Riverine Warfare

by Dwight S. Hughes

The contest for the Mississippi River and its tributaries involved specialized classes of war vessels commanded and manned by naval personnel and coordinating operations with the army. In tactics and technology, however, riverine warfare was a new concept. Union waterborne assets would be required to transport and sustain major land forces, conduct amphibious expeditions and sieges, interdict enemy trade, communications, and transportation, and protect friendly commerce. Wooden and ironclad river steam-powered gunboats would confront enemy counterparts, powerful fortifications, heavy artillery, torpedoes (mines), and guerrillas. At first the Union converted existing commercial vessels into gunboats, but soon designed new vessels from the keel up. Their armor was suboptimal, maneuverability restricted. They were vulnerable to torpedoes (mines) and ramming. The union-built ironclads, timberclads and an ad hoc fleet of various smaller gunboats and river steamers were used to patrol, escort, transport, and communicate through Confederate occupied territory on the rivers. The first joint army-navy expedition saw Flag Officer Andrew Foote cooperating with Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant to capture Fort Henry on the Tennessee River then Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River in February 1862. Breaking the long Confederate line in the west, their capture led to the abandonment of Kentucky and most of Middle Tennessee by the Confederates. In the spring of 1862 Federal forces thrust up the Mississippi from New Orleans and down it to Island No. 10. The attacks involved newly constructed mortar gunboats, which proved to be less than fully useful. Island No. 10 fell on April 8 and New Orleans was captured on April 24. On June 6, 1862 on the Mississippi at Memphis TN, a Union force of ironclads and converted rams confronted a Confederate force of converted vessels. The Confederate force, unarmored and outgunned, was destroyed. In August 1862 during the failed first attempt by Union forces to take Vicksburg, the Confederate ironclad Arkansas confronted the federal fleet and with failing engines and under murderous fire was abandoned and destroyed, ending the Confederate naval presence on the Mississippi. During the winter and into the spring of 1863, Federal forces under General Grant and coordinating with Admiral Porter maneuvered to take Vicksburg, which fell July 4, 1863. Port Hudson, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi, fell on July 9. The combined army-navy campaigns opened the Mississippi River along its entire length, severing the Confederacy in two. “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” wrote Abraham Lincoln. The brown-water navy of the Mississippi River Squadron kept busy for two additional years fighting Rebel guerrillas, suppressing enemy trade, and protecting friendly commerce.

