Washington: Capital of the Union

by Kenneth J. Winkle

Washington, DC, was the most strategic and vulnerable city in the Union during the Civil War. Sandwiched between the Confederate state of Virginia to the west and the border slave state of Maryland to the east, Washington sat astride the Civil War’s most critical and active military front, the Eastern Theater. The Union army used the city to mobilize and supply the Army of the Potomac, defend the eastern seaboard, and launch military thrusts toward Richmond. Believing that the loss of the Union’s capital would lead to immediate defeat, the Confederacy targeted Washington throughout the war. From the First Battle of Bull Run onward, Confederate armies repeatedly threatened Washington as part of General Robert E. Lee’s strategy of “taking the war to the enemy.” The tripling of the city’s population during the war produced a public health crisis that promoted epidemic diseases, including smallpox. Turning Washington into the central site of medical treatment for sick and wounded soldiers in the Eastern Theater, the army established more than one hundred military hospitals in the capital, innovating new approaches to medical care and hospital design. Forty thousand fugitive slaves, primarily from Virginia and Maryland, sought refuge in the national capital. Through its proximity to the front, Washington assumed the role of “grand depot of supplies” for the Eastern Theater. The war also flooded the capital with hundreds of thousands of sick and wounded soldiers. President Lincoln and his wife Mary visited the hospitals frequently, extending both personal and symbolic comfort to the wounded. Outside of the hospitals, Washington remained an unsanitary and disease-ridden city. In the absence of modern water and sewage systems, infectious diseases were endemic in antebellum Washington. The human toll was heartrending and included the Lincolns’ 11-year-old son Willie, who succumbed to typhoid fever early in 1862. Lincoln himself nearly died from smallpox in the weeks that followed his Gettysburg Address. Overall, the Civil War took an extraordinary toll on Washington’s permanent and temporary residents, but their struggles and sacrifices helped to win the war, preserve the Union, end slavery, and transform the city into a larger and more modern national capital.

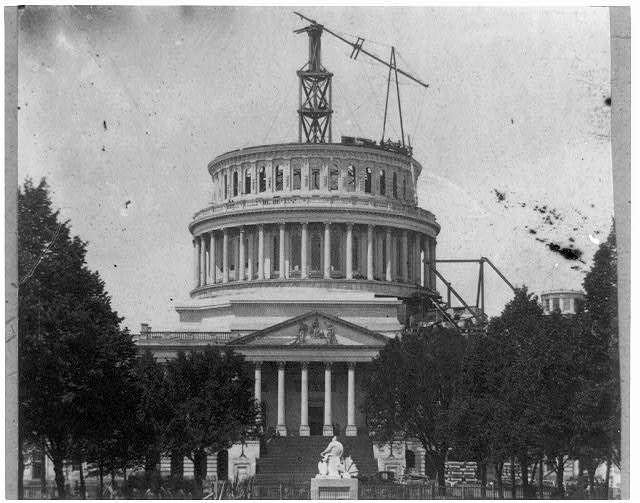

Capitol Dome Construction 1861

Courtesy of: The Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a01225/

Washington, DC, was the most strategic and vulnerable city in the Union during the Civil War. Sandwiched between the Confederate state of Virginia to the west and the border slave state of Maryland to the east, Washington sat astride the Civil War’s most critical and active military front, the Eastern Theater. The Union army used the city to mobilize and supply the Army of the Potomac, defend the eastern seaboard, and launch military thrusts toward Richmond. Believing that the loss of the Union’s capital would lead to immediate defeat, the Confederacy targeted Washington throughout the war. From the First Battle of Bull Run onward, Confederate armies repeatedly threatened Washington as part of General Robert E. Lee’s strategy of taking the war to the enemy. Lee’s advances into Maryland in 1862 and Pennsylvania in 1863 were primarily designed to threaten Washington, and in July 1864 Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early launched a direct attack on the city, which was repulsed. Throughout the war, the Lincoln administration took unprecedented actions to secure the capital against Confederate attack and suppress internal subversion at the hands of secessionist sympathizers.

