Nathan Bedford Forrest

by Michael R. Bradley

It has been said that Bedford Forrest was the most effective cavalry commander produced by the Civil War. It has also been said that Forrest is the most controversial figure produced by the war. Born in 1821, by 1860 Forrest had amassed a fortune of $1.5 million in the business of trading livestock, land and slaves. Commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in 1861 he raised the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry regiment. In his first major engagement at Fort Donnelson in February 1862 Forrest refused to surrender along with the rest of the Confederate garrison and led 4,000 men to safety through Union lines. Forrest fought at Shiloh in April 1862 where he led the Confederate rear guard stopping the Union pursuit and was severely wounded. In July 1862 he was promoted to Brigadier General after he led his cavalry brigade to victory at the First Battle of Murfreesboro. In December 1862 Forrest destroyed Grant’s supply line in Tennessee forcing Grant to call off his Vicksburg Campaign. In September 1863 he led his men at Chickamauga and harassed the Union army as it retreated towards Chattanooga. The most notorious incident in Forrest’s career involved the massacre of USCT troops at Fort Pillow in April 1864. Whether from a deliberate order which was rescinded or through the heat of combat, Forrest’s role in the massacre remains a source of debate today. Forrest’s men fought at the battles of Franklin and Nashville in late 1864. Hearing of Lee’s surrender Forrest surrendered his remaining force at Gainesville Alabama on May 9, 1865 where he gave his famous proclamation to his men. Post war Forrest attempted to rebuild his fortune but failed. Controversy dogged him further when he became the first leader of the Ku-klux Klan, then ordered it dissolved (or some argued ordered it to go underground) in 1869 and then confusingly denied it all in Congressional testimony in 1871. He died in Memphis at the home of his son in 1877. Today Forrest remains controversial. Originally buried at Elmwood Cemetery, in 1904 his and his wife’s remains were reinterred under a statute in a Memphis city park originally named Forrest Park since renamed Health Science Park and now the subject of a movement to have the statute and their remains moved once again.

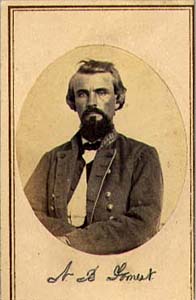

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Photograph Courtesy of: Alabama Department of Archives and History

It has been said that Bedford Forrest was the most effective cavalry commander produced by the Civil War. It has also been said that Forrest is the most controversial figure produced by the war. Both statements have merit. Forrest is considered an outstanding cavalry leader because of his mastery of the technique of deep penetration raids during which his command disrupted Federal logistic networks and because of his victories over superior forces during his defense of a major food producing area in Mississippi in 1864. Controversy swirls around Forrest because of a massacre of United States Colored Troops (USCT) at Fort Pillow in April, 1864, and because of his widely-believed involvement with the Ku Klux Klan following the war. More stories and myths are associated with Forrest than with any other major figure from the Civil War and many of these are uncritically accepted as factual, but the man is more complex than his legend. [1]

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born on July 13, 1821, near the village of Chapel Hill in Bedford County, Tennessee (a redrawing of county boundaries has placed Chapel Hill in Marshall County). He was the oldest son of William and Mary Beck Forrest, and would be one of ten siblings, including a twin sister who died at an early age. William Forrest, the father of this large family, was a blacksmith and small farmer but he died when Bedford (the name he preferred) was 16, so the eldest son became the head of the family. In 1833 the family moved to the vicinity of Hernando, Mississippi, and Bedford went into business with an uncle. When his uncle was killed in a dispute with some neighbors, Forrest inherited the business and soon proved his skill as a businessman. Trading in livestock, land, and slaves he amassed a fortune estimated at 1.5 million dollars by 1860, married, and moved with his wife to Memphis, Tennessee where he was elected as an alderman. From his earliest days Forrest was a person of initiative who took every opportunity to gain an advantage; he always tried to be in control of every situation.

Tennessee voted against secession in February 1861. Forrest was known for his opposition to leaving the Union, but, following the beginning of the war in April when Tennessee again voted on the issue, Forrest supported secession. A war had begun, President Abraham Lincoln had called for volunteers to invade the Confederate States, and sides must be chosen. Forrest enlisted as a private in a company being raised in Memphis but his prominence as a business and local political leader caused Governor Isham Green Harris to send him a commission as a lieutenant colonel with the authority to raise a battalion of cavalry. This unit, which Forrest equipped with his own money, was designated the 3rd Battalion, Tennessee Cavalry. The unit grew over time to regimental size and became the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Although designated a Tennessee organization the unit included men from Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri, as well as soldiers from Tennessee.

