Civil War Music

by Stephen Cornelius

The Civil War affected American musical life at every level. Music affected the war as well. Virtuosos tuned their concert repertoire to fit public sentiment. At home, parlor room music-making was infused with the conflicting emotions of fear and pride, loss and relief. On the fronts, music supported marching soldiers as they sang away fear and exhaustion. Military bands were active throughout the war. Military field music consisted of fifers buglers and drummers who were responsible for transmitting orders as well as playing to encourage or inspire soldiers. Military band music consisted of full-scale brass and percussion ensembles which gave concerts in camp and at various functions but also played during battle to inspire the men. Sometimes, bands simply entertained. Confederate soldiers gathered on a bridge on the Rappahannock River to listen to a Union band before the Battle of Fredericksburg. Colonel James C. Nisbet of the 66th Georgia wrote in his memoirs of a Confederate cornet player along the Kennesaw Mountain line who was much appreciated by the Yankees. Classical music entertainers continued to offer concerts and operas with many musical events linked to the war. Choral societies and outdoor band music continued to thrive, also linking their offering to the war. In terms of commerce music publishing thrived during the war in both North and South. Piano scores were published in great quantity and which not much of the music was memorable, the cover art was often remarkable. In terms of songs “Dixie” “The Bonnie Blue Flag” “Maryland! My Maryland” are among the most famous from the south and “Battle Cry of Freedom” from the North. Anti-war songs like “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground”, “Weeping, Sad and Lonely” and “When This Cruel War is Over” were popular. In the war’s middle years themes of death, often without glory permeated newly composed songs, though most of those are not memorable. Near the war’s end songs reflected optimism and “Marching Through Georgia” is one of the more memorable of these. Songs from the British Isles that pre-dated the war were also popular including “Home Sweet Home” and “Annie Laurie”. “The men who wore the blue, and the butternut Rebs who opposed them, more than American fighters of any period, deserve to be called singing soldiers,” observed historian Bell Irvin Wiley. Aware that soldiers would remember melodies but might forget words, publishers printed dozens of songsters, books of lyrics alone. And as for African American music, the Civil War emancipated it. Through escaped slaves reaching the North or through northern soldiers operating in the South, white northerners were exposed to African-American music, especially the spirituals like “Go Down Moses”. African-American musical and dance styles had been parodied by blackface minstrels since the 1830s, but it was not until the Civil War that most Northern whites began to have direct contact with, and take serious notice of, the real music of African Americans. Music flowed freely across political boundaries and army lines. Northerners and Southerners sang the same songs, Confederate and Union armies sometimes marched to the same melodies. In the evenings, songs of home and faith floated across military encampments. By day, the stern commands of drums and bugles pierced battlefields. Away from the front, bands entertained in city streets and parks, orchestras and choirs filled concert halls, and sentimental songs enlivened parlors. Music’s resonance gave voice to an era. Always, music bound people together, helped them move forward, and helped them to remember.

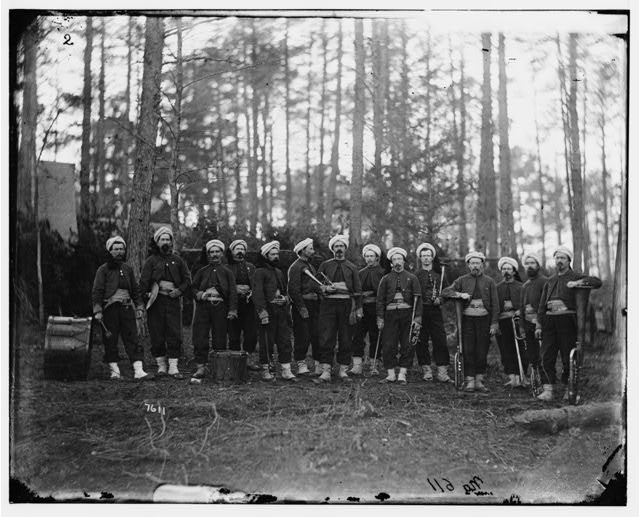

Band of the 114th Pennsylvania Infantry (Zouaves) at Brandy Station Va., April 1864. Photographed by Timothy H. O’Sullivan.

Photograph Courtesy of: The Library of Congress Call No. LC-B817-7611 (P&P) Lot 4190-D

“So strong you thump, O terrible drums—so loud you bugles blow.”

“Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman

The Civil War affected American musical life at every level. Music affected the war as well. Raw would-be instrumentalists flocked to enlistment centers. Virtuosos tuned their concert repertoire to fit public sentiment. At home, parlor room music-making was infused with the conflicting emotions of fear and pride, loss and relief. On the fronts, music supported marching soldiers as they sang away fear and exhaustion. Some music steeled men for combat; other music stirred longings for peace and hearth. A few soldiers wrote that music affected the outcome of the war itself.

Music was ubiquitous, until it was not. Then, silence became the most dramatic sound of all. Wrote Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain at Appomattox, “On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!”[1]

What did music mean to the soldiers? There are many stories, but perhaps the most iconic occurred years after war’s end. The story bears repeating, even in a brief essay such as this.