Meanwhile, the indirect impact of the war posed novel challenges as well as opportunities. The tripling of the city’s population produced a public health crisis that promoted epidemic diseases, including smallpox. Turning Washington into the central site of medical treatment for sick and wounded soldiers in the Eastern Theater, the army established more than one hundred military hospitals in the capital, innovating new approaches to medical care and hospital design. Forty thousand fugitive slaves, primarily from Virginia and Maryland, sought refuge in the national capital. The army created a series of contraband camps, as they were known, to house them, which culminated in the creation of Arlington Freedman’s Village on the confiscated Lee estate across the Potomac River in Virginia. Republicans in Congress seized upon the wartime emergency to reform Washington, freeing the District of Columbia’s three thousand slaves in April 1862 and extending basic civil rights to African Americans. Assuming political control of the city, Republicans—under the guise of the Unconditional Union Party—enacted a long-overdue program of urban reform. Overall, the wartime emergency helped to transform Washington into a larger and more modern city that was better prepared to serve as the seat of government for the reunited nation.

In 1860, Washington was the twelfth-largest city in the nation, with a population of 61,000. As an artificial city, Washington’s primary function was to host the seat of government, and its economy was service-centered rather than industrial or commercial in orientation. One of its largest business sectors was hosting members of Congress, executive officers, and government clerks in the hotels, boarding houses, and restaurants that lined Pennsylvania Avenue and clustered around Capitol Hill. Originally a mainstay of the capital’s economy, slavery had declined steadily in the three decades before the Civil War. As the Potomac region’s agricultural base shifted from cotton to wheat, Washington became a major entrepot in the interregional slave trade that sent slaves from the Upper South to the expanding cotton belt of the Southwest, focused on the emerging slave markets in New Orleans. In 1800, about one-fourth of Washington’s residents were slaves, but that proportion fell to twelve percent by 1830. The Compromise of 1850, which outlawed the slave trade in the District of Columbia, accelerated the decline of slavery in Washington. In 1860, slaves represented three percent of the population. Meanwhile, the city’s free African American community expanded dramatically to fifteen percent and represented the second-largest in the nation behind Baltimore’s.

Slaves and free African Americans performed the bulk of the city’s physical labor, most of it menial in character. Two-thirds of the city’s slaves were females who worked primarily as domestic servants, preparing and serving meals, sewing and washing clothing, tending children, and working as chambermaids and body servants in the homes of their owners. Some male servants performed “indoor work” as cooks and waiters, but most engaged in “outdoor work” as coachmen, teamsters, stable hands, and gardeners. A substantial number were “hired” or “rented” out as skilled craftsmen, including carpenters, blacksmiths, masons, and painters. As slavery declined, white families began hiring free African Americans as live-in servants, primarily as housemaids, cooks, and waiters. Five-sixths of free African Americans, however, maintained independent households but were occupationally segregated into a narrow range of menial pursuits as laborers, waiters, hackmen, waggoneers, and porters. One-third of free African American men were laborers, and four-fifths of African American women were servants or cooks. Washington’s Irish community suffered similar kinds of economic barriers as African Americans. By 1860, more than one-fourth of household heads were immigrants, 60 percent of them Irish. Their primary economic role was providing unskilled labor for the growing city. Four-fifths of all white laborers were Irish, and their arrival freed most native-born whites from manual labor.

