The Battle of First Kernstown

by Phillip S. Greenwalt

Winchester Virginia was the epicenter of trade and transportation for the lower Shenandoah Valley and its road network provided a route for Confederate attack into Maryland or against Washington D.C. In the spring of 1862 General Stonewall Jackson’s small Confederate army was charged with keeping much larger union forces under General Nathanial Banks tied up in the Valley and unavailable for reinforcement of General George B. McClellan’s advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond. On March 22, 1862 Banks’ forces were gathered near the village of Kernstown and were being harassed by a small force of Confederate cavalry and infantry under Colonel Turner Ashby. Probing by union forces did not penetrate Ashby’s screen and union commanders concluded that they faced only cavalry. Fighting continued on Sunday March 23 as Jackson marched his force towards Kernstown, under the assumption that he faced a small Union command that he outnumbered. On reaching Kernstown Jackson reinforced Ashby who was outnumbered by the Federal forces he faced and then began a movement west. Union forces were on high ground to Jackson’s front on Pritchard’s Hill. Jackson planned to outflank the Federals by taking Sandy Ridge to their west. As the fighting developed the commanders on both sides realized they were dealing with larger forces than they had previously believed. While the Confederates advanced to try to outflank the Union right, a union brigade advanced to outflank the Confederate left. The two forces met at a stone wall running perpendicular to Sandy Ridge, but the Confederates got there first and repelled the Federals. Both sides fed reinforcements into the fighting on Sandy Ridge. As the fighting continued into the early evening the Confederates began to run low on ammunition and General Richard Garnett directing the fighting on Sandy Ridge ordered the Confederates to begin withdrawing. Jackson was overseeing the fighting elsewhere and did not know that his subordinate had ordered a withdrawal. His attempts to stem the tide of retreating Confederates failed and Jackson’s force of 3,500 men left the field to the 8,500 federals, a union victory which saw 600 Union casualties and 700 Confederate casualties. After the battle Union forces in the Valley consolidated around Kernstown and only one brigade left the Valley to join McClellan. Though defeated, Jackson earned plaudits from the Confederate Congress for having succeeded in carrying out his strategic objective and at First Kernstown set the table for the most daring and successful campaign of his entire career, The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862.

