Civil War Statistics

by Thomas R. Flagel

Numeric analysis remains one of the sharpest tools within the workshop of social science for interpreting the Civil War. Statistical methodology can provide fresh perspective on existing views. Likewise, examining how historical actors gathered and interpreted statistics in the past can help us understand how their perceptions were formed. The realm of statistical analysis of the Civil War is enormous. This essay examines several issues through the lens of statistics including fatalities, enslavement, weaponry, communications, the conflict as an international phenomenon, economics, and postwar memorialization. One hundred and fifty years after the war modern researchers have enormous (and growing) amounts of information available to them. And the task of gathering and analyzing the data to inform modern audiences and for a better understanding of how the war’s participants were influenced by the data available to them is also enormous.

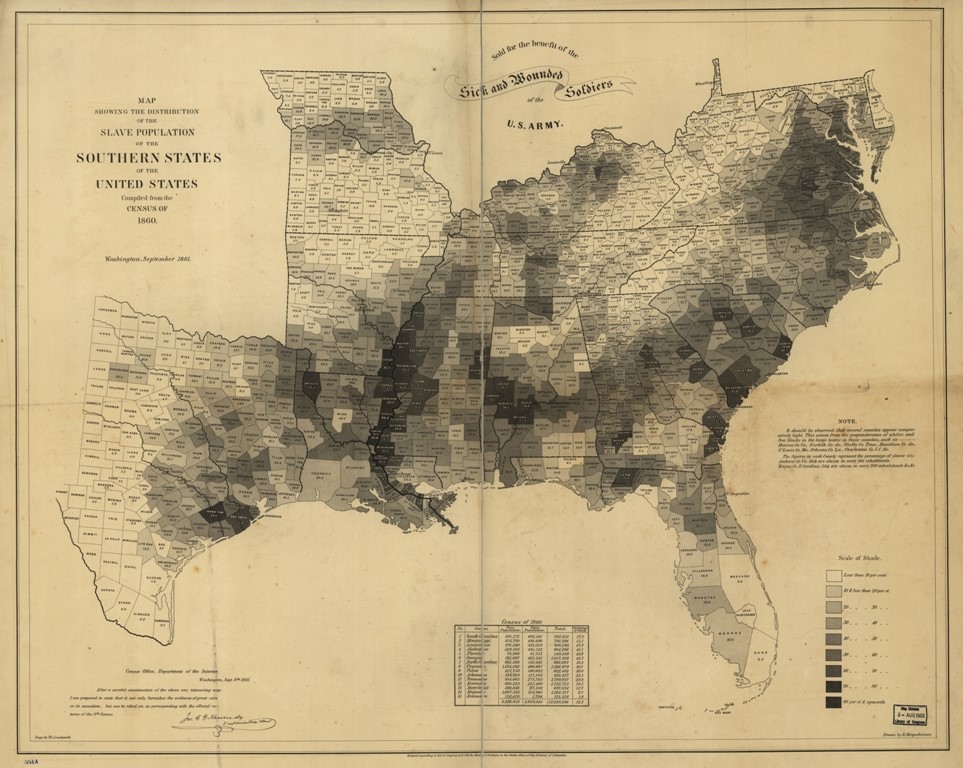

Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the southern states of the United States. Compiled from the census of 1860 published by Henry S. Graham 1861.

Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LOC Control Number 99447026

While serving in the U.S. Congress, Abraham Lincoln delivered a speech endorsing governance using statistics. “In that information,” he proclaimed, “we shall have a stern, unbending basis of facts—a basis, in nowise subject to whim, caprice, or local interest.” The longtime reader of Euclid further insisted, “statistics, will save us from doing, what we do, in wrong places.”[1] Conversely, mere numbers are just as capable of creating ambiguity and disconnection, as Clara Barton famously stated in 1864 while watching regiments of infantry march through Washington, D.C.: “Man has no longer an individual experience,” she lamented,” but is counted in thousands and measured in miles.”[2] Thus the paradoxical effect of examining the American Civil War through the lens of statistics; it can clarify and blur simultaneously.

Yet numeric analysis remains one of the sharpest tools within the workshop of social science. The methodology can provide fresh perspective on existing views. Likewise, examining how historical actors gathered and interpreted statistics in the past can help us understand how their perceptions were formed.

Following are a selection of topics relating to the Civil War, among potentially innumerable ones, and their respective relationships with statistics. Statistics relating to the Civil War are innumerable; the following covers some of the most significant.

Fatalities

One of the most ubiquitous topics in Civil War studies, especially concerning the search for numbers, involves the death toll of the conflict itself. In this case, as it is with most questions mathematical, Union sums are frequently easier to calculate than Confederate. Greater access to paper, ink, presses, and a far larger clerical workforce turned the Federal war effort into a vast factory of documentation. Concerning the tally of deceased, the Union also had the advantage of a formal inventory and warehousing system—National Cemeteries. In 1862, the war’s unforeseen escalation prompted Congress to authorize a new entity, the National Cemetery Administration. Initially planning that no more than a dozen would be required, by war’s end the Federal government needed 73 of them.

The process of gathering and concentrating their widely dispersed dead enabled the Federal government to conduct a comprehensive audit, a venture not possible for the disintegrating Confederacy. Consequently, nearly 85% of all Union dead are interred in national cemeteries, whereas roughly 75% of Confederate fatalities were eventually interred in various city cemeteries with another 15% or so placed in church graveyards or in private family plots.[3] By 1868, as the Federal reinternment program drew to a close, the Quartermaster General’s Office calculated that their total losses were near 355,000, based on the total number of known Union internments plus an estimated 50,000 burial sites lost or unaccounted for. Without a surviving central government, the Confederate total was more elusive.[4]

Decades later, two amateur historians established a combined estimate of Union and Confederate fatalities that would stand for generations. William Fox’s Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (1889) and Thomas Livermore’s Numbers and Losses in the Civil War (1900) contended the amalgam stood at or near 620,000 deaths.[5] In the early twenty-first century, rapidly accelerating computer capabilities and document digitization invited recalculations. Among the more recognized is J. David Hacker’s “A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead” (2011), wherein he posits that the previous summation was almost certainly too low, and a figure of 850,000 is within the realm of possibilities. Hacker’s work generally confirms James McPherson’s conservative estimate of 50,000 total civilian deaths. Jim Downs’ Sick from Freedom (2012) augments Hacker’s exploration of African American “contraband” fatalities, with Downs estimating the number certainly reached into the tens of thousands. Notably, Hacker finds one demographic that experienced almost no alteration of its mortality rate between peace and wartime – southern white women between ages 10 and 44.[6]