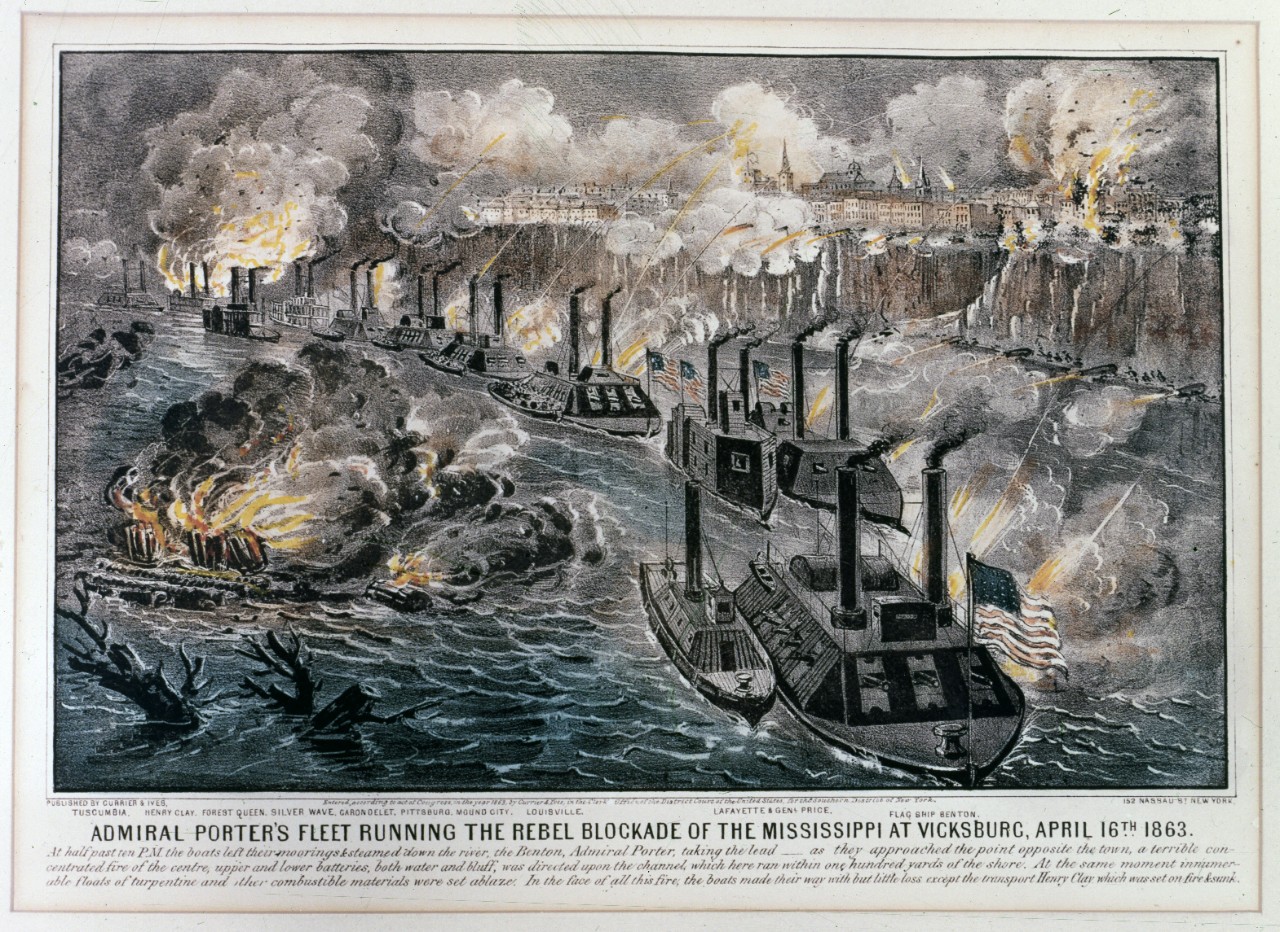

"Admiral Porter's Fleet Running the Rebel Blockade of the Mississippi at Vicksburg, April 16th 1863."

Image courtesy of the U.S. Naval Academy Museum, Beverley R. Robinson Collection. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Catalog #: NH 76557-KN

History offers few examples other than the American Civil War and the conflict in Vietnam, of extensive military operations on inland waterways requiring specialized classes of war vessels commanded and manned by naval personnel. The contest for the Mississippi River and its tributaries—the spine of America—was one of the longest and most challenging campaigns of the Civil War encompassing a 700-mile wet corridor from Mound City, Illinois, to the Gulf of Mexico.

Control of the rivers was a key strategic factor from the beginning as specified in Lieutenant General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan[1] to surround and strangle the Confederacy. On June 10, 1862, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote to his wife Ellen: “I think the Mississippi the great artery of America, whatever power holds it, holds the continent.” The new commander-in-chief, himself a product of the heartland, understood the rivers. As a young man, Abraham Lincoln barged down the Ohio and the Mississippi to New Orleans experiencing firsthand these vital north-south arteries of transportation and commerce at a time when railroads had not established extensive east-west networks.[2]

Unschooled as he was in military matters, the president intuitively grasped strategic concepts including the importance of isolating rebellious states. Lincoln’s first major decision—one week after the fall of Fort Sumter—declared a blockade of Southern ports as the primary mission of the United States Navy. The concept of blockade logically extended up the mighty rivers slicing through the vitals of the Confederacy. Lincoln also pushed for major coordinated advances on multiple fronts, east and west, taking advantage of the Union’s superior numbers and resources.

In tactics and technology, however, riverine warfare was a new concept. Union waterborne assets would be required to transport and sustain major land forces, conduct amphibious expeditions and sieges, interdict enemy trade, communications, and transportation, and protect friendly commerce. Wooden and ironclad river gunboats would confront enemy counterparts, powerful fortifications, heavy artillery, torpedoes (mines), and guerrillas.

Rivers and oceans are quite different environments; the vehicles and skills required to exploit them differed accordingly. The millennia-old technology of sail still ruled open water. Although rapidly developing, steam engines were not sufficiently reliable, robust, or efficient to be the primary, much less the only, form of propulsion over wide oceans and so they remained auxiliary to wind.

Conversely, river craft relied solely on steam power where wind would not work. They operated along swift flowing, shifting, meandering, constricted, shallow, sand banked, and snag infested rivers and swamps. Most army and navy officers considered their professions as disparate preserves of land and sea bounded by the hightide mark. Neither service was versed in the relatively new business of steam rivermen. Both navies, Union and Confederate, started with no shallow-water warships, no tactics, no command structure, no infrastructure.