Following their organization and training, Forrest's command was sent into western Kentucky as part of the army being assembled by General Albert Sidney Johnston. During the late months of 1861 Forrest led patrols as far north as the Ohio River and frequently used his cavalrymen to ambush boats on the river, including the gunboats the federal forces were beginning to use to patrol waterways. In January 1862 Forrest led his men to Fort Donelson near Dover, Tennessee, to become part of the garrison of that place. On February 6, 1862, U.S. forces commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort Henry, a fortification on the Tennessee River some 12 miles west of Fort Donelson. When Grant moved against Fort Donelson on February 12 and 13 Forrest used his cavalrymen to delay the Union advance. A Confederate counterattack was made on February 15 in an attempt to open an escape route. During this attack, Forrest used his men to probe the Union lines for vulnerable points and then to lead infantry forces to attack these points.

In the course of the day, Forrest broke the Union flank three times, captured one six-gun battery, and took two guns from a second battery. At the end of the day, Forrest found that his overcoat had fifteen bullet holes in it.

Although the attack opened a road by which the garrison could have escaped, their commander, Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow inexplicably ordered his men back into their entrenchments. On the night of February 15-16 a council of war decided to surrender the next morning. When he was informed of the approaching surrender Forrest announced his intention of escaping from the fort and led out more men than he numbered in his regiment. This action established Forrest as an uncompromising fighter in the minds of people, South and North. In his first major action Forrest revealed himself to be an independent thinker who was not bound by rigid obedience to decisions made by officers of higher rank; Forrest thought for himself. This characteristic would make him a forceful leader but would make him a difficult subordinate.

Forrest's stature as a leader in a time of crisis was enhanced by his actions in clearing Nashville of most of the military supplies accumulated there before Union forces arrived to occupy the capital city of Tennessee. Forrest also commanded part of the rearguard as the Confederate army fell back into north Alabama and Mississippi.

The weeks between the fall of Fort Donelson and the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862) were spent by Forrest in resting, recruiting, and training his men. Although the Confederacy had been dealt a severe blow by General Grant the reputation established by Forrest allowed him to recruit more men so that his command was larger in April than it had been in January.

At the Battle of Shiloh, Forrest was ordered to guard the crossing of a minor creek and it soon became obvious to him that no federal troops were in the vicinity. Without orders, he led his men into the main battle area and helped anchor the right flank of the Confederate attack. During the night of April 6-7 his scouts discovered that Major General Don Carlos Buell had arrived on the east bank of the Tennessee River and that reinforcements were streaming across to support Grant. During the fighting on April 7 Forrest helped repel three attempts to turn the Confederate flank and, when the army began its retreat to Corinth as night fell, he was placed in charge of the rearguard.

On April 8 Major General William Tecumseh Sherman led his brigade of infantry in pursuit of the Confederates. Less than three miles from the battlefield Sherman's pursuit was confronted by Forrest and approximately 600 cavalrymen. As the U.S. infantry crossed a boggy stream Forrest led 300 of his men in a slashing mounted charge into the blue ranks, creating such confusion that the pursuit was halted. During this charge Forrest was seriously wounded by a shot fired at point blank range and was forced to take a medical leave of three weeks. The operation to remove the bullet was not performed until almost a month after the wound was inflicted and was performed in a hospital by a relative of Forrest, Dr. J. B. Cowan.

The rearguard action following Shiloh, sometimes called the Battle of Fallen Timbers, gave rise to a persistent story which illustrates the way legends have clustered about Forrest. According to the story, when Forrest was wounded he reached down from his saddle and seized a U.S. soldier by the collar, slung him up behind him, and used him as a shield as he galloped back through the blue ranks. Such a feat of strength is unbelievable, yet the story appears in many biographies of Forrest. The story appeared for the first time in 1902 in a book written by a man who was not present while five accounts, written by Confederate participants in the engagement, do not mention such a thing happening. The lack of evidence has not prevented the story being widely circulated and believed because the story involves Forrest. Such an account would never have gained credence if the protagonist was Major Generals Joseph Wheeler or JEB Stuart or any Union cavalry commander, but Forrest is a legendary figure, so the legend has taken on a life of its own.

When Forrest returned to the army, now concentrated in and around Corinth, Mississippi, he was told that he had been recommended for promotion to brigadier. In mid-June, 1862, he was sent to Chattanooga to organize a brigade of cavalry and to begin preparations for the move General Braxton Bragg wanted to make into Kentucky. Bragg's proposal was that Confederate forces in Chattanooga should slow the advance of General Don Carlos Buell toward that place while Bragg used the network of railroads to shift his army from Corinth to Chattanooga. Then, before the federal forces in western Tennessee were aware of what was happening, Bragg would sweep into Kentucky, cut all supply routes south, and force the Union armies in Tennessee to fall back to the Ohio to meet the new threat.

Since the Confederate forces in Chattanooga were outnumbered by the advancing army under Buell, Forrest made a typically bold decision; he would attack. His target would not be the soldiers advancing on Chattanooga, the target would be their supply line. This raid against an opponent's logistics network would become a trademark of Forrest for the rest of the war.

Awaiting Forrest in Chattanooga was a band of cavalry from several states who had never served together and many of whom were recent recruits who had neither horses or weapons. Forrest had instructions to organize the 8th Texas, 1st Georgia, 2nd Georgia, remnants of the 1st Kentucky, and Colonel Baxter Smith's Tennessee Battalion into a brigade. The order to organize a brigade of cavalry was an innovation in itself since the Union armies did not have any cavalry organization larger than a regiment. Forrest took only a few days to create the rudiments of a brigade structure and then set off across the Cumberland Mountains by a circuitous route toward Murfreesboro.