The year is 1888. You are a veteran and have returned to Gettysburg for the battle’s 25th anniversary Grand Reunion. Among the thousands of former combatants are Confederate generals James Longstreet and John Brown Gordon, and Union generals Chamberlain, Daniel Adams Butterfield, Daniel Edgar Sickles, and Henry Warner Slocum. A Union bugler quietly walks up Little Round Top, puts instrument to lips, and blows a call associated with Butterfield’s command. Heard across the battlefield, the past floods into the present. Veterans, strewn all about, come running in answer to the call, many with tears in their eyes.[2]

Such is the power of music.

This essay divides into four sections: military music, concert music, music-related commerce, and African-American music. The categories overlap, of course, but they provide logical categories by which to get a well-rounded overview of the period’s musical life.

Military Music

Military bands were active at the war’s beginning and end, and most everywhere in between. The Union’s 1st Regiment of Artillery Band was stationed at Fort Sumter for the war’s first confrontation. There, band members helped in the fort’s defense. Later, they performed as the regiment vacated the fort. Just over four years later, bands would support nearly 150,000 soldiers as they marched in the Grand Review of May 23-24, 1865 in Washington.

How many musicians were in the armies? Because of poor record keeping, we don’t know. Union General Order No. 48 of July 31, 1861, allowed two principal musicians, up to twenty field musicians, and up to twenty-four band musicians per regular army infantry or artillery regiment. These numbers were rarely adhered to, however. Some aggregations were much larger; others were smaller, or perhaps none at all. Estimates of Union musicians at the end of 1861 range from 8,000 to 28,000.[3] Estimates for the entire war reach as high as 53,600 musicians in service.[4] While enlistments flowed, then ebbed, there was always plenty of music in the armies, including as many as one hundred brigade bands. Numerous regiments funded, their own bands. Over the course of the war, Union armies purchased some 32,000 drums, 21,000 bugles, and nearly 15,000 trumpets.[5]

Army music divides into two categories: field music (fifers, buglers, and drummers) and band music (full-scale concert ensembles made up of brass and percussion—with woodwinds only rarely). Field musicians sounded calls to initiate basic camp duties and during military operations. Bands concertized.

Field Music

Field musicians—fifers, buglers, and drummers—were at the nerve center of the military. Their duty was to transmit the various orders essential for the army’s day-to-day functioning, whether in camp or on the battlefield. Field music was organized into three categories: the day’s regulatory calls (from “Reveille” to “Taps”), tactical signals (battlefield instructions), and various other duties neither regulatory nor tactical, such as dress parades, funerals, punishments, or entertainment. Some musical sequences were expansive. Others were precise, “just so many words of command.”[6] Fighting soldiers were trained (often inadequately) to follow.

Army regulations allowed field musicians to enlist at age twelve, but boys of nine and ten found their way into the ranks. Few could read music, or even play an instrument. They learned. Some boys received training at the School of Practice on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor or Newport Barracks in Kentucky. Musicians memorized Charles S. Ashworth’s A New, Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating or Elias Howe’s School for the Fife.[7] In 1862, the army adopted George B. Bruce and Daniel Decatur Emmett’s The Drummers and Fifers Guide).

Three drummer boys received the Congressional Medal of Honor. The youngest was eleven-year-old drummer Willie Johnston of the 3rd Vermont Infantry. Johnny Clem, the “drummer boy of Chickamauga,” ran away from home at age nine and became a drummer boy with the 22nd Michigan Infantry. He retired as a major general in 1916.[8]

Instruments were of three types: brass, wooden fifes, and drums. Brass-playing musicians used either keyed (that is, with keys like a clarinet) or valve bugles. (Both technologies were invented in the first decades of the 19th century.) Despite the growing popularity of brass instruments, because they were handcrafted, the total annual production before 1860 was only a few thousand. That changed with the introduction of interchangeable parts. By war’s onset, factories could produce hundreds of brass instruments weekly. Fifes (transverse flutes with six to eight holes) were generally made of rosewood or some other hardwood. They were generally tuned to the key of B-flat major. Playing in tune was unlikely at best. Field drums were tuned by a rope tension system and used four to six animal-gut snares. Drum shells were generally made of maple, ash, or holly. According to Union army guidelines, military drums were to be painted with the arms of the United States on a field that was blue for the infantry and red for the artillery. Company and regiment letters and numbers were often placed beneath the arms or in a scroll.[9]

Concert Bands

There were many important concert bands and renowned band leaders. Irish-born bandleader and cornetist Patrick Gilmore was one of the best. In October 1861 Gilmore and his entire 68-member band (including twenty drummers and twelve buglers) enlisted in the 24th Massachusetts Volunteers. The band concertized nightly, with a repertoire ranging from operatic overtures, to marches and waltzes, to songs by Stephen Foster. Equally important was New York City’s Dodworth family, which organized generations of bands. As part of their military duties, Dodworth band members helped attend to the wounded at the Battle of First Bull Run. Stationed in Washington was the United States Marine Band, under the leadership of clarinet virtuoso Francis Scala. This ensemble, which functioned as military and social dance band, regularly performed at the White House and around the city.