With Lincoln’s urging, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton created a robust riverine force from nothing and—usually—coordinated on strategy. But below the commander-in-chief, there was no joint army-navy commander, no joint staff, and no protocols or mechanisms for directing joint operations. Traditionally, the officers of one service, however senior, could issue no orders to an officer of the other service, however junior. Operational coordination depended on the willingness and abilities of commanders in the field to plan and execute together, efforts frequently impeded by interservice cultural differences and jealousies of rank.

Despite this lack of joint perspective, a few outstanding leaders emerged. Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote, Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis, and Admiral David Dixon Porter developed effective partnerships with army counterparts, particularly General Ulysses S. Grant, also a son of the West. From his first battle to the last, Grant appreciated the navy. He readily incorporated naval elements as integral combat and logistical arms and he credited them as critical factors in his victories.

In May 1861, Secretary Welles appointed Commander John Rodgers as senior navy advisor in the west. He would report to the commander of the Department of the Ohio, Major General George Brinton McClellan, in regard to “establishing a naval armament on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers…with a view of blockading or interdicting communication and interchanges with the States that are in insurrection.” Rogers was to “aid, advise, and cooperate” with army commanders “in crossing or navigating the rivers or in arming and equipping the boats required.” McClellan would issue orders and sign requisitions; Rogers would act “in conjunction with and subordinate to him.”[3]

Rodgers worked out of Cincinnati, Ohio, to purchase three commercial paddle steamers and contract for their conversion as gunboats. Boilers and steam pipes were lowered from the main deck into the hold; high superstructures were removed and replaced with 5-inch thick oak bulwarks; sides were pierced, and decks strengthened for six or eight naval artillery pieces. He recruited navy crews from rivermen, local landsmen, and the army. The USS Conestoga, USS Tyler, and USS Lexington were the first commissioned United States warships dedicated to river conflict. They became known as timberclads.

Commander Rogers (equivalent in rank to an army major) proceeded on his own initiative with no instructions, no plans, and initially no army funding. He would be rebuked by Secretary Wells for overstepping his advisory role, but these small, powerful vessels saw more service than any other gunboats in theater.

The next step was to design and build gunboats from the keel up, producing the first uniform class of river war vessels and the first U.S. ironclads to enter combat. James Buchanan Eads, a wealthy St. Louis industrialist and self-taught naval engineer, obtained an army contract and risked his fortune to fund the venture. Eads also was an exceptional river navigator. He would become a world-renowned civil engineer and inventor.

Noted naval constructor Samuel Moore Pook designed these unprecedented vessels with shallow, wooden river hulls, armored decks, an armored, slope-sided shed or casemate mounting 13 to 16 guns, and a steam engine driving a covered paddlewheel. Named after river cities (with one exception), they were called city-class ironclads or Eads gunboats, or for their appearance, Pook turtles. The seven ironclads effectively integrated firepower, protection, and mobility but with defects.

The armor was suboptimal. Maneuverability was restricted. They had no watertight compartments to isolate flooding. They were vulnerable to torpedoes, which would sink the USS Cairo and Baron De Kalb, and to ramming, which would sink (if only briefly) the USS Cincinnati and Mound City. The city-class ironclads became the backbone of the river flotilla taking part in every significant action on the upper Mississippi and its tributaries.

A few converted ironclads included the USS Benton, a huge center-paddlewheel catamaran snag boat built to clear downed trees (snags) from the river and the USS Essex, along with smaller and partly armored gunboats. Dozens of flat-bottomed river steamers were purchased and armed—but not armored—to patrol, escort, transport, and communicate through hundreds of miles of occupied territory. On some of them, tin sheeting provided small arms protection, hence tinclads. The luxurious sidewheeler USS Black Hawk was a command ship. This ad-hoc fleet became the Western Gunboat Flotilla, an unprecedented joint service organization.

Flag Officer[4] Andrew Hull Foote succeeded Commander Rodgers in August 1861, taking over the largely undefined role of supervising the army’s navy, now under Major General John C. Frémont commanding the Department of the West. The expanding flotilla was an orphan organization foreign to all existing command and logistical procedures in both services. Frémont could not provide adequately for his own soldiers and felt no obligation to pay a bunch of sailors. Secretary Welles was focused on the immense warship procurement program for an almost impossible continent-wide coastal blockade. He agreed to provide naval artillery and navy officers to the river flotilla, but otherwise the army was on its own in the hinterland. Foot’s urgent requirements for shot and shell became mired between service bureaucracies.