The garrison of Murfreesboro consisted of the 3rd Minnesota Infantry, five companies of the 9th Michigan Infantry, a detachment of the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and the 1st Kentucky Battery, all under the command of Brigadier General Thomas Turpin Crittenden who arrived at the town on July 12. Also in Murfreesboro were 150 civilians being held in the town jail, six of them under sentence of death to be carried out on July 13. Crittenden found his new command scattered in three widely separated camps, an arrangement which he meant to change, but events prevented his doing so.

On July 13, 1862, just as it became light enough to see, Forrest's column of cavalry came charging into town along the Liberty Pike. Forrest's men immediately broke into smaller groups to attack previously designated targets. Much of the ensuing fighting took place on the grounds of the Oaklands mansion (now open as an historic house) and at the courthouse in the center of town (still in use today). The 150 civilian prisoners were saved from a gruesome fate by Forrest's men. As the Union troops fell back from the jail someone set fire to the building, intending to burn to death all the prisoners. Troopers of the 2nd Georgia broke open the doors of the building before the fire engulfed the structure and released the prisoners. By separating each federal force from the others Forrest was able to capture them in turn, although this took most of the day. Andrew Lytle, in Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company recounts the story that one of Forrest’s staff officers advised him that federal reinforcements were likely to arrive from Nashville less than forty miles away by rail and Forrest is said to have replied, “I didn't come here to do no half-way job of it, I intend to have 'em all.” Lytle provides no documentation for the exchange but whether entirely accurate or not, the quote sums up the fierce determination Forrest brought to any fight.

Before sundown, Forrest “had 'em all” and marched his men, their prisoners, and several tons of military supplies out of town for what proved to be a peaceful trip back to Chattanooga. This raid on his supply line caused General Buell to stop his advance on Chattanooga and send troops to the rear to protect his transportation net. This, in turn, allowed General Bragg time to move his army from Mississippi to Chattanooga and begin his sweep into Kentucky.

In the following weeks, as the Confederate army swept north into Kentucky and the Union forces abandoned most of their gains in Tennessee, Forrest continued to harass Union troop movements and to send information of their movement to army headquarters. General Bragg was not pleased with Forrest as a brigade commander with his army, however, although the performance of Forrest in carrying out the role of screening the advance of the army had been quite good. There is no clear reason as to why Bragg was not pleased with Forrest; perhaps it was because of Forrest's lack of military education (or any other sort of education, for that matter), perhaps the more refined Bragg was put off by the lack of civil graces in the unrefined Forrest. At any rate, Forrest was relieved of his command and sent back to Tennessee to raise new troops.

Forrest, somewhat embittered toward Bragg, returned to Middle Tennessee where his reputation soon had recruits flowing to his encampment. As his new command was organized and trained Forrest led them in daily reconnaissance of the isolated Union garrison at Nashville and engaged in frequent skirmishes with foraging parties sent out to attempt to bring in food for the garrison. In November, following the battle of Perryville in Kentucky, the Confederate army returned to Middle Tennessee and Forrest once again took on the traditional role of screening the flank and front of the army. He was assigned to the right flank, watching roads which led south from Nashville, which Major General William Starke Rosecrans had made his base when he succeeded General Buell in command of the Army of the Cumberland. In carrying out this assignment Forrest was literally making a return to the place of his birth since his area of responsibility included Chapel Hill. This allowed him to continue recruiting.

The brigade which Forrest assembled during the autumn of 1862 included some men who had served under his command earlier. The Confederate War Department had established a policy that a unit should be made up of men from the same state. Under that policy the 3rd Tennessee, Forrest's original command, had been broken up into smaller units to reflect state origins. The Alabama troops from the former 3rd Tennessee had become the nucleus of the 4th Alabama and that regiment was now part of Forrest's brigade. Rounding out the brigade were the 4th Tennessee, 8th Tennessee, and 9th Tennessee. While veterans provided a nucleus for each regiment, the bulk of the men had only entered the armed service during the Autumn and had never been in major combat. The armament carried by the men was weak, many of the men carrying double-barrel shotguns brought from home (effective range about 20 yards) and 400 men of the brigade having flint-lock muskets left over from the War of 1812.

Braxton Bragg's strategic move into Kentucky had been successful in clearing most of Tennessee and Mississippi of U.S. forces but, as winter approached, Bragg knew he could not support his army in Kentucky without a railroad to deliver supplies. Both rail lines leading from Tennessee to Kentucky were still controlled by U.S. forces. The Mobile & Ohio passed through Corinth and that post had successfully defended itself against a Confederate attack. The Louisville & Nashville line was controlled by the Union garrison in Nashville, and the Confederates did not have the manpower to mount an assault on that city. By November, 1862, Bragg's Confederates were concentrated near Murfreesboro, some 35 miles southeast of Nashville and forces under Grant had moved out of Memphis and were advancing through central Mississippi in a drive towards Vicksburg.

