Regimental Histories

by Timothy J. Orr

Regimental histories were—and still are—a popular subgenre of Civil War history. They catalog a regiment’s campaigns by describing its organization, personnel, training, battle action, and casualties. Although each author’s style differs, regimental histories usually follow a lengthy, sentimentalist narrative. Not every regiment created its own history, but thousands did so, and together, they forged the first major attempt by veterans to control the commemoration of the war. Confederate historians, especially, did their best to reshape the memory of the war, adding to the Confederate myth known as the "Lost Cause." Although the last confirmed Civil War veteran died in 1956, unit histories continued to be published in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. By that point, they belonged to the realm of professional historians, and they remain so to this day. Modern regimental histories are more analytical than their nineteenth century counterparts and attempt to incorporate social history into their narratives. Currently, the publication of Civil War regimental histories shows no sign of stopping. Overall, regimental histories are troublesome sources, but they cannot be avoided by dedicated students of the war. They constituted some of the first histories of the war, and arguably the most important. If war is—at its simplest—the terrible tragedy of killing and dying, it is necessary to discuss the day-to-day lives of the men who killed and died between 1861 and 1865.

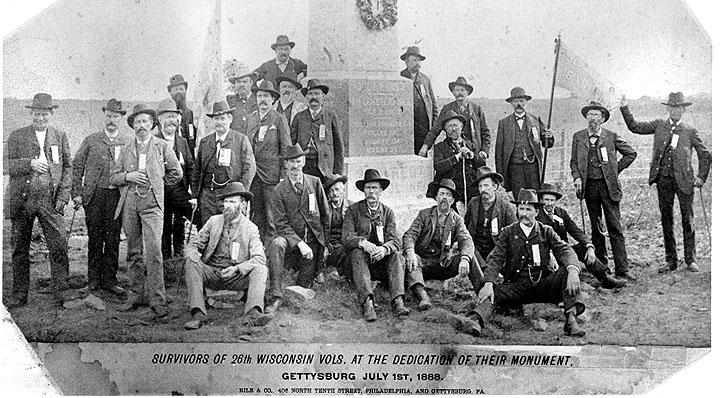

Survivors of the 26th Wisconsin Volunteers at the Dedication of Their Monument. Gettysburg July 1st, 1888.

Provenance Unknown

Regimental histories were—and still are—a popular subgenre of Civil War history. They catalog a regiment’s campaigns by describing its organization, personnel, training, battle action, and casualties. Although each author’s style differs, regimental histories usually follow a lengthy, sentimentalist narrative. Not every regiment created its own history, but thousands did so, and together, they forged the first major attempt by veterans to control the commemoration of the war. In this way, the Civil War presented a corrective to the popular notion that veterans resisted or only reluctantly remembered the violence in which they participated. Unlike veterans from other American wars, Civil War veterans rarely clammed up; they shared their war stories without shame or fear. Firmly believing that the curiosities of a soldier’s life were worth saving for posterity’s sake, veterans told their story without reservation. For instance, the regimental historian for the 12th New Hampshire wrote proudly in 1897, “Believing . . . that merit and not rank or riches deserve our praise, and that he who fought with the musket was just as good as he who commanded with the sword, it was decided at the outset that in this history, at least, if no where else, they [the officer and the common soldier] should in every respect, so far as possible, stand upon the same level.”[1]

Although veterans from both sides wrote regimental histories, Union veterans dominated the bookshelves early and often. Returning Union soldiers compiled their regiments’ official papers and handed them to accomplished authors, typically men who had served in their regiment from its official muster-in to its final muster-out. Veteran-authors sifted through hundreds of pages of official correspondence, interweaving the play-by-play of Civil War military campaigns with the various untold tales, personal letters, diary entries, and anecdotes told by the survivors.

It is not certain which Civil War regiment was the first to craft its own history, but none appeared before the year 1863.[2] Beyond any doubt, the earliest regimental histories came from Union veterans whose regiments mustered out before the war drew to a close. In their prefaces, these regimental historians professed to write solely for the benefit of their comrades and their families. For instance, Chaplain Richard Eddy—the primary author of the History of the Sixtieth Regiment, New York State Volunteers—left army service on February 20, 1863. When he returned to Albany, he compiled information with the assistance of two other officers. Within a few months, Eddy had completed a twenty-chapter, 360-page narrative. In his preface, he confirmed that the 60th New York’s regimental history was not written for public consumption, nor did he intend it to stand up to academic scrutiny. Instead, he had been motivated “chiefly from a desire to gratify the families and friends of those connected with the 60th Regiment, by placing before them a true account of the various vicissitudes through which that command has passed.”[3] Other wartime regimental historians had similar goals in mind. In his preface, the author of the 215-page history of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry, which appeared in 1864, Adjutant William P. Lloyd, argued that his sketch would not “elicit any interest from the public at large,” but if it met the approval of the veterans, “it will be answering my fullest expectations.”[4]