Emulating European ensembles, American drill teams became popular before the war. The best drill band was directed by Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, who has the unfortunate distinction of being the first Union officer to be killed during the war. Ellsworth modeled his ensemble (in both looks and marching style) on the French colonial army in Algeria (baggy pants and short jackets, fezzes and gaiters). One of Ellsworth’s many imitators was the Collis Zouaves, attached to the 114th Pennsylvania.

There were fewer Confederate bands than Union bands. This was because there were fewer available musicians and instruments, and a greater demand for fighting soldiers. The most famous Confederate ensemble was the Stonewall Brigade Band, attached to General Jackson’s First Brigade, Army of the Shenandoah. In late 1862, below Fredericksburg and along the Rappahannock River, the band alternated concert pieces with Federal bands on the opposite shore. The band remained active after the war, including performing at Grant’s funeral in 1885. As late as 1900, six members of the Civil War era configuration continued to play in the band. The band still performs today and retains the original Civil War-era instruments. Also prominent was the 26th North Carolina Regiment band, directed by Samuel T. Mickey. The band’s repertoire included Irish traditional songs, selections composed in honor of Confederate regiments and officers, and transcriptions from Italian, French, and German operas. The band was captured outside Richmond on April 5, 1865.

Instrumentation varied. Musicians made do with whatever instruments were available. These accommodations do not mean there was no sense of what an ideal instrumental arrangement might consist, however. Generally accepted was the format outlined in Dodworth’s Brass Band School, an instructional book that included band arrangements. Dodworth asserted that bandsmen should strive for balance across the instrumental range, which he divided into six categories: soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, bass, and contrabass. An ideally balanced ensemble of four brass players would include E-flat soprano, B-flat alto, tenor, and bass. As the ensemble’s size increased, instrumentation additions would solidify important timbres, expand pitch range, and fill in gaps. A six-member ensemble would double the soprano and tenor. Should a seventh instrument be added, it would be a contrabass.[10]

Bands had a distinctive sound. The period’s brass instruments used conical-bored tubing, which produced a mellower tone than today’s mostly cylindrical-bored instruments. Sometimes bells faced forward, or up, or back. Backward-facing bells were favored for marching; the cavalry preferred backward- or upward-facing bells. Mouthpieces on some instruments could swivel to direct the bell over the shoulder or upwards.

Melodies were generally played by the first E-flat soprano cornet, perhaps doubled at the octave with a B-flat cornet. Bass lines followed chord roots and were often doubled by E-flat and B-flat horns, either in unison or at the octave. Chord progressions were simple, rarely venturing past tonic, subdominant, and dominant relationships.

Band members often served in the field hospitals during combat. But not always. Many officers kept bandsmen playing because they found music braced the soldiers. Remembered James P. Sullivan of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteers, “Gettysburg came in sight and our lads straightened up to pass through in good style, and the brigade band struck up the “Red, White and Blue,” when all at once hell broke loose in front. The cavalry had found the Johnnies and they were driving them back on us. The band swung out to one side and began “Yankee Doodle” in double quick time and “Forward, double quick,” sang out the colonel.[11] Many were rushing to their deaths.

In combat, band performances were a regular feature. They might play polkas, waltzes, hymns, marches, or national airs, even with shells exploding all about. Other times, musicians were ordered to put down their instruments and serve as stretcher bearers or assist in the field hospitals. When bands played, the usual purpose was to encourage (or console) their own soldiers. At Gettysburg, for example, a Confederate band played “Nearer My God to Thee” as the soldiers retreated following Pickett’s failed advance. Sometimes, however, music was used to deflate, even confuse, the enemy. Near war’s end, music of Confederate bands helped cover the Army of Northern Virginia’s nighttime evacuation of Richmond. Unaware of the ruse, “Federal musicians responded . . . with national airs until the night was filled with melody.”[12] The “concert” continued until only a Confederate picket line remained in place.

Sometimes, bands simply entertained. Confederate soldiers gathered on a bridge on the Rappahannock River to listen to a Union band before the Battle of Fredericksburg. Colonel James C. Nisbet of the 66th Georgia wrote in his memoirs of a Confederate cornet player along the Kennesaw Mountain line who was much appreciated by the Yankees:

[He] was the best I have ever heard. In the evening after supper he would come to our salient and play solos. Sometimes when the firing was brisk, he wouldn’t come. Then the Yanks would call out: “Oh, Johnnie, we want to hear that cornet player.”

We would answer: “He would play, but he’s afraid you will spoil his horn!”

The Yanks would call out: “We will stop shooting.”

