The Vicksburg Campaign

by Michael B. Ballard

Abraham Lincoln, "The war can never be brought to a close until that key (Vicksburg) is in our pocket."

Vicksburg, Mississippi sits on high bluffs overlooking what was once the course of the Mississippi River. The river has moved southwest away from the front of the town now, having been replaced by a canal that connects the Yazoo River with the Mississippi. During the Civil War, however, the river flowed directly in front of the town and was very significant depending on who controlled it—the Union or the Confederacy. For the Confederates, it was the most defensible spot on the river against Union gunboats. The river, starting in Minnesota, ran south though the Midwest into the South and on into the Gulf of Mexico. Just north of Vicksburg, the Mississippi made a sharp hairpin turn, meaning riverboats had to slow down if they were traveling south, and pick up speed if traveling north. Confederate artillery planted along the Vicksburg riverfront made passage perilous for boats going in either direction.

Vicksburg was also important because a rail line ran east to Meridian and beyond connecting the western theater of the war to the eastern. Supplies from the Trans-Mississippi (west Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas) could be taken across the river at Vicksburg and shipped east. Abraham Lincoln commented, “See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key. Here is the Red River which will supply the Confederates with cattle and corn to fee their armies. There are the Arkansas and White Rivers, which can supply cattle and hogs by the thousand. From Vicksburg these supplies can be distributed by rail all over the Confederacy. Then there is that great depot of supplies on the Yazoo. Let us get Vicksburg and all that country is ours. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”[1]

Psychologically and politically, it was vital to the Union war effort to open the Mississippi. Midwesterners felt the river was as much theirs as the Confederates. Finally, Vicksburg was important because both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis decided it was; Lincoln emphasized why it must be taken and Davis why it must be saved. The problem was that neither president nor either war department was sure of how to carry out their Vicksburg plans while maintaining support for other campaigns. The ultimate result would be the longest campaign in the Civil War, May 18, 1862-July 16, 1863.

The initial campaign to capture Vicksburg began with the ascent of Union ships up the river from the Gulf. Commanded by David Farragut, the fleet captured New Orleans and further upriver took Baton Rouge and Natchez without firing a shot. On May 18, 1862, Farragut’s advance ships arrived at Vicksburg, and on May 26, 1862, his vessels began shelling the city.

Later Charles Davis’s fleet came south down the Mississippi, forced the surrender of Memphis and continued downstream to join Farragut in the attempt to take Vicksburg. Their cooperative plans ultimately failed. The main cause was the disruption of Union naval operations by a Confederate ironclad named the C.S.S. Arkansas. The only vessel constituting a Confederate navy on the Mississippi, the Arkansas came down the Yazoo River on July 15, 1862, and brushed aside Union vessels until it reached the Mississippi. Commanded by Isaac Brown, the Confederate ironclad ran a gauntlet of Farragut’s and Davis’s vessels, suffering severe damage, but wreaking as much if not more than it received. It reached the port of Vicksburg with its decks strewn with parts of bodies and awash in blood. But the Arkansas had survived, and its very existence, combined with the daring of its commander, subdued Farragut’s and Davis’s fighting spirit.

The dreadfully hot summer weather, clouds of mosquitoes, and the awareness that all their shelling of Vicksburg had produced no positive results led Farragut and Davis to end the campaign in late summer. Both knew that the navy alone could not force the surrender of Vicksburg. Farragut had been longing to get back to the open sea; the river made him claustrophobic, and as the dry weather lowered water levels, he feared that his heavier ships would not have enough water to go back downstream. He finally received permission to leave, and shortly thereafter, Davis led his contingent back upstream to Helena, Arkansas. The Confederates, including the citizens of Vicksburg, cheered the departure of the enemy navy, but the Federals would be back. There was a dark note; the Arkansas later had to be scuttled north of Baton Rouge due to engine problems. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn, commanding at Vicksburg at the time, sent the ironclad south to help in a failed attempt to recapture Baton Rouge. The Arkansas had not been properly repaired from its earlier action, but the impulsive Van Dorn ignored the danger and sent the boat to its destruction.

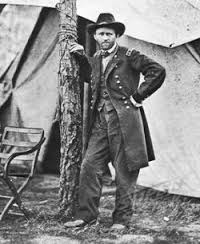

The second phase of the Vicksburg campaign was Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s North Mississippi campaign. Grant, a West Point graduate, had fought in the Mexican War and afterward stayed in the army for several years. However he was stationed for a good part of that time on the west coast, and he sorely missed his family. So he left the army and floundered trying to find a new profession. Nothing worked out for him, but when the war came, so did opportunities for the shabbily dressed diminutive man who would one day command all Union armies. He gained fame relatively quickly after an awkward performance at Belmont, Missouri. He led an army to the capture of forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively. The loss of the forts in northwest Tennessee forced the Confederate army under General Albert Sidney Johnston to abandon Nashville and retreat all the way to Corinth, Mississippi.