Antebellum Washington was a predominantly southern city in population, heritage, and sympathies. Probably nine-tenths of its native-born white residents were southern by birth or ancestry, and their political leaders had expressed virulent antagonism toward the Republican Party and its antislavery orientation from its very inception in 1854. Lincoln’s election provoked a series of riots and arsons that were tolerated and even abetted by the Democratically controlled police. On election night, a militia composed of southern sympathizers stormed and ransacked the Republican Party’s headquarters in Washington. During the secession crisis, the federal government’s hold on Washington was so precarious that many of Lincoln’s supporters feared that he would never reach the city. With disloyalty rampant, assassination plots brewing, and coup attempts in the offing, Lincoln’s friends persuaded the president elect to enter the capital in the middle of the night, secretly and in disguise. Accompanied by Chicago detective Allan Pinkerton and his personal bodyguard, Lincoln rode in a windowless boxcar through Baltimore and arrived in Washington under cover of darkness. After reaching the White House, the new president looked out the window and saw a Confederate flag waving just across the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia. Ashamed of this inauspicious beginning to his presidency, Lincoln quickly went on the offensive to secure the city, transform it into a base of military operations against the Confederacy, make it a symbol of a resilient and enduring Union and, in short, turn it into a truly national capital.

On April 1861, a mob confronted Union troops as they passed through Baltimore, Maryland, on their way to defend Washington. A riot broke out in which four Union soldiers were killed and thirty-six wounded. Twelve civilian rioters died, and an unknown number were wounded. Southern sympathizers tore up railroad tracks, destroyed railroad bridges, and tore down telegraph wires along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad that represented Washington’s primary transportation and communication connection to Baltimore and northern cities. As the capital city sat isolated and nearly defenseless for over a week, Lincoln frequently stood at the window of his White House office watching for troops to arrive from the North. To restore and protect the railroad line between Washington and Baltimore, Lincoln authorized his first suspension of habeas corpus. This episode provoked Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney’s Merryman decision, which granted a writ of habeas corpus to John Merryman, a Marylander who had been arrested as a Confederate sympathizer. Lincoln ignored Taney’s writ, upheld his suspension of habeas corpus, and maintained a strong military presence in Maryland throughout the war. Ultimately, Lincoln expanded his suspension of habeas corpus to encompass the entire nation.

Within the capital itself, Lincoln embarked on a comprehensive program of security measures and government reforms that he dubbed “cleaning the devil out of Washington.” [1] In August 1861, his administration arrested the city’s Democratic mayor, James Berret, as a security risk because of his alleged Confederate sympathies and associations. Imprisoned on an island in New York Harbor, Berret agreed to resign as mayor in exchange for his release. He stayed in New York City for the rest of the war. The deposed mayor was succeeded by Richard Wallach, a former Republican, a leader of the Unconditional Union Party, and an enthusiastic supporter of the Union war effort. To restore civil order in Washington, Congress reformed the corrupt and politically charged police force. During the 1850s, Democratic mayors had allowed the police to bolster their own party at the expense of Republicans through patronage and a long series of election day riots, benefit financially from arbitrary fines and fees, and abet slavery and racism through draconian enforcement of the city’s slave code and the black code that governed free African Americans. Upon the outbreak of war, Washington’s police force was rife with secessionism, and many policemen defected to the Confederacy. In August 1861, Congress consolidated the police forces of Washington, Georgetown, and Washington County into the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department, along the model that New York City had adopted in 1845. To buffer the department from local political influence, the Board of Police comprised five commissioners nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Police officers took an oath of loyalty to the Union, were prevented from intervening in elections, and could not accept fines, fees, or other emoluments. The police stopped apprehending fugitive slaves as criminals under the Fugitive Slave Law. During the war, the newly reformed police force made 70,000 arrests. The government erected a new guardhouse to accommodate prisoners and converted a building across the street from the Capitol into the Old Capitol Prison, which could hold 2,700 prisoners of war and prisoners of state or civilians.