“All right, Yanks,” we would reply. The cornet player would mount our works and play solos from the operas and sing “Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming,” or “I Dreamt that I Dwelt in Marble Halls,” and other familiar airs. He had an exquisite tenor voice. How the Yanks would applaud! They had a good cornet player who would alternate with our man.[13]

Sometimes bands shared; sometimes they competed. Historian Bruce Catton wrote of Union bands performing along the Rappahannock River in the winter of 1862-1863 when, after a concert that included both “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Dixie,” 150,000 men from opposing armies on both sides of the river choked back tears and sang “Home, Sweet Home!”[14] Asbury L. Kerwood of the 57th Indiana Volunteers wrote of a night in which a Union band played “national airs” from the parapets of Fort Wood outside Chattanooga. A Confederate band followed with “Dixie.” “Instantly our own musicians took up the same tune, and when it was finished, a yell went up from our lines, followed by a ‘bah’ from the rebels.”[15]

Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart went out of his way to recruit singers and instrumentalists into his command. Stuart kept a string band with him in the field. Minstrel performer and banjoist Sam Sweeney served as his personal musician. His servant played the bones.[16]

Weighing the various successes and failures of the army’s many bands, Congress decided relatively early on (and probably incorrectly) that the costs of music generally eclipsed the benefits. The July 17, 1862 bill slashed music expenditures. General Order 91 of July 29, 1862, reduced band leaders’ pay from $105.50 to $45 monthly. Bands were eliminated at the regimental level and reassigned at the brigade level (approximately every four regiments). General Order 91 may have eliminated some three hundred bands from service.

Concert Music

Classical music entrepreneurs were worried as the 1861-62 concert season approached, but needlessly so. Pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk found ample audiences to host nearly 100 recitals over the course of the war in New York City alone, and more than 1,000 across the North, from major cities to hamlets.

Careful to offer something for everyone and anyone, the impresario Bernard Ullman, opened the New York 1861-62 concert season with German magician Carl Herrmann and his wife Rosalie (who entertained as singer, pianist, and clairvoyant). Also on the bill was Theodore Thomas and his orchestra, which performed works of Mendelssohn, Wagner, and others. Herrmann and company were a hit, enough tickets to rationalize keeping open the 4,000-seat Academy of Music on 14th Street. Chamber concerts presented in smaller venues were common, often given by members of the New York Philharmonic or touring ensembles.

Choral societies were active throughout the war. The New York Liederkranz was one of some twenty German Männerchöre (male choruses) active in New York City. The Liederkranz sang with the New York Philharmonic, the Brooklyn Philharmonic, and Theodore Thomas’ orchestra. Major wartime performances included Mendelssohn’s Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Witch’s Sabbath 1861), Félicien David’s Le Désert (1862), and Niels Gade’s Comala (1863).

Many of the city’s musical events were linked to the war. “The pavement in Broadway is battered with the steady trap of pedestrians keeping step to the martial strains of military bands leading new-fledged warriors to the field of glory; and the possible widows of these same warriors begin to excite attention,” wrote a reporter.[17] Colonel Louis Blenker’s First German Rifle Regiment held a Grand Military Festival to benefit the regiment’s families. George Frederick Bristow led a festival at the Academy of Music. Harvey Dodworth’s outdoor concerts in Central Park attracted audiences in the tens of thousands. Patriotism drove these events. In parks and theaters alike, participatory singing of nationalistic songs was a surefire winner.

While the war was good business for military bands, it was not so clear how symphonic music (including the New York Philharmonic, founded in 1842) would fare, especially if it tried to fill the Academy of Music. So for the 1861-62 season the orchestra moved to the far smaller (and less expensive) Irving Hall. After two sold-out seasons, the orchestra returned to the Academy.

Opera thrived. Staged in the fall 1862 were Weber’s Der Freischütz, Bellini’s La Sonnambula and Norma, and Verdi’s La Traviata and Il Trovatore. During the 1863-64 season, over twenty-five different operas were scheduled at the Academy of Music alone.

Yet, whatever opera’s successes, it was low-brow shows in “concert saloons” that attracted the biggest audiences. Black-face minstrel shows were most popular of all, especially Bryant’s Minstrels, with Daniel Emmett in the group. New York Tribune editor and abolitionist Horace Greeley was frequently targeted by minstrel troupes. So was opera. Meyerbeer’s Dinorah, ou Le Pardon de Ploërmel was recast in blackface as Dinah—The Pardon Pell-Mell. Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia (the infamous daughter of Pope Alexander VI), was recast in blackface (for an 1862 Christmas holiday show, no less).

Band music was common in outdoor Washington throughout the war. In the weeks and months following the attack on Fort Sumter, arriving regiments from states ranging from Massachusetts to Minnesota paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue. Scala led the Marine Band at official events; the ensemble gave regular summer concerts on the south lawn of the White House.

Lincoln attended the opera nineteen times during his presidency. But musicians often came to him. Programs at the White House were frequent. Song recitals were given by the Native American Larooqua (billed as the “aboriginal Jenny Lind”) and Meda Blanchard. Venezuelan child prodigy pianist Teresa Carreño also performed, as did the Connecticut-based abolitionist vocal group the Hutchinson Family Singers.