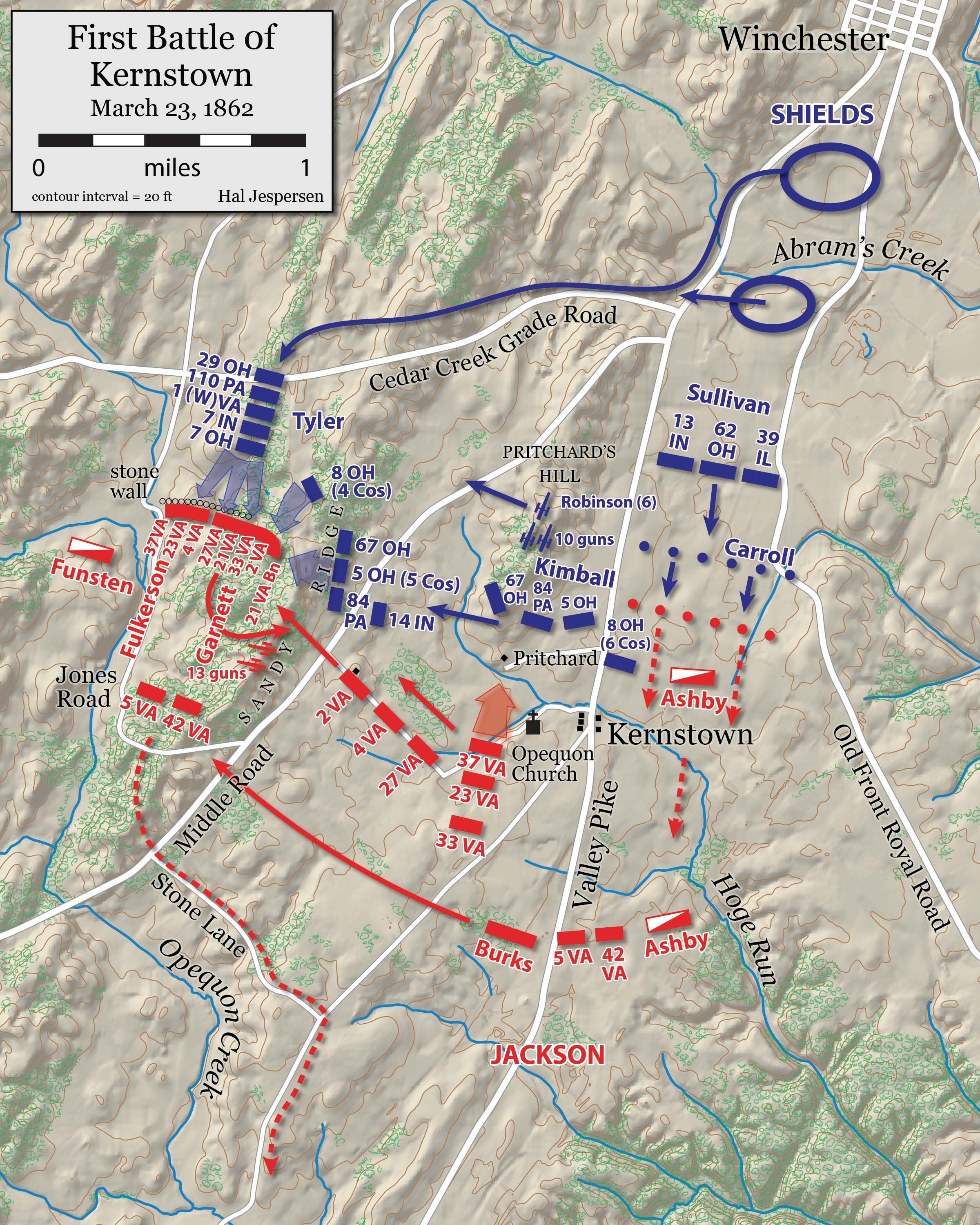

Map of the Battle of First Kernstown

Map Courtesy of Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com

Winchester, Virginia, the epicenter of trade and transportation for the lower Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Situated in northern Virginia, Winchester sat astride the Valley Turnpike, the only macadamized road in the region. The town was barely over 30 miles south of the Potomac River and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, another logistical trade route running down the north side of that waterway. Emptying into the town was the Berryville Turnpike, which took travelers across the Blue Ridge Mountains and into the northeast Virginia region.[1]

With the outbreak of hostilities in 1861, Winchester was crucial to the Northern cause, as the town sat astride a road network that could lead to the United States capital in Washington D.C. and if the region could be defended, block any aggressive Confederate movement north. For the South, Winchester was a linchpin to a successful jaunt across the Potomac into the state of Maryland and further invasion north.

For both sides, Winchester was the key to the lower Shenandoah Valley and the outlet for any supplies moving down the Valley of Virginia the nickname given to the Shenandoah Valley. In a unique geographical connotation, since the rivers ran southeast to northwest, travelers headed north would be moving down the valley and vice versa.

All these attributes were part of the consideration of Confederate Major General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, in charge of the Confederate department comprising the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1862. The military advisor to the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, the soon-to-be famous army leader, General Robert E. Lee had stressed the importance to Jackson of keeping Union forces, under Major General Nathanael Prentice Banks tied up in the valley and thus unable to reinforce Northern forces on the eastern side of Virginia.

Although outnumbered by Banks, Jackson saw an opportunity in late March to strike at the Northern invaders as they drew back up the valley toward Winchester. Banks was slowly moving troops through Winchester and out the thoroughfares to the east to do exactly what Lee feared; reinforce the army under Major General George Brinton McClellan, then planning an advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

Serving under Banks was a fiery Irishman, Brigadier General James Shields, who would grapple with Jackson throughout the upcoming Valley Campaign of 1862. His audacity as a division commander on March 23, would hand Jackson his only defeat in that spring and summer. Yet, in defeat, Jackson would win more than Shields. What unfolded next was the Battle of Kernstown, the first of two engagements in the same vicinity, and the fallout from this engagement in the campaigning season of 1862.[2]

“Stonewall” Jackson abhorred fighting on a Sunday. The day, March 22, 1862, had dawned “cloudy but not cold or stormy” for Jackson’s army, encamped at Strasburg, Virginia. Four companies, from the 2nd Virginia Infantry and a sole company from the 27th Virginia Infantry, had rushed off that morning to support Colonel Turner Ashby, who had taken cavalry back toward Winchester to discover Union strength and intentions. The rest of the command had time to cook breakfast over the campfires and fall in for a march down the Shenandoah Valley, via the Valley Turnpike, toward Winchester, Virginia approximately 20 miles to the north.[3]

Thirteen miles to the north of Jackson’s overnight encampment, the intrepid Colonel Turner Ashby, in charge of all Confederate cavalry associated with Jackson’s command, was tangled with the Union division under Brigadier James Shields. However, the previous day, March 22nd, Shield’s had been wounded by a Confederate artillery shell, so Colonel Nathan Kimball had assumed command.[4]

Kimball, who hailed from Indiana, awoke that morning assuming that the pesky Ashby and his Confederate cavalry were the only Southern force in the area. Little did he know that 3,600 Confederate infantry were on their way toward the Union position.