The strongest force available to the Confederates in the western area was their cavalry. When President Jefferson Davis came west to visit the Army of Tennessee he met General Joseph Johnston, Department Commander, at Chattanooga. There the two men decided to expand and act on an idea which had originated with Field and Line officers in the Texas Cavalry Brigade serving in Mississippi. Simultaneous raids were ordered by Earl Van Dorn, John Hunt Morgan, and Forrest against U.S. lines of supply.

Major General Earl Van Dorn would lead one attack against Grant's base of supplies at Holly Springs, Mississippi.

Colonel (promoted to Brigadier just before his raid began) John Hunt Morgan would attack the Louisville & Nashville; and Forrest would move into West Tennessee to wreck the Mobile & Ohio which fed supplies to the Holly Springs base. These attacks were to begin in mid-December but once they were in the field no attempt could, or would, be made to coordinate their day-to-day activities.

Forrest was not happy with his orders. He was expected to lead 1,800 poorly armed men into an area defended by 17,000 federal soldiers; to do so he would have to cross the more than half-mile wide Tennessee River both on entering and exiting the area of his attack, and would have to dodge gunboats as he did so. Forrest informed his superior officers that he considered the mission to be suicidal and that the destruction of his command was likely. Then he rode west toward his target. While Forrest was often critical of higher ranking officers he considered incompetent or stupid, this acquiescence to orders shows that he was willing to take great personal and professional risks when the potential results served the greater good of the Confederate cause.

The village of Clifton was chosen as the place to cross the Tennessee River and Forrest sent word ahead to a band of partisan rangers to build two small flat boats at that location to facilitate his crossing. He also sent instructions to an unknown agent behind Union lines to purchase 50,000 percussion caps for shotguns and to meet him at a specified location. Throughout the war Forrest always seemed to have at his fingertips people who could provide him with the latest information and provide needed goods. In short, Forrest understood the need for an intelligence network and somehow created one. One of the great untold stories of the war, and one which probably never will be told because of a lack of sources, is how Forrest created and maintained his intelligence network. The willingness of men and women to risk their lives to provide information to Forrest says much about the magnetic personality of the man.

On December 15 and 16, 1862, Forrest's command crossed the Tennessee River and marched a few miles northwest. There they rested for about 36 hours while waiting for the needed percussion caps to reach them. At daybreak on December 18 Forrest struck the Union garrison at Lexington, Tennessee, capturing most of the men and scattering the remainder toward the main Union base in the area, Jackson, Tennessee. The commander at Jackson, Brigadier General Jeremiah Cutler Sullivan, thought Forrest would attack his position in an attempt to capture the supplies gathered there, so Sullivan ordered all the small garrisons in the area to abandon their posts along the railroad and concentrate in Jackson. Forrest was delighted since he did not want the supplies; he had come to destroy the Mobile & Ohio Railroad which Jackson had now left largely unguarded.

Leaving a detachment of fewer than 200 men to demonstrate against Sullivan, Forrest broke the rest of his command into small parties to capture depots, wreck water tanks, and to burn bridges and trestles along the railroad. For the next week Forrest fought a series of small skirmishes which resulted in the capture of the few small garrisons which remained in the area of operations, largely rearmed his command with weapons taken from captured supplies, and burned over 50 miles of bridges and trestles. The opposition to his attack was so feeble that Forrest allowed his men a holiday on Christmas Day and, on December 26, began his withdrawal towards the Tennessee River.

On the last day of the year, December 31, 1862, Forrest found a brigade of Union infantry commanded by Colonel Cyrus Livingston Dunham blocking his path of retreat at Parkers Cross Roads, Tennessee. This was not unexpected since scouts had informed Forrest of the federal position. Forrest disposed his men for an attack, some mounted and some on foot. This attack was succeeding quite well, with many of Dunham's men surrendering, when another U.S. force under General Jeremiah Sullivan approached from Forrest's rear. Forrest had ordered that road blocked but the officer receiving the order did not understand what was expected of him. When informed of the force in his rear Forrest is said to have ordered “Charge 'em both ways!” This story does not appear in any of the earlier biographies of Forrest but Andrew Lytle recounted it, without attribution, in his Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company and it has become a standard part of the Forrest legend. Whether or not these were his actual words, that is what he did. A small force made such a fierce attack on Sullivan that he stopped his advance while Forrest led the majority of his men off the field and continued towards the river crossing.

The battle at Parkers Cross Roads reveals additional characteristics of Forrest. He remained calm under pressure and, despite the loss of some men and supplies, extricated his command from danger. Also, Forrest did not blame the surprise move into his rear on the officer who was supposed to block the road. On review of the matter Forrest agreed that the order given was vague and confusing. His response was to seek out a former railroad executive, Charles Anderson, to whom Forrest dictated orders and Anderson wrote them in a clear and understandable form.