In general, the earliest regimental histories—and there were sixty-eight published between 1863 and 1866—presented the war as the soldiers saw it. Their memories were still raw, fresh, and unaltered by the passage of time. Early on, it was not beneath regimental historians to castigate their leaders, blaming them for the various disasters that cost men’s lives or needlessly prolonged the war. For instance, in his history of the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry, Evan Morrison Woodward lambasted Major General David Birney for failing to support the Pennsylvania Reserve Division at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Even going so far as to quote Birney’s testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, showing how it was in variance with the facts, Woodward wrote, “Birney [claimed he was] ordered to stop the fugitive ‘Pennsylvania Reserves’ from running!!! No one was ever ordered to do that, for no troops ever went in after them!”[5]

This shameless belittling of Union generals, while common in the 1860s, gradually disappeared from regimental histories as time passed. Simultaneously, more and more regimental histories appeared in print. The bulk of veteran-authored regimental histories were published between the twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth anniversaries of the war. The unexpected popularity of Ulysses Grant’s and William T. Sherman’s memoirs, Alexander McClure’s Annals of the War, and Century Magazine’s “Battles and Leaders” series prompted an explosion of Civil War literature in the publishing industry. [6] By 1880, wrote historian David W. Blight, American culture began welcoming stories written by soldiers.[7] The explosion of regimental histories during these years was enormous. In 1993, historians Robert Lester and Blair Hydrick cataloged all known regimental histories and personal narratives written by veterans between the end of the war and the opening decades of the twentieth century, concluding that the total number of regimental histories reached into the thousands. Just one small state—Connecticut—had produced 154 books. New York, the largest, produced 834.[8]

Most regimental histories followed the same scheme. Typically, they commenced with a chapter that described the regiment’s enlistment and organization, followed by chapters that narrated the regiment’s campaigns. Most often, the last chapter described the regiment’s muster-out, and then appendices contained biographical sketches of the officers, a complete roster (if one could be compiled), followed by short descriptions of the veterans’ reunions, if any had occurred.

Union regimental histories started off by describing Lincoln’s April 15, 1861, call for 75,000 militiamen, or barring that, whichever specific call had led to the creation of the unit in question. In the post-Reconstruction period, authors scrupulously avoided discussing the messy history of the war’s causes; however, if they attempted to provide the readership with a short description of the war’s political causes, they invariably did so from a sectional standpoint. Predictably, Union writers blamed the war’s arrival on irrational decisions made by southern slave owners, who emerged as the primary villains in their narratives. For instance, William Rauch, author of the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles’ history, believed the Confederate rebellion was inevitable. To him, the thoughts and ideas of the North and the South “were at [such] variance” in matters related to slavery that “sooner or later, the aspirations of one must to a greater or lesser extent become the guiding influence of the other.” So long as the United States lived half-slave, half-free, he wrote, war was the only result.[9] Another historian, John Day Smith, author of the 19th Maine’s history, began his book, “Some wars are justifiable; most are not. The War of the Rebellion—now generally called the Civil War—was a conflict that could not have been avoided by the North, except by giving up the old Union.” Making it clear that the fault lay entirely with the South, Smith concluded, “Revolution or rebellion is justifiable only when the existing government becomes oppressive and intolerable or when the rights of people are disregarded. Surely there was no ground for rebellion on the part of the Slave States.”[10]

Beyond delineating the causes of the war, Union regimental historians painted their nation’s cause as an unimpeachably glorious one. Failing to remember the swirl of contentious political opinions that divided the North in the spring of 1861, Charles A. Stevens, the author of the history of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, cast the scene as a period of unity and excitement. “It was a momentous era in American history—the life-struggle of the nation,” he wrote. “Everybody realized the danger, every one saw the necessity of promptly meeting it…So earnest had the people become, now that war was inevitable to save the Union, and to put down forever this scheme of secession, that more than double the number asked for [by the War Department] had enlisted and been accepted.”[11] The author of the 155th Pennsylvania’s regimental history spoke of the Union’s cause in similarly jubilant terms. He referred to the creation of his regiment as the “loyal uprising in western Pennsylvania.” Writing in 1910, he claimed that the Civil War generation possessed patriotism eminently superior to the current one. Fellow Pennsylvanians from the war years who gave blood and treasure to the cause, he wrote, “rose above partizanship in their zeal for the Union cause, disdained personal benefit or profit arising from the necessities of the Government, in vivid contrast with the prevailing commercialism of the present times.”[12]

The authors’ decision to paint a rosy picture of the Union’s war often complimented their purposeful omission of unpleasant tales from the war. As time passed, regimental historians became more likely to diminish or purposely forget the unsightly aspects of a Civil War soldier’s day-to-day existence. They rarely described drinking, gambling, prostitution, cowardice, desertion, courts-martial, military executions, or plundering—acts that abounded among the blue and gray during the wartime years. Egregiously, regimental historians purposely ignored the disagreements that marred the junior officer corps, problems that plagued nearly every regiment put into service. Even though personal feuds, political intrigues, and petty squabbles filled tens of thousands of official pages in the records of the adjutants-general, the historians erased that discord from public memory. For instance, during the war, the 118th Pennsylvania’s officer corps had been paralyzed by a bitter feud between Lieutenant Colonel James Gwyn and Captain Francis Donaldson, a dispute that ended only when Donaldson was court-martialed and dismissed from the service (for drawing his pistol on Gwyn at dress parade). Although it was a pivotal event in the history of the regiment, the historian, John L. Smith, completely ignored the incident and barely acknowledged that the feud between Gwyn and Donaldson existed.[13]