Two main historiographic camps have evolved concerning the sum of the war’s fatalities, not about the number itself, but about interpretation of the statistic. Representing the older notion that the conflict was exceptionally deadly is Charles Royster’s 1993 Pulitzer-winning volume The Destructive War.[7] Embedded within such narratives is the argument that much of the war’s gravitas stems from its unmatched losses in U.S. military history. More recent scholarship cautions against the emphasis of body counts as the defining aspect of any given event. A leading voice is that of Mark Neely, Jr., who reminds us that perpetrators and victims alike tended to place disproportionate attention on losses.[8] McPherson among others notes that comparatively speaking, the Civil War’s effect on total populations almost pale in comparison to the destruction wrought by simultaneous conflicts in Paraguay, Taiping, and the Great Plains and Rockies of North America.[9] Nicholas Marshall adds that many historians are either consciously or subconsciously selective in their use of statistics; for example, he notes that the most common practice is to present the combined number of military deaths in the war rather than divide them into their less monumental shares for each side.[10]

Yet the ratio of loss can be considered staggering. On average, for every five citizen-soldiers who departed, only four would return alive. As Drew Gilpin Faust points out in her seminal This Republic of Suffering (2008), the loss of one person could be traumatic and potentially devastating to a family.[11] Further, over 30% of Union bodies in national cemeteries are marked as “unknown,” and the ratio of Confederate unmarked graves likely exceeds 50%, which deprived hundreds of thousands of surviving loved ones a sense of closure.[12]

More recent scholarship explores the war’s environmental impact, going beyond the human-centric view. Gene Armistead, for example, calculates that somewhere between 1.2 million and 1.5 million horses and mules perished in military service, with an average wartime lifespan of less than a year. While the artillery service statistically was one of the safer branches for humans, Armistead finds that it was likely the most lethal for equines, as their life expectancy in service dropped to about eight months.[13]

What can be challenged when examining these numbers is the liberal use of the adjective “bloody,” as the supermajority of military, citizen, and enslaved deaths were from disease.[14] Consequently, the war can be viewed as a biological calamity more than a military one, and yet a closer examination of mortality statistics complicates even this general axiom:

Leading Causes of Death (Casualty figures are approximate)

Killed in action (CSA 54,000) (US 67,100)

The chief killer was not a specific virus or bacterium but a soft-lead bullet, which accounted for over 90% of combat fatalities, and most destructive was the Minié ball. Unlike the spherical smoothbore ball, which tended to retain its shape when entering the body, the conical Minié design tended to tumble, flatten, and fragment upon impact. Amputations attested to its destructive effects on bones, but its most lethal work was on arteries and organs. Less than 5% of KIAs came from artillery, and less than 1% from edged weapons and bayonets. On average, of every hundred fatalities on a battlefield, five died from limb wounds, twelve from punctures to the lower abdomen, fifteen from damage to the heart or liver, and over fifty from lacerations to the head or neck. In all, one of every sixty-five Federals and one of every forty-five Confederates were killed in action. Of course, not all military personnel directly experienced combat, but for those who did, engagements were naturally treacherous. For example, combatants in the Battle of Shiloh stood a 1-in-26 chance of being killed in action; at Chickamauga the ratio approached 1-in-30; and at Gettysburg the chances were roughly 1-in-23.[15]

Dysentery/diarrhea (CSA 50,000) (US 45,000)

Misdiagnoses cloud any tally of illness-related fatalities, but almost certainly no maladies claimed more lives than dysentery and diarrhea. Soldiers called it the quickstep, and a large number suffered from it, many of whom were stricken several times. About one in fifty cases were fatal.[16]

Died of wounds (CSA 40,000) (US 43,700)

The war was a monument to bad timing, conducted six years after the U.S. War Department adopted the Minié ball as standard rifle ammunition and fifteen years before Josef Lister’s breakthrough work in Germ Theory. For any wounded person who made it to an aid station or hospital of any type, their troubles were just beginning. In Vietnam, one in four hundred of the wounded perished. In the Korean War, one of every fifty wounded American soldiers died of their injuries. In the Civil War, one in seven wounded Federals and nearly one in five wounded Confederates died, sometimes within minutes, sometimes after months of suffering.[17]

Typhoid (CSA 30,000) (US 34,800)

Doctors called it Camp Fever, as it erupted when humans came in prolonged contact with one another. Entering usually through the mouth via contaminated water or food, nearly one in three cases were fatal.[18]

Prison (CSA 26,100) (US 31,200)

Dysentery, diarrhea, typhoid, and pneumonia claiming most victims. Thousands more succumbed to starvation, dehydration, exposure, murder by guards, murder by fellow inmates, and suicide. Due to overcrowding, poor sanitation, and lack of provisions on both sides, more American prisoners of war died in 1864 than in any other year in U.S. history. For the war as a whole, more men died in prisons than were killed in action at Gettysburg, Chickamauga, Antietam, Wilderness, Chancellorsville, Shiloh, First and Second Manassas, Stones River, Cold Harbor, Spotsylvania, Fredericksburg, Pea Ridge, and Wilson’s Creek combined.[19]

Enslavement and the War

To what extent the Civil War “resolved” the slavery question remains debatable, but for apologists who contend that the institution was not a cornerstone of the Confederate experiment, the numbers are generally not in their favor. Common is the argument that only one in ten Confederate soldiers possessed human chattel, a calculation close to accurate. Yet with an average age of 25, most enlisted men had not yet gained inheritance or enough fiscal credit to acquire another person. Ownership came primarily in modest numbers; the average holding was six or fewer people. Still, by 1861 approximately one in eight Americans were owned by another American, comprising around $32 billion in human property (approximately $80 billion in 2018).[20]

Clara Barton’s assertion that numbers veiled the individual identities certainly applied to the enslaved, whose masters documented their existence in raw data. To speak of an “average” slave life is ambiguous at best, but all could (and often were) appraised in currency values. Toddlers could cost $100 while healthy adult males neared $2,000 (and more for highly skilled labor). Infants were long-term speculations, as nearly half did not survive to the age of two.[21] Despite high infant mortality and an average life expectancy of less than 22 years, the number of Americans in bondage quadrupled from 1800 to 1860, mostly through reproduction. Enslaved individuals were also used as currency. Transferable, used as collateral, inherited through wills, etc., they were often reallocated to cover debts, as was the case for individuals owned by Thomas Jefferson and John Tyler.[22]

For all slave states in the censuses of 1850 and 1860, populations were tabulated in county slave schedules, where each owned person almost always appeared as a number rather than a name.[23] Census statistics largely counter arguments that slavery was “dying out.” Additionally, the numbers illustrate how the spread of the institution, rather than its mere existence, was the most contentious issue of the day. The “dying out” position held some validity in Delaware and Virginia, where populations were stagnating or in decline, but the institution was spreading quickly and voluminously to the south and southwest.

