Johnny Reb

by Richard G. Williams, Jr.

Johnny Reb—in popular culture, as well as the serious study of the Civil War—is the symbolic representation of the ordinary Confederate soldier. The name appears to have originated from the practice of Yankees calling out “Hello Johnny” or “Hello Reb”. Johnny Reb has been celebrated in popular culture with songs like “I’m a Good Old Rebel” and “Johnny Reb” as well as in television shows such as The Rebel which ran from 1959-1961. These popular culture portrayals helped cement this perspective of the common Confederate soldier in the psyche of many Americans. It is the same perspective that is often reflected on the courthouse Confederate monuments that dot the Southern landscape to this day. Historian Bell Irvin Wiley brings some clarity to our understanding of Johnny Reb’s common traits: “The average Rebel private belonged to no special category. He was in most respects an ordinary person. He came from a middle-class rural society, made up largely of non-slaveholders, and he exemplified both the defects and the virtues of that background. He was lacking in polish, in perspective and in tolerance, but he was respectable, sturdy and independent. He was comparatively young, and more than likely unmarried…. His craving for diversion caused him to turn to gambling and he indulged himself now and then in a bit of swearing. But his tendency to give way to such irregularities was likely curbed by his deep-seated conventionality or by religious revivals.” “He had a streak of individuality and irresponsibility that made him a trial to officers during periods of inactivity. But on the battlefield, he rose to supreme heights of soldierhood. He was not immune to panic, nor even cowardice, but few if any soldiers have had more than he of élan, of determination, of perseverance, and of the sheer courage which it takes to stand in the face of withering fire. He was far from perfect, but his achievement against great odds in scores of desperate battles through four years of war is an irrefutable evidence of his powers and an eternal monument to his greatness as a fighting man.” When Johnny Reb returned from the war after the surrender at Appomattox, he often came home penniless and with little means to rebuild his life. Many rank and file veterans simply wanted—for themselves and their posterity—a return to some semblance of normalcy after Lee’s surrender. Johnny Reb was remembered and honored after their return for what they did after the war, as much as for what they did during the war. The awareness of the sacrifices of Johnny Reb became more prevalent as the old veterans began to die off. One might think that the type of sacrifice and loss that prompted such homage could sour the descendants of Johnny Reb toward any type of military service for several generations—especially service in the ranks of their conqueror. Ironically, the opposite is true. And that irony could be Johnny Reb’s most enduring legacy. Johnny Reb’s enduring legacy is evidenced by his descendant’s disproportionate service in all branches of the U.S. Military. A 2013 study showed that while representing only 36% of the country’s population, 44% of all recruits hail from the South (though while considering these statistics, it is also important to note that a significant number of these Southern recruits are black soldiers). Johnny Reb’s legacy endures.

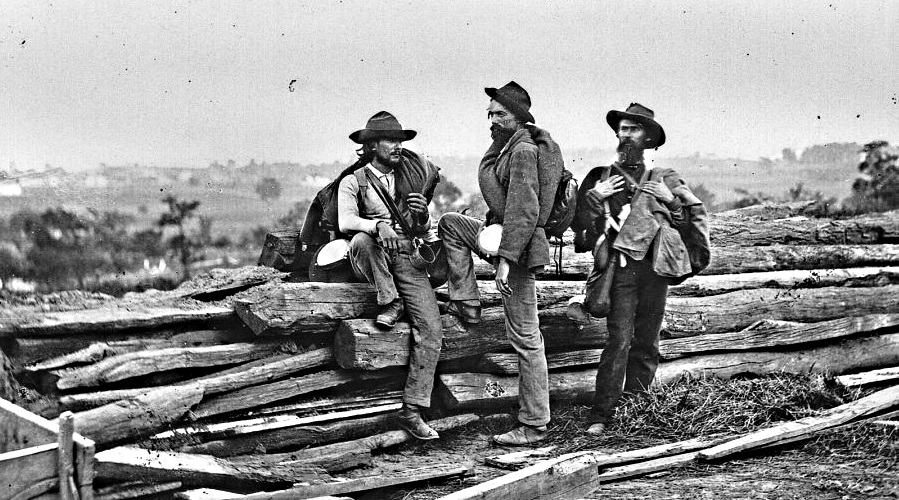

Three Confederate prisoners in July 1863 near Gettsyburg, PA.

