The Civil War in Film

by David B. Sachsman

The Civil War is a central focus of American history and American historical scholarship, and yet our image of the time is of Scarlett O’Hara as much as it is of Abraham Lincoln, and the pictures in our heads of Abraham Lincoln come from movies more than history books. The essence of great fiction may be its essential truth. The Red Badge of Courage is a meaningful, truthful picture of the Civil War. But are we equally well served by best-selling fictions, from Gone With the Wind to Cold Mountain? And can we put any trust at all in the stories and pictures of the Civil War provided by movies and television? Sometimes the answer is yes—as in the scene in Gone With the Wind where wounded Confederate soldiers lie on the ground at the Atlanta railroad depot waiting for medical attention. Also meaningful is the depiction in Glory (1989) of the African-American troops of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at the Battle of Fort Wagner, in which the sounds and scenes of war are harrowingly reenacted. Sometimes the answer is no. The final scenes of The Birth of a Nation depict the righteous Klan defeating the cowardly Union troops, who are African American. The Klan is seen riding to regain control of the town and to save Elsie (played by Lillian Gish) from being forced to marry Silas Lynch, and also to save the Camerons, who are being attacked by Lynch’s militia. Victorious, the clansmen parade in the streets as people wave and cheer from their windows. The list of Civil War movies, television miniseries, and documentaries that have been remembered through the years and which form our collective memory about the Civil War period include: The Birth of a Nation (1915), The General (1927), Gone With the Wind (1939), They Died With Their Boots On (1941), The Red Badge of Courage (1951), Friendly Persuasion (1956), The Horse Soldiers (1959), How the West Was Won (1962), The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Roots (1977), The Blue and the Gray (1982), North and South (1985, 1986, 1994), Glory (1989), The Civil War (1990), Gettysburg (1993), Ride with the Devil (1999), Gangs of New York (2002), Cold Mountain (2003), and Lincoln (2012). All in all, these movies and many others, taken together, for the last one hundred years, have provided each and every generation of Americans with the pictures in our heads—our collective memory—of the Civil War, and these views have affected the American experience from then until now.

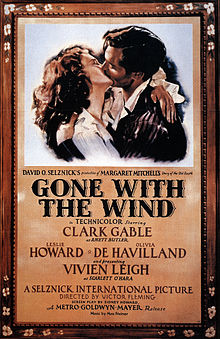

1939 Film Poster for Gone With The Wind

Credit: Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Poster_-_Gone_With_the_Wind_01.jpg

“The Civil War is a central focus of American history and American historical scholarship, and yet our image of the time is of Scarlett O’Hara as much as it is of Abraham Lincoln, and the pictures in our heads of Abraham Lincoln come from movies more than history books.”[1]

“We have seen Lincoln many times on television and in the movies. He is wise, humble, tall but stooped over, frightfully thin, soft-spoken, even hesitant, and when he speaks he speaks slowly and very simply. He is old. He wears a beard to hide his common features, and he is always dressed in black, which makes sense because he spends night and day grieving for the dead on both sides of a horrible, tragic conflict that threatens to destroy the nation and disgrace the very concept of democracy.”[2]

He is a clean-shaven, straight-shouldered Henry Fonda in John Ford’s 1939 Young Mr. Lincoln. He is a somber Raymond Massey in Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940). And he is an aged Daniel Day-Lewis in Steven Spielberg’s movie Lincoln (2012).

The pictures in our heads of the Civil War have come from movies for more than one hundred years. D. W. Griffith’s controversial silent-film spectacular The Birth of a Nation (1915) is based on Thomas Dixon Jr.’s racist 1905 novel, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. It claims to reflect history, and the historical record used is supposedly Woodrow Wilson’s History of the American People. [3] The film quotes Wilson:

Adventurers swarmed out of the North, as much the enemies of the one race as of the other, to cozen, beguile, and use the negroes. . . . In the villages the negroes were the office holders, men who knew none of the uses of authority, except its insolences.

The policy of the congressional leaders wrought...a veritable overthrow of civilization in the South...in their determination to “put the white South under the heel of the black South.”

The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation...until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.

In the film, Ben (played by Henry Withall) sees white children pretending to be ghosts to scare off the black children. This inspires Ben as he decides to fight back against the black legislature by forming the Ku Klux Klan.

David O. Selznick’s Gone With the Wind (1939) begins with a prologue characterizing the theme of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 bestseller: [4]

There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South…

Here in this pretty world Gallantry took its last bow…

Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave…

Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered.