Music-related Commerce

Music Publishing, South and North

After secession, Southern publishers were no longer bound by Union copyright laws. Profit margins on existing inventory increased. And of course, the Confederacy required songs of its own. Southern publishers included the Charleston, South Carolina-based Siegling Music Company (America’s oldest), and in New Orleans Philip P. Werlein’s company (the first Southern firm to publish a version of “Dixie”) as well as the Blackmar brothers, who published “The Bonnie Blue Flag” and “Maryland! My Maryland!”[18] But with the April 1862 fall of New Orleans, Confederate music publishing in New Orleans effectively came to an end. Werlein was shut down; most of his inventory was confiscated.[19] The Blackmars moved to Augusta, Georgia, where they published more than 200 additional compositions. The Macon, Georgia-based firm of Schreiner & Son published 121 works during the war. As the war progressed, Southern paper and ink became scarce, inflation soared.

The most successful Civil War music publisher was Root & Cady, founded in Chicago in 1858. Just three days after the war’s beginning, the firm published a response to Fort Sumter with “The First Gun Is Fired! May God Protect the Right,” written by George Frederick Root, the co-owner’s brother. Within five weeks, four more war-related songs were published. Three were written by G. F. Root, who would also write “Battle Cry of Freedom,” perhaps the war’s most successful song. In addition to G. F. Root, Root & Cady published songs by Henry Clay Work, who wrote the 1862 minstrel-style “Kingdom Coming (Year of Jubilo)” (1862), “Come Home, Father” (1864), and “Marching Through Georgia” (1865). Root & Cady would publish about eighty war-related compositions.

Another publisher was the Boston-based firm of Oliver Ditson & Co. Ditson’s wartime publications included “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground,” and “We Are Coming Father Abra’am.”

To meet the demand for parlor music, a wealth of generic intermediate-level piano scores was published North and South. Not much of the music was memorable, but the cover art was often remarkable. Much music carried war-related titles, including: “Major Anderson’s Grand March” (1861), “Maryland My Maryland with Brilliant Variations for the Piano” (1863), “Hope on—hope ever! Brilliant Variations on Henry Tucker’s Beautiful Song When This Cruel War Is Over” (1863), “Bonnie Blue Flag with Brilliant Variations” (1863), as well as many “battle” pieces, like “Battle of Port Royal” (1861), “The Battle of Roanoke Island: Story of an Eyewitness” (1862), “Battle of New Orleans” (1862), and “Battle of Fort Donelson” (1862), and many more.[20]

Songs

“The Bonnie Blue Flag,” one of the South’s most popular songs, was written by English-born vaudevillian Harry Macarthy, shortly after South Carolina’s secession. The words were new; the melody was not (the melody came from the Irish air “The Irish Jaunting Car”). This was just the first of many Southern songs focused on the flag, including: “The Flag of Secession” (sung to the melody of “The Star Spangled Banner,” (no date), “The Flag of the Free Eleven” (1861), “Confederate Flag” (1861), “The Stars of Our Banner” (1861), “The Flag of the South” (1861), “The Confederate Flag” (1861), and more.

Not surprisingly, “Bonnie Blue Flag” was reviled in the North. The Union’s General Benjamin Butler found it particularly loathsome. When Butler’s army occupied New Orleans, he arrested the song’s publisher, A. E. Blackmar. Butler also threatened a $25 fine to anyone caught whistling the melody.[21]

The Confederate song “My Maryland” was born in response to an April 19 encounter between raw Union troops and a pro-Confederate mob on the streets of Baltimore. News of the Baltimore incident stirred sympathizers throughout the Confederacy. In response, James Ryder Randall (1839-1908), a native Marylander then based in New Orleans, wrote the poem “My Maryland,” which was published in the New Orleans Delta. Baltimore sisters Jennie and Hetty Cary added “My Maryland!” to each stanza and the poem was fit to the old German folk tune “Lauriger Horatius” (“Oh, Tannenbaum”).

In the North, although Root’s previously mentioned “Battle Cry of Freedom” and Work’s “Kingdom Coming” were probably the most successful songs, there were many more, including six settings of the poem “We Are Coming, Father Abraham,” which first appeared anonymously in New York’s Evening Post on July 16, 1862. The poem was set to music by master composer Stephen Foster and Patrick Gilmore, but the most popular was L. O. Emerson’s, which sold some two million copies.

Many song topics divided neatly into North or South, such as the songs published in honor of officers, particularly charismatic generals. The music-loving Stuart and the musically ambivalent Jackson garnered at least half-a-dozen titles each.

Numerous anti-war songs were published in the war’s first years. Living in a border state, Kentucky-based journalist and Unionist Will Shakespeare Hays composed “Let Us Have Peace” Perhaps the most successful anti-war song in both North and South was Hewitt’s “All Quiet Along the Potomac To-night” (1862), the best of many settings of Mrs. Ethel Lynn Eliot Beers’ 1861 anti-war poem “The Picket Guard.” Bathos ruled in a series of 1862 anti-war songs, including: “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground,” “The Vacant Chair,” and “Weeping, Sad and Lonely; or, When This Cruel War Is Over.”

Themes of death, often death without glory, permeated songs in the war’s middle years. Mother, home, and hearth were also recurrent themes. 1863 saw the publication of “Break It Gently to My Mother,” “Dead on the Battle Field,” “The Dying Volunteer,” “Dear Mother I’ve Come Home to Die,” “Who Will Care for Mother Now,” “Be My Mother ’Till I Die,” “The Dying Mother’s Advice to Her Volunteer Son,” “The Soldier’s Home,” and “My Boy Is Coming from the War” (he will not), and Root’s 1864 songs “Just Before the Battle, Mother” and “Just After the Battle.”