Likewise, Charles Stevens’s history of Berdan’s Sharpshooters brushed aside stories of his unit’s lackluster leadership. During the war, a universally despised commander, Colonel Hiram Berdan, led the Sharpshooters. In battle, Berdan routinely skulked in the rear. In autumn 1862, the regiment’s staff and line officers preferred charges against him for “conduct unbecoming” and “misbehavior before the enemy.” (In the end, Berdan was found “not guilty,” but only after he intimidated witnesses and tampered with evidence.) Tales of Berdan’s cowardice had been popular among the soldiers in 1862, but in 1892, they were virtually forgotten. The regimental historian, Stevens, purposely brushed aside Berdan’s slew of wartime faults, largely because his former commander had become active in the Sharpshooters’ veteran organization. In addition to helping organize the gatherings, Berdan promised to donate his personal fortune to erect a monument at Gettysburg. Unwilling to write a bad word against his former commander, Stevens wrote simply, “His [Berdan’s] military record as a Sharpshooter I have attempted to give impartially in the preceding pages.”[14]

Campaigns and battles constituted the majority of regimental historians’ narratives. Veteran-authors made every effort to weave the story of their regiment into the larger framework of the war’s military history, emphasizing the role their unit played in the Union army’s famous battles. Descriptions of combat varied according to the capabilities of the author. Some historians struggled to paint a realistic picture. For instance, the regimental association of the 20th Massachusetts hired a politician and Union army veteran, George Anson Bruce, to write their regiment’s history. Throughout the book, Bruce struggled to put the action into words. For instance, in describing the regiment’s charge at Marye’s Heights on December 13, 1862, Bruce said nothing about what the soldiers experienced—the sights, sounds, or smells of the battlefield. Instead, he relied on three dry, uninformative sentences lifted from the brigade commander’s after-action report.[15]

Bruce might be excused for his omissions, given that he was not a member of the 20th Massachusetts and no living veteran provided him with a first-hand account of the fight, but his problem was not an uncommon one. Regimental historians routinely relied upon letters from fellow veterans to piece together the stories of battle, and these became increasingly difficult to find as their comrades aged. As time passed, veterans died off or their memories became foggy. Useful anecdotes dried up and the horrors of battle faded. Consequently, some regimental histories transformed into uninteresting macro-histories, discussing military action by repeating the dry, stilted language found in the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. [16]

However, it would be inaccurate to say that all regimental historians uniformly shielded readers from the gruesome scenes of war. The conflict had left lasting impressions on a few writers who could not help but editorialize on the war’s violence. For instance, Captain Edwin E. Marvin described a gory moment from the Battle of Resaca in his 1889 history of the 5th Connecticut. Vividly, in gut-wrenching detail, he recalled how a shell decapitated two men and how the flying skull fragments sliced out the eyes of a nearby soldier, Private Thomas Graham. As Graham hobbled to the rear, with the flaccid remnants of his eyes dangling on his cheeks, he called for a lieutenant to take care of his gun. Hardly afraid of painting a picture of the inhuman scene for his readers, Marvin went on for several pages, telling them how to recognize importance of this moment in time:

If this picture could be imagined as it was, and as the comrades of poor Tommy saw it, then something of the true stuff of the man could be conceived, artillery roaring from all directions,—shells screeching past, and now coming so low that every one of them ricocheted along the ground and raked the earth from front to rear; a yelling line of rebels fast coming towards him, his eyes just closed forever to all the beauties of this earth and the glories of the skies, never to behold wife or children again, and still, when ordered to the rear in care of another, standing there with those sightless eyes dangling at his cheeks, and calling upon his officer to relieve him of his trusty gun, the last obligation remaining upon him, as he understood his duty to his country as a soldier; and then whoever can imagine this scene as it was, can begin to understand something of the truth and faithfulness of the nature of such private soldiers as Thomas Graham.[17]

Union regimental historians occasionally focused on the unsightly aspects of the war. Few authors failed to mention the ghastly scenes of a battlefield in its aftermath, something that could never be shaken from the tablets of memory. Lyman Jackman, historian of the 6th New Hampshire, described the piles of dead left at the Mule Shoe on Spotsylvania’s battlefield. He wrote, “As we came down into the open plain a most sickening sight presented itself. Here were the enemy’s dead, both men and horses, of the battle of the 12th, lying thick in all directions, and loathsomely swollen and disfigured. They were rapidly decomposing, having lain here six days in the warm sun and rain. We were obliged to pass directly over them, and we did so as quickly as possible, for it was impossible to breathe in that locality.”[18]