A Civilization gone with the wind…

Mitchell’s romantic novel about the Lost Cause of the Confederacy had a similar vision of the South as did Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman, but it was far less controversial, winning the 1937 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

In the motion-picture version of Gone With the Wind, Mammy (played by Academy Award-winning Hattie McDaniel) is seen chastising Scarlett, showing a romanticized vision of the master–slave relationship that is racist, but far less sinister than the depiction of African Americans in The Birth of a Nation. Our concepts of slavery come from such fictional depictions, just as they did in the 1850s in the North, where the dominant image of slavery came from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.[5]

Civil War Films: Myth or Truth?

“The essence of great fiction may be its essential truth. Our best pictures of England in the nineteenth century are provided by Charles Dickens, just as our understanding of nineteenth century whaling is based on Moby Dick. We believe almost everything we read in War and Peace, especially its images of the essential feeling of war. Likewise, The Red Badge of Courage is a meaningful, truthful picture of the Civil War. But are we equally well served by best-selling fictions. . .from Gone With the Wind to Cold Mountain? And can we put any trust at all in the stories and pictures of the Civil War provided by movies and television?”[6]

The television miniseries Roots (1977) is much more realistic than the opening scenes of Gone With the Wind. Roots shows Kunta Kinte (played by LaVar Burton) first being taken from Africa, whipped, and put into cages with the other soon-to-be slaves. These scenes also show some of the horrible conditions on the slave ship.

The 1951 movie The Red Badge of Courage, like Stephen Crane’s 1895 novel, is a meaningful, truthful picture of the Civil War. The movie, like the novel, is about cowardice, desertion, and redemption. The Youth (played by celebrated war veteran Audie Murphy) is first overcome by his doubts, but finally faces his fears.

Are we usually well served by Civil War films? Sometimes the answer is yes—as in the scene in Gone With the Wind where wounded Confederate soldiers lie on the ground at the Atlanta railroad depot waiting for medical attention. Also meaningful is the depiction in Glory (1989) of the African-American troops of the 54th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at the Battle of Fort Wagner, in which the sounds and scenes of war are harrowingly reenacted.

Sometimes the answer is no. The final scenes of The Birth of a Nation depict the righteous Klan defeating the cowardly Union troops, who are African American. The Klan is seen riding to regain control of the town and to save Elsie (played by Lillian Gish) from being forced to marry Silas Lynch, and also to save the Camerons, who are being attacked by Lynch’s militia. Victorious, the clansmen parade in the streets as people wave and cheer from their windows.

Donald Bogle lists our stereotypes of African Americans as “Toms, Coons, Mulattos, Mammies, and Bucks.”[7] Gone With the Wind features all these stereotypes, including that of Prissy, who is reminiscent of Topsy from Uncle Tom’s Cabin and even more derivative of the 1930s movie character Stepin Fetchit and the radio characters the Gold Dust Twins. These characters combined ignorance with laziness in the most racist of caricatures.

Are Films a Product of Their Times?

Sometimes movie images have more to do with the period in which they were filmed than with the period they are depicting. The characters portrayed in Cold Mountain (2003) appear very different from those in earlier films. While the characters in Gone With the Wind and The Red Badge of Courage were clean-shaven with neat 1930s or 1950s haircuts, the characters in Cold Mountain look a lot more like scruffy actors from 2003. And while the strongest language in Gone With the Wind is “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” the language in Cold Mountain is much more explicit.

Even more importantly, Civil War films reflect the myths and prejudices present at the time in which they were produced. Thus, The Birth of a Nation reflects the prejudices existing in the South when Dixon first wrote The Clansman in 1905, and the prejudices that still existed in much of white America when the motion picture was shown in 1915. And Gone With the Wind reflects the degree of racism accepted as the norm in the 1930s. Roots, on the other hand, tells the story of slavery through the eyes of the slaves themselves, reflecting changes in American feelings brought on by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. And Glory’s presentation of powerful images of African-American soldiers consists of a bold retelling of the Civil War story that provided new information to its audiences, who by 1989, were judged willing to accept it.

Civil War Films to Remember

Our culture as a people is based on our collective memory. Should we be disturbed that our memory often is based on fiction and film rather than history? Through the years there have been hundreds of feature films made about the American Civil War, and there have been hundreds more, mainly Westerns, in which the Civil War plays some part. Counting television, the numbers may be in the thousands. Most of these films and television depictions have been standard commercial fare that may have made some impression when first shown, but have not lasted in our memory.