The Union forces were congregated near the village of Kernstown, named for Adam Kern Sr. who in 1766 migrated to Frederick County, Virginia from York County, Pennsylvania. Kern would settle approximately three miles down what was called the “Great Wagon Road” which would be macadamized in the 19th century and become the Valley Turnpike. His son, Adam Kern Jr. would be the Kern that gave the town its name. [5]

Now, three Union brigades, comprising 7,000 Union soldiers, five artillery batteries and 750 cavalrymen, were arrayed as follows. To the east of the Valley Turnpike, stood the brigade of Colonel Jeremiah Cutler Sullivan, who also hailed from Indiana, and whose command was labeled the Second Brigade. Immediately behind Sullivan’s command was Kimball’s Brigade, the First Brigade. Lastly, Colonel Erastus Bernard Tyler, a New Yorker, had his “Third Brigade” in reserve near the southern environs of Winchester.[6]

Shields, who was nursing his wound back in Winchester, had sent his directives to Kimball that morning. The Indianan was “to drive or capture the enemy” as the Confederates in front of the Union division were perceived to be nothing more than Ashby’s observation force. At 9:00 a.m. that morning, Colonel John Sanford Mason of the 4th Ohio Infantry, was ordered by Shields to advance and reconnoiter what was in front of the Union forces. Within an hour, Mason had returned with the cheery news that there was nothing but Confederate cavalry. After this reconnaissance, the Union high command, including Major General Nathaniel Prentice Banks, in charge of the Union V Corps, concluded “that Jackson could not be tempted to hazard” an engagement and thus Banks’ other two divisions could continue their march to the east, through the Blue Ridge Mountains to rendezvous with Major General Irwin McDowell and take part in the ensuing campaign being conducted by General George McClellan.[7]

Yet, the Union command was presumptuous. First, Mason’s reconnaissance had not succeeded, but failed, in that he did not penetrate Ashby’s screen of cavalry. What lay behind the Confederate cavalry videttes would soon become apparent to the Federals.

If all seemed quiet to Mason, Shields, and even Banks, that was certainly not the case on the Valley Turnpike to the south. Jackson’s foot cavalry, as his infantry would come to be known because of their ability to march long distances quickly was rapidly approaching. Before their arrival, Ashby would continue to harass the Federal soldiers. Like his counterpart, Jackson was also under a false assumption; he believed that Kimball’s force was small and that his Confederate forces would outnumber his adversary.

With the addition of the five infantry companies, Ashby had continued his protracted skirmishing with the Union soldiers for another day. After spending the night between Batesville and Newtown, Ashby’s forces retraced the two miles back toward Kernstown on the morning of March 23rd. A quarter mile from Hoge’s Run, a small meandering tributary of Opequon Creek, one of many that crisscrossed this section of the Shenandoah Valley, Ashby set up his horse-artillery, under the command of Captain Robert P. Chew. Captain Chew had the crew begin preparations to fire, including elevating the barrel lifting the trajectory of the British made, imported Blakeley rifle, the longer-range weapon in the battery. While this was happening, members of the 7th Virginia Cavalry began moving into Kernstown.[8]

With the five infantry companies, Ashby began the fighting on the Sabbath. However, Ashby soon noticed that his small infantry force and accompanying cavalry were severely outnumbered.

Marching down the Valley Turnpike, banners snapping slightly in the spring breeze, Jackson’s main column arrived in the vicinity of Kernstown in the early afternoon. At the small town of Bartonsville, the Confederate column would take a momentary pause, filing off the turnpike into Barton’s Woods. Initially, the Confederate commander thought to rest the men for the remainder of the day, reconnoiter the Union line prepare his battle plan, and strike the next day. Yet, these designs changed after Jackson rode amongst the troops and noticed their gaiety, even though his of foot cavalry had marched over 25 miles in the last 36-hours. In addition, the Federals current position on top of an incline afforded the men in blue the ability to gaze down on the Confederate formations as Jackson made the crucial decision to attack.[9]

He eschewed his own mantra of not fighting on the Sabbath to follow his other doctrine: answering when duty called. Now that he had decided to fight, Jackson quickly developed his attack plan. Remarkably, Jackson made his battle plan without consulting Ashby, who had been fighting in the surrounding fields and would have a working grasp of the tactical situation. By 1:30 p.m. Jackson implemented his plan of attack.

To the left or west of his men, Jackson’s tactical eye saw the high ground known as Sandy Ridge, situated to the west of the Valley Turnpike. If he could gain control of that ridge, which ran parallel to the pike, he had the possibility to outflank the Union line situated on the opposite height of Pritchard’s Hill.