The movements of opposing armies led to battle at Shiloh, located on bluffs above the Tennessee River north of Corinth. The April 6-7, 1862 battle produced mixed results for Grant. His army was battered on the first day of the fight, but with the aid of reinforcements, he defeated the Rebels on the second, and the Confederate army retreated to Corinth. Major General Henry Halleck, commanding Union general in the west, blamed Grant for the first day debacle, and Halleck came to Shiloh to lead Union forces in person on a campaign against Corinth. Grant in effect was shelved and almost resigned from the army; his friend, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman (promoted from Brigadier General after a good performance at Shiloh), talked Grant into staying put.

Halleck took Corinth, which had been evacuated by the Confederates, and was eventually called to Washington to take command of all Union forces, and Grant regained his command. His performance was poor at the Battle of Iuka, September 19, 1862, and he was not even present to participate in the Battle of Corinth, October 2-3, 1862 as Confederates tried to retake the town. The battles, both in northeast Mississippi, resulted in Union victories and secured Union control along the Mississippi and Tennessee state line from Memphis to Iuka. This gave Grant the opportunity to invade North Mississippi, his first attempt to capture Vicksburg.

Grant planned to take his army down the Mississippi Central Railroad from West Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi, the state capitol, and then turn west along the Southern Railroad of Mississippi to attack Vicksburg. Having learned that a political general (former U. S. Congressman), Major General John McClernand had been to Washington to lobby for his own command to capture Vicksburg, Grant hurriedly sent William Sherman, at the time commanding the Memphis area, south with a fleet to attack Vicksburg from the north. Grant, meanwhile would continue south along the Mississippi Central and turn toward Vicksburg to hopefully join forces with Sherman and force the surrender of the city.

As Grant moved south against the Confederate army, now led by Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton, a Pennsylvania native married to a Virginia woman, his progress was slowed by the retreating Confederates who burned bridges over rivers. The rugged North Mississippi terrain, wet weather, and scant supplies available in the countryside added to Grant’s problems. An attempt to flank Pemberton’s left with a force sent from Helena failed. The key blow to Grant’s operation was delivered by Earl Van Dorn.

Van Dorn had been commanding in the field while Pemberton, who preferred staff work to combat, spent most of his time at his Jackson headquarters. The Confederates continued to retreat south until they reached the town of Grenada. There plans were made to send Van Dorn on a raid against Grant’s supply depot at Holly Springs, well north of Grenada and a long way from Grant’s main force. Grant should have anticipated an attack as his main supply line stretched further and further as he moved south. He did have patrols along the railroad, but an enemy approach through the countryside away from the railroad would be difficult to detect.

On December 20, 1862, Van Dorn’s cavalry struck the Holly Springs supply depot and captured the town before burning tons of supplies intended for Grant’s army. Van Dorn put a guard around a home where he thought Mrs. Grant was staying; actually she had gone south to Oxford to see her husband. Grant had no choice but retreat, and his army marched north back to Tennessee. Meanwhile Sherman carried out his attacks from the Yazoo River against strong Confederate defenses along the Walnut Hills north of Vicksburg. After several days of hard fighting, Sherman’s losses mounted in what was called the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, a small stream that would from and back into the Yazoo along lowland in front of the Walnut Hills bluffs. Sherman, by now aware of Grant’s retreat, gave up and moved back out to the Mississippi. John McClernand arrived downriver and due to seniority took command of Sherman’s force. Leading an expedition into Arkansas along the White River he captured Fort Hindman, a key Confederate outpost for protecting the transportation of supplies from Arkansas to the Mississippi. The victory was a consolation for Grant’s and Sherman’s failures. Now Grant had to decide what to do next. He was buoyed by word from Washington that he had command over McClernand and any troops McClernand might have raised (most of those troops had gone downriver with Sherman earlier). McClernand still thought he had an independent command before finally realizing that official Washington had stabbed him in the back. Grant also felt reassured by the fact that he was not removed from command due to his recent failures. Now he could concentrate on what to do next to capture Vicksburg.