For example, Georgia’s slave population in 1800 was 60,000. Thirty years later, it was 217,500. By 1860, the number had grown to 462,000, almost as many slaves as there were in all of Cuba.[24]

In 1830 Mississippi had 70,000 residents classified as property. By 1840, that numbered had tripled. By 1860, it had more than doubled again to 437,000.[25]

Alabama was a prime example of how the “Old South” was in fact very new. When it became a state in 1819, there were some 100,000 inhabitants within its newborn borders, a third of whom were listed as chattel. By war’s start, Alabama’s population had reached one million, and nearly half were legally enslaved.[26]

In 1836, there were 5,000 slaves in Texas. By the time of annexation into the U.S, the number surpassed 30,000. At secession, there were 160,000 and growing. [27]

Less than one in ten slaves were literate (mostly due to state regulations), but virtually all were taught how to count. Despite the image of plantation gang labor, most work was conducted through task labor, with daily or weekly quotas: bushels of corn, pints of turpentine, pecks of beans, leaves of tobacco, pounds of cotton. Since the quota was the main objective, most task work went unsupervised, and a proficient laborer might gain precious free time by the end of the day or week, or undergo punishments when totals weren’t reached.[28]

Work and enslaved were measured in hands. If five hands were required to harvest a field, the assigned workforce could be any combination of five full hands (healthy adult males) to twenty quarter-hands (children, the aged, and disabled). During the war, owners were paid $30 a month for each hand they supplied the Confederate Government, whereas a private in the Confederate Army received $11 or less.[29]

Slave Societies and Order of Secession

Statistical comparisons illustrate how the secession crises proceeded; states departed not according to geographic location, size, age, or respective political leverage. Each left almost in the exact order of their concentration of enslavement, as illustrated by the following. Notably, all states with an enslaved percentage =/<20% (Kentucky at 20%; Maryland at 13%; Missouri at 10%; and Delaware at 2%, and all free-soil states) did not secede. Hence, 20% can be argued as the threshold at which an antebellum U.S. state was a slave society or a society with slaves.

South Carolina Percentage enslaved: 1st (57.1%)

Order of secession: 1st (Dec. 20, 1860)[30]

Mississippi Percentage enslaved: 2nd (55.1%)

Order of secession: 2nd (Jan. 9, 1861)[31]

Georgia Percentage enslaved: 3rd (48.2%)

Order of secession: 5th (Jan. 19, 1861)[32]

Louisiana Percentage enslaved: 4th (46.8%)

Order of secession: 6th (Jan. 26, 1861)[33]

Alabama Percentage enslaved: 5th (45.1%)

Order of secession: 4th (Jan. 11, 1861)

Florida Percentage enslaved: 6th (43.9%)

Order of secession: 3rd (Jan. 10, 1861)[34]

North Carolina Percentage enslaved: 7th (33.3%)

Order of secession: 10th (May 20, 1861)[35]

Virginia Percentage enslaved: 8th (30.9%)

Order of secession: 8th (April 17, 1861)[36]

Texas Percentage enslaved: 9th (30.2%)

Order of secession: 7th (Feb. 1, 1861)[37]

Arkansas Percentage enslaved: 10th (26.0%)

Order of secession: 9th (May 6, 1861)[38]

Tennessee Percentage enslaved: 11th (25%)

Order of secession: 11th (June 8, 1861)

Formation of the Confederate States of America

At Montgomery, the provisional government began as fifty delegates from the original seven states. Statistically, they were not a representative sample of their constituency. All were adult, white, male, formally educated. Of the fifty-five members of the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, 25% owned slaves. Of the fifty members of the Confederate convention, 98% were slave owners. Forty-eight of the fifty men were born in slave states, and thirty-three listed their profession as “planter.”[39]

After a committee of twelve created a new Constitution (based largely on the one they left but with some notable changes), the convention eventually and unanimously accepted the new constitution. When determining the number of representatives to be apportioned per each state’s population, the Confederate version altered the “three-fifths of all other Persons” clause to read “three-fifths of all slaves.” Whereas the U.S. Constitution never directly used the word “slave,” the Confederate version used the terms “slave” or “slavery” a total of ten times, most notably in Article I, Section 9, where it forbade states the right to pass any legislation “denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves.”[40]

Rate of Slave Escapes

Despite great attention heaped upon the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, bounty hunters, personal liberty laws, and the Underground Railroad, the total number of successful slave escapes during the antebellum period likely did not exceed 1,000 individuals per year, or around 0.025% of the enslaved. During the war, likely only 10% of the four million enslaved ever reached liberation, and yet by comparison the later rate was explosive. By the end of 1862, with Union armies making deep inroads into Confederate states in the Western Theater, the speed of escape went from one thousand per annum to approximately one thousand per month. By the end of 1863, with hundreds of Union fortifications and forays reaching ever farther into the Southern interior, the rate climbed to one thousand every two to three days.[41]

Again, statistics illustrate how emancipation involved a fraction of the enslaved, and most of those were liberating themselves from bondage. As the numbers attest, Lincoln’s Proclamation was more a reactive than proactive to what was occurring on the ground.

Weaponry

A testament to the accelerating Industrial Revolution, the American Civil War produced and imported materiel at a rate and scope barely imaginable a generation before. The following sums of firearms and edged weapons alone provide stark evidence to the phenomenon of mass production and its capacities:

Rifled muskets (3.5 million)

Appearing (and departing) early were 700,000 rifles from Austria, Prussia, France, Belgium and elsewhere, dumped on the voracious American market in the first two years of the war. Of better repute was the first general issue rifle in the U.S. Army, the Model 1841, often called the Mississippi Rifle after 1847 when it was issued to Colonel Jefferson Davis’ 1st Mississippi Infantry Regiment during the Mexican War. The Springfield, a.k.a. United States Rifle Musket Model 1861 or Model 1863, was the most widely made by far, with over 700,000 produced at its home armory in Massachusetts and another 900,000 created elsewhere to exacting standards. Second most common in the Union Army and first in the Confederacy was the slightly lighter English-made 1855 Model Enfield Rifle Musket, with 800,000 copies used in the war.[42]

Bayonets (1.5 million)

A soldier would beg, buy, or steal a good shoulder arm. A bayonet was a burden, except as a digging or cooking implement. Inducing fear in opponents more than incisions, they were almost as dangerous to comrades in close quarters. Despite extensive training, soldiers rarely jabbed as instructed. When within arm’s length of their opponents, combatants most often instinctively grabbed their muskets by the muzzle and swung them like clubs.[43]