Jackson ordered Colonel Jesse Spinner Burks’ Brigade, which was resting along the Turnpike to support Ashby while the other two brigades, under Colonel Samuel Vance Fulkerson and the Stonewall Brigade under Brigadier General Richard Brooke Garnett advanced down the Valley Turnpike. The advance led them toward Opequon Church which was built in the 18th century and became a symbol of early European settlement in the Shenandoah Valley. When Confederate forces neared the structure, only a quarter mile approximately from where the advance began, Federal soldiers, both infantry and cavalry could be seen. Jackson responded by ordering Captain Joseph Carpenter to deploy the two pieces of artillery he currently had with him and disperse the enemy. This he did in quick order.[10]

After clearing the church and the small community that sprawled from the place of worship, the Confederate column filed to the left, taking advantage of a small country lane. In the vanguard was the 37th Virginia Infantry, raised primarily from Washington County, Virginia on the North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia border. Following close behind the 37th Virginia was the 23rd Virginia Infantry, which hailed from the capital of Virginia and surrounding counties. After leaving the country lane, the units cleared one of the many woodlots that would traverse the battlefield. These two regiments, and part of Colonel Fulkerson’s Brigade came upon an open and undefended field. Fulkerson halted the forward movement and sent back an orderly for further orders. Shortly thereafter the messenger returned with a directive to form into battle formation, proceed across the open field that was to their right-front and silence a Federal battery that was lobbing shells from a position in their front, to the west of Kernstown. Other Confederate infantry would be in support of the operation, including four of the five regiments that comprised the Stonewall Brigade.[11]

Fulkerson moved to carry out the orders and his men dismantled a wooden plank fence and proceeded into the open field toward the Federal battery. As Fulkerson’s men began their charge into the open, the first unit of Garnett’s command, the 33rd Virginia, commenced their attack. On the opposite side of the field and on top of Pritchard’s Hill, the Union defense waited the onslaught. The spectacle of the oncoming Confederates initially unnerved some of the artillerists of Lieutenant Colonel Philip Daum’s 1st Ohio Artillery. The Union officer forcibly returned the green artillerists to their posts and threatened any soldiers who thought about shirking their duty again by with decapitation by his sword. Besides the Ohioans manning the guns, their fellow Buckeyes in the infantry; the 5th, 8th and 67th were nearby to provide support. Adding to their firepower was the 87th Pennsylvania.[12]

A tremendous, small arms fire met the Virginians as the men charged across the field. Under this withering fire, Fulkerson’s command moved toward another wooded area. Yet, the objective of the tree line was unreachable and instead, the Confederates veered more to the left, which placed them into more of the open meadow.

Remembering this initial advance, Fulkerson equated the Union firepower to such an extent “that well might have made veterans quail.” So, far, Fulkerson’s Third Brigade had advanced one half-mile toward the Union line. Regrouping and understanding that he could not take the Union guns perched on Pritchard’s Hill, the Virginian settled on the idea of flanking the Union position.[13]

With his momentum stalled, the Southern line “was thus wedged shaped.” On the right was the three batteries of Captains Carpenter, William McLaughlin, and James Waters. On the opposite side was Fulkerson’s Brigade, and in the middle were two regiments from Burks’ Brigade and the entire Stonewall Brigade under Garnett.[14]

During this temporary lull, Jackson’s aide Alexander “Sandie” Pendleton returned from reconnoitering the Union position and brought startling news. The enemy forces occupied “a high position in front of our batteries and very exposed.” Not only were the Federal soldiers in a position of strength but Pendleton estimated that the entire force was around 10,000.[15]

Ashby had estimated that there was only a small rearguard, and the area was lightly defended. Jackson now realized that this erroneous information hazarded his entire force. Yet, by mid-afternoon on Sunday, Jackson showed the glimpse of his mental fortitude and demeanor in battle that would characterize the ensuing campaign. His response to Pendleton was simple, direct, and showed no sign of quitting the field.

Jackson stated, “Say nothing about it, we are in for it.” Later Pendleton would draft a letter to his mother and added three words to Jackson’s response, “and we were.”[16]

Meanwhile, the Union commander had also realized he was grappling with more than the pesky Ashby and some detached infantry. Regardless of what enemy forces were in his front, the Indianan realized he had a great defensive position with a view of Southern dispositions, and he was content to react to the Confederates’ moves.

Shields, who admitted that any specific movements would, out of necessity, must be made by Kimball who was on the field, continued to send what support he could. During the break in the fighting, the 13th Indiana and 39th Illinois, both of the “Second Brigade” under Sullivan were to reinforce Kimball.[17]

The second installment of fighting erupted soon thereafter, when the 27th Virginia supported by the 21st Virginia, began a seesaw of offensive charge and defending Union countercharges, within view of Jackson.