If unvarnished violence appeared, Union authors usually linked it to Confederate cruelty. Regimental historians often complained of unethical tactics and brutalities perpetrated by their foes. Stories of the killing of prisoners, thievery, and terrorism received wide play. In his regimental history of the 13th New Hampshire, S. Millett Thompson told a highly judgmental story taken from May 1863, explaining how his regiment lost a popular captain to the cruel calculations of an unseen Confederate sharpshooter. Harshly, Thompson contended that, “[Captain Buzzell’s] death falls upon the Regiment like a cold-blooded murder committed in their midst, not as a stroke of war.”[19]

Union regimental historians rarely held back when they spoke of barbarities associated with the Confederacy’s treatment of prisoners. John G. B. Adams, one of two historians who wrote about the 19th Massachusetts, dedicated half of his book to the story of prisoners—a predictable decision because nearly all of his regiment had been captured at the Jerusalem Plank Road on June 22, 1864. Adams did not spare any details describing the inhumane handling he received at various Confederate prison camps. Indeed, he pointed out, some Confederates “were making a war record by abusing us.”[20] Another author, Private Henry A. Harman of the 12th New York Cavalry, was equally bitter. He wrote his account serially in a newspaper that catered to Union veterans. With contempt, Harman described his incarceration at Andersonville by saying, “No words can express the terrible suffering which hunger and exposure inflicted upon the luckless inmates of rebel prisons. Most of them were calloused to all feelings of sympathy or humanity. Death had lost all its sanctity by its frequent occurrence, and not many cared how soon they became its prey… My health was entirely ruined, and my constitution broken by my year’s stay with the rebs.”[21]

Regimental historians did not mind discussing the collapse of slavery either; however, in terms of volume and quality of analysis, emancipation never rivaled the popular themes of patriotism, battle, and the inhumanity of the Confederates. Nevertheless, Union soldiers could scarcely avoid mentioning the progression of emancipation, and stories of freed slaves filled the pages of regimental histories anecdotally. For instance, while quartered at Point Lookout, the 12th New Hampshire lived next to a contraband camp that housed several thousand freed people. Asa Bartlett, the 12th New Hampshire’s adjutant and later its regimental historian, devoted several pages to describing the personalities and conditions of the freed people. He noticed the marks of cruelty that some slaves carried—scars and brands—admitting that some were “all broken to pieces from cruel and abusive treatment while in bondage.”

Bartlett was savvier than most writers in that he recognized the significance of freedom to the freed people, the importance of their impending citizenship. Most of the contraband, he wrote, “bore no such marks of cruelty, and acknowledged that they were very well treated and cared for by their masters; and when asked why then they ran away, would respond: ‘Cause, Massa, I wants to be free.’” Bartlett continued: “A visit to this camp was much pleasing, more instructive, and most interesting. One of the leading manifestations of these people was their eagerness to learn to read; and the rapid progress they made was scarcely less surprising. The old would vie with the young to improve this first privilege of their lives to acquire the rudiments of that knowledge which they seemed to feel and know had given the whites their superiority over them, and a want of which was the chief cause of their degraded condition.” Looking back from the year 1897, he could see how the Civil War had truly constituted a revolutionary moment for African American history.[22]

Confederate veterans also wrote regimental histories during the postwar period, although their numbers did not match the numbers of their northern counterparts. According to Lester and Hydrick, the largest Confederate state, Virginia, produced only 316 unit histories and veteran-authored memoirs, less than half of the number produced by the North’s most prolific state, New York. Other Confederate states—even those central to the war effort—produced significantly fewer histories. South Carolina produced only ninety-six, Texas only eighty-nine, and Alabama only seventy-two. By comparison, the smallest northern state, Rhode Island, produced 167 histories and memoirs.[23]

Although fewer in number, Confederate regimental histories were not much different from those produced in the North. Confederate authors filled their pages with nostalgia, propaganda, and overly charitable memories. Thomas A. Head, the author of the 16th Tennessee’s regimental history, for instance, defined his book as an attempt to do justice to the memory of his fallen comrades and accentuate their “heroic deeds.” He wrote, “They were brave men and true patriots. They were honest in their convictions of right, and true to their plighted faith. Upon their record is no stain of treason. Their names are to be defended and handed down unsullied to all future generations.” Writing in 1885, Head supposed, “That they were brave men and true to their plighted faith has never been questioned, even by their enemies.”[24]

Confederate historians defended their cause as resolutely as the Union historians defended theirs. William Morgan, author of the 11th Virginia’s regimental history, spoke for many ex-Confederates when he wrote, “We suffered and sacrificed all save honor, and thousands of our comrades died for a cause which we knew and still know was just and right and holy.”[25] Henry Walter Thomas, the author of the history of the Doles-Cook Brigade, remarked, “For our participation in this struggle we have no apologies to make, for our cause was just and holy.”[26] Like their northern counterparts, Confederate authors took a one-sided view of the coming of the war, placing all blame on their enemies. Augustus Dickert, the author of a history of Kershaw’s Brigade, wrote, “For years the North had been making encroachments upon the South; the general government grasping, with a greedy hand, those rights and prerogatives, which belonged to the States alone, with a recklessness only equaled by Great Britain towards the colonies.”[27]