The movies produced by the studio system paid little attention to the historical record. The major studios of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, usually ignored the facts of history when they got in the way of telling a good story. For example, Warner Brothers’ They Died with Their Boots On (1941), a story about the life of George Armstrong Custer, contained so many deviations from the existing historical record that there is no doubt that the writers knowingly twisted the truth. Since the 1970s, however, some producers and directors have seriously consulted the scholarship of their time in an effort to tell their stories in a more realistic fashion. Thus, Glory drew on years of scholarship concerning race and slavery, and Spielberg consulted modern historians for Lincoln.

The list of Civil War movies, television miniseries, and documentaries that have been remembered through the years and which form our collective memory about the Civil War have both reflected our changing ideas and influenced our belief:

The Birth of a Nation (1915), directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish, was the most controversial and one of the most influential movies ever made about the Civil War. Some even credit the film for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. This is not only one of the most important movies ever made, it is also one of the most biased and racist.

The General (1927), directed by and starring Buster Keaton, is one of the finest silent-film comedies ever made. It tells the story of the great locomotive chase, in which a handful of Union volunteers took over a Confederate train and headed it northward toward Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Gone With the Wind (1939), produced by David O. Selznick and starring Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh, is one of the best-known movies of all time. More than seventy years after its first release, it continues to appear on television on a regular basis. It depicts as truth every Civil War myth and stereotype imaginable, and it accurately reflects the racism of its time.

They Died With Their Boots On (1941), directed by Raoul Walsh, stars Errol Flynn as George Armstrong Custer. It is one of a series of Errol Flynn adventure movies loosely based on famous characters. In this case, while the film had little to do with the historical record, it played a major role in continuing the prominence of Custer as a mythic figure.

The Red Badge of Courage (1951), directed by John Huston and starring Audie Murphy, is one of the most serious and realistic films about the Civil War. It is rarely seen, perhaps because it was filmed in black and white.

Friendly Persuasion (1956), directed by William Wyler, stars Gary Cooper as the head of a pacifist Quaker family caught in the midst of the Civil War. Adapted from the 1945 novel by Jessamyn West, it is a serious motion picture that is also a classic 1950s Western. [8]

The Horse Soldiers (1959), directed by John Ford and starring John Wayne and William Holden, is a 1950s John Wayne Western with a Civil War theme.

How the West Was Won (1962), directed by Henry Hathaway, John Ford, and George Marshall, stars Henry Fonda, Gregory Peck, Debbie Reynolds, Jimmy Stewart, and a cast of thousands in what was essentially five Western movies tied together by a central theme. Shot in a three-projector Cinerama process, it was originally shown on a giant curved screen. The Civil War segment, directed by Ford, includes John Wayne playing General Sherman in a cameo role.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), directed by Sergio Leone, is a so-called Italian “Spaghetti Western” starring Clint Eastwood in a dark, gritty, violent role very different from a 1950s John Wayne Western. While it includes lots of Confederate and Union soldiers, any connection to the history of the Civil War is strictly coincidental.

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, is a 1970s “Modern Western” in which former Confederate guerrilla fighter Eastwood transforms from anti-hero to mythic hero in the course of the film. The portrayal and the action are grittier and more realistic than that of a stylized 1960s Spaghetti Western or a 1950s shorthaired, clean-shaven John Wayne Western.

Roots (1977) is the story of American slavery and the African-American experience presented in the format of a soap-opera-like television miniseries. Though full of stereotypes, many of the stereotypes of African Americans are positive, as the series presents generation after generation of heroic figures. Based on Alex Haley’s best-selling 1976 novel, Roots was enormously successful in its day in providing a very different and much more positive view of African Americans—and a more realistic, violent view of slavery—than had been shown in previous films and television series. [9]

The Blue and the Gray (1982) and North and South (1985, 1986, 1994), are television miniseries that are pure soap operas. They were popular in the 1980s and therefore had some effect in terms of the pictures in the heads of viewers at that time.

Glory (1989), directed by Edward Zwick and starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington, tells the then-little-known story of the African-American 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and its white colonel, Robert Gould Shaw. An excellent, realistic war movie, Glory attempts to be historically accurate, an unusual feature for Civil War movies up to that time.

The Civil War (1990) is Ken Burns’ ten-hour television documentary miniseries. Using photographs of the time, interviews with historians, and a script based on the historical record, Burns’ The Civil War is the finest and most influential documentary of the Civil War ever made. With some forty million PBS viewers in 1990 and tens of millions more through the years, The Civil War may have been viewed by more people than have read history books about the Civil War from then to today.