At the same time, a federal detective agency, established by Allan Pinkerton, exposed genuine breeches of government security and sent several infamous Confederate spies, including Rose O’Neal Greenhow and Maria “Belle” Boyd, to the Old Capital Prison. To enforce martial law and suppress anti-government subversion and dissent, the Union army established an extensive provost guard that arbitrarily arrested thousands of suspected Confederate sympathizers. Lincoln empowered the provost guard to enforce both military and civil law in Washington and to arrest civilians upon suspicion of disloyalty and subversion. During the war, almost three hundred Washington residents endured such arbitrary arrests and spent time in the Old Capitol Prison without benefit of warrant, legal representation, or trial. The army’s provost guard gradually expanded to become national in scope. To ensure loyalty within the federal and municipal governments in Washington, Congress established a series of loyalty oaths that led to wholesale resignations and dismissals among Confederate sympathizers. The House of Representatives created a committee, chaired by Republican John Fox Potter of Wisconsin, to monitor the loyalty of federal employees. The Potter Committee identified 320 government employees that they considered disloyal, often on the basis of hearsay evidence and past partisan associations. By the end of the war, loyalty oaths, detective bureaus, and arbitrary arrests had become routine wartime security features throughout the Union.

The Civil War not only expanded the scope and power of the federal government but also the size of its capital. Between 1860 and 1870, Washington’s permanent population doubled, representing the greatest decennial growth in its entire history. During the war, the city filled with people and at times swelled to 200,000. As soon as the Maryland bottleneck reopened in May 1861, troops, weapons, horses, and supplies began pouring into Washington. Almost overnight, twenty thousand men enveloped a city whose peacetime population was only sixty thousand. The first accommodations were makeshift. Soldiers encamped in the East Room of the White House (the first sentence of John Hay’s diary was simply “The White House is turned into barracks”) and later its lawn, the Capitol, Georgetown College, Columbian College (now George Washington University), the Washington Arsenal, churches, and a profusion of buildings that the government rented for the purpose. [2] Soon, a sea of army tents surrounded the Capitol for a radius of three miles. The Capitol itself accommodated seven thousand troops at a time, filling the Senate and House chambers, galleries, committee rooms, and hallways. Later, whole armies, composed of volunteers and draftees from across the North, moved continually through the city, up to 140,000 at a time. By the end of the war, the Quartermaster’s Department had erected more than four hundred new buildings and structures to accommodate the army and the expanded federal government.

Through its proximity to the front, Washington became the Army of the Potomac’s primary supplier of arms, ammunition, horses and provisions, which flooded into the capital by railroad from the north. The army demanded horses by the thousands as mounts for its cavalry, along with mules to pull its vast fleet of wagons and ambulances. Just weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter, the government corral in Washington stabled two thousand horses. Soon, herds of five hundred were arriving regularly from across the North, and the mammoth Government Stock Depot corralled 10,642 horses and 2,718 mules, with 1,200 wagons and 133 ambulances on hand. South of the White House, the mall around the unfinished Washington Monument contained a pasture for grazing cattle and slaughterhouses to feed the armies that defended the city. To stockpile the tons of provisions that arrived in Washington each day, the government created a Subsistence Depot consisting of twenty huge warehouses along the city’s Potomac wharves. To supply the Army of the Potomac, the depot stored three million military rations, including 18,000 barrels of flour, 9,000 barrels of salted beef and 3,000 of salted pork, 500,000 pounds of coffee, 500,000 pounds of sugar, and 1,500,000 pounds of hard bread, along with tons of candles, soap, and ice. Washington also housed the largest arsenal in the Union at what is now Ft. McNair, as well as the U.S. Navy Yard and the Baltimore and Ohio railway depot, which moved thousands of troops into and through the city daily.