From January-April, 1863, Grant tried several routes to get at Vicksburg and all failed. One of his plans included sending troops via Louisiana bayous south to the Red River which emptied into the Mississippi well below Vicksburg. The Lake Providence gambit was an attempt to carry out the plan but inadequate water levels and passages doomed it to failure. His most notable operation was the Yazoo Pass expedition. He intended sending gunboats and transports into the Tallahatchie River northwest of Greenwood, Mississippi, where the Tallahatchie merged with the Yalobusha River to form the Yazoo, which flowed south to the Mississippi. This was the same river from which Sherman had launched his assaults along Chickasaw Bayou. Sherman had gone up the Yazoo directly from the Mississippi; this time the Union forces would come from the opposite direction.

The campaign began with engineers blowing a hole in a levee to flood a waterway called Yazoo Pass with waters pouring in from the Mississippi. From that point, the Union expedition followed the Coldwater River into the Tallahatchie. Things went smoothly until the gunboats got close to Greenwood. There they ran into the guns of Fort Pemberton, an obstacle built by the Confederates near the confluence of the Tallahatchie and the Yalobusha rivers to stop the Union operation. After several weeks of frustration, Grant scrapped the plan, which had lasted from February 23 to April 15. Confederate resistance was too strong. Commanded by Major General William Wing Loring, the defenders of Fort Pemberton refused to budge.

Another attempt to get a foothold north of Vicksburg, led by Acting Rear Admiral David Porter, commanding the Union navy, also failed. (The “Acting” part of Porter’s rank would be removed after the fall of Vicksburg.) Porter went up the Yazoo from the Mississippi, then turned into a bayou. In what was termed the Steele’s Bayou expedition, April 14-27, Porter almost got trapped in streams too narrow to allow his large gunboats to keep going. He finally had to back the boats out of trouble, receiving some infantry help from Sherman to fight off the Confederates. John Pemberton did not send reinforcements; if he had done so, his troops might well have captured the gunboats, but his slow reaction to the situation doomed a golden opportunity.

Grant now decided to implement a plan that had been discussed for some time. He would send his army moving down the west side of the Mississippi south through Louisiana lowlands and cross the river well below Vicksburg. Once they began to make progress, he would have David Porter send gunboats and transports downriver past the Vicksburg batteries. Porter agreed to the plan, and he sent a fleet at night, equiping the transports with cotton bales strapped to the sides of the boats to protect them from Rebel shells. His flotilla successfully ran the gauntlet, losing only one vessel. The guns on the Vicksburg bluffs did less damage than expected, because Confederate gunners could not depress their gun barrels sufficiently to hit Porter’s vessels traveling close to the east bank of the river. A second run past the batteries was also successful.

Grant now focused on crossing his troops from Louisiana into Mississippi at a town called Grand Gulf. Grand Gulf, however, was strongly fortified and the strong resistance to Porter’s fleet during a fight on April 29 forced Grant to look further downstream. He found a place called Bruinsburg, a former river landing site long since abandoned. The night of April 30, 1863, Porter’s transports began ferrying Union troops across the river into Mississippi. Up to that point in American history, this was the largest amphibious operation ever.

John McClernand’s XIII corps led the way, followed by Major General James McPherson’s XVII. Grant and McClernand continued to detest each other, but it is worth noting that Grant had McClernand, who fully supported the operation, lead the way. McClernand’s corps also covered the army’s left flank, the flank most exposed to Confederate attack, during the forthcoming march inland. Sherman later joined the army with his XV Corps after a demonstration north of Vicksburg to hold John Pemberton’s attention. Sherman did not believe in the campaign, and his hesitancy likely accounts for Grant having Sherman come up in the rear.

Meanwhile, John Pemberton’s best general, Major General John Stevens Bowen, who commanded at Grand Gulf, realized what Grant was doing and begged Pemberton for reinforcements. Pemberton, by now thoroughly confused as to Grant’s intentions, all the more so due to a cavalry raid by Colonel Benjamin Grierson through the heart of Mississippi, acted slowly, and Bowen wound up facing an enemy force of around 24,000, three times Bowen’s 8,000, at the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1. As Grant’s army moved inland, it took two roads leading from Bruinsburg to Port Gibson, forcing Bowen to fight a two front battle. The terrain was made up of high ridges and deep valleys which gave Bowen problems in coordinating the fighting of his two wings. Grant’s army found a road that connected the two roads inland, and thus facilitated its fighting ability. After a day long battle, during which the rugged geography and resulting low visibility slowed the Union advance, Bowen had no choice but to withdraw to Port Gibson, abandon Grand Gulf, and head north toward Vicksburg. He lost around 800, less than Grant’s 900. His men had fought well, but Pemberton’s delay in sending reinforcements, and his inability to grasp the meaning of Grant’s plan doomed Bowen’s ability to push Grant back to the Mississippi River. Grant now had a strong foothold in Mississippi and could finally set his sights on an inland approach to Vicksburg.