The success of the three Confederate raids in December 1862 was striking. General Ulysses Grant had to retreat from Mississippi to Memphis, Tennessee, giving up his first attempt to capture Vicksburg. Forrest had so thoroughly destroyed Grant's supply line that the Union forces would make no move for the next six months. While the raids were in progress, General William S. Rosecrans had won a tactical victory at Murfreesboro, Tennessee (the Battle of Stones River) but the success of John Hunt Morgan's raid against the Louisville & Nashville Railroad pinned Rosecrans in place for the next six months. With Grant inactive, the Confederates concentrated their cavalry in Middle Tennessee to support General Bragg who had made his headquarters at Tullahoma.

From January to July, 1863, Forrest was stationed on the left flank of the Army of Tennessee, under the immediate command of General Earl Van Dorn. The cavalry guarded food supplies and fought a series of sharp engagements with Union probes south out of Murfreesboro. In January, Forrest was part of an abortive expedition to place a temporary blockade on the Cumberland River, the only remaining supply line for the Union forces in Middle Tennessee. An attack was made on the Union garrison at Dover, Tennessee, and Forrest fought hard but the attack failed. Following the battle Forrest informed his commanding officer, General Joseph Wheeler, that he would never again fight under Wheeler's command. This confrontation added to Forrest's reputation as a maverick but it also shows his intolerance of poor leadership. Forrest felt the attack against a fortified position should never have been ordered and that lives could have been saved by not fighting at Dover while accomplishing the task of blocking the river elsewhere.

As spring approached Forrest participated in engagements at Spring Hill, Brentwood, and Thompson's Station. His most notable achievement was the pursuit and capture of a U.S. raiding party commanded by Colonel Abel Delos Streight. Forrest used his by now standard tactics of bluff and illusion to convince Streight that Forrest badly outnumbered him when the truth was the opposite; Streight surrendered to inferior numbers. On his return from this success Forrest found himself in charge of all the cavalry on the Confederate left flank, Van Dorn having been killed by a jealous husband during Forrest's absence. Forrest also received promotion to Major General.

In late June, 1863, General William Rosecrans finally had gathered enough supplies and manpower to undertake another forward thrust. The reaction of the Confederate forces was to concentrate in the area around Tullahoma, Tennessee, and to look for an opportunity to defeat Rosecrans. Forrest played a prominent part in this campaign of maneuver and, when Bragg proved unable to hold on to Middle Tennessee, Forrest continued to protect the Army of Tennessee as it fell back to Chattanooga and then continued to retreat into northern Georgia. Finally, in September, Bragg found the opening he had been seeking and moved to sever Rosecrans from his base of supplies at Chattanooga. As this campaign developed the responsibilities given Forrest had increased until he was commanding an entire cavalry corps.

In a short time, Forrest had advanced from leading a regiment to commanding a brigade, then a division, and now a corps. At each stage of his promotions he had to learn the responsibilities and techniques necessary to perform well in his new role. He made mistakes as he learned to handle his new responsibilities but it is notable that he did not make the same mistake twice; Forrest managed a steep learning curve capably.

During the maneuvering around Chattanooga and into North Georgia, as Rosecrans slowly advanced and Bragg gradually fell back, Forrest carried out the traditional role of a cavalry commander, screening the front of his own army and scouting the position of the opponent. Rosecrans advanced too far into Georgia and realized his scattered forces were vulnerable, so he ordered a concentration at Chattanooga. As the Union army fell back toward that town, Forrest led the pursuit and his men fired the first shots of the Battle of Chickamauga at Reed's bridge on September 18, 1863. On September 19 Forrest led his men in a dismounted engagement against the army corps commanded by Union major general George Henry Thomas. During the course of this fighting Confederate Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill, who was new to the Army of Tennessee, asked whose infantry was fighting so well. Hill was astonished to be told the soldiers he was watching were cavalry.

The ability of Forrest's men to fight on foot, which they did on many occasions, might lead to the conclusion that Forrest commanded mounted infantry. Such an assessment would be incorrect. Mounted infantry never fought on horseback, neither did they carry revolvers to allow them to fight mounted. Forrest's men fought on horseback when circumstances demanded and were armed accordingly. It would be more accurate to say that Forrest led men who were cross-trained to fight either as cavalry or as infantry.

Thanks to a blunder on the part of the Union forces, the Confederates won their greatest victory in the western area at Chickamauga and Forrest harried the retreating Union forces as they made their way to Chattanooga. Forrest urgently called on Bragg to attack the Union forces before they could fortify themselves in Chattanooga but Bragg made no offensive move. Disgusted with what he saw as another wasted effort caused by an incompetent commander Forrest sought command elsewhere. According to an account recalled by Dr. J. B. Cowan, Chief Medical Officer of Forrest’s command and a relative., Forrest physically confronted Bragg and threatened to challenge him to a duel or to whip him in a fist fight. Some historians doubt that such a physical confrontation occurred, but at any rate, Forrest was sent with a handful of men to take charge of North Mississippi and West Tennessee. Forrest arrived at his new headquarters not far from Memphis in late November, 1863.