All around the White House sat omnipresent reminders of the mammoth war effort and Lincoln’s role as its commander-in-chief. Not only the War Department but also the Navy Department, the Union Army Headquarters, the Army of the Potomac Headquarters, and the Headquarters Defenses of Washington all sprang up within walking distance of the White House. Lincoln frequented them personally, making the rounds in his effort to oversee a coordinated war effort. He not only worked with Congress and the Union army to ensure the security of the capital but turned its proximity to the war to his own advantage. As commander-in-chief, he developed a hands-on approach to military strategy, making thirteen trips to visit his commanders in the field in northern Virginia. On these visits to the front, Lincoln spent up to a week at a time advising his generals in person, raising morale by reviewing and rallying the troops, visiting with the wounded, and emphasizing his practical and symbolic engagement with the armies as a visible proponent of national resolve. On one occasion, he gained personal insight into the sacrifices the war entailed by witnessing firsthand the burial of the dead on the battlefield. During his presidency, Lincoln spent a total of 58 days away from Washington on these visits to his generals and their troops. The headquarters of the War Department sat alongside the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue. There, Lincoln spent days on end poring over reports from the field. He soon mastered the art of coordinating a modern army via the recently invented telegraph. During major engagements, he spent many a night sitting in the telegraph office waiting for the latest dispatches to arrive.

Lee’s summer offensives of 1862 and 1863, which culminated in the pivotal battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, were primarily designed to threaten Washington, encourage southern sympathizers in the North, and challenge the Lincoln administration’s authority to govern. At Lee’s behest, Stonewall Jackson’s army could emerge from the Shenandoah Valley and advance on Washington whenever the Army of the Potomac neared Richmond. In response, Lincoln insisted on maintaining an army of 15,000 to 50,000 men in and around the capital, often to the dismay of his generals who coveted these reinforcements. (Lincoln reasoned that “I must have troops to defend this Capital.”) [3] During the winter of 1861-62, after the First Battle of Bull Run, work began on a 37-mile ring of fortifications around the city. This defensive system eventually boasted 68 forts connected by twenty miles of trenches and 800 cannons clustered in 93 artillery positions. By itself, each fort was undermanned, garrisoned in one instance by a single sergeant and two sentries. As Chief Engineer John Gross Barnard explained, “the fronts not attacked may contribute the larger portion of their garrisons to the support of those threatened.” [4] As long as Washington faced attack from only one direction, the defenses would hold. During the summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early led a raid on the city that tested its defenses and rallied its residents, including Lincoln. When Early’s army penetrated to within five miles of the White House, Lincoln thrust his own safety aside and personally rushed to Fort Stevens, where Union forces successfully repulsed the Confederate army. By the end of the war, Washington was the most heavily defended city on earth.

The war flooded the capital with hundreds of thousands of sick and wounded soldiers. Every campaign and major battle in the Eastern Theater poured thousands of casualties into Washington for emergency medical treatment. At the beginning of the war, the city had a single general hospital that admitted fewer than two hundred patients a year, and the entire U.S. army boasted only thirty surgeons. During the first year of the war alone, the army treated 56,000 sick and wounded soldiers in Washington. At the peak of the fighting in June 1864, during the horrific Battle of Cold Harbor in Virginia, the capital accommodated 17,717 patients in its military hospitals on a single day. To accomplish that feat, the government hastily created more than one hundred military hospitals and recruited thousands of surgeons and nurses to staff them. A series of medical crises prompted experimentation with new hospital designs, novel approaches to transporting the wounded by railroad and steamboat, and the recruitment of female nurses, mostly volunteers, on a massive scale.

At the beginning of the war, makeshift hospitals, including hotels, churches, the Capitol Building, and hundreds of private homes, ministered to the sick and wounded. Midway through the war, more sanitary, open-air hospitals, about thirty of them, each with ten or twelve wards housing 600 patients, dotted the city. Volunteers from across the North, including Clarissa “Clara” Harlowe Barton, Dorothea Lynde Dix, Louisa May Alcott, and Walt Whitman, spent their days tending to the wounded. (Whitman alone ministered to tens of thousands of wounded men, northerners and southerners alike.) Soldiers who survived their wounds were transported by train to Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City to convalesce. Those who died were buried in pine coffins, at a cost of $4.99, in the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery. When it filled up in 1863, the government began burying the fallen on Robert E. Lee’s estate across the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia. Coffins now moved solemnly, by the hundreds, across the Long Bridge and over the Potomac to what became Arlington National Cemetery, perhaps the nation’s greatest symbol of military honor and sacrifice.

