of complications and corruption.[14]

The USSC had ten branch offices located in major metropolitan areas throughout the north, including New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago. These branches coordinated money and supplies coming from the individual soldiers’ aid societies in their respective regions. Each of these branches had their own cadre of office employees, field agents and inspectors. USSC employees sorted incoming supplies stamped with the USSC logo and repacked them (with one type of item in each box for ease of finding the appropriate item when needed by medical personnel) and stored them until hospitals made a request. Mary Livermore’s description of the work done in her Chicago branch gives a glimpse into the size and complexity of the USSC structure. She wrote, “Here we packed and shipped to the hospitals or battle-field 77,660 packages of sanitary supplies, whose cash value was $1,056,192.16. Here were written and mailed letters by the ten thousand, circulars by the hundred thousand, monthly bulletins and reports. Here were planned visits to the aid societies, trips to the army, methods of raising money and supplies, systems of relief for soldiers’ families and white refugees, Homes and Rests for destitute and enfeebled soldiers, and the details of mammoth sanitary fairs.”[15]

The fact that the Sanitary Commission was so large helped it accomplish a great deal during the war but its size also detached it from the very people it depended on. Before the war, most Americans experienced the world in the context of the village. The people they interacted with on a daily basis were friends, family and acquaintances. The war began to erode this intimacy as it necessitated the creation of a larger governmental bureaucratic structure to mobilize the North effectively. Also, daily life was becoming faster paced as cities grew, telegraph lines transmitted information more quickly and trains delivered goods and people to once remote towns and villages. Karen Halttunen explains that the “traditional vertical institutions,” which controlled the cohesion of a community, “could not contain the new complexity of national social life”. Because most nineteenth-century Americans were unaccustomed to such a mammoth federal government and an association as large as the USSC, interaction with these organizations for the average American would have been daunting at the very least. Citizen soldiers and surgeons who experienced the benefits of the USSC began to trust them but civilians withheld complete confidence in this system.[16]

Not only would they have found dealings with the USSC daunting but nineteenth-century Americans were suspicious of interactions in which they did not know all of the parties involved or in which part of the transaction took place away from them. If soldiers returned home and said they never received an item from the USSC, then the conclusion was that there must be corruption in the system. What civilians could not see, they imagined. It was not difficult to envision a sanitary agent setting aside the choicest foods, cordials, and clothes while those who desperately needed the items went without. That a group of men in far off Washington, D.C. had gained women’s confidence to donate goods and then duped them was also possible. Antebellum urbanites were susceptible to the games of the confidence men. Halttunen explains that “the proliferation of moveable wealth . . . and the growing confusion and anonymity of urban living, had made possible for the first time swindles . . . and other confidence games.” Rumors about corruption and profiteering among Commission employees fit into this paradigm.[17]

Regaining the trust of the women of the north took on many forms. The men of the USSC responded with more bureaucracy, believing that more oversight lessened the chance of boxes being lost or misappropriated. They also invited female delegates from the branches to Washington, D.C. for a “Women’s Council.” According to USSC historian Charles Stillé, these councils were held from time to time and “always resulted in perfecting the details of the organization, in stimulating those engaged in work for the soldier to renewed zeal, and in confirming the loyalty of the women of the country to the principles and methods of the Commission.” The related propaganda consisted of statistics and testimonials that often answered negative claims directly. They distributed some of this information in circulars but they also began publishing The Sanitary Commission Bulletin. They explained their purpose for this direct method of communication by saying “Those who furnish the money and the supplies, by which our extensive ministry to the sick and wounded is maintained, have a right to more frequent and full accounts of what becomes of their charity.” [18]

Mr. John F. Seymour, brother of the governor of New York Horatio Seymour, for instance, spent eight days at Gettysburg after the battle and reported that the Sanitary Commission cared for “the suffering multitude [of wounded with] thousands of pounds of bread and meat, clothing, blankets, bandages, beef-tea, condensed milk, liquors in short, everything that human kindness could devise was gathered up by the wide benevolence of this Commission.” B. T. Taylor, a sanitary agent at Chattanooga, Tennessee met the rumors head on: “you hear of the mal-appropriation of your gifts, but never fear . . . your work is everywhere.” He saw it in the roll of linen, pillow, dressing gown, slippers and the dish of fruit he distributed to succor the wounded. From the military hospitals in Nashville, Tennessee, J.P. T. Ingraham, a hospital visitor, assured the readers there was a rigid system of accountability. To counter veterans’ complaint they received no help from the Sanitary Commission, Ingraham explained, that although these very men were clothed head to foot in sanitary clothing and eating food provided by the sanitary, “they seemed to think that because their own good mother’s jar of preserves (which they imagined she had put up) had not been sent straight to them, that neither they nor any one else had ever received any benefit from the Sanitary Commission. It was all a humbug.”[19]