Forrest began to collect small units of Confederate cavalry in the area and to combine and train them into an effective force. His major objective was to protect the food producing area of eastern Mississippi which provided much of the food for the Army of Tennessee, then positioned in north Georgia. In February, 1864, Forrest defeated an expedition into this area led by Major General William Sooy Smith in a fight at Okolona, Mississippi. This defeat so crippled Union forces based in Memphis that Forrest was able to lead his command into West Tennessee for several months.

The western part of Tennessee was now no longer a major site of combat operations and had become a largely unoccupied no-man’s land. Union garrisons were at Memphis, Tennessee; Columbus and Paducah, Kentucky; at a few small posts were along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad to protect the approaches to the major garrisons. This meant Forrest had free range over the area to collect recruits, horses, and food supplies. With his headquarters at Jackson, Tennessee, Forrest moved against smaller Union posts, capturing men and supplies, and mounted a raid against the larger post at Paducah in which he captured considerable amounts of stores. In April, 1864, shortly before leading his enlarged command back to Mississippi, Forrest led an expedition against an isolated Union post at Fort Pillow.

Fort Pillow is not near a town; it had been built in 1861 by the Confederates in an attempt to block the navigation of the Mississippi River. There was no military reason for a Union garrison to be there and General William Sherman, the Theater Commander, had ordered the post abandoned weeks earlier. The Union garrison did provide protection for the surreptitious trade of cotton being sent north. In April, 1864, the post was manned by white Tennessee Unionists and members of the USCT. Forrest demanded the surrender of the garrison and, when this demand was refused, captured the position by direct assault.

The heavy causalities suffered by the garrison led to a Congressional investigation by the U.S. House of Representatives and the report they issued soon caused the results of the battle to be called a massacre. The controversy about how many soldiers were killed in violation of the rules of war and the role of Forrest in the massacre continue to the present day. Most modern historians agree that a massacre did occur. However, the extent of the massacre in violation of the rules of war vs casualties suffered in combat where a position is carried by direct assault, remains unresolved.

Returning to Mississippi, Forrest mounted a campaign to protect the food producing area under his control. This campaign produced a number of victories over superior forces which led to solidifying Forrest's reputation as “The Wizard of the Saddle.” In what Edwin Bearss has called “Forrest’s Masterpiece” at Brice's Cross Roads on June 10, 1864, Forrest used the oppressive heat of a Mississippi summer to his advantage. [2] He attacked the U.S. cavalry which had reached his defensive position while their supporting infantry was several miles to their rear, knowing the sound of the battle would cause the foot soldiers to march at double time to reach the field. Forrest defeated the opposition cavalry and then his men went after the exhausted infantry arriving on the field.

Forrest would win victories and blunt Union drives into the food producing area he was charged to protect for the rest of the summer of 1864, even making a raid into the heart of the Union occupied town of Memphis to disrupt plans for another Union expedition into Mississippi. But, although Forrest won tactical victories, the Union strategic plan was actually served by the events in Mississippi. The great fear of General William Sherman was that Forrest would break into Tennessee and cut his supply line, the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. This was the sole rail line supplying Sherman's forces as they advanced toward Atlanta. Sherman was so aware of the danger of Forrest cutting him off from his base of supplies that he wrote to Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, that Forrest must be killed and “it must be done, if it costs ten thousand lives and breaks the Treasury. [3]

It was not until after the federal capture of Atlanta that Forrest was able to leave Mississippi and make a raid against the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad, and by then it was too late to affect the outcome of the Atlanta Campaign. Forrest made a second raid against the route supplying the U.S. garrison at Nashville, Tennessee, in which he captured U.S. gunboats and briefly manned them with cavalrymen to assist his raid. Although Forrest destroyed the large supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee, he found other duties awaiting him when he returned to safe territory.

At the beginning of November 1864 Forrest took command of the advance guard of the Army of Tennessee as General John Bell Hood led the remains of that force into Tennessee. At the same time, General Sherman was leading his force on the march to the sea. Forrest screened the advance of the Confederate forces but could not prevent the destruction of the Army of Tennessee at the battles of Franklin and Nashville. In the midst of a bitter winter storm Forrest provided an effective rearguard which allowed a fragment of the Confederate force to escape to Mississippi.

In 1865 Forrest led his much weakened command in an attempt to stop General James Harrison Wilson in his sweep through Alabama during which Wilson destroyed Confederate manufacturing centers, including the important arsenal at Selma, Alabama. Selma was Forrest's last battle. He led his men north to Gainesville, Alabama, and surrendered his remaining force on May 9, 1865.