President Lincoln and his wife Mary visited the hospitals frequently, extending both personal and symbolic comfort to the wounded. Abraham Lincoln, for example, spent part of July 4, 1862, riding with a train of ambulances carrying wounded soldiers from the Peninsular Campaign to a makeshift hospital at the Soldiers Home and two years later visited three hospitals, shaking hands with a thousand soldiers in a single day. While visiting one of the hospitals, he watched the amputation of a wounded soldier’s arm. Former patients and their families often visited Lincoln at the White House, to receive his thanks and to inspire him in return. When the “One-Legged Brigade” from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital assembled outside the White House, Lincoln called them “orators,” whose very appearance spoke louder than any words. [5] The day before he left for Gettysburg, Lincoln watched 2,500 members of the Invalid Corps pass by the White House. Mary Lincoln not only visited the wounded but raised funds to help support the hospitals. She provided flower from the White House Conservatory, fresh fruit to ward off scurvy, and turkeys and chickens for Christmas dinners, which she personally served to the soldiers. On her visits to the hospitals, she consoled the men, read to them, copied letters home, and attended musical performances and literary readings. Outside of the hospitals, Washington remained an unsanitary and disease-ridden city. In the absence of modern water and sewage systems, infectious diseases were endemic in antebellum Washington. The tripling of the population during wartime overtaxed the city’s primitive infrastructure and promoted waves of epidemic disease. Originally, Washingtonians obtained drinking water from public wells and natural springs. As they depleted—and polluted—these sources, the government began piping Potomac River water into federal buildings, including the White House. Sewage ran off into the Washington Canal, which emptied into the Potomac and thus polluted this new water supply. In 1853, after a fire consumed the Library of Congress, the federal government initiated a ten-year project to build a serpentine, twelve-mile-long aqueduct to carry fifty million gallons a day from the fresher Potomac water above the Great Falls, for both drinking and fire-fighting. To their credit, Congress continued construction during the war and completed the aqueduct, a masterpiece of hydraulic engineering overseen by Montgomery Cunningham Meigs, in 1863. Until then, pure drinking water was scarce in Washington. As a result, epidemics of smallpox, typhoid fever, and measles plagued the wartime city. Before the war, smallpox was endemic in eastern cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, but rare in Washington. Soldiers from urban areas likely infected the rural recruits and fugitive slaves who arrived by the tens of thousands over the course of the conflict. Before moving to the outskirts of the city, Washington’s smallpox hospital and contraband camp sat near the Capitol, where soldiers and fugitive slaves spread the disease. The human toll was heartrending and included the Lincolns’ 11-year-old son Willie, who succumbed to typhoid fever early in 1862. Lincoln himself nearly died from smallpox in the weeks that followed his Gettysburg Address.

Along with preservation of the Union, the centerpiece of the Lincoln administration’s war effort was of course freedom for America’s four million slaves. Fittingly, the city of Washington helped lead the nation’s movement toward emancipation. In April 1862, Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act, which freed the District of Columbia’s three thousand slaves. Thirteen years earlier, as a U.S. Representative from Illinois, Lincoln had introduced a plan to end slavery in the District of Columbia through voluntary, compensated, and gradual emancipation. The plan failed in the face of southern opposition. With the secession of eleven southern states and the outbreak of the Civil War, the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia became attainable. A group of Republican senators from the Northeast began campaigning immediately for abolitionism, as both a war aim and a strategy for defeating the Confederacy. In December 1861, Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts submitted a bill proposing the immediate and compulsory emancipation of the District of Columbia’s 3,200 slaves through a program of federal compensation. The Compensated Emancipation Act allotted an average of $300 per slave—about one-third of their prewar value—to all slave-owners who were loyal to the Union, for a total payment of $900,000. Under the Compensated Emancipation Act, all slaves in the District of Columbia were free immediately. Slave-owners had ninety days to submit a petition requesting compensation for their slaves. The petitions, which were written by the slave-owners, identified each slave, provided a personal description, including the slave’s age, physical attributes and condition, complexion and occupational skills and presented an estimated value of each slave for purposes of compensation. All told, the slaves emancipated in the nation’s capital represented about one-tenth of 1 percent of all of the slaves held in bondage in the American South during the Civil War. Beyond the positive impact of emancipation on their own lives and those of their family members, the greatest legacy of this first emancipation as it is known was to set an example of how the government could provide for the blanket freedom of an entire group of slaves as an “act of justice,” as Lincoln put it in the Emancipation Proclamation that followed eight months later. [6]