Swords (700,000)

Muskets and cannon of the Civil War relegated a once deadly weapon to an ornamentation. Like its cousin the bayonet, it was more effective as an instrument to induce panic, which it did effectively on occasion when wielded by mass cavalry.[44]

Pistols (650,000)

Ranging from antique flintlocks to new revolvers, holding from one to nine shots, hundreds of variations saw use. The hefty Colt .44 caliber six-shooter became the official United States New Army Model 1860 Revolver, with over 100,000 ordered by the government. Thousands more were acquired by men and officers out of their own pocket. The lighter and shorter Colt .36 caliber Navy revolver had 200,000 made from its 1851 introduction to 1865 and was the chief design for nearly all 10,000 Confederate-made pistols. Union purchases also included 125,000 Remington .44’s, tens of thousands of Starr handguns, and dozens more makes and models.[45]

Smoothbore muskets (600,000)

These shoulder arms differed from their rifled counterparts in that smoothbores were older, cheaper, and far less accurate. However, some companies preferred them as they tended to be far less prone to jamming. At the time of Ft. Sumter, the U.S. Armed Forces possessed 300,000 usable smoothbore muskets. The young Confederacy acquired around 130,000 of these from raided federal government stores.[46]

Breech-loading Carbines (230,000)

The three most-common were the Sharp’s Carbine (over 90,000 use); Spencers (over 77,000); and the Burnside Carbine (approximately 55,000), with other producers contributing the balance. Initially used among cavalry, the device saw increasing use among infantry in the latter half of the war.[47]

Grenades (150,000)

The U.S. government ordered some 90,000 Ketchum grenades, conical devices with short finned tails, ranging from one to five pounds in weight. Less common was the “Excelsior,” with some 5,000 purchased by U.S War Department.[48]

Artillery (15,000)

Less than 5% of Civil War battlefield casualties came from artillery, and yet though in tiny proportion to all other firearms (0.3%), they did have disproportionate firepower.[49]

Concerning material innovation in weapons and other war materiel, enduring is the idea that, out of necessity, the South was more inventive than the North. Creative though it was in forging alternatives, such as the ironclad C.S.S. Virginia (a.k.a., Merrimack) and the famed submarine H.L. Hunley, the Confederacy never matched the Union’s eruption of innovation. In four years, the Confederate Patent Office granted 266 patents, whereas its Union counterpart granted over 16,000.[50]

Communications

Following is a case study in the informative effect of statistical analysis. Often tangentially addressed in Civil War discourse, communication systems were central to the functionality of mid-nineteenth century society. The Confederate breakdown in communications systems by 1864 was a major contributor to soldiers and civilians feeling isolated, supply networks becoming inefficient or failing altogether, and Union forces being able to apply an isolate-and-conquer approach to conclude the war.

The war itself occurred within a communications revolution. In 1776, 1 in 200 citizens had a newspaper subscription; in 1860, it was nearer 1 in 15 in the South and 1 in 6 among Northerners. From 1835 to the start of the Civil War, the number of newspapers in the country went from 800 to 2,500.[51] In 1800 less than 70% of adult white males could read and write. By the time artillery pounded Fort Sumter, the literacy rate among them neared 90%. In 1850, it took ten weeks to send information from St. Louis to San Francisco. In 1860, the Pony Express cut the time to ten days. By 1862, the telegraph accomplished the task in ten minutes.[52]

Concerning the magnetic telegraph, as it was known, the Union dominated this more than any other form of communication. The Confederacy employed some 1,500 telegraphers. The Union had over 12,000—a number larger than most Confederate armies. Both sides depended heavily on private corporations for hardware and operation, but the South had nothing that could rival the size or wealth of northern-based companies such as Western Union or American Telegraph. As the war dragged on, the Confederacy never exceeded 500 miles of wire in operation. In contrast, the Federals eventually laid down 15,000 miles of wire, enough to span the continent five times. With limited means and engineers, Confederate telegraphy was often intercepted and deciphered. Reportedly, no Union code was ever compromised during the entire war.[53]

So too the Union held sway in newsprint. Despite the iconic image of the Charleston Mercury announcing the dissolving of the Union, Robert Barnwell Rhett’s secessionist paper rarely had a circulation of more than 5,000 a week, whereas the New York Times routinely had over 100,000 readers a day. While sketch artists and woodcarvers for Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization had their images seen by 120,000 for each issue, the Confederacy had to outsource production of their official seal to craftsmen in Britain. The pro-Democrat Chicago Times was only seven years old at the war’s inception, but it already outsold and out-printed Richmond’s five papers combined.[54] The New York Herald boasted the nation’s largest following and employed some 60 correspondents, whereas the Memphis Appeal lost its base of operations in 1862, and spent the rest of the war printing sporadically from various points in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Most northern papers enjoyed an increase in subscribers during the war, while most of the South’s 800 dailies and weeklies had either ceased operation or drastically curtailed their pages by late 1863.[55]

Though generally more accurate than their Confederate counterparts in calculating troop strengths, Union papers were just as capable of guesswork. Harper’s Weekly claimed Major General John Pope lost Second Manassas because he had only a “handful of men.” Pope’s numbers were closer to 75,000.[56] When Robert E. Lee marched towards Gettysburg with no more than 80,000 men, the New York Times guessed he had an unthinkable 500,000.[57]

The Conflict as an International Phenomenon

The Civil War has been popularly viewed as a predominantly “American” event, but more recent scholarship increasingly interprets it in a more global context. At midcentury, the United States served as a prime example of the fluidity of international borders and populations. The recent annexation of the Republic of Texas, conquest and acquisition of nearly half of Mexico, filibuster expeditions into central and South American, missionary zeal through the Second Great Awakening, and the prying open of Japan dramatically expanded the sphere of U.S. influence. Additionally, the internationalization of the Industrial Revolution, an ongoing Taiping Rebellion in China (1850-1864), neo-colonialism, slave-smuggling operations through New York, New Orleans, etc., blurred boundaries and displaced populations. The exportation of moderate and radical socialism out of Europe after 1848 alone has led many historians to conclude that the Civil War was not only about blue and gray, black and white, but also red.[58]

Statistical analysis largely substantiates this international interpretation. Following are samples of such corroborating evidence:

Demographics

The push and pull of the globe’s commercial, political, ideological, and environmental dynamics heavily affected, among other things, U.S. demographics.