Naturally, Confederate veterans described the coming of the war in sectional terms, but they often resorted to stilted logic to fashion their defense. The demise of slavery forced Confederate writers to manufacture a more wholesome reason for fighting, and to that end, they propagated the myth of “States Rights.” In his history of the 11th Virginia, William Morgan argued that the war had nothing to do with slavery, that Secession had been motivated by an esoteric desire to test the validity of state power. Of course, Morgan could not square that inconsistency with the Confederacy’s adherence to white supremacy. A few sentences after explaining what States Rights meant, Morgan reminded readers that racism motivated many Confederate citizens to take up arms. He declared, “To make the highest type of the Anglo-Saxon subject to the African! Ye gods! What a crime was attempted! . . . This, if nothing else, justified the South in its attempt at separation from the North.”[28] Dickert’s history of Kershaw’s Brigade was similarly convoluted, waffling between a farcical love of States Rights and a real love of white supremacy. Dickert stated flatly that the real cause of the war “was far removed from the institution of slavery.” However, when he finally explained what drove his home state to secede, Dickert confirmed that the rise of the Republican Party and Abraham Lincoln “whose avowed purpose was the liberation of the slaves, regardless of the consequences,” had caused South Carolina’s politicians to call for a secession convention.[29]

If Confederate regimental histories demonstrated any major difference from their Union counterparts, it came when they attempted to explain Confederate defeat. While Union writers uniformly believed that a spirit of righteousness led them to victory, Confederate historians lacked a similar sense of unity when explaining their country’s downfall. Hard-pressed to find a palatable reason to describe the collapse of the Confederacy, regimental historians from the South came up with wildly different opinions. For instance, Augustus Dickert confirmed that the spirit of the South had never been broken, saying that, “The South could not be conquered by defeat.” [30] To Dickert, the Confederacy ran out of men and resources, even though its people still had the spirit to fight on. Meanwhile, John Worsham, a memoirist who served in the 21st Virginia, believed that the Union’s armed forces had killed the Confederacy’s enthusiasm, confirming that by April 1865, “The inhabitants of the South were a ruined people.”[31]

When describing the military causes of the defeat, postwar Confederate writers offered several opinions. Some writers argued that the Confederacy had been doomed by the government’s failure to secure a European ally. When Wendell D. Croom wrote his history of the 6th Georgia, he claimed, “The cause for which they had so long defended with a zeal and determination unknown to any people of modern times, had now, without the intervention of a negotiating umpire, to be abandoned and forever lost; as the sword, the great arbiter of the contest had decided against them.”[32] Other peculiar theories arose—including undue criticism of Jefferson Davis and his generals, complaints against overly-cruel Union tactics, and strange quirks of fate. However, most postwar writers found it easiest to say that preponderating numbers of Union troops had simply overwhelmed the much smaller Confederate armies, an idea that stemmed from Robert E. Lee’s farewell order to his army, published on April 10, 1865. Although generalship and hard fighting—not numbers—more often determined the outcome of battles, Confederate writers preferred to believe that the odds were stacked against them, even from the beginning.[33]

The meaning of the defeat varied widely as well. Some writers found it easy to dismiss the Confederacy’s failure as a simple case of history falling on the side of the winners. A Virginia author who served in the Stonewall Brigade wrote, “The only thing right about secession is whether the party who secedes are able numerically and financially to carry out their designs; if they are it is all right, in the eyes of the world; if not, it is all wrong.”[34] Seldom did Confederate writers describe their defeat for what it truly was—their failure to maintain a slave society under the protection of a republican government. Confederate writers who wrote with honesty tended to see the war as anything but uplifting for their cause. Charles Irvine Walker, an officer with a South Carolina regiment, recollected, “We must bow to the will of God and feel that all is for the best. And although we cannot see the good to us in this terrible crushing of our noblest hopes and aspirations, yet there must be good.” The slaveholders’ republic had failed at the cost of 260,000 Confederate soldiers and sailors. Hoping that history’s path might set things more favorably to the cause of white supremacy, Walker closed his 1881 history of the 10th South Carolina with the hope: “God grant that the benefit to result from this mighty sacrifice, if not coming to us may fall upon the children of the men of that grand old corps—the Tenth Regiment South Carolina Volunteers.”[35]

Although the last confirmed Civil War veteran died in 1956, unit histories continued to be published in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. By that point, they belonged to the realm of professional historians, and they remain so to this day. In many ways, modern regimental histories follow the same scheme as their postwar counterparts. They describe a regiment’s history from start to finish, emphasizing its battle action and campaigns. However, a few key differences separate them from the histories written by veterans. Modern regimental histories are more analytical, and do not rely solely upon narrative to tell the story of the regiment. They attempt to incorporate social history into their portrayal of the day-to-day lives of soldiers, often analyzing the occupations, age, and class-status of the enlisted ranks to give readers a sense of how regiments reflected the communities that raised them. Also, modern regimental histories tend to discuss the politics of command. For Union regiments, at least, this requires historians to emphasize the partisan war between Republicans and Democrats in matters of promotion and civil-military relations.