During the war, forty thousand fugitive slaves fled to the nation’s capital, hoping to secure their own freedom and hasten emancipation for those they left behind. Dubbed contrabands in recognition of their official legal status as confiscated contraband of war, they occupied camps run by the government, churches, and private charitable organizations and worked on the city’s military projects. As the number of fugitives grew, the government created a succession of ever larger contraband camps and freedom villages to house them. When the war began, fugitives occupied the Washington jail under the aegis of the Fugitive Slave Law. After Lincoln ordered that fugitives be treated as refugees rather than criminals, they moved to a row of boarding houses across the street from the Capitol (including the room in which Lincoln himself had lodged as a member of Congress). In 1862, when overcrowding produced a smallpox epidemic, the army converted a cavalry barracks on the edge of the city, Camp Barker, into a contraband camp, which accommodated 675 fugitive slaves. In 1863, the army created a more spacious camp, Arlington Freedman’s Village, on Robert E. Lee’s confiscated estate across the Potomac River in Virginia. Freedman’s Village was designed to ease the transition from slavery to freedom by allowing its one thousand residents to feed themselves by farming abandoned land. As a symbol of emancipation and independence located on the former Lee estate, the government kept Arlington Freedman’s Village open long after the war, closing it in 1890 to accommodate suburban growth around Washington.

Thousands of Washington’s fugitive slaves joined the Union army after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation allowed them to enlist beginning in January 1863. Washington had more military-age African American men than eleven of the free states, and just 150 fewer than the entire state of Massachusetts. The city’s African American community mobilized immediately to raise a regiment and in April 1863 organized the First Regiment of Colored Volunteers. In May 1863, when the Union army created the Bureau of Colored Troops, Washington’s infantry regiment was the first to be mustered into federal service as the 1st Regiment United States Colored Troops (USCT). Perhaps because of their prominence as the 1st USCT, the regiment attracted recruits from twenty-two states and five foreign countries. During their two years of service, the 1st Regiment USCT fought in six battles in Virginia, including Wilson’s Wharf, Petersburg, and Fair Oaks, and five engagements in North Carolina, including two at Fort Fisher. They took part in Sherman’s march through North Carolina, which culminated in General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s surrender in April 1865. By the time they were mustered out in October 1865, the 1st Regiment had lost 185 men, including five officers, a 15 percent fatality rate.

During the Civil War, Senator Charles Sumner called the District of Columbia “an example for all the land” that would occupy the vanguard of freedom, equality, and justice as the nation fought the Civil War and rededicated itself to those founding principles. [7] After slavery ended in the District of Columbia in April 1862, Washington’s African Americans insisted on legal equality as another unanticipated but imperative consequence of the war. Their campaign for equality initially focused on equal access to public transportation. As one of the capital’s wartime public improvements, Congress chartered the Washington and Georgetown Railroad, the city’s first streetcar line, in May 1862. The cars were racially segregated. In August 1863, a group of African American ministers challenged the streetcar company’s segregation policy by boarding a whites-only car, from which they were ejected. In the following year, the ejection of African American soldiers in uniform, along with the forcible removal of the famed equal rights advocate Sojourner Truth, brought the highly publicized streetcar campaign to the attention of Republicans in Congress. In July 1864, when Congress granted a charter to a second streetcar line, Sumner insisted on a clause forbidding racial segregation on any streetcar in the District of Columbia. The wartime integration campaign culminated in March 1865, when Congress approved Sumner’s proposal to extend this equal access provision to every railroad line in the nation’s capital. Washington was the first southern city to integrate its public streetcar system, as well as the first to achieve the elimination of its black code, the creation of public schools for African Africans, the empaneling of African Americans as jurors, and—once the war ended—the adoption of manhood suffrage and office holding.