The president fired General Frémont in November 1861, assigning Major General Henry Wager Halleck to command in the west. In January 1862, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant convinced Halleck to let him seize the initiative in middle Tennessee moving against Forts Henry on the Tennessee River and Donelson on the Cumberland. The forts were vulnerable positions central to the thin Confederate defensive line stretching from Arkansas to the Cumberland Gap. Foote and Grant formed a potent army-navy team, first against Fort Henry.

Grant sent Foote up the Tennessee with four ironclads (Cincinnati, Carondelet, St. Louis, and Essex) and the three timberclads (Conestoga, Tyler, and Lexington) while river transports deposited 15,000 men in two divisions on both banks three miles below the fort. The gunboats were to suppress the fort’s batteries with their heavy, mobile artillery while troops marched up and assailed the earthen works. Fort Henry was situated on low, swampy ground dominated by hills across the river, designed primarily to impede water traffic. The fort mounted eleven guns of various caliber with unobstructed fields of fire two miles downriver. Confederates also anchored torpedoes in the channel, but they were neutralized by high water and leaks in the metal containers.

On February 6, 1862, Foote deployed his newly designed, hastily constructed ironclads in line abreast and chugged upriver followed by the timberclads. Fort and gunboats exchanged volleys for over an hour with the ironclads taking numerous hits. Most bounced off, but a 32-pound shot penetrated the armor on Essex, hit a boiler, and blew scalding steam through the ship causing 32 casualties. Fortunately, the damaged vessel could fall back downriver with the current. Heavy rains the night before had raised the river level inundating most of the fort including the powder magazine; accurate naval gunfire knocked out all but one remaining gun. Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman surrendered Fort Henry to the Union navy before the army arrived.

Flag Officer Foote immediately sent the three timberclads—which were undamaged, faster, and more maneuverable than the ironclads—on up the Tennessee. They destroyed the Memphis and Ohio Railroad bridge, cutting communications between Confederate field armies forcing them to withdraw. They captured and destroyed Rebel vessels, including an ironclad under construction, and took hundreds of tons of supplies. The raid reached as far as Muscle Shoals, Alabama, the river's navigable limit.

Grant pursued the fleeing Rebels 12 miles overland to Fort Donelson while Foot withdrew his gunboats down the Tennessee, turned up the Ohio River, and then up the Cumberland to approach the fort from the water. Fort Donelson was more formidable than Fort Henry, mounting 12 guns in river batteries 100 feet above the water serving plunging fire against attackers. Foote was reluctant to proceed without thorough reconnaissance while an anxious Grant urged him to advance.

Foote closed with the fort on February 14 and commenced fire; his ironclads were pummeled by Rebel shells and forced to withdraw with heavy damage. The flag officer was wounded in the foot. Historians speculate that Foote should either have bombarded the fort from the relative safety of longer range or run on by the batteries and attacked from the defenseless upriver flank. His flotilla still controlled the river but was out of the fight. “Unconditional Surrender”[5] Grant battered the Confederates into capitulation, bagging an entire field army and beginning his rise to supreme command.

Together Foote and Grant blew open the Confederacy’s heartland. Rebel armies abandoned all of Kentucky—which was preserved for the Union—and most of middle Tennessee along with crucial economic resources such as iron and pork. Wet highways opened along the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers into eastern Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and northern Alabama, exposing the manufacturing and arsenal city of Nashville, setting the stage for the Battle of Shiloh, and leading on finally to Chattanooga. In stark contrast to General McClellan’s failure in the Peninsula Campaign that spring, Forts Henry and Donelson ranked among the deadliest strategic strokes and the greatest Confederate supply disasters of the war. Waterborne mobility and firepower were decisive factors.

The Western Gunboat Flotilla was no longer an orphan. Secretary Welles began to see it as a navy asset while Secretary of War Stanton and department commander General Halleck became supportive; even General-in-Chief McClellan took renewed interest. But continued disagreements and disconnects between Halleck, Welles, and Foote forced the commander-in-chief himself to serve as joint field commander. From the White House, Lincoln issued instructions down to the movements of individual ships and ordering of guns and supplies. The frustrated flag officer would have preferred to operate independently of the army, subject only to orders of his secretary and president just as the navy operated on the coasts.