Near war’s end came new emotional tones. A budding optimism, was reflected in songs like “Coming Home from the Old Camp Ground,” “The Boys in Blue Are Coming Home,” “The Boys Are Marching Home” (1865), and “Charleston is Ours!” Sung for decades after war end in the North, though despised in the South, was Henry Work’s “Marching Through Georgia.” Northern resentment was common as well, as with the vindictive “Dixie’s Nurse,” “Jeff in Petticoats,” “Jeff Davis in Crinoline,” “A Confederate Transposed to a Petticoat,” “The Sour Apple Tree; or, Jeff Davis’ Last Ditch,” and “How Do You Like It Jefferson D?” Though now mostly forgotten, dozens of songs and marches were composed in response to Lincoln’s assassination.

Also popular North and South were songs of the British Isles, including the sentimental ballad, “Annie Laurie” (written in the late 1600s), “Home Sweet Home” (1823), and “Kathleen Mavourneen” (c. 1835-38). One of the war’s silliest songs was decidedly home grown, “Goober Peas,” This paean to the peanut was written by A. E. Blackmar but published under a pair of pseudonyms. P. Nutt, the composer; A. Pender, the lyricist,

Singing Soldiers

“The men who wore the blue, and the butternut Rebs who opposed them, more than American fighters of any period, deserve to be called singing soldiers,” observed historian Bell Irvin Wiley.[22] In camp, common soldiers told stories and made music with violins and guitars, fifes and bugles, drums and bones, or any instruments they might have made or brought with them from home. Sometimes the soldiers danced or presented theatrical performances. Minstrel songs were popular, so were sentimental ballads. For prisoners, music not only offered relief from depression, but offered a platform for acts of solidarity and defiance.

Aware that soldiers would remember melodies but might forget words, publishers printed dozens of songsters, books of lyrics alone. Southern songsters included The Southern Flag Song Book (1861), The Dixie Land Songster (1863), Virginia Songster (1863), Stonewall Song Book (1864), The Army Songster (1864), The Beauregard Songster (1864), The Rebel Songster (1864), Songs of Love and Liberty (1864), and The Gen. Lee Songster (1865). Northern songsters included the Stars and Stripes Songster (1861), The Flag of Our Union Songster (1861), Tony Pastor’s New Union Song Book (1862), The Little Mac Songster (1862), Bob Hart’s Plantation Songster (1862), The Frisky Irish Songster (1863), War Songs for Freemen (1863), John Brown Songster, Christy’s New Songster and Black Joker (1863), and The Campfire Songster (1864).[23]

Music for religious revivals stirred northern and southern armies, especially during the winter months, when fighting lagged or stopped altogether. Many recollections can found of prisoners of war resisting in one of the few ways possible, though song.

African-American Music

African-American musical and dance styles had been parodied by blackface minstrels since the 1830s, but it was not until the Civil War that most Northern whites began to have direct contact with, and take serious notice of, the real music of African Americans.

A major African-American genre was the spiritual. Spirituals were based on biblical verses, of course. But often imbedded within those ancient images were ones of secular freedom. The spiritual “Go Down Moses,” for example, invites comparisons between the fate of the ancient Israelites and the oppression of the African-American slaves. “Go Down Moses” was one of the first spirituals that become known to a white Northern audience, when in October 1861 the first stanza was printed in the New York-based newspaper, National Anti-Slavery Standard.[24] In December, more verses were published in The Burlington Free Press.[25]

Urban white Northerners had been aware of African American virtuosos, but they mostly knew those who conformed to Euro-American musical styles, such as band master Frank Johnson (1792-1844), concert vocalist Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield ca. 1824-1876 (aka., the Black Swan), and Connecticut’s Lucas Family Singers, who occasionally sang with the Hutchinson Family Singers.

The Civil War emancipated African-American music. In the North, escaped slaves sought, and generally received, protection under Union armies. What were the soldiers hearing? A September 1861 Dwight’s Journal of Music account from Fortress Monroe, entitled Contraband Singing, gives an idea:

“It is one of the most striking incidents of this war to listen to the singing of the groups of colored people in Fortress Monroe. …The hymn was long and plaintive, and the air was one of the sweetest minors I have ever listened to… All was as tender and harmonious as the symphony of an organ.”[26]

Such experiences must have been sobering. Absent were Jim Crow and Zip Coon, and all of the sensibilities that decades of blackface minstrel shows had taught Northern white audiences to expect.