Modern regimental histories rarely shy away from the unappealing aspects of war, and they often include discussions of soldiers’ relationships with commercialized sex, desertion, military execution, courts-martial, and cowardice. For instance, Leslie Gordon’s 2014 history of the 16th Connecticut referred to the unit as a “broken regiment,” since more than one-third of it spent the war inside Confederate prisons. The survivors, she wrote, “came home physically and emotionally broken and scarred from the trials of war.” Likewise, Edwin P. Rutan, II did not sugar-coat his recent 2015 history of the 179th New York, reminding readers that many soldiers joined that regiment because of the expensive bounty that accompanied it.[36] In his history of the 58th North Carolina, Michael C. Hardy concluded that the regiment fought well, but it could have been better, because “it was plagued by desertion and a lack of competent commanders, in addition to the almost total abandonment by its home state which led to shortages in clothing and other munitions, to leading in turn to other declines in morale.”[37] Finally, modern historians rarely end their story in 1865. Instead, they take pains to discuss the lives of veterans, their postwar readjustments, and their commemorative exercises.

In sum, “new regimental history” is in full bloom. Edward Hagerty, the author of an excellent study of Collis’s Zouaves published in 1997, summed the recent improvements of genre: “Because authors have relied on a wider scope of source materials and have made more detached observations, the resulting works tend to be of quality superior to that of their predecessors.”[38]

Currently, Civil War regimental histories show no signs of stopping. As there were thousands of regiments, and hundreds currently without a history at all, we should expect the subgenre to remain vibrant and popular. Regimental histories are troublesome sources, but they cannot be avoided by dedicated students of the war. They constituted some of the first histories of the war, and arguably the most important. If war is—at its simplest—the terrible tragedy of killing and dying, it is necessary to discuss the day-to-day lives of the men who killed and died between 1861 and 1865.

- [1] Asa W. Bartlett, History of the Twelfth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (Concord, NH: Ira C. Evans, Printer, 1897), vi.

- [2] Most likely, the first single-volume history was William P. Maxson’s Camp Fires of the Twenty-third, a 196-page account of a two-year regiment recruited in western New York, which appeared in the summer of 1863. William P. Maxson, Camp Fires of the Twenty-Third: Sketches of the Camp Life, Marches, and Battles of the Twenty-Third Regiment, N. Y. V., During the Term of Two Years in the Service of the United States (New York: Davies & Kent, Printers, 1863).

- [3] Richard Eddy, History of the Sixtieth Regiment, New York State Volunteers (Philadelphia, PA: Published by the Author, 1864), v-vi.

- [4] William P. Lloyd, History of the First Reg’t. Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry from its Organization, August, 1861, to September, 1864, with List of Names of all Officers and Enlisted Men Who Have Ever Belonged to the Regiment, and Remarks Attached to Each Name, Noting Change, &c. (Philadelphia, PA: King and Baird Printers, 1864), un-paginated preface.

- [5] Evan Morrison Woodward, Our Campaigns: The Second Regiment Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteers, or, the Marches, Bivouacs, Battles, Incidents of Camp Life and History of Our Regiment During its Three Years Term of Service Together With a Sketch of the Army of the Potomac, Under Generals McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, Meade, and Grant (Philadelphia, PA: J. E. Potter, 1865), 187.

- [6] Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885-1886); William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman by Himself, 2 vols (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1875); Alexander K. McClure, The Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times (Philadelphia, PA: The Times Publishing Company, 1879); Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Being for the Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon” The Century War Series”, 4 vols. (New York: The Century Co. 1884-1888), based on “The Century War Series” in The Century Magazine, November 1884 to November 1887.

- [7] David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 170.

- [8] Robert Lester and Blair Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, Parts 1-4 (Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993).

- [9] Osmund Rhodes Howard and William H. Rauch, History of the “Bucktails,” Kane Rifle Regiment if the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps (13th Pennsylvania Reserves, 42nd of the Line) (Philadelphia, PA: Electric Printing Company, 1906), 1-2.

- [10] John Day Smith, History of the Nineteenth Maine Volunteer Infantry, 1862-1865 (Minneapolis, PA: Great Western Printing Company, 1909), 1.

- [11] Charles A. Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (St. Paul, MN: Price-McGill Co., 1892), 1.

- [12] E. Jay Allen, et. al., Under the Maltese Cross: Antietam to Appomattox, the Loyal Uprising in Western Pennsylvania, 1861-1865; Campaigns 155th Pennsylvania Regiment, Narrated by the Rank and File (Pittsburg, PA: The 155th Regimental Association, 1910), 44-45.

- [13] John L. Smith, History of the Corn Exchange Regiment, 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, From their First Engagement at Antietam to Appomattox (Philadelphia, PA: J. L. Smith, Publisher, 1888), 639. Smith hinted at the feud briefly, but took Donaldson’s side, an unsurprising decision given that Smith used Donaldson as a source for his anecdotes. Speaking of Gwyn in his biography chapter, Smith wrote, “He was by nature impulsive and sometimes revengeful, with likes and dislikes… strong and exacting. These traits won him many warm friends, and at the same time made him many bitter enemies in the regiment.”

- [14] Stevens, History of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, 526.

- [15] George Anson Bruce, The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865 (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1906), 216.