By March 1862, the Union seemed to be on the move everywhere following President Lincoln’s strategy and forcing the enemy to counter widespread, simultaneous advances along exterior lines. While McClellan advanced toward Richmond via the Peninsula, in the west, Confederates faced attack from three directions. Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut took command of the Gulf Blockading Squadron and prepared to attack New Orleans followed by a thrust north up the Mississippi River. General Grant boarded steam transports and proceeded south upstream on the Tennessee River toward Pittsburg Landing in southwest Tennessee. He was accompanied by timberclads Lexington and Tyler, whose big guns would cover reinforcements crossing over, keep river supply lines open, and help stop the climatic Confederate charge at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6.

Meanwhile, in conjunction with Brigadier General John Pope’s Army of the Mississippi, Flag Officer Foote proceeded down the Big Muddy with the rest of the flotilla toward Island No. 10, the northern-most Confederate bastion defending the mighty river. Island No. 10 (tenth island south of the Mississippi-Ohio River junction) was an enlarged sandbar with 7,000 Rebels and five batteries mounting 24 guns. It was well situated near the Tennessee shore at the bottom of the first of two-horseshoe bends where the river reversed 180 degrees from south to north and south again. Attacking gunboats were exposed bows on for several miles and again when slowing for the tight right turn. The Rebel emplacement was flanked by impassable swamps to the east, but also dependent on a single road for supplies and reinforcements.

At the top of the western and northern river bend sat the town of New Madrid, Missouri. Pope came from the west and pushed Rebels out of New Madrid but could advance no farther. Flag Officer Foote was hesitant to expose his ironclads to the island’s heavy guns after suffering severe damage at the previous forts. Going downriver with the current was much easier than coming back up. The cumbersome vessels could be disabled, captured, and turned against friendly river cities.

Along with the ironclads and wooden gunboats, Foote brought eleven rafts mounting 13-inch mortars. Mortar gunboats had been proposed to President Lincoln in November 1861 by Lieutenant (and future admiral) David D. Porter as a means to overcome shore fortifications, specifically those guarding the river approaches to New Orleans. It had been unthinkable in previous centuries for wood and canvas men-of-war, dependent on wind and armed with smaller guns, to take on heavy fixed shore batteries behind stout walls. At the 1855 Battle of Kinburn in the Crimea, British and French ironclad floating batteries for the first time prevailed against Russian forts, but Americans had no such experience.

Ever enthused by new ideas, Lincoln pushed the plan. The mortars, firing enormous shells in high arcs from more than two miles distant, should neutralize the bastions and allow Farragut’s squadron to pass safely—an expectation that would not be realized. They similarly would be useful upriver. The president ordered two mortar flotillas constructed, one for each thrust, but met resistance at every turn.

A skeptical Secretary Welles put priority on constructing sea-going mortar boats for the New Orleans expedition and neglected those building on the Ohio River. General Halleck was not interested, particularly without additional appropriations, and Foote, based in Cairo, Illinois, did not think much of the queer little vessels. When not much happened, the frustrated commander-in-chief again became hands-on to overcome interservice barriers and bureaucratic lethargy. He required daily telegraphic reports and issued command directives until the mortar boats were completed and deployed, north and south.

Foote halted his flotilla above Island No. 10 on March 15, 1862 and began a furious three-week mortar bombardment from long range that achieved no significant results against sand and log ramparts. An impatient General Pope cut a canal across the isthmus separating the horseshoes, deep enough for several troop transports—but not for ironclads—to bypass the island and join him in New Madrid. He asked the flag officer to send a gunboat past the batteries and cover the army’s crossing to the Tennessee side below and behind the Rebel positions.

Captain Henry Walke of the USS Carondelet persuaded the reluctant Foote that he could make it. The ironclad was covered with rope, chain, and whatever loose material lay at hand. A barge filled with coal and hay was lashed to her side. Her steam exhaust was diverted from the smokestacks out the side of the casemate to muffle sound. On the moonless night of April 4 under a raging thunderstorm, Carondelet slithered downstream unscathed and almost undetected. Another ironclad followed. Covered by the ironclads’ guns, Pope’s army crossed the river, isolated the Rebel garrison, and forced their surrender on April 8 just as the Battle of Shiloh was raging and McClellan was bogged down on the Peninsula. The river now was open as far as Memphis.

Carondelet’s dramatic passage introduced a new naval tactic: driving vulnerable war vessels through narrow channels past heavily armed fortifications. Steam, iron, and bigger naval guns had evened the odds between ship and shore. These methods would be repeated on a larger scale three weeks later, April 24, as Farragut’s deep-water warships of the Gulf Blockading Squadron blasted by Forts Jackson and St. Philip to take New Orleans. Forts at Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Mobile Bay later received similar naval attention.