In 1860, 3.5% of those living in the Deep South were foreign-born, whereas the ratio in the north neared 20%. The pull of factory work in the Northeast, temperate farmland in the Midwest, plus mining and port towns in the West led 7 out of 8 immigrants onto free soil. Wartime influx was so high that immigration outpaced military losses, with more than 800,000 arriving between 1861 and 1865.These individuals constituted a large percentage of the Union’s labor edge. Notably, nearly a quarter soldiers in blue were foreign-born.[59]

Especially for first-generation newcomers, exclusion was the norm. The American Party or the Know-Nothings (a nativist party with xenophobic leanings) may have had nearly one million members by 1855. Discrimination was common within Federal ranks, not only along ethnic and racial lines, but also denominational. Out of 150,000 Jews in U.S., 7,000 served in blue and 3,000 in gray, and many encountered xenophobia. Around one in six Union soldiers were Catholic, in a nation where Protestants held a clear plurality. Nativists covertly and overtly lamented the growing Catholic presence, which some viewed on par with the secessionist threat, noting that there were more foreign-born Catholics in blue than there were Virginians in gray.[60]

In contrast, nearly every African American was born in the U.S., making them one of the largest cohorts among the U.S.-born. Among the free blacks, 132,000 lived in what would become the Confederate States, another 130,000 lived within the Border States, and 226,000 lived in the North.[61] There were some 20,000 Americans living in Canada by 1861, many of them African Americans.[62]

However, the foreign born did have a large presence in the South, primarily in urban centers. Around 13% or Richmond’s residents hailed elsewhere in the Americas or from oversees. In Savannah it was 20%, Memphis 30%, and New Orleans 38%.[63]

Commerce

More than a quarter of all British and French jobs were directly or indirectly tied to trade with the U.S., especially in textiles and grains. Likewise, many American farms, railroads, plantations, mills, and banks ran on international investment and consumer demand. Two intertwining domestic policies greatly affected these relationships—the Union blockade and the Confederate cotton embargo. The cotton embargo was never official policy and it became hypothetical once the blockade began.

Northern and Southern officials knew that independence in the American Revolution came largely through foreign intervention (indeed, by 1781, nearly half of combatants fighting against the British were French, and nearly 90% of Continental Army’s ammunition and artillery were of French manufacture.) Though their goals were in opposition, the Union’s blockade and the Confederacy’s embargo produced a similar outcome. By late 1862, the Union had over 400 ships and 28,000 men monitoring the Southern shores. In opposition, the Confederacy mustered just thirty armed vessels and a few thousand sailors.[64] As for blockade runners, only about 1-in-10 were caught in 1861. By 1865, the U.S. Navy caught half of all departures.[65]

With respect to the cotton embargo, the Confederate federal and state governments believed Britain absolutely depended the white fiber, as over 70% of its raw cotton came from the southern United States.[66] In 1860, the number one U.S. export was cotton. By 1862, cotton exports were at 2% of pre-war levels. Unfortunately for the secession strategy, the 1860 harvest was one of the most productive on record, and British warehouses were filled with surplus. Even as supplies dwindled, by 1863 new supplies came in to Britain from Egypt, India, Brazil, as well as several tons smuggled out of the South.[67] Historian Charles Hubbard makes a poignant observation concerning the cotton diplomacy saga—in the end, no one was more dependent on cotton than the Confederacy.[68]

If the blockade and embargo stifled Confederate trade, Confederate raiders had similar though smaller impact upon individual investors with the Union. By the end of June 1861, France, Britain, and Spain had declared neutrality in the Civil War, permitting the selling of arms and ships to belligerents under international law. Immediately, the Confederacy contracted British shipbuilders to construct seafaring commerce raiders. Though it was illegal under British law to sell armed ships to belligerents, entrepreneurs sidestepped the restriction by constructing unarmed cruisers and then equipped them with cannon in the Azores or the Bahamas. The Confederacy received some eighteen cruisers in this fashion.[69]

Designed to seek and destroy Union merchant vessels, three were conspicuously lethal. The CSS Florida captured or sank thirty-six commercial ships, the CSS Shenandoah another forty, and the CSS Alabama an astounding sixty-six. U.S. citizens lost millions of dollars in ships and cargo. Insurance rates and import prices doubled and tripled. Yet after the war, in a landmark case for international law, the Alabama Claims of 1872 awarded the U.S. government $15,500,000 in British gold for the commerce raiders’ extralegal activity.[70]

A Note on Economics

With its precipitous growth in size and scope, the conflict required enormous amounts of economic infusion and interference at the state and federal levels. I am disputing the frequent use of the term modern war, as it is so subjective, but I simply need to be more focused on the main point.

Rising costs forced the Lincoln administration to form the first national income tax in U.S. history (August 5, 1861). Richmond followed in 1862 with a 5% levy, increased in 1864 to 10%, plus a tax on production (tax-in-kind on 10% of food, livestock, and other materiel).[71]

As invasive as the income tax may have felt, civilians struggled more from inflation, which neared 100% for the Union and eventually reached 9,000% for the Confederacy.[72] The main culprit for both sides was the printing of paper notes, a technical illegality for both governments, as their Constitutions only permitted their legislatures to coin money. The U.S. Treasury eventually issued $450 million in paper currency not backed by gold or silver and essentially forced the population to accept the greenbacks “for all debts public and private.”[73]

Confederate money differed in that it guaranteed to be redeemable in silver two years after the successful conclusion of the war. As military defeats and Federal occupation increased, a desperate Confederate Treasury issued more notes, in excess of $1.5 billion by 1865, with counterfeiters adding millions more.[74]

As damaging as the monetary collapse was for the Confederacy, the cost of saving the Union proved colossal as well. By the end of the war, the US. public debt went from approximately $65 million in 1860 to $2.8 billion by 1866, or an increase of 4,308%, by far the worst percentage increase in American history.[75]

Statistics and Postwar Memorialization

Immediately after the war, few people expressed a desire to relive the event. This reticence changed gradually, as former soldiers began to gather in groups and reunions to process their memories, and sectional nationalists (especially regional political figures, southern white upper-class females, and children of veterans) began to glamorize the event and glorify their side. By the 1880s, the Civil War was undergoing a type of rebirth in the public sphere, and for veterans and civilians alike, statistics would play a central role in their respective narratives.

Monuments were initially rare until the 1880s, when aging combatants began to raise and requisition funds to erect memorials. Consistently, these were tributes at the unit level, usually for regiments and battalions. Stoic, solid, geometric, with minimal ornamentation, they almost invariable mentioned the number of officers and men who served in the detachment, including the total number killed, wounded, captured and missing during their tenure.

By the turn of the century, non-veterans became more active in memorialization, and moved in the direction of towering idolatry with emphases on patriotism and glorification of combat. Prime examples are the Pennsylvania State Monument (1913) and the Virginia State Monument (1917) at Gettysburg.