While the USSC regained some of the trust through these endeavors it was never able to fully incorporate all benevolent societies into their network. One problem was that the USSC competed with other national organization requesting women’s goods. In November 1861 the YMCA created the United States Christian Commission (USCC) with the purpose of caring for the spiritual needs of the soldiers. The two agencies saw each other as rivals for women’s homemade goods. The USCC gained the advantage by appealing to the women’s religious sensibilities. The USCC proposed to use monetary contributions to furnish “religious reading and teachings to the soldiers.” USCC delegates also worked for free, whereas the Sanitary Commission paid all of its agents “including the hundreds distributing goods to army hospitals.” Directly targeting the USSC, the Christian Commission assured generous donors, that “the stores they contribute will safely reach the men for whom they are designed.” [20]

Ultimately, the USSC could not overcome the fact that people who were tied to a village-mentality could not trust a far-off faceless entity with homemade goods meant for the benefit of local troops. Women became suspicious of the USSC because it cut them off from personal interaction with the soldiers who benefitted from their gifts. Before the war, female donors could see the needs of the poor in their community and could determine whether society officers properly applied their gifts. Likewise, women personally distributed their goods and believed that through individual contact they could morally encourage the destitute. During war soldiers usually fought away from home; so it was impossible for women to account for the use of their contributions. When the USSC attempted to revamp the whole benevolence system of the country by asking women to channel their supplies through a national agency, it threatened the very essence of communal benevolence. Local societies did not refuse to send their goods to the USSC but they generally met the needs of their own men first and sent goods to the USSC second. The USSC tried to counter this behavior by warning, “If there is a jealous scattering of these resources, a little here and a little there, there will be a dreadful waste, and a melancholy abuse of the well-established principle of unity and economy.” Women ignored these pleas and distributed their gifts according to the priority of obligation: local, state, national.[21]

The USSC may not have convinced women to fully buy into their national approach to aid, but they did accomplish much. Sanitary reform within the military and hospitals improved soldiers’ health and increased their chances of survival after being wounded. The USSC established a Hospital Directory for the numerous military hospitals across the north. Friends and family of the wounded could now locate them more easily. They lobbied for the Army Medical Bill which suspended the seniority system and gave the surgeon general the authority to appoint eight medical inspectors. They encouraged the revamping of the ambulance system in the military and pioneered the use of hospital trains and ships to transport wounded from the battlefields. They established thirty-nine Soldiers Homes to feed and care for troops traveling between camp and home. The USSC Army and Navy Claim Agency helped veterans gain their federal pensions. Perhaps their greatest accomplishment, though, was to professionalize random benevolence and separate the idea of the donor having control of their benevolence. As George Frederickson put it “the Sanitary Commission had instituted a board of experts between the giver and the recipient which would decide on a ‘scientific’ basis how the money could best be spent or the goods distributed.” [22]

The USSC’s legacy lives on in the Red Cross. Although the Red Cross is not a direct descendent, the USSC made it possible for a national organization based on professional benevolence to succeed in the United States. A more nuanced legacy is in donor trust. As we saw, northern women were not comfortable with relinquishing their gifts to a bureaucratic organization no matter how expert the board or scientific their reasoning. Americans today are familiar with bureaucracies, but they continue to question whether the intended needy are receiving donations. When it was revealed that Red Cross officials sent empty Red Cross trucks into the neighborhoods affected by storm Sandy simply to be seen rather than to provide supplies or assistance, this represented the 21st century version of the feared confidence game. Red Cross officials say that “they have never attempted to mislead the public.” That this was revealed by its own employees is a good start to regaining the public’s trust. The USSC emerged during a time of crisis but the broader mission of a national benevolence association endures today.[23]

- [1]Laura Sullivan, Justin Elliott and Jesse Eisinger, “Red Cross ‘Diverted Assets’ During Storms’ Aftermath to Focus on Image,” NPR and ProPublica, October 29, 2014.

- [2] Jeanie Attie, Patriotic Toil: Northern Women and the American Civil War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 128. Instead of admitting inadequacies during this disaster, the Red Cross president and CEO Gail McGovern declared that they had performed well in response to super storm Sandy saying “I think that we are near flawless so far in this operation.” Sullivan, Elliott, Eisigner, Oct 29, 2014.

- [3] Ibid., 39-41; Nancy Scripture Garrison, With Courage and Delicacy: Civil War on the Peninsula, Women and the U.S. Sanitary Commission (Cambridge, MA: DeCapo Press, 1999), 11-12; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 480.

- [4] Attie, Patriotic Toil, 54; Katherine Prescott Wormeley, The Sanitary Commission of The United States Army: A Succinct Narrative of its Works and Purposes, 1972 Arno Press ed. (New York: USSC, 1864), 5.

- [5]Ibid, 5-8.

- [6]Ibid, 8-10; George Worthington Adams, Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 14, 18; Garrison, With Courage and Delicacy, 3, 36, 50-52.