Photograph Courtesy of: The Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, digital ID cwpb.01451

Whether vilified or revered, the moniker “Johnny Reb” is forever etched into the American lexicon. Johnny Reb—in popular culture, as well as the serious study of the Civil War—is the symbolic representation of the ordinary Confederate soldier.

Historian Bell Irvin Wiley, who wrote the definitive work on the common Confederate soldier, explains the likely origination of the term, Johnny Reb:

The common soldier of the Confederacy has for a long time borne the title of Johnny Reb. The name seems to have originated from the practice of Yankees who called out, “Hello Johnny” or “Howdy Reb” to opponents across the picket line. Gray-clads liked the sobriquet, and accustomed as they were to appropriation of Federal food, clothing and guns, they saw no reason to spurn a catchy name because it was used by their opponents. So they adopted the term in both its separate and combined forms. Descendants might be irked by the connotation of rebellion, but not the original Johnny. He not only considered himself a rebel but he gloried in the name.[1]

Glorying in being labeled a “rebel” was expressed in a song penned by Confederate Major Innes Randolph which begins:

Oh, I'm a good old Rebel,

Now that's just what I am.

For this "Fair Land of Freedom"

I do not give a damn!

I'm glad I fit against it,

I only wish we'd won,

And I don't want no pardon

For anything I done. [2]

Johnny Reb has also been celebrated in more contemporary times in song by country music singer Johnny Horton (April 30, 1925 – November 5, 1960). Horton released the hit single (written by Merle Kilgore) on the eve of the Civil War Centennial in 1958. The lyrics give great insight to the revered aspect of the legendary character of Johnny Reb, as well as giving a nod to the reconciliation view of the Civil War which was popular at the time:

You fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

Saw you a marchin' with Robert E Lee

You held your head high tryin' to win the victory

You fought for your folks but you didn't die in vain

Even though you lost they speak highly of your name

Cause you fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

I heard your teeth chatter from the cold outside

Saw the bullets open up the wounds in your side

I saw the young boys as they began to fall

You had tears in your eyes cause you couldn't help at all

But you fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

I saw General Lee raise a sabre in his hand

Heard the cannons roar as you made your last stand

You marched into battle with the Grey and the Red

When the cannon smoke cleared it took days to count the dead

Cause you fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

When Honest Abe heard the news about your fall

The folks thought he'd call a great victory ball

But he asked the band to play the song Dixie

For you Johnny Reb and all that you believed

Cause you fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

(Yeah) You fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb

You fought all the way Johnny Reb Johnny Reb

(Yeah) You fought all the way Johnny Reb [3]

The symbolic Johnny Reb was also popularized and depicted in the successful ABC television series, The Rebel which ran from 1959 to 1961. The time frame of the series also coincided with the opening commemoration of the Civil War Centennial. This timing no doubt contributed to the show’s success which, at its peak, claimed a 35 per cent share in its Sunday evening time slot. The show starred actor Nick Adams as Johnny Yuma. Wikipedia gives an accurate synopsis of the series:

The series portrays the adventures of young Confederate Army veteran Johnny Yuma, an aspiring writer, played by Nick Adams. Haunted by his memories of the American Civil War, Yuma, in search of inner peace, roams the American West, specifically the Texas Hill Country and the South Texas Plains. He keeps a journal of his adventures and fights injustice where he finds it with a revolver and his dead father's sawed-off double-barreled shotgun. [4]

What’s important to note, for the purposes of this essay, is that both Horton’s song and Adams’s portrayal, emphasize both the ordinary aspect of Johnny Reb, as well as the common Confederate soldier’s heroic and honorable character. Thus, these popular culture portrayals helped cement this perspective of the common Confederate soldier in the psyche of many Americans. It is the same perspective that is often reflected on the courthouse Confederate monuments that dot the Southern landscape to this day. Rather than being inscribed with lofty and wordy expression, the text for these monuments are more often than not very simple; such as the one inscribed on the monument at the Bath County Virginia courthouse in Warm Springs, Virginia. It reads, simply:

CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS

1861-1865

“LEST WE FORGET”

Of course, it would be correct to state that viewing Johnny Reb solely through the lens of 1960’s pop-culture depictions or through the text offered on courthouse monuments offers an over-simplification of what manner of men these soldiers were. Nonetheless, it is this perspective that still, to a large degree, holds sway in the view of many. And while it may be an over-simplification, it is not without merit. Historian Bell Irvin Wiley again brings some clarity to our understanding of Johnny Reb’s common traits:

The average Rebel private belonged to no special category. He was in most respects an ordinary person. He came from a middle-class rural society, made up largely of non-slaveholders, and he exemplified both the defects and the virtues of that background. He was lacking in polish, in perspective and in tolerance, but he was respectable, sturdy and independent.