Northerners were also traveling into the slave South. Most were soldiers, but detailed reports come from relief workers, teachers, collectors, and journalists. Beginning in 1862, white and African-American northerners worked with contrabands and newly enlisted Union soldiers in South Carolina, where Union forces had captured Port Royal Sound and freed some 10,000 slaves. From there came some of the war’s most intriguing musical documents: the diaries of Charlotte Forten (an African-American teacher from Salem, Massachusetts, who worked on Helena Island from 1862 to 1864; Slave Songs of the United States (1867), by William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison; and Army Life in a Black Regiment (1867), by Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson. [27]

In January 1866, just months after war’s end, the Fisk Free Colored School (soon to be renamed Fisk University) opened in Nashville, on the site of a former Union army hospital. Five years later, George L. White would lead the Fisk Jubilee Singers on a fund-raising tour. The choir followed the path of the Underground Railroad northward through Ohio, then east to The White House, where they performed for President Grant. From there they went to New York City’s Steinway Hall, and eventually to Europe. Initially, the group sang Euro-American songs and anthems, but they included a Negro spiritual as an encore. The encore proved so successful that African American repertoire soon took front and center. So, albeit almost accidentally, began the world-wide dissemination of African American music.

Conclusion

Music flowed freely across political boundaries and army lines. Northerners and Southerners sang the same songs, Confederate and Union armies sometimes marched to the same melodies. In the evenings, songs of home and faith floated across military encampments. By day, the stern commands of drums and bugles pierced battlefields. Away from the front, bands entertained in city streets and parks, orchestras and choirs filled concert halls, and sentimental songs enlivened parlors. Music’s resonance gave voice to an era. Always, music bound people together, helped them move forward, and helped them to remember.

- [1] Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, The Passing of the Armies: An Account of the Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, Based upon Personal Reminiscences of the Fifth Army Corps, University of Nebraska Press 1998 ed. (New York and London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons 1915), 261. The full text of the 1915 edition is available at https://archive.org/details/passingofarmiesa00cham/page/n9 , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [2] Kenneth E. Olson, Music and Musket: Bands and Bandsmen of the Civil War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981), 21. Quote taken from John J. Pullen’s The Twentieth Maine. (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1957).

- [3] Francis Alfred Lord and Arthur Wise, Bands and Drummer Boys of the Civil War (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1966), 30.

- [4] For a more extended analysis, see William Bufkin, Union Bands of the Civil War (1861-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis, 2 vols. (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1982), 1:27-29. See https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3522&context=gradschool_disstheses , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [5] Ibid., 165.

- [6] Frank J. Rauscher, Music on the March: 1862–’65 With the Army of the Potomac (Philadelphia: Wm. F. Fell & Co., 1892), 69. The full text of the book is available at: https://archive.org/details/musiconmarch186200raus/page/n5 , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [7] Charles S. Ashworth, A New, Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating (Boston: Published by the Author, 1812); Elias Howe, Howe’s School for the Fife (Boston: Oliver Ditson & Co., 1851); George B. Bruce and Dan D. Emmett, The Drummers’ and Fifer’ Guide (New York: Firth, Pond & Co., 1862).

- [8] Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), 297-8.

- [9] Robert Garofalo and Mark Elrod, A Pictorial History of Civil War Era Musical Instruments & Military Bands (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1985), 36.

- [10] Allen Dodworth, Dodworth’s Brass Band School (New York: H. B. Dodworth & Co., 1853), 11-12. The full text of the book is available at: https://archive.org/details/musiconmarch186200raus/page/n5 , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [11] James P. Sullivan, An Irishman in the Iron Brigade: The Civil War Memoirs of James P. Sullivan, Sergt., Company K, 6th Wisconsin Volunteers, William J.K. Beaudot and Lance J. Herdegen, eds. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1993), 93-94.

- [12] Rembert W. Patrick, The Fall of Richmond (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1960), 36.

- [13] James Cooper Nisbet, Four Years on the Firing Line (Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing Company, 1991), 204.

- [14] Bruce Catton, Mr. Lincoln’s Army (Garden City: Doubleday and Company, 1962), 178.

- [15] Cited in Bufkin, Union Bands, 100, from Asbury L. Kerwood’s Annals of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment Indiana Volunteers (Dayton: W.J. Shuey, 1868), 216.

- [16] The bones is a hand-held percussion instrument generally made of a matched pair of rib bones or curved hardwood slats. Today, players often use spoons instead.

- [17] In, Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Strong on Music: The New York Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, 3 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 3: 436.

- [18] Richard Barksdale Harwell, Confederate Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1950), 8-10, 42-43.

- [19] Ibid., 10-11.

- [20] For examples of cover art on Civil War sheet music see the Library of Congress’ Civil War Sheet Music Collection at https://www.loc.gov/collections/civil-war-sheet-music/ , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [21] Willard A. Heaps and Porter W. Heaps, The Singing Sixties: The Spirit of Civil War Days Drawn from the Music of the Times (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 57.

- [22] Wiley, Billy Yank, 157.

- [23] For an example of these songsters see The Dixie Land Songster (Augusta. GA: Blackmar & Bro, 1863) at https://archive.org/stream/dixielandsongste01maco#mode/2up , accessed November 30, 2018. For a list of songsters collected at the Brown University Library see https://library.brown.edu/collections/harris/songst.php , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [24] Anti-slavery publications began in 1821 with Benjamin Lundy's newspaper, Genius of Universal Emancipation. Other anti-slavery papers included, among numerous others; William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator, Frederick Douglass' North Star, Julia Ward Howe and Samuel Gridley Howe's Commonwealth, Elijah P. Lovejoy's St. Louis Observer, Lydia Maria Child's National Anti-Slavery Standard, and John Greenleaf Whittier's Pennsylvania Freeman.