Gettysburg (1993), directed by Ronald F. Maxwell, is based on Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Killer Angels (1974). True to the book, though somewhat dull, the movie was distributed by Ted Turner’s New Line Cinema. [10]

Ride with the Devil (1999), directed by Ang Lee, which tells the story of a small group of Confederate guerrillas, may be the most internally authentic and externally realistic motion picture about the Civil War since Red Badge of Courage.

Gangs of New York (2002), starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is Martin Scorsese’s picture of New York City street life leading up to and during the Draft Riots of 1863. As always, Scorsese explores the thoughts and actions of real people in real circumstances. The pictures he provides of New York in the Civil War era are the best available anywhere.

Cold Mountain (2003), directed by Anthony Minghella and starring Jude Law and Nicole Kidman, is based on Charles Frazier’s bestselling 1997 novel about a Confederate deserter’s attempt to return home to his wife. Like the book, it is historically and internally accurate, the story of real people in dire circumstances. [11]

Lincoln (2012) is Steven Spielberg’s answer to Gone With the Wind, Roots, and Glory, his attempt at an epic masterpiece that sets the record straight about Lincoln (played by Daniel Day-Lewis), the end of the Civil War, and the politics surrounding the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery in the United States. Along with The Civil War documentary and Cold Mountain, it best represents today’s vision of the Civil War era.

All in all, these movies and many others, taken together, for the last one hundred years, have provided each and every generation of Americans with the pictures in our heads—our collective memory—of the Civil War, and these views have affected the American experience from then until now.

- [1] David B. Sachsman, preface to Memory and Myth: The Civil War in Fiction and Film from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Cold Mountain, by David B. Sachsman, S. Kittrell Rushing, and Roy Morris Jr., eds. (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2007), ix.

- [2] David B. Sachsman, foreword to Lincoln Mediated: The President and the Press through Nineteenth-Century Media by Gregory A. Borchard and David W. Bulla (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2015), xi.

- [3] Thomas Dixon Jr., The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company 1905); Woodrow Wilson, A History of the American People, 10 vols. (New York: Harber & Brothers, 1918).

- [4] Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind (New York: McMillan, 1936).

- [5] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852).

- [6] Sachsman, Memory and Myth, preface, ix; Herman Melville, Moby Dick; Or, The Whale (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1851); Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, 6 vols. (New York: William S. Gottsberger, 1886); Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (New York: D. Appleton, 1885).

- [7] Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 1994).

- [8] Jessamyn West, The Friendly Persuasion (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1945).

- [9] Alex Haley, Roots (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976).

- [10] Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels (New York: David McKay, 1974).

- [11] Charles Frazier, Cold Mountain (New York: Atlantic Monthly, 1997).

If you can read only one book:

Sachsman, David B., S. Kittrell Rushing, and Roy Morris Jr., eds. Memory and Myth: The Civil War in Fiction and Film from Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Cold Mountain. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2007.

Books:

Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob. Telling the Truth About History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1995.

Barrett, Jenny. Shooting the Civil War: Cinema, History and American National Identity. New York: I. B. Tauris, 2009.

Borchard, Gregory A. and David W. Bulla. Lincoln Mediated: The President and the Press through Nineteenth-Century Media. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2015.

Carnes, Mark C. Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies. New York: Henry Holt, 1995.

Chadwick, Bruce. The Reel Civil War: Mythmaking in American Film. New York: Vintage Books, 2009.

Cullen, Jim. The Civil War in Popular Culture: A Reusable Past. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Eberwein, Robert. The War Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Gallagher, Gary W. Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Kinnard, Roy. The Blue and the Gray on the Silver Screen: More Than 80 Years of Civil War Movies. New York: Citadel Press, 1996.

Kreiser Jr., Lawrence A. and Randal Allred, eds. The Civil War in Popular Culture: Memory and Meaning. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Rollins, Peter C., ed. The Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American Past. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Rollins, Peter C. and John E. O’Connor, eds. Why We Fought: America’s Wars in Film and History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

Sobchack, Vivian. The Persistence of History: Cinema, Television and the Modern Event. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Wetta, Frank J. and Martin A. Novelli. The Long Reconstruction: The Post-Civil War South in History, Film, and Memory. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Wills, Brian Steel. Gone with the Glory: The Civil War in Cinema. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

List of Films and Television Shows About the American Civil War on Wikipedia. The Wikipedia page includes links with details about each film.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.