As the Confederates sought out the right flank of the Union forces, Colonel Kimball was calling in the last of the three brigades. Colonel Erastus B Tyler’s command was ordered to march from the location of the Toll House, south of Milltown. Tyler. Using the Cedar Creek Grade Road to cut perpendicular toward Sandy Ridge, Tyler’s bluecoats came into the woods in column formation.[18]

As Tyler’s advanced the fray, immediately in front of the command was one solitary Confederate regiment that had ensconced itself behind a stone wall. This was the 27th Virginia Infantry. Caught up in the moment, Tyler did not take the time to shake out a battle line, instead rising in his stirrups as he reined his horse in at the front of the column. With a hearty yell of “Charge Bayonets” the Union brigade lurched forward.[19]

Into the maelstrom of Confederate bullets charged the bluecoats. Not content on just slinging lead at the enemy, the Southerners spewed taunts at their adversaries as well. To mask the weak numbers of the 27th Virginia, which numbered close to 200 muskets, Colonel John Echols spread his line out. Behind his right flank, Captain Carpenter’s artillery sprang into action.

As the bluecoats neared a sharp depression the leading regiments, the 7th Ohio and 7th Indiana went to ground; lying down to present a smaller target. One of the Buckeyes would remember “a most terrific roar of musketry” emanating from the rebels. Brief moments passed until line officers and sergeants got the lead regiments of Tyler’s command moving forward again. The charge was coming unraveled already, as the whine of bullets seared past the Indianans and Ohioans and unnerved the 110th Pennsylvania farther back in the column. As another regimental officer described the Keystone State natives breaking “and scampering like sheep at the first fire.”[20]

Some pandemonium can be attributed to the untimely exit of over 300 Pennsylvanians farther back in the attack column coupled with the brigade commander busily trying to remedy his mistake of formation at the front. The timing though, could not have been worse for Tyler as some of his command was less than one-hundred yards from the Confederate battle line. With the din of battle raging not all of Tyler’s command heard his commands and so the contour of the Union formation was mixed-up.

On the Confederate side, the tall and imposing physique of Colonel Echols had a calming influence on his outnumbered command. Expending ammunition and starting to feel the effect of the more numerous enemy, Echol’s command was reinforced by the 21st Virginia, which extended the Confederate line further east, with the right most companies refusing the flank to protect the precarious end of the formation. At this time, Echols was wounded, when a bullet slammed into his left shoulder and cracked the bone of his arm. He would have to leave the field, turning command over to the fiery Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Jackson Grigsby. The loss of their beloved commander hurt the morale of the 27th Virginia who started to back away from their defensive position.[21]

As Colonel John M. Patton’s 21st Virginia deployed on the right of the 27th Virginia, Union General Tyler began to look toward his own right flank to turn the Confederate position. He called upon Colonel Joseph Thoburn and his 1st West Virginia. Leaving the wood line which Tyler’s Brigade had advanced through, the Western Virginians rushed across the open terrain and to another of the many stonewalls that dotted the lower Shenandoah Valley.

This bulwark extended in a perpendicular direction from the stonewall where the Virginians were. Attaining this stone breastwork would turn the Confederates out of their line, with the potential to flank the enemy, and win the contest. All Thoburn’s men had to do was reach the undefended wall and the day’s action could be decided.

With the bluecoats tantalizingly close to their destination, seemingly out of nowhere appeared two Confederate regiments, the 23rd and 37th Virginia regiments from Fulkerson’s Brigade. Constantly in motion and having already been bloodied in earlier attacks Fulkerson had made the timely decision to place his two units in some woods on Sandy Ridge, concealing them in supporting distance of both the 21st and 27th Virginia Infantries. While this placement put them within range of the 7th Ohio, the blue-coated infantry fire did not cause any casualties.

From this slightly elevated position though, the two Confederate regiments could react to any Union movement in the fields below and respond in a timely manner. The Virginians proved a little more fleet of foot arriving at the stonewall destination moments before the enemy. Using the top to rest their muskets, Fulkerson’s command unleased a withering fire on the blue coats, marooned in the open, a mere forty yards away.

One Confederate, with a touch of honesty and brevity, would later write; “I do not know if I ever hurt anybody during the war or not. If I did, it was probably on this occasion.”[22]

Leading from the front, Thoburn was struck by three bullets, two puncturing his garments and the last shattered his arm. Still showing poise, the Irishman tried directing his command from a sitting pose. A few of Thoburn’s men did make it over the wall but were beaten back by the 37th Virginia who was directed to clear the enemy from behind the stonewall. The bluecoats were pushed back and with their comrades headed toward the woods on the far side of the field they had just charged over.[23]

This action, which to some participants must have felt like hours, had lasted approximately ten minutes, from the time Tyler’s column charged forward to the 37th Virginia clearing Thoburn’s bluecoats from behind the stonewall.