The attitude of Forrest at the end of the war can be seen from his Farewell Address to his command:

Soldiers: By an agreement made between Lieutenant General Taylor, commanding the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, and Major General Dabney, commanding United States forces, the troops of this department have been surrendered. I do not think it proper or necessary at this time to refer to causes which have reduced us to this extremity, nor is it now a matter of material consequences as to how such results were brought about. That we are beaten is a self-evident fact, and any further resistance on our part would be justly regarded as the very height of folly and rashness. The armies of General Lee and Johnson having surrendered, you are the last troops of the Confederate States Army east of the Mississippi river to lay down your arms. The cause for which Chou have so long and manfully struggled, and for which you have braved dangers, endured privations and sufferings and made so many sacrifices is today hopeless. The government which we sought to establish and perpetuate is at an end. Reason dictates and humanity demands that no moe blood be shed. Fully realizing and feeling that such is the case, it is your duty and mine to lay down our arms, submit to the “powers that be” and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land. The terms upon which you were surrendered are favorable, and should be satisfactory and acceptable to all. They manifest a spirit of magnanimity and liberality on the part of the Federal authorities which should be met on our part by a faithful compliance with all the stipulations and conditions therein expressed. As your commander, I sincerely hope that every officer and soldier of my command will cheerfully obey the orders given, and carry out in good faith all the terms of the cartel.

Those who neglect the terms and refuse to be paroled may assuredly expect when arrested to be sent North and imprisoned. Let those who are absent from their commands, from whatever cause, report at once to this place, or to Jackson, Mississippi, or, if too remote from either, to the nearest United States post or garrison, for parole. Civil war, such as you have just passed through, naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings, and so far as it is in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings towards those with whom we have so long contested and heretofore so widely but honestly differed, neighborhood feud, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out, and when you return home a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure you the respect even of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to government, society, or to individuals meet them like men. The attempt made to establish a separate and independent confederation has failed, but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully and to the end will in some measure repay for the hardships you have undergone. In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without in any way referring to the merits of the cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination, as exhibited on many hard-fought fields, has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command, whose zeal, fidelity, and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms. I have never on the field of battle sent you where I was unwilling to go myself, nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the government to which you have surrendered can afford to be and will be magnanimous. [4]

Forrest returned to his home in Memphis broken financially and physically. Despite efforts to recoup his personal finances Forrest was a poor man the rest of his life. His lands in Mississippi were lost to unpaid mortgages or because of unpaid taxes. He died at the home of his son, Willie on October 29, 1877.

The post-war years of Forrest's life have produced an enduring controversy concerning his widely-believed connection to the Ku Klux Klan. Although it is often stated that Forrest founded the Klan this is false. The Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in early 1866 by six young men whose names are known. Forrest was never in Pulaski following the war, had no connection to Pulaski, nor did he ever correspond with the founders of the Klan. It is also commonly stated that Forrest was the head of the Klan. On June 27, 1871, Forrest testified before a committee of the U.S. Congress which was investigating Klan activities. While his responses to questions were sometimes rambling and he often could not remember details about which he was interrogated, the Committee did not charge Forrest with Klan connections or activity and it did praise him for having used his influence against the Klan. While it is often stated that Forrest was involved with the Klan, the actual role he played is not clear and remains a matter of debate among historians. Generally ignored are the numerous documented incidents on which Forrest advocated economic and political opportunities for all citizens of his state since he viewed this as the best path to regain economic prosperity and political stability. In August 1868 Forrest participated in a meeting in Memphis to protest the lynching of four African Americans in the town of Trenton, Tennessee. While this expression of support for the rights of the formerly enslaved was met with scorn in many Northern papers some of the Radical press defended Forrest. Another public expression of this attitude was made on July 5, 1875, when Forrest, by invitation, made a speech to the Independent Association of Pole Bearers, an African American social and political organization. In his address Forrest said “I shall do all in my power to elevate every man, to oppress none... I want to elevate you to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going. . . You have the right to elect whomever you please, vote for the man you think best. . . When I can serve you, I will do it. We have one flag, one country; let us stand together. When you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. . . I am with you in heart and in hand. [5]

Forrest was not a 21st Century man who believed in racial equality; he remained a man of his time, sharing the almost-universal view of white Europeans and Americans in the 19th Century that Anglo-Saxons were superior to other peoples, but neither was Forrest a reactionary racist who sought a return to slavery. Forrest worked to accept the end of slavery and the social changes resulting from the war as indicated by his words to his men in his 1865 farewell address. A recent biographer of Forrest says “The reality is that over the length of his lifetime Nathan Bedford Forrest's racial attitudes probably developed more, and more in the direction of liberal enlightenment, than those of most other Americans in the nation's history.” [6]