After the victory at Port Gibson, Grant moved north and northeast toward the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. James McPherson’s Corps marched to the right of McClernand and near Raymond on May 12 met a Confederate brigade led by Brigadier General John Gregg. Gregg did not realized he faced an entire Union corps, and he attacked. His outnumbered troops fought well, but the numerical difference soon forced him to retreat toward Jackson, the state capital. Gregg losses totaled slightly over 800, more than twice McPherson’s casualties. Around that time, Grant learned that General Joseph E. Johnston had arrived in Jackson with reinforcements for Pemberton from the east. Grant decided he must chase Johnston away, before he could turn his attention toward Pemberton.

Johnston did not require much chasing. He decided that he was too late to do any good, so he abandoned Jackson and moved northwest to the town of Canton. Grant rode with Sherman, who had finally arrived with his corps and attacked Jackson from the south. McPherson marched north and then turned east to hit the capital from the west. Johnston had left behind only a token force, which was easily overwhelmed on May 14. Grant lost less than 300 men while the Confederate token force left behind by Johnston suffered 850 casualties, many of them captured.

Grant left Sherman in Jackson to destroy clothing factories and anything else that might be of use to the Confederate army. He then turned west toward Vicksburg. One of his spies intercepted a message from Johnston to Pemberton in which Johnston ordered Pemberton to march toward Clinton (between Jackson and Vicksburg). Pemberton did not know that Johnston was moving toward Canton, but Grant knew that Pemberton would likely march to join Johnston. Grant hurried McPherson and McClernand toward Vicksburg to attack Pemberton before he could merge his force with Johnston’s. While the Battle of Jackson was being fought, McClernand’s corps had been west of Raymond to keep an eye on Pemberton who had three divisions in the area where the railroad crossed the Big Black River.

Pemberton had led his three divisions toward the Big Black River to meet Grant, though just what he would do remained unknown, even to him. He met with his commanders, major generals John Bowen, William Loring, and Carter Stevenson, in the area of Edwards, a small community just east of the Big Black Bridge. After some discussion, Pemberton decided to ignore Johnston’s order; he feared marching toward Johnston would make Vicksburg vulnerable to Grant. Pemberton had left two divisions behind to protect the town, but they would not be sufficient to stop Grant. Pemberton decided to move toward Raymond to break Grant’s supply line which connected with the Union supply depot at Grand Gulf. Heavily laden wagons of food and ammunition had followed Grant inland, but by this time, worried about their vulnerability, and no doubt remembering what had happened at Holly Springs, Grant had cut off the supply line.

Pemberton moved toward Raymond and was held up by the flooded Bakers Creek that flowed from the northeast to the southwest across his path. By May 15, his army was strung out from the northwest to the southeast with Stevenson on the left, Bowen in the middle, and Loring on the right. He received a second message from Johnston, again ordering him to come to Clinton. Johnston still was in Canton, so what he had in mind is a mystery. He had made no move to the southwest, which he would have had to do to meet Pemberton at Clinton. The truth was that Johnston was ready to give Vicksburg to Grant, join forces with Pemberton, and fight in open country without being tied down to Vicksburg. Pemberton had been ordered to hold Vicksburg and Port Hudson (a river stronghold just north of Baton Rouge), at all costs. He would not abandon Vicksburg, but he did decide to try to turn his army northeast as Johnston had ordered. Pemberton assumed the joint Confederate force would attack Grant before the Yankees would reach Vicksburg.

On the morning of May 16, Pemberton tried to put his army into reverse, which was a complicated maneuver since his wagon trains were on the far left end of his army’s line. For Carter Stevenson’s division to about face and move toward the northeast and then east would not be easy. As things turned out, it did not matter. The proximity of enemy campfires the night of May 15 should have alerted Pemberton that he could not move from his position before he would be forced into a fight. The fight came when McPherson’s corps charged Stevenson’s division; many of Stevenson’s troops broke and ran. Some brigades held as long as they could, but soon Stevenson’s position was in a shambles.