As the clock ticked past 4:00 p.m. the Confederate line comprising the left flank of Jackson’s army stood as follows; Fulkerson’s position on the left, then a gap on the right of the 23rd Virginia Infantry. After the gap was the 27th and 21st Virginia regiments which had a position on the elevation of Sandy Ridge and took advantage of a stonewall running there for protection. As the fighting raged, Garnett had appeared on Sandy Ridge with the 33rd Virginia, had been notified by Grigsby where one of his regiments, the 27th Virginia, had been pulled to, and was taking stock of the situation when the fighting from Taylor’s assault had reached a crescendo. Also, from this vantage point, Garnett could hear, if not see, the action to the east of the Valley Turnpike, between Sullivan’s Unionists and Ashby’s Confederate horse soldiers that was still raging hot.

Garnett then ordered the 33rd Virginia to remain behind and across an open field from where the 21st and 27th Virginia fought back Tyler’s advance. He was unsure if the twin Virginia regiments could fend off the attacking Federals and was unaware in the din and smoke of the enveloping battle when Fulkerson had launched his successful advance to stymie Thoburn’s command.

With the immediate action over by 4:00 p.m. Garnett moved the 33rd Virginia onto the right flank of the 21st Virginia by 4:15 p.m. As this happened, the 4th Virginia, approximately 250 rifles, which had traded shots with the enemy from the safety of the trees near the ridge, soon braved the desultory fire coming from Tyler’s retreating men, and followed Garnett’s directive to approach the stonewall and fill the gap. The 4th Virginia filed onto the spur of ground to the left of the 27th Virginia and extended to the right of the 23rd Virginia.[24]

Now, facing off against each other were the approximately 1,700 Union soldiers comprising Tyler’s Brigade and the 1,200 Confederates from Fulkerson’s and Garnett’s Brigades. In the late afternoon, the engagement in this sector would become a disorganized mess. Musketry was drowned out by the competing artillery and men were killed and wounded indiscriminately. Commands became intermixed on both sides, partly due to how the regiments arrived at the stonewall and partly due to the nature of Jackson’s command that day. The Confederate commander had been pulling individual regiments for various tasks as he came upon them, disregarding brigade structure in the process. Confusion could sum up both sides around the base of Sandy Ridge and the ubiquitous stonewall.

Slightly before 5:00 p.m. the last Confederate reinforcements arrived in the form of the 2nd Virginia, numbering 310 men when it entered the fracas. One unit interspersed was the Irish Battalion belonging to Burks’s Brigade. These were the last reinforcements to arrive in this sector, bringing the total number of Confederates to 1,700.

Now it was time for the bluecoats to reinforce Tyler. Luckily for Kimball, Tyler’s division commander, had the foresight in the early afternoon to send a messenger racing on horseback to recall a brigade from Brigadier General Alpheus William’s Division then enroute east across the Blue Ridge Mountains. Williams had kept a brigade west of the Shenandoah River after a bridge broke due to the strain of the passing division and accompanying wagons.[25]

While reinforcements slowly turned back toward Winchester, Kimball consolidated his control, improved the relay of information, and received reports coming in from combatants of the Sandy Ridge fighting.

The firing was intense, the major of the 2nd Virginia, Frank Jones reported. “The most terrific fire of musketry that can be imagined commenced and continued for one hour & 35 minutes…” Regiments from Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio battled the Virginians as the day wore on. Jackson busied himself by pulling any reserve regiments he could toward his left flank.[26]

These reinforcements comprised the 5th, 42nd, and 48th Virginia regiments. The 5th Virginia took up position on the extreme right of the stonewall with the right flank of the regiment near the Valley Turnpike. The action in this sector would remain hot for the next two hours due to Union artillery. More worrisome to the regimental commander Colonel William Harman was the “large bodies of the enemy moving around” the right flank of his command. Luckily for the Virginian he did not have long to worry about this threat as he was ordered toward Sandy Ridge and eventually would come to occupy a position in the woodlot that crowned the crest of that prominence.[27]

Meanwhile, the 42nd Virginia, which had been supporting Ashby’s operations on the Confederate right had also been ordered over to the left flank of the Confederate force. Double-timing to reach their new assigned position, to the right of the 5th Virginia, the Southerners leant their muskets to the carnage unfolding in the afternoon. Along with two Confederate artillery pieces, the defense of Sandy Ridge, the defense was made with “a vigorous resistance to the advancing enemy.”[28]