He was comparatively young, and more than likely unmarried… . His craving for diversion caused him to turn to gambling and he indulged himself now and then in a bit of swearing. But his tendency to give way to such irregularities was likely curbed by his deep-seated conventionality or by religious revivals.[5]

Despite the ordinary aspect of Johnny Reb’s character, Wiley also makes it clear that his reputation for honor and courage on the battlefield is one which was well-earned:

He had a streak of individuality and irresponsibility that made him a trial to officers during periods of inactivity. But on the battlefield he rose to supreme heights of soldierhood. He was not immune to panic, nor even cowardice, but few if any soldiers have had more than he of élan, of determination, of perseverance, and of the sheer courage which it takes to stand in the face of withering fire.

He was far from perfect, but his achievement against great odds in scores of desperate battles through four years of war is an irrefutable evidence of his powers and an eternal monument to his greatness as a fighting man.[6]

When Johnny Reb returned from the war after the surrender at Appomattox, he often came home penniless and with little means to rebuild his life. Yet the character that enabled his “achievement against great odds in desperate battles” would now rise to the occasion of a different battle, rebuilding the decimated South.

Johnny Reb was tired of body lice, tired of being hungry and constantly having to forage for food, tired of unsanitary camp life, tired of being outgunned and outnumbered, tired of being barefoot and threadbare, tired of being cold, tired of hardtack and hard marches, tired of missing loved ones and tired of bloodshed. Though many showed a willingness to fight on, even at Appomattox, they were simply tired of every aspect of war. Their dire straits were even shared by their horses with one Confederate soldier noting in early 1865 that his horse “looked more like a fence rail with legs than a horse.”[7]

Johnny Reb’s return home, though welcome, came with a new set of burdens:

Southern veterans returned singly or in pairs; they straggled into all parts of the South… the silence of exhaustion that better harmonized with their own despair. Few who underwent this experience ever erased the memory of the inglorious humiliation it engraved upon their hearts.

The Southern veteran came back to no such scene of jubilation as brightened the return of his adversary. Wearied in body, exhausted in spirit, he passed through wasted countrysides until he found retreat in a home that had been saddened by loss and impoverished by sacrifice. His was a retreat of a wounded stag seeking nothing better than the peace of solitude where the hounds of his enemy could not follow and the taunting cries of the victorious chase could not penetrate. [8]

Many rank and file veterans simply wanted—for themselves and their posterity—a return to some semblance of normalcy after Lee’s surrender. They wanted the death and destruction to cease. They wanted once again to till their land, sleep under their own roofs, support their families, educate their sons and daughters and worship their God. They wanted to rebuild, reconcile and reunite. And they did. Although that process was halting and imperfect and lacking—especially for those new citizens who were no longer slaves—white southerners remembered and honored Johnny Reb after his return for what he did after the war, as much as for what he did during the war. Obviously, not all that the returning Confederate veterans accomplished was noble. The systematic denying of civil rights of former slaves by the white ruling class in the decades that followed the war is a legacy that our nation struggles with to this day.

On June 3, 1990, former Marine Corps officer, Secretary of the Navy and Virginia Senator James Webb gave a speech at the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Webb is, himself, the descendant of several Johnny Rebs and this connection, along with his military background, gives Webb special insight into the legacy of Johnny Reb and why the common Confederate soldier is still, to some degree, remembered and honored by many Americans. Webb uses one regiment to illustrate the sacrifices offered by this common soldier:

We often are inclined to speak in grand terms of the human cost of war, but seldom do we take the time to view it in an understandable microcosm. Today I would like to offer one: The “Davis Rifles” of the 37th Regiment, Virginia infantry, who served under Stonewall Jackson. One of my ancestors, William John Jewell, served in this regiment, which was drawn from Scott, Lee, Russell and Washington counties in the southwest corner of the state. The mountaineers were not slaveholders. Many of them were not even property owners. Few of them had a desire to leave the Union. But when Virginia seceded, the mountaineers followed Robert E. Lee into the Confederate Army.