Through all of this public turmoil and triumph, privately the Lincolns shared both everyday joys and unbearable anguish as the divided nation’s first family. Abraham and Mary Lincoln cherished their boys, Willie and Tad, beyond measure and gave them the run of the White House, often to the consternation of the president’s secretaries and other officials. To escape the muggy Potomac weather, the Lincolns retreated to higher ground north of the White House, spending three of their summers at the Soldiers’ Home, a 300-acre retreat for disabled veterans. Overall, Abraham Lincoln spent about one-fourth of his time in the presidency sleeping in the Soldiers’ Home and commuting daily to the White House. Yet this time together proved fleeting, and the family faced a surprising degree of separation. Abraham Lincoln spent a total of 69 days away from Washington, usually by himself, mostly visiting the front but also speaking at Gettysburg and appearing at Sanitary Commission Fairs. Mary Lincoln traveled even more extensively, spending one, two, or three months at a time in Philadelphia and New York, procuring new furnishings for the White House, which she considered one of her most important contributions to raising national morale. The Lincolns’ sons, Willie and Tad, usually traveled with their mother, but they all kept in frequent contact by exchanging telegrams, sometimes daily. The family’s greatest personal tragedy, of course, was the death of their beloved Willie. Abraham Lincoln grieved terribly but had to rebound quickly for the sake of the nation. Mary Lincoln, however, sank into a depression from which she never fully recovered. Willie’s loss united both of them in sacrifice with the rest of the country. Overall, the Civil War took an extraordinary toll on Washington’s permanent and temporary residents, but their struggles and sacrifices helped to win the war, preserve the Union, end slavery, and transform the city into a larger and more modern national capital.

- [1] Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 10 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 6:226.

- [2] John Hay, Lincoln and the Civil War in the Diaries and Letters of John Hay (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1939), 1.

- [3] Basler, Collected Works, 6:341.

- [4] John G. Barnard, A Report on the Defenses of Washington (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1871), 125.

- [5] Basler, Collected Works, 6:226-7.

- [6] The Emancipation Proclamation in Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/alrb/step/01011863/001.html accessed March 11, 2016.

- [7] Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in the Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 1.

If you can read only one book:

Winkle, Kenneth J. Lincoln’s Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, DC. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

Books:

Brownstein, Elizabeth Smith. Lincoln’s Other White House: The Untold Story of the Man and His Presidency. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

Gibbs, C. R. Black, Copper, and Bright: The District of Columbia’s Black Civil War Regiment. Silver Spring, MD: Three-Dimensional Publishing, 2002.

Harrison, Robert. Washington During Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Hay, John. Lincoln and the Civil War in the Diaries and Letters of John Hay. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1939.

Kurtz, Michael J. “Emancipation in the Federal City,” Civil War History, 24 (September 1978): 250-67.

Lee, Richard M. Mr. Lincoln’s City: An Illustrated Guide to the Civil War Sites of Washington. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1981.

Leech, Margaret. Reveille in Washington, 1860-1865. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1941.

Masur, Kate. An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle for Equality in Washington, D.C. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Melder, Keith. City of Magnificent Intentions: A History of Washington, District of Columbia. Washington: Intac, 1997.

Pinsker, Matthew. Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

Civil War Washington is a website that examines the U.S. national capital from multiple perspectives as a case study of social, political, cultural, and medical/scientific transitions provoked or accelerated by the Civil War.

Other Sources:

Lincoln

Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment DVD, 2013.

Lincoln’s Washington at War

Smithsonian Channel DVD, 2013.