- [16] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols. in 128 parts (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901),

- [17] E. E. Marvin, The Fifth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers: A History Compiled from Diaries and Official Records (Hartford, CT: Wiley, Waterman, and Eaton, 1889), 301-2.

- [18] Lyman Jackman, History of the Sixth New Hampshire Regiment in the War for the Union (Concord, NH: Republican Press Association, 1891), 251.

- [19] S. Millett Thompson, The Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry In the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin and Company, 1888), 144.

- [20] John Gregory Bishop Adams, Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment (Boston MA: Wright and Potter Printing Company, 1899), 114.

- [21] National Tribune, June 22, 1893.

- [22] Bartlett, History of the Twelfth Regiment, 166.

- [23] Lester and Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories, Part 1.

- [24] Thomas A. Head, Campaigns and Battles of the Sixteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteers, in the War Between the States, With Incidental Sketches of the Part Performed by Other Tennessee Troops in the Same War, 1861-1865 (Nashville, TN: Cumberland Presbyterian Printing House, 1885), 10.

- [25] William H. Morgan, Personal Reminiscences of the War of 1861-1865, In Camp—En Bivouac—On the March—On Picket—On the Skirmish Line—On the Battlefield—and in Prison (Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell and Company, 1911), 13.

- [26] Henry Walter Thomas, History of the Doles-Cook Brigade, Army of Northern Virginia, C.S.A. (Atlanta, GA: Franklin Printing and Publishing Company, 1903), vi.

- [27] D. Augustus Dickert, History of Kershaw’s Brigade with Complete Roll of Companies, Biographical Sketches, Incidents, Anecdotes, Etc. (Newberry, SC: Elbert H. Aull Company, 1899), 9.

- [28] Morgan, Personal Reminiscences, 28.

- [29] Dickert, History of Kershaw’s Brigade, 9-12.

- [30] Dickert History of Kershaw’s Brigade, 525.

- [31] John Worsham, One of Jackson’s Foot Cavalry: His Experience and What He Saw During the War, 1861-1865 (New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1912), 291.

- [32] Wendell D. Croom, The War-History of Company “C” (Beauregard Volunteers), Sixth Georgia Regiment With a Graphic Account of Each Member (Fort Valley, GA: Fort Valley Advertiser Office, 1879), 32.

- [33] Richard N. Current, “God and the Strongest Battalions,” in David H. Donald, ed., Why the North Won the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1960), 15-32; David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War and American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 255-98; Gary W. Gallagher, Causes, Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 16-40; Headquarters, Army of Northern Virginia, 10th April 1865.General Order No. 9After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.I need not tell the survivors of so many hard fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them.But feeling that valour and devotion could accomplish nothing that could compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest, I have determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen.By the terms of the agreement, officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you his blessing and protection.With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your Country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for myself, I bid you an affectionate farewell.— R. E. Lee, General, General Order No. 9From Lee, Robert E., Jr, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee. (New York: Doubleday Page and Company, 1904), 153-4.

- [34] John Overton Casler, Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade (Girard, KS: Appeal Publishing Company, 1906), 299-300

- [35] C. I. Walker, Rolls and Historical Sketch of Tenth Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, in the Army of the Confederate States (Charleston, SC: Walker, Evans, and Cogswell, 1881), 137-8.

- [36] Leslie J. Gordon, A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014), 2; Edwin P. Rutan “If I Have Got To Go and Fight, I Am Willing.”: A Union Regiment Forged in the Petersburg Campaign: The 179th New York Volunteer Infantry 1864-1865 (Park City, UT: RTD Publications, 2015).

- [37] Michael C. Hardy, The Fifty-Eighth North Carolina Troops: Tar Heels in the Army of Tennessee (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2010), 188

- [38] Edward J. Hagerty, Collis’ Zouaves: The 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), xiii.

If you can read only one book:

Lester, Robert and Blair Hydrick. Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, 4 parts. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993.

Books:

Adams, John Gregory Bishop. Reminiscences of the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment. Boston, MA: Wright and Potter Printing Company, 1899.

Allen, E. Jay et. al., Under the Maltese Cross: Antietam to Appomattox, the Loyal Uprising in Western Pennsylvania, 1861-1865; Campaigns 155th Pennsylvania Regiment, Narrated by the Rank and File. Pittsburg, PA: The 155th Regimental Association, 1910.

Bartlett, Asa W. History of the Twelfth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion. Concord, NH: Ira C. Evans, Printer, 1897.

Bruce, George Anson. The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1906.

Casler, John Overton. Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade. Girard, KS: Appeal Publishing Company, 1906.

Croom, Wendell D. The War-History of Company “C” (Beauregard Volunteers), Sixth Georgia Regiment with a Graphic Account of Each Member. Fort Valley, GA: Fort Valley Advertiser Office, 1879.

Dickert, D. Augustus. History of Kershaw’s Brigade with Complete Roll of Companies, Biographical Sketches, Incidents, Anecdotes, Etc. Newberry, SC: Elbert H. Aull Company, 1899.

Eddy, Richard. History of the Sixtieth Regiment, New York State Volunteers. Philadelphia, PA: Published by the Author, 1864.