1,490 men volunteered to join the 37th regiment. By the end of the war, 39 were left. Company D, which was drawn from Scott County, began with 112 men. The records of eight of these cannot be found. Five others deserted over the years, taking the oath of allegiance to the Union. Two were transferred to other units. Of the 97 remaining men, 29 were killed, 48 were wounded, 11 were discharged due to disease, and 31 were captured by the enemy on the battlefield, becoming prisoners of war. If you add those numbers up they come to more than 97, because many of those taken prisoner were already wounded, and a few were wounded more than once, including William Jewell, who was wounded at Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862, wounded again at Sharpsburg (Antietam) on September 17, 1862, and finally killed in action at Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863.

The end result of all this was that, of the 39 men who stood in the ranks of the 37th Regiment when General Lee surrendered at Appomattox, none belonged to Company D, which had no soldiers left. [9]

The war had been fought primarily on Southern soil. Johnny Reb’s land had been decimated and its economy was in shambles. Theses soldiers were also in shambles—emotionally as well as physically. In 1866, the state of Mississippi spent a fifth of its budget on artificial arms and legs. The South had enlisted one-sixth of its white population; a significantly larger percentage than the North. The results were severe: The Confederacy suffered an estimated 12 percent of their soldiers killed verses 5 percent in the Union.

The awareness of the sacrifices of Johnny Reb became more prevalent as the old veterans began to die off. Former editor-in-chief of VFW magazine, Richard K. Kolb, explained this awareness in an article:

The Confederate dead did become important cultural heroes, who were perhaps more important to the South than departed heroes in many other societies, and who could be invoked to sanction values and behavior," wrote Gaines M. Foster in Ghosts of the Confederacy.

In the Deep South, Memorial Day was commemorated April 26, the day of Johnston's surrender. In the Carolina's, May 10, the day of Jackson's death, was chosen.

During the 1900s, reconciliation allowed for joint remembrances. The first Confederate Memorial Day service was held in the Confederate Section of Arlington National Cemetery in 1903. Three years later, Congress passed a law to care for Confederate graves in the North.

Monuments also played an essential cultural role in post-war Southern society. "For the veteran, the homage paid to the stone soldier symbolized his community's respect for him," Foster found. "It also signified the South's conviction that it had acted rightly."

Testimony to that conviction was found in the 544 monuments that sprouted in Southern soil from 1865-1912. More than half were erected after 1900. Initially dedicated in cemeteries, they soon graced courthouse lawns and city streets where prominence in the public eye was assured.

Unveilings were a social activity of the first order. When the Richmond Soldiers and Sailors Monument was dedicated in 1894, 10,000 vets marched by 100,000 spectators. Things came full circle when a monument to Confederate dead was unveiled in Arlington in 1914.[10]

One might think that the type of sacrifice and loss that prompted such homage could sour the descendants of Johnny Reb toward any type of military service for several generations—especially service in the ranks of their conqueror. Ironically, the opposite is true. And that irony could be Johnny Reb’s most enduring legacy.

Former Citadel Professor Ron Andrew Jr. explores this irony in his book about Southern military schools, Long Gray Lines:

Perhaps the most central and enduring element of the Lost Cause was the firm connection in the minds of southerners between martial virtues (courage, patriotism, selflessness, and loyalty) and moral rectitude. The image of the valorous soldier as a patriot and model citizen had antebellum roots, but it shaped and drew strength from the legend of the Lost Cause after the Civil War…. The Lost Cause [often personified in Johnny Reb] strengthened the southern military tradition. White southerners in the postbellum period, particularly as a result of the Confederate past and the powerful appeal of the Lost Cause, were apt to equate military service and martial valor with broader cultural notions of honor, patriotism, civic duty, and virtue. [11]

These “cultural notions of honor, patriotism, civic duty, and virtue” prompted, in large measure, by Johnny Reb’s sacrifice would begin manifesting themselves in real terms with the advent of the Spanish-American war. As Professor Andrew notes:

More emphatically than at any time since Appomattox, southerners reasserted their loyalty to the larger American nation, though without renouncing their Confederate past…. The war gave youthful cadets a chance to honor the sacrifices of their Confederate fathers and simultaneously declare their loyalty as Americans.[12]

One of the best examples of this new loyalty was expressed in a speech delivered on June the 14th, 1904 at the United Confederate Veterans reunion in Nashville, Tennessee. The oration was delivered by the Reverend Randolph McKim. Enlisting in the Confederate Army as a private shortly after graduating from the University of Virginia in 1861, McKim would eventually rise to the rank of first lieutenant and serve as chaplain of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry during the Civil War. Beginning in 1888, he served thirty-two years as rector of the historic Church of the Epiphany in Washington D.C. until his death in 1920.

Though McKim looked out upon a sea of aging, gray and bent Johnny Rebs this day, his mind was not only on them—it was on their sons and grandsons. McKim was looking into the face of the past, but his mind was clearly focused on the future. His words were prophetic:

We are loyal to the starry banner. We remember that it was baptized with Southern blood when our forefathers first unfurled it in the breeze. We remember that it was a Southern poet, Francis Scott Key, who immortalized it in the “Star Spangled Banner.” We remember that it was the genius of a Southern soldier and statesman, George Washington, that finally established it in triumph. Southern blood again flowed in its defense in the Spanish war, and should occasion require, we pledge our lives and our sacred honor to defend it against foreign aggression, as bravely as will the descendants of the Puritans… when the united republic, in years to come, shall call, “To arms!” our children, and our children’s children, will rally to the call, and, emulating the fidelity and the supreme devotion of the soldiers of the Confederacy, will gird the Stars and Stripes with an impenetrable rampart of steel. [13]

The effects of Johnny Reb’s legacy in regard to service in the United States military grew and continued through WWI, WWII, the Korean conflict, Vietnam and to the present day. Though not necessarily a conscious impact in the mind of 21st century military recruits; Johnny Reb’s enduring legacy is evidenced by his descendant’s disproportionate service in all branches of the U.S. Military. A 2013 study showed that while representing only 36% of the country’s population, 44% of all recruits hail from the South.[14]

While there are several factors accounting for these numbers, it can be easily argued that much of the disparity can be attributed to the South’s military tradition and Johnny Reb’s influence on that tradition.

Johnny Reb’s legacy endures.

- [1] Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978), 13.

- [2] James Innes Randolph, “I’m a Good Old Rebel”.

- [3] Merle Kilgore, “Johnny Reb”, 1959 SONY BMG Music Entertainment.

- [4] The Rebel (TV series) in Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rebel_(TV_series), accessed November 19, 2019.

- [5] Wiley, Life of Johnny Reb, 347.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Baker Isaac Norval, Civil War Memoirs, 18th Virginia Cavalry, Company F. Imboden’s Brigade (Lexington: Virginia Military Institute Archives), n.d., at http://digitalcollections.vmi.edu/digital/collection/p15821coll11/id/1471, accessed November 19, 2018.

- [8] Paul H. Buck, The Road to Reunion (New York: Random House, 1937), 32.

- [9] James Webb, “Remarks at the Confederate Memorial”, http://www.jameswebb.com/speeches-by-jim/remarks-at-the-confederate-memorial , accessed November 19, 2018.

- [10] Richard K. Kolb, “Thin Gray Line: Confederate Veterans in the New South,” in VFW Magazine 46, no. 6 (June 1997)

- [11] Andrew, Rod Jr., Long Gray Lines. (Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 47.

- [12] Ibid., 105, 106-7.

- [13] Randolph H. McKim, A Soldier's Recollections: Leaves from the Diary of a Young Confederate: With an Oration on the Motives and Aims of the Soldiers of the South (New York, Longmans, Green, and Co, 1910), 288-90.

- [14] Jeremy Bender, Andy Kiersz and Armin Rosen, “Some States Have Much Higher Enlistment Rates Than Others” in Business Insider at http://www.businessinsider.com/us-military-is-not-representative-of-country-2014-7 , accessed November 19, 2018. While considering these statistics, it is also important to note that a significant number of these Southern recruits are black soldiers.