Pemberton sent word to Bowen and Loring that they must send reinforcements, but neither general wanted to weaken their positions, for they both had Yankee forces in front of them—part of McPherson’s corps and all of McClernand’s. Bowen recognized the danger if Stevenson’s flank evaporated, and he did lead his division in a charge that penetrated the center of Grant’s line. Bowen actually stood on the verge of victory until overwhelmed by Union reinforcements. Pemberton’s appeal to Loring to send help to Bowen fell on deaf ears. Pemberton finally called for a retreat back to the Big Black River. Loring fought a holding action against McClernand while Bowen’s division and what was left of Stevenson’s re-crossed Bakers Creek. Loring’s division ultimately got cut off from the rest of the Confederate army, and he led his men south, east, and then north, where he joined with Johnston’s force at Canton. At Champion Hill, the key battle of the campaign, Grant lost 2,500 while Pemberton suffered just under 4,000 casualties.

Pemberton, unaware that Loring was no longer on the scene had his army dig in on both sides of the Big Black River to give Loring time to rejoin the army. Loring of course never showed up, and on May 17, McClernand attacked the worn out Confederates, driving them pell-mell across the Big Black River and onto the road back into Vicksburg. Union losses were just under 300, while the Confederates suffered 1,750 men, including some captured and some who drowned trying to swim across the Big Black River. Pemberton might have turned his army north to avoid being penned up in Vicksburg, but he still had two divisions there, commanded by major generals M. L. Smith and John Forney. Pemberton also had been ordered by President Davis to hold the town, and he meant to do just that, despite another message from Johnston to abandon Vicksburg.

Grant’s army followed up their victories by moving toward Vicksburg—McClernand on the left, McPherson in the center, and Sherman on the right. On May 19 and again on May 22, Grant ordered attacks on the Vicksburg defenses, and his army was beaten back with heavy losses. The ridges fortified by Pemberton’s engineers provided excellent defensive positions, especially since the approaches required Union attackers in many spots to charge uphill from deep ravines. Grant settled for a siege, and, counting the first two assaults, the fighting continued for 47 days until Pemberton ran low on supplies and realized that Johnston, with his so-called Army of Relief, was not going to do anything. Grant put Sherman in charge of a strong rear-guard to make sure Johnston did not try to attack the Federal rear. While Pemberton received no reinforcements, additional Union soldiers rode transports down the Mississippi, beefing up Grant’s army to around 80,000. Pemberton surrendered on July 4, 1863, one day after Robert E. Lee’s loss at Gettysburg. Siege casualties included 4,800 for Grant and 3,200 for Pemberton. The key figure of course was the surrender of Pemberton’s army, estimated to have been around 29,000 men.

To cement the victory, Grant wanted to chase Johnston away. Even though Johnston had shown no inclination to fight, Grant did not want his presence close to Vicksburg to continue. So Grant sent Sherman with a strong force which chased Johnston to Jackson. Johnston resisted for a time, and Sherman used siege tactics to keep the Confederates from attacking. From July 10-17, Yankees and Rebels fired at each other, Sherman suffering 1,000 losses and Johnston 1,350. Finally, Johnston, who had little affinity for attacking, abandoned Jackson and his army fed into the woodlands of east Mississippi. Sherman, who had problems providing his men with decent water, realized that his soldiers were already drained from the hot weather and their service at Vicksburg. He decided not to pursue the retreating Rebels. Both Sherman and Grant had decided that Johnston was no longer a threat. In fact, he had never been one.

The results of the Vicksburg campaign included the capture of a Confederate army that was never to fight again as an army. Grant’s forces captured 172 cannon, 38,000 artillery munitions of various kinds, 58,000 pounds of black powder, 50,000 rifles, 600,000 rounds of rifle ammunition, 350,000 percussion caps, 5,000 bushels of peas, 51,000 pounds of rice, 92,000 pounds of sugar, 721 rations of flour, and 428,000 pounds of salt. The Union had complete control of the Mississippi when Port Hudson fell on July 9. The Trans Mississippi region (all Confederate territory west of the Mississippi) was cut off from the rest of the Confederacy, though smuggling efforts continued.

Perhaps just as importantly Confederate morale, especially in the Western Theater of the war, left a dark cloud of despair over Rebel soldiers and civilians. Robert E. Lee’s army would fight on for two more years, but the loss of Vicksburg, an army, and control of the Mississippi proved to be a serious blow from which the Confederacy never recovered.

- [1] David Dixon Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War (New York: D. Appleton, 1885), 95-6.

If you can read only one book:

Ballard, Michael B. Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Books:

Ballard, Michael B. Pemberton: The General Who Lost Vicksburg. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1991 (originally published as Pemberton: A Biography).

———. Grant at Vicksburg: The General and the Siege. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2013.

Bearss, Edwin Cole. The Vicksburg Campaign. 3 vols. Seattle WA: Morningside Press, 1985-1986.

Winschel, Terrence J. & William L. Shea. Vicksburg is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.