Concerning the question of why the North won, it was Unionists who avoided mentioning statistics, instead citing claims to the moral high ground and the abolition of slavery. Conversely, Confederate devotees, including those who erected monuments void of specifics, chose to reference statistics at length when explaining how and why the Confederacy lost. In many regards, statistics were a foundation of the Lost Cause mythos.

Representative of this approach, and its tendency towards imprecision, was Bennet Young’s speech at the 1913 Gettysburg Great Reunion. To a crowd of over 10,000 and scores of journalists, the commander in chief of the United Confederate Veterans proclaimed:

Of the 600,000 Southern soldiers, one in every eleven died on the battlefield under the Confederate flag. Of the 3,000,000 men who came, as they believed, to save the nation's life, 4.7 per cent, died under the Union flag. The issues that demanded these unparalleled sacrifices…We believe we failed, not because we were wrong, but because you men of the North had more soldiers, better food, longer and better guns, and more resources than the men of the South.[76]

Bennett was of course correct that Union forces outnumbered Confederate, although the ratio was closer to 2-to-1 rather than 5-to-1. Ironically, during the conflict itself, pro-Confederate newspapers (regardless of whether they supported the Richmond government) frequently overstated Confederate numbers in battles and underestimated Union effectives. They also often presented very conservative losses on their own side and greatly inflated Union casualties, due largely to limited information and a desire to appeal to readers. By the end of the century, for the same reasons of marginal information and reader appeal, southern nationalists inverted Confederate imbalances to the negative to portray “inevitable” defeat.

This image of overwhelming odds received a measure of validation near the centenary, partly through J.G. Randall and David H. Donald’s overview Civil War and Reconstruction (1969). Randall and Donald highlighted the imbalance of engineers, gunsmiths, and mechanics, the 10-to-1 Union advantage in ship construction, the 30-to-1 edge in firearms manufacturing, etc. As the authors noted however, this did not preclude any chance for the Confederacy to achieve independence. The relatively small size of the existing U.S. Army (17,000, of which more than a third resigned to join the Confederacy), the limited size of federal government, the enormity of the 11-state opposition (3,500 miles of coastline and 770,000 square miles of interior), plus other factors made a different outcome well within the scope of achievability. As many observed at the outset, the Continental Congress secession movement of 1776 used time, space, and interior lines to its advantage, and fought for eight years to attain independence.[77]

Regarding postwar depictions of all soldiers as dauntless and unflinching, Ella Lonn’s Desertion in the Civil War (1928) revealed that approximately 200,000 Union troops and 120,000 Confederates abandoned their posts during the war. Among multiple reasons, a primary one involved the citizen-soldier aspect, as more than 97% of all military personnel were not professional soldiers, and few envisioned in 1861 that the war would reach their own families let alone themselves. Studies on draft evasion indicate that some 250,000 individuals evaded their respective conscriptions, either by hiring substitutes, successfully gaining exemption for professional or personal reasons, or by simply failing to report.[78]

While current researchers have enormous (and growing) amounts of information about the war, and exemption from its consequences, individuals within the conflict were forced to work with few and often dubious sources. In their world, guesses, rumors, and fear were often indiscernible from accurate data. As a result, social scientists have much work before them in gathering and interpreting the arithmetic for a modern audience. There is also much work left to be done in better understanding how the war’s populations came by their numbers, and how those numbers altered their perceptions of reality.

- [1] Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 1:489.

- [2] Barton quoted in Michael C.C. Adams, Echoes of War: A Thousand Years of Military History in Popular Culture (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002), 23-24.

- [3] For burials in U.S. National Cemeteries, see: Quartermaster General’s Office, Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defense of the Union, 17 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865-1872); and Robert Poole, On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery (New York: Walker and Co., 2009); Estimate of Confederate burial locations from Richard Owen and James Owen, Generals at Rest: The Grave Sites of the 425 Official Confederate Generals (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1997), xxxiii.

- [4] Estimate of approximately 355,000 Union dead from Quartermaster General’s Office, Roll of Honor,16: viii.

- [5] William F. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (Albany, NY: Albany Publishing, 1889); Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-65 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1900); Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 6-7.

- [6] Margaret Humphreys, The Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 311. J. David Hacker, “A Census-based Count of the Civil War Dead,” in Civil War History 57, no.4 (December 2011): 328.

- [7] Charles Royster, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 147-50. See also: Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Vintage Books, 2008); Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- [8] Mark E. Neely, Jr., “Was the Civil War a Total War?” in Civil War History 50, no.,4 (December 2004): 434-58; Neely, Jr., The Civil War and the Limits of Destruction (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). See also: Jeremy Black, The Age of Total War: 1860-1945 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006).

- [9] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 856.

- [10] Nicholas Marshall, “The Great Exaggeration: Death and the Civil War,” in Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no.1 (March 2014):3-27.

- [11] Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 32-33; Faust, This Republic, 10, 180.

- [12] For statistics on unknown Union burials, see; Quartermaster General’s Office, Roll of Honor.

- [13] Estimates of equine casualty rates from Gene C. Armistead, Horses and Mules in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013), 7-8.

- [14] Nicholas Marshall, “The Great Exaggeration: Death and the Civil War,” in Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no.1 (March 2014):3-27.

- [15] KIA ratio for the Battle of Shiloh based on 90,000 estimated engaged and KIA figures from O. Edward Cunningham, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2009), 421-4. Chickamauga’s ratio is based on statistics from David J. Eicher, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001), 590, and Peter Cozzens, This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 534. Gettysburg KIA calculated from United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901) Ser. 1, vol. 27, pt. 1, pp. 187, 346. Locations of wounds and resulting fatality rates from Charles Beneulyn Johnson, Muskets and Medicine (Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Co., 1917), 131-2;George W. Adams, Doctors in Blue (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1952), 114. Number of dead in all cases are rounded estimates from: The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901); Livermore, Numbers and Losses; Frederick Phisterer, Record of the Armies of the United States (New York: Scribner’s and Sons, 1893); and Paul E. Steiner, Disease in the Civil War (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publishing, 1968).

- [16] Adams, Echoes of War, 17-20, 199-200, 225; Glenna R Schroeder-Lein, Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine (London: Routledge, 2015), 85-87.

- [17] Adams, Echoes of War, 135-6; Johnson, Muskets and Medicine, 131.

- [18] Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978), 253. The Official Records estimates the number of Union typhoid deaths to be nearer 27,000; Frank R. Freemon, Gangrene and Glory (Madison, WI: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1988), 206.