- [7]Attie, Patriotic Toil, 89; Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience as Nurse in the Union Army, Camps, and at the Front, During the War of the Rebellion. (Hartford, CT: A.D. Worthington, 1890), 122.

- [8] Livermore, My Story, 124-7; Garrison, With Courage and Delicacy, 54-55; Adams, Doctors in Blue, 30-31.

- [9] Wormeley, A Succinct Narrative, 12-13.

- [10] McPherson, Battle Cry, 322; Katherine Prescott Wormeley, Christine Thurst Heidorf, ed., 1998 Corner House ed., The Other Side of War: On the Hospital Transports with the Army of the Potomac (Boston: Ticknor, 1889), ii.

- [11] Frederick Law Olmsted, Hospital Transports, A Memoir of the Embarkation of the Sick and Wounded from the Peninsula of Virginia in the Summer of 1862 (Cambridge, MA: University Press, Welch, Bigelow, 1863), xii-x-v, 31-32; Garrison, With Courage and Delicacy, 67, 77,78, 97.

- [12] Wormeley, The Other Side, 112, 117.

- [13] Attie, Patriotic Toil, 130-1; Livermore, My Story 141.

- [14] William Y. Thompson, “The U.S. Sanitary Commission,” Civil War History, 2, no. 2 (June 1956 2): 43-45; Wormeley, A Succinct Narrative, 8.

- [15] Livermore, My Story, 157; Charles J. Stillé, History of the United States Sanitary Commission: Being the General Report of Its Work during the War of the Rebellion (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1866), 178.

- [16] Phillip Shaw Paludan, A People’s Contest: The Union & Civil War, 1861-1865, 2nd Ed. (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1988), 10-11; Karen Halttunen, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982), 12-13.

- [17] Ibid, 18-19.

- [18] Stillé, History, 179; Attie, Patriotic Toil, 133-45; “Introduction,” The Sanitary Commission Bulletin 1, no. 1 (Nov. 1, 1863): 1-2.

- [19] “The Sanitary Commission at Gettysburg,” The Sanitary Commission Bulletin 1, no. 2 (Nov. 15, 1863): 43, 47; “The Hospitals at Nashville,” The Sanitary Commission Bulletin 1, no. 4 (Dec. 15, 1863): 101-2.

- [20] United States Christian Commission: Facts, Principles, and Progress (Philadelphia: C. Sherman, 1863), 9; Attie, Patriotic Toil, 162-3.

- [21] Patricia Richard, Busy Hands: Images of the Family in the Northern Civil War Effort (New York: Fordham University Press, 2003), 184-5; “Introduction,” The Sanitary Commission Bulletin 1, no. 1 (Nov. 1, 1863): 1-2.

- [22] Thompson, “The U.S. Sanitary Commission,” 56; McPherson, Battle Cry, 483; George M. Fredrickson, The Inner Civil War: Northern Intellectuals and the Crisis of the Union (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 106-8,112.

- [23] Sullivan, Elliott, Eisigner, “Red Cross”, Oct 29, 2014; Laura Sullivan, “Red Cross Misstates How Donor’s Dollars are Spent,” NPR and Propublica, December 4, 2014.

If you can read only one book:

Attie, Jeanie. Patriotic Toil: Northern Women and the American Civil War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

Books:

Frederickson, George M. The Inner Civil War: Northern Intellectuals and the Crisis of the Union. New York: Harper and Row, 1965.

Garrison, Nancy Scripture. With Courage and Delicacy Civil War on the Peninsula: Women and The U.S. Sanitary Commission. Cambridge, MA: DeCapo Press, 1999.

Livermore, Mary A. My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Life and Work in Union Hospitals and in the Sanitary Service of the Rebellion. Hartford, CT: A.D. Worthington, 1890.

Maxwell, William Quentin. Lincoln’s Fifth Wheel: The Political History of the United States Sanitary Commission. New York: Longmans, Green, 1956.

Olmsted, Frederick Law. Hospital Transports: A Memoir of the Embarkation of the Sick and Wounded From the Peninsula of Virginia in the Summer of 1862. Cambridge, MA: University Press, Welch, Bigelow, 1863.

Richard, Patricia. Busy Hands: Images of the Family in the Northern Civil War Effort. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003.

Stillé, Charles J. The History of the United States Sanitary Commission: Being the General Report of Its Work during the War of the Rebellion. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1866.

Wormeley, Katharine P. The Sanitary Commission of the United States Army: A Succinct Narrative of its Works and Purposes. New York: USSC, 1864.

———. The Other Side of War: On the Hospital Transports with the Army of the Potomac. Boston: Ticknor, 1889.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives

The New York Public Library just recently completed a three year project of organizing and preserving the records of the USSC. This is the largest and most extensive collection of USSC records in the country. The archives are not available on line but a description of the records they have can be searched on line.