If you can read only one book:

Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Books:

(A word of caution: There are many personal reminiscences by Confederate veterans and Confederate regimental histories written by veterans after the war, and they vary in quality and accuracy. Included in this bibliography are a selection but by no means an exhaustive list of these books, selected from among those recommended by Bell Wiley in The Life of Johnny Reb.)

Berkeley, Henry Robinson and William H. Runge, eds. Four Years in the Confederate Artillery: The Diary of Private henry Robinson Berkeley. Chapel Hill: Virginia Historical Society/University of North Carolina Press, 1961.

Brown, Maud Morrow. The University Greys: Company A, Eleventh Mississippi Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie, 1940.

Caldwell, J. F. J. History of a Brigade of South Carolinians, Known First as Gregg’s, and Subsequently as McGowan’s Brigade. Philadelphia, PA: King & Baird, Printers, 1866.

Casler, J. O. Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade. Guthrie, OK: State Capital Printers Company, 1893.

Dinkins, James. Personal Recollections and Experiences in the Confederate Army. By an Old Johnnie Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clark Company, 1897.

Farrar, J. R. Johnny Reb, The Confederate: A Lecture. Richmond, VA: W. A. R. Nye, Book and Job Printer, 1869.

Fletcher, W.A. Rebel Private Front and Rear. Beaumont, TX: Press of the Greer Print,1908.

Ford, A. P. Life in the Confederate Army Being Personal Experiences of a Private Soldier in the Confederate Army. New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1905.

Gilmor, Harry. Four Years in the Saddle. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1866.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008.

————. Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Hunton, Eppa. Autobiography of Eppa Hunton. Richmond, VA: The William Byrd Press, 1933.

Marten, James. Sing Not War: The Lives of Union and Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

McCarthy, Carlton. Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia. Richmond, VA: Carlton McCarthy and Company, 1882.

McKim, Randolph H. A Soldier's Recollections: Leaves From the Diary of a Young Confederate, With an Oration on the Motives and Aims of the Soldiers of the South. Longmans, Green, and Co., New York, 1910.

McMorries, Edward Young. History of the First Alabama Volunteer Infantry, C.S.A. Montgomery, AL: The Brown Printing Company, 1904.

McPherson, James M. What They Fought For, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

————. For Cause & Comrades. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Mitchell, Reid. Civil War Soldiers. New York: Viking Penguin, 1988.

Mixson, Frank. Reminiscences of a Private. Columbia, SC: The State Company, 1910.

Moore, Edwin A. The Story of a Cannoneer under Stonewall Jackson. New York and Washington: The Neale Publishing Company,1907.

Noe, Kenneth W. Reluctant Rebels: The Confederates Who Joined the Army after 1861. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Power, J. Tracy. Lee’s Miserables: Life in the Army of Northern Virginia from the Wilderness to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Robertson, Jr., James I. Soldiers Blue and Gray. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

Rosenburg, R. B. Living Monuments: Confederate Soldiers’ Homes in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Shaver, Lewellyn. History of the Sixtieth Alabama Regiment: Gracie’s Alabama Brigade. Montgomery AL: Barrett & Brown, 1867.

Smith, Daniel P. Company K, First Alabama Regiment or Three Years in The Confederate Service. Prattsville, AL: Published by the Survivors, 1885.

Toney, Marcus B. The Privations of a Private. The Campaigns under Gen. R.E. Lee; the Campaign under Gen. Stonewall Jackson; Bragg's Invasion of Kentucky; the Chickamauga Campaign; the Wilderness Campaign; Prison Life in the North; the Privations of a Citizen; the Ku-Klux Klan; a United Citizenship. Nashville, TN: Printed for the Author, 1907.

Watkins, Sam R. “Co Aytch,” Maury Grays, First Tennesee Regiment, or a Side Show of the Big Show. Chattanooga, TN: Times Printing Company, 1900.

Wert, Jeffrey D. A Brotherhood of Valor: The Common Soldiers of the Stonewall Brigade, C.S.A., and the Iron Brigade, U.S.A. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999.

Williams, David. Johnny Reb’s War: Battlefield and Home Front. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2000.

Wyeth, John Allen. With Sabre and Scalpel; The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1914.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

The National Park Service Civil War Series: The Civil War’s Common Soldier

Other Sources:

The Rebel: The Complete TV Series, 1959-1961.

This TV show is available on DVD, 2015 by Shout Factory Studio.