- [19] For life and death in Civil War prisons, see: William B. Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1930) and Lonnie R. Speer, Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997). Total KIA in above battles calculated from Livermore, 78-115; Edward H. Bonekemper III, A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius (Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 2004), 308-311; Alfred C. Young, III, Lee's Army during the Overland Campaign: A Numerical Study (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2013), 235-40; from these data sets, the lowest probable KIA total would be approximately 42,000 and highest probable total would approach 54,000, lower than the total estimated 57,300 of those who died in prison.

- [20] Estimate of average soldier age from Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 62. Estimated total worth of enslaved humans in 1860 from: Roscoe L. Ashley, The American Federal State: Its Historical Development, Government, and Policies (New York: Macmillan and Co., 1914), 167; and Kinshasha H. Conwill, ed., Dream A World Anew: The African American Experience and the Shaping of America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2016), 55.

- [21] Enslaved mortality from Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 138-9. and Steven Mintz, African American Voices: The Life Cycle of Slavery (St. James, NY: Brandywine Press, 1993), 11. For narratives from former slaves discussing their perspectives and experiences, consider: George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Co., 1972).

- [22] John B. Boles, Black Southerners, 1619-1869 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1984), 65-69.

- [23] Ibid., 101.

- [24] Mills Lane, ed., Neither More Nor Less than Men: Slavery in Georgia (Savannah, GA: Beehive Press, 1993), xxiii; McPherson, Battle Cry, 6-7, 39. See also Clarence L. Mohr, On the Threshold of Freedom: Masters and Slaves in Civil War Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986).

- [25] Charles S. Sydnor, Slavery in Mississippi (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Pub., 1965), 245.

- [26] James B. Sellers, Slavery in Alabama (Birmingham: University of Alabama Press, 1950), 42.

- [27] Randolph B. Campbell, The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 56, 252.

- [28] Literacy rates from John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 202-3. Work processes from Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), 30-34.

- [29] Randall M. Miller and John David Smith, eds., Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery (New York: Greenwood Press, 1998), 283, 715.

- [30] South Carolina ranked first in the country with the highest proportion of slave-owning families, with nearly half possessing one or more slaves. The state’s declaration of secession mentioned slavery no fewer than eighteen times, by far more than any other issue; James L. Abrahamson, The Men of Secession and the Civil War, 1859-1861 (Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 2000), 84-86; Randall M. Miller and John David Smith, Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), 699-701; William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 135-6; Miller, Dictionary, 699.

- [31] In two counties (Issaquena and Washington), almost nineteen of twenty humans were enslaved. Mississippi’s declaration of secession mentioned slavery seven times; Charles S. Sydnor, Slavery in Mississippi (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Pub., 1965), 245.

- [32] Georgia’s ordnance of secession referred to slavery a remarkable 35 times.

- [33] Louisiana ranked first in the number of owners with 100 or more slaves (547). Though producing most of the country’s sugar, Louisiana still dedicated the majority of its tilled acreage to cotton, which grew predominately in the northwest part of the state along the Red River basin; Joseph K, Menn, The Large Slaveholders of Louisiana – 1860 (New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Co., 1964), 2-9.

- [34] Julia Floyd Smith, Slavery and Plantation Growth in Antebellum Florida, 1821-1860 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1973), 10.

- [35] David S. Cecelski, The Waterman’s Story: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 105-6, 117.

- [36] By far the most populous of the Confederate states, Virginia also ranked first in total slave population in 1860 with 491,000. Virginia was also a hub of the domestic slave trade, where owners found they could make more money dealing rather than working slaves. In the thirty years before the war, more than a quarter million slaves were sold in the Old Dominion. By 1860, there were more free blacks in Virginia (58,042) than slave holders (52,128); Frederic Bancroft, Slave-Traders in the Old South (Baltimore, MD: J.H. Furst Co., 1931), 237, 384-6.

- [37] Randolph B. Campbell, The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 56, 252.

- [38] James J. Gigantino II, ed., Slavery and Secession in Arkansas: A Documentary History (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015), xv-xvii.

- [39] For a synopsis of the members of the Confederate Convention, see Charles R. Lee, Jr. The Confederate Constitutions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963), 153-8.

- [40] William C. Davis, “A Government of Our Own”: The Making of the Confederacy (New York: The Free Press, 1994), 224-9. Historian Emory M. Thomas makes the intriguing observation that the Articles of Confederation were not considered as a viable alternative: Emory M. Thomas, The Confederate Nation, 1861-1865 (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 63.

- [41] Estimates of escapees to Union positions during the war range from Leslie Schwalm’s conservative estimate of 320,00 to Ira Berlin et al’s perhaps optimistic number of 474,000. See Leslie A. Schwalm, “Between Slavery and Freedom: African American Women and Occupation in the Slave South,” in Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War, LeAnn Whites and Alecia P. Long, eds., (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), 138-9; Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, Slaves No More: Three Essays on Emancipation and the Civil War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 178; John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 259-260; McPherson, Battle Cry, 79-80; Genovese, 648-9.

- [42] Detailed descriptions of the Springfield and Enfield appear in Philip Katcher, The Civil War Source Book (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1995), 55-59, and in Jack Coggins, Arms and Equipment of the Civil War (Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1990), 31-32.

- [43] Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 52, 260; Coggins, Arms and Equipment, 29.

- [44] Katcher, Source Book, 60-61; Wiley, Life of Johnny Reb, 296-7.

- [45] Boatner, 167; William A. Albaugh III and Edward N. Simmons, Confederate Arms (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Pub., 1957), 9.

- [46] Gregory A. Coco, The Civil War Infantryman (Gettysburg: Thomas, 1996), 67.

- [47] Coggins, 58-59; Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank, 63; Robert V. Bruce, Lincoln and the Tools of War (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1956).

- [48] Coggins, 97-98.

- [49] Boatner, Dictionary, 168; Wiley, Life of Johnny Reb, 298.

- [50] Bruce Levine, Half Slave and Half Free: The Roots of the Civil War (New York: The Noonday Press, 1992), 68.

- [51] Brayton Harris, Blue & Gray in Black & White (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s Inc., 2000), 9.

- [52] Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, 2 parts (Washington D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, 1975),1:365. In 1850, while approximately 85% of the U.S. free population were literate, much of the rest of the world lagged far behind. In comparison, 67% in Britain and 25% in Eastern Europe were literate. See: McPherson, Battle Cry, 19-21; Harris, Blue & Gray, 11.

- [53] Boatner, Dictionary, 792; E.J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital: 1848-1875 (New York: New American Library, 1979), 59-61. On Lincoln and the War Department Telegraph Office, see: David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 392 and David H. Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1939).

- [54] William E. Huntzicker, The Popular Press, 1833-1865 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 142-3.