This effort of the Virginians would provide cover for the two artillery pieces and the other units, running short of ammunition, to disengage. Garnett, managing the fighting of his brigade, began to receive worrisome news. Minus the 5th Virginia, which was detached, the rest of his command were all informing the 44-year old brigadier general that their ammunition was nearly exhausted. Deciding on the spot, Garnett realized that continued resistance without ammunition would serve no purpose and he gave the fateful order to retire. Along with the “Stonewall Brigade” the 21st and 27th Virginia also started to fall back.[29]

Meanwhile, Jackson, who was overseeing the action in a different sector of the battlefield, had no inkling that his subordinate had ordered over a third of his infantry force to retire from the field. He directed his horse into the retreating formations, asking soldiers why they were retreating. After receiving the answer of no ammunition, Jackson fired back with a fiery and determined response; “then go back and give them the bayonet.”[30]

Jackson even waylaid a drummer boy and instructed him to “Beat the rally.” Even this proved ineffectual to stem the tide of retreating Confederate soldiers. With Confederate infantry leaving the field of battle, Fulkerson’s own right flank was left unprotected. The unfolding battle had shifted the Virginians into a due north orientation since the start of the engagement upon their march toward Sandy Ridge. The two regiments on hand which had witnessed much of the engagement that day, also vacated their battle positions.[31]

With the retreat, which carried the foot soldiers down a slope to a local pond, a few of the Confederate infantry filed to the right and were able to escape the pursuing Union cavalry. The ones who took the left route headed right into the Federal horsemen and were captured.

As the Confederate forces departed back up the Valley Turnpike, Jackson finally came upon Garnett and asked him about the retreat. The Confederate commander insisted that reinforcements to his subordinate’s sector were on the way and that, although ammunition was depleted, the soldiers still carried the bayonet.

The decision to retreat would have future ramifications, for both Garnett and Jackson, which would not be settled by the time of the latter’s death in May 1863.

Out of the approximately 8,500 Union soldiers engaged on March 23, 1862 approximately 600 were listed as casualties. On the opposite side, Jackson had slightly over 3,500 men and over 700 men fell dead, wounded, or were missing because of the action. At the conclusion of the fighting the Union held the field and in terms of 19th century warfare, could claim victory.[32]

However, that was certainly not the lasting consequence of the brisk, yet, bitter battle that raged south of Winchester, Virginia on that Sabbath Day. The ripple effects would be felt in both capitals, Washington D.C. and Richmond, Virginia. Furthermore, Jackson’s appearance at Kernstown prompted a major reversal in Union strategic plans for the ensuing months.

Four days before the battle, Confederate General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, sent a missive to Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley on what his mission was, which directly led to the fighting at Kernstown. Having received word that Jackson had retreated up the Valley, the overall Confederate commander in Virginia sent the following dispatch, in which he wrote,

“Would not your presence with your troops near Winchester, prevent the enemy from diminishing his force there? I think it certain that it would. It is important to keep that army in the valley--& that it should not reinforce McClellan. So try to prevent it by keeping as near as prudence will permit.”[33]

To an aggressive and spirited commander, in which Jackson surely was, this directive led to his forward movement that culminated with the fighting on March 23rd. Although Johnston and Jackson both differed on how they viewed the war and what offensive maneuvers the Confederates in Virginia should resemble, both agreed that Jackson’s mere presence in the lower Shenandoah Valley could influence decisions in Washington D.C. Both were correct in that line of thinking.

For the Federals, the days after the battle saw constant motion. Bringing in the wounded, shepherding Confederate prisoners-of-war, and reminiscing of the ordeal they just passed through consumed most of soldiers’ time. Officers began preparations to decide the next step in strategy and started to wonder what Jackson’s reasoning for offering battle was. Did it mean that Jackson had more troops than initially thought?

With all this activity keeping most of the blue-coated soldiery busy, David Hunter Strother, illustrator and writer, whose work would later appear in Harper’s Weekly, ventured out to Sandy Ridge. Arriving on the Monday immediately following the battle, he recorded the following first-hand account of the scene that greeted his eyes.