Nathan Bedford Forrest

| Born | July 13, 1821 near Chapel Hill in Bedford County, Tennessee |

| Died | October 29, 1877 Memphis, Tennessee |

| Buried | Originally buried at Elmwood Cemetery. In 1904 moved to a Memphis city park originally named Forrest Park, since renamed Health Sciences Park |

| Father | William Forrest |

| Mother | Mary Beck |

| Career Milestones | Trading in livestock, land and slaves in a business near Hernando Mississippi Forrest amassed a fortune estimated to be $1.5million by 1860 | October 1861 commissioned Lieutenant Colonel and given command of the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry | February 1862 led his men and others out of Fort Donelson rather than surrender to Grant along with the rest of the garrison | April 1862 fought at Shiloh, commanded the Confederate rear guard fighting at the Battle of Fallen Timbers where he was severely wounded | July 1862 led a cavalry brigade to victory at the First Battle of Murfreesboro and was promoted to brigadier general | December 1862 destroyed Grant’s supply line from Jackson Tennessee to the Kentucky line forcing Grant to abandon his attack on Vicksburg | April 1863 defeated Colonel Abel Streight near Cedar Bluff Alabama ending his raid into Alabama and Georgia aimed at cutting off Braxton Bragg’s supply line | September 1863 served at Chickamauga and pursued the retreating union army | April 1864 attacked and captured Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River, the scene of the still furiously debated massacre of USCT troops | June 1864 defeated Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads | August – October 1864 conducted various raids destroying Union supplies in Tennessee | November 1864 fought at the Battle of Franklin | December 1864 fought at Third Murfreesboro and the Battle of Nashville where Forrest commanded the rear guard and was promoted to Lieutenant General | May 1865 surrendered and gave his farewell address to his troops | Post war Forrest tried unsuccessfully to rebuild his fortune and died at the home of his son in Memphis in 1877. |

- [1] The event at Fort Pillow, April 12, 1864, became a matter of controversy almost immediately. Newspaper reports of the fighting emphasized the heavy causalities among the garrison, especially among the USCT while the Confederates pointed out that the fort was captured by direct frontal assault and that the garrison never surrendered as a group. A Congressional investigating committee published a report which was calculated to rouse support for the war effort at a time when the fortunes of the Union were low. This matter is discussed in Brian Steel Wills, The River Was Dyed With Blood: Nathan Bedford Forrest and Fort Pillow (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 148-61. It is generally assumed that Forrest was the head, or Grand Wizard, of the Ku Klux Klan. An anecdote included by Andrew Lytle in Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company (New York: Minton, Balch and Company, 1931) relates that Forrest was selected as Grand Wizard in a meeting held at the Maxwell House Hotel in Nashville in 1867. However, Lytle provides no documentation for this anecdote, does not give the names of any of those said to have been present, does not give a date for the event. The identification of Forrest as the head of the Klan has now been repeated in so many secondary sources that it has become accepted as historical fact, but the truth is there is no primary source material to show Forrest was the Grand Wizard of the Klan. There are many anecdotes and some circumstantial evidence that Forrest was involved with the Klan but primary source documentation is absent. In the most recent book on the history of the Klan, Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), Elaine Frantz Parsons writes on page 50 “There is also no compelling contemporary evidence to establish that Forrest ever exercised any leadership functions.” The chapter entitled “The Roots of the Ku Klux Klan” is quite compelling in demonstrating the lack of evidence for the idea that Forrest was the first Grand Wizard of the Klan. Because similar local vigilante groups and organizations spread throughout the South in the reconstruction period it is difficult to determine what the Klan was responsible for and how effective it was. That it existed and operated during Reconstruction from 1866 to about 1877 is clear. That it was an effective, monolithic, South-wide organization with bureaucratic leadership is less certain. In common with historians such as Allen Trelease in White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979) and Ben H. Severance in Tennessee’s Radical Army: The State Guard and its Role in Reconstruction, 1867-1869 (Knoxville, University of Tennessee Press, 2005), Parsons discusses this issue and the various vigilante organizations that operated at that time.

- [2] Edwin C. Bearss, Forrest t Brice’s Cross Roads and in North Mississippi in 1864 (Dayton, OH: Morningside Bookshop, 1987), 1.

- [3] United States War Department, War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, volume 36, part 2, p. 121,141.

- [4] John Allan Wyeth, That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1899), 613-4.

- [5] Jack Hurst, Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1993), 366-7.

- [6] Ibid., 385.

If you can read only one book:

Wyeth, John Allan. That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1899.

Books:

Bradley, Michael R. Nathan Bedford Forrest's Escort and Staff, Gretna, LA: Pelican Press, 2006.

Cimprich, John and Robert C. Mainfort. “Fort Pillow Revisited: New Evidence About an Old Controversy,” in Civil War History 28, no., 4 (December 1982): 293-306.

———. “Dr. Fitch's Report on the Fort Pillow Massacre,” in Tennessee Historical Quarterly 44, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 27-39.

———. “The Fort Pillow Massacre: A Statistical Note,” in Journal of American History, 76, no. 3 (December 1989): 830-7.

Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 1993.

Jordan, Thomas and J.P. Pryor. The Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. N. B. Forrest and of Forrest’s Cavalry. New Orleans, LA/Memphis, TN: Beleock & Company, 1868.

Maness, Lonnie E. An Untutored Genius: The Military Career of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, Oxford, MI: The Guild Bindery Press, 1990.

Parsons, Elaine Frantz. Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan during Reconstruction (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Wills, Brian Steel. A Battle From the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992.

Wills, Brian Steel. The River Was Dyed With Blood: Nathan Bedford Forrest & Fort Pillow. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.