- [55] J. Cutler Andrews, The South Reports the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970), 513; Huntzicker, 132, 140; Donald E. Reynolds, Editors Make War: Southern Newspapers in the Secession Crisis (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1970), 3.

- [56] John Tebbel and Mary Ellen Zuckerman, The Magazine in America, 1741-1990 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 23. An account of Second Manassas is in: Harper’s Weekly, November 8, 1862.

- [57] Confederate troop count estimation quoted by Harris, Blue & Gray, 277.

- [58] For the interrelationships between Europe’s 1848 revolutions and the American Civil War, see Alison Clark Efford, German Immigrants, Race, and Citizenship in the Civil War Era (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013); Andre M. Fleche, The Revolution of 1861: The American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

- [59]E.B. Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, 1971), 707; J. Matthew Gallman, The North Fights the Civil War: The Home Front (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publishing, 1994), 23; Phillip S. Paludan, “A People’s Contest”: The Union and the Civil War, 1861-1865 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 377. See also Ella Lonn, Foreigners in the Union Army and Navy (New York: Greenwood Press, 1951).

- [60] Bruce, Half Slave, 200; Kevin J. Weddle, “Ethnic Discrimination in Minnesota Volunteer Regiments during the Civil War,” in Civil War History 35 (1989):240; Ella Lonn, Foreigners in the Union Army, 586-96; Gerald S. Henig and Eric Niderost, Civil War Firsts: The Legacies of America’s Bloodiest Conflict (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 2001), 60-61.

- [61] Gallman, The North Fights, 23.

- [62] Robin W. Winks, The Civil War Years: Canada and the United States (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1998), 7-8.

- [63] Lonn, Foreigners in the Confederacy (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Pub., 1965), 3, 481, 497-9.

- [64] Philip Van Doren Stern, When the Guns Roared: World Aspects of the American Civil War (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965), 180.

- [65] McPherson, Battle Cry, 380.

- [66] May 4-5. See also Gavin Wright, “Slavery and the Cotton Boom,” in Explorations in Economic History 12 (Oct. 1975).

- [67] Van Doren Stern, When the Guns Roared, 64; Charles M. Hubbard, The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 21. For a more detailed perspective on the relationship between the free labor Union and free labor Britain, see Philip S. Foner, British Labor and the American Civil War (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1981).

- [68] Hubbard, Burden, 27.

- [69] Van Doren Stern, When the Guns Roared, 143-9.

- [70] Robert E. May, ed., The Union, the Confederacy, and the Atlantic Rim (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1995), 11.

- [71] McPherson, Battle Cry, 438, 443-8.

- [72] Richard C. Burdekin and Farrokh K Langdana, “War Finance in the Southern Confederacy, 1861-1865,” in Explorations in Economic History 30 (1993):357; McPherson, Battle Cry, 447.

- [73] Gallman, The North Fights, 96.

- [74] Gallman, The North Fights, 98; James A. Rawley, The Politics of Union (Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden Press, 1974), 50.

- [75] U.S. debt statistics from Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2016 Historical Tables Budget of the United States Budget, see https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/383, accessed August 17, 2017, and U.S. Census Bureau of the U.S. Commerce Department, Statistical Abstract of the United States, see https://www.census.gov/library/publications/time-series/statistical_abstracts.html , accessed May 27, 2019.

- [76] Bennett Young quoted in Lewis E. Beitler, ed. And comp., Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, Report of the Pennsylvania Commission (Harrisburg, PA: Wm Stanley, State Printer, 1915), 108.

- [77] J.G. Randall and David H. Donald, The Civil War and Reconstruction (Lexington, KY: Heath, 1969), 8.

- [78] Ella Lonn, Desertion in the Civil War, 1998 reprint University of Nebraska Press (New York & London: The Century Co., 1928). See also: Joan E. Cashin, “Deserters, Civilians, and Draft Resistance in the North” in Joan E. Cashin, ed., The War was You and Me: Civilians in the American Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 165, 266; Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 32-33. On draft evasion, see Allan Nevins, The Organized War, 1862-1863 (New York: Scribner’s, 1959), 128-9; James Marten, Texas Divided: Loyalty and Dissent in the Lone Star State, 1856-1874 (Knoxville: University Press of Kentucky, 1990), 96; Cashin, “Deserters, Civilians”, 275.

If you can read only one book:

Arnold, James R. and Roberta Weiner, eds. American Civil War: The Essential Reference Guide. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011.

and

Wagner, Margaret E. et al, eds. The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002.

Books:

Armistead, Gene C. Horses and Mules in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 2013, 7-8.

Burdekin, Richard C. and Farrokh K. Langdanan. “War Finance in the Southern Confederacy, 1861-1865,” in Explorations in Economic History 30 (1993): 352-76.

Flagel, Thomas R. The History Buff’s Guide to the Civil War: The Best, the Worst, the Largest, and the Most Lethal Top Ten Rankings of the Civil War. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2010.

Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War. Albany, NY: Albany Publishing Company, 1889.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Hacker, J. David. “A Census-based Count of the Civil War Dead,” in Civil War History 57, no.4 (December 2011): 307-48.

Lee, Jr., Charles R. The Confederate Constitutions. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963, 153-8.

Livermore, Thomas L. Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-65. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900.

Lonn, Ella. Desertion During the Civil War. New York and London: The Century Company, 1928, chaps. 1, 2, 8, 10, and 17.

————. Foreigners in the Confederacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940.

Marshall, Nicholas. “The Great Exaggeration: Death and the Civil War,” in Journal of the Civil War Era 4, no.1 (March 2014): v.

Neely, Jr., Mark E. “Was the Civil War a Total War?,” in Civil War History 50, no.4 (December 2004): 434-58.

————. The Civil War and the Limits of Destruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Rowland, Leslie S., Joseph P. Reidy, Steven F. Miller, Barbara J. Fields, and Ira Berlin. Slaves No More: Three Essays on Emancipation and the Civil War. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960.

United States Army, Quartermaster General’s Office. Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defense of the Union. 27 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1869-1971.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975.

Wiley, Bell I. The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy. Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill company, 1943, chaps. 11 and 13.

————. The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union. Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill company, 1952, chaps. 6 and 12.

Wright, Gavin. “Slavery and the Cotton Boom,” in Explorations in Economic History 12 (Oct. 1975): 439-51.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

This is the National Park Service’s statistical overview of populations, agriculture, economics, etc. relating to the Civil War.

This is the American Battlefield Trust’s introductory, military-centric statistics on the Civil War.

Ohio State ehistory overview of medical and casualty figures from the Civil War.

Other Sources:

No other sources listed.