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1862, hundreds of Memphis citizens assembled high on the city bluffs to observe a battle. But there were no surging ranks of blue and gray in the valley below, just the Big Muddy rolling broad and inexorable toward the sea. This would be a purely naval contest in the heart of the continent in which two separate Union commands—the Western Gunboat Flotilla and the ad-hoc United States Ram Fleet—confronted the equally strange Confederate River Defense Fleet. The most modern technology engaged the most ancient weapons, and civilians with no military experience commanded warships in combat.

Looking to their right, the anxious watchers saw five squat, black shapes emerging from the mist upriver, belching smoke from their stacks. Four of them were the Pook turtles USS Louisville, Carondelet, St. Louis, and Cairo. The fifth was the converted ironclad USS Benton. Flag Officer Charles H. Davis had relieved Foote as Union flotilla commander in May. Like Foote, Davis worried that his clumsy and underpowered floating batteries might descend the river into fierce opposition only to be trapped, damaged, possibly captured. Because the ironclads had more power going ahead than astern—and thus better odds of withdrawing upriver if needed—he turned them around, formed them into line abreast, and backed downriver to engage with rear-facing guns.

An even more unique Union squadron closely followed the ironclads. The United States Ram Fleet was a wholly civilian, volunteer navy commanded by a family of rivermen operating improvised vessels employing a weapon not seen since Mediterranean rowing galleys disappeared three centuries before. Noted civil engineer and riverman Charles Ellet, Jr. was convinced that—with steam power—ramming was again a viable naval tactic. Ellet persuaded Secretary of War Stanton to appoint him a colonel of engineers with authority to build his own flotilla.

Ellet converted several powerful river towboats, heavily reinforcing their hulls for slicing into enemy hulls. Boilers, engines, and upper works were lightly protected with wood and cotton bales. Other than small arms, they had no guns. Colonel Ellet reported directly to the secretary of war, operating independently of department commander General Halleck, and only voluntarily cooperating with local commanders. The colonel had engaged in no tactical planning with Flag Officer Davis as they descended the Mississippi beyond a general understanding to assist.

Memphis citizens cheered as eight vessels of their River Defense Fleet steamed out to defend the city against five ironclads and four rams. Numbers were about equal, but not fighting quality. Confederates had seized a motley collection of wooden passenger, cargo, and tow boats for the defense of New Orleans, converting them to rams with heavily reinforced prows and arming them with one or two light-caliber guns.

Carpenters fitted additional protection around engines and interior spaces consisting of double, heavy-timber bulkheads overlaid with railroad iron. The 22-inch gap between bulkheads was packed with cotton, so they became known as cottonclads. Like Ellet’s group, the Rebel boats were captained and crewed by civilian rivermen, nominally under army command, but each operating independently and with no command structure or procedures.

Six River Defense Fleet rams had been pushed aside easily by Farragut’s squadron at New Orleans in April. The other eight were sent up to Memphis to defend the northern flank under command of riverboat captain James E. Montgomery. On May 10, five of them surprised and rammed the city-class ironclads Cincinnati and Mound City at Plum Point Bend above Memphis. Both Union vessels were grounded and sunk in shallow water but soon were raised and placed back in service.

On this morning of June 6, Louisville, Carondelet, St. Louis, Cairo, and Benton slid downriver backwards—spinning their great paddlewheels more to hold against the current than to advance—and opened an inconclusive, long-range gunnery duel with the Rebel rams. The impatient Col. Ellet, without instructions or notice, opened his steam throttles, charged through the ironclad line in his Queen of the West, and struck the first Confederate vessel encountered, sinking it immediately, only to be rammed himself by another.

The other Ellet rams followed while the ironclads closed to deadly range. A raging melee erupted with no coordination on either side. The Rebel squadron, unarmored and outgunned, was destroyed marking the near eradication of Confederate naval presence on the river. Colonel Ellet received a mortal wound, the only Union casualty. Command of the ram fleet passed to his younger brother, Alfred Washington Ellet, and to his son, Charles Rivers Ellet. The Battle of Memphis was the only solely naval engagement or “fleet action” on the rivers. It also was the last in which ramming was a primary tactic, and the last time civilians commanded ships in combat. The loss of the Confederacy’s fifth-largest city and key industrial center opened the Mississippi all the way to Vicksburg and opened West Tennessee to Union occupation.