- [25] The Burlington Free Press (Burlington VT), December 13, 1861 at https://www.newspapers.com/image/73675680/?terms=%22Go%2BDown%2BMoses%22 , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [26] Dwight's Journal of Music, September 7, 1861, 182, at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003928160 , accessed November 30, 2018.

- [27] “A Social Experiment: The Port Royal Journal of Charlotte L. Forrten, 1862-1863,” in The Journal of Negro History 35, no. 3 (July 1950):233-64, at http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/african-americans/Forten.pdf , accessed November 30, 2018; William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison, Slave Songs of the United States (New York: Peter Smith, 1951) at https://archive.org/details/slavesongsunite00garrgoog/page/n6 , accessed November 30, 2018; Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment (Boston: Fields, Osgood, & Co., 1870), at https://archive.org/details/armylifeinblackr00higg_0/page/n9 , accessed November 30, 2018.

If you can read only one book:

McWhirter, Christian. Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Books:

Allen, William Francis, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware. Slave Songs of the United States. New York: A. Simpson & Company, 1867.

Bakeless, Katherine Little. Glory, Hallelujah: The Story of The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 1944.

Bardeen, Charles William. A Little Fifer’s War Diary. Syracuse, NY: C. W. Bardeen, 1910.

Bernard, Kenneth A. Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1966.

Bruce, George B. and Daniel D. Emmett. The Drummers’ and Fifers’ Guide. New York: Firth, Pond & Co., 1862.

Bufkin, William. Union Bands of the Civil War (1861-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis, 2 vols. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1982.

Cornelius, Steven. Music of the Civil War Era. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Currie, Stephen. Music in the Civil War. Cincinnati, OH, Betterway Books, 1992.

Davis, James A. Music Along the Rapidan: Civil War Soldiers, Music, and Community during Winter Quarters, Virginia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Dodworth, Allen. Dodworth’ s Brass Band School. New York: H. B. Dodworth & Co., 1853.

Epstein, Dana J. Music Publishing in Chicago Before 1871: The Firm of Root and Cady. Detroit, MI: Information Coordinators, Inc., 1969.

Garofalo, Robert and Mark Elrod. A Pictorial History of Civil War Era Musical Instruments & Military Bands. Charleston, WV: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1985.

Gottschalk, Louis Moreau, Clara Gottschalk, ed., Robert E Peterson, trans. Notes of a Pianist. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1881.

Hall, Harry H. A Johnny Reb Band from Salem: The Pride of Tarheelia. Raleigh: The North Carolina Confederate Centennial Commission, 1963.

Harwell, Richard Barksdale. Confederate Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1950.

Heaps, Willard A. and Porter W. Heaps. The Singing Sixties: The Spirit of Civil War Days Drawn from the Music of the Times. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth. Army Life in a Black Regiment. Boston: Fields, Osgood, & Co., 1870.

Keck, George R. and Sherrill V. Martin, eds. Feel the Spirit: Studies in Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Music. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Lawrence, Vera Brodsky. Music for Patriots, Politicians, and Presidents. New York, McMillan, 1975.

———. Strong on Music: The New York Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, 3 vols., vol.3: “Repercussions 1857-1862”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Mahar, William J. Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. Champaign, University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Meyers, Augustus. Ten Years in the Ranks U.S. Army. New York: The Stirling Press, 1914.

Olson, Kenneth E. Music and Musket: Bands and Bandsmen of the American Civil War. New York: Greenwood Press, 1981.

Rauscher, Frank. Music on the March 1862-’65 With the Army of the Potomac. Philadelphia, PA: Press of Wm. F. Fell & Co., 1892.

Silber, Irwin. Songs of the Civil War. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth Century America. New York, Oxford University Press, 1974.

Organizations:

Library of Congress

The Civil War Sheet Music Collection at the Library of Congress.

Brown University

The Sheet Music Collection at Brown University includes numerous entries for the Civil War.

Duke University

The Historic Sheet Music Collection at Duke University includes numerous entries for the Civil War.

Web Resources:

At the Library of Congress website search “Civil War Music” for dozens of sources of information on Civil War music.

John Sullivan Dwight published Dwight’s Journal of Music, an influential musical periodical, weekly from 1852 to 1881.

The website of the 26th North Carolina Regimental Band includes a history of this group.

American Civil War Music (1861-1865) provides a long list of Civil War era songs and includes downloadable .midi files and text documents of the lyrics for each song.

This is the American Battlefield Trust’s article on Civil War Music, The Music of the 1860’s”.

The Imaginative Conservative: Top Ten Civil War Songs provides a history of the ten songs they have identified as well as a video for each.

AmericanCivilWar.com provides a brief introduction to Civil War music and identifies a dozen or so CDs of Civil War songs which can be purchased from various sources.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.