“The fences were torn down and the ground marked with artillery wheels…a dead horse or two were visible and the body of a soldier with the top of his head blown of lay protected by a rail pen. Crossing a field and a wood I came upon an open ridge…and another body of a United States soldier lay. Near here a picket guard lay by the fire and beside them upon a rail trestle lay fifteen dead Federalists.”[34]

Strother even sallied over to the Confederate lines, where “within a very small space” he came upon “forty bodies of the Confederates.” Upon closer inspection “the bodies lay among the bushes and the trees just as they fell and were without exception shot through the head with musket balls.”[35]

Meanwhile, Shields and his superior officer, General Nathaniel Banks began to consolidate Union forces back in the environs of Winchester. One dispatch went to General Alpheus Williams’ Division to backtrack from Berryville, situated to the east of Winchester, accessible by the Leesburg Turnpike. Two of the three brigades, under Colonels Dudley Donnelly and George Gordon would arrive back to join Shields and Banks. The other, under Brigadier General John Joseph Abercrombie continued onto Manassas and eventually to McClellan’s forces on the Tidewater peninsula of Virginia; the only infantry force to leave the Valley and make it to the Union Army of the Potomac.[36]

With Union forces congregating back in the Valley and Jackson earning plaudits from the Confederate Congress, the Battle of Kernstown (or as the Union would initially call it, the Battle of Winchester) faded into the historical memory. The bloodletting, which initially horrified troops—both North and South—would mark the beginning of one of the most remarkable campaigns in the Civil War.

Jackson had set the table for what would unfold as his most daring and successful led campaign of his entire career. The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862.

- [1] Gary L. Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”: The First Battle of Kernstown (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1997), 40.

- [2] Lowell Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign: The Battle of Kernstown (Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, 1996), 50.

- [3] Ibid., 72.

- [4] Ibid., 72-73.

- [5]

- [6] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 70-71.

- [7] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 58-59.

- [8] Ibid., 83.

- [9] Ibid., 98.

- [10] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 75.

- [11] Ibid., 76.

- [12] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 105.

- [13] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 76; Peter Cozzens, Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 170.

- [14] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 76; Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 102.

- [15] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 77; Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 98.

- [16] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 77.

- [17] Ibid.

- [18] Ibid., 78.

- [19] Ibid., 79.

- [20] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 149; Cozzens, Shenandoah, 181.

- [21] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 138.

- [22] Ibid., 140.

- [23] Ibid.

- [24] Ibid., 144.

- [25] Ibid., 152-3.

- [26] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 80.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] William Allen, History of the Campaign of Gen. T. J. (Stonewall) Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, From November 4, 1861 to June 17, 1862 (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippinscott & CO, 1880), 52.

- [29] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 176-7.

- [30] Douglas Southall Freeman and Stephen W. Sears, Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command, Scribner 1998 ed. (New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1942-1944), 163.

- [31] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!” 185.

- [32] National Park Service, Soldiers and Sailors Database / Battles, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battles-detail.htm?battleCode=VA101, accessed May 22, 2021.

- [33] Ecelbarger, “We are in for it!”, 64.

- [34] Ibid., 210.

- [35] Cecil B. Eby, Jr., A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War: The Diaries of David Hunter Strother (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 19.

- [36] Reidenbaugh, Jackson’s Valley Campaign, 93.

If you can read only one book:

Ecelbarger, Gary L. “We are in for it!”: The First Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing, 1997.

Books:

Colt, Margaretta Barton. Defend the Valley: A Shenandoah Valley in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Dowdey, Clifford. "In the Valley of Virginia," in Civil War History 3: no.4 (December 1957): 401-22.

Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Noyalas, Jonathan A. Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign: War Comes to the Homefront. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

Robertson, Jr., James I. "Stonewall in the Shenandoah: The Valley Campaign of 1862," in Civil War Times Illustrated 11, no. 2 (February 1972): 4-49.

Tanner, Robert G. Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Doubleday, 1976.

Weber, Lawrence. "Stonewall's Victorious Defeat," in Military Heritage 13, no.4 (Winter 2012): 46-51.

Organizations:

Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District

In 1996, Congress designated eight counties in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia as a National Battlefield Site – the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District – which preserves and interprets the region’s significant Civil War battlefields and related historic sites. It is managed by the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation.

The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation

The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation manages the preservation of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District.

Contact: 9386 S Congress St., New Market, VA 22844 | 540-740-4545.

The Kernstown Battlefield Association

In 1996, the Kernstown Battlefield Association was formed as a 501(c)3 non-profit corporation whose mission was to acquire, preserve and interpret the Pritchard-Grim Farm as an historic resource.

Contact:

Kernstown Battlefield Association

PO Box 1327 Winchester, VA 22604

540 450 7835

Pritchard-Grim Farm

3050 Saratoga Drive Winchester, VA 22601

Kernstown Battlefield

610 Battle Park Drive, Winchester, VA 22601

Web Resources:

No web resources listed.

Other Sources:

Museum of the Shenandoah Valley

The Museum of the Shenandoah Valley houses a permanent collection of over 11,000 pieces including objects and artifacts of the Shenandoah Valley accumulated by the museum starting in 1999.

Contact: 901 Amherst Street Winchester, VA 22601, 888-556-5799.