Following the battle, a major reorganization transferred the Western Gunboat Flotilla from the War Department to the Navy Department and re-designated it the Mississippi River Squadron equal in stature to coast blockading squadrons, the navy’s senior command unit. Ellet’s ram fleet was renamed the Mississippi Marine Brigade (no connection to U.S. Marines) reporting to the squadron commander. The rams would be employed primarily for amphibious raiding and support tasks, but never again in the type of naval combat for which they were designed. Farragut was appointed the first United States admiral and ordered to bring his gulf squadron from New Orleans on up the Mississippi as far as Vicksburg, where he ran the gauntlet of guns on the bluffs to join up with Davis and the river squadron.

On July 15, 1862, the hastily constructed Confederate river ironclad CSS Arkansas steamed out of the Yazoo River into the Mississippi and with guns blazing charged right through the astonished Union fleet into Vicksburg while twenty thousand spectators cheered from the city heights. Exultant locals greeted the battered vessel and its crew, dazed, power-blackened, and streaked with blood and sweat. “Blood and brains bespattered everything,” noted one observer, “whilst arms, legs, and several headless trunks were strewn about.” In August, the crippled Arkansas supported a Confederate attempt to retake Baton Rouge. With her engines failing and under murderous fire from Union gunboats, she was abandoned and destroyed.[6]

Meanwhile, the largest U.S. Navy armada ever assembled on a river bombarded the fortifications but could not take the Gibraltar of the West, as Vicksburg was called, without the army. Panicked by the Rebel surprise at Shiloh, General Halleck ordered Pope to abandon the river campaign and join Grant at Pittsburg Landing for an advance on Corinth, Mississippi. Thus, was a crucial strategic opportunity lost to capture Vicksburg in 1862. Falling water levels and low coal supplies compelled Farragut to withdraw his deep-draft vessels from the river to the severe disappointment of President Lincoln. It would be another year before the city succumbed to the greatest joint army-navy campaign of the conflict.

The president called General Halleck to Washington to become general-in-chief leaving Major. General Grant in command of the Army of Tennessee. In October, David D. Porter, now a rear admiral himself, succeeded Davis in command of the Mississippi River Squadron. Typically, suspicious of soldiers, the outgoing Porter was disarmed by Grant’s unpretentious nature. The admiral and the general made another powerful team, melding strategic flexibility of maritime power with hard and smart fighting on land. But it was a learning process. In late December, Grant sent W. T. Sherman downriver with a major amphibious force landing at Chickasaw Bayou northwest of Vicksburg, only to be repulsed with heavy casualties. Porter’s attempt to send gunboats up the Yazoo River and outflank the Confederate army facing Grant also failed, losing the ironclad USS Cairo[7] to a Rebel torpedo, the first ship to be sunk by an explosive device remotely detonated by hand.

A more successful army-navy operation occurred in early January when two Union corps under Major General John Alexander McClernand ascended the Arkansas River north of Vicksburg. Transports landed troops near Confederate Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post. The fort sat on a bluff twenty-five feet above the river defending Little Rock and threatening Union movement on the Mississippi. Porter's ironclads Baron DeKalb, Louisville, and Cincinnati pounded the fort at a range of 400 yards while blue ranks advanced. The outnumbered garrison surrendered. But McClernand had acted without notifying Grant and the operation made no contribution to the Vicksburg campaign.

During the winter and spring of 1862/63, Grant conducted a series of intense but fruitless operations to outflank the city from north and east by digging canals, blowing up levees, flooding the Mississippi Delta, and pushing ironclads, gunboats, and troop transports through tiny, choked and sluggish channels and swamps. The general’s memoirs stated that these efforts were intended primarily to keep his troops busy during the flooded and disease-ridden winter and that he had no expectation of success, but this claim is somewhat contradicted by his contemporary correspondence.

Grant’s final option was to march the army through the swamps down the west bank of the Mississippi, cross south of and get behind Vicksburg. Admiral Porter would have to sneak his gunboats and transports downriver past the Rebel batteries to support the army crossing. He assumed this would be a one-way, one-time run; it would be suicidal to try a transit back upriver against the current.

On April 16, 1863, a clear night with no moon, seven gunboats and three transports loaded with stores got underway. Despite efforts to minimize lights and noise, the vessels were detected; the bluffs exploded with massive artillery fire. Confederates bonfires along the banks illuminated the scene. The Union column hugged the east bank to get under the line of fire, so close they could hear rebel gunners shouting orders while shells zinged overhead. On April 22, six more boats loaded with supplies made the run. Only two transports were lost, thirteen men wounded, and none killed.