Gordon, Leslie J. A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Hagerty, Edward J. Collis’ Zouaves: The 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

Hardy, Michael C. The Fifty-Eighth North Carolina Troops: Tar Heels in the Army of Tennessee. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2010.

Head, Thomas A. Campaigns and Battles of the Sixteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteers, in the War Between the States, With Incidental Sketches of the Part Performed by Other Tennessee Troops in the Same War, 1861-1865. Nashville, TN: Cumberland Presbyterian Printing House, 1885.

Howard, Osmund Rhodes and William H. Rauch. History of the “Bucktails,” Kane Rifle Regiment if the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps (13th Pennsylvania Reserves, 42nd of the Line). Philadelphia, PA: Electric Printing Company, 1906.

Jackman, Lyman. History of the Sixth New Hampshire Regiment in the War for the Union. Concord, NH: Republican Press Association, 1891.

Lloyd, William P. History of the First Reg’t. Pennsylvania Reserve Cavalry from its Organization, August, 1861, to September, 1864, with List of Names of all Officers and Enlisted Men Who Have Ever Belonged to the Regiment, and Remarks Attached to Each Name, Noting Change, &c. Philadelphia, PA: King and Baird Printers, 1864.

Marvin, E. E. The Fifth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers: A History Compiled from Diaries and Official Records. Hartford, CT: Wiley, Waterman, and Eaton, 1889.

Maxson, William P. Camp Fires of the Twenty-Third: Sketches of the Camp Life, Marches and Battles of the Twenty-Third Regiment, N. Y. V., During the Term of Two Years in the Service of the United States. New York: Davies & Kent, Printers, 1863.

Morgan, William H. Personal Reminiscences of the War of 1861-1865, In Camp—En Bivouac—On the March—On Picket—On the Skirmish Line—On the Battlefield—and in Prison. Lynchburg, VA: J. P. Bell and Company, 1911.

Rutan, Edwin P. “If I Have Got To Go and Fight, I Am Willing.”: A Union Regiment Forged in the Petersburg Campaign: The 179th New York Volunteer Infantry 1864-1865. Park City, UT: RTD Publications, 2015.

Smith, John Day. History of the Nineteenth Maine Volunteer Infantry, 1862-1865. Minneapolis, MN: Great Western Printing Company, 1909.

Smith, John L. History of the Corn Exchange Regiment, 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, From their First Engagement at Antietam to Appomattox. Philadelphia, PA: J. L. Smith, Publisher, 1888.

Stevens, Charles A. Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865. St. Paul, MN: Price-McGill Co., 1892.

Thomas, Henry Walter. History of the Doles-Cook Brigade, Army of Northern Virginia, C.S.A. Atlanta, GA: Franklin Printing and Publishing Company, 1903.

Thompson, S. Millett. The Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin and Company, 1888.

Walker, C. I. Rolls and Historical Sketch of Tenth Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, in the Army of the Confederate States. Charleston, SC: Walker, Evans, and Cogswell, 1881.

Woodward, Evan Morrison. Our Campaigns: The Second Regiment Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteers, or, the Marches, Bivouacs, Battles, Incidents of Camp Life and History of Our Regiment During its Three Years Term of Service Together With a Sketch of the Army of the Potomac, Under Generals McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, Meade, and Grant. Philadelphia, PA: J. E. Potter, 1865.

Worsham, John. One of Jackson’s Foot Cavalry: His Experience and What He Saw During the War, 1861-1865. New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1912.

Organizations:

No organizations listed.

Web Resources:

U.S. Civil War Regimental Histories in the Library of Congress contains lists of regimental histories. However, the interface for finding them has been superseded so that users need to first identify a unit from the LOC listing, then use the LOC main search function to find copies accessible online or in libraries.

Dyer’s Compendium of the War of the Rebellion is a list of regiments organized by state with summary descriptions of each regiment and its service. The listing is comprehensive for Union regiments and incomplete for Confederate regiments.

Lester, Robert and Blair Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, 4 parts. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993 is available online in microfiche.

Part 1. The Confederate States of America and Border States.

Lester, Robert and Blair Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, 4 parts. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993 is available online in microfiche.

Part 2. The Union—New England.

Lester, Robert and Blair Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, 4 parts. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993 is available online in microfiche.

Part 3. The Union—Mid-Atlantic.

Lester, Robert and Blair Hydrick, Civil War Unit Histories: Regimental Histories and Personal Narratives, 4 parts. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1993 is available online in microfiche.

Part 4. The Union—Midwest and West.

This New York State Archives website contains regimental histories of all Civil War New York regiments and military units.

Other Sources:

Obtaining Inexpensive Copies of Regimental Histories

Inexpensive reprints of regimental histories can be purchased from Higginson Book Company LLC.

Obtaining Inexpensive Copies of Regimental Histories

Inexpensive reprints of regimental histories can be purchased from Butternut and Blue

C. Clayton Thompson Bookseller

C. Clayton Thompson Bookseller specializes in Civil War regimental histories and offers a very long list of titles sorted by state. Their address is:

C. Clayton Thompson - Bookseller

584 Briarwood Lane

Boone NC 28607