Under cover of naval artillery, Grant ferried his army across the river, surrounded, and laid siege to Vicksburg, which surrendered on July 4. It was one of the most brilliant campaigns of the war, at least as important as the simultaneous victory at Gettysburg. The Mississippi River Squadron transported the army, closed the river, and provided continuous heavy shore bombardment. The fall of Port Hudson, Louisiana, the last Rebel stronghold on the great river, soon followed.

One other campaign made a dramatic postscript to the river war. In the spring of 1864, President Lincoln sent Major General Nathaniel Prentice Banks and approximately 30,000 troops with Porter’s squadron up the Red River to invade northwest Louisiana and east Texas. Poor planning and mismanagement by Banks led to complete failure and near disaster. The river squadron was only saved by heroic efforts of army engineers to dam falling river waters and by gunboat captains to push back downriver.

“The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea,”[8] wrote Abraham Lincoln. Having lost the Tennessee line with Forts Henry and Donelson, Confederates gambled that their Mississippi River bastions would hold while they concentrated for all-out attack at Pittsburg landing. Grant survived and the dominoes fell—Island No. 10, Memphis, Vicksburg, Port Hudson—to army-navy teamwork. The brown-water navy of the Mississippi River Squadron kept busy for two additional years fighting Rebel guerrillas, suppressing enemy trade, and protecting friendly commerce.

- [1] The Anaconda Plan was General Scott’s proposed strategy submitted to President Lincoln in May 1861. The plan emphasized the blockade of Southern ports and called for an advance down the Mississippi River to cut the Confederacy in two. The name was initially applied by detractors like Major General George Brinton McClellan, who likened it to an anaconda suffocating its victim. They thought the concept too passive, indirect, and slow, advocating instead an immediate overland campaign directed primarily at the Confederate capital of Richmond. The essentials of the Anaconda Plan as implemented by Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant were validated by events.

- [2] Major General William T. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 10, 1862, University of North Dakota, Sherman Family Papers.

- [3] Welles to Rogers, May 16, 1861, Welles to Rogers, June 12, 1861 in United States Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922), Series I, volume 22, part 2 p. 280, 284-5.

- [4] The title flag officer referred not to rank but to position: a senior officer assigned to command a group of war vessels. Foote’s rank was navy captain, equivalent to army colonel. The U.S. navy in early 1862 had no general officer equivalents because it had never deployed large fleets. Admiral ranks would be established later in the year to be on equal standing with army counterparts.

- [5] When Grant received a request for terms from Confederate Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner Sr., the fort's commanding officer, he replied that "no terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." Newspapers reporting the victory noted that Grant's first two initials, "U.S.," stood for "Unconditional Surrender" and that became his nickname.

- [6] Chester G. Hearn, Naval Battles of the Civil War (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2000), 130.

- [7] The remains of Cairo can be viewed at Vicksburg National Military Park with a museum of its weapons and naval stores.

- [8] Abraham Lincoln to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863, in Merwin Roe, ed., Speeches and Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1832-1865 (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co, 1907), 222.

If you can read only one book:

Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. The Civil War on the Mississippi. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016.

Books:

Canney, Donald L. Lincoln’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861-65. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998.

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Gosnell, Harpur Allen. Guns on the Western Waters: The Story of River Gunboats in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1949.

Groom, Winston. Vicksburg, 1863. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

McPherson, James M. War on the Waters: the Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012, especially chap. 4.

Murray, Williamson and Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh. A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016, chap. 5.

Smith, Myron J. The Timberclads in the Civil War: The Lexington, Conestoga, and Tyler on the Western Waters. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2008.

———. Tinclads in the Civil War: Union Light-Draught Gunboat Operations on Western Waters, 1862-1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2010.

———. The CSS Arkansas: A Confederate Ironclad on Western Waters. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2011.

Still, Jr., William N., ed. The Confederate Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1861-65. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997.

Symonds, Craig L. Lincoln and His Admirals: Abraham Lincoln, the U.S. Navy, and the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Taaffe, Stephen R. Commanding Lincoln’s Navy: Union Naval Leadership During the Civil War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009, chap 3.

Organizations:

USS Cairo Gunboat and Museum

The USS Cairo was sunk at Vicksburg in 1862. Starting in 1972 the Cairo was raised and is now restored and open to the public. The museum contains displays of artifacts recovered from the Cairo. The ironclad and museum are located at 3201 Clay Street, Vicksburg, MS 39183. 601 636 0583 and are open from 8:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. Monday to Saturday.

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Civil War Navy—The Magazine

Civil War Navy—The Magazine, published quarterly, was launched in 2012 to explore and describe in detail the naval history of the conflict and more fully underpin its military role and importance.